Unidentified German artist, Gingerbread Mold with Lovers, Southeast Germany or Austria, ca. 1475–1500, earthenware with lead glaze, 19 × 11.5 × 4.4 cm. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, museum purchase, 1973, acc. no. 48.2329

An unassuming piece of green-glazed earthenware lies among other vessels in the case of Northern Renaissance ceramics at the Walters Art Museum (fig. 1).[1] Decorated with a figural scene impressed into the ceramic, the oval concave pan is a matrix, probably made in Southeast German-speaking lands sometime at the end of the fifteenth or the beginning of the sixteenth century.[2] The current display of the mold modestly obscures its risqué scene. Upon closer inspection, one can observe the entangled body parts of a woman and a man, but a modern positive made by the Walters’ conservators in 1977 (fig. 2) unequivocally highlights the telling details.[3] The mold displays a young naked couple engaging in sexual foreplay. With her hands on her waist, the woman stands relaxed, anticipating her partner’s next move.[4] The man grabs her right breast, while trying to get closer to her loins with his erect penis. To reach the object of his desire, the man, being taller than the woman, must bend his knees, which conveniently allows him to fit into the frame of the mold. The couple’s outward gazes imply their awareness of the viewer, who interrupted their intimate moment.

Positive impression of the Gingerbread Mold with Lovers. The Walters Art Museum, acc. no. 48.2329

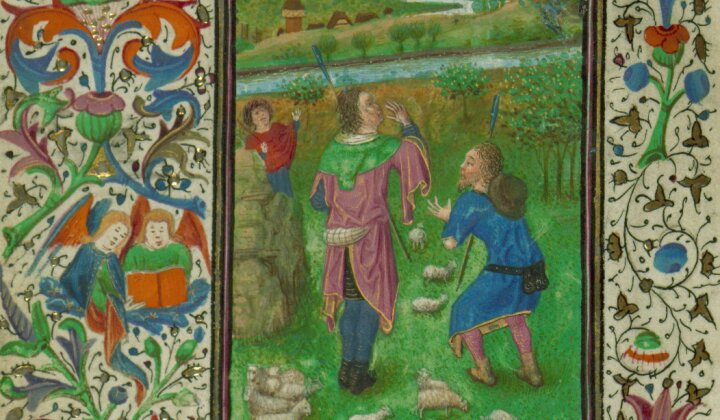

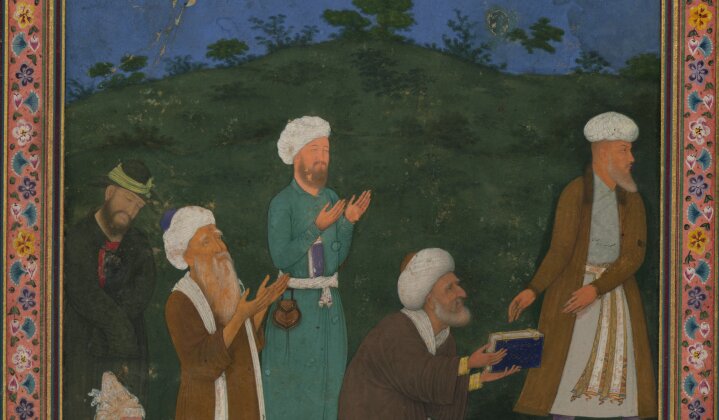

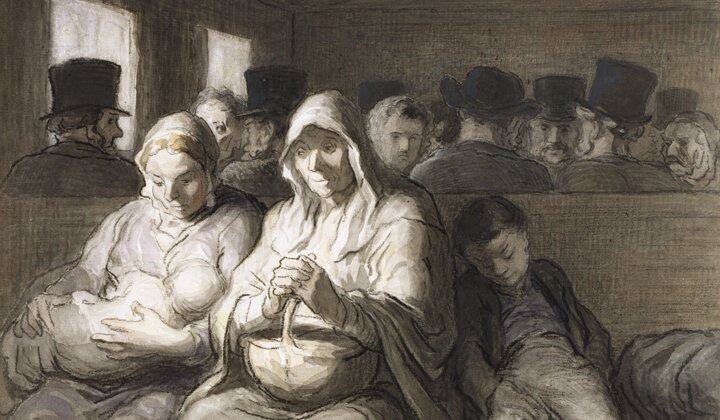

From the fifteenth century onwards, molds featured religious and profane scenes alike, but the theme of lovers was particularly prevalent. Besides molds depicting couples at leisurely activities in the fashion of medieval courtly romance, we also find many examples with more suggestive themes.[5] Several represent thinly veiled allegorical scenes (such as a couple surprised by death, or a couple at the fountain of youth), but the Walters mold belongs to a group of objects with more explicit imagery. An early sixteenth-century bawdy piece, now in Vienna, is a case in point (fig. 3). A man and woman sell some unusual merchandise out of a trunk, attracting the attention of two elegantly dressed ladies and a gentleman. A large phallus under the group of the figures makes the similarly shaped contents of the trunk unambiguous.[6] Meanwhile, some fifteenth- and sixteenth-century examples stand compositionally closer to the Walters mold, representing naked couples at sexual play (fig. 4).[7] These racy molds fit into a broader category of small-size erotica in various media (e.g., prints, plaques, stove tiles), suggesting a high demand for such objects in this period.[8] The Walters mold, too, was created to cater to the lascivious interest of a premodern audience, but the hot and spicy theme carried another connotation as well.

Unidentified Artist, Positive impression of Mold Who Buys Gods of Love?, early sixteenth century. Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, acc. no. F 578

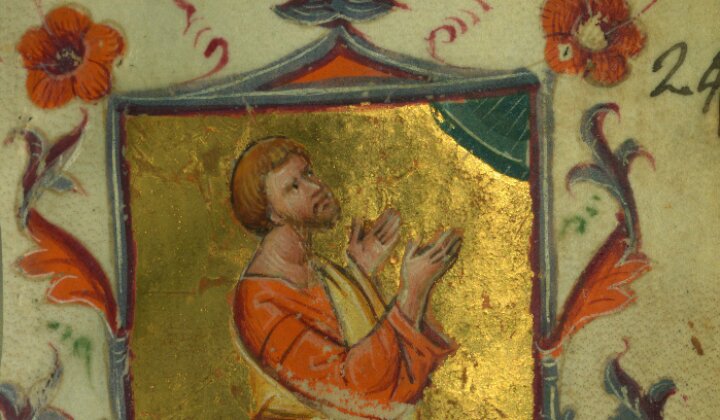

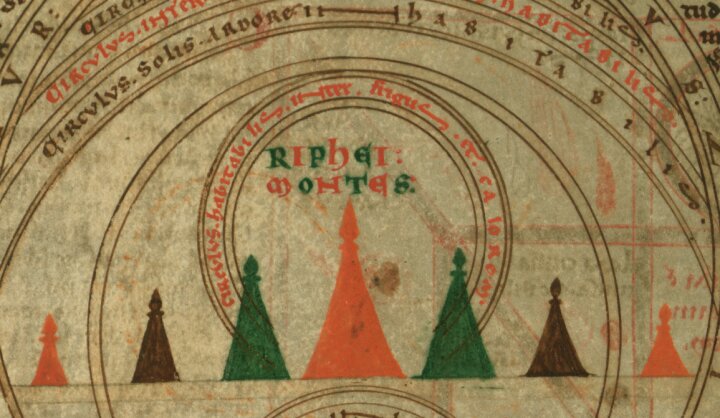

In addition to preparing images in wax, clay, papier mâché, and various kinds of metals (such as bronze or lead alloys), these molds were also used to bake gingerbread.[9] Due to the perishable nature of the spicy cookies, however, no actual examples have survived. Until further technical research is performed on the Walters mold, it remains an open question whether this particular vessel was used for baking gingerbread, but several comparative examples suggest so.[10] Using this mold to bake gingerbread not only allowed the baker to create many cookies with a salacious theme. The imagery itself added to the potency of the product. As a late fifteenth-century recipe from Bavaria shows, gingerbread (letzelten) was made of dough (tayg), clarified honey (lauterer honig), and a compound of spices, such as ginger (ingwer), clove (nagel), nutmeg (müscat), cinnamon (zimatrinten), and anise (anes).[11] In the twenty-first century, it may come as a surprise that medieval gingerbread recipes, such as this one, were preserved not in cookbooks but in medical miscellanies, revealing that it was not considered a dessert, but a potent remedy.[12] The above-mentioned recipe also underlines this quality of the cookie: “it is good and useful for many things and several illnesses” (Jst gar güet vnd nuotz zw vil dingen vnnd für manigerlay presten).[13]

Unidentified German artist, Positive impression of a Mold with Embracing Lovers (Liebespaar in Umarmung), fifteenth to sixteenth century, 10.6 × 6.8 cm. Published in 1918 as in the Stadtgeschichtliches Museum, Leipzig, acc. no. 04,195

Although this recipe does not specify what those things and illnesses are, we know that the valuable ingredients of gingerbread (honey and spices) were widely used for healing since antiquity.[14] Among the many therapeutic applications of these materials, they were also regarded as particularly beneficial for various aspects of sexual activities, as aphrodisiacs, enhancers of fertility, and drugs to treat various pregnancy conditions.[15] Thus the sweet and spicy material that once filled the mold enriched the layers of meanings of the final product. By impressing an image of an erotic theme on the dough filled with such potent ingredients, the baker turned the cookie into a medicine of sympathetic healing: conspicuously highlighting the sexual organs, the gingerbread image made the connection between the therapeutic ingredients and their intended targets manifest. The intricately molded piece of gingerbread, fragrant with spices and sweet from honey, would have been singularly suitable as a wedding gift, wishing to heighten the couple’s sexual aptitude, potency, and fertility.[16]

The Walters gingerbread mold is a fascinating work of art that lends insight into the interconnection of erotic, gastronomic, and therapeutic concerns of premodern people and testifies to their humorous take on these issues. It is a rare surviving example of late medieval everyday objects used for preparing food, as most comparable surviving earthenware with similar humorous-erotic themes were used for serving food or storing medicine.[17] Meanwhile, it also attests that explicit objects, so popular at the time, did not merely serve to titillate the viewers, but carried deeper, practical meaning for their consumers, bringing them delight and sweet remedies.

Acknowledgments

I thank Angie Elliott for discussing this mold, sharing her material with me, and her quick conservation work. Additionally, I appreciate Ariel Tabritha for digitizing the old photo of the impression of the Walters’ mold and taking new photographs for this publication. I am grateful to Maria-Luise Jesch (MAK, Vienna) for sharing provenance and bibliographical information about the molds in their collection. Finally, I thank the anonymous reviewers, Giulio Sorgini, and Kristina Potuckova, whose comments have significantly improved this paper.

[1] This object once likely belonged to the Viennese collector Oscar Bondy (1870–1944), whose collection was confiscated by the Nazis after the Anschluss. The object might have been listed as the “green-glazed mold of a bridal couple in clay” (Grünglasierter Brautpaarmodel aus Hafnerton) in the Nazi-generated inventory of the Bondy collection, see Sophie Lillie, Was einmal war: Handbuch der enteigneten Kunstsammlungen Wiens (Vienna: Czernin, 2003), 232. In 1946 or thereafter, the mold was likely restituted to Oscar Bondy’s widow, Elisabeth Bondy, New York. I could not, however, confirm this from the Bondy restitution papers, College Park, MD, National Archive, Ardelia Hall Records: Status of Collecting Point Munich: Transport Lists-Austria (RG 260, Roll 76, https://www.fold3.com/image/270063892, last accessed, June 25, 2023), Custody Receipts on Restitution to Austria (RG 260, Roll 19, https://www.fold3.com/image/270053303, last accessed, June 25, 2023), Munich Property Cards (RG 260, Roll 168–169, https://www.fold3.com/publication/906/ardelia-hall-collection-munich-property-cards, last accessed, June 25, 2023). The “Dish with reliefs of Adam and Eve” (Munich no. 2295/18) is a different object. After the restitution, Elisabeth Bondy immediately sold many objects to the gallery of Leopold Blumka, New York; the mold was probably transferred to Blumka around this time, from whom the Walters acquired it in January 1973.

[2] For a short description of molds, see Herbert Kürth, Kunst der Model: Kulturgeschichte der Back- und Hohlformen (Gütersloh: Prisma, 1981), 7–8. Several fifteenth- and sixteenth-century comparative examples of green-glazed molds in Austrian collections indicate the Southeast German or Austrian origin of the Walters mold. For example, see the Mold with Bath Scene (sixteenth century, Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, acc. no. ME 771), Paul Preuning’s Mold with a Dancing Peasant Couple (Nuremberg, ca. 1548, Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, acc. no. ME 770), Mold with the Judgement of Paris (Alsace, fifteenth century, Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, acc. no. F 590), Mold of Man’s Head (Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, acc. no. ME 801), Mold with the Coat of Arms of Archbishop Leonhard von Keutschach(beginning of the sixteenth century, Salzburg Museum, acc. no. 25-24), Mold with Easter Lamb (Salzburg Museum, acc. no. K 4970-49), Mold with Lobster (Salzburg Museum, acc. no. ARCH 6630-94). On these green-glazed molds at the Museum Angewandte Kunst in Vienna, see Alfred Walcher-Molthein, “Zur Geschichte der Formmodel für Feingebäck und Zuckerwerk,” Belvedere 5 (1924): 201–20, at 218. The earliest mention of a professional gingerbread baker in Vienna is from 1394, see Walcher-Molthein, “Zur Geschichte der Formmodel,” 215.

[3] For a detailed description of the preparation of the positive and the four color slides of it, see the conservation file of the object (Oct. 6, 1977), to which conservator Angie Elliott has kindly called my attention.

[4] As Joaneath Spicer has pointed out in her important study on Renaissance elbows as a manifestation of male dominance, this gesture was highly unusual in the representation of women, see Joaneath Ann Spicer, “Renaissance Elbow,” in Jan N. Bremmer and Herman Roodenburg, eds., A Cultural History of Gesture (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992), 84–128, at 100.

[5] Wilhelm von Bode and Wolfgang F. Volbach, “Mittelrheinische Ton- und Steinmodel aus der ersten Hälfte des XV. Jahrhunderts,” Jahrbuch der Königlich Preussischen Kunstsammlungen 39 (1918): 89–134, at 94; Walcher-Molthein, “Zur Geschichte der Formmodel,” 204; and Kürth, Kunst der Model, 14–17 and 99–103.

[6] Bode and Volbach have enigmatically called this scene “Wer kauft Liebesgötter?” (Who buys gods of love?) See Bode and Volbach “Mittelrheinische Ton- und Steinmodel,” 133, no. 71. On this antique theme and its modern artistic revival, see Dietrich Gerhardt, Wer kauft Liebesgötter?: Metastasen eines Motivs (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2008).

[7] E.g., the example illustrated in figure 4 that was published by Bode and Volbach as in the Stadtgeschichtliches Museum, Leipzig, acc. no. 04,195, although later publications indicate it may instead be in Kassel, and Volkskundemuseum, Odenwald in Heppenheim, number unknown; on these molds, see Bode and Volbach, “Mittelrheinische Ton- und Steinmodel,” 97 and 133, no. 68; and Kürth, Kunst der Model, 16. For the first mold, see also Fritz Arens, “Die ursprüngliche Verwendung gotischer Stein- und Tonmodel mit einem Verzeichnis der Model im mittelrheinischen Museen,” Mainzer Zeitschrift 66 (1971): 106–31, at 121.

[8] On the popularity of fifteenth-century erotic prints, see Keith P. F. Moxey, “Master E. S. and the Folly of Love,” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 11, no. 3–4 (1980): 125–48, at 125; on the sixteenth-century erotica, see James Grantham Turner, “Profane Love: The Challenge of Sexuality,” in Andrea Bayer, ed., Art and Love in Renaissance Italy (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008), 178–84.

[9] Kürth, Kunst der Model, 8. On medieval textual evidence for baking gingerbread in figural molds, see Kürth, Kunst der Model, 20. Previously, Bode and Volbach vehemently dismissed the idea that fifteenth-century molds were used for baking. On metal, clay, and papier maché images made with such molds, see Bode and Volbach, “Mittelrheinische Ton- und Steinmodel,” 101–104. They were used to decorate other objects as well; see Bode and Volbach, “Mittelrheinische Ton- und Steinmodel,” 102–109.

[10] The holes drilled (?) into the Walters mold might have functioned to release the steam evaporating during baking. For a similar observation on other molds, see Walcher-Molthein, “Zur Geschichte der Formmodel,” 218.

[11] Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, acc. no. Cgm 725, fol. 41r, Tegernsee, last quarter of the fifteenth century. For a transcription of the recipe, see Astrid Böhm and Helmut W. Klug, “Transcription of M5: ‘München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cgm 725,’” in Helmut W. Klug et al., eds., CoReMA, Cooking Recipes of the Middle Ages: Corpus, Analysis, Visualisation (2021), http://hdl.handle.net/11471/562.10.3819. On this recipe, see also Helmut W. Klug, “‘gewürcz wol vnd versalcz nicht:’ Auf der Suche nach skalaren Erklärungsmodellen zur Verwendung von Gewürzen in mittelalterlichen Kochrezepten,” Medium Aevum Quotidianum 61 (2010): 56–83. On the various qualities of honey and their trade in the late Middle Ages, see Alexandra Sapoznik, Lluís Sales I Favà, and Mark Whelan, “Trade, Taste and Ecology: Honey in Late Medieval Europe,” Journal of Medieval History 49, no. 2 (2023): 252–74, https://doi.org/10.1080/03044181.2023.2188603.

[12] Gingerbread gradually became a coveted dessert in this period. The first recipe in a cookbook that survives is dated to around 1533; see Klug, “gewürcz wol vnd versalcz nicht,” 72.

[13] Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, acc. no. Cgm 725, fol. 41r. The quick beneficial effects of gingerbread on health was also emphasized by a household inventory in Strasbourg from 1514; see Kürth, Kunst der Model, 20.

[14] Andrew Dalby, “Plants as Luxury Foods: ‘Sweet Herbs for Curry,’” in Annette Giesecke, ed., A Cultural History of Plants in Antiquity, vol. 1 (New York: Bloomsbury, 2022), 49–51; Iolanda Ventura, Tony Hunt, and Johannes Gottfried Meyer, “Plants and Medicine,” in Alain Touwaide, ed., A Cultural History of Plants in the Post-Classical Era, vol. 2 (New York: Bloomsbury, 2022), 109.

[15] For example, see the recipes in Monica H. Green, ed. and trans., The Trotula: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine, Middle Ages Series (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 68–70, 77, 89–90, and 109–110.

[16] It was a custom since antiquity to give food containing honey as wedding gifts; see Adelheid Sallinger, “Honig,” in Ernst Dassmann, ed., Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum (Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1994), 452. Gingerbread was also part of late medieval and early modern wedding feasts, and gingerbread molds were given as wedding gifts; see Kürth, Kunst der Model, 14, 22, 24, and 57.

[17] See, for example, the remarkable Dish with a Composite Head of Penises (1536), Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, acc. no. WA2003.136; and the Medicinal Jar with a Shepherdess Lifting Her Skirt (ca. 1510–1520), The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, acc. no. 48.2234.