Introduction

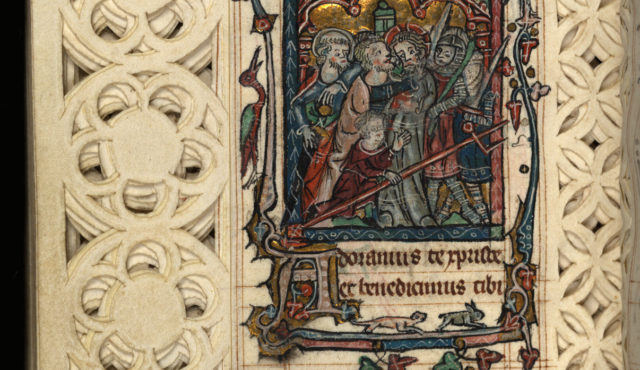

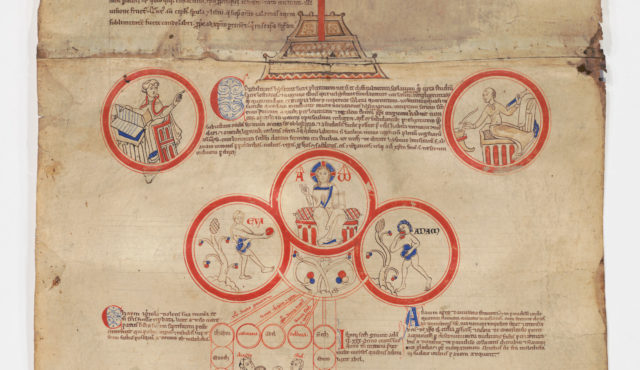

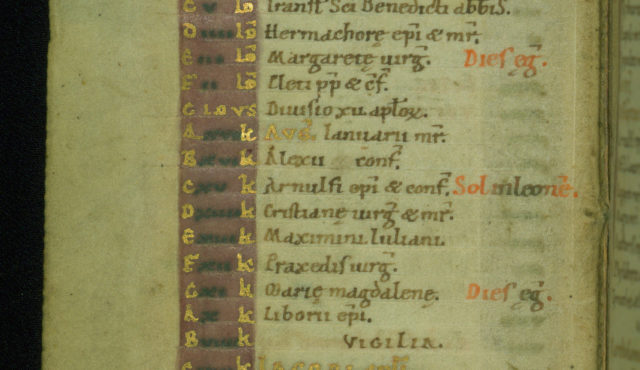

Among the many remarkable manuscripts in the collection of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, is an Austrian or Bohemian Bible completed on February 2, 1507 (acc. no.W.805). It contains the first eight books of the Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, and Ruth), and each book opens with a painted initial inserted into one of the two text columns and equal in height to eleven lines of text. The exception is the picture for Genesis, a magnificent composition as wide as both text columns and as high as twenty-two lines of text, taking almost two-thirds of the page; below it are the first twelve lines of Genesis. In the square frame, with personifications of the four winds or elements in the corners, a series of medallions signify the cosmos: the outermost ring is filled with angelic beings, culminating in a bust of Jesus at the top that gives the whole image a Christian cast. In the center God the Father completes the Creation of the World by bringing forth Eve from Adam’s side in a luxurious Garden of Eden populated by varied animals.[1] In its placement, size, and iconography, the picture makes a fitting beginning to the Bible—except that it isn’t the beginning of the book. The Genesis picture is on fol. 6v and is preceded by several folios that contain preliminary material, namely the letter by Jerome to Paulinus (encouraging the bishop of Nola to study the Bible), and Jerome’s prologue (in which he defends translating into Latin the Pentateuch—the first five books of the Bible). These and similar texts were a staple of many Bibles by the fifth century. An especially common device was the series of Eusebian canon tables, a concordance of Gospel readings often set within architectural frames.[2] Many of these preliminary texts contain illuminations or other visual elaborations; Walters W.805 features a historiated initial depicting Jerome reading a book in his study. The Walters manuscript shows that while the Bible begins “in the beginning,” Bibles as books often began with other texts and pictures that situated the sacred text in particular historical and theological contexts.

Christian Bibles were not the only ones made in this way. Just thirty-one years before W.805 was completed, a Hebrew Bible was finished on July 24, 1476, in the northwestern Spanish city of La Coruña (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, acc. no. MS Kennicott 1, the “Kennicott Bible”).[3] A colophon (a text, usually at the end of a manuscript, with information about its production) records that it was written by a scribe named Moses ibn Zabara and destined for “Isaac, son of the honorable, esteemed Don Solomon of Braga.”[4] A second, short decorated colophon indicates that the lavish book was decorated by Joseph ibn Hayyim. We know nothing about these individuals except what we can derive from the book itself, which was one of many Hebrew Bibles produced by and for Iberian Jews between 1100 and 1500. Currently known as the Kennicott Bible, after the eighteenth-century Oxford Hebraist and librarian whose collection is part of the Bodleian Library,[5] this book is one of the most sumptuous surviving examples of medieval Hebrew Iberian Bibles and has often been studied by art historians. In this essay, I consider what the codicology of the Kennicott Bible reveals about its production process and the ideological messages crafted by its creators.

The Kennicott Bible: A Brief Description

With 459 folios of exceptional parchment, and enclosed in a tooled box binding with colorful parchment pastedowns in front and back, the manuscript contains the entire Hebrew Bible (fols. 9v–437v) as well as Sefer Mikhlol (Book of Perfection), a grammatical treatise written ca. 1210 by Rabbi David Kimhi (or Qimhi, also known by his Hebrew acronym as the Radak, ca. 1160–1235). This treatise was positioned at the front and back of the manuscript on fols. 1v–8v and 438v–444r.[6] Extensive masoretic notes—traditional, detailed lexigraphic information—were included in the three empty vertical spaces that flank the two text columns (the so-called masorah parva) and in the upper and lower margins of each Bible page (the so-called masorah magna).[7] The masorah magna was occasionally written in geometric configurations and embellished with pen flourishes and/or gilt, which are among the many visual elaborations found throughout the book. The most striking are seven full-page “carpet pages,” and two pages that depict Temple implements. More regularly, the ends of each biblical book, and the divisions of the psalms, are all marked by panels that recall the abstract decoration of the “carpet pages.” The psalm numbers, as well as the marginal parashah markers that indicated the weekly biblical readings for the liturgy, were variously executed in paint, gilt, or pen flourishes (many include fantastic beasts or hybrids). It is not possible to do justice here to the richness of Kennicott’s decoration; in the present context it should be noted only that, in planning the layout of the Bible, Moses ibn Zabara and Joseph ibn Hayyim carefully used visual devices to distinguish the book’s different parts.[8]

The richly decorated frames that contain the text of Sefer Mikhlol, fifteen pages at the beginning of the book and twelve at the end, are noteworthy because of their placement, the density and inventiveness of their ornament, and the liberal use of gold and silver. The text is written in two columns in the shape of pointed or rounded architectural columns enhanced by the painted or gilt frames that enclose the text. These in turn are surrounded by a large rectangular frame for the page as a whole, and the space in between is filled with elaborate and colorful pen flourishes, ornamental patterns, and sometimes large creatures both real and fantastic; additional flourishes around the outer rectangular frame add a final decorative touch.

The Codicology of the Kennicott Bible

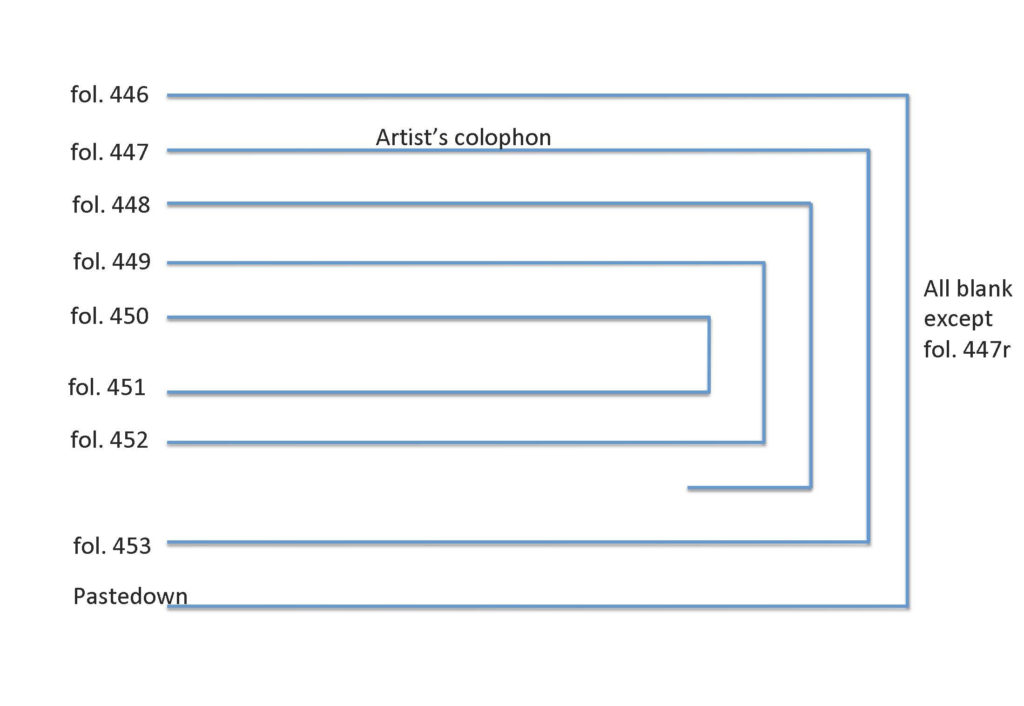

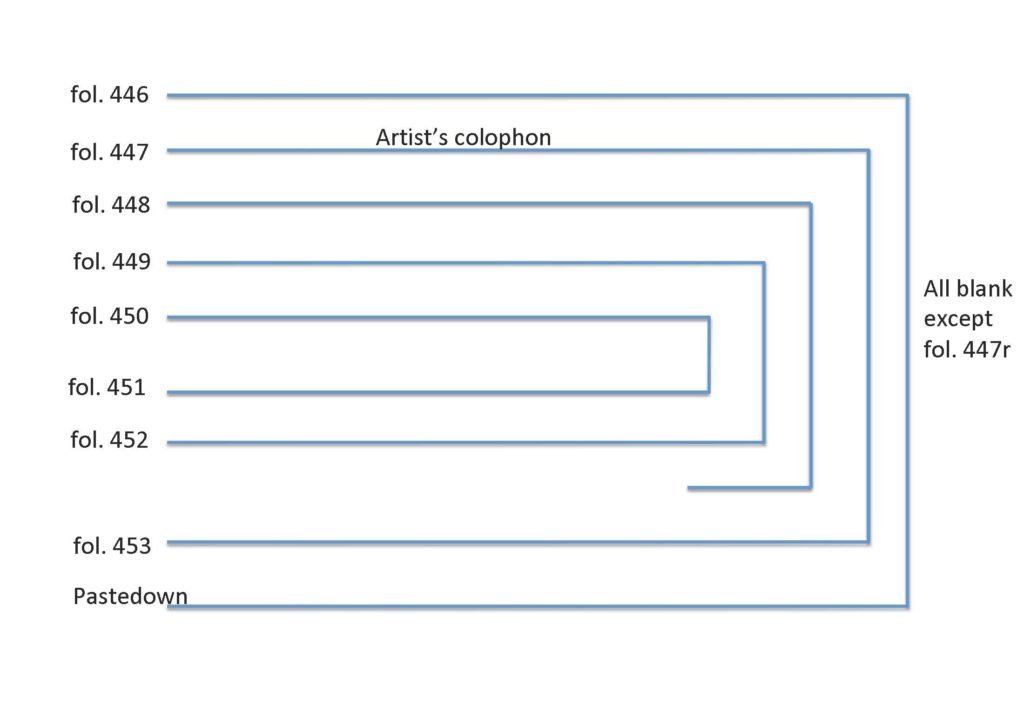

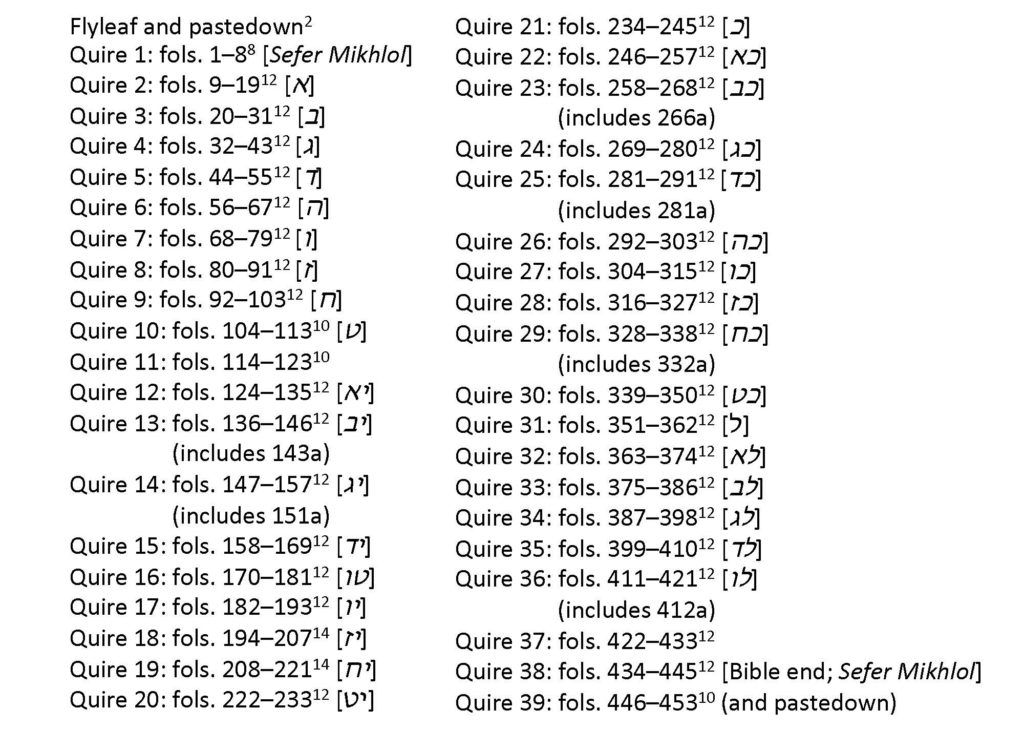

Fig. 1 List of Quires in the Kennicott Bible

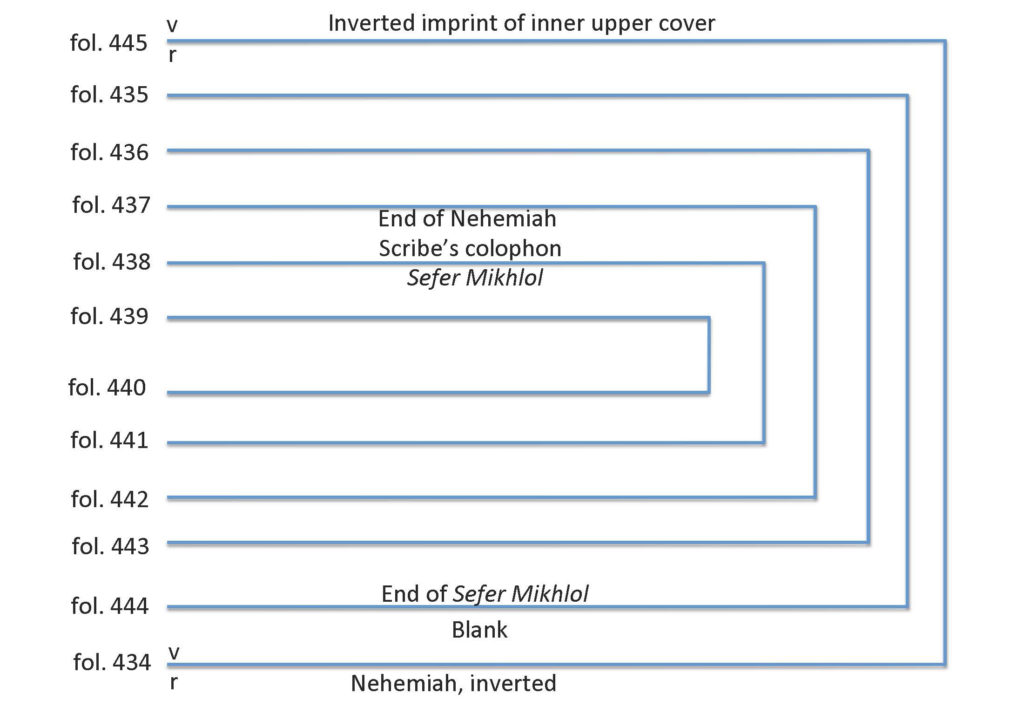

For the most part, the manuscript comprises regular quires of twelve folios; discounting the first two leaves used as a pastedown and flyleaf, there are thirty-nine quires (fig. 1). Exceptions include two gatherings of ten at the end of the Pentateuch (Quires 10 and 11 discussed below) and two gatherings of eight at the beginning and end of the book. In the first gathering of eight, the quire begins with one blank folio, while the remaining fifteen pages contain the first part of the decorated Sefer Mikhlol (1v–8v). In the second instance, the book’s final quire of eight again begins with a blank folio (fol. 446r), followed by the artist’s full-page colophon on fol. 447r; the rest of the quire is mysteriously blank (fig. 2). The preceding gathering, of twelve (Quire 38), contains the last four folios that conclude the Bible with the text of Nehemiah and the scribe’s colophon on fol. 438r. It also includes the second half of Sefer Mikhlol, which begins immediately on fol. 438v and runs for twelve pages; the quire ends with a blank folio (fig. 3). It is apparent that the makers of the book made a structural distinction between the first quire, with the non-biblical Sefer Mikhlol on 8 folios, and the sacred text of the Bible itself, which normally comes on regular quires of 12 folios. The second part of Sefer Mikhlol is in a regular gathering of twelve, but presumably this is because the quire also contains sacred biblical text. The scribe, Moses ibn Zabara, numbered all the quires with Hebrew letters in the lower left-hand corner, except for Quire 11 at the end of the Pentateuch (discussed below), the two that contain Sefer Mikhlol, and the final one, which has Joseph ibn Hayyim’s artistic colophon.[9]

Moses knew what he was doing with the quires: the lengthy scribal colophon specifically mentions that he “comprised it in 37 quires, and a sign for them is ‘if only you had paid attention to my commands, your peace would have been like a river’ [Isaiah 48:18].”[10] In short, while we count thirty-nine actual quires in the manuscript, Moses only considered thirty-seven worth mentioning in the colophon. Which did he leave out for this calculation? There are two possibilities. The first is the very last quire of ten, which contains only the artist’s colophon, plus either of the unnumbered quires with Sefer Mikhlol. The second is that Moses never had the current last quire in mind when he wrote his colophon, so the two missing quires from his count correspond to the two unnumbered quires at the beginning and end of the book—those with Sefer Mikhlol. This seems more plausible and suggests that in both his quire numbering and colophon count, Moses was making a codicological and essentializing distinction between gatherings with the biblical text and those with Sefer Mikhlol.

There is, admittedly, a discrepancy in this counting. On the one hand, Moses seems to have included the penultimate quire in his total colophon count of thirty-seven quires, presumably because it included biblical text. On the other hand, he did not give it a quire number, presumably because, like the first gathering, it contains Sefer Mikhlol, although unlike that first gathering it does contain biblical text. This suggests that while Moses ibn Zabara was sensitive to the structure of his Bible, he could not (or did not) work out a perfect system that would account for all the details in this lengthy and complex book. This sloppiness in the final two quires relative to the rest of the book was noted by Bezalel Narkiss and Aliza Cohen-Mushlin in their painstaking commentary to the Kennicott Bible facsimile; they deemed the presence of so many blank pages at the end of the manuscript a “miscalculation” and a “mystery.”[11]

Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin were certainly correct when they remarked how curious it is that Joseph ibn Hayyim’s artistic colophon was not inserted at the end of the current penultimate quire on fol. 445, on either the blank recto or verso. True, this would not have left a folio free to serve as a pastedown on the cover, but that could have been solved easily with a bifolium, as was done at the beginning of the manuscript. Like many aspects of the Kennicott Bible, Joseph’s colophon has a direct model in the so-called Cervera Bible of ca. 1300 (Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Lisbon, acc. no. MS 72, fol. 449r), where the artist’s colophon was also the last item in the book.[12] Nevertheless, adding a quire of ten and only using this single page is an oddity. Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin suggested that additional text or illustration was originally planned for this final quire, but it is difficult to imagine such a luxurious book being left unfinished in this way. Is it possible that Joseph inserted this additional quire into the book after Moses ibn Zabara finished his scribal work and before it was bound?[13] If so, the current penultimate quire would have been intended to be the final one, and its last blank folio would have served perfectly as the final pastedown, and not, as Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin thought, a waste. At this stage, however, it is prudent to agree with them that the problem of the last gathering—and Joseph’s possible role in the binding of the book—remains a mystery.

The Missing Yud

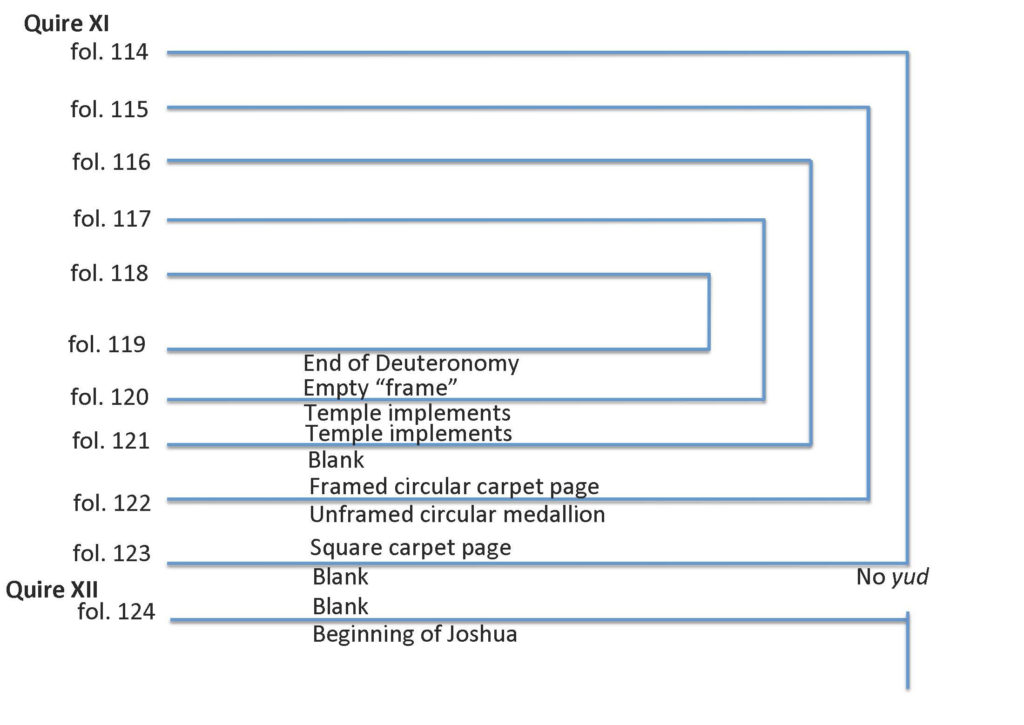

Two other small details point to Moses ibn Zabara’s awareness of quire structures and to the potential for meaning in the practical aspects of a large Bible codex. Among the irregular quires are two gatherings of fourteen (Quires 18 and 19), which seem to have been chosen to complete the section of the Former Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings) within a codicological unit.[14] Similarly, two gatherings of ten were used for Quires 10 and 11, precisely where the Pentateuch ends and a suite of decorative pages begins. The last one evokes the interior of the box binding, in effect “wrapping” the Pentateuch as a single codicological and ideological section within the full Bible as a whole.

Structure of Quire 11

It is precisely at this point, on fol. 123v, that Moses omitted the Hebrew letter yud (corresponding to the number ten in the Hebrew alphabet) for the tenth quire according to his count (fig. 4). There may be several, overlapping reasons why he did so. On a purely aesthetic level, fol. 123v is blank, and Moses may not have wanted to leave a “dangling” quire letter in the lower left-hand corner of an otherwise blank page. On a practical level, he may have reasoned that other markers—the suite of decorated pages followed by an unusual blank page—would be sufficient to signal to the binder that this was the end of the Pentateuch, so the alphanumeric quire indication was superfluous. Yet there also may have been something special about the letter yud itself. In Hebrew, perhaps the most common abbreviation for the name of God is Yud Yud, which is not even pronounced. Leaving out the yud may have been a way to avoid the suggestion that a name of God was being stuck into the corner and used prosaically. Some earlier Iberian Hebrew Bibles likewise omit the yud, which suggests that there was some tradition along these lines, though there are also Bibles with the yud.[15] Whether or not Moses was aware of this tradition, it is certain that he did not follow the model of the Cervera Bible, which like some Iberian Hebrew Bibles used catchwords rather than alphanumeric symbols. Whatever the reason, the missing yud is one more indication that Moses was very thoughtful about the codicological structure of his Bible.

A Christian Owner?

In considering the Kennicott Bible’s quire structure, Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin came to a startling conclusion. The penultimate quire, as we have seen, comprises the last eight pages of Nehemiah (beginning with fol. 434), with the scribal colophon; twelve pages with Sefer Mikhlol; and three blank pages (ending with fol. 445). According to Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin, the final blank page (fol. 445v) contains an upside-down imprint of the colorful vellum pastedown on the inside of the book’s box binding, which must have happened when the page was pressed against it for a long time (fig. 5). “There is no indication of why or when this happened, but one is forced to assume [my emphasis] that it was done by a Christian owner who was not necessarily interested in the Hebrew text of the Bible. He may have . . . detached the penultimate quire, which contains the illuminated, arcaded pages of the Qimhi treatise, and placed them next to the similar pages at the beginning, so that he could see them all together.”[16] This theory is especially seductive because it prioritizes visual aspects of the book: in this scenario, a Christian owner united the two separated parts of Sefer Mikhlol not because he was interested in their text but because he valued the visual harmony of all the arcade pages, which he expected would come at the beginning of the Bible, like Eusebian canon tables. Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin postulated a non-Hebrew-reading owner on the basis of a codicological observation, but they did not explore the broader social implications of this putative Christian owner of the Kennicott Bible.

Conjectural arrangement of Penultimate Quire according to Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin, Kennicott Bible, 31

This turns out to have been a fortunate choice, because these codicological observations do not stand up to scrutiny. First, even if we accept the hypothesis that the penultimate quire was placed at the beginning of the manuscript to produce the upside-down cover imprint on fol. 445v, this would have resulted, as Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin realized, in three folios of Nehemiah at the start of the book (before Sefer Mikhlol) and an upside-down page of Nehemiah from fol. 445v’s conjoint leaf between the two sections of Sefer Mikhlol. Even if a Christian owner was not primarily interested in the Hebrew text, he or she would likely have objected aesthetically to such a discordant arrangement.

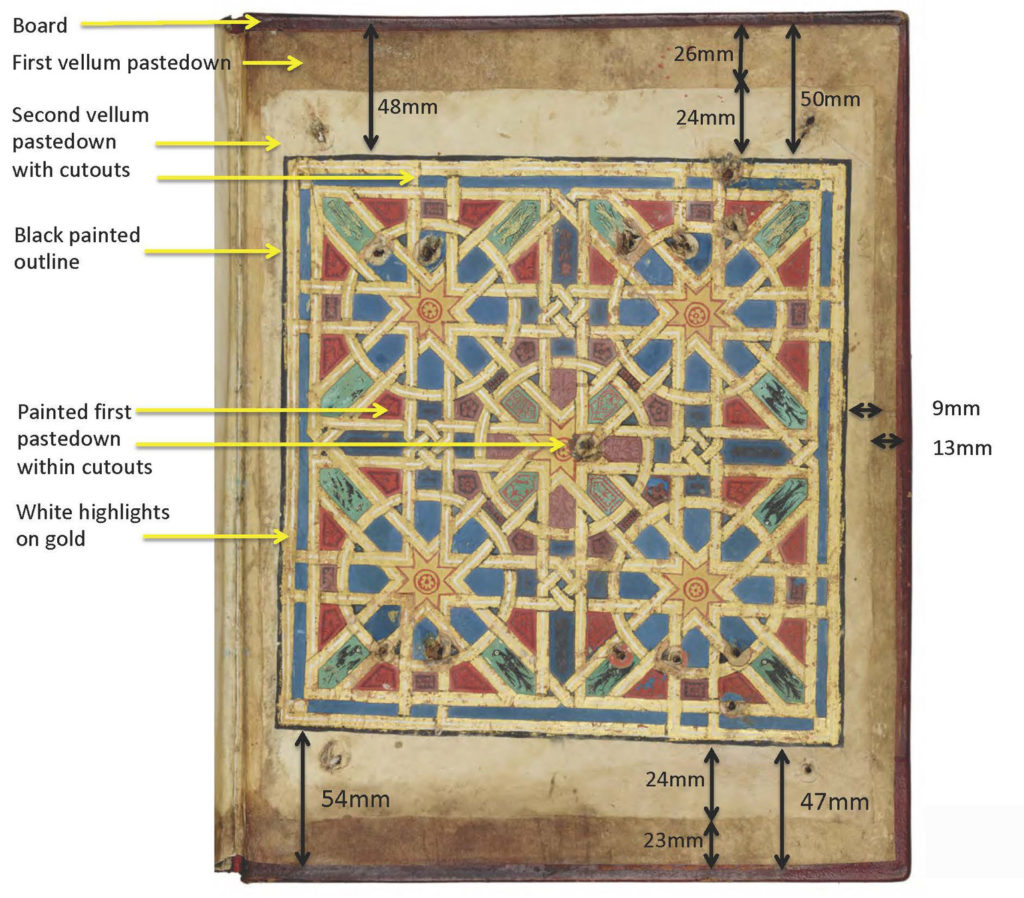

Decorator: Joseph ibn Hayyim and Scribe: Moses ibn Zabara, Front box binding interior, Kennicott Bible, Spain (La Coruña), 1476. University of Oxford, Bodleian Library, acc. no. MS Kennicott 1

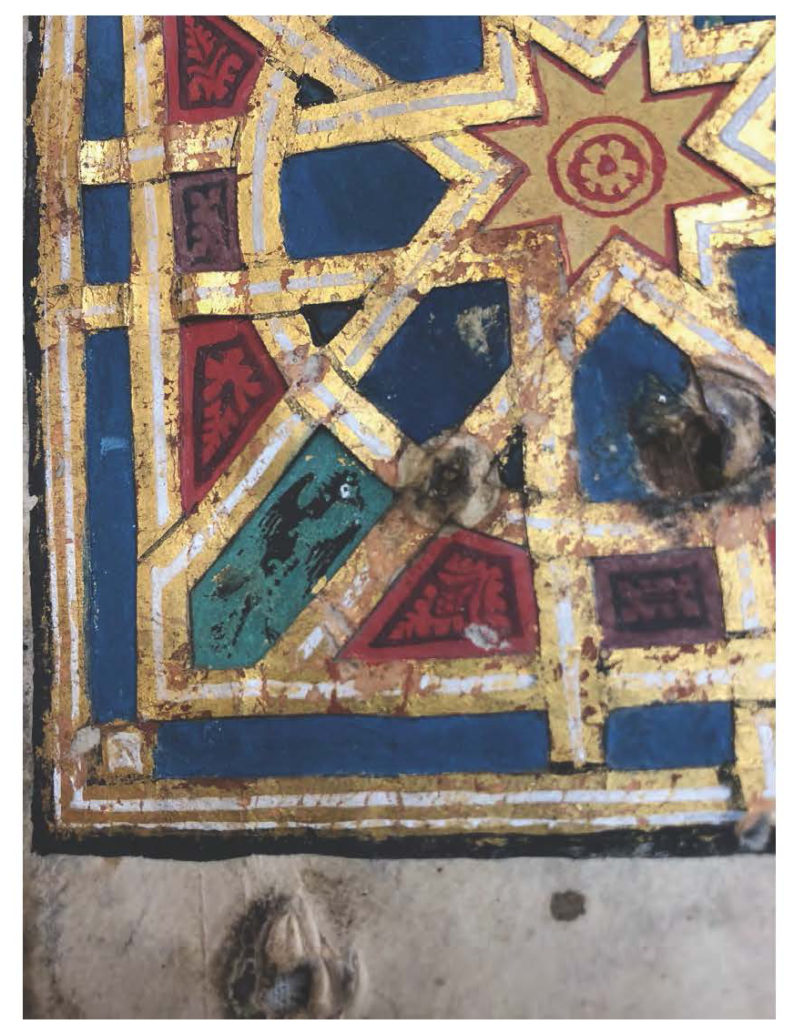

Second, and more important, the observations about fol. 445v are simply wrong. It is true that the cut-out design on the box binding cover could leave imprints: some are visible from folk. 453 to 448, six folios that represent almost the entire final quire (these tactile impressions are not discernible in digital reproductions of the Kennicott Bible but are apparent in situ). From a physical standpoint, if the Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin theory were correct, one would have expected the impressions to be noticeable on more than just fol. 445v, at least on the blank pages (fols. 444v and 445r), but this is not the case. Even if this quire were moved to the front for a short time, just long enough for the cover to imprint itself on a single page, that only makes the original proposition even more puzzling. More problematic—and, indeed, decisive—is that the putative impression on fol. 445v (which was not evident when I examined the manuscript in August 2019) simply could not have been where Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin maintained it was. According to the precise measurements they provided (“27 mm. in the outer margin and 52 and 45 mm. at top and bottom”), and even allowing for some imprecision in those measurements, the purported imprint would have been made by the edge of the decorated rectangle, but in fact, nothing physically distinguishes the edge of the decoration at that point (figs. 6, 7). The interior of the box binding was decorated by cutting out geometric shapes from a piece of vellum, creating negative space, and pasting this onto the first vellum pastedown already on the board; this second, top-layer pastedown (called a doublure in the literature) was painted in gold and highlighted with white paint, and the negative spaces created by the cutouts were painted (on the first pastedown) red, blue, green, and mauve. In other words, the only continuous edge is between the first and second pastedown, not between the pastedown and the decoration. As for the edges created by the cutouts in the design, if the final quire with firm evidence of imprints is any guide, these would have provided ample opportunity for creating impressions, but they are not evident on fol. 445v. In sum, there is no physical evidence to support Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin’s suggestion that the penultimate quire was ever moved to the front of the book, so we can dispense with the tantalizing but unsupportable assumption that there was a Christian owner who manipulated the quires of the Kennicott Bible to make it look more like a Latin book.

Decorator: Joseph ibn Hayyim and Scribe: Moses ibn Zabara, Front box binding interior, lower left corner detail, Kennicott Bible, Bodleian Library, acc. no. MS Kennicott 1

Wrapping the Kennicott Bible

One of the considerations driving the Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin theory was aesthetic: the two clusters of arcades framing Sefer Mikhlol make more sense together at the front of the book rather than split between front and back. If this were a Latin Bible such an arrangement would be more coherent, especially if we think about the formally analogous Eusebian canon tables. But Kennicott was made by a Jewish scribe and artist for a Jewish patron, so it is necessary to consider the logic and meaning behind its intentional structure in other terms.

The history of the Hebrew Bible in Iberia is a rich subject that can only be sketched here;[17] I attend only to features pertinent to the Kennicott Bible. Although the origins of the Iberian Hebrew Bible remain murky, material, scribal, and decorative evidence suggest that such Bibles were based on books made in venerable Jewish centers in the lands now corresponding to Israel, Iraq, and Egypt. These authoritative models traveled across the Islamicate lands of North Africa and into Iberia by the late twelfth century; the earliest decorated copies there can be dated around 1250. Charting the production of Bibles in Catalonia, Aragón, Léon, Castile, and Portugal until the early 1500s is to map in some sense a microcosm of the waxing and waning fortune of different Iberian Jewish communities over three hundred years.[18] The Bibles themselves served several purposes: some were clearly for liturgical use, others for study, and many were “masoretic Bibles” that served to record and transmit an authoritative version of the Bible.[19] The different functions can be determined in part by the different contents and structures, but the categories were not always exclusive: there is no reason masoretic Bibles like Kennicott could not be used for study, and they probably were.

The masoretic Bibles were the most frequently and richly decorated Hebrew Iberian books.[20] They were written as individual volumes composing the major components of the TaNaKh, a Hebrew acronym for Torah (the Pentateuch), Nevi’im (the Former and Latter Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings), or as full pandects (i.e., with all three components). Their most important trait is the presentation of the biblical text with full vocalization, accentuation, and cantillation marks (which indicated how the words should be chanted), none of which were written in the Torah scrolls used liturgically in the synagogue. Even so, the masoretic Bibles tended to conform to the layout of Torah scrolls, which was governed by very precise scribal rules.[21] What most clearly distinguishes the masoretic Bible from the Torah scroll was the codex form and the presence of masoretic texts on the page. The codices also often contain devices that make the books suitable for paraliturgical use, such as markers to indicate the beginning of weekly Torah readings or the additional weekly selections from the Prophets (haftarot).

The Kennicott Bible is typical of the Iberian masoretic Bibles in its page layout, even though its masorah magna is generally not written in a decorative form as is often the case.[22] The presence of non-biblical texts at the beginning and end of the book is also common: among the 135 manuscripts I reviewed, 82 contain some kind of prefatory material (textual, visual, or both), and 61 have texts (usually non-biblical) at the end of the book. These additional items include, among other things, computistical charts, ornamental carpet pages, lists of special Torah passages to be read on holidays, and colophons. By far the most common extra-biblical contents are additional masoretic texts of various kinds, usually lists of grammatical information enclosed in enframing verses or, like canon tables, rendered as shaped columns and/or within arcades.[23] Two representative examples, by way of comparison, are the modestly decorated Bible of Israel ben Casares of 1232 (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, acc. no. Hébreu 25) and the richer Harley Catalan Bible of the fourteenth century (British Library, London, acc no. MS Harley 1528).[24]

What makes the Kennicott Bible unusual is the fact that it does not include the normal masoretic materials before and/or after the biblical text but, rather, David Kimhi’s Sefer Mikhlol. In this respect it stands out as one of a handful of Iberian Bibles that present a slight twist on the customary practices. Most exceptional are the Serugiel Bible (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, acc. no. MS Arch. Selden A. 47) and a TaNaKh split between Cambridge (University Library, acc. no. MS Add. 468) and Cincinnati (Hebrew Union College, Klau Library, acc. no. MS 13), in which the masorah magna is replaced, respectively, by Rashi’s commentary on Genesis and Exodus and Maimonides’s Guide for the Perplexed.[25] More common, albeit still unusual, are nine Bibles that include Kimchi’s grammatical texts. The oldest is a two-volume Castilian Bible from the third quarter of the thirteenth century (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, acc. nos. Hébreu 11 and 12), which has no pre- or postliminary materials and, beginning with the opening of Genesis on fol. 1v, includes Kimhi’s Sefer HaShorashim (Book of Roots) in the margins instead of the masorah magna (this appears in the outer vertical margins, and the masorah parva is in the interior vertical column); toward the end of vol. 2 is Kimhi’s Ayt Sofer (Pen of the Scribe).[26] Two other manuscripts likewise restrict Sefer HaShorashim to the margins of the Bible in place of the masorah magna: British Library, London, acc. no. MS Or. 12325, a Former Prophets fragment of some twenty folios, and another partial Bible with just the Latter Prophets and Writings now in San Lorenzo de El Escorial.[27] It is impossible to say whether there was additional preliminary or postliminary materials in the lost volumes.

In a full TaNaKh dated by its colophon to 1341 (National Library of Israel, Jerusalem, acc. no. MS. Heb. 8°1401), Sefer HaShorashim likewise replaces the masorah magna in the upper and lower margins, but in this case Kimhi’s treatise was not finished by the end of the biblical text, and another 53.5 folios were needed to complete it.[28] Two other fourteenth-century manuscripts also expanded Sefer HaShorashim beyond the biblical core: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, acc. no. MS ebr. 8, and National Library of South Africa, Cape Town, Grey Collection, acc. no. MS 48.b.2.[29] In the Vatican manuscript, the Bible is introduced by a single page containing the beginning of Sefer HaShorashim, which continues in the margins of the Bible ending on fol. 387r; there follow another seventy-eight folios with the remaining text of Sefer HaShorashim. It is unbalanced, but there is nonetheless some sense of wrapping the Bible in the Kimhi text. The Cape Town manuscript does a better job and even enhances the grammatical text by featuring it in decorative arcades at the beginning and end of the Bible.

A final group comprises three manuscripts that maintain the traditional masorah in the body of the Bible and place the grammatical works at the beginning and end. The earliest of these from ca. 1300 is the Cervera Bible (Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Lisbon, acc. no. IL. 72), which opens on fols. 1v–6v with a series of short, anonymous grammatical and masoretic texts in richly decorated arcades and closes with Kimhi’s Ayt Sofer on fols. 434v–448v, also in inventive arcades and painted frames.[30] A mid-fourteenth-century exemplar in the Karaite Synagogue in Cairo, a manuscript known to scholars as Gottheil 16 (Karaite Synagogue of Cairo, acc. no. Ms. 16), has twelve pages of Sefer Mikhlol in frames at the beginning of the book, two more pages after the Pentateuch, and another two after Prophets (these major divisions of the TaNaKh are typically demarcated in some way); it closes with nineteen more framed Sefer Mikhlol pages and four concluding pages of masoretic notes.[31] Finally, there is the Kennicott Bible, which opens and closes with Sefer Mikhlol. The most immediate conclusion from this review is that only 2 out of 135 Iberian Bibles contain Sefer Mikhlol, and while the Cervera Bible provided a formal model for Kennicott, Moses ibn Zabara replaced its preliminary and postliminary texts, turning not to the usual Kimhi Sefer HaShorashim but to the exceptional Sefer Mikhlol.

The manuscripts with David Kimhi’s texts deserve more attention as a group, but certain points emerge with regard to the Kennicott Bible. Like more than half of the Iberian Bibles I surveyed, it wraps the biblical text—both before and after as well as top and bottom—in masoretic material. At the same time, it is among a small group that does so specifically with texts by Kimhi, and it is almost unique among surviving examples in using Sefer Mikhlol. This is not the place for extended remarks on the history of Hebrew grammatical treatises in Iberia and the differences among Kimhi’s writings,[32] but in general, the masorah and the works of Kimhi served a complementary purpose: to provide a lexical-grammatical apparatus to ensure the accuracy of the sacred text of the Bible and to crystallize the grammatical bases for understanding it properly. Unlike the traditional masorah, Sefer Mikhlol was not explicitly about the Torah text per se, but the sacred Torah text was itself the bedrock of Hebrew grammar. And the point of Sefer Mikhlol was, as Kimhi explained, to restore the sacred tongue to Jews in exile and to provide the grammatical foundation for studying Torah, Talmud, and their commentaries. He wrote: “If your knowledge of Torah be thorough, But no interest in grammar you’ve showed, Then you’ve guided your ox through the furrow, With nary a whip nor a goad.”[33]

Sefer HaShorashim was essentially a dictionary and in that sense was a logical replacement for the pithy masorah that usually accompanied Iberian Bibles. Sefer Mikhlol, by contrast, was, as Frank Talmage succinctly characterized it, a summa—a comprehensive synthesis—of all Hebrew grammar. In designing the Kennicott Bible, Moses ibn Zabara and Joseph ibn Hayyim were guided by the Cervera Bible and certainly appreciated the traditional structural principle of wrapping the biblical text. But unlike the Cervera Bible and such books as Vat.ebr.8, Moses retained the traditional masorah in the body of the Bible and also wrapped it in the most complete Hebrew grammatical work, which by the late fifteenth century had become independently canonical (e.g., British Library, London, acc. no. Or. 1045). Doing so was part of the overall conception of the Kennicott Bible, whose material splendor also made it a kind of summa of Iberian Hebrew Bibles, a perfect expression of God’s sacred text with the apparatus necessary to comprehend it fully.

No less than the textual components, the visual scheme of the Kennicott Bible was meant to guide the user’s experience, to present him with a sumptuous and deeply meaningful book; the masorah, for example, could be considered a “fence” protecting the sacred text while the decorative pages demarcated divisions of the TaNaKh in specific ways.[34] As such, it was fully in keeping with other Iberian Hebrew Bibles whose scribes, masoretes, painters, and users—sometimes one and the same—manipulated the decorated codex format to express their faith and knowledge, talent and limitations, status and place both within the Jewish community and in the Gentile world beyond.[35] Indeed, as the example of the Bohemian Bible in the Walters shows, providing preliminary texts and images was common among Christians in the Middle Ages. There were also instances of individual books being “wrapped” in textiles (one thinks, for instance, of Ottonian Gospel books).[36] The Kennicott Bible visually synthesized two traditions. The columnar texts and framing devices, as well as some of the figural iconography around the pre- and postliminary Sefer Mikhlol, shared characteristics with Christian Bibles, whereas the decorative vocabulary was rooted in the visual language of Islamicate art.[37]

Yet as much as the Kennicott Bible shared features with Islamic and Christian works, it was a distinctively Jewish book. The arcades were particularly meaningful in terms of the Sefer Mikhlol’s contents: Kimhi divided the text into three parts that he called “gates”—the gate of verb grammar (sha’ar dikduk ha-poalim), the gate of noun grammar (sha’ar dikduk ha-sheimot), and the gate of particle grammar (sha’ar dikduk ha-milim).[38] The Hebrew Bible itself had been analogized to the Temple, and architectural motifs were used to adorn many Bibles in Islamicate lands.[39] In the Kennicott Bible, this has been applied specifically to the Sefer Mikhlol, instantiating the idea that grammar is a gateway leading into the truth of the Bible’s words contained within. As we have seen, Moses ibn Zabara and Joseph ibn Hayyim were sensitive to the formal structure of the book, distinguishing Sefer Mikhlol from the Bible and the different parts of the TaNaKh from one another in meaningful ways. Its extensive visual apparatus certainly enhanced the status of the book for its recipient, Isaac, son of Solomon of Braga, and helped him use it. But as Moses ibn Zabara’s colophon implored Isaac, quoting Joshua 1:8, “let not this book of Torah cease from your lips, and meditate on it day and night, so that you are careful to do everything written in it, etc.” The emphasis on the lips suggests that ultimately it is the words of the Bible that were most important, and as valuable as Kennicott’s codicology and decoration were, it was the words of Sefer Mikhlol and the masorah on the biblical pages that simultaneously protected and revealed the sacred text.

Postscript

The Kennicott Bible was completed only sixteen years before the cataclysmic expulsion of the Jews from Spain. One wonders about the fates of Moses ibn Zabara, Joseph ibn Hayyim, and Isaac, son of Don Solomon. One wonders about the fates of Moses ibn Zabara, Joseph ibn Hayyim, and Isaac, son of Don Solomon. The Bible obviously survived, but little is known about its subsequent history before it entered the Oxford collections in 1771.[40] Not all books were so lucky, as the many partial Hebrew Iberian Bibles attest, but this was not solely an Iberian experience. A copy of Aesop’s Fables printed in 1495 by Bernardinus de Misintis of Brescia, now in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (acc. no. 91.12), used cut-up pages from a Talmud manuscript of ca. 1200 for its covers and flyleaves.[41] To be sure, the heavy parchment of many Christian manuscripts—superseded antiphonals, for example—was used as binding material in later books, but the Walters fragments, which almost certainly were not given up freely by their original owners, represent a poignant twist on the phenomenon of wrapping that was so important to the structure and meaning of the Kennicott and other Hebrew Bibles.

I am grateful to Sonja Drimmer, Lynley Herbert, and Ben Tilghman for the opportunity to participate in the Baltimore workshop on codicology that they organized in October 2019. Profound thanks are due to César Merchán-Hamann, director of the Bodleian Library’s Leopold Muller Memorial Library and curator of Hebraica and Judaica at the Bodleian, for permitting Linda Safran and me to study the Kennicott Bible in August 2019. I also thank Rahel Fronda of the Bodleian for insightful conversations about Hebrew bible manuscript. In addition to co-authoring an earlier article on the Bible, Linda Safran helped prepare the current essay for publication; her work has improved it immeasurably, but any errors are solely mine.

[1] According to the Abstract for W.805: “The illumination of the Creation within a cosmographic scheme is based in part on the woodcut illustrations of the Creation in the 1483 Koberger Bible and the 1493 Nuremberg chronicle by the same printer.” https://manuscripts.thewalters.org/viewer.php?id=W.805#page/1/mode/2up

[2] See, in general, Matthew R. Crawford, The Eusebian Canon Tables: Ordering Textual Knowledge in Late Antiquity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019); and, for a more focused discussion, Beatrice Kitzinger, “Framing the Gospels, c.1000: Iconicity, Textuality, and Knowledge,” in Marcia Kupfer, Adam S. Cohen, and J. H. Chajes, eds., The Visualization of Knowledge in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (Turnhout: Brepols, 2020), 87–114.

[3] The entire manuscript is available online at https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/8c264b23-f6cc-4f18-98cf-9d75f7175b54/.

[4] For a translation of the full colophon, see Adam S. Cohen and Linda Safran, “Abstraction in the Kennicott Bible,” in Elina Gertsman, ed., Abstraction and Medieval Art: Beyond the Ornament (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021), 89–114, esp. n. 4.

[5] See, in general, Maria Teresa Ortega Monasterio, “Sephardic Hebrew Bibles of the Kennicott Collection,” BABELAO5 (2016): 127–68; and Ortega Monasterio, “Some Hebrew Bibles in the Bodleian Library: The Kennicott Collection,” Journal of Semitic Studies 62 (2017): 93–111, esp. 96–100 with a good description of the manuscript.

[6] There are 453 numbered folios plus six additional ones (marked as, e.g., fol. 143a), for a total of 459. For a thorough description of the manuscript, see Bezalel Narkiss, Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts in the British Isles: Catalogue Raisonné 1. The Spanish and Portuguese Manuscripts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982), 153–59. Narkiss, followed by Ortega Monasterio, “Some Hebrew Bibles,” count 461 folios by including the pastedown in the front cover and the conjoint first flyleaf. They also count this bifolium as a quire. My count differs, and the implications will be explained below.

[7] For concise treatments, see Elvira Martín-Contreras, “Masora and Masoretic Interpretation,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Biblical Interpretation, ed. Steven L. McKenzie (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 1:542–50; and Kay Joe Petzold and Hanna Liss, “Masorah, Masoretes,” in Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception, ed. Christine Helmer et al. (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2019), 17:1267–80.

[8] In addition to the Bodleian website, see also the extensive facsimile commentary by Bezalel Narkiss and Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, The Kennicott Bible, 2 vols. (London: Facsimile Editions, 1985), as well as Cohen and Safran, “Abstraction.”

[9] On the methods that Hebrew scribes used for indicating quires, which was done to ensure that they were ordered correctly during the binding process, see Malachi Beit-Arie, “Les procédés qui garantissent l’ordre des cahier, des bifeuillets et des feuillets dans les codices hébreux,” in Philippe Hoffmann, ed., Recherches de la codicologie comparée. La composition du codex au Moyen Âge, en Orient et en Occident (Paris: Presses de l’Ecole normale supérieure, 1998), 137–51. Like their Christian counterparts, Hebrew scribes primarily used numbers or “catchwords” (the next word to appear at the beginning of the subsequent quire).

[10] Moses employed a common Hebrew linguistic-numerical device, based on the fact that every Hebrew letter has a numerical value (e.g., aleph is 1, bet is 2, vav is 6, nun is 50, and so on). To denote 37, he found a word corresponding to that number, “לוא” (lamed, vav, aleph), which is the first word in Isaiah 48:18, a verse that Moses wrote out in its entirety.

[11] Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin, Kennicott Bible, 2:29–31.

[12] On the Cervera Bible and the relationship of the two manuscripts, see ibid; and Katrin Kogman-Appel, Jewish Book Art between Islam and Christianity: The Decoration of Hebrew Bibles in Medieval Spain (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 98–130 and 212–13.

[13] Some support for this scenario might be found in the wording of Joseph’s colophon, “I, Joseph ibn Hayyim painted and completed this book”—i.e., he was responsible for seeing it through the binding process and would have been in a position to add this quire at the end. Joseph may simply have been copying the same wording in the Cervera Bible, so it would be unwise to put too much weight on this. For a review of the literature on the Cervera Bible’s colophon and a new interpretation, see Julie A. Harris, “Deliberate Imperfection in Medieval Hebrew Manuscripts from Iberia,” Ars Judaica17 (2021): 1–23. I thank her for sharing her stimulating work with me prior to its publication.

[14] When Moses got to the end of Quire 17 (fol. 193) he must have had a sense that about 26 folios were needed to complete the Former Prophets (fol. 219r). Had he continued with regular quires of 12, he would have ended up with gatherings of 12, 12, and 2, which was clearly unacceptable. Alternatively, three slightly reduced gatherings of 10 would have taken him to fol. 223, well beyond what was needed to conclude the section of the Former Prophets. Choosing two gatherings of 14 seems to have been the preferred choice because it was “balanced” and only a little past what was needed.

[15] I have not systematically checked every Hebrew Iberian Bible, but examples without the yud include Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), Paris, acc. no. Hébreu 14 of ca. 1200 and the Perpignan Bible of 1299 (BnF;acc. nos. Hébreu 7). For descriptions, see Javier del Barco, Manuscrits en caractères hébreux conservés dans les bibliothèques de France, 4. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Hébreu 1 a 32: Manuscrits de la bible hébraïque (Turnhout: Brepols, 2011), 46–51 and 76–78. Manuscripts with the yud include the Harley Catalan Bible of the mid-fourteenth century (British Library, London, acc. no. MS Harley 1528), and the Duke of Sussex’s Catalan Bible from the third quarter of the fourteenth century (British Library, London, acc. no. MS Add. 15250). For descriptions of both manuscripts, see Narkiss, Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts in the British Isles, 105–9. This line of inquiry deserves further consideration.

[16] Narkiss and Cohen-Mushlin, Kennicott Bible, 2:30–31.

[17] In addition to items cited above, for general treatments see, most recently, Esperanza Alfonso et al., eds., Biblias de Sefarad (Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España, 2012); David Stern, The Jewish Bible: A Material History (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017), esp. 90–105; and Norman Roth, The Bible and Jews in Medieval Spain(Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2021). Also important are two essays by Sarit Shalev-Eyni: “Tradition in Transition: Mudejar Art and the Emergence of the Illuminated Sephardic Bible in Christian Toledo,” Medieval Encounters 23 (2017): 531–59; and “From Castile to Lisbon: The Sephardic Biblical Codex and Mudejar Visual Culture, Mid-Thirteenth to Late Fifteenth Centuries,” in Luís Afonso and Tiago Moita, eds., Sephardic Book Art of the Fifteenth Century (London: Harvey Miller, 2019), 37–58.

[18] See esp. Kogman-Appel, Jewish Book Art.

[19] David Stern, “The Hebrew Bible in Europe in the Middle Ages: A Preliminary Typology,” Jewish Studies: An Internet Journal 11 (2012): 235–322; http://www.biu.ac.il/JS/JSIJ/11-2012/Stern.pdf. Stern’s typology has been widely accepted.

[20] I cannot pretend to have identified and considered every extant example, but I base the following comments on information about 135 Iberian Hebrew Bibles gathered from scholarly literature, published catalogues, and online library collections. The following repositories deserve special mention: the National Library of Israel (and its Ktiv Project, supported by the Friedberg Jewish Manuscript Society), the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the British Library, and the Bodleian Library (supported by the Polonsky Foundation Digitization Project).

[21] See, for example, Javier del Barco, “Shirat ha-Yam and Page Layout in Late Medieval Sephardic Bibles,” in Afonso and Moita, Sephardic Book Art, 107–20.

[22] On both decorative and figurative masorah, see, e.g., Dalia-Ruth Halperin, Illuminating in Micrography: The Catalan Micrography Mahzor; MS Heb 8°6527 in the National Library of Israel (Leiden, 2013); Halperin, “Decorated Masorah on the Openings Between Quires in Masoretic Bible Manuscripts,” Journal of Jewish Studies 65 (2014): 323–48; and Elvira Martín-Contreras, “The Image at the Service of the Text: Figured Masorah in the Biblical Hebrew Manuscript BH Mss1,” Sefarad 76 (2016): 55–74, all with earlier literature.

[23] For the phenomenon of the framing verses, see, most recently, Dalia-Ruth Halperin, “Clockwise–Counterclockwise: Calligraphic Frames in Sephardic Hebrew Bibles and Their Roots in Mediterranean Culture,” Manuscript Studies 4 (2019): 231–69; and Julie A. Harris, “The Iberian Hebrew Bible: Rabbinic Writings and Ornamental Carpet Pages,” Gesta 60 (2021): 1–19.

[24] On these manuscripts, see, in addition to the online catalogues, del Barco, Manuscrits en caractères hébreux, 156–63; and Narkiss, Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts in the British Isles, 107–9.

[25] For descriptions of the Serugiel Bible, completed in Soria in 1304, and the Cambridge manuscript (the “Cambridge Illustrated Small Bible”) from the last quarter of the fifteenth century, see Narkiss, Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts in the British Isles, 36–38 and 161–62, who seems not to have been aware of the Cincinnati companion volume. The unusual pairing of Rashi’s commentary and especially Maimonides’s Guide with the Bible deserves further exploration.

[26] On Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, acc. nos. Hébreu 11–12, perhaps made in Burgos, see del Barco, Manuscrits en caractères hébreux, 62–67 (these two manuscripts were originally one volume). There are two codicological items of interest in this Bible. First, the Ayt Sofer treatise begins on fol. 230r, which is the last page of Nehemiah; it might have been more logical to begin Ayt Sofer on the verso along with the beginning of Chronicles, a division often visually marked in Iberian Bibles. Apparently it was deemed preferable not to have empty margins on fol. 230r. Second, sometime in the last quarter of the fifteenth century, a gathering of eight folios was inserted between the Pentateuch and Joshua (who begins the Former Prophets); this contains a list, based on Maimonides, of positive and negative commandments found in the Torah. The text is written in three shaped columns in an architectural framework.

[27] I have found no scholarly work on the London manuscript. For a description of the Escorial Bible (acc. no. MS G-I-12), see Francisco Javier del Barco del Barco, Catálogo de manuscritos hebreos de la comunidad de Madrid (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Instituto de Filología, 2003), 1:147–48. The manuscript is also included in Alfonso et al., Biblias de Sefarad, 224–27, where certain codicological and layout idiosyncrasies are discussed.

[28] Although this manuscript, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem, acc. no. MS Heb. 8o1401, is fully online, I have not found more than passing references to it in the scholarly literature. See, e.g., María Teresa Ortega Monasterio, “Apéndices masoréticos en manuscritos bíblicos españoles,” Sefarad 68 (2008): 343–68, who remarks briefly (366) on the phenomenon of Kimhi’s text replacing the masorah.

[29] On the first, see Benjamin Richler, ed., Hebrew Manuscripts in the Vatican Library: Catalogue (Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 2008), 5. The Cape Town manuscript has not been thoroughly catalogued; see the entry in Carol Steyn, ed., The Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the Grey Collection of the National Library of South Africa, Cape Town, 1: Manuscripts 2.a.16–3.c.25 (Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik, Universität Salzburg, 2002), 191–93 (plate 166, with a color reproduction of fol. 1r, is printed upside down). Because of the limited description of the manuscript, it is not possible to be more precise here about the Bible’s structure.

[30] The Kimhi pages are situated between the scribe’s and artist’s colophons on fols. 434r and 449r, an arrangement followed in the Kennicott Bible.

[31] Because of its location, this manuscript is little known, and I have not seen any pages of it reproduced. My description is based on the brief descriptions in the Ktiv online catalogue of the National Library of Israel and the classic article by Richard Gottheil, “Some Hebrew Manuscripts in Cairo,” Jewish Quarterly Review 17 (1905): 609–55, no. 16 (where he noted the similar placement of Sefer Mikhlol in Vat.ebr.8 and the Kennicott Bible). The fullest treatment is Kogman-Appel, Jewish Book Art, 166–68; she conjectured that the Bible was made in Castile. For a recent general review of the Karaite manuscripts in Cairo, see Yoram Meital, “A Thousand-Year-Old Biblical Manuscript Rediscovered in Cairo: The Future of the Egyptian Jewish Past,” Jewish Quarterly Review 110 (2020): 194–219.

[32] The subject is quite extensive. See, briefly, Mordechai Cohen, “David Qimhi (Radak),” in Magne Sæbø, ed., Hebrew Bible Old Testament, the History of Its Interpretation: The Middle Ages (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2000), 388–415; and Judith Kogel, “Le‘azim in David Kimhi’s Sefer ha-shorashim: Scribes and Printers through Space and Time,” in Javier del Barco, ed., The Late Medieval Hebrew Book in the Western Mediterranean: Hebrew Manuscripts and Incunabula in Context (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 182–200; and Judith Kogel, “Qimḥi’s Sefer ha-Shorashim: A Didactic Tool,” Sefarad 76 (2016): 231–50.

[33] Quoted and translated by Frank Ephraim Talmage, David Kimhi: The Man and the Commentaries (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975), 94; Sefer Mikhlol is discussed on 54–70 and 83–115. Talmage situates Kimhi’s treatises not only in the history of Hebrew grammatical works but also in the context of competing approaches to biblical interpretation (e.g., peshat and drash). For an introduction to the subject, see two important works of Mordechai Z. Cohen: Three Approaches to Biblical Metaphor: From Abraham Ibn Ezra and Maimonides to David Kimhi (Leiden, 2003); and The Rule of Peshat: Jewish Constructions of the Plain Sense of Scripture and Their Christian and Muslim Contexts, 900–1270 (Philadelphia, 2020).

[34] David Stern, “The First Jewish Books and the Early History of Jewish Reading,” Jewish Quarterly Review 98:2 (2008): 163–202, esp. 189–94; Annette Weber, “‘The Masoret Is a Fence to the Torah’: Monumental Letters and Micrography in Medieval Ashkenazic Bibles,” Ars Judaica 11 (2015): 7–30; Cohen and Safran, “Abstraction.”

[35] See the exemplary studies by Eva Frojmovic, “The Patron as Scribe and the Performance of Piety in Perpignan during the Kingdom of Majorca,” in Esperanza Alfonso and Jonathan Decter, eds., Patronage, Production, and Transmission of Texts in Medieval and Early Modern Jewish Cultures (Turnhout: Brepols, 2014), 299–337; Eva Frojmovic, “Inscribing Piety in Late-Thirteenth-Century Perpignan,” in del Barco, Late Medieval Hebrew Book, 107–47; Katrin Kogman-Appel, “The Scholarly Interests of a Scribe and Mapmaker in Fourteenth-Century Majorca: Elisha ben Abraham Bevenisti Cresques’s Bookcase,” in del Barco, Late Medieval Hebrew Book, 148–81 (which includes some comments on the use of Kimhi in the Farhi Bible); and Katrin Kogman-Appel, “Calligraphy and Decoration in the Farhi Codex (Sassoon coll. Ms 368, Mallorca, 1366–83),” in Afonso and Moita, Sephardic Book Art, 13–35.

[36] Anna Bücheler, Ornament as Argument: Textile Pages and Textile Metaphors in Medieval Manuscripts (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2019).

[37] For a review of Kennicott, see Cohen and Safran, “Abstraction,” 101–3 (appendix). For the much broader (and contentious) issue of the relationship between Jewish and Islamic art, see, among others, Kogman-Appel, Jewish Book Art; Eva Frojmovic, “Jewish Mudejarismo and the Invention of Tradition,” in Carmen Caballero-Navas and Esperanza Alfonso, eds., Late Medieval Jewish Identities: Iberia and Beyond (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 233–58; and the recent studies of Shalev-Eyni cited above. An important and overlooked contribution is Vivian B. Mann, “A Shared Tradition: The Decorated Pages of Medieval Bibles and Qur’ans,” in Stephen Pickett, ed., The Edinburgh Companion to the Bible and the Arts (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), 161–74.

[38] For an edition of the text, see David Kimhi, Sefer Mikhlol, ed. Isaac Rittenberg (Lyck, Poland: Fettsel, 1862; repr. Jerusalem, 1966). In the Kennicott Bible, the prefatory text that enumerates the three gates is toward the beginning of fol. 1v.

[39] Rachel Milstein, “Hebrew Book Illumination in the Fatimid Era,” in Marianne Barracund, ed., L’Égypte fatimide: Son art et son histoire. Actes du colloque organisé à Paris les 28, 29 et 30 mai 1998 (Paris: Presses de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 1999), 429–40; repr. in Eva Hoffman, ed., Late Antique and Medieval Art of the Mediterranean World(Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007), 229–41. See also Harris, “Iberian Hebrew Bible.”

[40] Like other books, this Bible was brought to North Africa; it was acquired in Gibraltar around 1760 before being purchased by the Bodleian at the recommendation of Benjamin Kennicott. For a detailed account, see the forthcoming publication by Noam Sienna, Jewish Book Culture in Early Modern North Africa. I am grateful to Dr. Sienna for his guidance on this point.

[41] The fragments are from pages 18a, 19b, and 20a of Tractate Gittin and pages 6a/8b from Tractate Sotah.