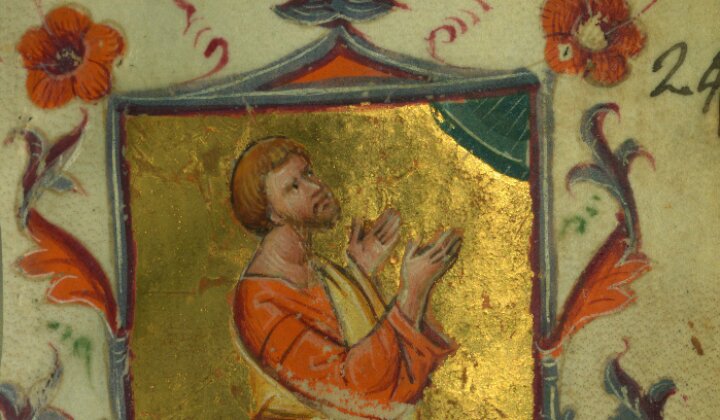

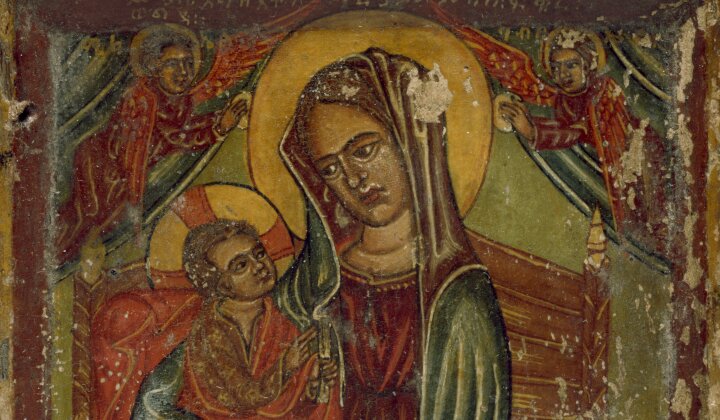

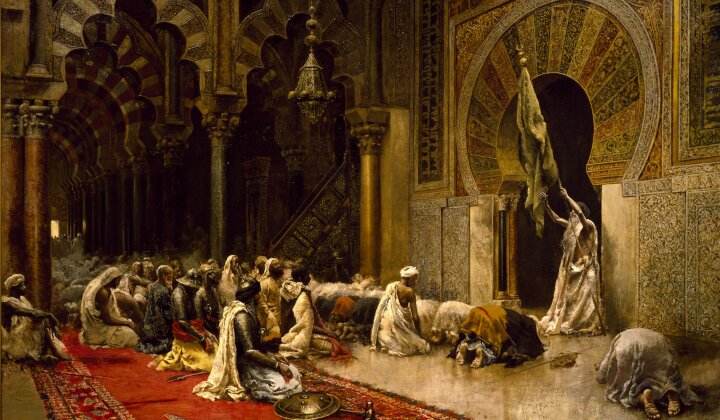

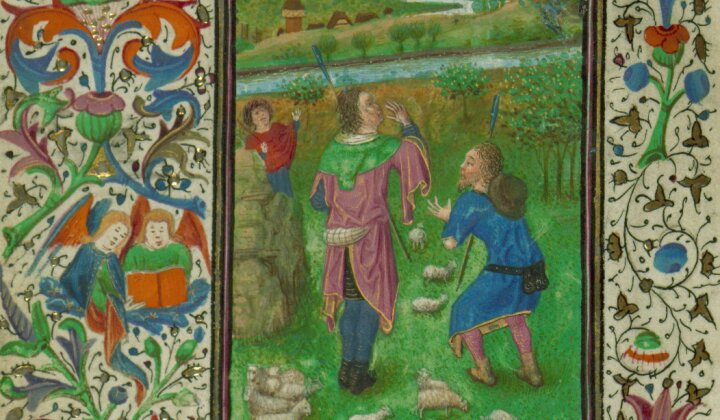

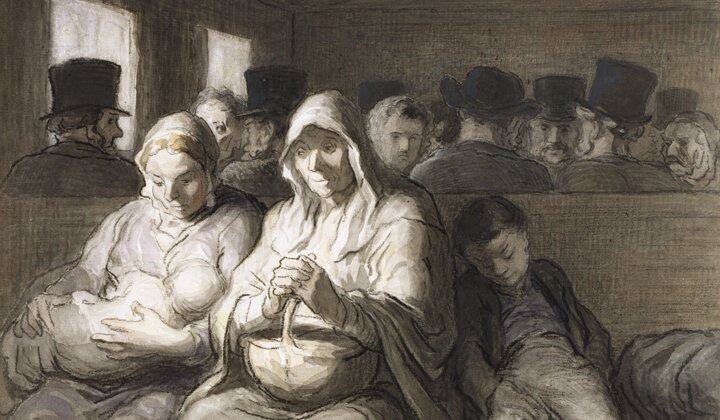

Walking into the Chamber of Wonders at the Walters Art Museum—a re-creation of a curiosity cabinet that might have been assembled by a seventeenth-century nobleman in the Southern Netherlands—for the first time over ten years ago was revelatory for me. It was delightfully disorienting, and it sparked the kind of mental implosion I treasure as someone who likes to observe and think. Any boundaries you thought were real because they are reinforced by museums, keeping art and natural history and books separated in silos, for instance, are shattered (a mental shattering of this kind happened to Michel Foucault when he read Borges’s story about the Chinese encyclopedia, a kind of literary version of a curiosity cabinet, which inspired his seminal book The Order of Things [1966]). Why are these disparate things arranged in this way, a visitor might ask? I believe this is the job of art and literature and, hopefully, museums—to provoke such questions, to help us wander across disciplinary boundaries that may be keeping us fenced in. Visitors to the Chamber can experience a mental and visceral unmooring every time they go through it.

The Chamber of Wonders, the Walters Art Museum

For the better part of my life, making my living as a visual artist and a writer, I’ve been exploring the human urge and need to order nature—not only how we frame the world with our minds using tools like language, but also how we bend nature to our will in the material world.

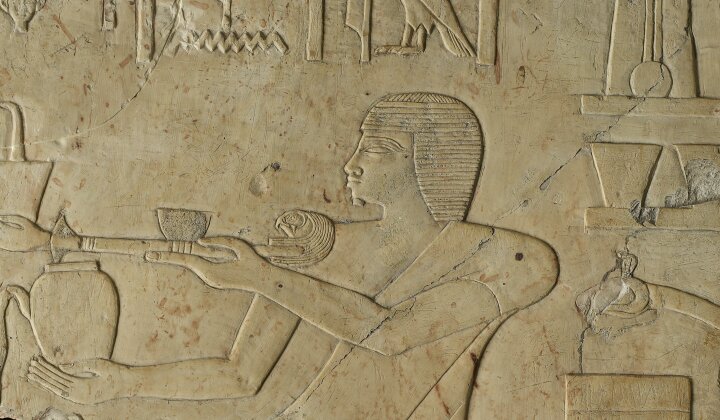

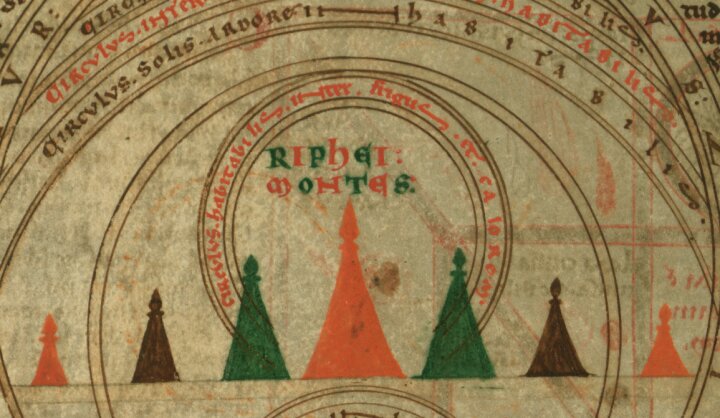

More specifically, I’m interested in the history and process of naming and ordering nature—what happens when we join words to a world that doesn’t have words on it. Nature is an interconnected and dynamic, complex and holistic system, but in order to communicate it through language we have to fragment it, draw lines between things—chop it up, and label the pieces. We also, necessarily, reduce complexity. For instance, we cannot give every individual tree a name, there are just too many—so we name trees as members of species and we create systems of classification to order them based on ancestral relationships. It’s not Joe or Harriet the tree, but sugar maple or white ash.

Although this naming and ordering functions pretty well, by fragmenting nature and reducing it to simplified concepts, we lose sight of the world as a whole, and aspects of its richness. By being so focused on creating systems for communicating and understanding nature, though necessary, we sometimes miss what can be learned by studying nature without drawing boundaries.

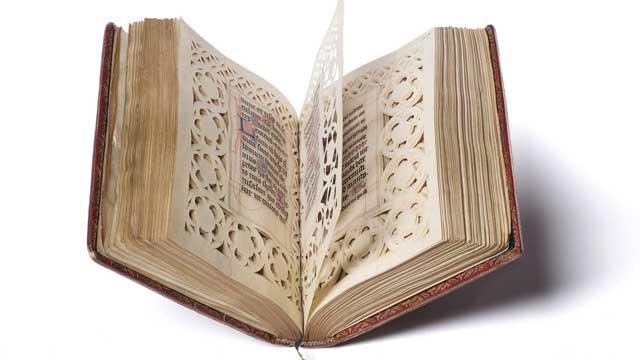

In my work—using words and paint and other materials and media to communicate thoughts and ideas—I advocate for a kind of walking without lines, mental trespassing, encouraging us as humans (myself included) to temporarily suspend, or transcend, the boxes and categories we’ve come to depend on. Once you fragment the world you’ve changed it. The sum of parts can be enriching and beautiful, but it can never make the whole whole, because we cannot create enough fragmented and named units to fill all the spaces in between the pieces. You can carve up the color spectrum into thousands of fragments and name them, but adding all those named colors together does not remake the spectrum. The spectrum is whole and indivisible—once you divide it you have created something different.

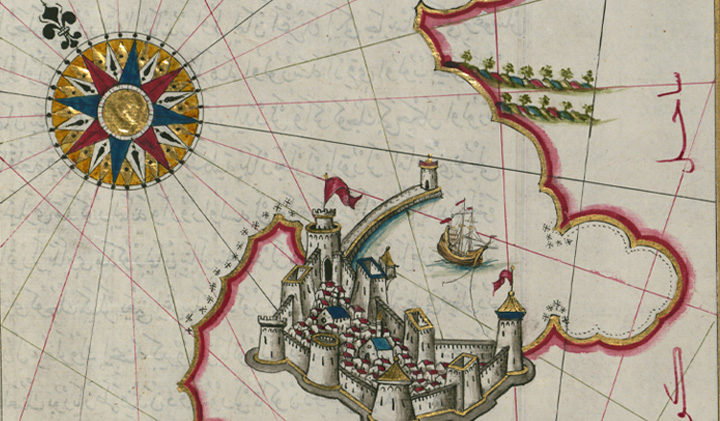

In order to communicate and come to know the world we have to create a map to navigate it, but the map is always just a map, it can never be, in the words of philosopher Alfred Korzybski, “the territory it describes.” A map the same size as the world with the resolution of the world would not be useful (see Jorge Luis Borges’s story On Exactitude in Science [1946]). The human brain, as Aldous Huxley wrote in his book The Doors of Perception (1954), evolved as a “cerebral reducing valve.” Essentially what Huxley says is that our minds edit out constant complexities, and keep only what is necessary to get through the day, or across the territory. Huxley experiments with the psychedelic drug mescaline to see what it might be like to temporarily suspend the reducing valve. He describes this experience as the doors of perception being blown open. In that state, he says, we can momentarily glimpse and absorb the vast complexities of the world with our minds.

The Chamber at the Walters was the first curiosity cabinet I had ever seen outside of old engravings. Cabinets of Wonder, or Wunderkammern, of course are not new. The Chamber of Wonders is a modern reworking of an old convention made to educate and to inspire. It is the creation of Joaneath Spicer, who is being celebrated in this volume.

The word “wonder” in the room’s title is appropriate because I think wonder is generated in part by the unexpected and the awesome—episodes when we experience something unlike anything we have experienced before—a gentle opening of the doors of perception.

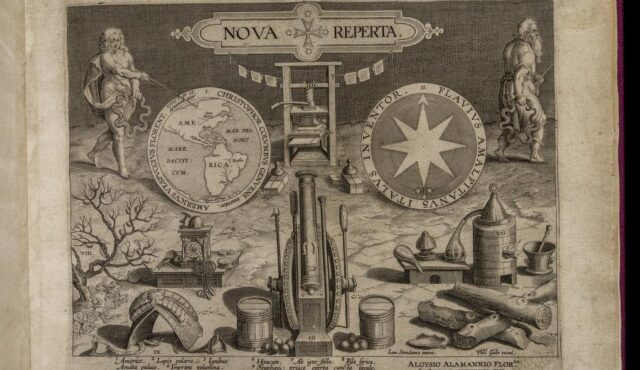

Curiosity cabinets were collections of objects amassed and displayed largely by aristocrats and wealthy European merchants beginning in the sixteenth century. They juxtaposed natural history objects, like bird eggs or the skin of a crocodile, geological wonders, and objects made by humans—from vessels to paintings. These collections and displays were idiosyncratic to the collector, and reflected their varied superstitions and beliefs. They were precursors to museum collections that eventually became more organized by discipline—art or science, for instance.

What followed from the cabinet of wonders, historically, were attempts to create a more systematic way of ordering things, based on how we were coming to understand and perceive the world.

In the eighteenth century, Carl Linnaeus produced and promoted his system for the classification of organisms. Linnaeus assigned two names, one generic and one specific (like Homo sapiens for humans), to every creature that was deemed distinct enough from others to be given a name. He named them and put them in what were intuitive categories, nested boxes in a kind of hierarchical arrangement that resembled a tree, from Order and Family down to genus and individual species. It was this map of nested categories that helped Charles Darwin envision his tree of life, the basic structure of which was, years later, for the most part verified by the genetic revolution in the twentieth century. This was no longer just a bunch of creatures that seemed to fit into categories based on family resemblances—it was a history of life where everything was related by common ancestry going back hundreds of millions of years.

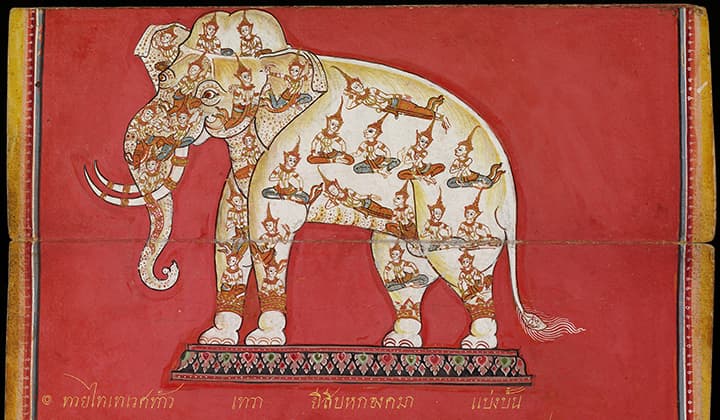

Still, nature will never fit neatly into the boxes we create to describe and communicate them. When diversity is examined at a certain resolution we realize that the demarcating lines we draw between things on the intricate continuum of life are, at least in part, fictions. Even Darwin acknowledged this in On The Origin of Species (1859) when he wrote“I look at the term species as one arbitrarily given for the sake of convenience to a set of individuals closely resembling each other.”[1] Nature will never fit our words and definitions, because words don’t exist in the world, we put them there—these are just maps, tools to help us navigate. In the words of Stephen Jay Gould, “Nature mocks our attempt to encase her in a straightjacket… Much of nature is messy and multifarious, markedly resistant to simple mathematical expression.”[2]

We like maps and even prefer them to the land that they represent, because they are worlds made in our image, born of the constraints set by the limits of our minds, our own scale and orientation.

But there are dangers in mistaking the map for the territory—mistaking the representation for the thing it represents. For a fish, taking an artificial lure, a representation of the food it eats, for instance, can mean certain death. René Magritte offers a similar caution in his work The Treachery of Images (1929) where he paints a pipe and writes beneath it, “this is not a pipe.” A child (or an adult for that matter) may look at the picture and say, “mommy that’s a pipe,” but the parent should be gently encouraging them to see that it is not a pipe, it’s a picture of a pipe. In preferring the world that is ordered and reduced by our minds, the neatness of the map instead of messy actuality, we eventually try to force the world to fit into a version of our maps. Think dams, fences, diversions, highways, lines we draw to harness the world, make the messy curves straight, give the illusion of permanence in a constantly changing environment.

Considering all of this, for me, one of the big questions has been—how can we continue to use these tools of representation like maps, or names or taxonomic systems, while also reminding ourselves that the maps are not the territories, that words are not things, that the taxonomies we use to describe nature are not nature, that the actual world is something different, something ineffable, wondrous, and magical, and to a great extent unorderable?

We know a lot more now than we knew when the cabinets of curiosity were in fashion (and we probably think we know more than we actually do—a constant with humanity) but there was a charm to the order of things when we knew less, when our attempts to juxtapose things were based more on superstition than science, when we still believed in mermaids. And there was (and is), we are finding, a value to ordering and reordering things in collections such as these. Every time you rearrange the furniture, you see things differently, the lines of text are broken and rewritten. Mixing stuff up helps to reduce complacency, helps to remind us to ask ourselves, what do we really know and what do we really not know?

The Chamber of Wonders, the Walters Art Museum

We gained a lot through the map made by Linnaeus; his standardized system still allows us to communicate the units of biodiversity across languages, across the world, defying Babel. The Chamber of Wonders asks us, what have we lost in the process through the human need to find and make order.

In this vein, the Chamber of Wonders recalls one of my favorite short stories, a beautiful jewel written by Ursula K. Le Guin called She Unnames Them (1985). In the story Eve goes through the Garden of Eden unnaming everything that Adam had just named (labeling the animals was the first task given to him by God). Eve feels that once the animals were named, a barrier was created between us and them—between humans and the rest of nature. By unnaming the animals Eve gives us an opportunity to see what boundless nature might look like.

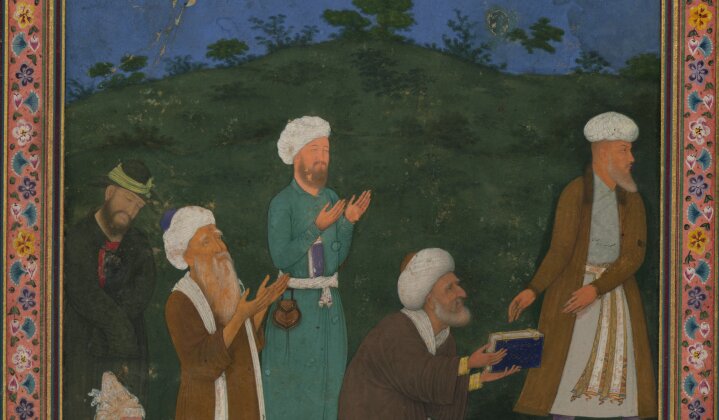

Similarly, studying indigenous ways of naming and ordering nature, often called “folk taxonomies,” can provide alternative perspectives that are deeply valuable. On an island in Micronesia called Pohnpei, where I spent time, the native people have a different story of how the plants received their names. As opposed to the Biblical story in Genesis where Adam tells the organisms what they will be named, two boys go out in the forest and ask the plants what their names are.

Joaneath’s creation temporarily blows open the doors of perception, props open the cerebral reducing valve, allows us to throw away the map, obliterates boundaries between art and artifact, enables our minds to reset, to be open, to feel wonder. Perhaps that’s what wonder is, the temporary suspension of all the known, or what we thought we knew—a return, for a few moments, to a childlike state, to a less mediated way of seeing and experiencing the world, where the tools that we depend on so much, particularly language, are turned off.

I’ve never met Joaneath Spicer, but I feel like I know something of her after experiencing her work through the Chamber of Wonders on a visit to the Walters Art Museum. She has taught us through her creation that novel associations have the potential to bring us novel perspectives.

[1] Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968), 108.

[2] Stephen Jay Gould, Dinosaur in a Haystack (New York: Harmony, 1995), 3.