Seeing Codicologically: New Explorations in the Technology of the Book

Do you know how to use a codex? Of course you do! A codex is a book. You open the cover, read the first page, turn it, read the next page, and so on. It would seem simple enough, but of course not every book works in precisely this way. Think of a dictionary, or a child’s “choose your own adventure” book, both of which are explicitly designed not to be read in a linear fashion. Think of a travel guide with foldout maps or a Torah scroll that requires unfurling. Think about the webpage on which this journal issue appears, as you click on links and open new tabs. There are many ways a book might be designed to be used, and more ways that it might be used unexpectedly. Historically, research on decorated medieval manuscripts has tended to see the codex form of books as “normal” and to assume that the books were used linearly, if use was considered at all. Scholars have often considered individual illuminated pages as stand-alone images divorced from their material context, although more recent studies have emphasized the “opening”–two pages that face each other when a codex is open–as a crucial structural framework for understanding the interplay between words and images in manuscripts. Current scholarship has also reminded us that medieval manuscripts are more than words and images and certainly more than just codices: they are parchment, paper, textiles, wood, leather, metal hardware, and even the physical traces of the humans who have leafed through them, made annotations and erasures in them, hidden things within their pages, and kissed them.

Essays

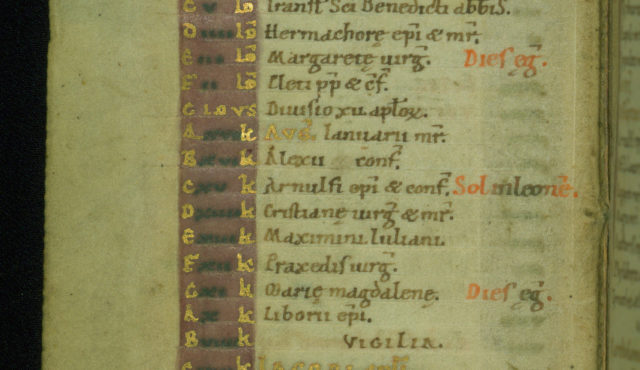

A Codicological Cloister for Claricia

Benjamin C. Tilghman

Looking through Books

Nicholas Herman

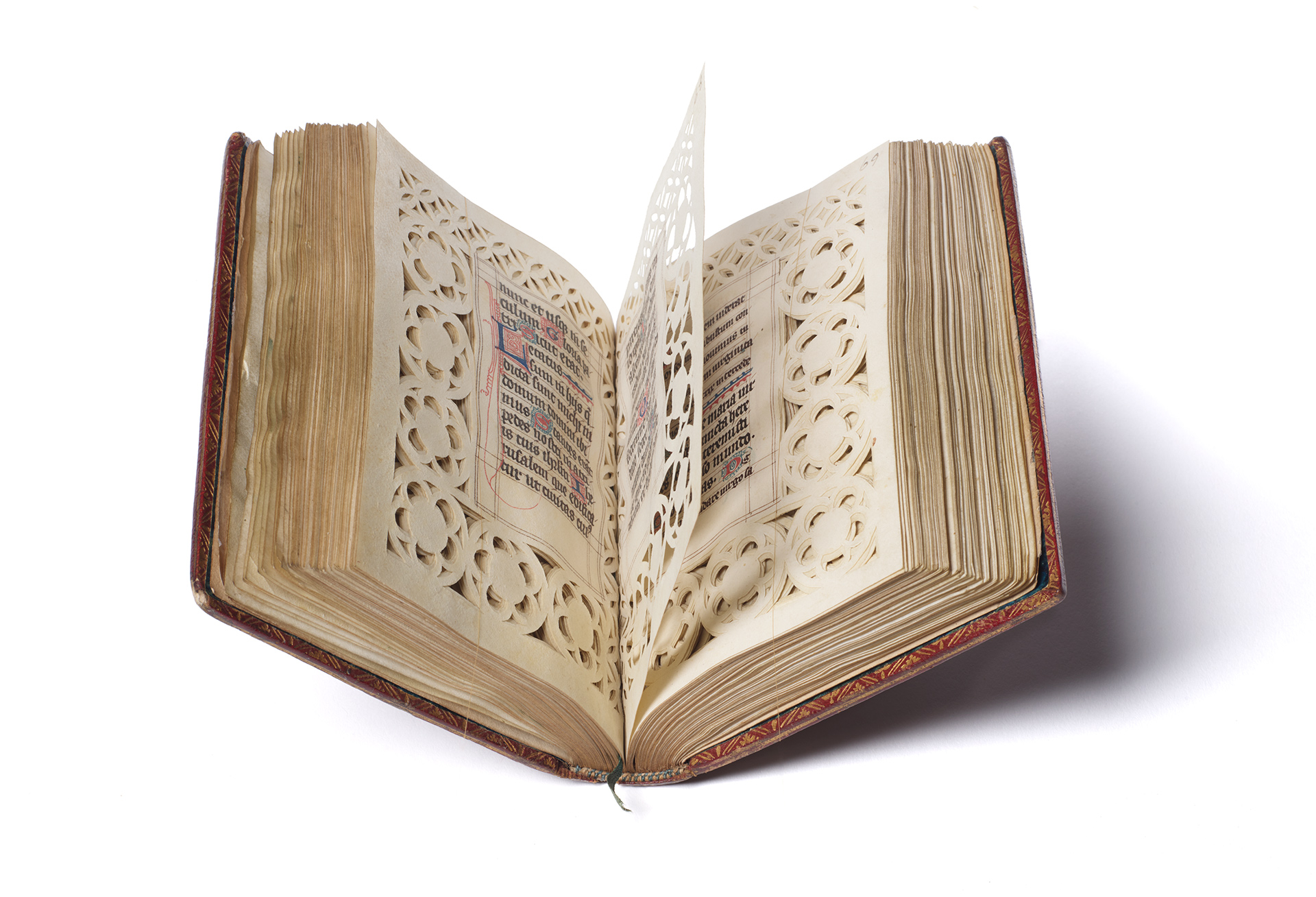

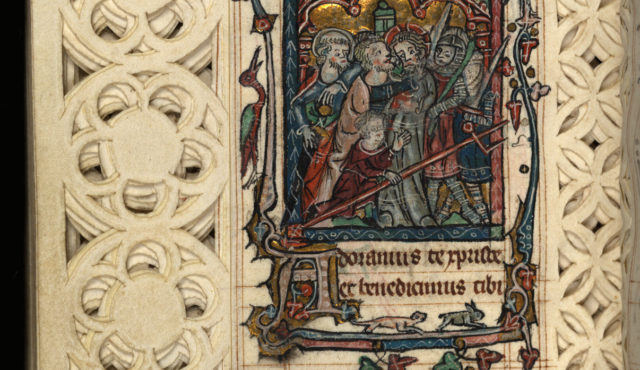

A Cut Above the Rest…? Unraveling the Mystery of the Walters “Lace” Manuscript

Lynley Anne Herbert

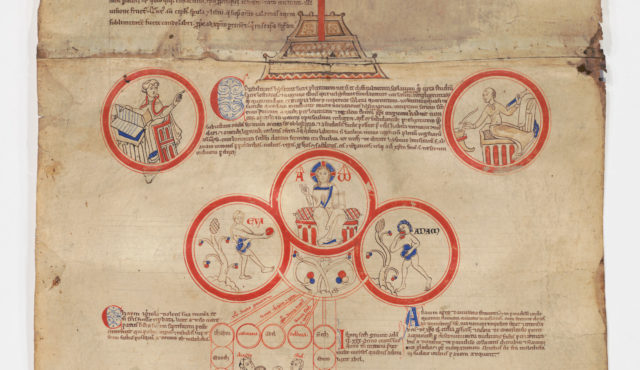

“The Rollodex: An Experiment around the Prepositional Paradigm through Peter of Poitiers’s Genealogia Christi”

Sonja Drimmer

Exploring Sensuls: An Indigenous Manuscript Tradition in Ethiopia

Christine Sciacca

The Kennicott Bible’s Codicology and Its Implications

Adam S. Cohen

Portraiture and Presence in the Helmarshausen Psalter

Shirin Fozi

Paint it Black: An Unusual Prayer Book Illuminated by the Masters of the Dark Eyes, ca. 1510

Kathryn M. Rudy

Notes

An Obscenely Humorous Sam Wide Group Kylix at the Walters Art Museum

Lisa Anderson-Zhu

Léon Bonvin’s Landscapes with Figures, Japanese Prints, and the French Etching Revival

Jo Briggs

1451: Saint Jerome in Fabriano

Stanley Mazaroff