Two Thai paintings at the Walters Art Museum diverge from the devotional themes that dominate the museum’s Southeast Asian holdings.1 The style of the paintings recalls that favored by artists trained in European traditions, and both works depict historical events important to the construction of the modern nation of Siam, as Thailand was known until 1939.2 This brief study explores their subject matter, style, and connection to cultural and political developments (in particular, the Chakri Reformation) in late nineteenth-century Siam.3

The first of the two paintings (fig. 1) is a battle scene, with Siamese and Burmese officers and soldiers mounted on elephants while soldiers standing on the ground fire rifles. The composition is lively and energetic; the elephant at center right lifts its front feet off the ground in a display of attacking force. The high status of the men riding the elephants is signaled by the tiered white umbrellas, the peacock feathers, and ornate headgear. The man at the center of the painting wearing an elaborate helmet may be a prince or a general; the figure opposite him wearing a pointed black hat and seated under an umbrella with nine tiers is probably the highest ranking officer of his army. An imaginary representation of a battle from several centuries earlier, the painting, which dates from the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, incorporates historical aspects of the practice of warfare during the Ayutthaya period (1351–1767).4 Although few paintings or textiles survive from the period, the clothing worn at court and by soldiers was described by European visitors and in regional historical chronicles. Representations of Ayutthaya period clothing in nineteenth- and twentieth-century paintings, including those discussed here, are probably based on later clothing. The painter carefully depicted details of the soldiers’ uniforms, and he gave the men individualized expressions (fig. 2). The churning disorder of the scene favors neither side, but its Siamese origin suggests that the painting is intended to glorify Siamese power. The Burmese were enemies of the Siamese for centuries, and the two kingdoms

battled on many occasions. Because the scenes record Siamese victory over a Burmese army, the paintings are both narrative and symbolic, commemorating an important moment in Siamese history and emphasizing Siamese national identity: “Siamese-ness.”5

Battle Scene. Thailand, early 20th century. Paint on canvas, 36 × 42 15/16 in. (91.5 × 109 cm) with frame. The Walters Art Museum,

gift from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation’s Southeast Asian Art Collection, 2002, acc. no. 35.229

In contrast to the frenzied activity of the battle scene, the other painting (fig. 3) is a scene of relative calm. Two groups of soldiers face one another; a delegation from the army on the right kneels submissively, surrendering to the army on the left. Each army is led by a man on horseback, and both of the riders are accompanied by attendants holding red parasols. The man on the left wears the same black pointed hat as the general in the other painting, indicating that this is either the same officer or an individual of equal status. Formally, the landscape is rendered in a manner that suggests depth through linear perspective. The diminution of the trees and figures as they recede into the picture space defines an illusionistic context for the narrative. The soldiers’ dress emphasizes national differences between the two sides (fig. 4). Both paintings bear the same signature in the lower

right corner: ไทวิจารณ์ (Thai Wicharn; fig. 5). At least one other history painting in the National Museum of Thailand in Bangkok is similarly signed, suggesting that these compositions might constitute a series by a single artist.6 Without further documentation, however, it is not clear who the artist was. “Thai Wicharn” may be a pseudonym of a better-known artist active in the late nineteenth century or early twentieth century.

That the armies in both paintings are Siamese and Burmese can be inferred by examining the soldiers’ clothing. The Siamese soldiers wear red cotton shirts with apotropaic faces painted across their shoulders and striped chong kraben, a wrapped cloth, on the lower half of their bodies. One Siamese soldier is depicted tumbling on the ground, exposing his tattooed thighs. The higher-ranking officers wear brocaded jackets and elaborate black and gold helmets.7 On the opposing side, the Burmese troops wear checked or single-colored longyi, simple buttoned shirts, white cloths around their waists, and white cloth headgear typical of Burmese dress.

The combination of illustionistic space, linear perspective, and historical narrative makes these images a life-like record of a specific historical moment important to the identity of the Siamese nation. The Walters’ history paintings are grounded in the emerging nationalism of late nineteenth-century Siam. They reflect the shaping of a national identity

at a time when Bangkok was defining its boundaries and representing itself as an equal of European powers.

The two paintings are products of a particular historical moment. The colonial powers of Great Britain and France were threatening Siam’s borders, and rather than see his palace overtaken by European armies, as happened in Burma, King Rama V (also known as King Chlalongkorn [r. 1868–1910]) desired to be viewed by Europeans as an equal.8 One of the

ways to achieve this was by using a visual language associated with Europe. These paintings depict Siamese history but adopt a new style and approach to painting. Instead of the flat planes and idealized faces characteristic of classical Siamese painting, the artist uses linear perspective to create pictorial depth. A clear attempt has also been made to represent the participants as individuals. Finally, rather than religious narratives, these images present historical events recorded in written chronicles.

These paintings are part of a visual program developed in the late nineteenth century that asserted a national character at a time when the creation of a modern, unified nation was of great concern to Siam’s leaders. The paintings, and the larger agenda of which they were a part, highlight an aspect of Siamese identity that was particularly appealing to the royal family who were the patrons of works commemorating Siam’s history rendered in the European style. The employment of this new painting style together with a focus on historical events represents a larger overall shift in Siamese art and culture that continues to resonate today.

The 1887 History Paintings

History painting never reached the level of popularity in Siam that it did in nineteenth-century Europe, Japan, or China, but its importance should be considered in an understanding of modern Thai art. A significant moment in the development of history painting in Siam can be traced to Rama V in the year 1887. Rama V is well known for his efforts toward defining a national Siamese identity.9 He was interested in European art, culture, and civic ideas with a view to creating a modern state. These paintings speak to

that historical moment.

In 1887, Rama V held a painting competition that invited artists to produce paintings that chronicled Siamese history.10 Each painting was accompanied by a multistanza poem known as a khlong (โคลง).11 The poems were commissioned after the completion of the compositions and give insight into their subject matter. A total of ninety-two paintings resulted from this competition. The paintings are broad in their range of subjects and diverse in their stylistic approach. Many record episodes from the history of the Ayutthaya kingdom, alluding to the kingdom’s status as the foundation of Siamese identity. Some depict historical events from the early years of the urban centers of Thonburi and Bangkok, while others treat the Ayutthaya kingdom’s and the Rattanakosin (1782–present) kingdom’s relationships with their neighbors: Lanna, Laos, Burma, and Cambodia. Each offers a glimpse into the history that served to promote the formation of Rama V’s Bangkok-centered kingdom.

Once the 1887 competition ended, the series of ninety-two paintings was used to decorate the royal cremation grounds. The paintings were then hung in the throne hall at the Grand Palace in Bangkok and at Bang Pa-In, the summer palace near Ayutthaya. Sometime in the twentieth century, the paintings were distributed among a number of royal households, and several entered the collections of the National Museum and the National Gallery in Bangkok. Forty-one of the paintings have been located by the Thai Department of Fine Arts; the others remain unaccounted for.12

Many of the artists who contributed to the 1887 competition were members of the extended royal family. As elite members of Bangkok society, they had privileged access to resources not available to other artists, including art and objects from Europe and China. Among the artists participating in the 1887 competition, Prince Naris (1863–1947; full name: Naritsaranuwattiwong; in Thai: นริศรานุวัดติวงศ์), a cousin of Rama V, is perhaps the most famous. Prince Naris was a perceptive and compelling artist, writer, and architect. He designed Wat Benchamabophit, known as the Marble Temple, in Bangkok, as well as the city’s seal. He entered several works in the competition, winning first place with a painting entitled Phra Maha Uparacha Riding His Elephant to Attack King Phumintharacha’s Elephant.13 This dark and atmospheric painting, apparently set at dusk, depicts an Ayutthaya-period king surviving his brother’s attempt to

take control of the kingdom. It was one of several paintings displayed at the Bang Pa-In Palace after the competition ended.14

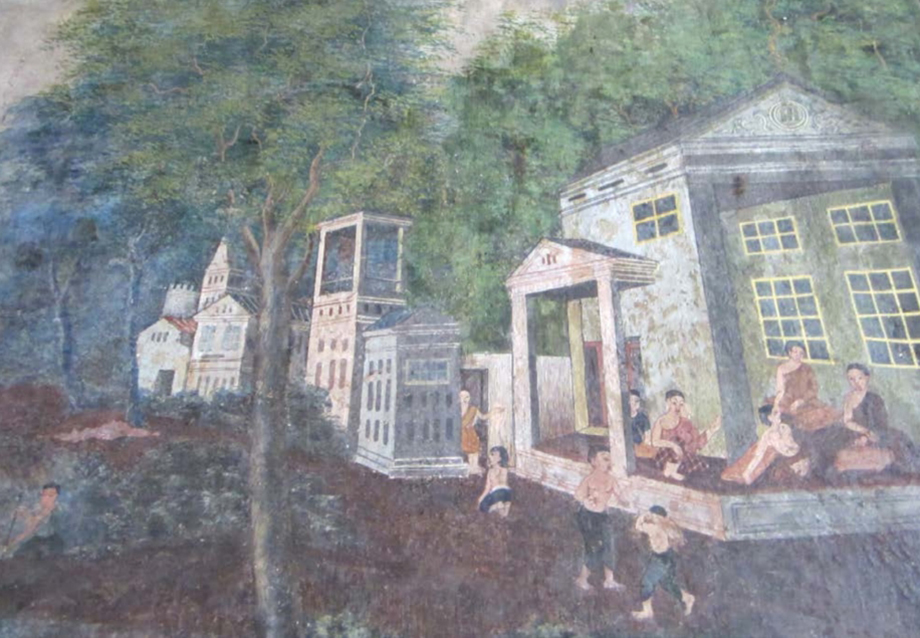

The stylistic and thematic departure of the 1887 chronicle paintings from traditional Siamese paintings of the period is significant, though changes in murals and paintings on cloth had already been underway. Thai painting typically used flat planes of color and undifferentiated figures to create an idealized space for depicting religious narratives.15 Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, painters incorporated historical references and European-style treatment of buildings, people, and landscapes into Siamese mural painting. King Mongkut, also known as King Rama IV (r. 1851–1868) and the father of Rama V, was a patron of the artist Khrua In Khong, a monk

active in the 1850s and 1860s whose Buddhist-themed wat (monastery) murals in Bangkok incorporated Western-style landscapes and perspectives.16 Although Khrua In Khong never traveled outside of Siam, he would have become familiar with European art through prints and photographs sent to Siam from abroad.17 Rama IV encouraged Khrua In Khong to experiment with European-style painting, and the artist

painted wall murals in several wats in Bangkok, of which the best known is Wat Bowoniwet (fig. 6). He incorporated historical subject matter into his murals, and his innovative approach informed later developments in Thai painting, including, in all likelihood, the 1887 series. Glass paintings

imported from China were another important source of inspiration for nineteenth-century Thai painting. These paintings, which typically used European artistic conventions of perspective, shading, and three-dimensionality, were popular in elites circles in Bangkok and can still be seen hanging in wats around Bangkok today.18

Detail of mural from Wat Bowoniwet, Bangkok, painted by Khrua In Khong, mid-19th century (Photo Rebecca S. Hall)

The tradition of recording civic and religious history, however, is rooted in the long, elaborate chronicles cherished by Siamese society. Chronicles were used by the Siamese to justify rulership, establish religious and royal lineage, and elevate history to mythic status; the tradition continues in the

present day. The Ayutthaya- and Bangkok-period chronicles, written before the mid-nineteenth century, were a point of departure for many of the paintings entered in the 1887 competition and the accompanying poems. These paintings are a continuation or even a new interpretation of the chronicle tradition. Thus, while these paintings are accurately characterized as “history paintings,” the Thai language–equivalent term ภาพพระราชพงศาวดาร (phap phraratchaphongsawadan) or “royal chronicle paintings” is more informative about the Siamese context and understanding of history.

Rama V’s commission of paintings depicting Siamese history was intended to validate or emphasize Siamese identity. Similar concerns inform contemporary Thai discourse and have recently emerged quite publicly, manifested in the regionalism that inspired the protests across Thailand in the twenty-first century, notably following a coup in September 2006, again in 2008, and continuing until the coup in May 2014.

Rama V and the Nation of Siam

Rama V is known as Siam’s great modernizer, building upon the policies begun by his father, King Mongkut. Facing European encroachment into his kingdom, Rama V looked to secure the borders that previously had been on the kingdom of Siam’s periphery, employing a variety of strategies to incorporate peoples on the fringes of his kingdom into a single nation. Laws regulating language and religious practice were one aspect of Rama V’s program to forge a national identity. The effects of these changes continue today in such policies as the mandatory teaching of the Central Thai language and the regulation of Buddhist texts and practices.

Test spotify audio

Scholars describe Rama V as a key player in maintaining Siam’s independence from Britain and France as neighboring countries in Southeast Asia were colonized; at the same time his intellectual interests in European culture cannot be disputed.19 His preference for European modes in state-sponsored architecture, for example, is demonstrated throughout Bangkok.20 He traveled to Europe many times during his reign, amassing a collection of European art that undoubtedly influenced the artists who contributed to the 1887 competition. Rama V sought to synthesize aspects of Siamese culture with European traditions. Court dress was Westernized, and new buildings used for government and palace affairs, including the Dusit throne hall, combined European and Siamese features.21 One strategy for creating and maintaining a national identity was to establish a unifying past that emphasized the king as the center of Siamese political and military power, but also one that could become accessible to all members of the nation. The 1887 paintings were part of that much larger cultural shift. The paintings commissioned by Rama V looked to Europe in form and execution, but the tradition of recording royal and religious history is deeply rooted in Siamese society. These paintings are the visual continuation of this textual tradition.

testing media area block

Royal portraits were a new phenomenon when Rama V took the throne, as the tradition of displaying images of the king in public spaces had only recently been adopted by his father. It functioned as another form of nationalism, because spaces that contained the king’s portrait were clearly

being marked as “Siamese.” This assertion of state authority continues today: portraits of the royal family are commonly hung in Thai homes, businesses, and on the street.

Scholars studying Rama V’s reign have proposed that one of the terms best used to understand the changes transpiring during that period is siwilai, a transliteration of the English adjective “civilized,” that refers both to manners and to etiquette. Siwilai applied principally to Bangkok’s elite, and the word reflected a desire to project the superiority of Siamese power and culture.22 As a word and a phenomenon, siwilai is a combination of the local and the foreign; a simultaneous display of Siamese expression and European influence. Siwilai was about civilization, but the term more specifically alluded to cultural strategies to ensure the survival of the Siamese nation. Indeed, it became a rallying cry for nationalism. One aspect of creating and maintaining that newfound sense of nation was the establishment of a unifying past—both a reminder that Siam’s civic and military power was concentrated in the king and an allusion to a past in which all members of the nation could take pride.

Rama V’s interest in the West found expression in a variety of visual projects that displayed siwilai throughout the capital. The king commissioned European architects to build government buildings and palaces, and he hired European artists to paint portraits of the royal family. Photography was another visual medium used by Rama V to project a modern image of the nation, and of the monarchy in particular. Scholars have recently explored Rama V’s artistic and architectural programs, relating them specifically to the goals of maintaining Siam’s independent status and elevating Siam as a modern nation.23 The 1887 history paintings were part of that artistic program. In other words, architecture, photography, portraits, and history paintings are each a visual manifestation of Rama V’s siwilai agenda. The king was adept at using the arts to support his visions of a unified nation, and his legacy continues in national displays throughout Thailand.

Following 1887: The Walters’ Paintings

The Walters’ paintings are clearly related to the series of paintings from 1887, but they are not part of the original set of ninety-two. The rules of the competition limited the entries to three sizes, with which all the documented paintings from the 1887 series are consistent: small (14 5/8 by 23 5/8 in. [37 × 60 cm]), medium (17 3/8 by 30 in. [44 × 76 cm]), and large (37 by 53 1/2 in [94 × 136 cm]); large paintings ultimately constituted the exception.24 The dimensions of the Walters’ paintings match none of these three sizes, although their style resembles that of the works from the competition, as do their theme. A closer examination of the Walters’ paintings and a selection of those from the 1887 series reveals their relationship.

The posture of the elephant on the right in the Walters’ battle painting resembles that of an elephant in a painting from the 1887 series that depicts the sixteenth-century queen Suriyothai fighting the Burmese army.25 Suriyothai is a national hero in Thailand because of her efforts to defeat the Burmese (she ultimately gave her life to save the king). A second painting from the 1887 series that depicts the popular king Naresuan (1555–1605) in battle also has some important similarities to the battle painting in the Walters’ collection, especially in the massing of troops on the ground and their use of guns. 26 Neither painting is a close enough match to conclude that one artist was copying another, but the similarities suggest that the artist of the Walters’ paintings was at the very least emulating the historical themes and artistic styles of the 1887 series.

Mural of King Naresuan, Wat Suwandararam, Ayutthaya, 1931 (Photo courtesy the author)

Elephant battle scenes are described in Siamese chronicles and are central components in representing historical conflicts in Thailand, especially battles between the Siamese and the Burmese. Several of the history paintings from 1887 depict elephant battle scenes, and they likely influenced not only the Walters’ battle painting but also other works of art. One well-known example is the series of murals depicting the life and victories of King Naresuan at Wat Suwandararam in Ayutthaya, painted in 1930–31 by Phraya Anusarn Chitrakorn.27 A large elephant battle scene on the wall facing the main Buddha image (fig. 7) is clearly derived from the original chronicle paintings, and is a further demonstration of their influence on modern Thai art and the formation of Thai nationalist ideals.

The painting of the surrender in the Walters’ collection can also be traced to a lost painting from the 1887 series, which depicts a meeting between then-general Chakri (who reigned as Rama I [1782–1809]) and a defeated Burmese general.28 The meeting is described in the book Lords of Life, written by a grandson of Rama V:

An important incident occurred in 1776 when General Chakri was sent to meet a strong Burmese army encamped to the west of Phitsanulok, and more than one pitched battle took place. Although the Burmese army, under the aged commander—Maha Thihathura—was heavily defeated in the field, it was always able to regain its wellfortified camp, which General Chakri lacked sufficient forces to take by assault. One day Maha Thihathura asked for a personal meeting with the much younger Thai general, then 39. A truce was arranged and the two opposing armies were drawn up facing one another with the two commanders on horseback. After an exchange of presents, they approached each other halfway across the gap in the field. Maha Thihathura said that the days were over when the Burmese could conquer the Thais. After lauding the generalship of his opponent, the Burmese general prophesized that General Chakri had high qualities that would one day lead him to become king.29

The account aligns with the themes of the two paintings. The Walters’ painting, then, appears to be a version of this subject and helps to fill in some of the gaps from the 1887 series. The two Walters’ paintings are significant because they assert a national identity—a shift away from religious subjects and a move toward modernism.

Jean Boisselier, an influential French historian of Thai art, saw the history paintings and works that were inspired by them as an unfortunate “triumph of Western painting over the classical style” and maintained that the king’s influence “undoubtedly helped to introduce and disseminate the

Western aesthetic and Western techniques, to the detriment of Thai classicism.”30 This is too narrow a view of the paintings and their cultural significance, however. The competition was stimulating for many Siamese artists, and the presence of the paintings in the Walters’ collection is evidence of a new aesthetic, which gave rise to the production of siwilai

paintings for decades following the 1887 competition.

The style, execution, and materials of the Walters’ paintings suggest a wider audience for the paintings than the chronicle paintings commissioned by Rama V in 1887. Therefore it can be concluded that the style and subject matter of chronicle paintings spread outside of the royal family into Bangkok’s larger cultural circles. As Siamese national identity took hold, especially among the elite members of the capital, painted representations of Siamese history increased in popularity and found an audience outside of the royal family.

caption goes here

As painters worked through similar themes of depicting and displaying history in a naturalistic manner, they created a more ambiguous depiction of history. The Walters’ battle painting might in fact represent any number of actual battles from the Ayutthaya period, but its larger intent is to show the power of the Ayutthaya kings and the Siamese people. One might fault the painting’s historical accuracy or relationship to historical texts, but accuracy might not have been the artist’s principal concern.

The artists also, intentionally or not, helped to further disseminate the centralized ideas of Siamese history embraced by Rama V. In other words, the later generations of paintings embody concepts of siwilai and a general program of promoting nationalism consistent with the development of Siam as a modern nation. They were instrumental in developing a sense of Siamese identity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but we regularly see reinterpretations of these same historical themes in a variety of popular arts in Thailand today. As Thailand continues to define itself and face the challenges of new modernisms, the same historical moments are re-envisioned for the twenty-first century much as they were over one hundred years ago.

The paintings in the Walters’ collection occupy an important place in the history of Thai art. While they likely date to the early twentieth century, the Walters’ paintings bear a striking resemblance to paintings from the 1887 series commissioned by Rama V. In fact, the Walters paintings help fill an important gap in our understanding of Siamese painting at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth and document Siamese nationalism as it successfully took hold of the visual world of the court’s seat during the modern era.

Rebecca S. Hall ([email protected]) is an independent scholar.

Notes

I am grateful for the assistance of many people in formulating this essay. I would especially like to thank Hiram Woodward, Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Quincy Scott Curator of Asian Art at the Walters Art Museum from 1986 to 2004, for his enthusiasm, support, and unsurpassed ability to locate resources that helped to shed light on these paintings. I would also like to thank Dr. Woodward’s successor, Robert Mintz, for his encouragement and input. Other people without whom this essay could not have come to fruition include Pattaratorn Chirapravati, Professor of Asian Art History and Curatorial Studies at California State University, Sacramento; Pirasri Povatong, Assistant Professor in the Department of Architecture at Chulalongkorn University; and Rebecca M. Brown, Associate Professor in the Department of the History of Art at Johns Hopkins University.