Foreword to Volume 75

Clay is fundamental to creation stories across the globe: Khnum, the ancient Egyptian deity, was said to mold children from clay and place them in their mother’s womb; in Greek legend Prometheus made the first humans from clay and animated them with fire stolen from the gods; in Jewish tradition a golem fashioned from clay can be animated by written spells. Similar stories exist in African and indigenous American culture, in the Qur’an, the Hebrew Old Testament, and Hindu mythology.[1] In each case clay represents a pre-existing chaos out of which the bodies of humans are formed by an inspired or divine potter. Clay therefore has a fundamental place in global culture, and ceramics are the original material of creative expression.[2]

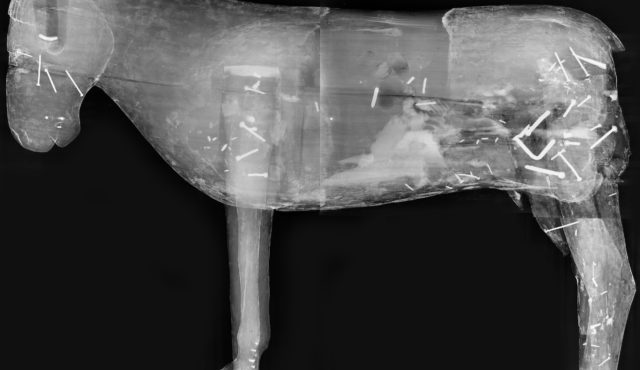

Roberto Lugo, Slave Ship Potpourri Boat, 2018, porcelain, china paint, luster. The Walters Art Museum, Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 2018, acc. no. 48.2882

As curators and academics seek an expanded vision of art history, the worldwide resonance of ceramics offers a fascinating opportunity. The Walters Art Museum recently re-committed itself to telling global and inclusive stories with its art treasures; in 2018 the museum’s nineteenth-century townhouse at 1 West Mount Vernon Place, which had been newly refurbished, was filled with a cross-departmental display of ceramics. The exhibit encompassed some of the oldest and newest objects in the collection, spanning pre-history to the present.[3] Members of the public, led by educator Herb Massie, contributed hundreds of plates, grouped to form a mosaic, while contemporary ceramicist Roberto Lugo created site-specific work reflecting on the history of the house and those that had lived and worked there, particularly the enslaved cook, Sybby Grant. Lugo’s powerful Slave Ship Potpourri Boat (fig. 1) based on a Sèvres Vase pot-pourri à vaisseau in the Walters’ collection, which was part of this installation, is discussed in this volume by Chi-ming Yang.

Historically, ceramics were a strength of the collections that now form the core of the museum. During the Gilded Age, William T. Walters (1819-1894) collected a large number of Asian, and a smaller number of European, ceramics. The most famous object he owned was an early eighteenth-century “three-string” Chinese vase, famed in the nineteenth century as the “Peach-Blow” or “Morgan” vase. Henry Walters (1848-1931), William’s son, greatly expanded this collection. Following both the aesthetic enthusiasms and prejudices of his time, he purchased Greek vases, Renaissance maiolica and della Robbia ware, Islamic lusterware, and European porcelain, as well as a great many more ceramics from Asia.[4] On Henry’s death, his collection of over 20,000 objects was given to the city of Baltimore. Since that time, major gifts have broadened the Walters’ collection to include ceramics from the ancient Americas donated by John Bourne, contemporary Japanese ceramics from the Betsy and Robert Feinberg collection, and nineteenth-century British and American majolica, the gift of Deborah and Philip English. This most recent addition, accompanied by the Englishes’ endowment of a curatorial position in the areas of decorative arts, design, and material culture, is the occasion for this special issue of the Journal of the Walters Art Museum dedicated to ceramics. It also coincides with the exhibition Majolica Mania: Transatlantic Pottery in England and the United States, 1850-1915, co-curated by Susan Weber, Director of the Bard Graduate Center, and myself, and the publication of a three-volume book with the same title, edited by a team of curators at the Bard and the Walters. Both exhibition and publication are supported by the Englishes and feature rare and exceptional works from their collection.

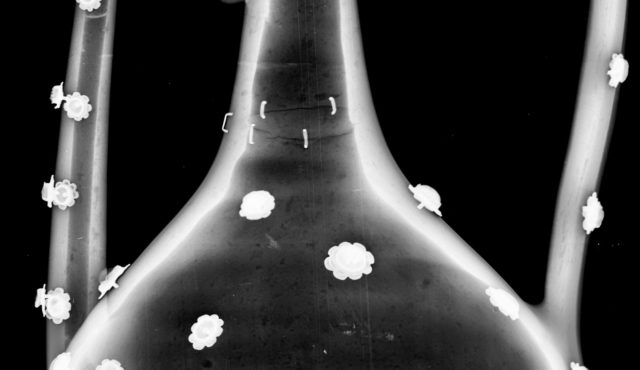

Matilda Charsley (1823-1904), designer; Minton & Co., manufacturer. Lobster Dish, 1869, glazed earthenware. The English Collection.

Majolica Mania aims to rehabilitate a ceramic type celebrated in the Victorian era, but which fell out of favor with the advent of modernism. Scholars working on the project collaborated to combine business history, labor law, studies of immigration, and the history of exhibitions and collecting, in a broad approach encompassing both the precious and the mundane. I was struck by the way that majolica, often used in spaces where nature encroached into the domestic sphere, the conservatory or kitchen, marked a boundary between raw and cooked, or clean and dirty.[5] For example, a pinkish-red lobster perches atop a majolica tureen for seafood (fig. 2), while foxgloves and leaves impressed on a flower pot hide dirt and roots (fig. 3). Essays in this volume reveal that other ceramics also perform this function of boundary marking: between species, geographies, and races, in the case of a pair of Sèvres elephant-head vases discussed by Chi-ming Yang; between the interior and exterior of the body in the case of an allegorical group of the five senses manufactured by Meissen as analyzed by Michael Yonan, and, self-consciously, even playfully, between Japanese and Chinese culture in the case of a blue-and-white vase in the form of a lotus flower, the focus of Sonia Coman’s contribution.

Minton & Co., Fern and Foxglove Garden Pot and Stand, designed ca. 1851, this example 1866, glazed earthenware. John Stacke Graham Collection

Each author in this volume takes a different approach to ceramics in the Walters Art Museum, but unifying themes emerge about global exchange and influence across medias, as well as, more abstractly, the theme of boundaries noted above. Yonan foregrounds the materiality of European porcelain through a series of close readings, which lead in a surprising direction. He boldly, but convincingly, proposes a shift in European material culture with the introduction of porcelain, akin to the shift which accompanied the introduction of one-point perspective in painting that redefined the subjectivity of the beholding individual. He writes, Europeans “created porcelain, but porcelain also created them.” Yang also reads her chosen objects closely, but also employs a kaleidoscopic range of sources, drawn from zoology, the history of science, and the pseudo-science of race, shedding light on what she identifies as “the eighteenth-century fascination with highly sensitive, racialized surfaces, from human skin to sculptural glaze.” Coman offers an in depth reading of a single object, a lotus-shaped vase. The vase is a Japanese adaptation of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain and tea culture, but the anachronic references it plays with, as well as the range of materials and types of symbols that it invokes, give it the quality of a palimpsest, which collectors, and even contemporary viewers, add to, whether the full significance of the vase’s associations are fully grasped or not.

Enjoy!

Jo Briggs

Volume Editor

With the expansion of the collection and the curatorial team at the Walters through the Englishes’ generous and transformative gifts, the stage is set for more ceramic objects, both famed and neglected, to receive the in-depth scrutiny the authors in this volume demonstrate that they merit.

[1] David A. Leeming, Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara: ABC CLIO, second edition, 2010), vol. 1, pts 1-2, “Clay based creation,” p. 312; Patricia Ann Lynch, revised by Jeremy Roberts, African Mythology: From A to Z (New York: Chelsea House, 2010), see entry “Humans, Origins of,” pp. 52-53; see also Lorena Stookey, Thematic Guide to World Mythology (Westport and London: Greenwood Press, 2004).

[2] As Michael Yonan notes in this volume, “Ceramic objects are among the oldest surviving artifacts of human history; the only tangible record we have from which to reconstruct some historically remote cultures is their pottery.”

[3] This approach has precedent at the museum: the volume Jewelry: Ancient to Modern was published in 1979, and Masterpieces of Ivory followed in 1985. See Anne Garside (ed.), Jewelry: Ancient to Modern (New York: Viking Press, and the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, 1979); Richard H. Randall, with Diana Buitron, Jeanny Vorys Canby, et al., Masterpieces of Ivory from the Walters Art Gallery (New York: Hudson Hills Press and the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, 1985). Other cross-collection projects have included a traveling exhibition of jewelry, Bedazzled: 5000 years of Jewelry (2008-2009), and a focus show, The Allure of Bronze (1995), curated by Joaneath Spicer, Murnaghan Curator of Renaissance and Baroque Art. Looking back to Henry Walters’ original displays at the museum in the early twentieth century, cases and some galleries, were organized by material.

[4] See Bill Johnston, William and Henry Walters, Reticent Collectors (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999). The vase was named for the collector Mary J. Sexton Morgan (1823-1885), and sold in 1886 at the American Art Association in New York. Johnston, Reticent Collectors, pp. 96-99.

[5] Jo Briggs, “Molding meaning: majolica in a Transatlantic context, from Cole to Haynes, from Ruskin to Eastlake,” volume 1, chapter 6 in Weber, Arbuthnott, Briggs, et al. eds, Majolica Mania: Transatlantic pottery in England and the United States, 1850-1915 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), pp. 145-171.

Editorial Board

Jo Briggs, Volume Editor

Melanie Lukas, Copyeditor

Ruth Bowler, Director of Publication and Digital Production

Lynley Herbert, Curatorial Chair

Julie Lauffenburger, Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director of Conservation, Collections, and Technical Research

Copyright 2021 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201

Special grants from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation supported scholarship and made possible the redesign and digitization of the Journal.

This publication was made possible through the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Fund for Scholarly Research and Publications, the Sara Finnegan Lycett Publishing Endowment, and the Francis D. Murnaghan, Jr., Fund for Scholarly Publications.