Giuseppe Arcimboldo (Italian, 1527–1593), Rudolf II of Habsburg as Vertumnus, 1590, oil on panel. 27 1/2 × 22 13/16 (70 × 58 cm). Skokloster Castle, acc. no. SKO 11615

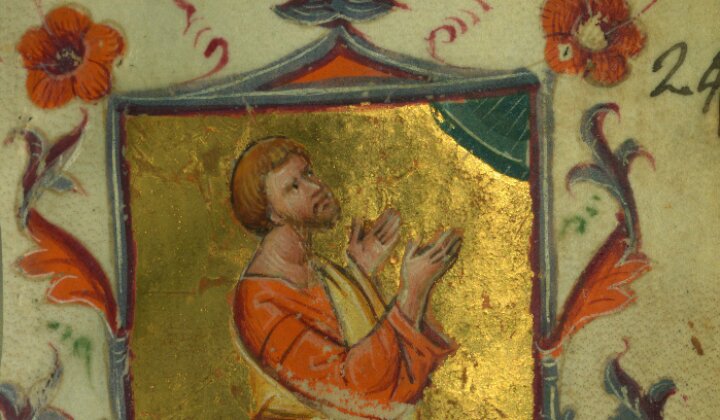

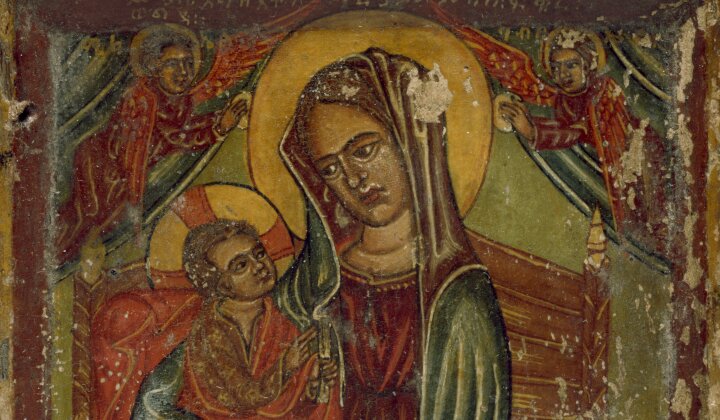

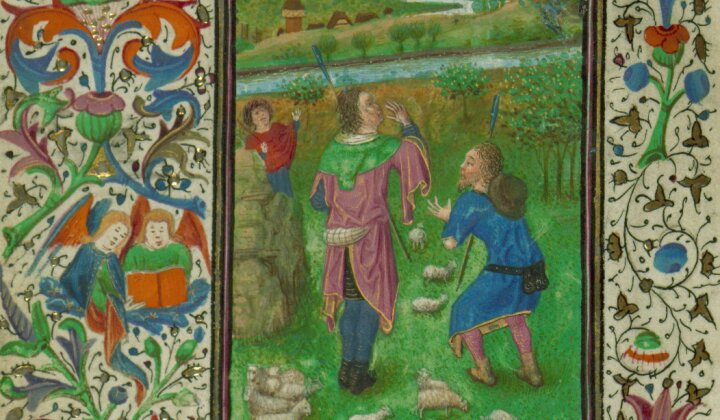

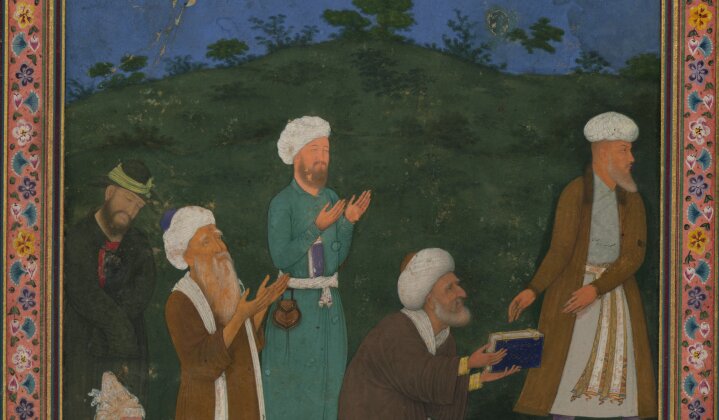

Invention, ingenuity, and curiosity are resonant terms in science and art as much today as in the Renaissance; indeed, they are often seen as characteristic of new intellectual ideals that emerged in the period from the Renaissance through the so-called scientific revolution. This essay considers these ideals in relation to the making of works of art and to the development of art theory in the early modern period. Perceptive and penetrating insights into these topics are to be found in Joaneath Spicer’s many publications.[1] Take, for example, the first of these terms, invention. Spicer laid out what she called a suggestive hypothesis about the “different roles played by the critical notion of ‘invention’ in the creative endeavors of [Emperor Rudolf II’s] court artists, on the one hand, and scientists, on the other.”[2] A common view of modern science sees it as characterized by discoveries and inventions, as it accumulates ever more accurate and useful representations of nature. But, as Spicer points out, there is a great difference between Renaissance and modern invention: where modern invention presupposes the generation of new knowledge, improvement, and progress, Renaissance invenire meant literally to “come upon” or find something, only after, according to Spicer’s formulation, the discoverer “grasp[ed] its significance through the application of intellect and learning.”[3] Examining court mathematicians and astronomers Tycho Brahe (1547‒1601) and Johannes Kepler (1571‒1630), and court artists Giuseppe Arcimboldo (ca. 1527‒1593), Joris Hoefnagel (1542‒1601), and Roelandt Savery (1576‒1639),[4] Spicer lays out a range of meanings that invenire and inventio could have had in the sixteenth century. She reviews the appreciation of Arcimboldo’s 1590 allegorical portrait of Emperor Rudolf II as the Roman God Vertumnus (fig. 1) as an “invenzione in the guise of a cleverly devised, light-hearted capriccio,” while other “inventions” of the same period took the guise of innovations or useful materials or techniques.[5]

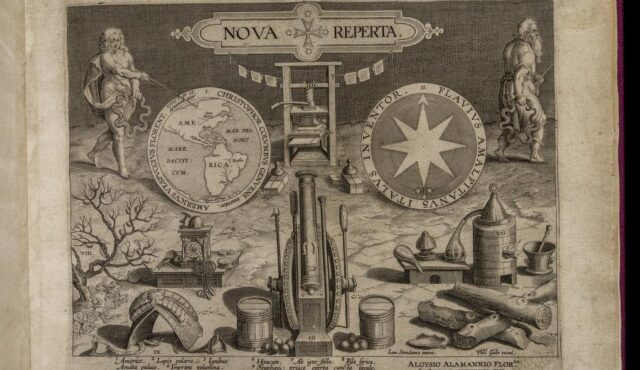

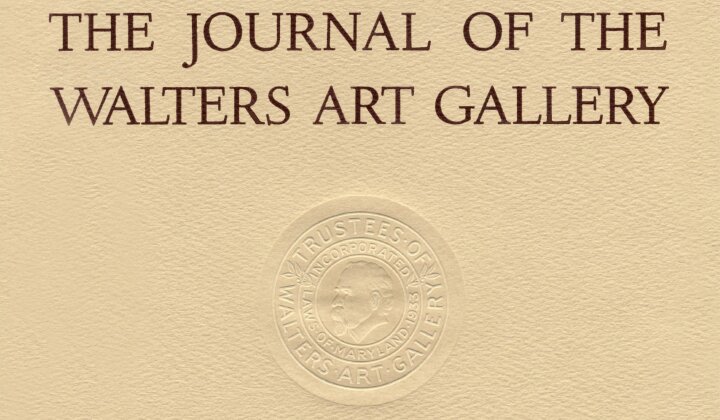

Philips Galle after Stradanus (Jan van der Straet, Flemish, 1523–1603), Color olivi (Oil painting), Nova Reperta, ca. 1588, engraving. Newberry Library, Chicago, acc. no. W 2182, plate 15, digitized on archive.org. Caption: Colorem olivi commodum pictoribus, invenit insignis magister Eyckius (The famous Master Eyckius discovered oil as a convenience for painters)

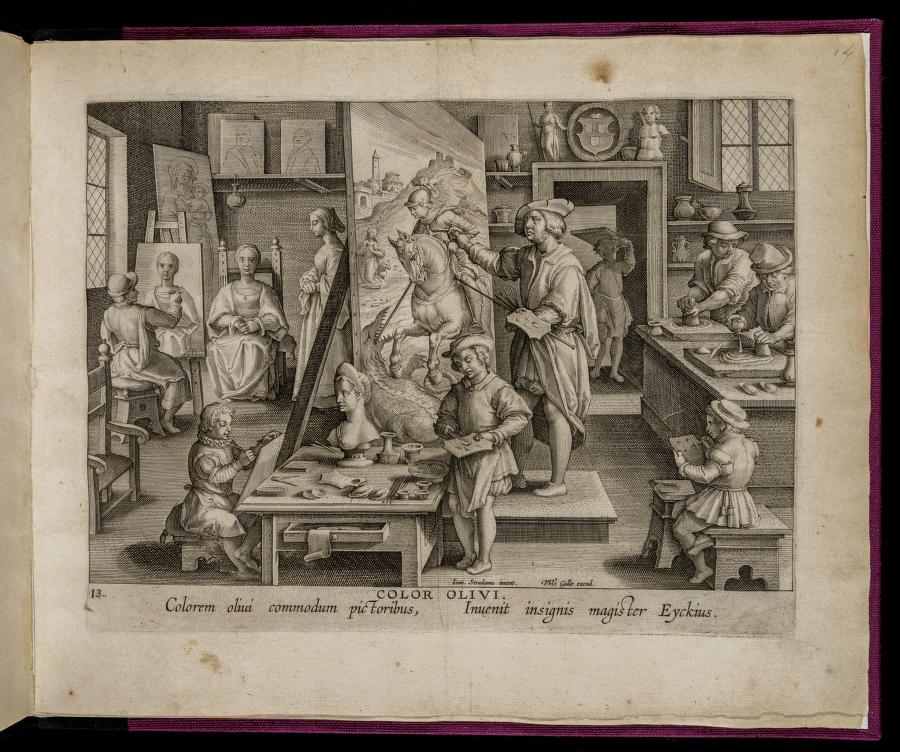

The polymathic artist at the Medici court, Jan Stradanus (1523‒1605) calls Jan van Eyck’s (1390‒1441) use of oil paint an “invention” (fig. 2).[6] Stradanus named eyeglasses as another “invention” (fig. 3), which accords with Spicer’s view that invention in the visual arts could mean a clever design, a result of the imagination, but did not necessarily imply improvement or progress, except in the case of new materials or techniques. In contrast, the astronomer Brahe itemized and described the instruments he used, noting whether they were his own invention or not. As Spicer concludes, “None of his inventions are totally new but all imply progress.”[7] Spicer views the differences between the inventions of artists like Arcimboldo and Stradanus and scientists like Brahe as falling along a “continuum between the poles of present pleasure and progressive utility.”[8] In her account, Galileo Galilei (1564‒1642) and Kepler’s correspondence in 1609‒1610 about Galileo’s discoveries of new celestial phenomena with the telescope are a pivot point in “the genuine paradigm shift in the attitudes towards the notion of invention . . . away from the clever secret towards the vehicle for universal progress and the nascent scientific revolution.”[9]

Conspicilla (Eyeglasses), Nova Reperta, plate 16. Caption: Inventa conspicilla sunt, quae luminum obscuriores detegunt caligines (Also invented were eyeglasses which dispel dark veils from the eyes)

Mechanical Matters

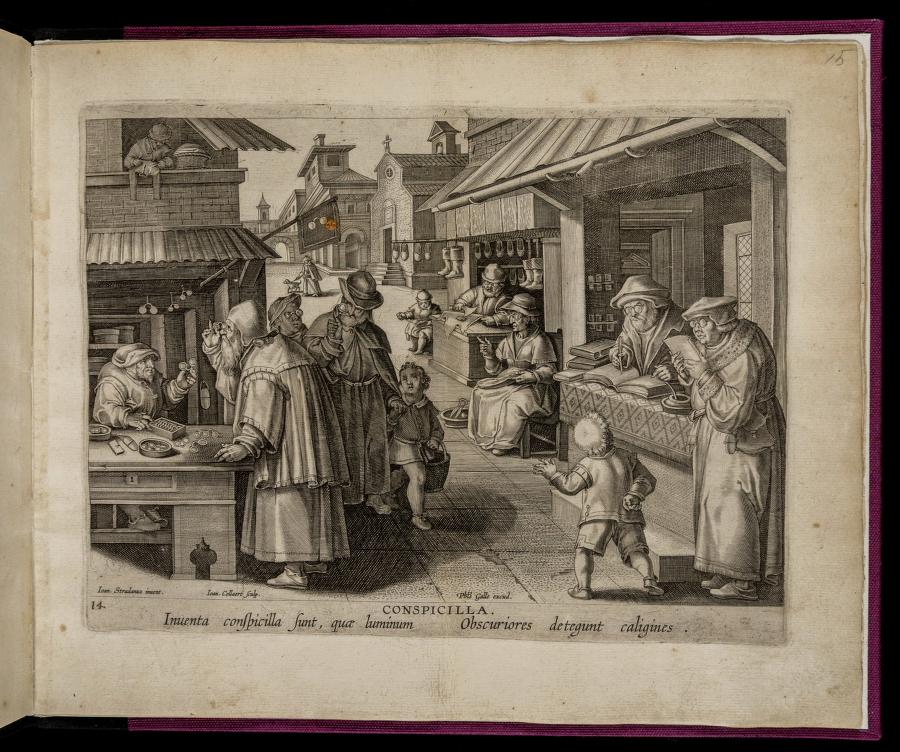

Title Plate, Nova Reperta. Caption: (I) America, (II) Magnetic Compass, (III) Gunpowder, (IV) Printing Press, (V) Iron Mechanical Clock, (VI) Guaiacum, (VII) Distillation, (VIII) Silkworm, (IX) Stirrup

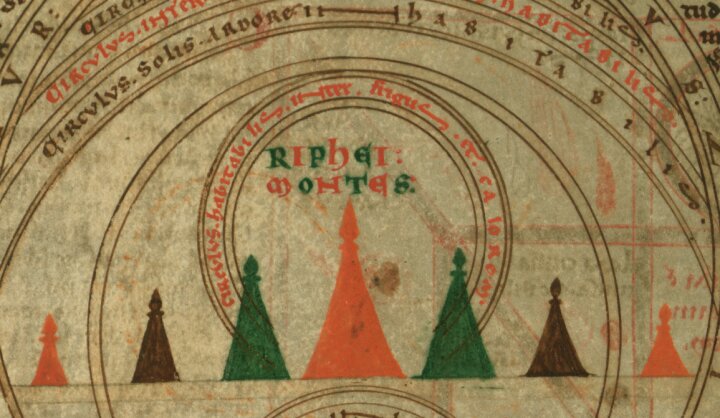

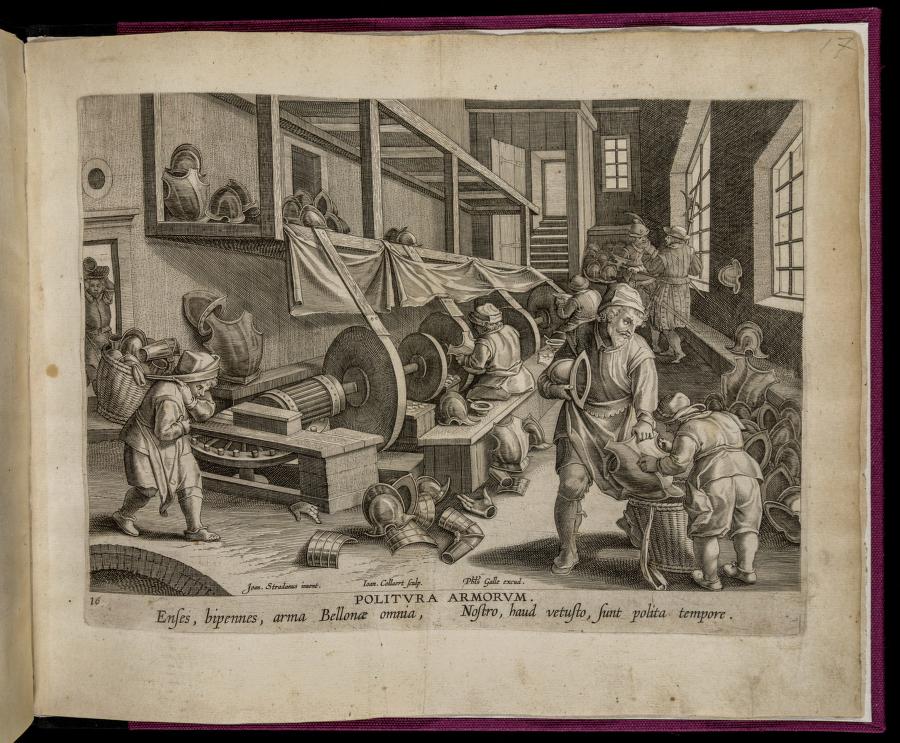

Where Spicer identifies the paradigm shift toward “universal progress” and “scientific revolution” taking place in the work of scientists at the imperial court, another way to see this narrative of progress is, as it appeared in the discourse about the potential of the mechanical arts, to bring about incremental change through their inventions. This sense of improvement first appears in antiquity in Vitruvius (first century BCE) and Pliny’s (23‒79 CE) cataloguing of useful materials and techniques. It then was developed in the Renaissance by humanist authors such as Polydore Vergil (ca. 1470‒1555) in his catalogue of inventors and inventions, De inventoribus rerum (1499), and is then proclaimed widely by artists and artisans as a hallmark of the mechanical arts. For example, in the set of twenty engravings designed (or, as noted in the prints, “invented”) between 1580 and 1600 by Stradanus,[10] materials, such as oil paint, and devices, including eyeglasses, were viewed as distinguishing the less fortunate past from the more advanced present through a process of cumulative and progressive inventions and knowledge creation. This is made explicit in the title page of the series announcing the Nova Reperta (fig. 4) which proclaims the progress of the modern age in relation to the past.[11] The ornate form on which appear the words “Nova Reperta” (New Discoveries) contains a symbolic representation of the Southern Cross, a constellation unknown to the ancients of the northern hemisphere and only named this by European sailors as they ventured into the southern hemisphere in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.[12] The two allegorical figures in the engraving—one who is youthful entering the frame from the left and the other who appears aged exiting to the right—both carry a serpent biting its own tail, the ouroboros, signifying time. Together the two figures denote a new age being ushered in with the discovery of the “new” continent, America, to which the young figure gestures on the map, while the decrepit old era leaves the stage of time. On the intervening ground are displayed numerous objects that defined the new age for Stradanus and his contemporaries, including the compass, on which oceangoing voyages depended, prominently placed opposite the map. Centrally located between map and compass are a printing press and paper, and, in the foreground, cannon and gunpowder. Surrounding these new technologies are stirrups, items for the cultivation of silk, mechanical clocks and watches with their steel springs and precision gears, guaiacum wood to treat syphilis, and distillation with its blown glass vessels and variety of furnaces for producing new liquors and medicinal substances. In this opening image of the print series, Stradanus claims that his own era was profoundly different from the one that was closing, and the prints that follow the frontispiece reflect this view as well. The Latin caption under the plate showing the mechanical polishing of armor (fig. 5) can be translated, in part, as “in our time, not in antiquity.” Thus, the sense that the achievements of the present surpassed those of the ancients is primarily associated with the world of mechanical devices, materials, and techniques.

Politura armorum (Armor Polishing), Nova Reperta, plate 18. Caption: Enses, bipennes, arma bellonae omnia, Nostro, haud vetusto, sunt polita tempore (Swords, battle-axes, all the weapons of war, in our time are polished, not in antiquity)

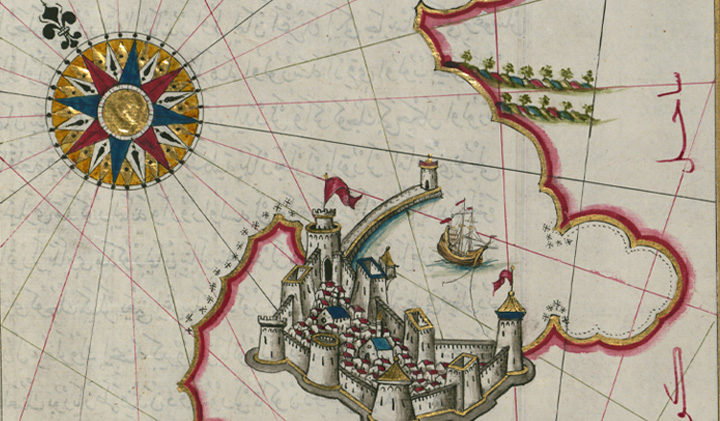

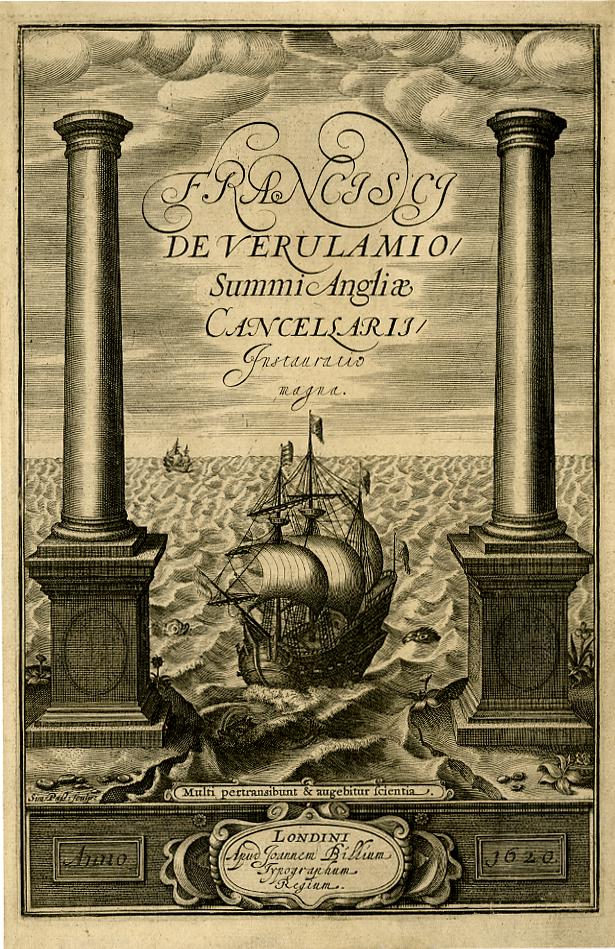

It is true that this narrative of progress would result by the late seventeenth century in a generally held opinion that such progress was characteristic of the “new science.” The works of Francis Bacon (1561‒1626) exemplify this view. Bacon took the coat of arms of Habsburg emperor Charles V (1500‒1558), with its depiction of two pillars and its motto “plus ultra” (yet further), for the frontispiece of his Novum Organum (fig. 6), published in 1620.[13] The two pillars on Charles’s arms referred to the conception that there were boundaries beyond which humans should not pass, as demarcated in ancient times, for example, by the Pillars of Hercules at the Straits of Gibraltar. With this, Charles declared that he would go yet further—“plus oultre”—out past these barriers to extend his empire in unprecedented ways.[14]

Simon van de Passe (Dutch, 1595–1647), Frontispiece, Francis Bacon’s Instauratio Magna, 1620 (London: John Bill), etching and engraving. The British Museum, museum purchase, 1868, acc. no. 1868,0808.3213

Bacon used the device of the two pillars to claim that his “great instauration” (Instauratio Magna), or restoration, of knowledge, and his “new tool” (Novum Organum) would allow human beings to grasp “the knowledge of Causes, and secret motions of things,” that would enlarge “the bounds of Human Empire, to the effecting of all things possible.”[15] Bacon claimed to have replaced Aristotle’s (fourth century BCE) works on logic, which had been collected into a corpus known as the Organon, with the proofs demonstrated by the making of new material things. To reinforce the progressive import of his reform, he pointed to the momentous mechanical inventions of his era that led directly to material and human progress:

Consider the force and effect of inventions which are nowhere more conspicuous than in those three which were unknown to the ancients, namely printing, gunpowder, and the magnet. For these three have changed the condition of the whole world, the first in letters, the second in warfare, and the last in navigation, and from these there sprang innumerable changes so that no empire, sect, or star appears to have exercised a greater power and influence on human affairs than these mechanical matters.[16]

A generation before Bacon, polymath artist Stradanus had pointed to these same “mechanical matters” as ushering in a new age.

The Virtues of Invention, Ingenuity, and Curiosity

Hieronymus Francken II (Flemish 1578–1623) and Jan Brueghel the Elder (Flemish, 1568–1625), The Archdukes Albert and Isabella Visiting the Collection of Pierre Roose, ca. 1621–1623, oil on panel, 37 × 48 1/2 × 1 1/8 in. (94 × 123.19 × 2.86 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, museum purchase, 1948, acc. no. 37.2010

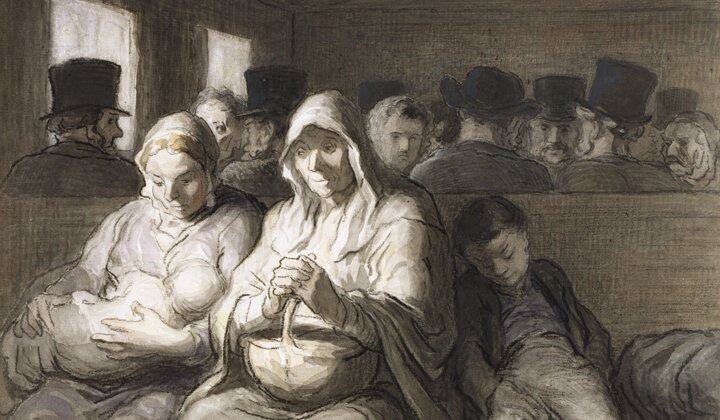

The term invention was often paired with ingenuity in the early seventeenth century.[17] Collections were full of ingenious objects and inventions, increasingly described in the language of curiosity.[18] The genre of “cabinet paintings,” which emerged in Antwerp, the hub of Europe’s international trade network, in the first half of the seventeenth century, illustrates the types of objects in these collections (fig. 7).[19] This painting and others like it informed Spicer’s construction of a Chamber of Wonders at the Walters Art Museum (fig. 8).

The Chamber of Wonders, 2019. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

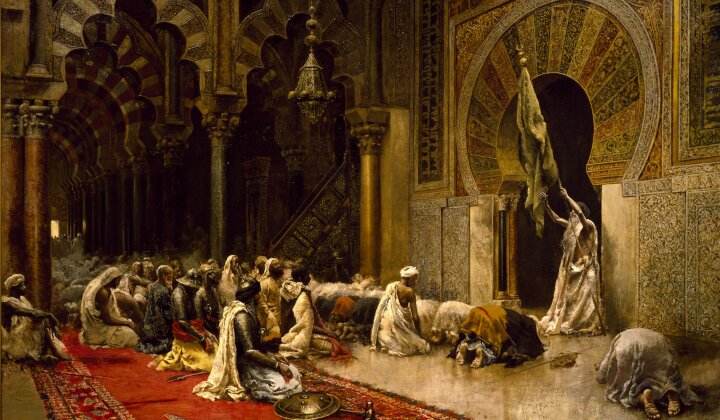

As brilliantly presented by the editors of Trading Values in Early Modern Antwerp, objects collected together and portrayed in Antwerp’s Constcamer and other German-speaking European centers in Kunstkammer (in English, “chambers of art”) functioned simultaneously within systems of commodity and gift exchange, celebrating both literal material and commercial worth as well as an array of symbolic and religious values, above all, piety as defined by the vanguard of the Catholic Reformation.[20] The natural and artificial things contained in these chambers provoked authors and poets, members of Antwerp Chambers of Rhetoric, to articulate new ways of knowing through “viewing, judging, and evaluating” these works of art and nature.[21] These activities came to define the identity of a new viewer, the liefhebber, or amateur. These lovers of the arts expressed particular appreciation for artists who could demonstrate, in Christine Göttler’s words, “Wit in painting, [and] color in words.”[22] Such artists displayed their gheest—their wit or ingenuity—in their craft and strove as well to create vivid word pictures as authors. The objects of the chambers of art, with their natural specimens embodying the artifice of nature, often ornamented or enhanced by the artifice of the human hand, were a primary site of this wordplay about the rivalry between nature and art and between words and things.

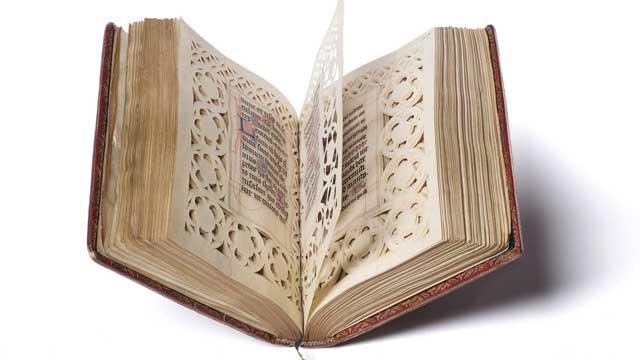

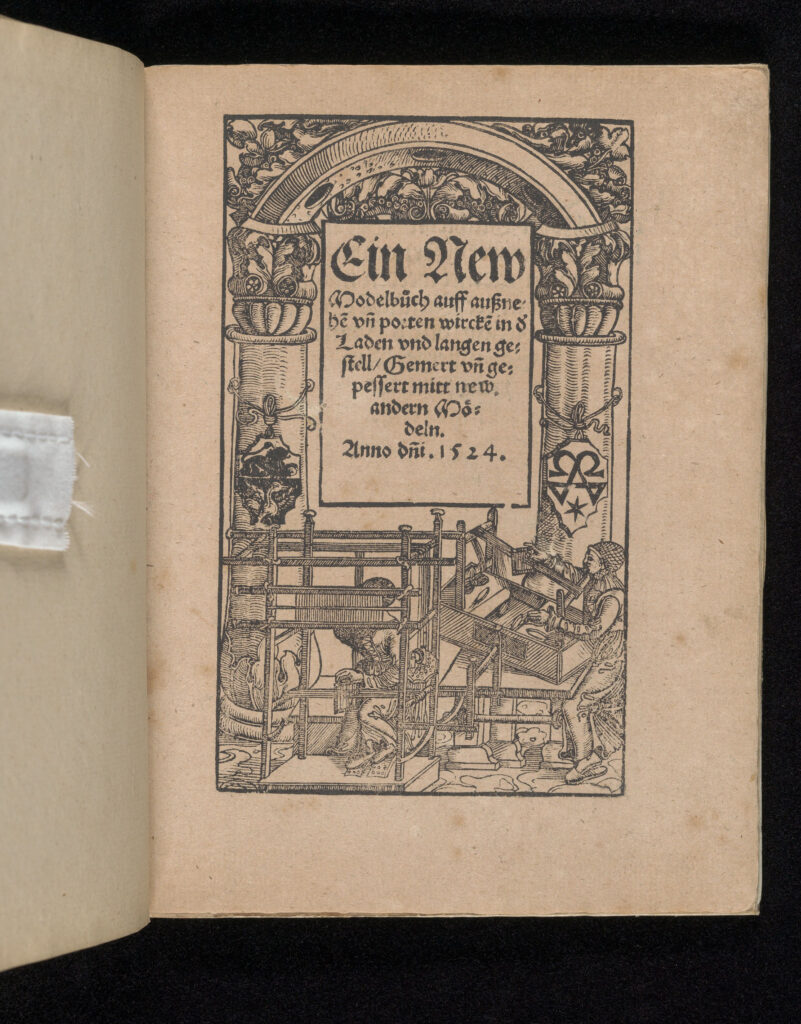

Johann Schönsperger the Younger, as publisher (German, active 1510–1530), Title Page, Ein new Modelbuch, 1524, woodcut, 7 5/16 × 5 3/8 in. (18.5 × 13.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gift of Herbert N. Straus, 1929, acc. no. 29.71(1-31)

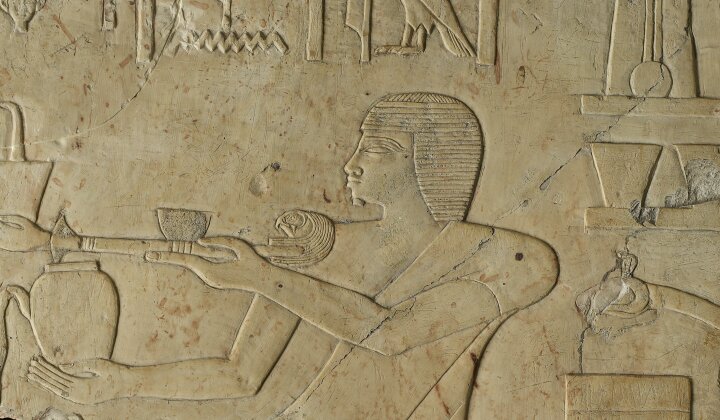

Artists as wordsmiths were in fact ever more numerous in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Indeed, since about 1400, practitioners of all kinds began writing down their techniques. Before this, most such practical books were written by individuals from the scholarly world. In contrast, around 1400, artisans themselves took up the pen, including painters, gunpowder makers, ships’ pilots, fortification builders, and dancing masters, among many others. They all practiced what were called “the mechanical arts,” working with their hands to produce objects and make a livelihood. Their writing signaled a departure from the traditional conception of authorship as a part of the liberal arts and appropriate to the university educated. Moreover, these texts were often on new subjects, not previously part of the ancient canon of texts—such as mining, or the practical medicine of barber surgeons. French humanist and satirist François Rabelais (1483‒1553) ridiculed such texts with titles like: “On the manner of making black puddings, by Mayr […]; On the practice and utility of skinning horses and mares, written by Our Master de Quebecu […, and] The Fart-Puller of the Apothecaries.”[23] Artists, including Giorgio Vasari (1511‒1574), Albrecht Dürer (1471‒1528), Gian Paolo Lomazzo (1537‒1592), and Karel van Mander (1548‒1606), wrote and published such texts, but so did entrepreneurial printers, as they experimented with the new capabilities of their craft. The printer Johann Schönsperger the Younger (active 1510–1530), for example, compiled pattern books for embroidery and weaving and advertised them as “new and improved.” His book of weaving designs experimented with typefaces and book formats, as well as various methods of representing patterns for weavers, lacemakers, and embroiderers. Like Stradanus, Schönsperger proclaimed the novelty of his patterns and the new, “improved” state of his book, titling it Ein new Modelbuch [. . .]. Gemert und gepessert mitt new andern Mödeln (A new design book, enlarged and improved with new designs), making an argument about progress through techniques and devices (fig. 9). This book is just one among many that provided instructions or designs for the reader and simultaneously declared their own novelty and innovation. By the mid-sixteenth century, a large number of such books were being printed, in many vernacular languages, which sold well for printers, as an audience for them rapidly developed. They are often called “how-to” texts, but this can be misleading as they frequently did not intend to teach a bodily technique by written instructions—an impossibility in any case in most trades—but instead sought to attract attention and patronage and to establish expertise, often by making claims to novelty, innovation, and progressive improvement.[24]

Handwork and Material Intelligence

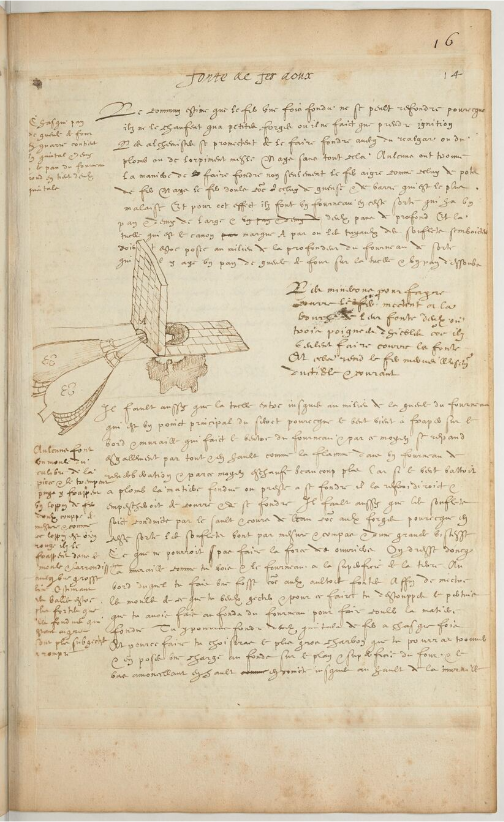

Unidentified French author, Fonte de fer doux (Founding of soft iron), Recueil de recettes et secrets concernant l’art du mouleur, de l’artificier et du peintre, France (Toulouse), after 1580, ink on paper. Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), Paris, acc. no. Ms. Fr. 640, fol. 16r

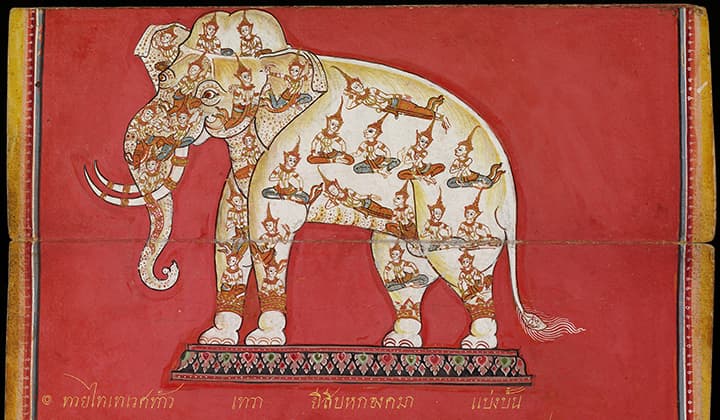

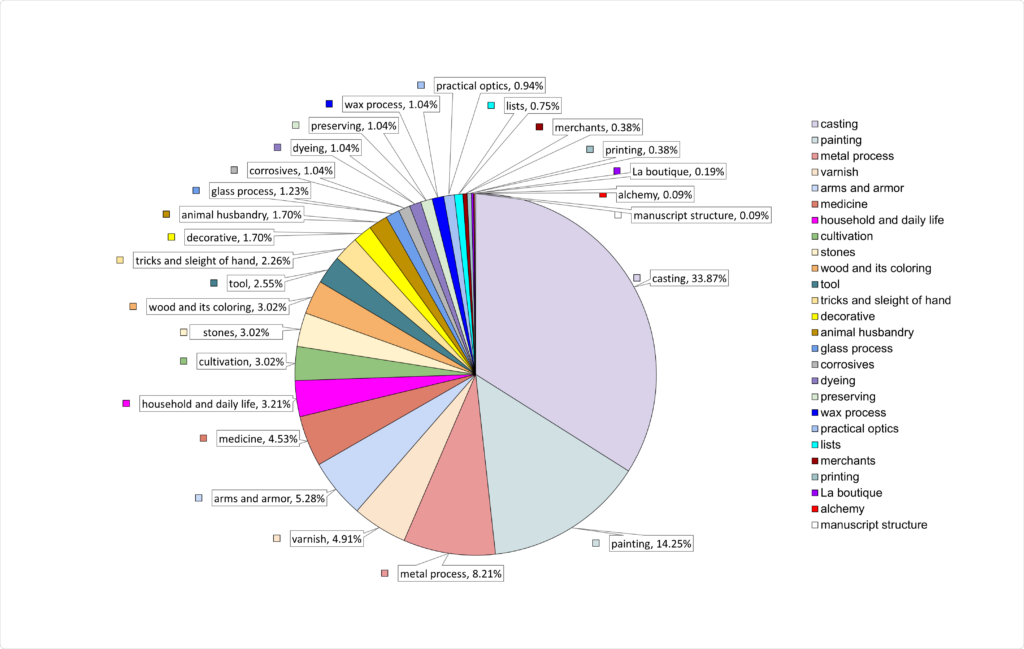

One such text of practical knowledge never made it to print publication, if in fact that is what the anonymous author intended. This Middle French manuscript, BnF Ms. Fr. 640, written down after 1580 by a practitioner—probably a metalsmith—in the environs of Toulouse, includes 170 folios full of detailed accounts of many artistic and artisanal techniques—some were apparently notes to himself, other sections appear to be in the guise of instructions addressed to a reader, while other entries seem to be techniques of trades he observed or about which he had secondhand information but did not himself practice (fig. 10). [25] This compilation is not easy reading, it possesses no particular order, and the text loops around to the same processes in different terms, with many steps of processes varied, or left out altogether. Almost a third of the manuscript deals with metal casting, including casting from life, but it contains accounts of many other types of art objects and objects of daily life, and most unusually, it contains much evidence of firsthand experience and experimenting, thus making it a unique source for studying artisanal knowledge. The largest number of entries in the manuscript is devoted to metalworking, including casting; the second largest group deals with drawing, painting, and color-making practices of many kinds, including paint application, dyeing, staining wood, coloring and painting metal, and making artificial gems. In addition, the manuscript contains much information on weapons production; cultivation, preservation of animals, plants, and foodstuffs; glassworking; varnishes; and much more (fig. 11). This remarkable record of practices includes instructions for making many objects that would fit into a Kunstkammer—it discusses the practices of “Flemish painters,” the techniques of goldsmiths and jewelers, the making of small sculptures and portrait medals, the artful imitation of precious materials of all kinds—jasper, gems, and red coral—and even the making of hybrid animals (fig. 12). In his instructions for preserving animals—“Animals dried in the oven”—he gives an account of a process for an early type of taxidermy of the sort often inventoried in chambers of art (and contained in the Walters’ Chamber of Wonders), which begins by posing the animals, then drying them in a warm oven, after which the text continues, “One gives it a painted tongue, horns, wings & similar fancies. Thus for rats & all animals.” This is not just imitating life and nature in an attempt at lifelikeness; it is also playing on how the human hand can alter and transform nature.[26] This seems just the kind of inventive and ingenious object treasured in the chambers of art and in the Antwerp Constcamer paintings that could spark conversations about the artifice of nature and art. Do we find, then, insights into the virtues of invention, ingenuity, and curiosity in this practical manuscript?

Naomi Rosenkranz, overview of processes and materials in BnF, Ms. Fr. 640, organized into 26 broad categories by the Making and Knowing Project. © Making and Knowing Project (CC BY-NC-SA)

Ms. Fr. 640 mentions “invention” mostly in connection with clever devices, such as a “spinet playing by itself.” Elsewhere in the manuscript, the anonymous author details the use of grains of yellow millet, amaranth, or rapeseed to replace the eyes when making the molds of life cast turtles (fol. 144r, “Turtles,” and marginal note). In a marginal note, the author writes “animal eyes of my invention.” In these exceptionally detailed instructions for making the molds for the life casts, he notes, “Stretch the said head & legs with your little pincers. The head arranged, dexterously place a grain of yellow millet in each eye with pincers, because as soon as they are dead the eyes are burst and putrid. You can do this as well with all other small animals, with some grain of large amaranth, some of small, and grain of rapeseed, & this done, you will arrange the legs, securing them with iron points….” These are the animal eyes of the clever technique that he calls his own “invention.”[27]

Rats with wings, created by Divya Anantharaman and the Making and Knowing Project, following instructions of BnF, Ms. Fr. 640, fol. 130r for “Animals dried in an oven”: “One gives it a painted tongue, horns, wings & similar fancies. Thus for rats & all animals.” © Making and Knowing Project (CC BY-NC-SA)

What of “curiosity”? In Ms. Fr. 640, the terms curieuse or curieusement are always preceded or followed by a verb, e.g., gecter (to cast), observer (to observe), faire (to make), making clear that curieuse (curious or careful) or curieusement (curiously or carefully) here refer not to the positive virtue of curiosity but rather to the manner of skilled work that is “careful” or “meticulous.” Curieusement is also often paired with net(to)yer (to clean), or with net (neat or sharp), meaning a mode of working or the process of creating a sharp impression in molding and casting. The author of Ms. Fr. 640 describes the “Work of the Flemish” (fol. 60v) as the habit of artists to often clean “from their paintbrush the bits of hair which they sometimes leave there, for if these should remain on the work, it would prevent neat working, which they are very careful (curieux) about. In fact, they must work with more diligence” because viewers look at the paintings closely.[28]

Ms. Fr. 640 does not mention any term connected to a virtue of ingenuity or gheest. The French usage, esprit (spirit), is used only once in reference to a volatile spirit in a distillation. The manuscript uses only le naturel (the natural one), which carries the meaning of “native form,” or genius loci, the innate character of a particular place, one early meaning of ingenium. For example, when the anonymous author insists that, in observing nightingales, one must “observe the natural in them,” or, in painting cast-metal crayfish to augment their lifelikeness, le naturel is presented as the unmatched source of visual information that guides the artisan’s work: “As in this & all other things, have always le naturel (the natural one) in front of you to imitate it.”[29] Thus in this text of practice, a reader finds nothing like ingenium meant as a virtue but rather only as an innate property of a thing or material, that must be observed and imitated with care.

Kunstkammers served as sites of judgment, assessment, and valuation, as did artisans’ workshops, artists’ studios, printing shops, meeting places of guilds, and rhetorician chambers, as well as private households with their libraries and collections. In his Schilder-Boeck of 1604, painter Karel van Mander recommended Prague with its many Constcamers as a site ideally suited to “investigate, estimate, and calculate [the] values and prices” of precious works.[30] This ability to judge and to discern became a virtue typical of virtuosi, amateurs, or liefhebbers. If we scour Ms. Fr. 640 for instances of the word “jugement” (judgment), we find all five are about expert working and expertise, such as an entry entitled “Drawing” (fol. 62r): “And by a line of charcoal, masters pass judgment on their apprentices…. Next, re-work all the distinctive lines, & do not keep too close to your panel, but occasionally step away from it to better judge the proportions.” And, for a metal flux, he notes, “Then, invigorate little by little & with judgment the fire” (fol. 123v). And, in instructions for painting on metal, he recommends “by judgment & discretion, put the color on the natural flower or leaf to see whether it comes close” (fol. 158v). Again, “judgment” here is simply about close and careful observation in the workshop in order to come to know the properties, behavior, and best uses of materials.

The inventions of the Kunstkammer of the sixteenth century and their representation in paintings in the seventeenth century informed a new narrative of human progress and an art theoretical discourse that connected art and its appreciation to individual and civilizational virtues, such as inventiveness, ingenuity, and curiosity. The practice-based content of technical writings like Ms. Fr. 640 allows us to see how this art theory rested upon handwork and material intelligence about the innate properties (or virtues) of substances and the “neat,” “clean,” “carefully (curiously)” made objects that demonstrated and proved skilled expertise in judging materials. It was this handwork and practical knowledge that created the ingenious inventions and curious objects that made possible the superior discernment and the identity of the liefhebber. In this sense, Ms. Fr. 640 allows us to see the material intelligence that shaped objects, which in turn shaped their beholders and their new way of talking about the power of art.

[1] See the bibliography included in this volume.

[2] Joaneath Spicer, “The Role of ‘Invention’ in Art and Science at the Court of Rudolf II,” Studia Rudolphina: Bulletin Centra pro výzkum umění a kultury doby Rudolfa II 5, no. 1 (2005): 7‒16, at 7.

[3] Spicer, “The Role of ‘Invention,’” 7.

[4] On Savery, see Joaneath Spicer, “The Drawings of Roelandt Savery, 1576‒1639” (PhD diss., Yale University, 1979); and her entries in Prag um 1600: Kunst und Kultur am Hofe Rudolfs II (Freren: Luca Verlag, 1988), 1:258‒74, nos. 142‒51; 377‒87, nos. 240‒56; and 2:165‒70, nos. 631‒39.

[5] Spicer, “The Role of ‘Invention,’” 9.

[6] Spicer, “The Role of ‘Invention,’” 7.

[7] Spicer, “The Role of ‘Invention,’” 8.

[8] Spicer, “The Role of ‘Invention,’” 13.

[9] Spicer, “The Role of ‘Invention,’” 15‒16.

[10] Stradanus signs each plate “Ioan Stradanus invent.” claiming himself as the inventor of the designs whereas the engraver is then named: “Phls Galle excud.” and sometimes “Ioan Collaert Sculp.”

[11] The series of prints was engraved by Jan Collaert I (1545‒1628) and published by Philips Galle (1537‒1612). The following analysis of van der Straet’s frontispiece owes a debt to an NEH Summer Seminar on Experience and Experiment that Pamela O. Long and Pamela H. Smith held in 2001 at the Folger Shakespeare Library and Institute, Washington, DC. The group constructed a website discussing van der Straet’s Nova Reperta, which is now archived. Components of the site content are used here by permission of Pamela O. Long and the Folger Shakespeare Library and Institute.

[12] One of the subsequent engravings, entitled “Astrolabium,” shows explorer Amerigo Vespucci (1454‒1512) discovering the Southern Cross.

[13] Novum Organum was published as the second part of a larger work, Instauratio Magna (The Great Instauration).

[14] See Keith Hutchison, “The Antiquity of the ‘Injunction’ Non Plus Ultra,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 26, no.1 (2009): 155‒78.

[15] Francis Bacon, The New Atlantis (1627), in Jerry Weinberger, ed., New Atlantis and The Great Instauration (Wiley-Blackwell, 1991), 71. Bacon elaborates these ideas in his English language utopia about the “new Atlantis,” an island where the inhabitants seek inventions and produce knowledge through the methods and with the aims articulated in a more scholarly way in his Instauratio Magna.

[16] Francis Bacon, Novum Organum (1620), Bk. 1, Aphorism 129.

[17] Alexander Marr, Raphaële Garrod, José Ramón Marcaida, and Richard J. Oosterhoff, Logodaedalus: Word Histories of Ingenuity in the Early Modern Period (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019); and Richard J. Oosterhoff, José Ramón Marcaida, and Alexander Marr, Ingenuity in the Making: Matter and Technique in Early Modern Europe (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021).

[18] Neil Kenny, The Uses of Curiosity in Early Modern France and Germany (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

[19] Christine Göttler, Bart Ramakers, and Joanna Woodall, “Trading Values in Early Modern Antwerp: An Introduction,” in Göttler, Ramakers, and Woodall, eds., Trading Values in Early Modern Antwerp (Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 64; Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2014), 9‒37, at 21.

[20] Göttler, Ramakers, and Woodall, “Introduction,” 10‒14.

[21] Göttler, Ramakers, and Woodall, “Introduction,” 23.

[22] Christine Göttler, “Wit in Painting, Color in Words: Gillis Mostaert’s Depictions of Fires,” in Göttler, Ramakers, and Woodall, Trading Values in Early Modern Antwerp, 214‒40.

[23] François Rabelais, The Complete Works of François Rabelais, trans. Donald M. Frame (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 155‒56 and 158.

[24] On books of art and “how-to” manuals, see Pamela H. Smith, From Lived Experience to the Written Word: Reconstructing Practical Knowledge in the Early Modern World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022).

[25] For the digital critical edition and English translation of this manuscript, see Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano, eds., Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France: A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640 (New York: The Making and Knowing Project, 2020), https://edition640.makingandknowing.org.

[26] See Divya Anantharaman and Pamela H. Smith, “Animals Dried in an Oven,” in Making and Knowing Project et al., eds., Secrets of Craft and Nature, https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_502_ad_20.

[27] For more on invention in Ms. Fr. 640, see Benjamin Hiebert, “Spinet Playing by Itself,” in Making and Knowing Project et al., eds., Secrets of Craft and Nature, https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_047_fa_16. On lifecasting, see Pamela H. Smith, “Lifecasting in Ms. Fr. 640,” in Making and Knowing Project et al., eds., Secrets of Craft and Nature, https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_511_ad_20.

[28] For more on this point, see Jo Kirby and Marika Spring, “Ms. Fr. 640 in the World of Pigments in Sixteenth-Century Europe,” in Making and Knowing Project et al., eds., Secrets of Craft and Nature, https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_321_ie_19.

[29] Isabella Lores-Chavez, “Imitating Raw Nature,” in Making and Knowing Project et al., eds., Secrets of Craft and Nature, https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_045_fa_16.

[30] Göttler, “Wit in Painting, Color in Words,” 231.