Among the hundreds of Italian paintings Henry Walters acquired with his en bloc purchase of the famed Massarenti collection in Rome in 1902 is a little-known large tondo (circular work) painted in Florence in the last quarter of the fifteenth century (fig. 1).[1] Since its acquisition, the tondo has never been studied in depth, and it has for decades, if not a century, been in storage. It is, however, of exceptional interest, as it not only permits a clearer understanding of its anonymous maker’s career, but also invites some broader considerations about this object type, at once ubiquitous in the period and, as we will see, more multifaceted than typically recognized. Though it ultimately raises more questions than can be answered, a study of this panel expands our perspective on the typology of the tondo format and its role in a spectrum of devotional and ritual practices in later fifteenth-century Florence.

Master of the Fiesole Epiphany (Italian, active 1470‒1500), Madonna and Child with Saints John the Baptist, Sebastian, Margaret, and Mary Magdalen, late 1480s, tempera (?) on wood panel, 46 7/16 × 45 11/16 in. (118 × 117 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, acquired by Henry Walters with the Massarenti Collection, 1902, acc. no. 37.431

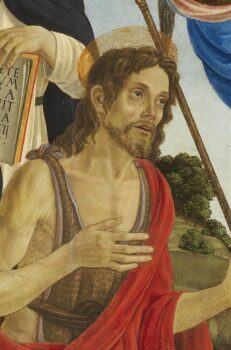

Measuring nearly four feet in diameter, the Walters tondo is dominated at the center by the Virgin, seated and looking down at the nude Christ Child, whom she holds in her arms. Affectionately, the child reaches for his mother’s cloak and looks up to meet her gaze. Standing to the left are Saints John the Baptist and Sebastian; to the right are Saints Mary Magdalen and Margaret. Each is identifiable by their most typical attributes: John with his reed cross, Sebastian with an arrow in his neck, Margaret with her dragon (barely visible at her waist), and the Magdalen with her jar of ointment. The group is situated beneath a box-like stone stable, topped by empty coffers thatched with hay. Behind, a landscape of lush, green hills is silhouetted against a golden horizon. Despite previous reports that the panel was trimmed, its shape is original.[2] Indeed, the semicircular arrangement of the saints, tunnel-like perspective of the stable, and the Virgin’s tapered, mandorla-shaped body are all tailored to the tondo format.

The tondo’s scholarly neglect can be explained by the fact that it long eluded a firm attribution. After initial attributions to the schools of Domenico Ghirlandaio, Sandro Botticelli, and Filippino Lippi, Federico Zeri, in his 1976 catalogue of the museum’s Italian paintings, assigned it to an anonymous Florentine of about 1480 “in a milieu not far from that of the young Raffaellino del Garbo.”[3] The present attribution was arrived at in 1984, when Everett Fahy, in an unpublished opinion recorded at the Frick Art Reference Library, assigned it to the so-called Master of the Fiesole Epiphany, an anonymous Florentine active in the last quarter of the fifteenth century.[4] Fahy’s idea was independently corroborated when Lisa Venturini examined the picture in storage in 1996[5] and has more recently been confirmed by several other scholars.[6] It is not, however, entirely straightforward, since the body of work assigned to this artist and forming the foundation of the attribution is not entirely homogeneous. Among the over one hundred paintings currently given this attribution,[7] many bear no more than a passing resemblance to the eponymous picture (fig. 2), raising the question of whether we are indeed dealing with an individual, verifiable “master” when considering the group as a whole. Therefore, before considering the attribution, it is worth revisiting the corpus and putting some order to this supposed artist’s catalogue.

Master of the Fiesole Epiphany, Adoration of the Magi with Saints Francis, Paul, and John the Baptist, ca. 1490, tempera (?) on panel, 127 × 57 in. (325 × 145 cm). Chiesa di San Francesco, Fiesole. Peter Horree / Alamy Stock Photo

Part I: The Artist

Master of the Fiesole Epiphany, Coronation of the Virgin, ca. 1490, tempera (?) on panel, 60 5/8 × 36 in. (154 × 92 cm). Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, inv. 1890 n. 490; Photo courtesy Bridgeman Images

A relatively recent entry in the literature on Florentine Renaissance painting, the name “Master of the Fiesole Epiphany” was first coined in 1967 by Everett Fahy to refer to the author of a large altarpiece (fig. 2), originally at the Convento delle Murate, Florence, but since 1907 at San Francesco in Fiesole, in the Florentine hills.[8] This rather unusual depiction of the Adoration of the Magi (the Epiphany), in which the Christ Child is encircled by the three kings and three saints, must have been painted soon after 1487; the background includes a giraffe, an animal unknown in Florentine painting until that year, when the Sultan of Egypt sent one to Lorenzo the Magnificent as a diplomatic gift.[9] Adopting an observation Odoardo Giglioli made in 1906, Fahy connected the Epiphany to a Coronation of the Virgin at the Accademia in Florence (fig. 3), to which it is indeed stylistically identical.[10] Around both pictures he grouped a large number of domestic devotional panels, most depicting the Adoration of the Child.[11] Because some of these had previously been assigned to Jacopo del Sellaio (ca. 1441–1493), Fahy wondered if his Fiesole Master might be identifiable with Filippo di Giuliano di Matteo (1449–1503), Sellaio’s longtime business partner, whose documented works remain unidentified.[12]

Master of the Fiesole Epiphany, Volto Santo di Lucca with Saints Vincent Ferrer, John the Baptist, Mark, and Antoninus, ca. 1481, tempera and oil (?) on panel, 72 3/4 × 79 3/4 in. (186.1 × 203.6 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of The Ahmanson Foundation, acc. no. M.91.242

Though entirely speculative (as Fahy himself acknowledged), the Filippo di Giuliano hypothesis has occasionally been endorsed, most notably by Anna Padoa Rizzo.[13] Writing in 1989, she furnished additional details about Filippo’s life, noting some intriguing, if ultimately inconclusive, correspondences with the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany’s oeuvre as it was then understood. More importantly, she expanded the painter’s catalogue with the attribution to him of the spectacular Volto Santo with Saints (fig. 4), originally on the choir screen of San Marco, Florence, where it was described by Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) and erroneously attributed to Cosimo Rosselli (1439–1507). In 1992 Nicoletta Pons made another important addition to the artist’s oeuvre: the lively Dream of Saint Martin (fig. 5) frescoed at the Oratorio dei Buonomini, Florence.[14] Part of a larger campaign headed by Domenico Ghirlandaio in 1478–1479,[15] the fresco importantly indicates that, at this point at least, the painter belonged to Ghirlandaio’s extensive team of associates.

Master of the Fiesole Epiphany, Dream of Saint Martin, 1478‒1479, fresco, approx. 59 × 60 in. (150 × 180 cm). Oratorio dei Buonomini di San Martino, Florence

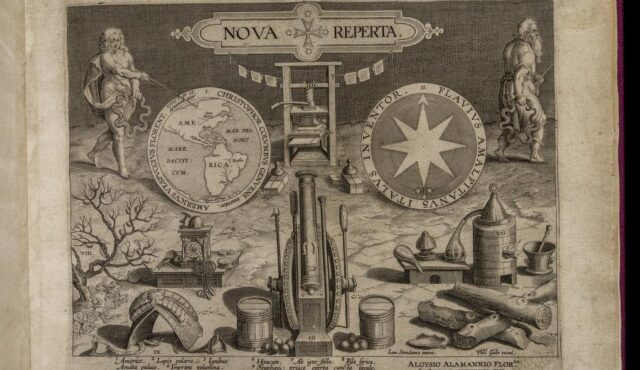

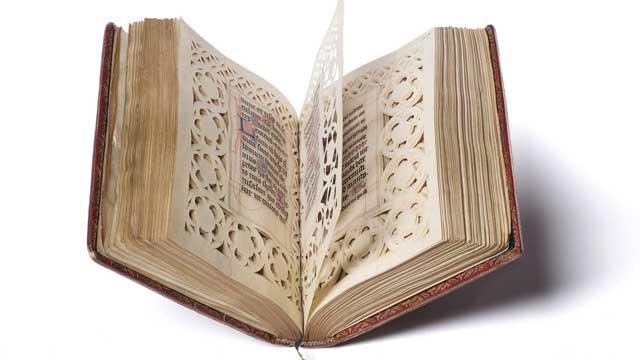

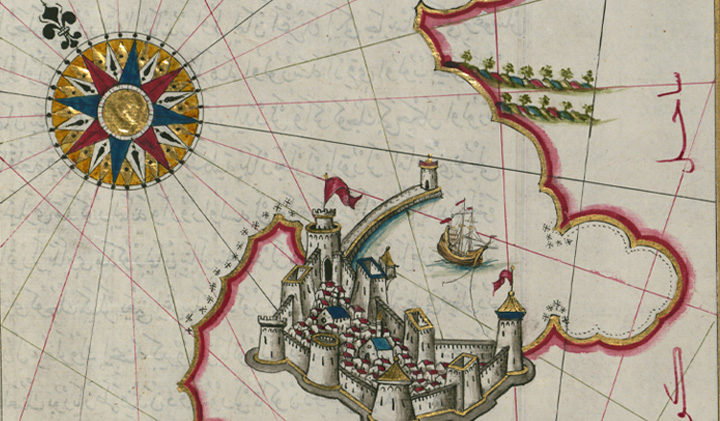

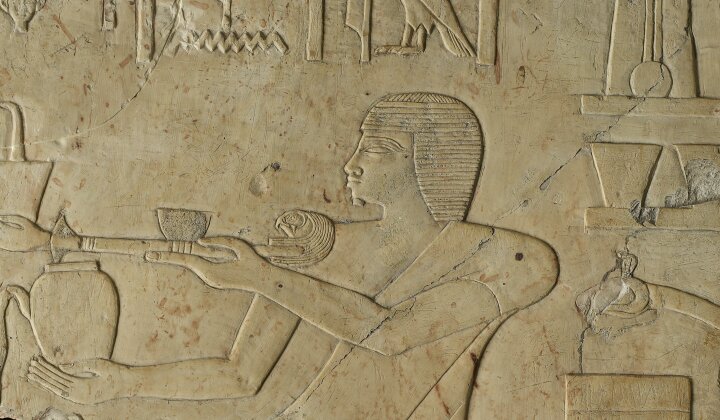

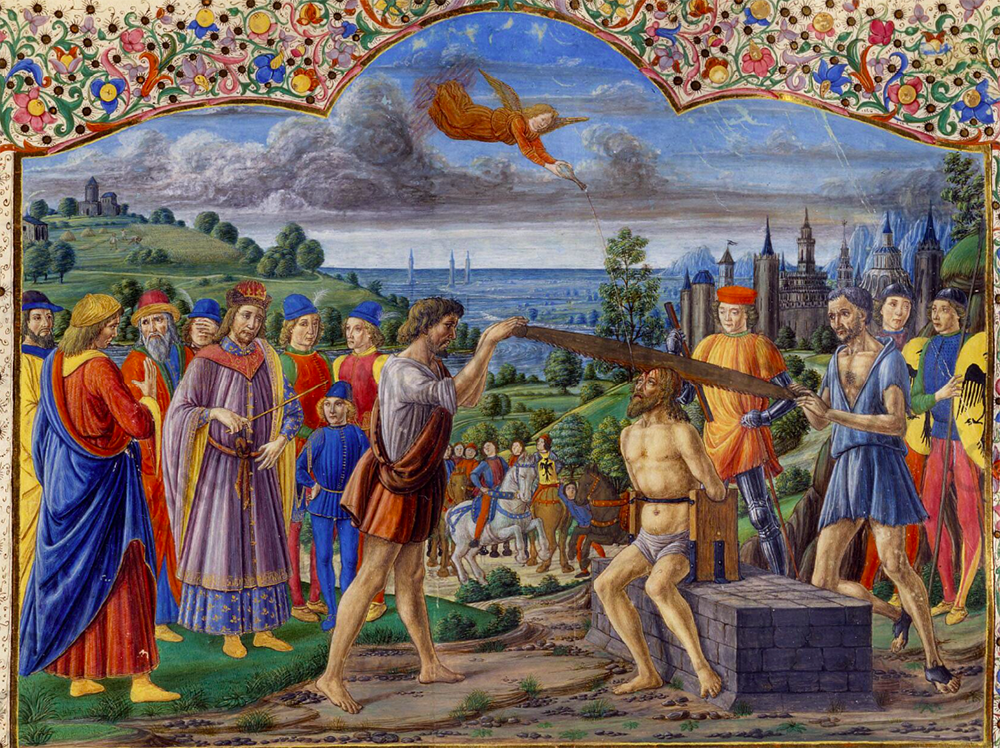

The Master’s close affiliation with Ghirlandaio is confirmed by his Volto Santo, which was conceived as a counterpart to an altarpiece by the more famous painter on the adjacent altar of S. Marco’s choir screen.[16] It is also supported by the Master’s much overlooked—in fact practically unknown—activity in the field of manuscript illumination. In 1474 he painted two miniatures in a choir book for Florence Cathedral,[17] and in 1477–1478 he contributed a dozen miniatures, all of astoundingly high quality, to Federico da Montefeltro’s extraordinary two-volume Bible (fig. 6).[18] In each of these, the figure types, drapery patterns, and landscapes are virtual reductions of those in the Dream of Saint Martin, Fiesole Epiphany, and Volto Santo; further, in technique and style, they are very close to the latter’s dismembered predella, or base. The decorations in both manuscripts were overseen by Francesco d’Antonio del Chierico (1433–1484), one of the most distinguished Florentine miniaturists of the day. Probably to expedite production, Francesco subcontracted many pages to talented younger colleagues, several of whom, like Francesco himself, had personal and professional ties to the Ghirlandaio family.[19] The Ghirlandaio brothers might have even served as additional collaborators.[20] Given the importance of these manuscripts—and especially of Federico da Montefeltro’s Bible, one of the most illustrious pictorial undertakings of the late fifteenth century—the illuminations should be held as key moments in Master of the Fiesole Epiphany’s trajectory and potential aids in his identification. His identity might eventually be found in this network—that of Ghirlandaio & co. in the 1470s—instead of, as per the outstanding hypothesis, that of Jacopo del Sellaio.[21] It is here worth remembering that aside from some mistaken past attributions or shared motifs, there is no concrete evidence linking the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany to Sellaio’s bottega (workshop) or to support the traditional identification with Filippo di Giuliano.[22]

Master of the Fiesole Epiphany, Supplication of Isaiah, 1478, tempera on vellum. Vatican Library, Vatican City, acc. no. Urb.lat.2, fol. 68r

To be sure, this core group of pictures (figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) constitutes a homogeneous corpus. Without a shadow of a doubt, it represents the output of a skilled, versatile painter whose rich coloristic effects and proficiency in both small- and large-scale painting were recognized by artists and patrons alike, and for whom the name “the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany” is indeed appropriate. As Susan Caroselli has aptly described in her discussion of the Volto Santo, his style is defined by its “strong contours and a bright, saturated palette…compositions in which many elements are carefully arranged to achieve a balance, if not an outright symmetry,” figures that are “well-proportioned, the flesh and the underlying bone structure being finely modeled with light and shadow…showing a luminosity equal to the finest modeling by Domenico Ghirlandaio,” and, most distinctively, draperies “arranged in heavy, rounded folds, flattening onto the ground, often in a peculiar oval arrangement over a knee or leg.”[23] These features can be clearly discerned in each of the works described above, as well as a handful of others enumerated in an appendix at the end of this essay.

Master of 1493 (Italian, active ca. 1480‒1500), Madonna and Child with an Angel and Saint Benedict, late 1480s‒early 1490s, panel, 27 × 17 in. (69 × 44 cm). Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon, acc. no. M.I.580

Master of 1493, Marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria with Saints John the Baptist, Louis of Toulouse, and Peter; lunette: God the Father, mid- to late 1480s, panel, 22 1/4 × 11 13/16 in. (56.5 × 30 cm). Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille, acc. no. 804

Master of 1493, Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John and Saint Peter Martyr, 1490s, panel, 30 x 17 in. (75.8 x 44 cm). The Courtauld, Samuel Courtauld Trust, London, acc. no. P.1966.GP.252

They do not, however, appear in many of the other works assigned to the painter. Most notably, they are absent from most of the small-scale devotional pictures gathered under his name (see, for example, figs. 7, 8, and 9), as well as some dated works, such as the Lanfredini-Tommasi spalliere (wainscot panels) of 1485,[24] the Last Supper at Santi Girolamo e Francesco alla Costa dated 1488, and the altarpiece from San Matteo in Arcetri dated 1493 (fig. 10).[25] Far from the solid, plastic vision of the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany, these paintings are instead soft, flat, and linear, showing a flimsier articulation of contour (especially in the hands), a brusquer application of paint, and a less expressive figural repertory indebted to Ghirlandaio, Perugino, and Bartolomeo di Giovanni (as opposed to Verrocchio or Cosimo Rosselli, whose styles are most clearly reflected in the Fiesole Master’s). Since these paintings reflect neither the quality nor style of the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany—but are nevertheless homogeneous among themselves—I believe they should be reassigned to a distinct personality. I propose calling their author the Master of 1493 after the date on the Arcetri altarpiece and urge future studies to consider these corpora separately when searching for names in the Florentine archives. It might also be wise to consider the great mobility that permeated the Florentine workshops at the close of the fifteenth century. In 1490, for example, Sellaio and Filippo di Giuliano took on a third partner, Zanobi di Giovanni, whose extant output, like Filippo’s, remains unidentified. A dense network of artists in compagnia (partnership)—working in the same physical space but not necessarily in the same style—might help in explaining the situation and the earlier confusion among these various painters.[26]

Master of 1493, Madonna and Child with Saints Matthew, Francis of Assisi, Louis of Toulouse and Clare, dated 1493, panel, 62 × 56 in. (160 × 143 cm). Museo del Cenacolo di Andrea del Sarto, Florence, inv. 1890 n. 3453

Until such an archival campaign can be undertaken, we can return to the Walters tondo, which can help in defining the “true” Master of the Fiesole Epiphany more clearly. For indeed, though its attribution has never been explained or justified, it is certainly compatible with his most typical pictures. For one, the smiling, doll-like figures are the same as those in the Epiphany itself, the Virgin being nearly identical in the two, showing the same heavy eyelids, gentle smile and broad, pleated drapery folds. The Volto Santo is equally close, presenting a comparably harsh chiaroscuro—the figures are bathed in such strong contrasts of light and dark that they appear to be made of polished wood—and a figure of Saint John the Baptist whose rapturous gaze is akin to that of the tondo’s Magdalen (figs. 11a and 11b). These fixed, wide-eyed expressions further appear in the two startling Pietàs recently assigned to the painter by Emanuele Zappasodi (e.g., fig. 12),[27] as well as an untraced Saint Humilitas here proposed as his work (fig. 13);[28] viewed together, these works further clarify the painter’s most typical traits and establish his authorship of the Walters tondo.

Master of the Fiesole Epiphany, Pietà, ca. 1485, tempera and oil on panel, 31 1/2 × 20 5/6 in. (80 × 51 cm). Galerie G. Sarti, Paris

Like the bulk of the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany’s production, the tondo probably dates to the 1480s. Compared to earlier works like the illuminations in the Montefeltro Bible (documented to 1476–1478) or the Dream of Saint Martin (1478–1479), its handling is broader and it shows a conventionalization of the earlier figure types much like in the Fiesole Epiphany. Given the latter is firmly dated to after 1487, the tondo can be dated similarly to the end of the decade. Usefully, the date highlights once again the vast stylistic and qualitative gulf between the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany and his distinct contemporary, the Master of 1493. Since the tondo’s style is irreconcilable with paintings with which it is more or less contemporary—the Last Supper of 1488 and Arcetri altarpiece of 1493 (figs. 14a and 14b)—it ultimately underscores the distinction between the two personalities, enabling a sharper vision of both.

Master of the Fiesole Epiphany, Saint Humilitas, ca. 1480‒1485, panel, dimensions unrecorded. Present whereabouts unknown

Part II: The Object

Beyond its complex attribution history, the Walters tondo should also be understood within the context of its format. In fact, there are numerous aspects of the work that are at odds with the vast majority of extant Florentine tondi. For one, while it is a great deal smaller than the largest-known tondo, Botticelli’s now-destroyed Madonna of the Candelabra formerly in Berlin (75 in. [192 cm]), it is still bigger than most of the extant examples, which typically average about 33 in. (80–85 cm).[29] Moreover, its visual impact is significantly amplified because of the composition, especially the Madonna, who is larger than life and seemingly swelling forward into the viewer’s space. With the now-lost original frame likely bringing its original diameter to at least six feet (the present frame is modern but nevertheless conveys some idea of the original), the tondo must have dominated the space in which it was originally installed.

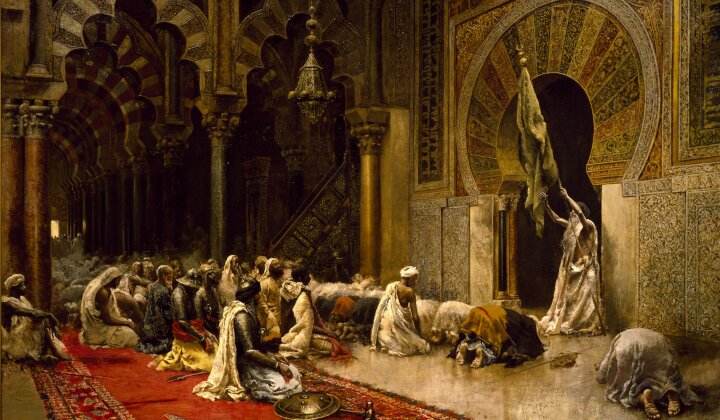

But what kind of space was this? One of the most popular image formats in Renaissance Tuscany, tondi were most often found in the domestic sphere.[30] They were typically hung high on the walls of bedrooms (camere) and viewed from below—a viewpoint the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany seems to have taken into consideration with the warped, sotto di sù (from below to above) view of the stable’s coffered ceiling and the Madonna’s downward glance. Tondi could also, however, be found in civic buildings. Botticelli’s famous Madonna of the Pomegranate (Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence) is one example, having been commissioned in 1487 for the audience hall of the Magistrato dei Massai della Camera in Florence’s Palazzo del Podestà.[31]

Sandro Botticelli (Italian, 1444/45‒1510), Madonna and Child with Eight Angels (Raczyński Tondo), late 1470s, tempera on panel, diam. 53 in. (136 cm). Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, acc. no. 102A. Credit: Berlin State Museums, Gemäldegalerie / Dietmar Gunne Public Domain Mark 1.0

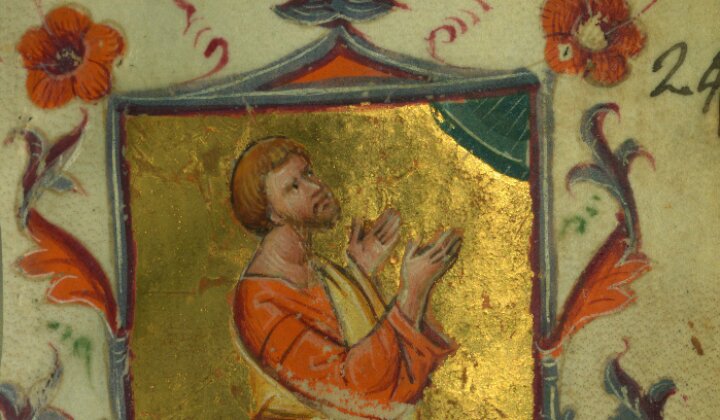

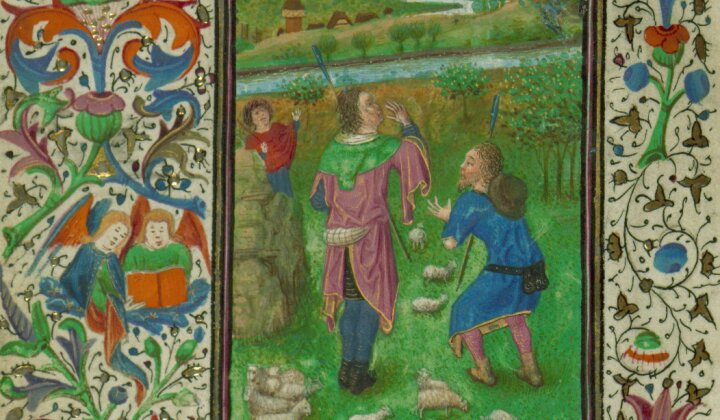

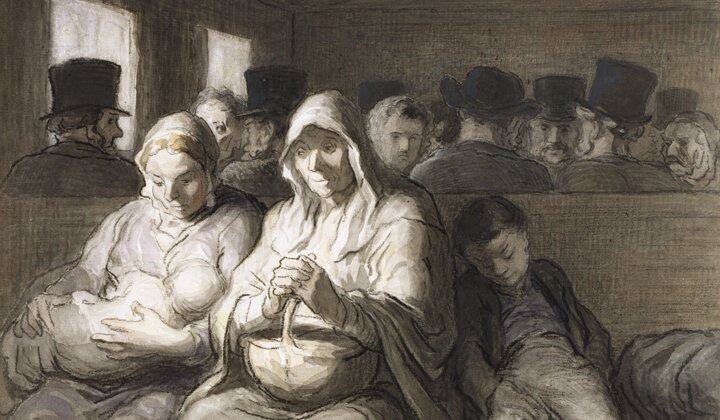

Less frequent were tondi in religious settings. In her exhaustive study on the object type, Roberta Olson cites only a few examples, all either frescoes or sculptures; most were intended for spaces that either had some sort of dual domestic function, such as a vestiary or dormitory, or as parts of large stone funerary ensembles, as is the case with sculpted tondi.[32] Tondi do not seem to have been used as altarpieces, though Vasari may allude to an example in his Life of Botticelli: “in San Francesco outside the Porta San Miniato, in a tondo, is a Madonna with some angels the size of life, held to be a very beautiful work.”[33] About thirty years later, the chronicler Francesco Bocchi described this tondo with more specificity, writing “in a chapel on the right wall [of the nave of San Francesco al Monte] one sees, by the hand of Sandro Botticelli, a very beautiful tondo in which is painted the Madonna with the child in her arms, surrounded by beautiful singing angels.”[34] In 1908 Herbert Horne identified this picture with the artist’s so-called Raczyński tondo (fig. 15) and interpreted Vasari’s testimony as indicative of the work’s original location.[35] While some scholars have accepted the hypothesis,[36] it is worth remembering that Vasari was writing nearly eighty years after the tondo’s completion, and the tondo could have conceivably been moved to the church from another location.[37] At the same time, even if the tondo was not conceived for San Francesco, it would be just as telling that it was repurposed as a church decoration less than a century after its creation. The circumstance suggests that sometimes, contrary to popular belief, freestanding painted tondi might have been suitable, if ultimately rare, image types in chapels and other ritual spaces.[38]

Master of Memphis (Bernardo di Leonardo? Italian, active ca. 1490‒1520), Madonna and Child with Saints Mary Magdalen and Catherine of Alexandria, ca. 1505, panel, diam. 45 in. (114.7 cm). Museo Soumaya, Mexico City, acc. no. 53847

Raffaellino del Garbo (Italian, ca. 1470–after 1527), Madonna and Child with Saints Mary Magdalen and Catherine, ca. 1498–1500, tempera on canvas, transferred from wood, diam. 50 in. (128 cm). National Gallery, London, acc. no. NG4903

Ridolfo Ghirlandaio (Italian 1483–1561), Madonna and Child with Saints Nicholas of Tolentino, John the Baptist, an Evangelist, and Saint Jerome, ca. 1505, oil on canvas, transferred to panel, diam. 35 in. (88.9 cm). Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte, NC, gift of Mr. Samuel H. Kress, acc. no. 43.1

Vincenzo Frediani (Italian, 1458–1505), Madonna and Child with Saints Michael, Jerome, Ambrose (?), and Catherine of Alexandria, ca. 1485–1488, panel, diam. 14 in. (38 cm). Present whereabouts unknown

Luca Signorelli (Italian, ca. 1441 or 1450–1523), Madonna and Child with Saints Michael, Vincent of Saragossa, Margaret of Cortona, and Mark, ca. 1510–1515, panel, diam. 57 in. (146 cm). Accademia Etrusca, Cortona

Accepting the possibility that the Botticelli originates from a sacred space, it is worth asking if the Walters tondo might also come from such a space. In fact, its unusual iconography seems to recommend this hypothesis. Tondi most frequently depict the Madonna and Child flanked by angels and/or the little Saint John or otherwise some variation of the Nativity or the Adoration of the Child, adopting an especially intimate tone to reflect the objects’ common destination in a domestic interior.[39] The Walters tondo, however, shows the Virgin and Child surrounded by multiple saints, an image type commonly known as a sacra conversazione and typically associated with altarpieces.[40] When tondi adopt this formula, they tend to include only two saints, usually the namesakes of the individual(s) who commissioned the work or the dedicatees of a familial alliance or lineage (figs. 16–17).[41] Other examples in which four saints appear include a tondo from about 1505 by Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio (fig. 18); here, however, the figures are all full-length, in an open landscape, and significantly smaller in relation to the picture field. Likewise, in an example by the Lucchese painter Vincenzo Frediani from the late 1480s (fig. 19), the figures are even smaller, and the entire object is essentially miniature. Seemingly intended for close, individual looking, the Frediani is best compared to several other diminutive tondi whose exact functions have yet to be determined.[42] Another sacra conversazione tondo from about 1510–1515, by Luca Signorelli, is perhaps most similar to the Walters tondo in its size and the number of figures (fig. 20). But it, too, presents important differences in that its iconography is strictly civic. Destined for the Palazzo dei Priori in Signorelli’s native Cortona, it shows the city’s four patron saints supplicating to the Madonna for the city’s protection, rather than, as in the Walters tondo, presenting her to the viewer.[43]

Jacopo del Sellaio (Italian, ca. 1441–1493), Madonna and Child with Saints Lawrence, Frediano, Peter, and Jerome, after 1486, panel, 59 × 58 in. (152 × 148 cm). Present whereabouts unknown

The sacra conversazione as it appears in the Walters panel—the large, seated Virgin at the forefront of the composition encircled by four diminutive standing saints—is, as far as I am aware, unique among late fifteenth-century Tuscan tondi. Its closest visual parallels are instead with altarpieces, especially those that use a compositional type devised in the early Quattrocento by Fra Angelico, Domenico Veneziano, and Filippo Lippi, promoted later in the century by, among others, Neri di Bicci,[44] Domenico di Michelino, the Master of San Miniato, and Francesco Botticini. An especially compelling comparison is an altarpiece of about 1486 by Jacopo del Sellaio (fig. 21):[45] like the tondo, it shows the figures hierarchically scaled—the Virgin is twice as large as the saints around her—and the saints projected inward toward her throne, as if to keep the spectator’s attention on her and the Christ Child. The similarities between these are, in fact, so strong that it is difficult to imagine a contemporary viewer looking at the tondo and not making a similar visual association, if not with the Sellaio than one of the many other altarpieces comparable in format. Since it ultimately exploits a type of didactic, presentational arrangement typically reserved for altarpieces, it may be worth asking if the Walters tondo might have had a similar function, if not as an altarpiece per se then as the devotional focus in a ritual space.

Jacopo del Sellaio, Madonna and Child with Two Angels, Saint Peter Martyr, and Tobit, ca. 1480, panel, diam. 32 in. (82 cm). Museo del Bigallo, Florence, acc. no. 18

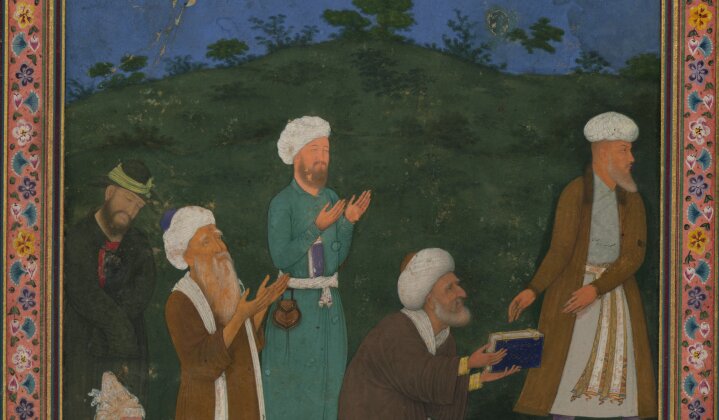

The premises of a confraternity (lay religious brotherhood) offers a tempting—if necessarily speculative—destination for the Walters tondo. Recent research has demonstrated that the confraternity spaces of Renaissance Florence were home to vast arrays of objects including several genres of painting today often over-emphatically connected to the domestic sphere, for instance wainscot panels (spalliere) and small-scale tabernacles (anconette or colmi da camera).[46] Confraternities also invariably commissioned altarpieces, not only for the chapels they leased in churches but also for the oratories adjoining their meeting rooms.[47] Confraternal tondi remain an uninvestigated phenomenon, but at least one survives on the premises of the Florentine confraternity for which it was made. At the Compagnia di Santa Maria della Misericordia (also the Compagnia del Bigallo) is a modestly sized tondo, from about 1480 and still in its original frame, by Jacopo del Sellaio (fig. 22).[48] Like the Walters example, the Bigallo tondo presents a Madonna and Child flanked by saints, this time the brotherhood’s two patrons, Saint Peter Martyr and Tobit. Behind them are two angels parting a gilded baldachin (canopy). Though the figures are here at full-length, Sellaio’s composition deploys some of the same visual distortions seen in the Walters tondo, such as the almond-shaped contours of the Virgin’s body, which makes it seem as if she swells toward the spectator. Evoking the distortions produced by a convex mirror,[49] this effect is furthered by the concave arrangement of the subsidiary figures around her. Furthermore, the group is contained within a surrounding framing device, in this case a gold baldachin rather than the humble stable in the Walters example.

Unidentified Lucchese painter, Saint Francis with Worshippers, mid- to late 1490s, panel, diam. 74 in. (189 cm). Museo Nazionale di Villa Guinigi, Lucca, acc. no. 325

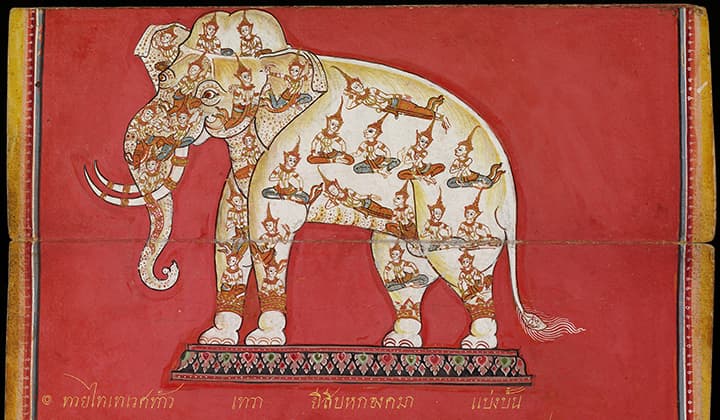

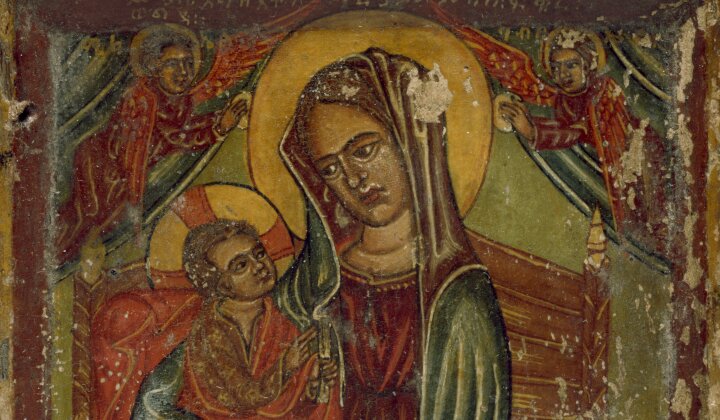

Another tondo almost certainly from a confraternity space is the monumental panel—in fact the largest extant tondo—at the Museo Nazionale di Villa Guinigi in Lucca (fig. 23).[50] Towering at over six feet in height, it depicts Saint Francis of Assisi surrounded by worshippers, men at the left and women at the right. The image’s overtly devout tone clearly indicates a religious destination, while the inclusion of lay devotees around the saint strongly suggests it belonged to a lay organization, like one based at the church of San Francesco in Lucca.[51]

Infrared reflectography detail of St. Sebastian’s chest, Madonna and Child with Saints John the Baptist, Sebastian, Margaret, and Mary Magdalen, acc. no. 37.431. Image by Pam Betts

The saints in the Walters tondo should provide clues to the identity of the person or organization who commissioned it. The Baptist and the Magdalen were two of the most popular confraternal saints because of their penitential associations: both spent parts of their lives in the wilderness, renouncing earthly pleasures and sustaining themselves on their faith. Here in the immediate foreground, they seem intent on keeping the viewer’s focus on the Virgin and Child, the Baptist by means of his gesture and the Magdalen with her fervent gaze. Saint Sebastian, protector against plague, was also of particular importance to confraternities, which were frequently involved with caring for those stricken by the disease.[52] That Sebastian was originally shown with five arrows lodged in his body, four of which were later painted out but visible with Infrared reflectography (fig. 24), would have further enhanced the image’s austerity, reminding the viewer of how he suffered for Christ. The presence of Saint Margaret is more difficult to explain, but opens the possibility of a women’s organization, since Margaret was often invoked for protection in childbirth.[53] Furthermore, the division of saints by sex can perhaps be understood as mirroring the constellation of devotees that might have gathered around the picture, ostensibly in the empty space before the two protagonists—another evocation of the “tondo as mirror” analogy. It is lastly worth underlining the overall tone of the tondo, at once pious and austere: in drawing on popular altarpiece conventions, it conveys a sense of pietism and reverence rarely encountered in tondi, which tend to tone down hieraticism in favor of an intimate mood appropriate to a domestic interior.[54] Considered together, these traits suggest the present panel was designed for a religious space, and, among the possibilities, a confraternal setting seems quite likely.

Master of the Johnson Magdalen (Italian, active ca. 1485–1515), Madonna and Child with Four Angels, Saints John the Baptist and Zenobius, ca. 1492, oil on panel, diam. 46 in. (117.1 cm). Buckingham Palace, Royal Collection, London, acc. no. RCIN 405685

With all this said, a domestic setting still cannot be ruled out, not least because the home was yet another space in which Florentines exercised devotion. In fact, at least one document attests to a sacra conversazione tondo being displayed in home. In 1492 the wealthy silk-weaver Zanobi di Giovangualberto Giocondo paid a certain painter named Cilio for a tondo which he displayed in his bedroom, “on which was painted Our Lady, Saint John, Saint Zanobi and many angels.”[55] Hitherto unidentified, this tondo is likely one in the Royal Collection (fig. 25): it depicts the same iconography, is stylistically consistent with a date of about 1492, and is by an artist known only by a conventional name, the Master of the Johnson Magdalen.[56] If indeed from Giocondo’s home, the picture would not only indicate that sacre conversazioni were suitable subjects for domestic tondi, it would also throw into further relief the unique austerity of the Walters example: as opposed to the latter’s bold hieraticism, Giocondo’s tondo, intended for his sumptuously decorated nuptial chamber, features the Virgin casually dressed, her hair loosely fixed and spilling over her shoulders. She is moreover patriotically accompanied by Florence’s two patron saints, who do not engage with the viewer, and all are placed in an elegant garden setting whose rich tapestry of colors lend an aristocratic dignity to the overall picture. These differences ultimately demonstrate the fluidity of the format in both domestic and public spaces, highlighting the artificially rigidity of our modern tendencies of categorization.

Whatever its origins, the Walters tondo remains a singular work, a noteworthy picture that embraces the conventions of a square-shaped altarpiece while simultaneously exploiting the inventive capacities of the circular format. It highlights the multivalences of the genre, throwing light on the numerous functions tondi once had and the many different spaces they occupied.

APPENDIX I: List of works by the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany

(* = attributions proposed here for the first time)

Note: Museum and collection accession or inventory numbers are given where available. When the listed location is not current, and the current location is not known, additional information appears in parentheses. Sale dates and lot numbers, when available, are given for artworks that were last known at auction. Many of these works can be found by searching the Fondazione Federico Zeri at http://catalogo.fondazionezeri.unibo.it/cerca/opera.

- Baltimore, MD

- Walters Art Museum

- 37.431. Tondo: Madonna and Child with Saints John the Baptist, Sebastian, Margaret, and Mary Magdalen.

- Walters Art Museum

- Berlin

- Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie

- 65. Nativity with Saints Dominic, Infant John, and Bernard.*

- Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie

- Cracow

- Wawel Castle

- 2177. Man of Sorrows with the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist.

- Wawel Castle

- Fiesole

- Museo Bandini

- Madonna and Child with Saints Francis, Julian, Lawrence, Bartholomew, Sebastian, and Catherine (much repainted), dated 1480.*

- San Francesco

- Adoration of the Magi with Saints Francis, Paul, and John the Baptist, after 1487.

- Museo Bandini

- Florence

- Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana

- Edili 148. Two illuminated initials: Translation of the Body of Saint Zenobius (fol. 58v), Persecution of Saint Reparata (fol. 85v), 1474.

- Galleria dell’Accademia

- 1890 n. 490. Coronation of the Virgin.

- 1890 n. 8623. Man of Sorrows with the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist.

- Oratorio dei Buonomini di San Martino

- Fresco lunette: Dream of Saint Martin, 1478–1479.

- Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana

- London

- Christie’s

- 10 April 1970, lot 13. Predella panel (to Los Angeles): Saint Vincent Ferrer Resurrecting a Child on an Altar.*

- Wallace Collection

- 768. Roundel: Madonna and Child.*

- Christie’s

- Los Angeles, CA

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- M.91.242. Volto Santo with Saints Vincent Ferrer, John the Baptist, Antoninus, and Mark (for the predella see London and Vienna).

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- New Haven, CT

- Yale University Art Gallery

- 1871.44. Penitent Saint Jerome and the Stigmatization of Saint Francis.*

- Yale University Art Gallery

- New York

- Wildenstein

- (in 1949; photo: I Tatti, no. 100616). Saint Humilitas.*

- Wildenstein

- Paris

- Galerie G. Sarti

- Pietà with Saint John the Evangelist.

- Galerie G. Sarti

- Saint Petersburg

- State Hermitage Museum

- ГЭ-9497. Pietà.

- State Hermitage Museum

- Seattle, WA

- Seattle Art Museum

- 39.59. Penitent Saint Jerome.*

- Seattle Art Museum

- Turin

- Galleria Sabauda

- 613. Madonna and Child with Saints Francis, Mary Magdalen, Catherine, and Jerome.*

- Galleria Sabauda

- Vatican City

- Vatican Library

- Urb.lat.1. Josiah in Galgala (fol. 87v),* Victory of the Jews over the Canaanites (fol. 97v),* David Witnessing the Murder of Amalekite (fol. 125r),* David and Bathsheba (fol. 138r),* Genealogy of Adam and Eve (fol. 167r),* Construction of the Temple of Jerusalem (fol. 196v), Nehemiah at the Court of Artaxerxes (fol. 201), Esther before Ahasuerus (fol. 224r),* 1477.

- Urb.lat.2. King David in Prayer (fol. 5r),* Supplication of Isaiah (fol. 68r), Arrest of Susanna and Execution of the Elders (fol. 141v),* Conversion of Saint Paul (fol. 250r),* 1478.

- Vatican Library

- Vienna

- Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie

- GG 6705, 6706, 6707, 6708, 6709. Five predella panels (to Los Angeles): Beheading of Saint John the Baptist; Saint Antoninus Consecrating the Oratorio dei Buonomini; Martyrdom of Saint Mark; Arrival of the Volto Santo at Luni; and Miracle of the Volto Santo in 1334.

- Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie

APPENDIX II: List of works here proposed as by the Master of 1493

- Amiens

- Musée de Picardie

- 4032. Madonna and Child with Two Angels.

- Musée de Picardie

- Amsterdam

- Rijksmuseum

- A3428. Adoration of the Shepherds.

- Rijksmuseum

- Avignon

- Musée du Petit Palais

- 20159. Madonna and Child with Saints Bernardino, John the Baptist, Jerome, Anthony of Padua, Peter Martyr, Francis, Louis of Toulouse, and Verdiana.

- 20258. Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian with Saint Bartholomew and a Bishop Saint.

- M.I.580. Madonna and Child with an Angel and Saint Benedict.

- Musée du Petit Palais

- Baltimore, MD

- Walters Art Museum

- 37.735. Madonna and Child with an Angel with the Penitent Saint Jerome and Tobias and the Angel in the Background.

- Walters Art Museum

- Bergamo

- Accademia Carrara

- D 61 (on temporary loan from the Ospedale Maggiore). Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Accademia Carrara

- Berlin

- Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie

- 1357. Entombment with a Dominican Monk as a Donor.

- Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum

- 1378 (destroyed 1945). Adoration of the Magi with Saints John the Baptist, Jerome, Lucy, James, Dominic and Francis, with the Trinity and the Three Archangels above.

- 1379A (destroyed 1945). Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Eugene Schweitzer

- (formerly). Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie

- Bern

- Dobiaschofsky

- 10 November 2023, lot 321. Coronation of the Virgin with Seven Angels and Saints Stephen, Michael, Gabriel, and Lawrence.

- Dobiaschofsky

- California

- Private Collection

- (in 2014; previously, Sotheby’s, New York, 28 January 2010, lot 241). Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Private Collection

- Compton Wynyates

- Marquess of Northampton

- Coronation of the Virgin with Saints Gabriel, Stephen, Catherine, Mary Magdalen, Lawrence, and Michael.

- Marquess of Northampton

- Copenhagen

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- 1748. Saint Sebastian.

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Cracow

- Czartoryski Museum

- XII-213. Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John and Two Angels.

- Czartoryski Museum

- Florence

- Giancarlo Baroni

- (in 1972; photo: Fototeca Zeri, no. 41329). Madonna and Child Enthroned (fragment).

- Enrico Frascione

- (in 2002; photo: Fototeca Fahy, no. 407699). Holy Family.

- Galleria dell’Accademia

- 1890 n. 8656. Saint Andrew Adoring the Cross with a Carmelite Nun as a Donor.

- Museo dell’Accademia delle Arti del Disegno

- 1890 n. 4667. Lamentation with Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Benedict, and Jerome.

- Museo Bardini, Corsi Collection

- 24. Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints Dominic, Peter Martyr, and a Diminutive Saint Catherine of Siena.

- Museo del Cenacolo di Andrea del Sarto

- 1890 n. 3453. Madonna and Child with Saints Francis, Matthew, Louis of Toulouse, and Clare, dated 1493.

- Museo degli Innocenti

- Three panels surrounding a fresco by David Ghirlandaio: Christ Blessing, Saints Andrew and Dionysius.

- Pandolfini

- 1 July 2020, lot 8. Saint John the Baptist.

- Private Collection

- (in 1985; photo: Fototeca Zeri, no. 39580). Holy Family.

- Salocchi

- (in 1970; photo: Fototeca Federico Zeri, no. 39669). Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Salvadori Collection

- (formerly; photo: Kunsthistorisches Institut no. 48065). Crucifixion with Saints Nicholas, Sebastian, Roch, and Tobias and the Angel.

- San Giorgio alla Costa, cloister

- Fresco: Double Intercession (same design as the Verrocchiesque panel in Montreal), dated 1487.

- Santi Girolamo e Francesco alla Costa, refectory

- Fresco: Last Supper, dated 1488.

- San Jacopo di Ripoli, ex-convento (Caserma Morandi)

- Fresco: Crucifixion with the Virgin, Saints Dominic, Peter Martyr, Mary Magdalen, John the Evangelist, James, and a Donor.

- San Niccolò Oltrarno, sacristy

- Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Villa La Pietra, Acton Collection

- XXX.C.10. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- XXX.C.18. Madonna and Child Enthroned with the Infant Saint John.

- Villa La Quiete, Pinacoteca

- Adoration of the Magi with Saints James and Dominic; lunette: Trinity with Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael with Tobias.

- Giancarlo Baroni

- Frankfurt am Main

- Städel Museum

- 1181 and 1182. Two spalliera panels: Horatius Cocles Defending the Sublician Bridge and Story of Mucius Scaevola, ca. 1485.

- Städel Museum

- Greenville, SC

- Bob Jones University Museum and Art Gallery

- 52.29. Madonna and Child with Saint Paul and a Bishop Saint.

- Bob Jones University Museum and Art Gallery

- Huntington, WV

- Huntington Museum of Art

- 1964.4. Madonna Adoring the Child with Saints Anthony Abbot, Peter, Infant John, Mary Magdalen, and Catherine.

- Huntington Museum of Art

- Königsberg (ex-Kaliningrad)

- Gemäldegalerie

- (on loan from Berlin, Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, inv. 1351; missing since 1945). Madonna and Child with Saints Francis, John the Baptist, Louis of Toulouse, and Bernardino.

- Gemäldegalerie

- Lille

- Palais des Beaux-Arts

- 804. Marriage of Saint Catherine with Saints John the Baptist, Louis of Toulouse, and Peter; lunette: God the Father.

- Palais des Beaux-Arts

- London

- Christie’s

- 30 March 1979, lot 39. Madonna and Child with Two Angels, Saints John the Baptist, Francis, Mary Magdalen, and Jerome.

- 12 October 1979, lot 49. Madonna Adoring the Child with Saints Jerome, Mary Magdalen, Francis, and the Infant John.

- 3 December 2008, lot 110. Madonna and Child with an Angel and Saint Benedict.

- Courtauld Gallery

- P.1966.GP.252. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John and Saint Peter Martyr.

- Pittas Collection

- Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Sotheby’s

- 3 July 1997, lot 61. Holy Family with the Infant Saint John with the Three Magi, Three Archangels, and Annunciation to the Shepherds in the Distance.

- Christie’s

- Lucerne

- Fischer

- 16 June 1959, lot 1862. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John and Saint Mary Magdalen.

- Fischer

- Madrid

- Fernando Durán

- 10–11 April 2018, lot 484. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John and Saint Ignatius of Antioch.

- Fernando Durán

- Mantua

- Claudio Lotti

- (in 1978; previously, Sotheby’s, London, 12 April 1978, lot 59). Tondo: Madonna and Infant Saint John Adoring the Child with the Stigmatization of Saint Francis in the Distance.

- Claudio Lotti

- Marseilles

- De Demandolx Dedons Collection

- (in 1928). Penitent Saint Jerome and Tobias and the Angel.

- De Demandolx Dedons Collection

- Mexico City

- Museo Soumaya

- 52310. Nativity with Twelve Angels and a Donor.

- Museo Soumaya

- Milan

- Finarte

- 15–16 May 1962, lot 92. Adoration of the Shepherds with the Infant Saint John.

- 17 May 1979, lot 70. Tondo: Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John and an Angel.

- 11 June 1996, lot 55. Spalliera panel: Martyrdom of Saint Ignatius.

- 21 November 1996, lot 52. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- 29 April 1998, lot 210. Holy Family with the Infant Saint John.

- Salamon Fine Art

- (in 2018). Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John and Saint James.

- Sotheby’s

- 9 June 2009, lot 12. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Finarte

- Munich

- Hampel

- 7 December 2016, lot 1239. Tondo: Madonna Adoring the Child with Two Angels.

- M. Porkay

- (in 1954; photo: Fototeca Fahy, no. 407714). Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Xavier Scheidwimmer

- (in 1964; photo: Fototeca Zeri, no. 42628). Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Hampel

- Nantes

- Musée Dobrée

- 856.27.1. Crucifixion with the Virgin, Saints John the Evangelist, Jerome, Mary Magdalen, and Anthony Abbot.

- Musée Dobrée

- New York

- Christie’s

- 10 June 1983, lot 181. Madonna Adoring the Child with an Angel, with God the Father above.

- 31 May 1991, lot 42. Tondo: Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John and an Angel.

- 14 January 1993, lot 101. Pietà with Saints John the Baptist, Jerome, and Mary Magdalen.

- 14 January 1994, lot 7. Nativity with the Infant Saint John.

- 28 January 2009, lot 1. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Moretti Fine Art

- (in 2012). Wings of a portable tabernacle: Annunciation, Stigmatization of Saint Francis, Penitent Saint Jerome; predella: Man of Sorrows with Saints Bernardino, Francis, Elizabeth of Hungary, and Barbara.

- Silberman Galleries

- (in 1960). Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Sotheby’s, Parke-Bernet

- 18 May 1972, lot 65. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- 7 April 1989, lot 30. Madonna and Child with an Angel and Saint Francis.

- 21 January 2004, lot 59. Madonna Adoring the Child.

- 26 May 2005, lot 132. Two panels: Saints Mary Magdalen and Margaret.

- 3 June 2010, lot 108. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John and Saint Francis.

- 25 January 2011, lot 52. Two spalliera panels: Story of Joseph.

- 26 January 2011, lot 210. Madonna and Child with Saints Jerome and Francis.

- 25 May 2022, lot 4. Lamentation with Saints Francis, Anthony of Padua, a Bishop Saint, Catherine, and Sebastian.

- Christie’s

- Northfield, MN

- Carleton College, Perlman Teaching Museum

- 1997.291. Two panels from the interstices of a portable triptych (see Paris, Baron Michele Lazzaroni): Annunciation.

- Carleton College, Perlman Teaching Museum

- Paris

- Artcurial

- 7 November 2012, lot 1. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Young Saint John.

- Giancarlo Baroni

- (in 1961). Crucifixion with the Virgin, Saints Dominic, John the Baptist, Antoninus, Jerome, Mary Magdalen, John the Evangelist, Francis, Bonaventure, Anthony Abbot, and a Donor.

- Galerie G. Sarti

- (in 2000). Spalliera panel: Adoration of the Magi, Nativity in the Distance.

- Baron Michele Lazzaroni

- (formerly). Wings of a portable triptych (formerly framed with a Crucifixion by Allegretto Nuzi at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 59.4): Saints John the Baptist and Michael. (see also Northfield).

- Artcurial

- Parma

- Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Parma

- 55954. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Parma

- Perugia

- Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria

- 1055. Holy Family with the Infant Saint John.

- Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria

- Philadelphia, PA

- Philadelphia Museum of Art, Johnson Collection

- Cat. 58. Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints Benedict, Bernard, Mary Magdalen, and a Bishop Saint. (only the central figures; the saints by another hand).

- Philadelphia Museum of Art, Johnson Collection

- Phoenix, AZ

- Phoenix Art Museum

- 1958.116. Tondo (cut from a paliotto?): Meeting of the Infants Christ and Saint John.

- Phoenix Art Museum

- Pisa

- E. Marianelli

- (in 1997; photo: Fototeca Fahy, no. 407715). Madonna Adoring the Child.

- E. Marianelli

- Prague

- Arthouse Hejtmánek

- 8 June 2023, lot 2. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John (repainted).

- Arthouse Hejtmánek

- Ratingen

- Fritz Tomée Collection

- 108. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Fritz Tomée Collection

- Rome

- Christie’s

- 13 April 1989, lot 127. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Galleria Colonna

- 1661. Spalliera panel: Massacre of the Innocents.

- Order of Malta

- Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Gloria Profili Venturi

- (in 1990; photo: Fototeca Fahy, no. 407745). Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Christie’s

- Saint-Quentin

- Musée Antoine Lécuyer

- MNR.851. Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John.

- Musée Antoine Lécuyer

- Vienna

- Dorotheum

- 17 October 2012, lot 501. Madonna and Child with an Angel.

- Dorotheum

- Zagreb

- Strossmayerova Galerija

- 48. Madonna and Child with Saints Cosmas and Damian.

- Strossmayerova Galerija

- Zurich

- Koller

- 19 September 2014, lot 3002. Penitent Saint Jerome, with the Martyrdom of Saint Peter Martyr and Miraculous Rescue of St. Placidus in the Background.

- Koller

- Whereabouts unknown

- Holy Family with the Infant Saint John and Saint Francis (photo: Fototeca Zeri, no. 42523).

- Madonna Adoring the Child with an Angel (photo: I Tatti, no. 100966).

- Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John (photo: Fototeca Zeri, no. 39413).

- Madonna Adoring the Child with the Infant Saint John (photo: Fototeca Zeri, no. 42516).

- Madonna Adoring the Child with Saints Jerome, Mary Magdalen, Infant John, and Francis (photo: National Gallery of Art, Offner archive, no. 1400454292 with “Rosselli school”).

- Madonna Adoring the Child with Two Angels (photo: Fototeca Zeri, no. 36978).

- Madonna and Child with Saints John the Baptist, Benedict, John the Evangelist, and Bernard (see Walter Angelelli and Andrea G. De Marchi, Pittura dal Duecento al primo Cinquecento nelle fotografie di Girolamo Bombelli, Milan: Electa, 1991, cat. 401).

- Madonna and Child with Two Angels (photo: Fototeca Zeri, no. 42524).

- Madonna and Child with Two Angels (photo: Fototeca Longhi, no. 0210024).

- Nativity with a Shepherd (photo: Fototeca Zeri, no. 42526).

Acknowledgments

Joaneath Spicer has kindly hosted me in the Walters Art Museum’s storerooms many times since my first visit in October 2014, when I asked to study the tondo discussed here. In 2018–2019 I was lucky enough to work with Joaneath as the museum’s Robert and Nancy Hall Curatorial Fellow. This article is intended as a modest thank you to Joaneath, not only for the generosity she has shown me over the years, but also for her enduring interest in my work. May it also reflect our shared enthusiasm for the many interesting Renaissance objects waiting to be rediscovered in storage. For helpful discussions about this tondo and its painter, I thank Davide Civettini, Nicoletta Pons, Rachel A. Young, and Floris de Beij.

[1] William R. Johnston, William and Henry Walters, the Reticent Collectors (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 153–69. For the objects purchased as part of the Massarenti collection, see Catalogue du musée de peinture, sculpture et archéologie au Palais Accoramboni (Rome: Imprimerie du Vatican, 1897), esp., 1:27, no. 140 (this painting).

[2] As this article was being prepared the picture was examined in the Conservation Studio by Pamela Betts and Karen French, senior conservators of paintings, and found to be in generally good condition. Contrary to the report in Federico Zeri’s catalogue entry (see note 3 below), the panel has not been cut. The border of the original gesso preparatory layer is visible around the edges. The panel also, for the most part, retains its original thickness, though at some point in the past the reverse was chamfered along the perimeter (this was probably done to fit it into a new frame). The surface is masked by a heavy varnish and dirt, and there is some repaint, most noticeably in Sebastian’s body, where no less than five arrows have been painted out.

[3] Federico Zeri, Italian Paintings in the Walters Art Gallery (Baltimore: Walters Art Gallery, 1976), 1:112, no. 74 (with previous bibliography), pl. 57.

[4] Fahy’s opinion, dated April 9, 1984, is recorded on photo-mount 707–9F in the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany file.

[5] Memo dated August 21, 1996, in the curatorial file. See also Luca Mattedi, “‘Tempi felici’: In ricordo di Lisa Venturini (1960–2005),” Il capitale culturale: Supplementi 13 (2022): 449–67, at 457.

[6] Nicoletta Pons and Matteo Gianeselli both endorsed the attribution in conversation with me. I also supported the attribution in a visit to the museum in 2014, as reported in a memo in the file dated October 30, 2014.

[7] See the list in Everett Fahy, “The Este Predella Panels and Other Works by the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany,” Nuovi Studi 6–7, no. 9 (2003): 17–29, at 22–25.

[8] Everett Fahy, “Early Italian Pictures in the Gambier-Parry Collection,” Burlington Magazine 109, no. 768 (1967): 128–39, at 133–34; Fahy, Some Followers of Domenico Ghirlandajo (New York: Garland, 1976), 169–70; and Fahy, “The Este Predella Panels,” 22–25.

[9] Anna Padoa Rizzo, “L’altare della Compagnia dei Tessitori in S. Marco a Firenze: dalla cerchia di Cosimo Rosselli a Cigoli,” Antichità Viva, no. 28 (1989): 19. The picture is usually dated a bit later, to about 1490, because of its compositional similarity to an altarpiece by Cosimo Rosselli, for which see Susan J. May and George T. Noszlopy, “Cosimo Rosselli’s Birmingham Altarpiece, the Vallombrosan Abbey of S. Trinita in Florence and its Gianfigliazzi Chapel,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 78 (2015): 97–133.

[10] Odoardo H. Giglioli, Catalogo delle cose d’arte e di antichità d’Italia 6: Fiesole (Rome: Libreria dello Stato, 1933), 171.

[11] Fahy, “Early Italian Pictures,” 133.

[12] Works documented to Filippo alone include the polychromy of a cross (1473), a painted baldachin and three banners (1494), and a Madonna at Palazzo Vecchio (1501). For the few known references to him, see Gaetano Milanesi, Nuovi documenti per la storia dell’arte toscana dal XII al XV secolo (Florence: Dotti, 1901), 160–61; Odoaro H. Giglioli, “L’antica Cappella Nenti nella Chiesa di Santa Lucia dei Magnoli a Firenze e le sue pitture,” Rivista d’arte 4 (1906): 184–88; Karl Frey, “Studien zu Michelagniolo Buonarroti und zur Kunst seiner Zeit, III,” Jarburch des Preuszischen Kunstsammlungen 30 (1909): 103–80, esp. 125; Sir Dominic E. Colnaghi, Dictionary of Florentine Painters from the 13th to the 17th Centuries (London: John Lane, 1928), 100; Eve Borsook, “Décor in Florence for the Entry of Charles VIII of France,” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 10, no. 2 (1961): 106–22, at 107 and 118; Padoa Rizzo, “L’altare della Compagnia dei Tessitori,” 17–24; Nicoletta Pons, “Zanobi di Giovanni e le compagnie di pittori,” Rivista d’arte, 7th ser., 4, no. 43 (1991): 221–27; Melinda Hegarty, “Laurentian Patronage in the Palazzo Vecchio: The Frescoes of the Sala dei Gigli,” Art Bulletin 78, no. 2, (1996): 264–85, at 277; Dennis V. Geronimus and Louis A. Waldman, “Children of Mercury: New Light on the Members of the Florentine Company of St. Luke (c. 1475–c. 1525),” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 47, no. 1 (2003): 118–54, at 123 and 145n36; and Nicoletta Pons, “Ricerche documentarie su Jacopo del Sellaio,” in Nicoletta Baldini, ed., Invisibile agli occhi: Atti della giornata di studio in ricordo di Lisa Venturini (Florence: Fondazione Roberto Longhi, 2007), 29–36, at 33.

[13] Padoa Rizzo, “L’altare della Compagnia dei Tessitori,” 17–24.

[14] Nicoletta Pons, “Dipinti a più mani,” in Mina Gregori, Antonio Paolucci, and Cristina Acidini Luchinat, eds., Maestri e botteghe: Pittura a Firenze alla fine del Quattrocento (Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editore, 1992), 35–44, at 35.

[15] Jean K. Cadogan, Domenico Ghirlandaio: Artist and Artisan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 208–13.

[16] Fahy, “The Este Predella Panels.”

[17] The two Florentine miniatures (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Edili 148, fols. 58v and 85v) were inadvertently recognized as the artist’s by Annarosa Garzelli when she linked them to the Buonomini Dream of Saint Martin; see Garzelli, Miniatura fiorentina del Rinascimento 1440–1525: Un primo censimento (Florence: Giunta, 1985), 1:150–63.

[18] As with the Florentine codex, Garzelli inadvertently recognized the Fiesole Master when she assigned at least one miniature in the Bible (Vatican Library, Urb.lat.2, fol. 68r) to the same artist as the Buonomini fresco (whom she called the “Maestro del sogno di San Martino”); see Garzelli, La Bibbia di Federico da Montefeltro: Un’officina libraria fiorentina 1476–78 (Rome: Multigrafica Editrice, 1977), 150. I believe the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany can also be recognized in the miniatures she associated with the Buonomini frescoes under various names (“Maestro del Oratorio dei Buonomini,” “allievo del Maestro del Oratorio dei Buonomini,” etc.). That the Fiesole Master worked in the Bible has been mentioned only in passing and without any specification as to which miniatures are his; see Everett Fahy in Andrea di Lorenzo, ed., Due collezionisti alla scoperta dell’Italia: Dipinti e sculture dal Museo Jacquemart-André di Parigi (Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana, 2002), 97; and Francesco Pasut, “Domenico, David e Benedetto di Tommaso di Corrado Bigordi detti del Ghirlandaio,” in Milvia Bollati, ed., Dizionario biografico dei miniatori italiani: Secoli IX–XVI (Milan: Bonnard, 2004), 199–200.

[19] Francesco was godfather of Benedetto Ghirlandaio, whom a tax declaration of 1480 describes as a miniaturist but whose work in this field has not been conclusively identified. Another artist who worked on the Bible, Attavante degli Attavanti, was godfather of Domenico Ghirlandaio’s son Antonio in 1489. See Nicoletta Baldini, “‘Tempi felici.’ La storia della famiglia del Ghirlandaio nelle carte conservate presso il fondo dell’Arciconfraternita del Gonfalone dell’Archivio Segreto Vaticano,” in Lisa Venturini, ed., with Nicoletta Baldini, Ghirlandaria: Un manoscritto di ricordi della famiglia Ghirlandaio (Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 2017), 1–183, at 65–66 and 96–97.

[20] For the state of the question, see Pasut, “Domenico, David e Benedetto,” 199–200. For their presence in the Florentine codex, see Mirella Levi D’Ancona, “Una miniatura qui attribuita a Benedetto Ghirlandaio,” Rara volumina 11, nos. 1–2 (2004): 13–23. For Domenico’s role in the Montefeltro Bible, see Giovanni Morello, “Pittori e miniatori per al Bibbia urbinate,” in Ambrogio M. Piazzoni, ed., La Bibbia di Federico da Montefeltro: Commentario (Modena: Panini Editore, 2005), 1:93–118, at 101–14; Ada Labriola, “Le miniature fiorentine della biblioteca di Federico di Montefeltro,” in Silvia Blasio, ed., Marche e Toscana: Terre di grandi maestri tra Quattro e Seicento (Florence: Banca Toscana, 2007), 47–48; and Labriola, “I miniatori fiorentini,” in Marcella Peruzzi, ed., Ornatissimo Vodice: La biblioteca di Federico di Montefeltro (Milan: Skira, 2008), 53–67, at 62.

[21] It might also be important that Cosimo Rosselli’s brother Francesco is thought to have played a role in Federico da Montefeltro’s Bible, and that Vasari assigned the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany’s Volto Santo to Cosimo himself. The Rosselli circle may provide another promising avenue of exploration.

[22] It is true that Filippo di Giuliano and Domenico Ghirlandaio are named together in several documents, but none suggest the type of working relationship seen here. In 1477 they were co-captains of the painters’ confraternity of Saint Luke alongside another painter, Piero del Massaio; see Geronimus and Waldman, “Children of Mercury,” 123. In 1483–1484 they were involved with different decorations of the Sala dei Gigli at Palazzo Vecchio—Ghirlandaio with figurative frescoes, Filippo di Giuliano and others with gilding the ceiling; see Hegarty, “Laurentian Patronage,” 277. On May 14, 1490, with Neri di Bicci they evaluated Francesco Botticini’s Tabernacle of the Sacrament at Sant’Andrea, Empoli; see Milanesi, Nuovi documenti, 160–61. The only document tying Filippo to a miniaturist is a notice of 1501 in which he and Zanobi di Giovanni leased a workshop from the illuminator Stefano Lunetti, their apparent partner; see Geronimus and Waldman, “Children of Mercury,” 145n34 and 151n69. Interestingly, documents of 1472 make note of Filippo’s activity in painting naibi (playing cards), an activity we might today consider in relation to manuscript illumination but which, in the period, was rather separate; see Pons, “Ricerche documentarie,” 33–34.

[23] Susan Caroselli, Italian Panel Paintings of the Early Renaissance (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1994), 71–72. She also describes the “brilliant color, decorative compositional arrangement, and horror vacui” as “hallmarks of a manuscript illuminator.”

[24] Fahy assigned these panels, held in Frankfurt at the Städel Museum, acc. nos. 1181 and 1182, to the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany; see Fahy, “The Este predella panels,” 23. For their links to the Lanfredini-Tommaso wedding, see Rudolf Hiller von Gaertringen, Italienische Gemälde im Städel 1300–1550: Toskana und Umbrien (Mainz: von Zabern, 2004), 371–91, there attributed to an anonymous Florentine and described—rightly, in my view—as stylistically incompatible with the Fiesole Epiphany.

[25] Padoa Rizzo, “L’altare della Compagnia de Tessitori,” 22; and Fahy, “The Este Predella Panels,” 23.

[26] Pons, “Zanobi di Giovanni.” Since the Master of 1493 most closely parallels Sellaio in his mode of production (i.e., a specialist in works for the domestic sphere), it may be that he, rather than the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany, is Filippo di Giuliano. Interestingly, as Padoa Rizzo observed, Filippo’s paternal house was in the parish of Santa Lucia dei Magnoli, and he later moved to the neighborhood of San Jacopo di Ripoli; see Padoa Rizzo, “L’altare della Compagnia dei Tessitori,” 21–22. Churches in both neighborhoods were home to works that Padoa Rizzo and Fahy assigned to the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany but that are here assigned to the Master of 1493. This patronage pattern might offer circumstantial support in identifying the Master of 1493 with Filippo di Giuliano. See the Last Supper at Santi Girolamo e Francesco sulla Costa, a Double Intercession at San Giorgio sulla Costa, two panels of the Adoration of the Magi for San Jacopo di Ripoli (Villa La Quiete, Florence; formerly Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, Berlin, acc. no. 1378, destroyed in 1945), and a fresco of the Crucifixion and Saints in the cloister of the same convent that remains in situ.

[27] Emanuele Zappasodi in Claudio Strinati, ed., Frank Dabell, trans., The Madonna: Eternal Woman (Paris: Galerie G. Sarti, 2019), 86–89.

[28] This work is recorded in a photograph at the Villa I Tatti, Florence (inv. 100616). A handwritten note by Nicky Mariano on the back of the photo assigns it to Bartolomeo di Giovanni. It was last recorded with Wildenstein’s, New York, in 1949, and before that was in the Chalandon collection, Parcieux.

[29] Roberta J. M. Olson, The Florentine Tondo (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 166–67.

[30] Olson, The Florentine Tondo, 60–61 and 80–106; Lisa Venturini, “Pro uno tondo Virginis Mariae: Riflessioni su forma, destinazione, iconografia nei tondi fiorentini. Il caso di Botticelli,” in Davide Gasparotto and Antonella Gigli, eds., Il tondo di Botticelli a Piacenza (Milan: Federico Motta Editore, 2005), 33–43; and Jonathan Katz Nelson, “Putting Botticelli and Filippino in Their Place: The Intended Height of Spalliera Paintings and Tondi,” in Nicoletta Baldini, ed., Invisibile agli occhi: Atti della giornata di studio in ricordo di Lisa Venturini (Florence: Fondazione di studi di storia dell’arte Roberto Longhi, 2007), 52–63, esp. 59–60. The format’s rich interpretive possibilities are explored in Roberta J. M. Olson, “The Rosary and Its Iconography. Part I: Background for Devotional Tondi,” Arte Cristiana 86, no. 787 (1998): 263–76; Olson, “The Rosary and Its Iconography. Part II: Devotional Tondi,” Arte Cristiana 86, no. 788 (1998): 334–42; and Edward J. Olszewski, “A Possible Source for the Triptych, Lunette, and Tondo Formats in Renaissance Paintings,” Source 28, no. 2 (2009): 5–11.

[31] Roberta J. M. Olson, “An Old Mystery Solved: The 1487 Payment Document to Botticelli for a Tondo,” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 39, no. 2–3 (1995): 393–96. Another example is Filippino Lippi’s documented Annunciation, two tondi painted in 1483–1484 for the Palazzo Comunale, San Gimignano, where they remain today as part of the town’s Museo Civico.

[32] Olson, The Florentine Tondo, 73 and 75. A notable painted example in a sacred space is the Madonna and Child by Bastiano Mainardi, frescoed in a trompe l’oeil stone tondo frame on the wall beside the altar in the chapel of the Bargello, Florence.

[33] “È di mano di Sandro in San Francesco fuori della porta a San Miniato, in un tondo, una Madonna con alcuni angeli grandi quanto il vivo: il quale fu tenuta cosa bellissima.” See Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori, ed. Gaetani Milanesi (Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1878–1886), 3:139.

[34] “In una cappella a man destra si vede, di mano di Sandro Botticelli, un tondo molto bello, nel quale è dipinta una Madonna col Figliuolo in collo et intorno sono angeli, che pare che con somma grazia cantino.” Francesco Bocchi, Le Bellezze della Città di Fiorenza dove a pieno di pittura, di scultura, di sacri templi, di palazzi I più notabili artifizi et più preziosi si contengono (Florence: n.p., 1591), 126.

[35] Herbert P. Horne, Botticelli, Painter of Florence (London: George Bell & Sons, 1908), 120.

[36] Venturini, “Pro uno tondo Virginis Mariae,” 39; Damian Dombrowski, Die religiösen Gemälde Sandro Botticellis: Malerei als pia philosophia (Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2010), 230; and Frank Zöllner, Sandro Botticelli (Munich: Prestel, 2005), 225 (with caution).

[37] Ronald Lightbown, Sandro Botticelli: Life and Work (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978), 2:54.

[38] Francesco Bocchi and Giovanni Cinelli mention another tondo in a Florentine church: a Visitation by Mariotto Albertinelli in San Pancrazio (lost); see La Bellezze della città di Firenze (Florence: Gugliantini, 1677), 206.

[39] Tondi less frequently show narrative episodes, most often the Adoration of the Magi or Annunciation. Compare late fifteenth- to early sixteenth-century examples in the Walters Art Museum, namely: Holy Family, acc. no. 37.436; Madonna and Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist, acc. no. 37.422; The Nativity, acc. no. 37.584; and Madonna and Child with the Young St. John and Two Angels, acc. no. 37.1040.

[40] Of course, sacre conversazioni appear in other object types. The Master of the Fiesole Epiphany, for example, painted one in a small panel, presumably for a domestic interior (Galleria Sabauda, Turin, acc. no. 613). For the terminology and history of the term, see David Ekserdjian, The Italian Renaissance Altarpiece: Between Icon and Narrative (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2021), 109–57, especially 110–16.

[41] See, for instance, the two tondi of the Madonna and Child with Saints Mary Magdalen and Catherine of Alexandria, one by the Master of Memphis (Museo Soumaya, Mexico City, acc. no. 53847), the other by Raffaellino del Garbo (National Gallery, London, acc. no. NG4903), both recorded at Palazzo Pucci, Florence, in the nineteenth century; if originally commissioned by the family, the tondi may indicate a special devotion to these two saints. See also the Lucchese painter Michelangelo Membrini’s Madonna and Child with Saints Jerome, Catherine and a Donor (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, acc. no. 68.PB.4), which includes the coats of arms of two families, presumably to commemorate a marital or mercantile alliance.

[42] Compare the small tondi by Botticelli (13 in. [34.4 cm]), Art Institute of Chicago, acc. no. 1954.282; Domenico Ghirlandaio (12 in. [31.5 cm]), Galleria di Palazzo Cini, Venice; Sellaio (16 in. [41 cm]), Musée Fesch, Ajaccio, acc. no. 852-1-838; Filippino Lippi (20 in. [53 cm]), State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, acc. no. ГЭ-287; and the Master of Marradi (17 in. [45 cm]), Petit Palais, Avignon, acc. no. 20157, among others.

[43] Tom Henry in Tom Henry and Laurence B. Kanter, Luca Signorelli: The Complete Paintings (London: Thames & Hudson, 2001), 150 and 228.

[44] Compare his painting at the Walters Art Museum, Virgin and Child Enthroned with Four Saints, acc. no. 37.700.

[45] Pons, “Ricerche documentarie,” 33–34.

[46] Ludovica Sebregondi, Tre confraternite fiorentine: Santa Maria della Pietà, detta ‘Buca’ di San Girolamo, San Filippo Benizi, San Francesco Poverino (Florence: Salimbeni, 1991), 123–96; and Barbara Wisch and Diane Cole Ahl, eds., Confraternities and the Visual Arts in Renaissance Italy: Ritual, Spectacle, Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000). For two spalliere sets by Botticelli likely from religious companies, see Bastian Eclercy in Andreas Schumacher, ed., Botticelli: Likeness, Myth, Devotion (Frankfurt: Städel Museum, 2009), 314–21, at 320; Annamaria Bernacchioni in Rachel McGarry and Cecilia Frosinini, eds., Botticelli and Renaissance Florence: Masterpieces of the Uffizi (Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2022), 104.

[47] For example, see the premises of the Compagnia della Purificazione as reconstructed by Ann Matchette, “The Compagnia della Purificazione e di San Zanobi in Florence: A Reconstruction of its Residence at San Marco, 1440–1506,” in Wisch and Ahl, Confraternities and the Visual Arts, 74–101.

[48] William R. Levin, “Confraternal Self-Imaging in Marian Art at the Museo del Bigallo in Florence,” Confraternitas 10 (1999): 3–14.

[49] On the formal relationship between tondi and mirrors, which in Quattrocento Florence were typically convex, see Olson, The Florentine Tondo, 95–101.

[50] This tondo measures 74 in. (189 cm) in comparison to the 68 in. (173 cm) of Filippino Lippi’s Corsini tondo (Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze), previously considered the largest surviving tondo (the largest known, as earlier mentioned, was Botticelli’s Madonna del Candelabra, destroyed in 1945). The Lucchese tondo has been mentioned in print only in Riccardo Massagli, “La bottega dei Ciampanti: Il Maestro di Stratonice e il Maestro di San Filippo,” Proporzioni 2–3 (2001–2002): 102n88, who thought it might be an old copy of a Quattrocento work because of the unusual absence of a gesso preparatory layer. This technical oddity may perhaps be explained by the work’s yet-to-be-determined original function and setting. For some further discussion, see Riccardo Massagli’s entry for the Catalogo dei beni culturali (inv. OA 09 00523911). I thank Giulia Coco for helping me examine the work firsthand.

[51] For women in Renaissance religious companies, at least in Florence, see John Henderson, Piety and Charity in Late Medieval Florence (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994), 110–12. For some information on the Compagnia Disciplinati dei Santi Francesco e Maria Maddalena at San Francesco, Lucca, see Gabriele Donati, “Arte e architettura in San Francesco di Lucca fino alle soglie del Cinquecento,” in Maria Teresa Filieri and Giuliano Ciampoltrini, eds., Il complesso conventuale di San Francesco in Lucca: Studi e materiali (Lucca: Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio, 2009), 98 and 102n232.

[52] Henderson, Piety and Charity, 121.

[53] For the women in Renaissance Florentine confraternities, see Henderson, Piety and Charity, 110–12.

[54] John Kent Lydecker, “The Domestic Setting of the Arts in Renaissance Florence,” (PhD diss., Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore 1987), 167–69; and Olson, The Florentine Tondo, 93.

[55] “…uno tondo d’albero; e fu dipinto Nostra Dona, Santo Giovanni, San Zanobi e più angioli.” Olson, The Florentine Tondo, 69n54.

[56] Maximillian Hernandez and Christopher Daly, “Un nome per il Maestro della Maddalena Johnson?,” forthcoming. Fahy assigned the tondo to the artist in a 2008 letter to the Royal Collection. See also, John Shearman, The Early Italian Pictures in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen (London: Phaidon, 1983), 208.