The occasion to honor Joaneath Spicer and celebrate her critical contributions has opened a door of opportunity for me to reverse the traditional focus of art historians away from intensive study and research on the lives and cultures of artists. Instead, I choose to look at the evolution of this exceptionally gifted individual. While engaged with my own doctoral studies at Johns Hopkins University and later as a member of the Art History Department and Dean of Graduate Studies at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), I had become familiar over the years and decades with the collections and exhibitions at the Walters Art Museum. Encouraging my art history students was my principal concern—to have young developing artists see extraordinary, brilliant artworks that complemented and accentuated their class lectures and individual research. At this point in my life as an art historian and lecturer at MICA I had not crossed professional paths with Joaneath Spicer. In fact, she was not aware of me but as time would reveal, we would soon become unwittingly ‘kindred spirits’ in each other’s lives. (fig. 1).

Leslie King-Hammond and Joaneath Spicer in the Chamber of Wonders, the Walters Art Museum, 2024

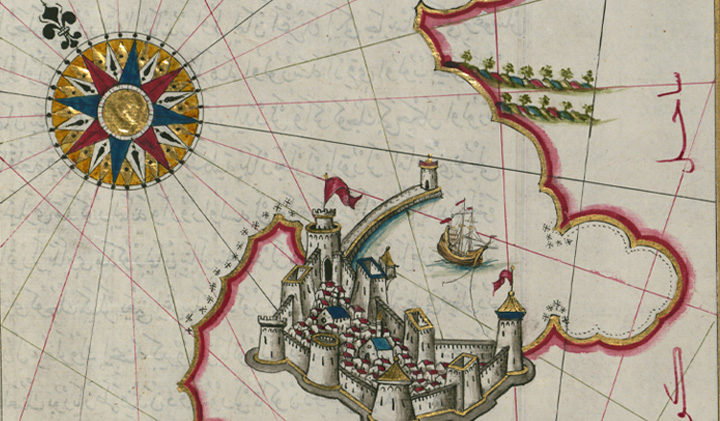

Wandering through the Walters one day, I found myself drawn into the Chamber of Wonders. I was transfixed with the staggeringly rich display of a broad range of diverse artifacts and objects that re-create a space from the era in Europe before the Enlightenment. It was a period of history when individuals were fascinated with rarities from nature, science, and different cultures that they collected and displayed in their homes in special chambers or “cabinets” to demonstrate a level of worldly intellectual concerns for their family, friends, and community. This is not often seen in most museums. Joaneath Spicer’s innovative creation tapped into my imagination and childhood. I had a special shelf in my bedroom for books, crystals, rocks, shells, dried flora, cork, seeds, beads, and curious items I believed to be precious. These objects helped me understand the crazy world into which I was born. Finally, I met Joaneath during her research for the exhibition on Black individuals in the Renaissance, Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe. Although our paths of inquiry and curiosity were different, the nature of our thought processes and our questions about art historical problems became aligned. A growing friendship formed from the similarity of our empathetic concerns, grounded in how art and its histories impacts our understanding of humanity and the role of artmaking across cultures. In recognition of Joaneath Spicer’s enormous contribution to the Walters Art Museum, this interview provides some insight into her evolution as a remarkable scholar, historian, and curator.

Please note: This interview has been lightly edited for readability, with additional information added in endnotes by the editors of this journal.

Let’s start with your early life. Where were you born, who were your parents and what were their occupations? Do you have siblings?

I was born in Chicago, Illinois. I’m named after my mother, Joaneath “Jo” Hill Spicer, who ran an advertising department at Spiegel’s, which was then a major retail mail order company in Chicago. We lived there until we moved to Scarsdale, New York, which was a commuter town in Westchester County for New York City, when I was two. My mother had finished the last two years at the University of Chicago in only one year because she just didn’t have any more money. Apparently, the member of the Spiegel family who was then running the company appreciated her since he offered me a job at birth. My father, Thomas William Spicer, retired as vice President for Finance at Western Electric Corp. He thought I might like to be a secretary. (Sigh.)

I have no siblings. I know that as a small child I had an African American nanny named Ella who had a wonderful smile.

What was your early youth like, your elementary school and high school experiences? What were your favorite subjects and interests? Were there any moments that helped to shape your career?

I was basically a happy and reasonably well-behaved child in a moderate Republican household. (Yes, Republican!) My goals were conventional: I wanted to be a dinosaur specialist (otherwise known as a paleontologist).

Your desire to become a paleontologist reminds me of expectations by my family and society to become a schoolteacher. However, I had a seriously passionate aspiration to become an archaeologist一hardly a conventional goal for a young African American.

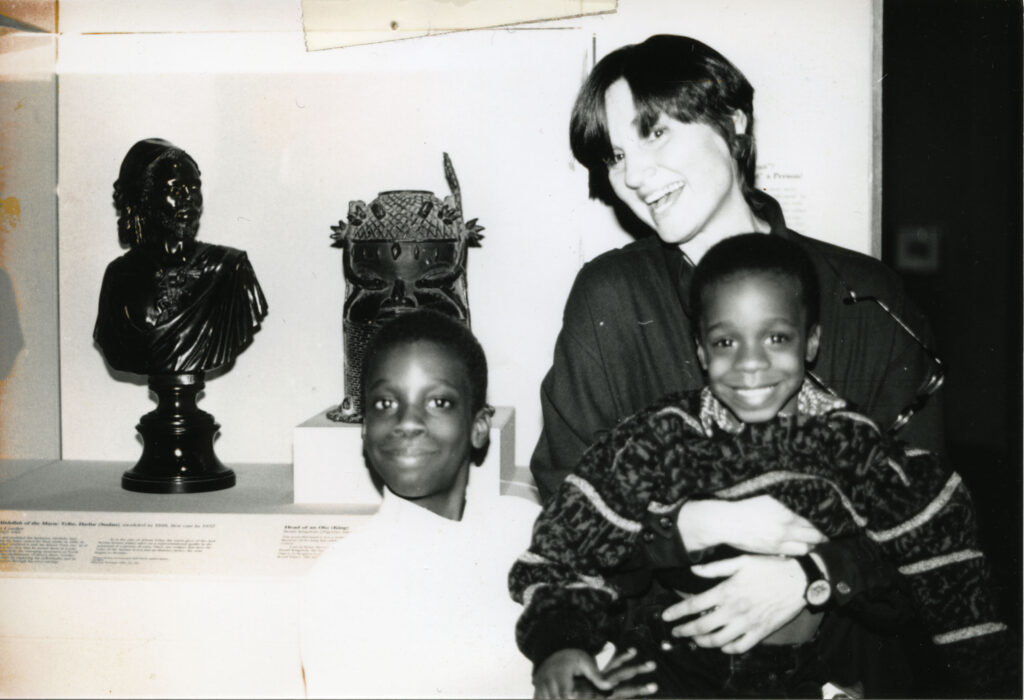

As an adult, when my mentee in a Baltimore mentoring program Vashti Henderson introduced me to her baby brother Nathaniel, I had a sudden flashback and later called my mother to ask, could it be that I had a Black baby doll as a preschooler? Well, she said, yes. I was probably the only white child in Westchester County with a Black baby doll. I can’t say what impact such early experiences had, but I recently came across a joyous photo of Nathaniel, his brother Goodwin, and me in my 1995 show The Allure of Bronze; I had taken them all to see the handsome Africans in the exhibit (fig. 2).

Nathaniel, Goodwin, and Joaneath visiting The Allure of Bronze

It is fascinating that you had a Black doll and an endearing relationship with a Black female caregiver as a child. Your family history brings to mind the research of psychologists Drs. Kenneth and Mamie Clark who in the 1940s asked Black and white children to choose a Black or white doll. Most of the children chose the white doll as “good” and rejected the Black doll as “bad.”[1]This was a critical factor in your early development given the opposite response you had in comparison to the Clarks’ research. It is not impossible to fathom how your queries to locate Africans in early modern Europe might have been inspired by these positive experiences.

What else do you recall from your early childhood memories?

My father was transferred to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, when I was eight and there I attended third to tenth grades. At that point he was transferred back to New York, and we moved to Summit, New Jersey. When I started school in Winston-Salem in the 1950s, I’m sure that I didn’t realize that the school was segregated nor did I know what that meant. I think that it was in my first year at R.J. Reynolds High School (8–12 grades) that the school was one of two in North Carolina to integrate. One Black girl, Yvonne Gwendolyn Bailey, was starting in the tenth grade, and there were 2,000 white students. No one would explain it all to me, and for the first time I tried to think through something hard. I never had the chance to speak to her until decades later when we met at a restaurant in southern Maryland. I felt awkward and just wanted to tell her that her courage had made such an impression on me—that I hoped somehow to pay it forward. I don’t know how to talk about our meeting without sounding corny. There is a dedication to her in the Curator’s Acknowledgments for the catalogue accompanying my exhibition Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe.

Otherwise, in school, I liked history class and would have tried out for a girls’ golf team if there had been one.

Did you have any opportunities to visit museums and cultural institutions during those early years? What impressed or fascinated you during that period of your young life that prompted your interest in a curatorial career?

My first art museum visit was in college. I visited zoos and the natural history museum in New York City, though. I never thought about an art museum career, although if I had known that there was such a thing as curator of dinosaurs, I would have gone for that. It wasn’t encouraged at Smith or Yale to pursue that path. What eventually drew me to curatorial work was a love of objects, and I felt the need to change my life in a meaningful way after my first bout of breast cancer in my forties, resulting in my move from academia to the museum world.

Where did you attend college and graduate school? What were your majors? What was the focus of your doctoral dissertation?

While I was in high school, I had looked for a college where I could major in sports, but I really wasn’t good enough as an athlete, so I went to Smith College, in Northampton, Massachusetts, instead. That was a good call. I majored in art history. The classes in that department were the only undergraduate courses in which professors challenged you to “figure it out.” And I got into the junior year in Paris program in spite of jagged grades (due to migraines). After that, I barely scraped into Yale (jagged grades again) to do a PhD in art history, and I hit my stride. My dissertation was on the drawings of the Netherlander Roelandt Savery.[2] A highpoint of my research at that time was discovering that over eighty drawings of peasants, inscribed naer het leven (from life), considered among Pieter Bruegel’s most important were actually created by Savery while he was working in Prague for Habsburg Emperor Rudolf II just after 1600. That research resulted in my first article.[3] Supported by a Fulbright award and funding from the National Gallery of Art, I lived in a tiny apartment in Leiden (Holland) and crisscrossed Europe by train researching drawings. But a Dutch student decided that I must have learned of his seminar paper on the handwriting on the drawings and that I couldn’t have worked up a major discovery myself. So…the student took up the issue, resulting in newspaper articles accusing me of doing research by using “feminine wiles” and that I was an “arm of American imperialism….” After ten years, two acts of Parliament, etc., my former dissertation advisor located a letter from me (written before the article) that described my new assumption on Savery’s authorship. The University of Amsterdam launched a second investigation, issued a private apology, and I was allowed to respond to the most recent editorial. Great, but ten years is a long time.

During which time, while I was dealing with the “naer het leven affair,” I took a job at the University of Toronto where I taught for over a decade. It’s a great city, with an equally great university and students. But! While I was there, I made the poor, nearly fatal, decision to marry the wrong man. Got a separation and divorce. And I also had breast cancer.

What role has travel played in your professional development?

Travel taught me how very different and unexpected peoples’ perspectives and life experiences can be and therefore to look for such stories behind works of art. In early November 1989, I found myself standing in a group of Germans next to the Wall in West Berlin when the first hand came through. It was the most stunning sight in my whole life.

Which countries had the strongest impact on your career and why?

I think the most impact was from what used to be called the Eastern Bloc countries and also Russia before the collapse of the Soviet Union,[4] which I visited first for my dissertation and subsequently for further research and conferences. Early lessons I took from these visits were in developing a “work around” or at least a calm demeanor to get done what needs to be done even when you’re seriously stressed from being followed or bullied.

Describe your first curatorial appointment. Where was it, and how long did you stay in the position?

Ah! I am in my first curatorial appointment: I even have the same title as when I started. I’ve been the James A. Murnaghan Curator of Renaissance and Baroque Art at the Walters Art Museum for over thirty years (fig. 3).

Joaneath not long after she came to the Walters Art Museum as curator, 1994. Photo: Aaron Levin, 1994

When did you become a curator at the Walters Art Museum, and what were your first challenges in that position?

I came to the Walters in January 1990. I was hired the previous summer, but I had just had my first cancer operation (of three), and radiation therapy was next up before I could move to Baltimore.[5] The day I started at the museum, my initial challenge was that I didn’t know exactly what curators did! So I got the catalogues for the upcoming auctions (as I had for a long time advised collectors in Toronto). After lunch on my first day I went into Gary Vikan’s office—he was then-assistant director for curatorial affairs, essentially chief curator—and offered the view that the Walters needed a Black prince, and an idealized painting of one was coming up for auction in New York. We were the underbidder in the auction, and it’s just as well. We now have an infinitely more impressive Black prince, indeed I have identified him as an actual historical figure—the portrait of Prince Aniaba of Assinie as Balthazar (fig. 4).[6]

Possibly workshop of Hyacinthe Rigaud (French, 1659–1743), Balthazar, ca. 1700, oil on canvas, 34 3/4 × 27 1/4 in. (88.3 × 69.2 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 2018, acc. no. 37.2938

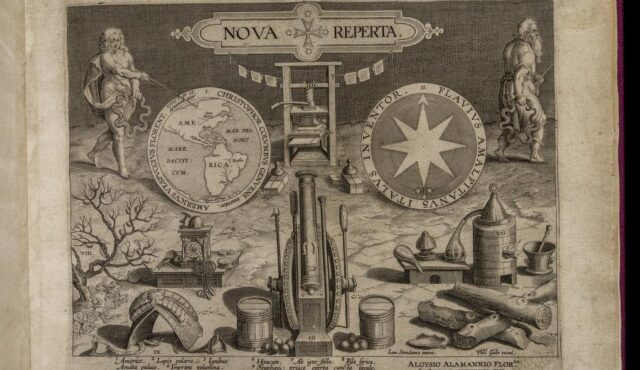

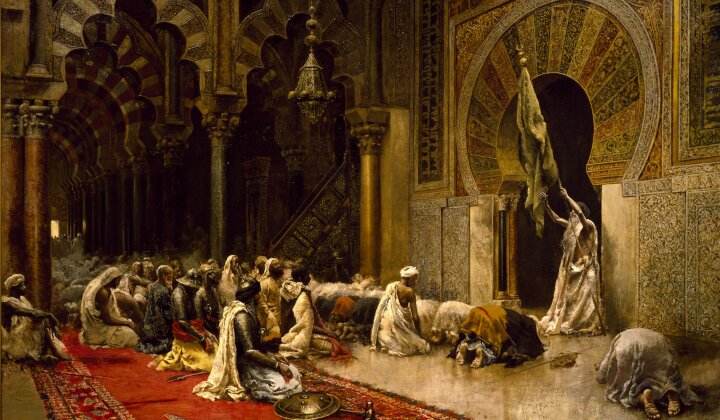

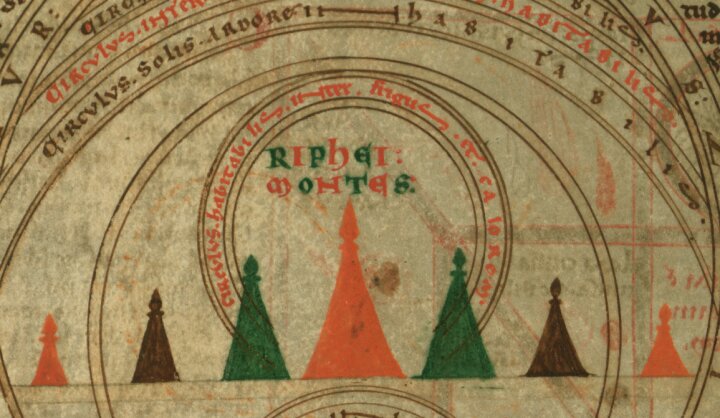

How did you start the process to re-create a Chamber of Wonders?

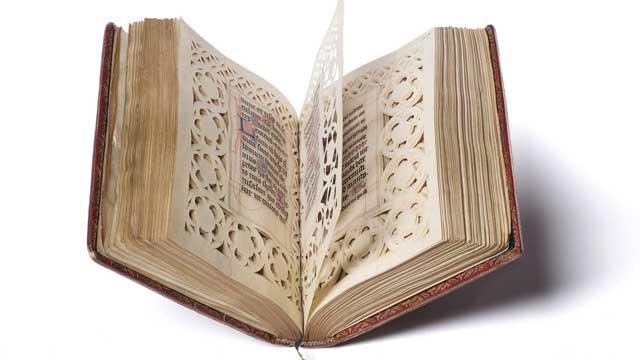

It started with a dilemma. All the arms and armor collections had been installed together where the café is now, but Gary (by that point the museum’s executive director) wanted a café there, by the main entrance. So, all the arms and armor were distributed to the curatorial areas. We were starting to plan for a reinstallation of the Palazzo building, so suddenly I had to think how to install arms and armor with paintings and sculpture. My dissertation-related submersion in the collecting approaches of the Habsburg family flooded in with the solution. A suite of adjoining spaces off the courtyard was perfect for a fictive re-creation of a Habsburg-style collection of the seventeenth century that would be entered through the hall of the family’s personal arms and armor, then the collector’s private study (fig. 5), and finally the large, more public chamber. So the Chamber was actually born of a quick pivot. I didn’t realize how much work it would be to go through a zillion sixteenth- and seventeenth-century inventories so that I would know what to look for in the museum collections, nor did I realize how resonant it would become with the public as well as with other scholars. Planning and installing such a collection give you insights as to how people relate to objects that university-based scholars are just not privileged to experience.

Joaneath working on the installation of the Collector’s Study, ca. 2005

Why was it important for the Walters to have such a collection?

Not everyone thought it was important at the time, but Gary was very supportive. I just kept going. The value of highlighting cultural exchange and respect wasn’t recognized as a major issue then as it is now. It was a very tumultuous time (much like now) and a Chamber of Wonders was your own connect-the-dots challenge: not to draw a rabbit or a car, but to locate yourself in the larger scheme of things. I’m also very big on making spaces look comfortable for the art as well as the people. In the Collector’s Study, the objects rest on velvet pads with no intrusive labels inside the cases. I find it very soothing. It’s humbling to see the installation as a whole referenced as iconic or as a model for a museum in Rome.[7] A recent scholarly book on the Habsburg Kunst- and Wunderkammer tradition by Jeffrey Chipps Smith ends with a photo of the Walters Chamber of Wonders.[8] That made me so proud.

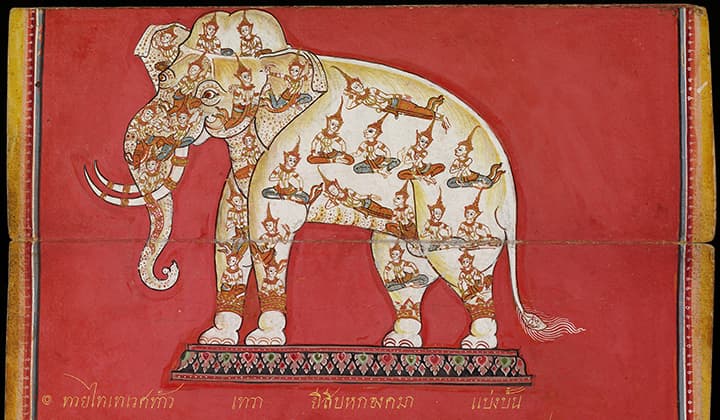

You have accomplished an enormous amount of research on Black presence in Renaissance Europe. How did this interest become a compelling platform for your research and the subsequent exhibition on this subject?

Gradually. Looking back now I realize how much impact the Henderson children had on me as a person, an art historian, and a curator. One topic explored in the 1995 exhibition and catalogue The Allure of Bronze, Masterpieces from the Walters Art Gallery was the liveliness that the skillful use of bronze could impact to dark brown skin. My investigations in developing the show were surely prompted in part by wanting them to see themselves in handsome Black faces.

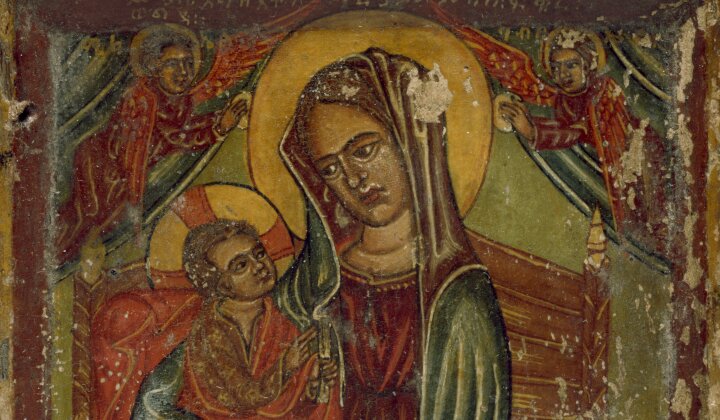

By the end of the 1990s I was hearing more about academic research projects in Europe and England on the African presence in Europe and especially the role of Duke Alessandro de’ Medici, whose daughter is memorialized in a Walters portrait, the earliest known European portrait of a child of African ancestry (fig. 6). So I was in, and gradually it became clear what a wealth of material was waiting to be teased out…and what an impact a new interpretation of this extensive imagery today could have on how we all see ourselves and others.[9] Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe (2012) had and continues to have significant impact. After three printings, we made it a free ebook.

Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci; Italian, 1494–1557), Portrait of Maria Salviati de’ Medici and Giulia de’ Medici, ca. 1539, oil on panel, 34 5/8 × 28 1/16 × 3/8 in. (88 × 71.3 × 1 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, acquired by Henry Walters with the Massarenti Collection, 1902, acc. no. 37.596

What are your current and future curatorial and research initiatives?

I have recently decided to retire this year. Retirement will offer great opportunities but also limitations. Within the African diaspora in Europe, I have prepared a focus installation on a remarkable painting, Moses and his Ethiopian Wife (on loan from the Rubenshuis Museum, Antwerp). Then an essay is due on Rembrandt’s Black nude for a book on Rembrandt and daily life edited by a Rembrandt specialist. I would love to see my research project on Prince Aniaba of Assinie (WAM’s Balthazar) and Louis XIV as an exhibition but will write the book. For fifteenth-century Italy, I am publishing my discoveries on Donatello’s unrecognized adaptations of a Roman statuette (resulting from research on Walters’ paintings) and look forward to finishing my work on our famous Ideal City (fig. 7). For the Chamber of Wonders, I continue to work up aspects of the book through conference papers and essays, including a related, introductory essay for an exhibition the Louvre is organizing on experiencing nature through art at the court of Rudolf II. All very exciting, but I will miss the useful pokes and prods of Walters colleagues!

Unidentified Florentine artist, The Ideal City, ca. 1480–1484, oil and tempera on panel, 30 1/2 × 86 5/8 in. (77.4 × 220 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, acquired by Henry Walters with the Massarenti Collection, 1902, acc. no. 37.677

Why do you feel it is important to work with and mentor curatorial interns, fellows, and junior colleagues?

They’re the future. Many have gone on to really distinguish themselves in the field.

As you think about your role at the Walters Art Museum and in the field of art history, what do you hope will become your legacy?

“Legacy” is a big word. Curators come and go; we all want to feel that our efforts were positive. I would like to think that my commitment to the public humanities that is essential to museum work, tied to rigorous scholarship prompted by an imaginative use of the hypothesis to tease out the backstory, has encouraged our wider audiences to experience the exhilaration of shared discovery. That the fundamental humanity, the hopes, fears, and joys that form the backstories not only of Prince Aniaba and all those who made up the African diaspora in early modern Europe but also of so much of the world’s art throughout the ages come from a reservoir from which we can all continue to draw.

If we don’t both examine and nurture a sense of our collective past, the present, not to mention the future, could come unmoored.

[1] K.B. Clark, The Dark Ghetto: Dilemmas of Social Power (New York: Harper & Row, 1965).

[2] “The Drawings of Roelandt Savery, 1576‒1639” (PhD diss., Yale University, 1979).

[3] “The ‘Naer Het Leven’ Drawings: By Pieter Bruegel or Roelandt Savery?” Master Drawings 8, no. 1 (1970): 3–82.

[4] The former Czechoslovakia and East Germany; Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, and Romania.

[5] Joaneath wrote an undeniably personal essay on the topic of breast cancer in “Criteria for Breast Reconstruction Surgery: Another Viewpoint,” Annals of Plastic Surgery 6 (1995): 1–9.

[6] When the acquisition became official, curatorial staff gathered outside of Joaneath’s office and gave three cheers for this purchase.

[7] Fernando Salvetti, et al., “Reshaping the Museum of Zoology in Rome by Visual Storytelling and Interactive Iconography,” International Journal of Advanced Corporate Learning 16, no. 2 (2023): 81–92, at 89.

[8] Kunstkammer: Early Modern Art and Curiosity Cabinets in the Holy Roman Empire (London, 2022).

[9] For a video of Joaneath discussing this painting, see “Curator Talk: A Child of African Ancestry at the Medici Court,” YouTube, 1 Dec 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nsh6S9nUSvU.