Seeing Codicologically: New Explorations in the Technology of the Book

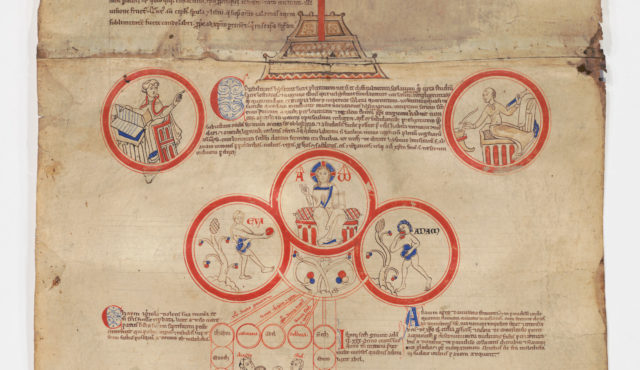

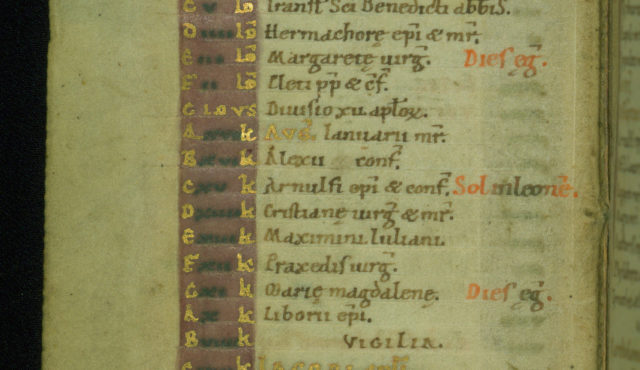

Do you know how to use a codex? Of course you do! A codex is a book. You open the cover, read the first page, turn it, read the next page, and so on. It would seem simple enough, but of course not every book works in precisely this way. Think of a dictionary, or a child’s “choose your own adventure” book, both of which are explicitly designed not to be read in a linear fashion. Think of a travel guide with foldout maps or a Torah scroll that requires unfurling. Think about the webpage on which this journal issue appears, as you click on links and open new tabs. There are many ways a book might be designed to be used, and more ways that it might be used unexpectedly. Historically, research on decorated medieval manuscripts has tended to see the codex form of books as “normal” and to assume that the books were used linearly, if use was considered at all. Scholars have often considered individual illuminated pages as stand-alone images divorced from their material context, although more recent studies have emphasized the “opening”–two pages that face each other when a codex is open–as a crucial structural framework for understanding the interplay between words and images in manuscripts. Current scholarship has also reminded us that medieval manuscripts are more than words and images and certainly more than just codices: they are parchment, paper, textiles, wood, leather, metal hardware, and even the physical traces of the humans who have leafed through them, made annotations and erasures in them, hidden things within their pages, and kissed them.

In October 2019, scholars gathered for a two-day workshop at the Walters Art Museum and Johns Hopkins University to consider medieval manuscripts as complex technologies that could be used in many different ways, some intended and others unexpected.[1] The Walters, as a repository for an extraordinarily rich collection of nearly 1,000 manuscripts and a leader in the field of book digitization, provided an ideal environment in which to explore new approaches to understanding these unique objects, while the professors and students in the department of the History of Art at Johns Hopkins’ have long been important intellectual partners in the field of medieval art and manuscripts. The workshop brought together scholars whose research explored unusual manuscripts in creative and non-traditional ways, as well as “conventional” manuscripts in unconventional ways, with the goal of discussing their work in a spirit of collaboration and shared discovery.[2] Those explorations, and the lively conversations that the gathering inspired, resulted in the essays in this volume of the Journal of the Walters Art Museum, and feature groundbreaking work on manuscripts from the Walters collection and beyond. We hope that with these essays we have taken another step toward better understanding of the structural capacities of manuscripts and how they worked to produce meaning and social value among their beholders.

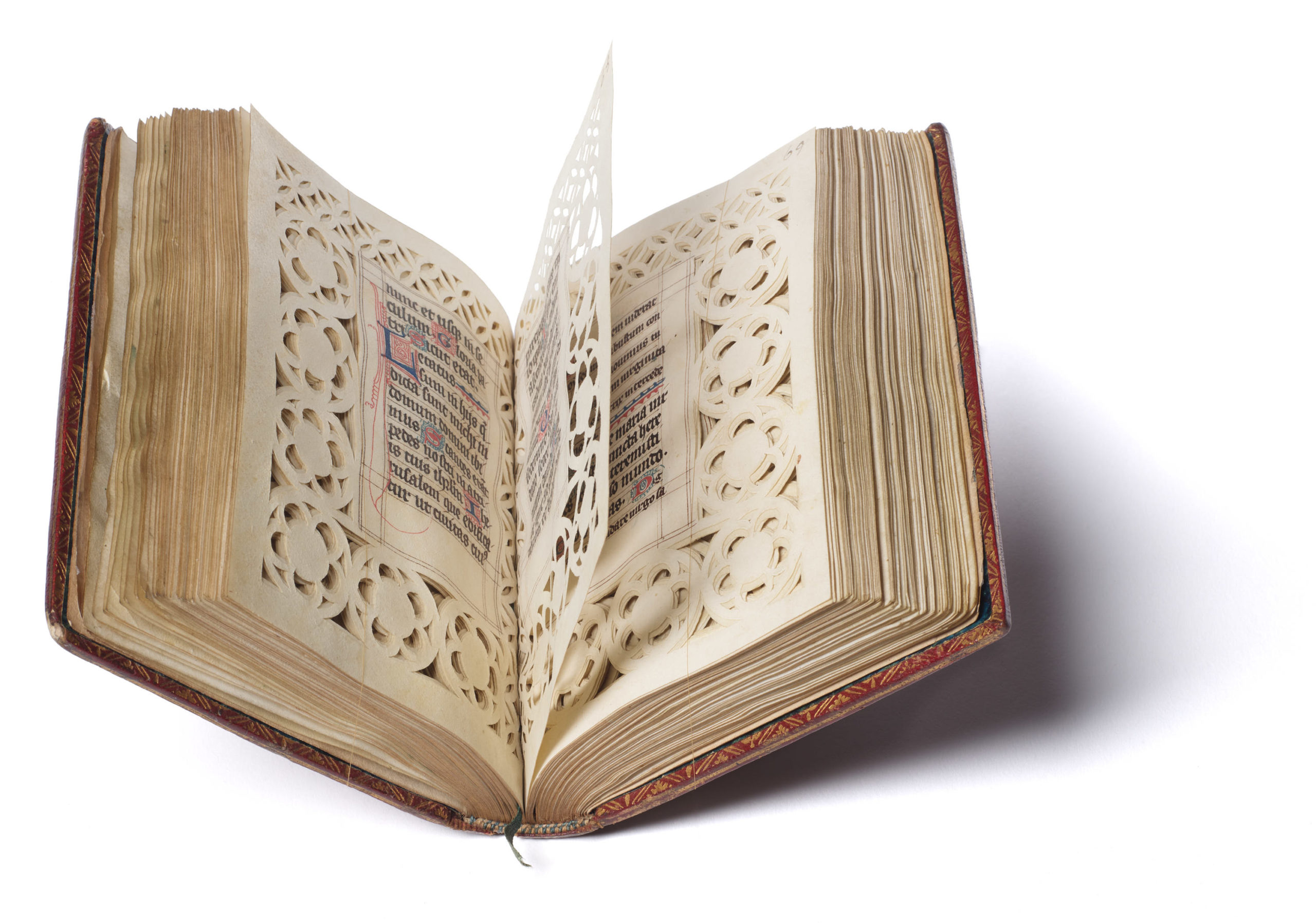

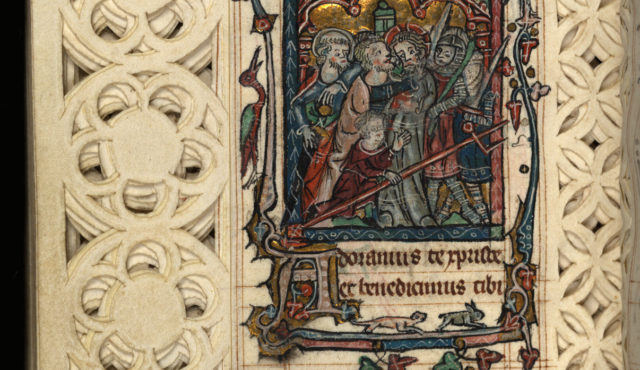

The first three essays consider transformation of the page, whether through the interactions of images and words as the book is opened and closed or by making physical alterations to the page. Just as scholars often talk about “openings,” Benjamin Tilghman considers how illuminations can interact and take on new and poignant meanings as they come together in “closings,” while Nicholas Herman contemplates how viewers can be privy to internal conversations between a book’s illuminations by means of openings cut through the pages. Lynley Herbert examines cutting in a different way, exploring how parchment could be transformed into something evoking lace, or even deeply chiseled stone.

The assumption that the standard codex is the ideal structure of medieval books is reconsidered in Sonja Drimmer’s discussion of the coexistence of the same text in both roll and codex forms and Christine Sciacca’s examination of how folding devotional imagery found in Ethiopian sensuls takes on the codex form but does not function as one. A book’s structure can also be unusual in less overt ways, as Adam Cohen notes in the discussion of a Hebrew Bible that has been “wrapped” in another text to create a complex and deeply meaningful experience for the reader. Stepping back and looking at illuminations from a different perspective can also be enlightening, as Shirin Fozi-Jones demonstrates by reframing of Romanesque “portraits” as avatars or representatives for generations of the book’s users, while Kate Rudy investigates the results of artists’ attempts to imitate novel forms of book decoration without fully making use of the techniques involved.

The idea for this project emerged in part in response to the spread of digitization and new media initiatives in manuscript studies, and across our multimedia environment more broadly. Digitization has made manuscripts accessible to audiences of many backgrounds around the world, and they have enhanced scholars’ research by making our objects of study more widely available. Yet, as many have argued, the digital surrogate and the original manuscript are themselves different kinds of objects. As the digital has taken center stage in academia as well as an increasingly important place in museums, scholars have turned newly appreciative eyes to the material properties of the non-digital object, recognizing that the future of manuscript studies rests in the ability of scholars to use new technology in concert with the exploration of the physical books. Publishing these findings in a digital journal is a way to take advantage of the best aspects of these new technologies, allowing this scholarship to reach a broader audience, and providing that audience opportunities to explore these manuscripts along with us. We hope you will enjoy that journey, and that it will spark a new sense of wonder and appreciation for quirky codicology!

Lynley Anne Herbert, Walters Art Museum

Benjamin C. Tilghman, Washington College

Sonja Drimmer, UMass-Amherst

[1] Workshop participants, many of whom contributed essays to this volume of the journal, included Adam S. Cohen, Sonja Drimmer, Shirin Fozi, Lynley Herbert, Nicholas Herman, Christopher Lakey, Kathryn M. Rudy, Alexa Sand, Christine Sciacca, Benjamin Tilghman, Nino Zchomelidse. Special thanks to Abigail Quandt, Walters Head of Books and Paper conservation, who generously shared with participants her deep knowledge of the collection and of medieval manuscripts in general.

[2] This workshop would have been impossible to plan and execute without the assistance of the Walters’ staff, especially Diane White, administrator to the executive office, who made all of the arrangements for the participants. We are also grateful for the assistance of Ashley Costello, Senior Administrative Coordinator in the Department of the History of Art at Johns Hopkins University, and for the funding and hospitality provided by the JHU Department of the History of Art. Additional funding was graciously provided by the Mellon Society of Fellows in Critical Bibliography.

The citation for the essay portion of this volume is:

Lynley Anne Herbert, Benjamin Tilghman, and Sonja Drimmer, eds, Seeing Codicologically: New Explorations in the Technology of the Book. The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 76 (2023), https://journal.thewalters.org/volume/76/essay/looking-through-books/

Editorial Board

Lynley Herbert, Volume Editor

Sonja Drimmer and Benjamin C. Tilghman, Guest Volume Editors

Melanie Lukas and Lisa Anderson-Zhu, Copyeditors

Ruth Bowler, Director of Publication and Digital Production

Lisa Anderson-Zhu, Associate Curator of Art of the Mediterranean

Julie Lauffenburger, Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director of Conservation, Collections, and Technical Research

Copyright 2023 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland, 21201

This volume was made possible through the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Fund for Scholarly Research and Publications, the Sara Finnegan Lycett Publishing Endowment, and the Francis D. Murnaghan, Jr., Fund for Scholarly Publications.

The redesign and digitization of the Journal was made possible by a grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.