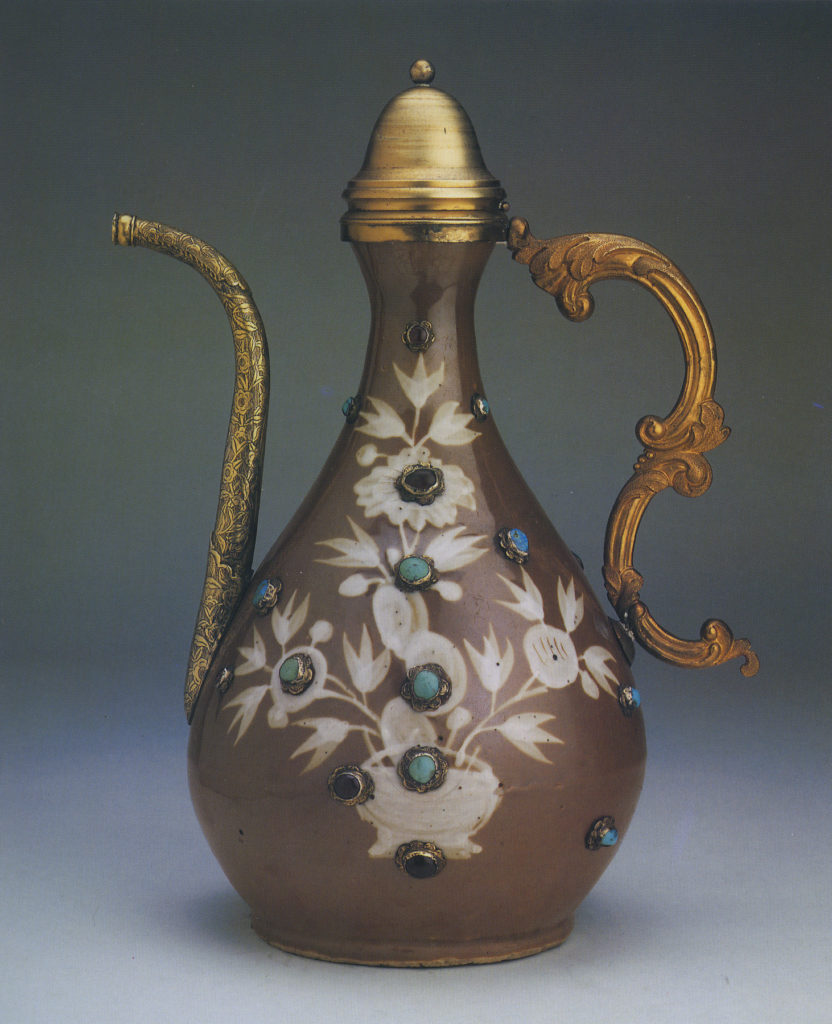

A Chinese porcelain ewer decorated in cobalt pigment under a clear glaze (underglaze blue), partially ornamented with cold applied gilding, and set with jeweled mounts of gilded silver was acquired by the Walters family prior to 1896 (fig. 1). In 2014–15, the ewer was the subject of technical study and conservation treatment in the Walters Art Museum’s Department of Conservation and Technical Research. This brought to light details about its materials and techniques of construction that indicated the jeweled mounts were the product of Ottoman imperial workshops of the sixteenth or seventeenth century, a fact that had not been noted previously. With this new information, the ewer was recognized as an extraordinarily rare survival of elite Ottoman imperial craftsmanship and included in the exhibition Pearls on a String: Artists, Patrons, and Poets at the Great Islamic Courts (2015–16).[1] Further study suggests the Walters ewer may be among the best-preserved examples of only seven extant Chinese porcelain vessels with a distinctive type of Ottoman jeweled mounts.

The ewer’s form and color, along with an inscription on the underside of its foot, dates it to the Wanli era (1572–1620) of the Ming dynasty (fig. 2).[2] The ewer was most likely manufactured in Jingdezhen, a major center of porcelain production at the time.[3] The form is derived from metal ewers used throughout the Islamic world, and it was probably designed specifically for export to the Persian or Ottoman markets.[4] Prior to the 2015 exhibition, the ewer had been catalogued, published, and exhibited solely as a Chinese porcelain, with only incidental consideration of the mounts. When considered at all, the jeweled mounts were described variously and inaccurately as “Persian,” “Indian,” or “Oriental.”[5] Further research by this author, together with close technical examination of the object, confirms the distinctly Ottoman character of these jeweled mounts and identifies six other closely related objects known today.[6]

Underside of the foot, showing Wan-li mark in underglaze blue. Note the large firing crack.

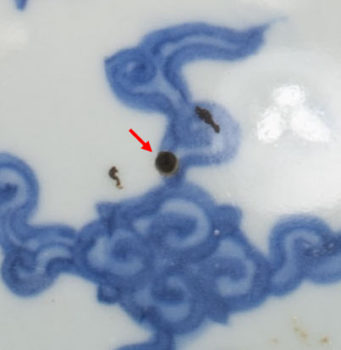

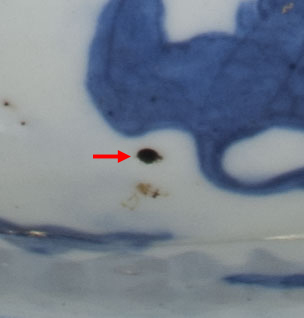

Chinese potters, probably at the kilns of Jingdezhen, assembled the ewer from six separately formed sections of porcelain. After an initial firing, the ewer was painted in underglaze blue with scenes of phoenixes among tufts of cloud. The separate porcelain sections are still recognizable as they did not completely fuse during firing, resulting in a series of cracks that formed at all of the joins; a large firing crack is also on the underside of the foot (fig. 2). The most prominent of these firing cracks, at the juncture between the ewer’s neck and body, was later repaired with six gilded copper alloy staples. [7]

The top of the handle retains evidence of the porcelain loop that would have secured the lid with a chain. This loop was broken or removed sometime before the jewels were added (one jewel now partially obscures the loop’s remains).[8] The hexagonal porcelain lid—partly covered by the gilded silver mount—is a poor fit to the circular rim of the ewer and has no corresponding loop for a chain, which tentatively suggests it may have been appropriated from another Chinese object.

At some point, the ewer was transported through networks of trade or by exchange from China to Constantinople. There, it was refashioned in the imperial workshop by artisans in the employ of the Ottoman court. Artisans specifically responsible for work in gold and precious metals added gilded silver mounts to the porcelain body and lid.[9] The foot of the ewer was fitted with a band of gilded silver, chased (chiseled with a sharp tool) with repeating flowers and leaves set against a background of vertical lines. In effect, this band hid the firing crack and other flaws on the foot and added approximately one centimeter in height. In addition to the mechanical joint formed by crimping (bending or burnishing the metal against the porcelain surface), a large quantity of a black resinous material was applied as an adhesive bond between the foot and the added band.[10] The end of the spout and the rims of the ewer and lid were fitted with similar gilded silver mounts attached in the same manner. In addition, Ottoman court artisans applied cold gilding, which survives only in small traces, appearing as small specks of gold on the surface of the porcelain.[11]

The most sumptuous aspect of the Walters ewer are the gemstones in gilded silver settings studding the body, handle, and spout. The ewer displays twenty-two turquoises, one ruby or spinel, seventeen garnets, and two emeralds or beryls. Three stones are missing. Following the established pattern, these were probably one turquoise, one red stone, and one green stone, bringing the original total of jewels to forty-five. The jewels were added by specialized court jewelers responsible for cutting and setting stones, possibly working alongside the goldsmiths or metalworkers.[12] These jewelers shaped and polished most of the stones in the manner of a cabochon cut, though several are faceted, and then fitted them all in petal-shaped bezel settings of multiple sizes with various types of chased decoration.

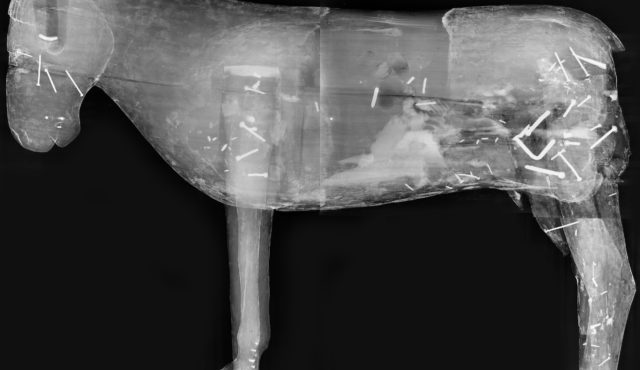

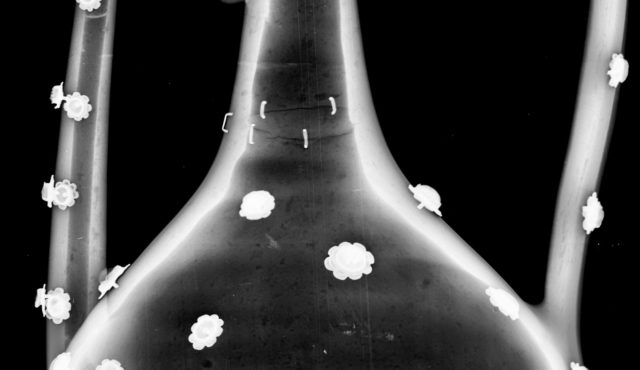

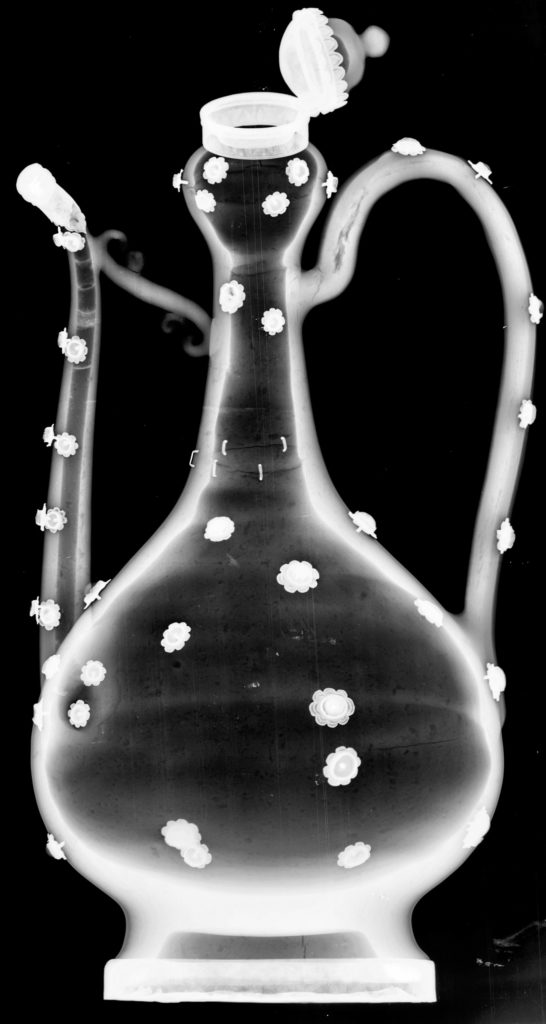

Court artisans attached the bezel-set gems to the body of the porcelain ewer by inserting short posts into small circular holes drilled partway through the walls of the vessel. They also adhered the settings with an abundance of the same dark resinous material found beneath the crimped band at the ewer’s foot.[13] Where the settings have been lost, the shallow drilled holes are easily observed (fig. 3). X-radiographs of the object clearly display the posts of intact settings, appearing as short cylindrical projections with irregularly cut ends (fig. 4). None of the drilled holes appear to extend through to the interior, ensuring that the ewer remains a functional vessel.

X-ray radiograph (120 kV, 1.0 μA, 60 sec.). Note the short projecting posts securing the bezels to the porcelain body.

The method of setting gems in bezels of this specific type onto porcelain, along with the mounts of gilded silver, is indicative of Ottoman court craftsmanship between the mid-sixteenth and mid-seventeenth century. Artisans working at the behest of the sultans exclusively performed this difficult, precise, and time-consuming labor of mounting Chinese porcelain with gemstones and precious metals.[14] Destined for the personal use of the highest-ranking members of the imperial court, jeweled porcelain items seem to have been produced in limited numbers.[15] The treasury register of AH 1091/1680 CE notes that only 371 out of a total of 4,534 porcelains were mounted with jewels.[16] As the practice of jeweling porcelain likely ceased around this time or shortly before, this number may be near the sum total of porcelains with jeweled mounts ever produced by Ottoman imperial workshops.[17] Today, Istanbul’s Topkapı Saray Museum holds 10,358 Chinese porcelains from the former Ottoman imperial collection, 273 of which have jeweled mounts; only a handful of jeweled porcelains are known to exist elsewhere.[18] The majority of the jeweled items at Topkapı are plates, dishes, and cups. Only eleven examples of other forms are known, making the Walters ewer especially unusual.[19]

On nearly all of these objects, Ottoman court artisans set the jewels in gold bezels into shallow ring- or disk-shaped grooves on the surface of the porcelain, often at the interstices of interlacing lines of inlaid gold (fig. 5). In technique and overall appearance, this type of jeweling resembles the older and more prevalent Ottoman practice of setting the surface of ornamental jade (or nephrite) by inlaying gold and precious stones.[20]

Fig. 5

TKS 15/2805, late 16th- or early 17th-century Chinese porcelain cup decorated in underglaze blue. With a row of green jewels between two of red connected by trellis work of inlaid gold wire. The vast majority of Ottoman jeweled mounts added to Chinese porcelains are set into similar shallow rings or disks and are accompanied by inlaid lines of gold wire or foil. Illustrated in Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul: A Complete Catalogue, ed. John Ayers, vol. 2, Yuan and Ming Dynasty Porcelains (London: Directorate of the Topkapı Saray Museum in association with Sotheby’s Publications, 1986), 841, nos. 1739, 1738

TKS 15/2801, a similar late 16th-century Chinese porcelain cup decorated in underglaze blue formerly with three rows of jewels connected by inlaid trellis (the jewels and inlay now missing).

Somewhat surprisingly, only six jeweled porcelains at Topkapı share the distinctive gilded-silver jeweled mounts set into small drilled holes as on the Walters ewer; on all other known examples the jewels have been fitted in the more common type of settings—that is, within gold settings in shallow grooves. Of these six related drilled-hole jeweled porcelains, only one survives largely intact: a late sixteenth- or early seventeenth-century Chinese bottle mounted as a ewer set with seventeenth-century Ottoman gilded silver jeweled mounts (fig. 6). [21] The five other porcelains, comprising another bottle mounted as a ewer and four basins, have drilled holes for similar settings but do not retain all their jewels. [22] These six objects at Topkapı share a number of features with the Walters ewer beyond the drilled settings of their jewels, including gilt silver mounts, a lack of additional inlaid gold lines commonly found among other examples, and a preponderance of turquoises where the jeweling survives. In addition, traces of cold gilding survive on the exteriors of four of the six.[23] Out of the total group of seven objects, the Walters ewer is the most elaborate Chinese porcelain form, with the best preserved Ottoman jewels and mounts.

TKS 15/2769, late16th- or early 17th-century Chinese porcelain bottle set with jewels in 17th-century gilt silver Ottoman mounts. The handle and lid are 19th-century additions. Note the small drilled holes where bezel settings have been lost. This method of securing Ottoman jeweled mounts to Chinese porcelains is known on only seven objects, of which the Walters ewer is the best preserved. Illustrated in Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul: A Complete Catalogue, ed. John Ayers, vol. 2, Yuan and Ming Dynasty Porcelains (London: Directorate of the Topkapı Saray Museum in association with Sotheby’s Publications, 1986), 479, no. 1903

Interestingly, this group of seven known closely related jeweled porcelains in drilled settings consists entirely of ewers and basins, in nearly equal numbers of each. While there is no direct evidence that this group was intended as a unified suite, apart from their shared materials and techniques of embellishment, it is worth noting that they are all items for washing and ablution, a hygienic and religious task afforded great importance in the Ottoman court.[24]

Given the closely related techniques of embellishment shared by this group, the traces of applied cold gilding on the Walters ewer assume new technical importance, as this gilding is a distinctive feature of a majority of the items in the group, but otherwise unknown among other surviving examples of jeweled porcelain. Due to the fragmentary nature of the gilding, it is not possible to reconstruct the original design on the Walters ewer, though it surely would have added to the spectacular appearance of the object when newly applied.[25] The gilded staples securing the firing crack on the neck also assume new importance when considered in relation to this group. The technique of repairing ceramics with metal staples shares much in common with the approach to mounting the jewels on this ewer and the related objects, in that both techniques rely on precisely drilling partway through the ceramic wall to insert short wires or posts. The presence of gilding on the staples is unusually decorative for a functional repair, but in keeping with the aesthetics of the applied gilding and the occasional ornamental metal repairs found on other Chinese porcelains from the Ottoman imperial collections.[26] It is therefore likely that the staples were added at the same time as the mounts to ensure that the ewer would remain functional without risk of leaks or separation at the crack.

The materials and methods of manufacture employed for the jeweling and mounting of this Chinese porcelain ewer confirm that it was transformed by the workshops of the Ottoman imperial court. Most jeweled sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Chinese porcelain in Topkapı Saray is believed to have been embellished shortly after its export; thus it is likely that the jeweled mounts on the Walters ewer date to the late sixteenth or early to mid-seventeenth century as well.[27] The existence of only six other closely related items makes the Walters ewer an extremely important survival of this type of elite Ottoman imperial craftsmanship.

It is unclear how and when the Walters ewer left the imperial treasury, though a number of possibilities may be considered. Only a small number of jeweled porcelains from the Ottoman imperial collections are known to have been sold; indeed, during the most significant period of these sales in the eighteenth century, when 2,669 porcelains were sold, only four were recorded as jeweled items.[28] Viziers and other high-ranking officials occasionally received gifts of porcelains, some of which may have been jeweled.[29] Jeweled porcelains also formed an important part of the dowries of imperial princesses, though these customarily reverted to the treasury upon their deaths.[30] Porcelains were occasionally bestowed as diplomatic gifts, though no firm documentation exists to suggest that these included jeweled porcelains.[31] Porcelains might also be given as personal gifts from the sultan, such as the two bowls given to the British Ambassador Sir Austen Henry Layard and his wife, Lady Layard, Mary Enid Evelyn Guest, in AH 1296/1877 CE, at least one of which was set with jewels.[32]

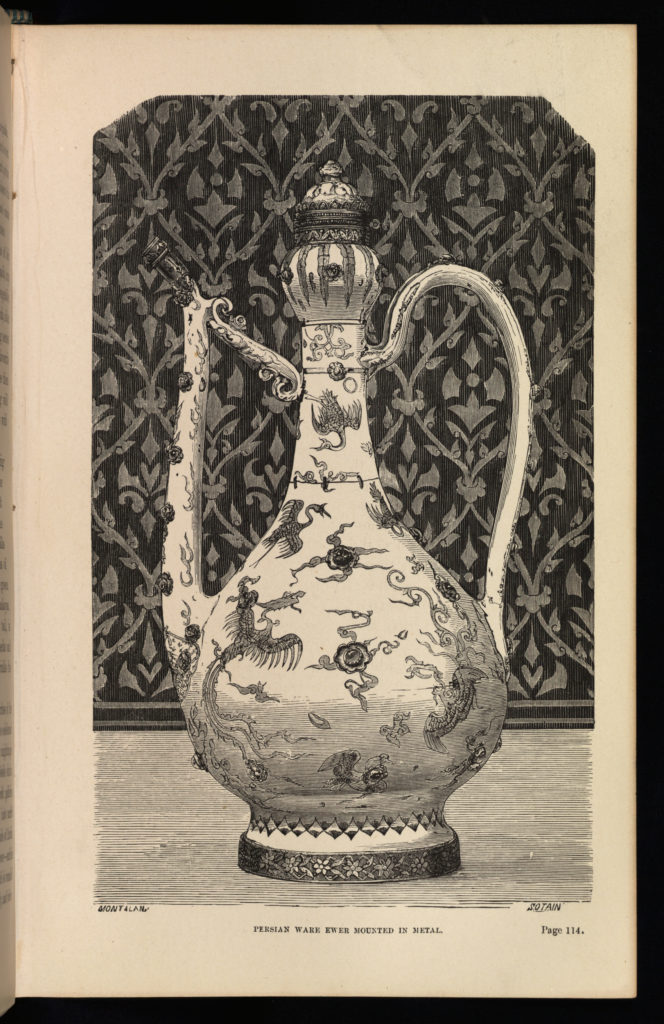

Engraving of the porcelain ewer from Philippe Burty, Chefs d’Oeuvre of the Industrial Arts, 1869.

Whether by sale or by gift, the Walters ewer had made its way to Europe by 1866, when it appeared as an illustration in the book Chefs-d’Oeuvre des arts industriels by Philippe Burty (fig. 7).[33] The Walters ewer, recognizable by its distinctive staple repairs, appears in a full-page illustration (signed below image: Montalan [at left]; Sotain[34] [at right]) with the rather ambiguous caption “Persian ware ewer mounted in metal.”[35] Though the ewer is not discussed specifically in the text, it is situated in the midst of a disquisition on the nature of Persian ceramics, which would make it seem that Burty was under the impression that the ewer was of Persian origin. No information is provided on the provenance of the ewer, and its location and ownership at the time of Burty’s publication remain unclear.[36] Elsewhere within the text, Burty mentions “oriental” ceramics at the 1867 Union Centrale international exposition in Paris; it is possible that the ewer was exhibited there but this remains unproven.[37]

Compounding the apparent confusion as to the origin of the ewer, William T. Walters in his 1884 publication Oriental Collection of W. T. Walters referred to a collection of Chinese porcelains with “Persian” mounts at the 1873 Vienna international exposition, some of which he acquired: “Not the least interesting incident in our experience there was encountering the collection of Chinese porcelain, owned and sent by Prince Ehtezadesaltanet [E’tezad es-Saltaneh], uncle of the Shah of Persia [Naser Al-Din Shah Qajar]. The collection contained many rare and desirable objects, all bearing date[s] previous to 1630…. Our collection contains a number of the choicest selections from this remarkable exhibit, a part of them with intricate and characteristic Persian mounts in metal.”[38]

It remains unclear whether the Walters ewer was in fact part of this collection, but the vague description of the prince’s porcelains and their mounts could easily be interpreted as a reference to the ewer.

Perhaps based on this equivocal evidence, Stephen W. Bushell in Oriental Ceramic Art: Collection of W. T. Walters (1896) describes the Walters porcelain as “a tall ewer of graceful form decorated in the style and coloring of the Wan-li period, with blue phoenixes and storks flying among clouds. It is studded all over with uncut turquoises and garnets arranged alternately, mounted in gilded settings of Persian or Indian workmanship, shows traces of gilded rings, and is fitted at the upper and lower rims and at the end of the spout with engraved metal mounts.”[39]

Although it is not known why uncertainty about the ewer’s origin might have arisen, more confusion seems to have been initiated by Burty’s misattribution of the porcelain as Persian. This inaccuracy may be ascribed to a generally vague notion of “the Orient” in nineteenth-century scholarship; however, it is worth considering whether it contains a kernel of truth. Gifts from foreign powers were among the most important sources of Chinese porcelains entering the Ottoman imperial treasury during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These include gifts from the Safavid shahs of Persia documented on at least seven occasions between AH 963 and 1108/1555 and 1697 CE.[40] There is also some evidence that the Ottoman emperor Süleyman the Magnificent (reigned 1520–1566) received a large gift of Chinese porcelains from India.[41] Finally, while it is possible that after the ewer was jeweled and embellished it was later given to the Shah or another member of the Persian court, no record of such a gift exists.[42]

Thus, while the complicated history of exchange that transported and transformed the ewer across space and time from the kilns of Jingdezhen to the Walters Art Museum may remain shrouded in mystery, the current study of its technical aspects has helped to reestablish it as an important and well-preserved example of Ottoman imperial court art of an extremely rare type.

Sincere thanks to Amy Landau, formerly Walters Art Museum’s Director of Curatorial Affairs and Curator of Islamic & South Asian Art, whose interest in this object spurred the research presented in this paper. Many thanks as well to Dany Chan, Associate Curator of Asian Art, and Ashley Dimmig, Wieler-Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow, at the Walters Art Museum, as well as other readers of this paper for their thoughtful comments.

[1] The exhibition was organized by the Walters Art Museum (November 8, 2015–January 31, 2016), in partnership with the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco (February 26–May 8, 2016).

[2] S. W. Bushell, Oriental Ceramic Art: Collection of W. T. Walters. (New York, 1896; New York: Crown Publishers, 1980), 54. Page references are to the 1980 edition.

[3] Richard H. Randall Jr., “Masterpieces of Chinese Porcelains,” The Walters Art Gallery Bulletin 33, no. 1 (October 1980): 4.

[4]Julian Raby and Ünsal Yücel, “Blue-and-White, Celadon and Whitewares: Iznik’s Debt to China,” Oriental Art 29, no. 1 (1983): 38.

[5] Bushell, Oriental Ceramic Art, 54, 834; Philippe Burty, Chefs-d’Oeuvre of the Industrial Arts, ed. William Chaffers (London, 1869), 114.

[6] The other six are all preserved in the collections of Topkapı Saray Museum: inv. nos. TKS 15/199; TKS 15/2028; TKS 15/2163; TKS 15/2793; TKS 15/2514.

[7] Staple repairs to ceramics, common in the ancient until recent past, insert bent metal wires into shallow holes drilled on either side of a crack or break, which is then held together by the inward tension of the bent staples.

[8] Intact loops of this sort are present on other Chinese porcelain ewers made for the Middle Eastern market. An example of nearly identical form with a Persian silver lid (no chain present) is in the Victoria and Albert Museum (inv. no. C.222-1931). See also Lot 348 of Sotheby’s Arts of the Islamic World Sale, London, October 5, 2011, for a related form with Ottoman tombac lid and chain.

[9] Regina Krahl, “Porcelain with Ottoman Jewelled Decoration,” in Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul: A Complete Catalogue, ed. John Ayers, vol. 2, Yuan and Ming Dynasty Porcelains (London: Directorate of the Topkapı Saray Museum in association with Sotheby’s Publications, 1986), 833.

[10] This material has not been analyzed; however, it exhibits no visible fluorescence under ultraviolet radiation, suggesting it may be bituminous rather than a plant resin.

[11] Cold gilding of ceramics or glass is a process of applying an adhesive (size or glue) to the surface, then gold leaf is placed on top of the size once it has dried until tacky. If a small amount of bole is added to the size, the gilding may be burnished, making it appear brighter and glossier.

[12] Krahl, “Porcelain with Ottoman Jewelled Decoration,” 833. Some of the most important court jewelers of the seventeenth century (and later) were members of the Christian Armenian Düz family. For a discussion of the family’s involvement in the creation of eighteenth-century items for the Ottoman imperial court, see Bora Keskiner, Ünver Rüstem, and Tim Stanley, “Armed and Splendorous: The Jeweled Gun of Mahmud I,” in Pearls on a String: Artists, Patrons, and Poets of the Great Islamic Courts, ed. Amy S. Landau (Baltimore: The Walters Art Museum in association with the University of Washington Press), 219‒20.

[13] The liberal use of adhesive may be one reason that so much of the jeweling survives intact.

[14] Krahl, 833.

[15] There is evidence to suggest that jeweled porcelains were not merely display objects but were indeed used for eating, drinking, and washing. Julian Raby and Ünsal Yücel, “Chinese Porcelain at the Ottoman Court,” in Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul: A Complete Catalogue, ed. John Ayers, vol. 1, Yuan and Ming Dynasty Celadon Wares (London: Directorate of the Topkapı Saray Museum in association with Sotheby’s Publications, 1986), 49.

[17] Jeweled porcelains were most frequently recorded in separate, detailed sections of imperial treasury inventories. The AH 920/1514 CE inventory records no jeweled porcelains, while the partial inventory of AH 941‒942/1534‒36 CE (which records only jeweled porcelains) notes four, evidence that the practice of setting porcelains with jewels initiated sometime between these dates. The inventory of AH 1091/1680 CE records the highest number of jeweled porcelains (371). Subsequent inventories of AH 1127/1715 CE, AH 1174/1760 CE, and thereafter record static or declining numbers. For a detailed discussion of these inventories, see Julian Raby and Ünsal Yücel, “The Archival Documentation: The Scope of the Documents,” in Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul: A Complete Catalogue, ed. John Ayers, vol. 1, Yuan and Ming Dynasty Celadon Wares (London: Directorate of the Topkapı Saray Museum in association with Sotheby’s Publications, 1986), 65‒76. This documentary evidence, together with a stylistic analysis of both the porcelain and the jeweled decoration, indicates the production of jeweled porcelains likely ceased sometime near the middle of the seventeenth century. Raby and Yücel, “Chinese Porcelain at the Ottoman Court,” 48; Krahl, “Porcelain with Ottoman Jewelled Decoration,” 833.

[18] Raby and Yücel, 48.

[19] Raby and Yücel, 48. Two bottles, two kendi, four composite incense burners, one box, one pen box, and one cover.

[20] For an example of ornamental nephrite plaques set with gold and other precious stones incorporated into an imperial Ottoman object, see the jeweled gun of Sultan Mahmud I, dated AH 1145/1732‒33 CE, (Walters Art Museum, acc. no. 51.84). The gun is discussed at length in Bora Keskiner, Ünver Rüstem, and Tim Stanley, “Armed and Splendorous: The Jeweled Gun of Mahmud I,” in Pearls on a String: Artists, Patrons, and Poets of the Great Islamic Courts, ed. Amy S. Landau (Baltimore: The Walters Art Museum in association with the University of Washington Press), 205‒41.

[21] Krahl and Nurdan Erbahar, Chinese Ceramics, vol. 2, Yuan and Ming Dynasty Porcelains, cat. 1903, 880–81. The handle and lid are nineteenth-century additions or replacements.

[22] Krahl, “Porcelain with Ottoman Jewelled Decoration,” 834.

[23] Krahl and Erbahar, cats. 223, 790, 875, 1482, 1485. [TKS 15/199 celadon bottle (ca. 1400) mounted as a ewer with Ottoman gilded silver handle and foot. A hole remains where the spout was previously attached, as well as tiny drilled holes where once studded with jewels; TKS 15/2028 blue-and-white dish (early sixteenth century) with foliate and floral gilding, set with a gilded silver Ottoman mount to the rim and ten jewels in drilled holes, of which a single turquoise remains; TKS 15/2163 a blue-and-white basin (second quarter of the sixteenth century) with gilded floral motif, Solomon’s seal emblems, and other designs, and drilled holes from jeweling, also with an Ottoman rim mount of gilded silver; TKS 15/2793 a blue-and-white basin (late sixteenth/early seventeenth century) with traces of gilded floral decoration, turquoise studs, and an Ottoman gilded silver mount to the rim; 1485 TKS 15/2514 blue-and-white basin (early seventeenth century) with traces of gilding and drilled holes from jeweling.]

[24] Raby and Yücel, “Chinese Porcelain,” 42.

[25] The technique has never been very durable, and Robert Dossie in Handmaid to the Arts (London, 1758) noted that “the gold peels and rubs off in spots, and renders it very unsightly” (400).

[26] Raby and Yücel, “Chinese Porcelain,” 49–50.

[27] Krahl, “Porcelain with Ottoman Jewelled Decoration,” 833

[28] Raby and Yücel, 37

[29] Raby and Yücel, 48. Two possible gifts are such examples now in the National Museum at Krakow (Czartoryski collection, inv. no. XIII-1682 ab). By tradition, they are said to have been seized from Kara Mustafa Paşa at the siege of Vienna in AH 1093/1683 CE.

[30] Raby and Yücel, 47; Tulay Artan, “Eighteenth-Century Ottoman Princesses as Collectors: Chinese and European Porcelains in the Topkapı Palace Museum,” in “Globalizing Cultures: Art and Mobility in the Eighteenth Century,” special issue, Ars Orientalis 39, (2010): 113.

[31]Raby and Yücel, “Chinese Porcelain,” 36.

[32] Raby and Yücel, 37. The bowl, of porcelain from the Jingdezhen kilns, is set with rubies in gold settings with gold interlace. It is currently in the British Museum (inv. no. 1904,0714.1).

[33] Philippe Burty, Chefs-d’oeuvre des arts industriels: ceramique, vererrie, vitraux, emaux, metaux, orféverie & bijouterie, tapisserie (Paris: Ducrocq, 1866), 179. Portions of this book were later republished in an English translation in 1869 as Chefs-d’Oeuvre of the Industrial Arts, where the same engraving appears on page 114.

[34] Possibly the engraver Noël Eugène Sotain, active after ca. 1816.

[35] In the original French: “Aiguière montée en orféverie. Faïence de Perse.” Burty, Chefs-d’Oeuvre, 1866, 179.

[36] Given the lack of attribution, it is possible that the ewer may have been among Burty’s personal collection. Alternatively, the engraving of the ewer may have been republished from an earlier arts publication such as the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, to which Burty was a frequent contributor. I am grateful to Jo Briggs, Jennie Walters Delano Curator of 18th- and 19th-Century Art, for this astute observation.

[37] Burty, Chefs-d’Oeuvre, 1869, 112.

[38] [William T. Walters], Oriental Collection of W. T. Walters, 65 Mount Vernon Place (Baltimore, 1884), ix. Chinese porcelain ewers with documented Persian metal mounts are known; of particular interest is an example in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum (C.222-1931). The V&A ewer, made in Jingdezhen (ca. 1522–66), is nearly identical in form to the Walters ewer. Curiously, the V&A ewer bears the coat of arms of a Portuguese trader, Antonio Peixoto, who is known to have traveled to China in the 1540s, stopping in Persia on the return journey. The mounts, made in Persia at that time, are of silver, with engraved floral patterns in a geometric repeat, possibly with niello added to the reserves (see V&A records for inv. no. C.222-1931). No jewels are added to the porcelain, and the materials and techniques of manufacture employed on these mounts (to say nothing of style) are not closely related to Ottoman metal mounts added to Chinese porcelain during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

[39] Bushell, Oriental Ceramic Art, 96.

[40] Raby and Yücel, 30.

[41] Raby and Yücel, 31.

[42] Conversely, the only recorded instance of the Ottoman Imperial court gifting porcelain to a member of the Persian court is a gift to Prince Safi in AH 1156/1743–44 CE of 134 porcelain items, none of which are noted as jeweled. Raby and Yücel, 36‒37.