In late 2017, two of the five mummy portraits in the collection of the Walters Art Museum, a portrait of a man (fig. 1) and a portrait of a woman (fig. 2), underwent six weeks of high-resolution imaging and spectroscopic investigation to support an international research initiative called the Ancient Panel Paintings: Examination, Analysis, and Research (APPEAR) project.[1] APPEAR focuses on the scientific examination of mummy portraits to identify and characterize constituent materials, including the wood, pigments, paint binders, embalming resins, cloth, and even embedded sands, with the aim of complementing more than a century of art-historical research devoted to these ancient wood panel paintings.[2] The assessment— in which art-historical study and conservation science, in addition to objects and paintings conservation, all contributed to the process–has revealed that these two mummy portraits were painted with very different artistic approaches.

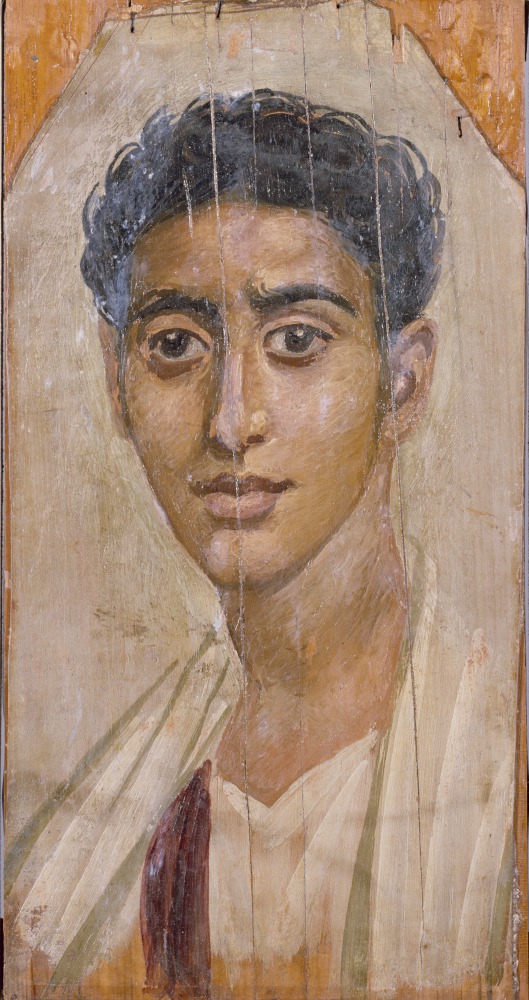

Mummy Portrait of a Man. Roman Imperial Egypt, late 1st century CE. Encaustic (wax and pigments) on wood, 15 1/2 × 8 1/16 in. (39.4 × 20.5 cm). Bequest of Henry Walters, 1931, acc. no. 32.3

Mummy Portrait of a Woman. Roman Imperial Egypt, 2nd century CE. Encaustic (wax and pigments) on wood, 17 5/16 × 7 7/16 in. (44 × 18.9 cm). Bequest of Henry Walters, 1931, acc. no. 32.5

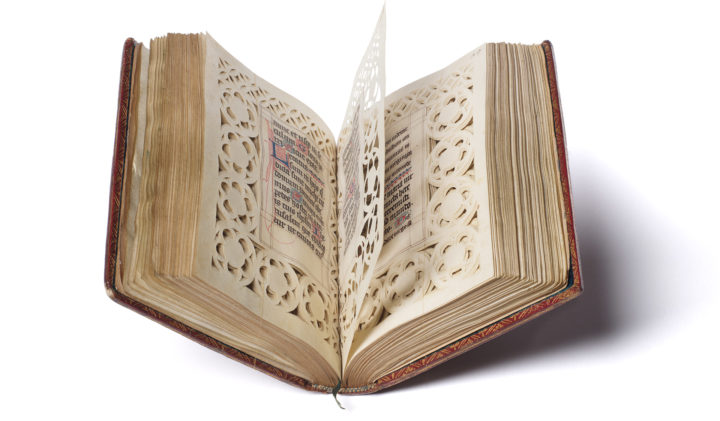

Approximately one thousand mummy portraits are known worldwide, and most were unearthed in the nineteenth century without documentation of provenience.[3] These paintings, sometimes referred to as Faiyum portraits after the region where most have been found, were intended to be mounted onto mummies in Roman Egypt (30 BCE–fourth century CE), as shown in figure 3. The Walters’ five portraits are dated from the late first century to the late second century CE.

Fig. 3

Mummy with Cartonnage and Portrait. Roman Imperial Egypt, 120–140 CE. Tempera and gilding on a wooden panel; linen and animal glue, 69 × 17 5/16 × 13 in. (175.3 × 44 × 33 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, object no. 91.AP.6

The portrait of a man, dated to the late first century CE, depicts a beardless youth wearing a white tunic with a purple clavis, or stripe, covered by a white cloak.[4] The young man turns slightly to his left, and his face seems chiseled by dramatic contrasts of lights and shadows. The muted appearance of the white cloak and tunic, seamlessly blending with the off-white background, further accentuates the striking portrayal and the vivid colors of the flesh, hair, and the purple clavis. The portrait was excavated in 1888 by W. M. Flinders Petrie in Hawara, an ancient Egyptian burial site near Faiyum; in the same pit as the Walters portrait were the portrait and mummy of another young man, now in the British Museum.[5] The general style of the Walters portrait, with large, round eyes, full lips, and a carefully articulated nose, resembles that of other portraits from Hawara, although it is not certain whether the similarities are due to familial relations or to a shared artist or workshop.

The second portrait depicts a young woman wearing purple garments and adorned with jewelry. Her hairstyle of coiled braids dates the image to the second century CE, during the reigns of the emperors Trajan and Hadrian.[6] The woman wears expensive purple garments and green and white jewelry.[7] A portrait of a young woman at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, wearing the same or very similar emerald and pearl jewelry and painted with a pose and facial features reminiscent of the Walters’ portrait of a woman, was probably produced by the same workshop, if not by the same artist.[8] Henry Walters purchased this mummy portrait along with three others from the noted collector and dealer Dikran Kelekian in 1912. Only the general provenience of these four mummy portraits, “found at Fayoum,” was given.[9]

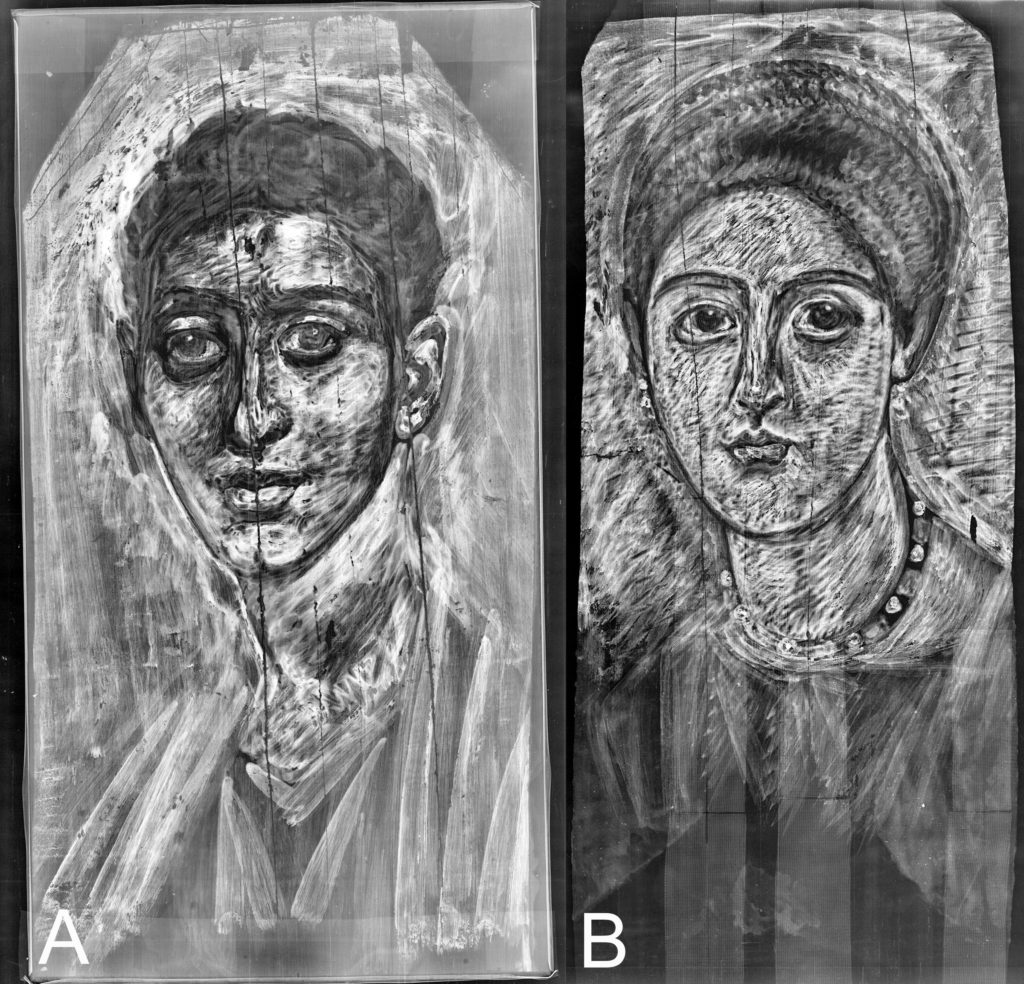

In both portraits, paint (probably wax-based) was thickly applied on a 2-centimeter-thick (0.8 in.) linden (Tilia sp.) panel.[10] Linden wood, harvested along the tree rings, yielded panels that were naturally concave, easily thinned, and smooth in surface. Though the species is not native to Egypt, it was one of the most widely used supports for portraits that were intended to fit snugly over the head of the mummy.[11] The support of the portrait of a woman retains some of its original curvature, as well as traces of embalming resin and textile fibers from attachment to its mummy. The portrait of a man, on the other hand, has been flattened, mounted onto a modern board, and coated with a thick, resinous material.[12] The past structural treatment, however, did not completely destroy clues about the portrait’s construction. Recent scientific examination identified previously undocumented vertical ridges running parallel to the wood grain throughout the panel on both the portrait of a man (fig. 4a) and on the upper-left corner of the portrait of a woman (fig. 4b). These ridges may indicate the use of planing tools and are consistent with panel preparation practices from between the late first century and the second century.

Portrait of a man (acc. no. 32.3) and portrait of a woman (acc. no. 32.5), showing vertical ridges on the wood panels (a, b) and tool marks in the paint film (c, d) visible under reflectance transformation imaging (RTI)

The particular styles of each artist start to emerge in the portraits’ preparatory layers. The portrait of a woman has a black ground, a feature quite rare in known Faiyum portraits.[13] Stereoscopic examination of the gray background in the encaustic layer revealed a wide variety of pigments, possibly indicating the use of palette scrapings to produce a more neutral tone. This layer’s appearance differs from that of the overlying wax-bound layer: it is thinly applied, weakly bound, and matte. Although the ground probably provided an even surface for subsequent paint application, it was allowed to show through the overlying paint and was used to simulate shadow in the woman’s face, neck, and clothing. The highlights and midtones of the woman’s face, on the other hand, were achieved solely through pigments; the paint is thick and opaque, comprising mixtures of yellow, brown, red, pink, and white pigments. This combined technique, relying on both the physical thinness of the applied paint and a mixture of pigments, is also observed in her green jewelry and the purple robe; the ground is visible only in the areas of the shadows. Highlights and midtones were achieved through combinations of black, brown, white, and green pigments in the jewels and bright pink to dark purple, white, and black in the purple robe. The woman’s skintone appears to have a narrower range of tones, and the transition between the lights and the darks is more subtle than that in the portrait of a man.

A different approach to tonal depth is evident in the portrait of a man. Rather than relying on a dark ground, the artist appears to have relied solely on pigments to simulate both highlights and shadows. Blue pigment adds a cooler tone to the mixture, convincingly evoking effects of shadow; stereoscopic examination revealed large blue particles, along with finer white, yellow, red, and brown particles, in the shadowed parts of the face and neck. Blue pigment was mixed in the upper layer of the man’s purple clavis for the same deepening effect. Interestingly, blue pigment particles were also found in the white of the eyes and in the thickly painted areas of the background immediately surrounding the sitter, although due to discoloration and the presence of modern coating, it is difficult to distinguish these passages from areas of the background without the pigment under the naked eye.[14] As the artist appeared to have relied solely on pigments to create a broad spectrum of tones rather than on the translucency of the layers (as seen in the portrait of the woman), the paints are consistently opaque and thick throughout the skin tone. Any variation in thickness of the paint on the portrait of a man is evident only where the elements appear flat with little to no modulation of tones, such as the robe, cloak, and the background.

Surface topography was observed using reflectance transformation imaging (RTI), a computational photographic technique that provides information about how the thick paint was applied (fig. 5). Both portraits have impasto with tool marks consistent with the use of a brush, a serrated metal tool, and a rounded metal tool, each used specific effects.[15] For example, in the portrait of a woman, the skin tones are applied with precise and repetitive rounded strokes (see fig. 4d), while a serrated tool was used in the portrait of a man to apply and manipulate skin tones using loose strokes (see fig. 4c). Parallel lines were pressed into the smooth gray background of the portrait of a woman using a rounded tool, while the white background of the portrait of a man was applied with broad brush strokes. In some cases, all three tools were used in the same area of the painting, as seen in the woman’s hair; the manipulation of the paint is clearly visible in x-radiographic examination. Both paintings showed radio-opacity corresponding with the painted image, indicating the presence of lead white throughout the paint film (figs. 6a, b).

Reflectance transformation imaging (RTI) of the portrait of a man; RTI is a computational method that enables lighting from any direction to enhance features and shapes of the applied paint.

X-radiographs of acc. no. 32.3 (a) and acc. no. 32.5, showing radio-opacity of lead-containing paint.

The distinct ultraviolet-induced fluorescence substantiated the use of wide variety of pigments and identified the presence of restoration materials in both portraits. The variations in the fluorescence in the skin tone of the woman, for example, indicated the use of at least five distinct paint mixtures for an area that appeared to be of fairly limited palette when seen under natural light (fig. 7c, d). This phenomenon was expected from the skin tone of the man, which has a more dramatic chiaroscuro. (The bright whitish-blue fluorescence of the resinous coating on this portrait, however, impeded the examination.) Ultraviolet illumination also revealed an intense orange-pink fluorescence of the purple paint, which is a characteristic response of organic pigments, in the clavis of the man and the robe and in skin tone of the woman (fig 7a, b). Only the underlying layer of purple paint on the portrait of a man fluoresced, prompting spectroscopic analysis.

Ultraviolet-induced pink fluorescence in both portraits reveals the presence of organic pigment. The painted passage with this fluorescence is marked with white arrows. Details of 32.5 in both visible (c) and ultraviolet (d) illumination show variation in fluorescence in the skin tones of the portrait of a woman.

While ultraviolet examination revealed the use of the organic pigments in both portraits, visible-induced luminescence (VIL) detected the presence of Egyptian blue, a calcium copper (II) silicate, only in the portrait of the man.[16] There was a strong infrared-luminescence in the halo around the head, the area between the eyebrows, and the proper left side of the area above the mouth, while there were only moderate responses from parts of the robe, forehead, neck, and ears (fig. 8a), all areas where blue pigment particles had been observed under the stereoscope. In comparison, there was minimal near-infrared response in the portrait of a woman, indicating little to no Egyptian blue (fig. 8b), although the use of Egyptian blue for modulation of tones has been observed in four other second-century portraits.[17]

Strong visible-induced near-infrared luminescence suggests the presence of Egyptian blue in the portrait of a man (acc. no. 32.3). There is an absence of strong luminescence in the portrait of a woman (acc. no. 32.5).

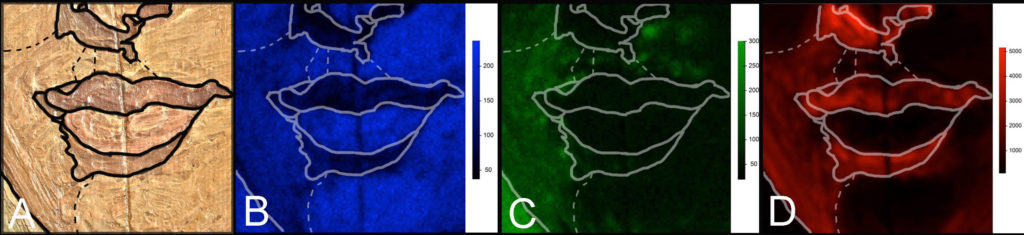

Elemental mapping confirmed discoveries made through the non-invasive imaging techniques previously described. For instance, elemental analysis of the purple paint confirmed the presence of an organic pigment and identified it as madder lake.[18] Although fluorescence indicating the presence of madder lake pigment was limited to the underlying layer, spectroscopic analysis revealed high contributions from aluminum and potassium in all paint layers of the man’s clavis; similarly, the purple robe of the woman had a high contribution from aluminum, which along with potassium-aluminum sulfate, was a mordant used on madder dyes.

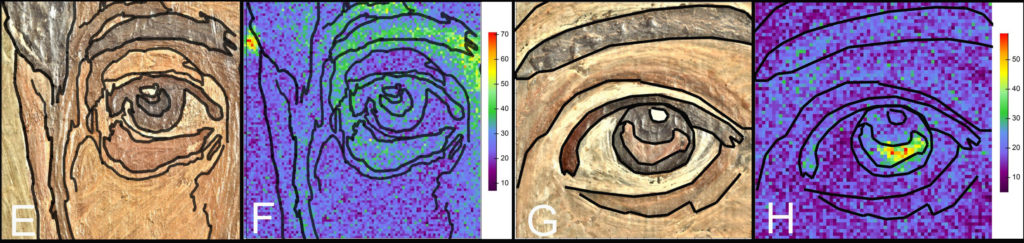

The high levels of copper confirmed the blue pigments as Egyptian blue in the portrait of a man, as previously indicated by stereoscopic and VIL examination. The portrait’s highlights had the highest contributions from lead, iron, and silicon; the large area of shadows, due to the presence of Egyptian blue, had the highest reading of copper with substantially less contribution from lead white (figs 9a–d). On the evidence of elemental mapping and point-analysis, Egyptian blue was also present in the deep purple layer of the clavis, despite the lack of luminescence in VIL.[19] Moreover, its presence in the white background, which has also been observed in the white cloak of another mummy portrait, probably had a brightening effect.[20] This intended haloed effect around the head of the man, however, has been lost over time due to discoloration and the addition of restoration materials.

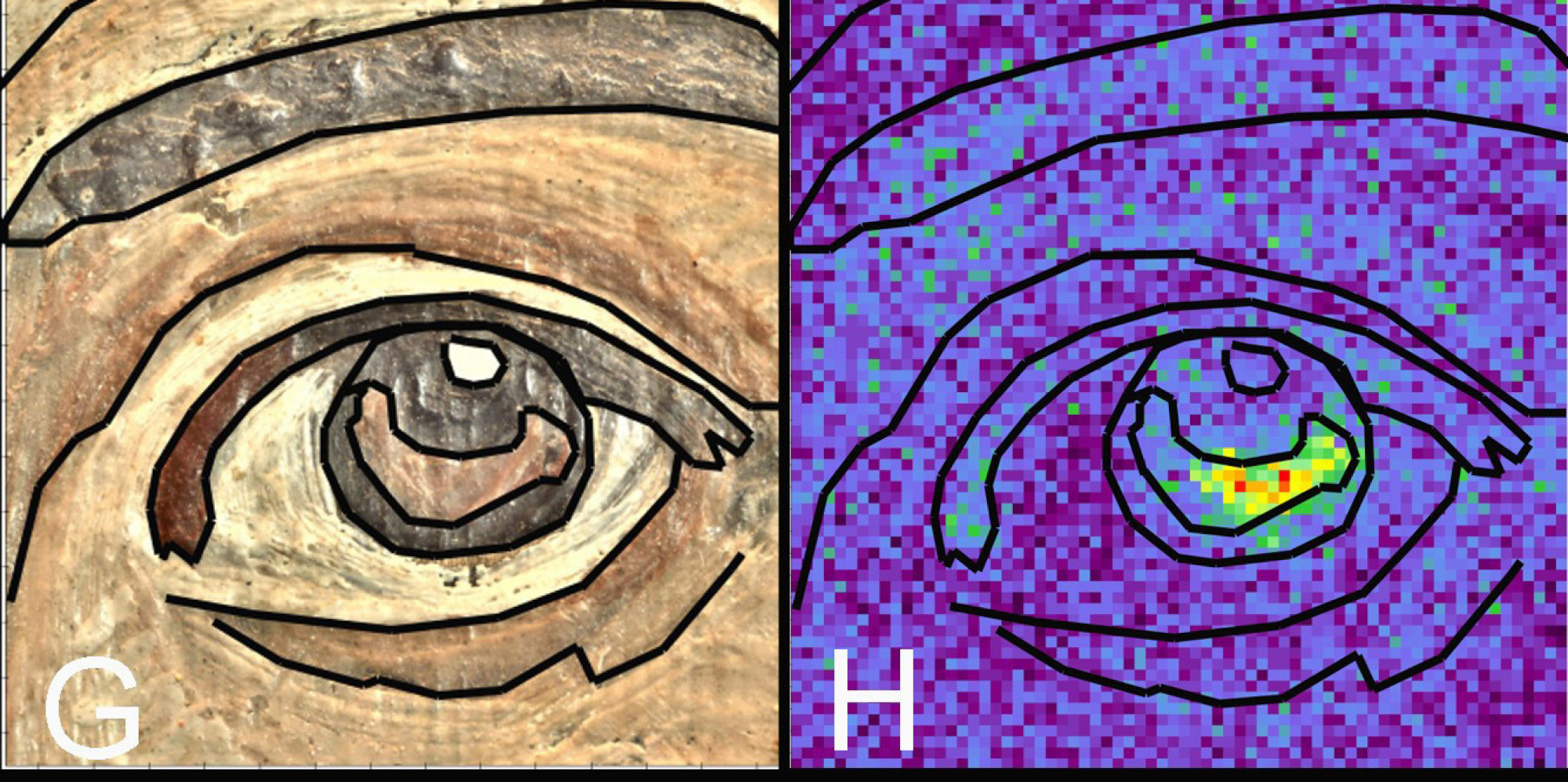

Elemental maps of the man’s right cheek (a) show a high contribution from lead (b) in the areas in highlight; high contributions from copper (c) and iron (d) in the shadowed areas.

The second set of normal light images and the corresponding elemental maps show the selective and deliberate application of umber (as indicated by the presence of manganese) in both the man (e–f) and the woman (g–h).

The ample use of the Egyptian blue in the portrait of a man prompted analysis of the green pigments. The primary pigment used for the dark greenish shadow in the robe of the Man was terra verte, an iron-earth pigment traditionally a part of the pharaonic palette. However, the necklace in the portrait of a woman was achieved through a copper-based green pigment excluding Egyptian green.

Finally, while there appeared to be considerable differences in the type and application of those paint mixtures, both portraits employed several shades of brown, with varying proportions of iron-earth pigments, carbon black, and lead white. The use of umber, as suggested by the presence of manganese, was visually indistinguishable but, where detected, appeared to have been extremely selective, being found only in the iris, nose, and between the lips of the woman and the two strokes above the man’s eye (Figs. 9e–h).

It is through a close, critical examination of each portrait that the individual hands of the artists become apparent, each with unique materials, methods, and techniques. The painters of both portraits employed pigments in common use in Roman Egypt, including lead white, iron-earth pigments, and madder lake. Commonalities can also be found in the panel preparation: the same toolmarks, which had not been noted previously within the APPEAR database, are present on both portraits, suggesting that preparation of the supports might have been governed by standardized practices. However, although the same tools were used for applying paint on both portraits, the use of assorted tools and the manipulation of the paint are especially discernible in the portrait of a woman, allowing the dark ground to show through and convey tonal depth. Tonal depth in the portrait of a man was achieved by adding Egyptian blue. The approach to tonal variation emerges as a major difference between the two paintings. Seeing these similarities and deviations between not only the two Walters portraits but also among those found in collections around the world emphasizes the unique nature of the Faiyum mummy portraits and the techniques of their makers. Much remains to be learned about these ancient art works.

Hae Min Park ([email protected]) is the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Paintings Conservation at the Worcester Art Museum of Art; Amaris Sturm ([email protected]) is the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Objects Conservation at the Cleveland Museum of Art; Glenn Gates ([email protected]) is the Conservation Scientist at the Walters Art Museum; Lisa Anderson-Zhu ([email protected]) is Associate Curator of Art of the Ancient Mediterranean, 5th Millennium BCE to 4th Century CE, at the Walters Art Museum.

[1] In addition to the two portraits that are the subject of this note, the Walters’ holdings of mummy portraits comprise a portrait of a bearded man (acc. no. 32.6); a portrait of a woman (acc. no. 32.4), and another portrait of a woman (acc. no. 32.7).

[2] APPEAR was initiated in 2013 by Marie Svoboda, Associate Conservator of Antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum. The Walters Art Museum has been working alongside the British Museum, London; the Ny Carlsberg Glypotek, Copenhagen; the Phoebe Hearst Museum of Anthropology, Berkeley; the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford; and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, as one of seven original participating institutions. The present number of participating institutions exceeds thirty and includes the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London; and the Berlin State Museums. For details on the project, see: http://www.getty.edu/museum/research/appear_project/

[3] See Klaus Parlasca and Hans G. Frenz, Ritratti di mummie. 4 vols. Repertorio d’arte dell’Egito greco-romano, ed. Nicola Bonacasa, Series B (Rome, 1969–2003); see also Klaus Parlasca and Helmut Seeman, Augenblicke: Mumienporträts und ägyptische Grabkunst aus römischer Zeit, exh. cat. Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt (Munich, 1999).

[4] The Walters portrait of a man was in the collection of H. Martyn Kennard until its sale through Sotheby’s, London, in 1912; it was acquired by Henry Walters in 1913. See Catalogue of the Important Collection of Egyptian Antiquities Formed by the Late H. Martyn Kennard, Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, London, July 16–19, 1912, lot 541.

[5] British Museum EA74707 (registration no. 1994,0521.5), presented by H. Martyn Kennard to the National Gallery, London, in 1888; transferred to the British Museum 1994. See Paul Roberts and Stephen Quirke, “Extracts from the Petrie Journals,” in Living Images: Egyptian Funerary Portraits in the Petrie Museum, ed. Janet Picton, Stephen Quirke, and Paul Roberts (London, 2006), 83–104 at 91.

[6] For a discussion of the hairstyle, see Barbara Borg, Mumienporträts: Chronologie und kultureller Kontext (Mainz, 1996), 38–48.

[7] For a discussion of purple textiles in antiquity, most often associated with deities and rulers, see Kenneth Lapatin, Luxus: The Sumptuous Arts of Greece and Rome (Los Angeles, 2015), 187–89.

[8] Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (acc. no. 09.181.7), purchased in 1909 from Maurice Nahman, Cairo. For an example of the same necklace possibly appearing in different portraits, compare paintings from the Walters Art Museum (acc. no. 32.4) and Detroit Institute of Arts (acc. no. 25.2).

[9] Kelekian purchase book, 1912, Walters Art Museum Archives. For the other portraits, see note 1.

[10] Species identification of the support of the portrait of a man was completed in 1967 by the U. S. Department of Agriculture in Madison, WI; the identification of the support of the portrait of a woman is based on the overall appearance and comparable examples.

[11] According to a study published by the Musée du Louvre in 2008, approximately 64 percent of the museum’s panels were on linden wood. See Marie-France Aubert, Portraits funéraires de l’Egypte romaine: Cartonnages, linceuls et bois (Paris, 2008), 40. For a discussion of panels made from other wood species and possible reasons for these choices, see Caroline Cartwright, Lin Rosa Spaabaek, and Marie Svoboda, “Portrait Mummies from Roman Egypt: Ongoing Collaborative Research on Wood Identification,” British Museum Technical Research Bulletin 5 (2011): 54–56.

[12] In his excavation note, Petrie stated that it was in “excellent condition but much split; it will join up all right, however,” suggesting that the portrait might have been affixed to an auxiliary support soon after the excavation, perhaps even by Petrie himself. See Roberts and Quirke, “Extracts from the Petrie Journals,” 91.

[13] The portrait of a young woman at the Metropolitan Museum (see note 7 above), stylistically similar to the Walters portrait of a woman, also has a dark background. See Euphrosyne Doxiadis, The Mysterious Fayum Portraits (New York, 1995), 218 (no. 96): “The way it [her complexion] has been built up from a dark background is a perfect example of the technique later used in icon-painting.”

[14] As suggested by previous assessments of mummy portraits conducted at the Northwestern University, the blue pigment was likely added to white or gray paints for its properties: “We are speculating that the blue has a shiny quality to it, that it glistens a little when the light hits the pigment in certain ways. . . . The artist could be exploiting these other properties of the blue color that might not necessarily be intuitive to us at first glance.” Megan Fellman, “Rare Use of Blue Pigment Found in Ancient Mummy Portraits: Northwestern-Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collaboration Reveals Hidden Color,” Northwestern Now, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, August 26, 2015.

[15] For a detailed discussion of different tools, see David L. Thompson, The Artist of the Mummy Portrait (Malibu, 1976), 35.

[16] Visible-induced luminescence involves exciting the metal ions of the pigment with light from the visible range of the electromagnetic spectrum and capturing the resulting near-infrared emission. The degree of resulting luminescence is roughly proportional to the amount of pigment present in the mixture. The technique has been used in detecting and mapping the presence of copper-based pigments such as Egyptian blue and its derivatives, and cadmium-based pigments. For further information on the technique, see Barbara H. Stuart, Analytical Techniques in Materials Conservation (Chichester and Hoboken, NJ, 2007), 163–66.

[17] Fifteen second-century portraits and panel paintings were analyzed by Northwestern University and the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology in 2015. Their examination has revealed that “the ancient artists used the pigment Egyptian blue as material for underdrawings and for modulating color.” See Fellman, “Rare Use of Blue Pigment Found in Ancient Mummy Portraits.”

[18] Documented use of aluminum and potash-alum does not occur before the Greco-Roman period in Egypt. Before Greco-Roman occupation, Egyptian madder dyes were used primarily for dyeing textiles, leather, and hair and were typically mordanted with calcium sulfate. See Aubert, Portraits funéraires de l’Egypte romaine, 48.

[19] The lack of luminescence is a topic for future study. The deep tone of the mixture might have been intended to imitate the prized Tyrian purple dye. See Aubert, Portraits funéraires de l’Egypte romaine, 50.

[20] The addition of a blue pigment reflects more blue and purple, which essentially counteracts yellowing and yields a whitening effect. This technique appears to have been used in another mummy portrait at the Walters, Portrait of a Woman (acc. no. 32.4), as suggested by the visible-induced near-infrared luminescence from the woman’s white robe.