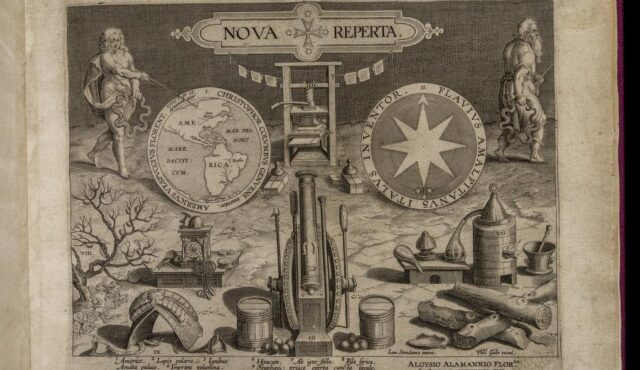

A Painting, An Exhibition, A Question about Still Lifes

Giuseppe Cesari, called Cavaliere d’Arpino (Italian, 1568–1640), Perseus Rescuing Andromeda, ca. 1593–1594, oil on lapis lazuli backed with slate, 7 15/16 × 6 1/8 in. (20.2 × 15.6 cm). Saint Louis Art Museum, museum purchase, 2000, acc. no. 1:2000.

Starting in 2007, I began to investigate the use of stone supports for painted images, a practice that originated in Rome around 1530. My goal was to fully understand a small oval painting on lapis lazuli that I purchased in 2000 for the Saint Louis Art Museum where I am the Senior Curator of European Art to 1800 (fig. 1). It was the creation of Giuseppe Cesari (1568‒1640), now commonly known as the Cavaliere d’Arpino, following the knighthood conferred upon him by Pope Paul V in 1620.[1] In order to place this production properly in the context of painting on lithic supports, I started trying to find as many examples of stone paintings as I could, eventually compiling a database of nearly 1,400 examples. My research led to the 2022 exhibition Paintings on Stone: Science and the Sacred 1530‒1800. [2]

The show focused mostly on mythological and religious subjects as well as portraits. In researching and then analyzing these works, I came to understand that the use of stone supports enhanced the meanings of the subjects painted upon them. Painting a story that included the body of Christ on a stone panel, for example, evoked the actual presence of Christ’s body lying on a stone slab. Portraits painted on stone, on the other hand, could underscore the sitter’s strength of character or, when a rare and expensive stone such as porphyry was used, his wealth and power. Since the show included only one example of a still life on stone, I did not fully investigate the meanings of still lifes on stone in the course of preparing the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue. This article, conceived during the last month of the exhibition’s run (February 20 to May 15, 2022), is an attempt to redress this omission by focusing specifically on the subject of still life subjects painted on stone and is not intended as a discussion of the subject of painting on stone in general.

Gerard van Spaendonck (Dutch, 1746–1822), Bouquet of Mixed Flowers with Butterfly, Beetle, and Ladybug, 1796, oil on white marble, 20 × 14 7/8 in. (50.8 × 37.8 cm). Private Collection

Although it is now apparent that many examples of still life paintings on stone were made, my database contained fewer than thirty such works, and I originally selected five to be in the show.[3] These included a marble panel entitled Bouquet of Mixed Flowers with Butterfly, Beetle, and Ladybug painted by Dutch painter Gerard van Spaendonck (1746–1822) in 1796 (fig. 2),[4] a trio of flower paintings on slate by the Roman painter Mario Nuzzi, known as Mario dei Fiori (1603–1673),[5] and a marble panel with an image of flowers and sweets on a marble tabletop by the Neapolitan artist Giuseppe Recco (1634–1695, fig. 3). In the end, none of them appeared in the show. Requests for the loans of the van Spaendonck and the Nuzzis were turned down.[6] The Recco is in a private collection in Mallorca, and I was never able to examine it personally and therefore, in the end, could not consider it for the exhibition.

Giuseppe Recco (Italian, 1634–1695), Still Life with Food and Flowers on a Marble Table, 17th century, oil on marble, 20 1/2 × 25 1/5 in. (52 × 64 cm). Private Collection. Photo © Claudio del Campo

It was the panel by Recco, however, that prompted me to think seriously about the unique role that material support could play in the depiction of still life. Recco’s rendering seemed a celebration of the variegated marble support. His signature at lower right floats beneath the fictional tabletop and thus deviates from the artist’s more typical practice. It is not depicted as if it were chiseled into the edge of the painted marble table, nor has he inscribed his initials into the rim of a painted marble surface or the roughened edge of a stone slab as he did in his canvas pictures. This signature, seemingly engraved in the stone panel itself, suggests a conscious reminder by the artist that the stone support itself had a presence in the physical world.

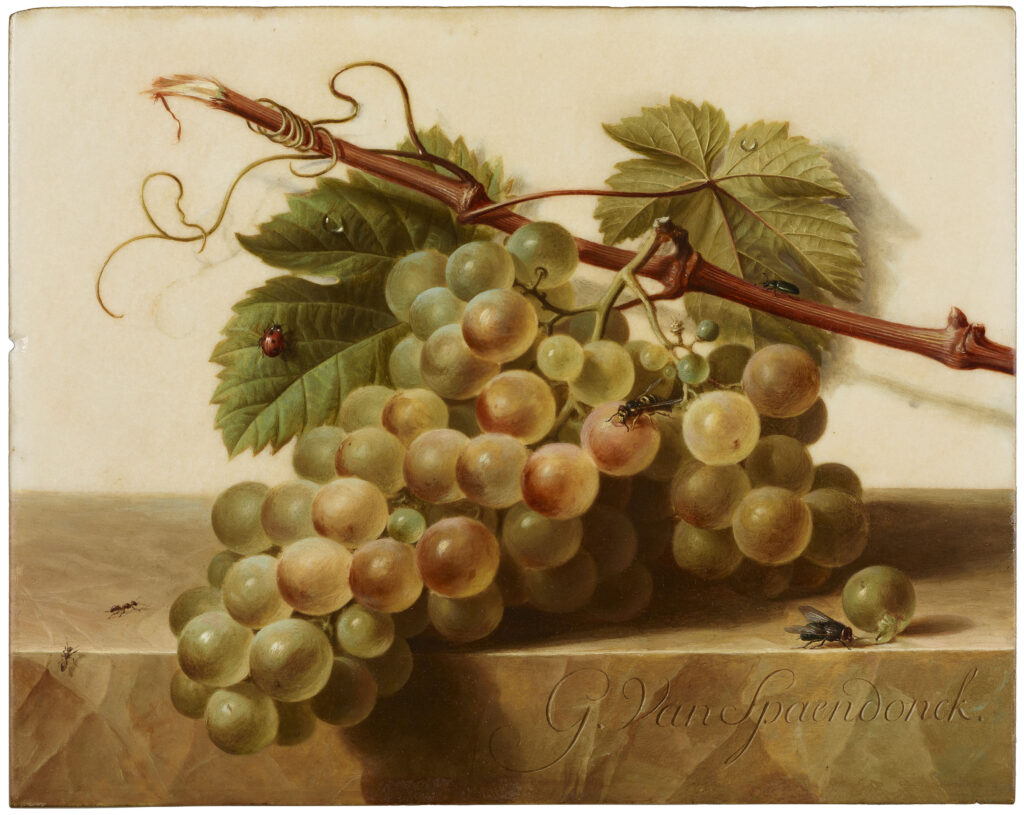

Gerard van Spaendonck (Dutch, 1746–1822), Grapes with Insects on a Marble Table Top, ca. 1791–1795, oil on white marble, 7 3/8 × 9 1/4 × 1/8 in. (18.7 × 23.5 × .3 cm). The Frick Collection, New York, Gift of Asbjorn R. Lunde, 2012, acc. no. 2012.1.01

My meditations on the issues raised by the use of stone supports for still life paintings were furthered by the opportunity to study the sole still life painting on stone that did appear in the exhibition. When the owner of the van Spaendonck Bouquet of Mixed Flowers with Butterfly, Beetle, and Ladybug declined to loan his picture, I was able to replace it with another marble painting by the same artist.[7] On a trip to New York during the period I was finalizing the list of paintings that would be in the show, I visited the Frick and was reminded of their small van Spaendonck on white marble (fig. 4), Grapes with Insects on a Marble Top (ca. 1791–1795), which I successfully secured for the show. It proved more than just a serendipitous addition to the exhibition, since this small marble panel illuminates a fascinating aspect of how stone supports interact with and confound the role of illusionism in still life paintings.

Still Lifes on Stone in the Context of the General Practice of Painting on Stone Supports

Attributed to Girolamo Macchietti (Italian, 1535–1592), Portrait of the Young Ferdinando de’ Medici, 1560s or 1570s, oil on red porphyry, 7 11/16 × 6 11/16 in. (19.5 × 17 cm). Private Collection

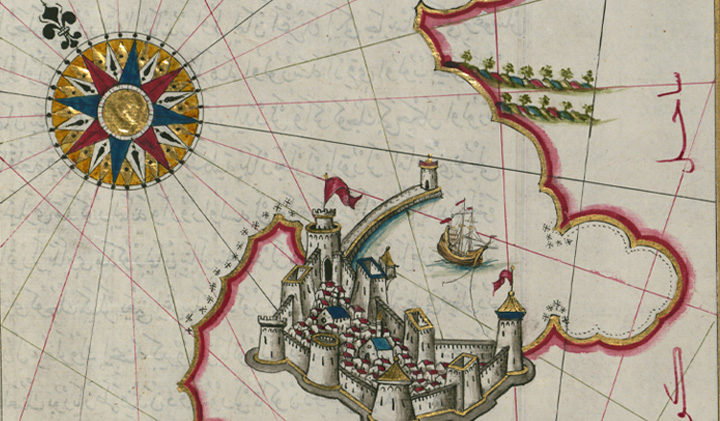

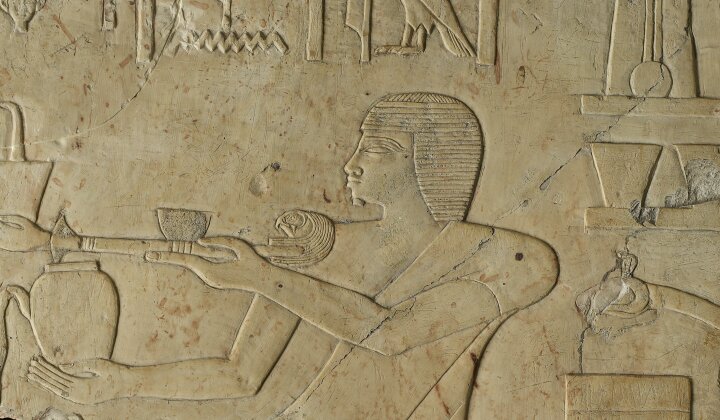

In order to clarify the specific issues that are raised by using stone for still life subjects, it is helpful to review the development and spread of the use of stone supports in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Painting on stone surfaces was initiated by Sebastiano del Piombo (ca. 1485–1547) and others in early to mid-sixteenth-century Rome. For those early users of stone, the material was important and often had symbolic significance. These individuals did not originally turn to the use of stone out of an appreciation for the beautiful and interesting visual qualities of the support. In fact, most early stone paintings were on slate, and artists usually covered the full stone surface with paint. In those rare early instances when they used colored stones or allowed the bare stone to show, as did the Florentine artist Girolamo Macchietti (1535–1592) in portraying the young Ferdinando I de’ Medici (1549–1609) before he became the grand duke of Tuscany (fig. 5), they did so to enhance the image’s meaning or to deepen the spiritual effect.[8] For Macchietti, the rare and costly red porphyry attested to the power and wealth of the Medici family. In the 1570s, in the region of Venice, Jacopo Bassano (ca. 1510‒1592) and his workshop seem to have been the first to routinely leave sections of black stone surfaces unpainted, using the bare stone’s intense darkness to enhance the effects of light penetrating deep shadow (fig. 6).[9] It is worth noting here that the Walters Art Museum owns a later work where using bare slate helps create impressive effects of light and shadow, Alessandro Turchi’s St. Peter and an Angel Appearing to St. Agatha in Prison, created in the 1620s (acc. no. 37.552). It is among the finest examples of his work on slate.[10]

Jacopo Bassano, Italian, c.1510–1592; Lamentation by Candlelight, 1570s; oil on slate with gilding; 11 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1/2 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Funds given by Opal and Arthur H. Meyer Jr.; Museum Purchase, by exchange 95:2021

In the 1590s, an important change occurred. Artists began using a larger variety of colored and patterned stones for their paintings and integrating the physical qualities of the stone support into their finished compositions. This is beautifully demonstrated by Cavaliere d’Arpino’s Perseus Rescuing Andromeda (fig. 1), where the artist used the blue of the lapis lazuli to represent both water and sky. He also responded to an existing crack in the panel, altering Andromeda’s pose that he had used in an earlier slate version of the painting (now in the collection of the Rhode Island School of Design) to align her right toes with the edge of the break.[11] He was able to do so by changing her pose so that her left rather than her right leg supported her weight, demonstrating how the physical characteristics of the stone guided his artistic choices.

The reasons that artists began using a wider range of types and colors of stone have not yet been fully investigated nor understood—they may include something as simple as the increasing availability of a greater variety of rocks. Grandduke Ferdinando I de’ Medici, for example, founded the Galleria dei Lavori (now known as the Opificio delle Pietre Dure) in Florence in 1588, seeking to focus the Medici workshops on the production of hardstone inlays and veneers. Individual workshops had already been producing impressive examples of stone inlay in the 1560s, but Ferdinando sought to consolidate the works into a grander, imperial production. Such an endeavor required importing stones such as lapis lazuli, jasper, Egyptian alabaster, amethyst, and various colored marbles.[12] The refurbishing of early Christian churches that followed Pope Sixtus V’s (1521‒1591) efforts at returning the city of Rome to its former splendor, as well as the preparations for the Jubilee year in 1600, may also have made more pieces of colored marble available.[13] Another motivation for selecting stones with rich veining and colorful striations may have stemmed from an intellectual change in the understanding of the relationship between the artist as creator and the natural world, including stones, which was the handiwork of God, the creator of all things.[14] Artists were now working in partnership with God as they fashioned images that incorporated elements of God’s creation into their own work.

When the physical appearance of the stone surface began to be incorporated into the image, the relationship of the paint and the support changed profoundly. Initially, the painted image and the support underneath it were discrete entities. This can be seen in the portrait of Ferdinando de’ Medici (fig. 5) where the painted head of the young duke can be easily considered as separate from its porphyry background and understood independently. In the late sixteenth century, however, the support came to be fully integrated with the artist’s painted creation into a collaborative whole. For example, in the double-sided representation of the Annunciation and Resurrection of Christ (fig. 7), Sigismondo Leyrer (1552/53–1639) relied upon the striations within the agate to guide his composition. These irregular concentric bands enhance the understanding of Gabriel’s heavenly origin and suggest the divine destination for the risen Christ.[15] Were the painted portion of the composition to be separated from the stone, it would lose the obvious reference to the divine realm of Gabriel and God the Father, and thus a significant element of its meaning.

Sigismondo Leyrer (German, 1552/53–1639), Annunciation (recto), 1594, oil on agate, 9 13/16 × 5 5/16 in. (25 × 13.5 cm). Real Monasterio de la Encarnación, Madrid Patrimonio Nacional, 00620358

In returning to the examination of van Spaendonck’s Grapes, one of three stone versions he made using a cluster of the fruit, we can witness a third significant change, a profound realignment of the relationship of depicted subject to material support where there is a fuller merging of the two. To restate this change, one can say that while in the 1590s the material support was part of the fictional image (for example, blue stone became blue sky or blue water), in the 1790s, in addition to reading the stone as part of the painted subject, one also experiences the actual physical stone as part of the three-dimensional world around it. The material affords the painting a new status in the physical world. In the 1590s, the material operates within the fictive world of the image; in the 1790s, the stone also exists within the actual world.[16]

In more fully examining van Spaendonck’s Grapes with Insects on a Marble Top (fig. 4), we can appreciate the naturalism of the depiction; the small scale of the picture has not diminished its exacting detail and strong adherence to visual fact. Ants climb up the side of the stone tabletop and vault themselves onto the horizontal surface while a ladybug navigates the veins of one leaf, perhaps in pursuit of the droplet of water suspended above. A beetle traverses the woody horizontal stem, and a fly has lit upon one of the reddish orbs. A second fly approaches a grape that has fallen onto the marble ledge in the foreground.

In recognizing this appealing display of carefully observed fruit, it is necessary to note that van Spaendonck specialized in floral rather than fruit still life, raising the question as to whether he approached the depiction of fruit still life differently from the manner in which he portrayed flowers. From 1780, van Spaendonck served as professor of flower painting at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, where his most important student was the renowned floral painter Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759–1840).[17] Most discussions of van Spaendonck’s production focus on his floral work and make little mention of the fruit still lifes. Even less attention has been paid to his production on stone. The catalogue raisonné of his work lists only three stone paintings, all painted on marble: Peaches and Grapes on a Marble Top, the floral still life on marble mentioned earlier (fig. 2), and A Branch of Grapes Suspended from a Shell-Shaped Hook.[18] The catalogue authors noted that the artist painted a second version of this last composition on marble, in horizontal rather than vertical format, that he presented at the Paris Salon of 1793 and which they indicated was lost. This could be the painting now in the Frick (fig. 4). The authors omitted another variant of the grapes attached to a wall, Still Life with Grapes (fig. 8) that had been in the Musée Fabre, Montpellier, until it was stolen from the museum in 1987.[19] Therefore, until now, Gerard van Spaendonck’s known painted marbles totaled only five. In July 2023, a sixth marble panel depicting a small bouquet of flowers resting on a dark stone ledge with a butterfly flying nearby was included in Sotheby’s London Old Master Paintings sale.[20]

Gerard van Spaendonck (Dutch, 1746–1822), Still Life with Grapes, 1791, oil on marble, 10 1/0 × 7 7/8 in. (26 × 20 cm). Formerly Musée Fabre, Montpellier, acc. no. 836-4-70 (stolen 1987)

It seems noteworthy that, in selecting subject matter to paint on a marble support, van Spaendonck portrayed flowers, his specialty, only twice (at least only two are currently known) yet depicted compositions with grapes four times. Of these, three focus on the grapes alone, although each is marked by a slightly different combination of insects. Furthermore, all three images that are limited to grape clusters include shadows cast by the grapes and grapevine on the white marble support. None of the other three paintings has such a shadow. The still life with grapes and peaches includes only shadows cast on the horizontal stone surface on which the fruit rests; no shadow graces the background wall. In depicting the spray of flowers on white marble (fig. 2), often cited for its accurate portrayal of contemporary tulips (particularly the large size of the blossoms and their variegated colors), van Spaendonck failed to indicate any shadow cast on the background wall. In the newly discovered flowers on a stone ledge, we can also note such an omission. One might observe, therefore, that when portraying subjects other than grapes on a white marble support, van Spaendonck made no attempt to firmly establish a spatial relationship between the objects portrayed and the white stone. It seems worthwhile, therefore, to ask whether the subject matter of grapes inspired a special approach.

The representation of a grape cluster occupies a significant place in the history of illusionistic painting. A foundational story told by Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE) concerning the practice of illusionism described a fifth-century BCE competition between the artists Zeuxis and Parrhasius. Zeuxis rendered grapes that were so lifelike they fooled birds who tried to eat them.[21] He was, nonetheless, outdone by Parrhasius who painted a curtain so realistically that Zeuxis himself was fooled into thinking it was a fabric drape that needed to be pushed aside. Although Zeuxis did not win the day, it is his portrayal of grapes that has been traditionally cited to denote the apogee of naturalism. One wonders if van Spaendonck was intentionally citing this celebrated myth of illusionism when he used marble surfaces for his representations of the fruit.

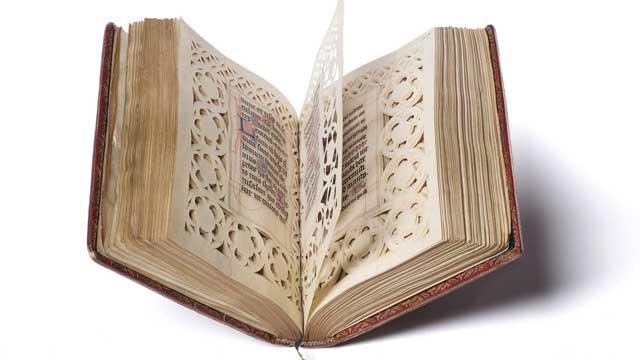

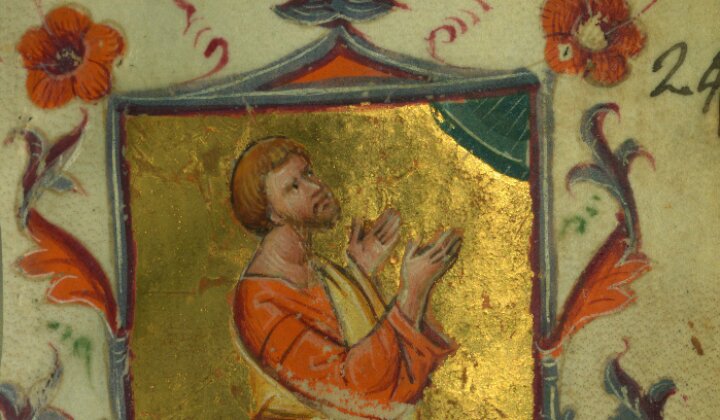

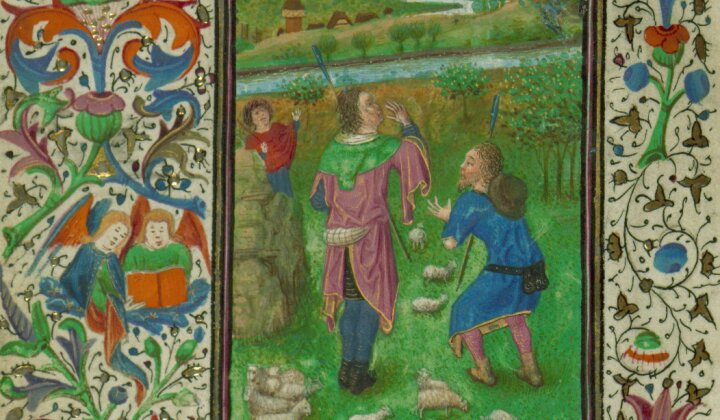

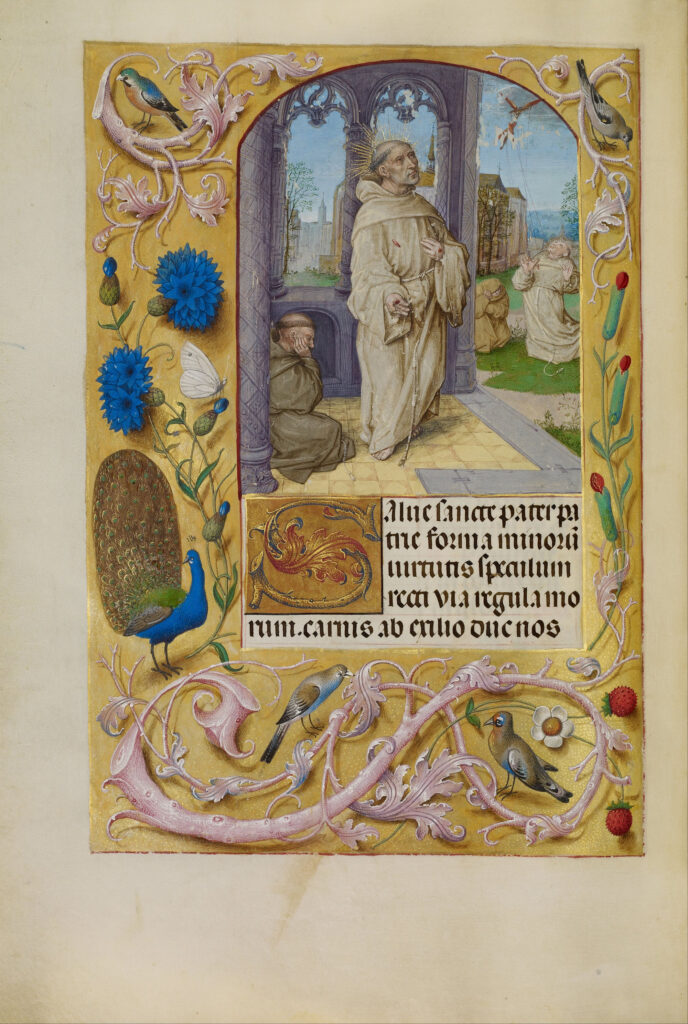

Master of the Lübeck Bible (Flemish, ca. 1485–1520), The Stigmatization of Saint Francis with Illusionistic Border from the Spinola Hours, ca. 1510–1520, tempera colors, gold, and ink, leaf: 9 1/8 × 6 9/16 in. (32.2 × 16.7 cm). J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 1983, Museum Purchase, acc. no. Ms. Ludwig IX 18 (83.ML.114), fol. 258v

Certainly van Spaendonck engaged with several aspects of fictive illusionism. He placed the grapes on an extremely tactile stone ledge, with variations in the coloration and texture. He also created the impression of a chiseled signature that could be read as having been chiseled into both the stone ledge and the stone support. The fictional and the real coincide in the background, where the cast shadow suggests both a marble background wall against which the grapes appear to lie as well as the surface of the marble support itself. Had the shadow been omitted, as it was in the floral spray, the white marble surface would be taken for an empty background. The shadow limits the fictive space of the representation and enhances the illusion of grapes lying on a stone ledge that abuts a wall of white stone. Van Spaendonck’s production also included works on vellum and paper, and one wonders if part of his inspiration may have derived from the tradition of illusionistic borders in Flemish manuscript painting (fig. 9), such as the illustrated page by the Master of the Lübeck Bible (ca. 1485–1520). There, one way of considering the use of such borders, spaces that Myra Orth has described as “exceptionally daring and assertive,”[22] is their service as mediational space between the completely fictional narrative illustration and the reality of the world of the reader. Although there are no gradations of illusionism in van Spaendonck’s case, such treatment of space establishes a different relationship between the grapes and the marble than exists between the viewer and the marble. By putting this image on stone, there is a surrender of illusionism to a certain degree since the viewer is now tasked with the job of differentiating between the illusionistic and the material, for they are in part fused.

Nicolas de Largillière (French, 1656–1746), Two Bunches of Grapes, 1677, oil on panel, 9 2/3 × 13 1/2 in. (24.5 × 34.5 cm). Fondation Custodia, Paris, 1949, acc. no. 6062

Van Spaendonck is hardly alone in choosing to focus a still life depiction on grapes, and inevitably the story of Zeuxis may have been the original inspiration for other artists as well. An example by Nicolas de Largillière (1656–1746) in the Fondation Custodia in Paris (fig. 10) is a wonderful study of both red and white grapes, painted illusionistically on a wood panel. But using a wood support for the background does not introduce any of the subtleties and intentional confusion that make the van Spaendonck painting such a rich image.

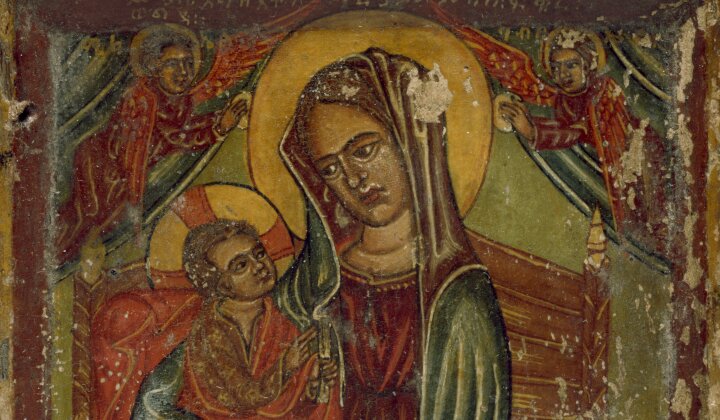

The Painting on Stone as Material Object—Earlier Examples

The same self-conscious approach to the physical presence of stone and its related properties that we find in van Spaendonck’s marble appears in several examples of paintings made on stone prior to the eighteenth century. The exhibition included three examples of the Annunciation painted on translucent stones (alabaster and agate), two of which comprised one side of a two-sided composition. They include the intriguing and quite wonderful painting by Sigismondo Leyrer (fig. 7) and a beautiful rendition by Antonio Tempesta (1555–1630) painted over one hundred years later.[23] As pointed out in the catalogue, the artists must have had in mind the notion that the perfect metaphor for Mary’s maintained virginity after giving birth was the passage of light through stone, an analogy that must go back at least to the twelfth century.[24] One can go further to say that this usage acknowledges the physical painting itself as a reference to Mary. Its existence in the physical world where light can penetrate the surface illustrates in a more vivid manner this most essential aspect of Mary’s exceptional nature. The panel itself, rather than what is depicted on it, becomes the vehicle for expressing Mary’s virginal status. The relationship of the material panel to what is depicted on the panel has changed.

Jacques Stella (French, 1596–1657), Christ Appearing to the Virgin, ca. 1643, oil on alabaster backed with slate, 11 3/16 × 16 1/8 in. (30 × 41 cm). Musée du Louvre, Paris, 1797, acc. no. 7967

A seventeenth-century painting now in the Louvre addresses this fusion of painted image and physical object in a most creative way. It is an octagonal alabaster depicting Christ Appearing to the Virgin, ca. 1643 (fig. 11),[25] painted by Jacques Stella (1596–1657), far and away the most creative user of stone surfaces for his painted works. Two other works by this artist demonstrate his creativity when he used other varieties of stone. In portraying the story of Judith in a painting now in the Galleria Borghese, he established a new narrative moment in the story of Holofernes’s decapitation where Judith seeks divine guidance prior to beheading the Assyrian general. Using a polished stone surface and large amounts of gold paint, Stella built the composition around a foreground candle, understanding that when the painting was seen under flickering candlelight, which would animate the highly reflective surface, the viewer would be invited into the scene and engage with the drama in an entirely new way.[26] In another of his pictures on stone, in a private European collection, he captured the Holy Family stopping at the end of the day en route to Egypt. The small picture is made up of at least seven pieces of the precious stone lapis lazuli, and a white area of calcite at the right of one of the pieces of lapis suggests the glow of the rising moon.[27]

But his most ingenious rendition on a stone support is the aforementioned Christ Appearing to the Virgin (fig. 11). Christ appears in a resplendent red robe before a field of alabaster, which was often used as a visual reference to the heavenly realm. Mary reaches out to embrace Jesus, stepping as she does so from a section painted dark gray to resemble slate, onto the alabaster. The area painted to look like slate, therefore, serves as a metaphor for the earthly realm, as contrasted with the heavenly space represented by the alabaster. However, Stella has gone beyond symbolic references. This painting, as is the case with many alabaster panels, was backed with slate for stability. Therefore, Stella not only differentiated between the earthly and the heavenly through his fictive depiction of the commonly used slate but also referred to the physical panel itself, suggesting he has peeled away the layer of alabaster to reveal the slate backing. In this way, he acknowledged that the painting is a tangible object that exists in the world of the viewer.

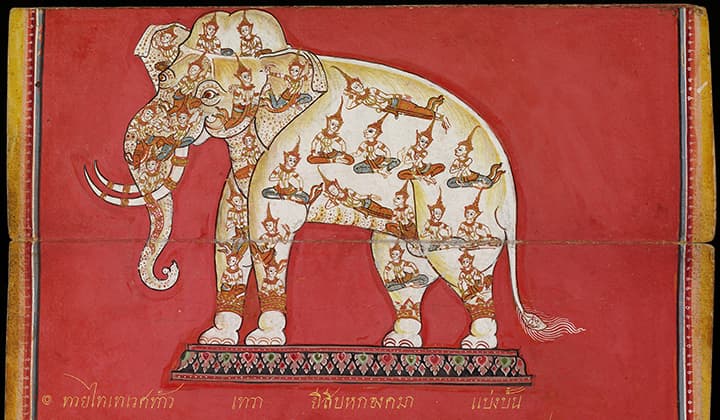

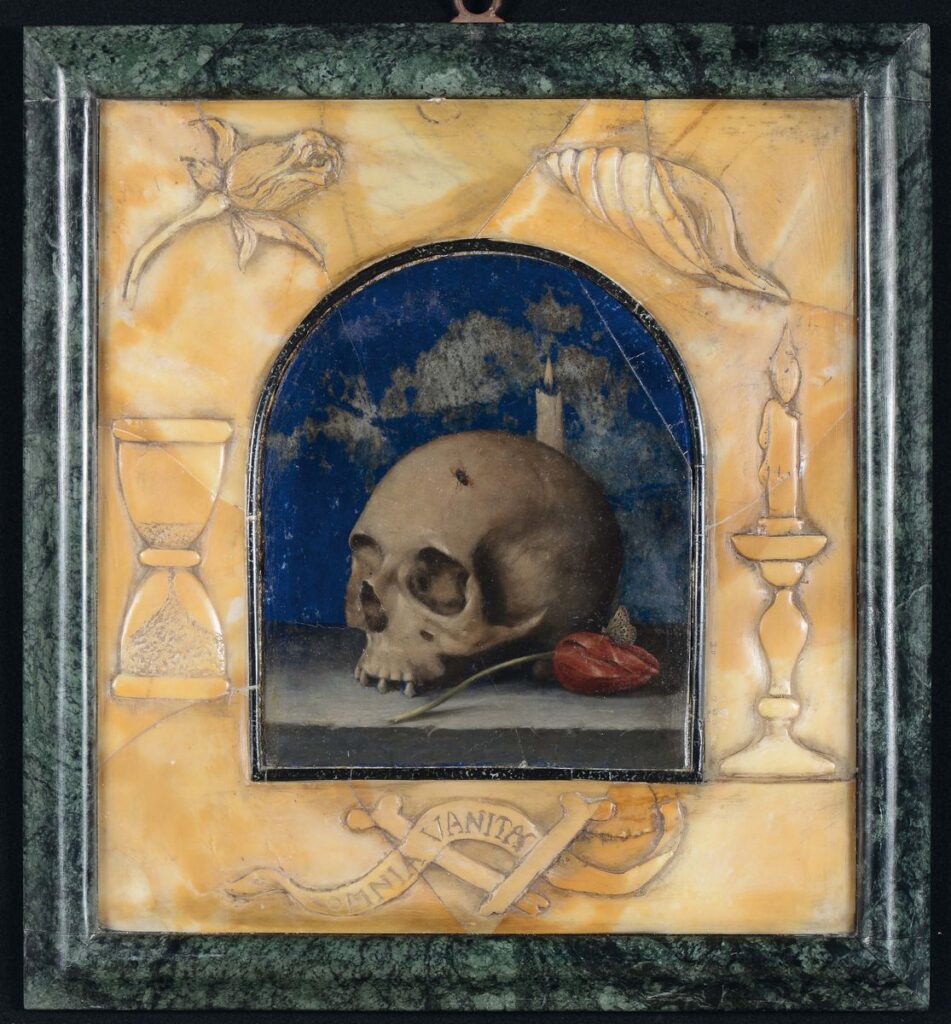

Jacopo Ligozzi (Italian, 1547–1627), Vanitas Still Life with a Fly, Skull, and Candle, and Butterfly Resting on a Tulip, early 17th century, oil on lapis lazuli, 8 1/2 × 7 1/4 in. (22 × 18 cm). Location Unknown

A somewhat different take on this duality, between what we might term “representation” on the one hand and “real presence” on the other, can be found in a Vanitas still life, one that reminds us of the transience of human life.[28]Attributed to the Florentine artist Jacopo Ligozzi (1547–1627), it is comprised of at least four pieces of lapis (fig. 12). It came to light in an Italian auction house in 2015. It is the only example I have encountered of a still life on this precious stone, and if considered carefully, it becomes one of the most potent reminders of the lures of the physical world. The subject is rather straightforward in terms of imagery we associate with meditations on death or the brevity of life—a skull, a butterfly, a closed tulip, a lit candle, and a fly that has come to rest on the front of the skull. What is different here is that the support is a material that potentially plays an integral role in the theme of the painting. Since it is painted on an expensive and rare material, the painting itself exemplifies the worldly riches that should be eschewed by the virtuous.[29] The physical panel, rather than what is depicted upon it, carries the message.

Returning to van Spaendonck’s Grapes with Insects on a Marble Top (fig. 4), it can now be appreciated as a complex image masquerading as a simple depiction of a bunch of grapes. In my initial introduction to the painting, I suggested that we are looking at a noteworthy change in the use of stone supports, perhaps a late eighteenth-century development. This would challenge the notion, put forth by John Spike in his important catalogue on seventeenth-century Italian still life painting, that over the course of the seventeenth century, there was an “irreversible descent of the still life genre into the realm of decoration.”[30] It seems, at least in the eighteenth century, that stone still lifes could challenge viewers to think closely about the physical object before them. This was not, however, only a product of the eighteenth century. As I just outlined, there were seventeenth-century examples of paintings on stone in which the artists intentionally referenced the existence of the stone panel within the tangible world of the viewer. We have also seen that this approach was not unique to still life but was used in religious narratives as well.

Nonetheless, still lifes in general are predicated on the illusion of the physicality of the objects displayed in them, therefore the introduction of a stone support brings new uncertainty as to what is physical object and what is illusionistic painting. That confusion changes the experience. As I have argued in the case of most paintings on stone, the sheer presence of the stone support changes everything. A perfectly serviceable portrait, when painted on stone, becomes a potent reminder of the power of memory; a biblical narrative, on durable stone, may also allude to the constancy of the Church and its teachings by continuing to adhere to the principles of the early Church in a time of challenge and turmoil. So it is with still life on stone—the material support changes the experience. In the case of the van Spaendonck, it underscores and enhances the illusionism, and at the very same time challenges the efficacy of the illusionism since its material merges with the objects of the everyday world. This may explain the experience of Erasmus, who in his Convivium religiosum (1522) described gardens with floral decorations painted on the stone walls: “Our pleasure is double when we compare a painted flower with a natural flower: In the latter we admire the art of nature; in the former we admire the painter’s genius.” Of course, such a comment could have been elicited by a still life on canvas or panel, but the fact that it was prompted by flowers depicted on a stone wall suggests he experienced those flowers in a more tangible way.[31]

Future Directions

I am only at the beginning of this study, and based on the very small database on which I have drawn, it is too early to draw definitive conclusions. I still have not fully integrated the role and influence of trompe l’oeil pictures. It is especially interesting to me that the painter who introduced the term trompe l’oeil (literally, “deceives the eye”), Louis Léopold Boilly (1761–1845), painted an arrangement of objects onto a real marble tabletop (fig. 13). He went beyond simply the intrusion of the tabletop into the viewer’s world and included several references to himself, such as his signature, a calling card with his address on it, and two self-portraits. These features, in Susan Siegfried’s words, “monitor the viewer’s awareness of the deception that he is perpetrating.”[32] The address contained on the calling card is especially evocative and carries the illusionism of the tabletop yet one step further—reminding the visitor of a world beyond that of the immediate environs of the picture. Boilly also used wooden tabletops to enhance the illusion, so in his case it is not just a function of using a stone support. It may not be possible, therefore, to see the van Spaendonck as part of a continuous line of development that begins with Sigismondo Leyrer’s Annunciation in 1594 and leads to the work of Boilly. Nonetheless, the small marble panel portraying a bunch of grapes on a fictional marble surface on view at the Frick offers an intriguing commentary on just how much the use of stone supports can both alter and enhance the experience of art. It is also a considerable distance from the way in which the viewer interacted with the lapis lazuli of Cavaliere d’Arpino’s Perseus Rescuing Andromeda.

Louis Léopold Boilly (French, 1761–1845), Trompe l’Oeil, ca. 1799–1804, oil on marble within an ebonised wood border, tondo: diam. 22 13/16 in. (58 cm). Private Collection, Canada

[1] On the painting, see Judith W. Mann, ed., Paintings on Stone: Science and the Sacred 1530–1800 (Munich: Hirmer Publishers, 2020), 138‒41, cat. 22, with relevant bibliography.

[2] Paintings on Stone: Science and the Sacred, 1530–1800 was on view at the Saint Louis Art Museum from February 20 until May 15, 2022. A related show, inspired by the exhibition in Saint Louis and featuring many of the same paintings, was shown at Galleria Borghese in Rome from October 24, 2022, until January 29, 2023, under the title Meraviglia senza Tempo. Pittura su pietra a Roma tra Cinquecento e Seicento (Marvels Beyond Time. Painting on Stone in Rome in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries).

[3] I now know that there were many more such paintings produced, although it is not possible at this point in our understanding of paintings on stone to hazard a guess as to how many there had been. Steffen Zierholz noted that over one hundred flower still life paintings by Giovanni Saglier on different sorts of marble were documented in the collection of Italian nobleman Vitaliano VI Borromeo when he died in 1690; see Steffen Zierholz, “A Natural History in Stone: Medusa’s Unruly Gaze on bardiglio grigio,” in Christine Göttler and Mia M. Mochizuki, eds., Landscape and Earth in Early Modernity: Picturing Unruly Nature (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2023), 209‒37, at 213n12. This is symptomatic of the many examples of this type of painting that have not yet been identified.

[4] Mann, Paintings on Stone, 242‒43, cat. 72.

[5] Mann, Paintings on Stone, 204‒207, cat. 54.

[6] Since the exhibition preparation was interrupted by the pandemic, I had decided to include all of my original choices for the exhibition in the catalogue, including those that did not appear in the exhibition, making it a more valuable reference tool on the subject of paintings on stone.

[7] Mann, Paintings on Stone, 242‒43, cat. 72.

[8] Mann, Paintings on Stone, 192‒93, no. 48.

[9] Mann, Paintings on Stone, 118‒19, cat. 11.

[10] Mann, Paintings on Stone, 284‒85, cat. 96.

[11] Mann, Paintings on Stone, 138‒41, cat. 21.

[12] On the Medici enterprise, see Annamaria Giusti in Wolfram Koeppe and Giusti, Art of the Royal Court: Treasures in Pietre Dure from the Palaces of Europe (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 16‒21.

[13] On the refurbishing of Rome, see Tod Marder, “Sixtus V and the Quirinal,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 37, no. 4 (1978): 283‒94, esp. n. 1, for a good list of sources.

[14] See Mann, Paintings on Stone, 30 and 33, nn. 70‒73.

[15] See Mann, Paintings on Stone, 186‒87, cat. 45.

[16] This is a very different interpretation than Norman Bryson’s discussion of the lack of human presence in still life, therefore suggesting that the world is pushed far away from the subjects in still life. The duality of subject and object inherent in still life is quite different from what happens with stone where it can be argued that there is a gradual merging of still life and the human world. See Norman Bryson, “Chardin and the Text of Still Life,” Critical Inquiry 15, no. 2 (1989): 227‒52, at 234.

[17] See the catalogue raisonné, Margriet van Boven and Sam Segal, eds., Gerard & Cornelis van Spaendonck: Twee Brabantse bloemenschilders in Parijs (Maarssen: Gary Schwartz, 1988); and Mann, Paintings on Stone, 242‒43, cat. 72, for additional bibliography.

[18] Van Boven and Segal, Gerard & Cornelis van Spaendonck, 102, no. 7. It is illustrated by a very poor black and white reproduction that did not warrant inclusion in this essay.

[19] Pierre Stépanoff, formerly curator at the Musée Fabre, Montpellier, and currently Director of the Musée de Picardie, Amiens, very kindly provided information on the painting, and verified that the picture has still not been recovered (email dated March 30, 2022).

[20] I wish to thank Cecilia Treves at Sotheby’s who so kindly brought these works to my attention and provided an early copy of the sale catalogue. There is also a small marble painting of grapes by a late eighteenth to early nineteenth-century French female artist, Iphigénie Decaux, a very rare occurrence among known paintings on stone surfaces. Only one other stone example by a female painter is known to me, a portrait attributed to Sofonisba Anguissola (died 1625) that was included in the 2022 exhibition.

[21] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 35, 65.

[22] Myra D. Orth, “What Goes Around: Borders and Frames in French Manuscripts,” Journal of the Walters Art Museum 54 (1996): 189–201, at 189.

[23] On the Tempesta, see Mann, Paintings on Stone, 276‒77, cat. 92.

[24] In the twelfth century, Abbot Suger at St. Denis famously invoked the idea of light passing through glass as a metaphor for Mary’s sustained purity. A source that may have had more relevance for Leyrer and Tempesta was the fourteenth-century Revelations of St. Bridget, where Christ said to her “I have assured the flesh without sin and lust, entering the womb of the Virgin just as the sun passes through a precious stone.” See Millard Meiss, “Light as Form and Symbol in Some 15th-Century Paintings,” Art Bulletin 27, no. 3 (1945): 175‒81; and Sarah Drummond, Divine Conception: The Art of the Annunciation (London: Unicorn, 2018), 87.

[25] Mann, Paintings on Stone, 260‒61, cat. 82. This subject, perhaps unfamiliar to modern readers, concerned a post-resurrection visit by Jesus to his mother, a medieval idea that saw a resurgence of popularity in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

[26] Mann, Paintings on Stone, 256‒57, cat. 80.

[27] Mann, Paintings on Stone, 252‒53, cat.78.

[28] Vanitas still lifes usually make reference to the passage of time, reminding viewers that their time on earth is limited. They often include elements that also refer to opulence and lavish material display, a reminder that one’s thoughts are best focused on virtue rather than earthly pleasures.

[29] Lapis lazuli was a very expensive material, primarily for two reasons. In the seventeenth century, its primary source deposits were in Afghanistan, requiring arduous and expensive shipping (later discoveries of the stone were made in Russia). Also, the lapis lazuli rock often included veins of golden pyrite and pure white calcite that intruded into areas of blue, therefore minimizing those areas of pure blue deposits.

[30] John T. Spike, Italian Still Life Paintings from Three Centuries (New York: National Academy of Design, 1983), 16.

[31] I wish to thank Dominique de Courcelles, Professor and Director of Research at the Research University, Paris, who brought that quotation to my attention as part of her own work on landscapes and gardens.

[32] Susan L. Siegfried, “Boilly and the Frame-up of ‘Trompe l’oeil,’” Oxford Art Journal 15, no. 2 (1992): 27–37, at 30.