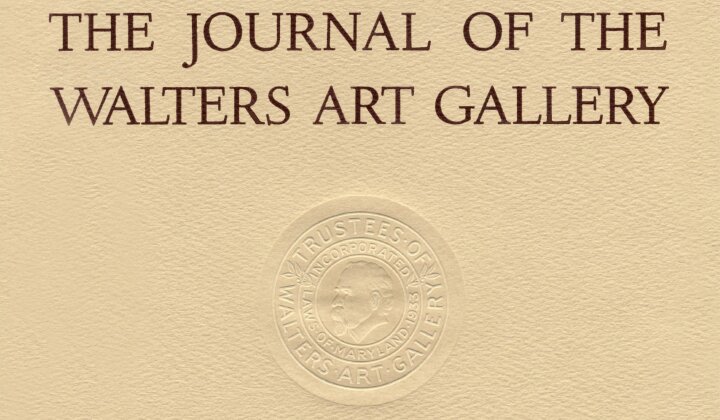

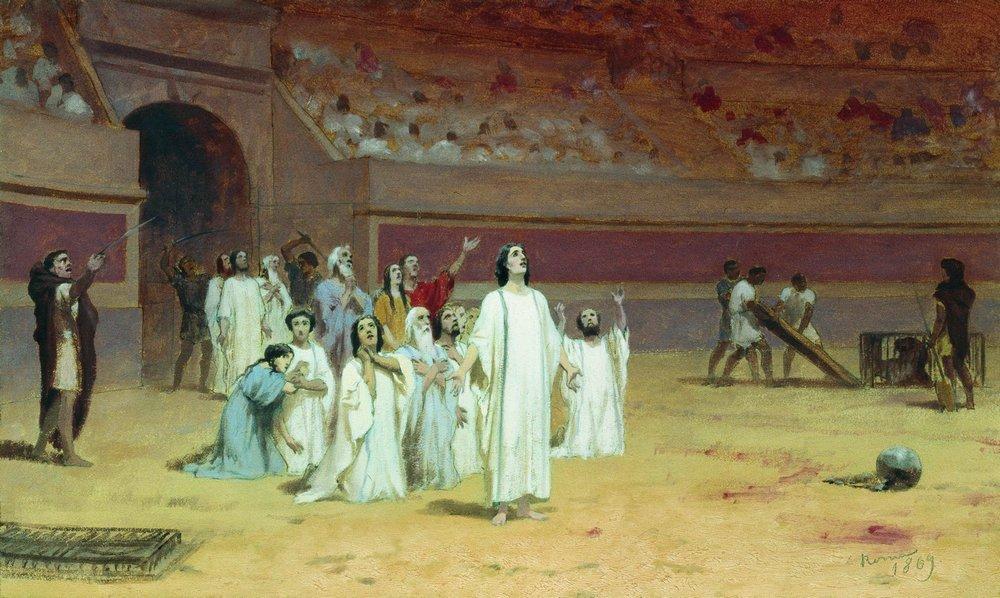

Jean-Léon Gérôme (French, 1824‒1904), The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer, 1883, oil on canvas, 34 5/8 × 59 1/8 in. (87.9 × 150.1 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, acquired by William T. Walters, 1883, acc. no. 37.113

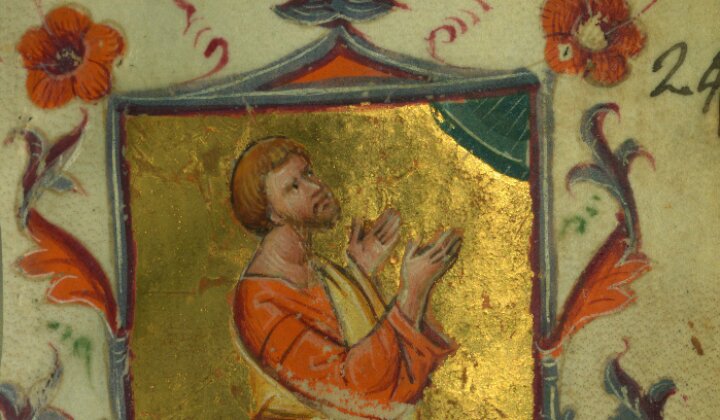

The striking painting in the Walters Art Museum The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer (1883) (fig. 1), by the French academic artist Jean-Léon Gérôme (Vesoul, 1824‒Paris, 1904), is part of the tradition of damnatio ad bestias (condemnation to beasts), a fertile theme that had interested artists of many nationalities and backgrounds, but which in the last decades of the nineteenth century experienced an unprecedented development and popularity, following in the wake of the then very fashionable “archaeological painting.”[1] Two main factors helped the success and the persistence of the theme of martyrdom. First was the great acceptance of some novels such as Les martyrs (1809) by François-René de Chateaubriand or, later, Quo Vadis (1896) by Henryk Sienkiewicz, works that contributed decisively to turn the torture of Christians into one of the main topics of nineteenth-century popular iconography. In this sense, the art critic Ivo Blom, proposing a very graphic simile, claims that the topic had captured the imagination of the middle class to such an extent that its popularity would be comparable to that of “the dinosaurs of Jurassic Park in our own time.”[2] Secondly, there is an ideological reason related to the general change in taste that the century witnessed as it left Romanticism behind. As Tomás Pérez Vejo states, whereas at the beginning of the century “the fascination for the primitive Church and the martyrs had attracted […] the attention of the first romantics” because “they saw in them the same purity of feelings they longed for,” as the century progressed, the fascination, still alive, was increasingly related to the fact that the triumph of Christianity over the cruel and barbaric Rome “acquired a deep moral meaning, since it not only meant the end of an era, but also the fair punishment for their depravity.”[3]

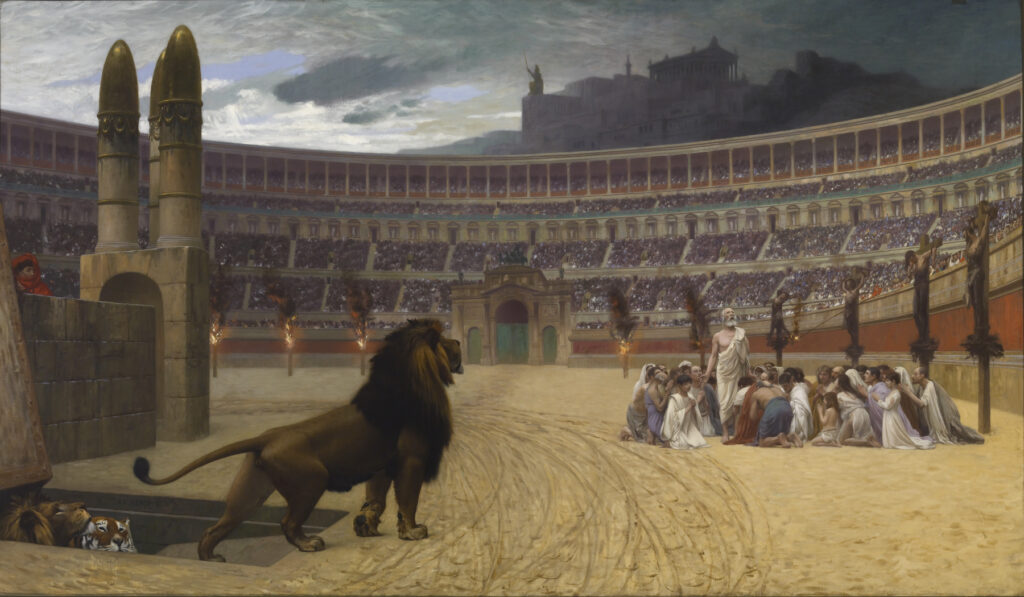

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Chariot Race, 1876, oil on cradled panel, 34 × 61 7/16 in. (86.3 × 156 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, George F. Harding Collection, acc. no. 1983.380

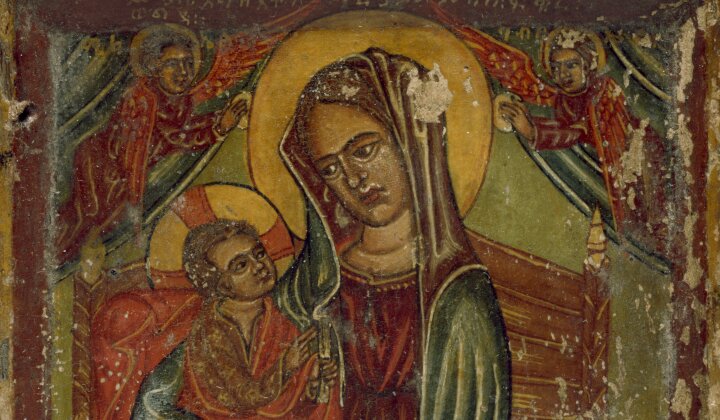

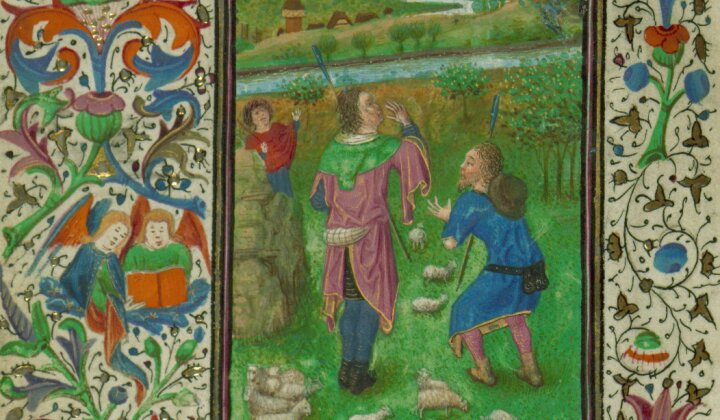

The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer is actually the centerpiece of three works by Gérôme that deal with this theme. Apart from depicting the same setting as a painting in the Art Institute of Chicago, Chariot Race (also known as Circus Maximus) (1876) (fig. 2), of which, in fact, The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer can be considered a prolongation, more than two decades later it would see a violent narrative continuation in The Retreating Lions (1902) (fig. 3), one of the last works signed by the artist. The painting now at the Walters Art Museum had been commissioned by the merchant, financier, and investor William Thompson Walters, directly from the artist in the early 1860s through George A. Lucas, yet it was not finished until 1883. During those more than twenty years in which he was pondering the work, Gérôme had doubts and difficulties that were unusual for him. These were perhaps due to the particular difficulty of the subject and probably also to the fact that, on this occasion, he could not go to the book he usually used to help him set the atmosphere for his Roman-themed paintings, the famous Rome au siècle d’Auguste (Rome at the time of Augustus) produced by Louis Charles Dezobry in 1835 with its four volumes packed with engravings and meticulously documented explanations of everyday life in antiquity.[4] As its title makes clear, this work is set in the early years of the first century CE, so the theme of Christian martyrs, logically, does not appear in it. This time, therefore, Gérôme had to elaborate the narrative construct of the scene almost from nothing.

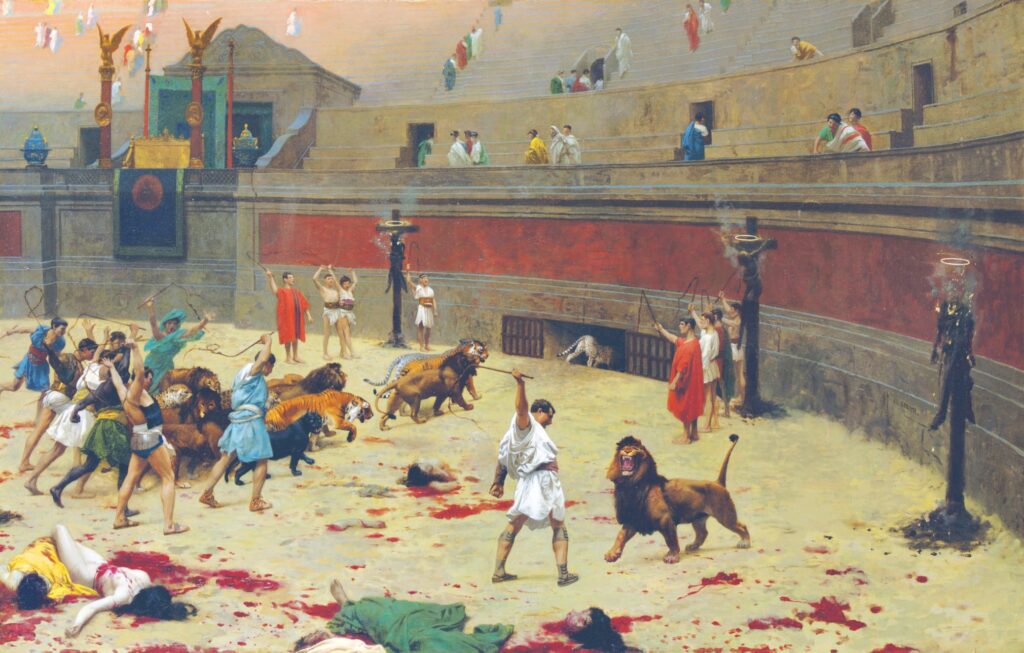

Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Retreating Lions, 1902, oil on canvas, 32¾ × 51 in. (83.2 × 129.5 cm). Khanenko Museum, Kyiv

The artist himself commented on all these troubles in the letter that he attached to the painting when he finally managed to finish it and send it to Baltimore:

My dear sir,

I am sending you some notes on the subject of my painting Christians to the beasts [sic] that you have acquired. I’m sorry to have kept you waiting so long, but I had a difficult task, and I was determined not to finish it until I had achieved the most of what I was capable of. This painting has been on my easel for over twenty years. I’ve completely repainted it three times;[5] I have removed and changed both the effect and the composition, while always keeping my first idea.

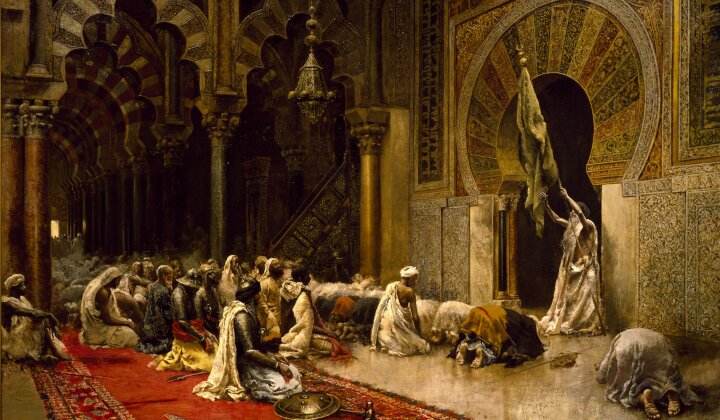

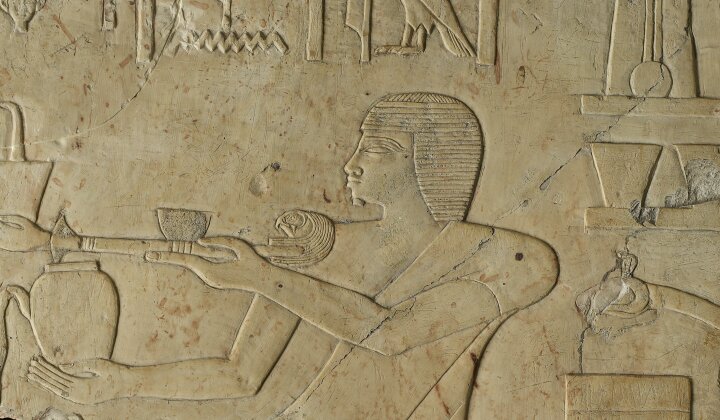

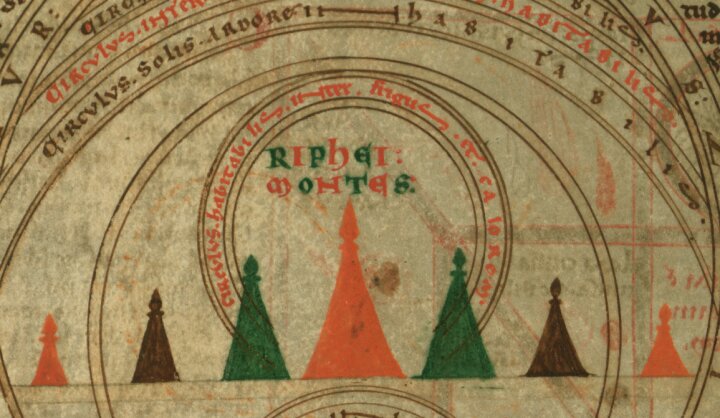

Therefore, the canvas you receive is actually the third one. The scene takes place in the Circus Maximus, which could easily be mistaken for an amphitheater, because the canvas shows only its end part and not the straight sides. But you will see that on the left is the goal where the spina ends, which the cars tried to avoid during the race, as indicated by the tracks left in the sand.

The Circus Maximus was one of the most robust monuments ever built. It could hold more than one hundred and fifty thousand spectators. To its left it bordered the Palace of the Caesars, from which an underground passage led directly to the emperor’s box.

In the time of the Caesars, Christians were cruelly persecuted and many were condemned to be eaten by wild beasts. This is the subject of my painting.

Their faith was fervent, dying was bliss. They were not very affected by animals; their only thought was to hold their own until the end. Apostasy was extremely rare. Roman prisons were terrible dungeons and Christians, often incarcerated long before the sacrifice, were decimated by disease and appeared covered in rags when led to the circus. Only their hearts remained strong, only their faith remained unshakeable. In the middle distance, I have placed those to be burned alive. In general, these were tied to crosses and smeared with tar to feed the fire. On this subject, Tacitus says: “Surely these Christians deserved to be executed; but why cover them with tar and burn them like torches?”[6] However, his sympathy did not go further.

It was customary to have wild beasts fasting during the previous days, and a ramp was put on them so that they could reach the arena. Coming from their dark lairs, his first reaction must have been surprise to find daylight and the great mass of people around him. Then they did what the Spanish bull does today when he is thrown into the arena: he leaves and suddenly stops in the middle of the ring. It is just this moment that I have tried to represent.

I consider this painting to be one of my most reflective works, for which I have suffered the most tribulations.

Please accept my warmest regards,

J.-L. Gérôme[7]

As we can see, the first point that Gérôme wants to clarify about his scene is the location where it takes place being the circus, not the amphitheater. His point is undoubtedly intended to combat the common belief that the damnationes only took place in the amphitheater and not in the circus,[8] when, in fact, they were not only carried out interchangeably in both types of buildings, but even in theaters, forums, or temporary wooden enclosures, as shown by the confusion and swapping of the terms circus, amphitheatrum, theatrum, stadium, arena, etc., already in the classical texts themselves.[9] In fact, as Monique Clavel-Léveque has shown, in the ancient mind all those buildings or venues dedicated to great shows were equally conceived as religiously and politically connoted spaces that helped regulate the Roman social universe and strengthen imperialism.[10] Despite his clarification, Gérôme contributes to the confusion by showing only the “end part and not the straight sides” of the building, so that the ellipse closely resembles the amphitheater of his first two arena paintings: Ave, Caesar, Morituri Te Salutant in 1859[11] and Pollice Verso in 1872.[12]

Detail of the Arch of Titus, The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer

On the other hand, the trapdoor through which the felines ascend to the circus is clearly an artistic license, since constructions of this type for circuses are not attested (the animals probably accessed from the sides).[13] In the same way, the elevated citadel in the background, while it looks like Athens, is probably meant to be the Palatine Hill, which did and does loom over the Circus Maximus to the east and was covered with imperial residences. As for the triumphal arch (fig. 4), it is the same one that is barely intuited at the bottom of The Chariot Race, so the completion of at least this part of the painting should probably be dated after 1876.

An Instant before Cruelty

Regarding the subject of the painting, Gérôme only comments succinctly that his intention was to show the cruelty to which Christians devoured by wild beasts were subjected. Instead, it is interesting to see how later he does expand on commenting on the moral attitude with which the martyrs accepted their fate: “Their faith was fervent, dying was bliss. They were not very affected by animals; their only thought was to hold their own until the end. […] Only their hearts remained strong, only their faith remained unshakeable.” These words show that, in reality, the artist’s ultimate intention was not to show the damnatio ad bestias itself, but rather to highlight the integrity with which Christians faced the test of faith that martyrdom inflicted. A tradition that, of course, is consolidated in the Western imagination by texts such as, to cite just one example, the following excerpt from Pope Clement’s First Letter to the Corinthians (5:2‒6, 6:1):

Out of jealousy and envy, the greatest and most righteous pillars [the first apostles] were persecuted and had to fight to death. Let us put before our eyes the example of the good apostles: Peter, who through unjust envy endured not one or two but many torments, thus reached, with martyrdom, the way to glory. […] And Paul, […] after being chained seven times and having been exiled and stoned, he became a preacher both in the East and in the West and obtained the noble fame of the faith. To these men, who lived so holy, we must add a great multitude of chosen ones who, after suffering numerous outrages and torture out of envy, are a beautiful example for all of us.

In fact, the custom of iconographically locating the martyrdoms of Christians in circuses or amphitheaters dates back to antiquity, being a consolidated tradition of which Gérôme and the multitude of nineteenth-century painters who addressed this subject are but the last link.[14] Furthermore, in Christian literature, Roman public leisure buildings not only have a high and positive symbolic value but also represent an inherent part of martyrdom because, as Jordina Sales-Carbonell recalls, the ideology of sacrifice founded on the Pauline paradox that “dying in Christ is living” specifically and proudly refers to the spectacle of martyrology as redemption and to martyrs as a kind of gladiators of faith.[15]

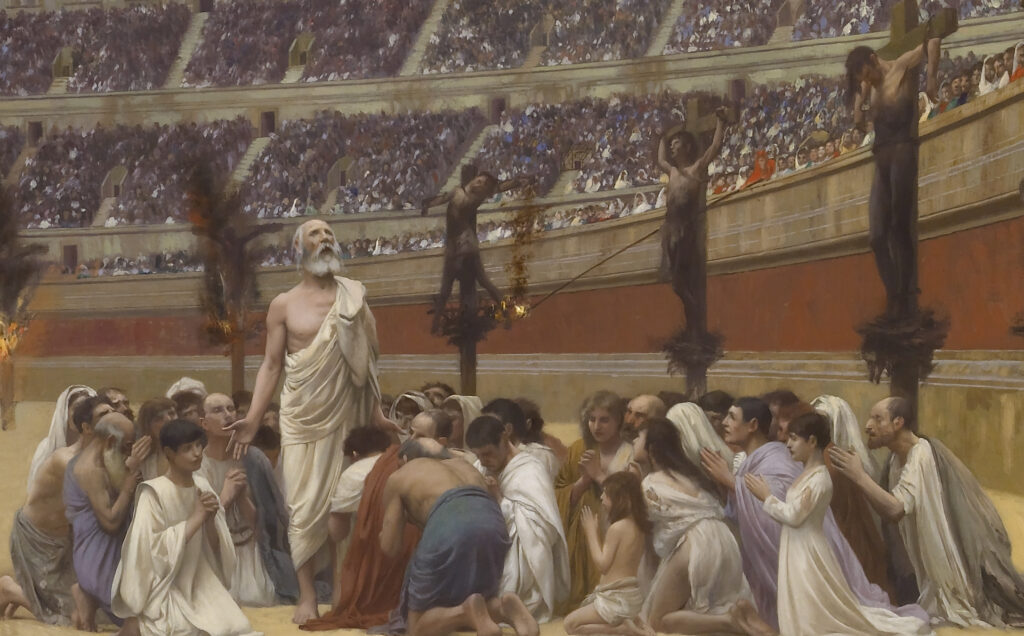

In Gérôme’s painting, the Christians waiting to be devoured by the felines are a tiny group of figures situated some distance away but make the viewer empathize with them due to their mostly white robes, which denote the innocence of their death, and their body language, which is not despair or fear at all but calm and serenity.[16] A similar strength is sensed in the poor unfortunates who are going “to be burned alive” on their crosses. On this subject, Gérôme paraphrases from memory the authority of a famous passage in which Tacitus, while acknowledging that Christians deserved to be executed, affirms that there was no need to burn them as human torches.[17] This is an assertion that is one of the few contemporary complaints to the refined tortures that Nero inflicted on Christians after blaming the fire of Rome in the summer of 64 CE on them.[18] The entire text reads:

Therefore, all those who pleaded guilty were arrested and later, with the information they gave, a large crowd was arrested, not so much for the crime of setting the city on fire as for their hatred against mankind. Besides killing them [the Christians] they were used as entertainment: some were dressed in the skins of beasts so that the dogs could devour them with their teeth. Others were crucified. And others were set on fire so that at the end of the day they would light up like torches. Nero provided his own gardens for this show and in the circus he himself offered a function where, dressed as a charioteer, he mingled with the mob or circled with his chariot. As a consequence of this, the mercy of the people was awakened, even against a people so guilty and deserving of exemplary punishment.[19]

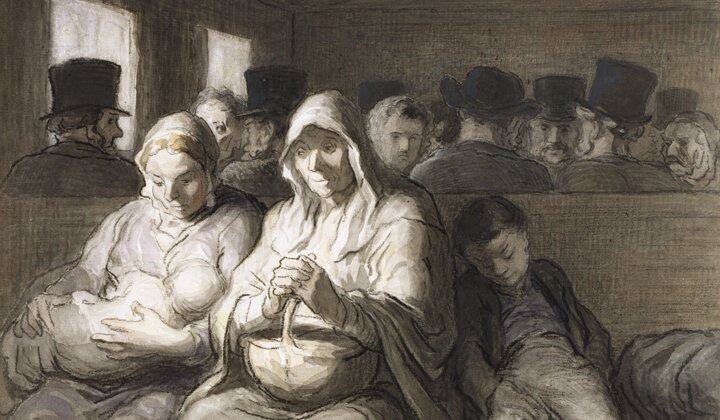

In the Walters painting, we are only given to understand that, after a long day of racing,[20] it is time to subject a group of Christians to the damnatio ad bestias, one more of the many macabre shows that were carried out in the buildings of Roman leisure. But, as usual, Gérôme does not organize the action around a particular central figure, as the traditional canons of history painting did, but he prefers to place the group of martyrs rather imprecisely on the periphery of the composition.[21] Even so, when the viewer becomes aware of their presence, they immediately understand that, as Marc Gotlieb affirms, these “constitute just one part of the picture’s narrative machinery, whose structure and operation they have only begun to explore.”[22] In fact, it can be said that in The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer the narrative treatment reaches the summit of the ingenious artist’s tricks devised to give temporary mobility to his paintings. In this case, the trick works on two levels: on the one hand, the faint light of the Roman sunset shows the observers what moment of the day it is and the aforementioned chariot tracks on the ground make them understand what has been happening in that place throughout the day. On the other hand, the presence of the beasts and the crosses clearly indicates what is about to happen, and that the Christians can do nothing to prevent it, which is why their calmness is increased.

Detail of the incensor setting fire to the crucified martyrs, The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer

Two officials, clearly recognizable by their red clothing, are responsible for managing the entire massacre. The first of them, sheltered to the left behind the low wall of the spina, is clearly visible: he simply takes care of raising the hatch so that the felines can access the arena. The other is not as visible, located to the right just above the podium, and his function is not so obvious until we see why he maintains an extended arm: he holds a burning cane with which he sets the martyrs on fire, one by one, committing dozens of public murders in a few minutes (fig. 5). We know that he moves to the right because the condemned, who are placed at equal intervals along the entire perimeter, burn in different phases of combustion as he moves away from them.

Once again, Gérôme has succeeded: both horrified and fascinated, we cannot stop looking. As much as we do not want to participate in the morbid show, its scenes provoke an almost hypnotic tension and intrigue very similar to those of the best suspense literature. As Emily Beeny has very insightfully noted,

All the arena paintings … [are] pictures about looking…. Gérôme was playing a far more subtle game. In these paintings the audience looks out at itself from within the frame, establishing a correspondence orchestrated by Gérôme with masterful irony. Contemporary viewers, in other words, experienced both a moral repulsion from and a narcissistic attraction to their painted counterparts…. Thus, though veiled in antique reference, Gérôme’s evocation in his arena pictures of a very modern experience of spectatorship was unmistakable.[23]

Role Models of Dignity

Agostino Caironi (Italian, 1820–1907), Famiglia di Cristiani, 1852, oil on canvas, 175.5 × 236.2 cm. Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, Milan, acc. no. 1980,58

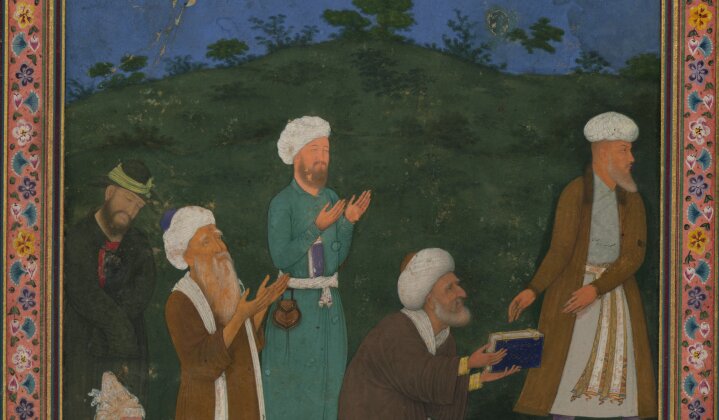

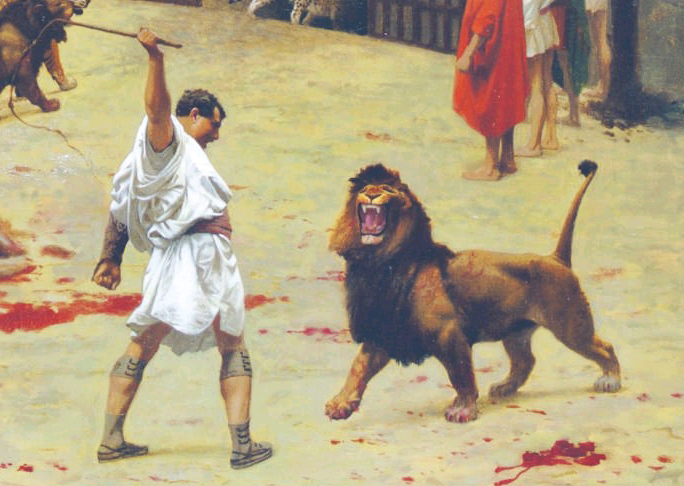

It is quite possible that for the realization of his painting Gérôme took into account other works with a similar theme such as those by Agostino Caironi (Italian, 1820–1907) (fig. 6) or Louis Félix Leullier (French, 1811–1882). Furthermore, it is probable that, during his trip to Russia and Northern Europe in 1853, he became familiar with works by Christian Slavic artists such as those of Konstantin Flavitsky (1830–1866), Aleksei Markov (1802–1878), or, above all, Fedor (Fyodor) Bronnikov (1827–1902).[24] The latter’s 1869 work Martyrs in the Arena (fig. 7) seems, in fact, to be a direct source for the group in The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer. However, the greatest inspiration must have come, at least for the definitive version, from the famous 1877 canvas by Polish artist Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902), The Torches of Nero (fig. 8). Human torches, for example, do not appear in the version of The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer preserved in Utah,[25] so it is likely that Gérôme did indeed add them after seeing the Polish painter’s canvas, exhibited in Paris in 1878.

Fedor Bronnikov (Russian, 1827–1902), Martyrs in the Arena, 1869, oil on cardboard, 16. 8 × 10 in. (42.7 × 25.5 cm). Museum of Local History, Shadrinsk

It is worth pausing briefly to further consider this painting as it seems to have had a direct influence on Gérôme’s later work. Siemiradzki had settled in Rome in 1872 and among the regular visitors to his workshop was his compatriot and great friend, the writer Henryk Sienkiewicz. Both were Polish artists and strong Catholics, and they shared a fascination with the Roman Empire, especially with the situation of the early Christians, whose resistance they saw as a counterpart to the struggle of the Catholic Polish people against Russian oppression. Their conversations and readings in those years led them to share a great interest in the martyrological accounts of ancient writers and, especially, again, by Tacitus. Sienkiewicz, in fact, had gone as far as to express,

I was most drawn to Tacitus as a historian. Dwelling on his Annals I was frequently tempted by the idea of presenting, in a literary form, these two worlds in which one was the all powerful governing machine of the ruling power and the other represented only a moral force.[26]

Henryk Siemiradzki (Polish, 1843–1902), The Torches of Nero, 1877, oil on canvas, 704 × 385 cm. National Museum, Krakow. acc. no. MNK II-a-1

All these debates resulted in Siemiradzki’s painting, which explicitly alludes to the passage of Tacitus in the signs hanging from each human torch (fig. 9) with the motto christianus incendiatur urbis generisque humani hostis,[27] as well as the famous novel by Sienkiewicz Quo Vadis (1896), which in chapter 21 the martyrdom of the Christians in the gardens of the Domus Aurea is narrated. Both the painting and the novel contributed in a decisive way to the fixation on what we could call the popular iconography of Christian martyrology in the modern imaginary and, in fact, Siemiradzki’s painting (as well as Gérôme’s) was used to illustrate numerous editions of Quo Vadis and to inspire early film versions.[28]

Detail of The Torches of Nero (the placard of the inscriptions based on Tacitus reads: CHRISTIANUS INCENDIATUR URBIS GENERISQUE HUMANI HOSTIS)

It should be noted, however, that the tone of the Polish artist’s work is quite different from that of Gérôme. In The Torches of Nero (as in Quo Vadis) martyrdom is seen as the logical consequence of a struggle worth sacrificing for. In The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer, however, that feeling does not exist at all. Although it shows us the “strong hearts” and the “unshakable faith” with which Christians assume their destiny, its true purpose is to highlight precisely the uselessness of that devoted suffering and the absurd injustice of all that gratuitous violence. It achieves this thanks to the blunt objectivity with which all the elements of the scene are treated, a distant coldness that should not be mistaken with the absence of emotional involvement.[29] If we condemned Gérôme for the absence of any moral highlighting in his paintings, we would not be understanding that the omission of any empathic pronouncement already supposes a moral position. If the viewer noticed that the painter intervenes too much, if they felt manipulated in any way, the effect that the artist intends to cause would vanish. Our fascination with the canvas comes precisely from its absolute—and extremely calculated—coldness. As his friend Eugéne Benson used to say, Gérôme always impresses us because his art is a work “without splendor, without impulse, without tenderness; intellectual, cold, true, clear, direct, intense.”[30]

Furthermore, as the painter himself recalled in his letter to Mr. Walters, the protagonists of the painting are not men, but beasts. An idea that, this time, seems to have come to the painter through the reading of his favorite source text for these subjects, the Rome au siècle d’Auguste, by Louis Charles Dezobry, where a passage from the third volume narrates, in the voice of a Roman of the first century, the following:

The hunting of animals by men is by far the most interesting…. It was held at the Circus Maximus, where I went to see it…. I focused almost exclusively my attention on a magnificent lion emerging from one of the sentry boxes near where I was. This excellent animal, brought from the forests of Mauritania, was four or five feet high and eight or nine feet long. Since he had not yet experienced the power of man and was used only to measure his strength against animals, he showed that confidence in his broad face, that fearless calm that gave him the habit of victory. Proud and aware of the terror he inspired, with slow majesty he directed his oblique steps towards the arena…. The deprivation of light caused in these noble animals a moment of surprise and awe.[31]

In fact, the presence of the felines, and especially the lion in the foreground, can be considered, as Dominique de Font-Réaulx states, “a kind of self-citation” of the artist himself.[32] Gérôme identified with the lion for many reasons: it was his second given name, a lion is traditionally shown with his patron saint Jerome, and it was also in the coat of arms of his native town Vesoul. In this way, and especially as the artist entered his old age, Gérôme found in the lion a kind of symbolic being with which he felt metaphysically connected to the point that he almost became, in the words of Fanny Field Hering, “a lion who painted other lions.”[33]

Furthermore, as an illuminating article by Albert Boime shows, a closer look at the painting reveals a striking absence of voracity on the part of the felines that in theory are about to attack the defenseless Christians.[34] The beasts emerge with prudent steps from their lairs and their leader appears in the center of the image, moving on its front legs almost “as gracefully as a ballerina.”[35] Its attention is drawn to the group of kneeling figures, which it examines with fascination but not aggressively. The other lion comes out of its dungeon with absolute calm while the tiger seems to smile benignly. One would almost say that the felines are about to snuggle up to the Christians to be gently petted, as, in fact, occurs in similar episodes such as those of Saint Eustace, Androcles, or Daniel,[36] as well as in the last scene of Gustave Flaubert’s The Temptation of Saint Anthony (1874),[37] a work contemporary with Gérôme’s work on this painting, where monstrous animals (including hybrid lions) move around the saint but leave him intact, thus anticipating his triumphant liberation. Similarly, in the painting’s scene we would expect an aggressive tension on the part of its protagonists, but instead we only find the meekness of the animals and the fortitude of the martyrs. The morbid cruelty of this scene does not come from them but, once again, from the spectators. Violence is not in the watched thing but in watching.

The Retreating Lions: The Compassion of the Lion-Human

If someone wonders about the fate of the martyrs and the crucified in The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer, they will get a macabre but clear answer in The Retreating Lions (fig. 3), which forms a thematic unit that completes the plot of the trilogy started with the Chariot Race twenty-five years before and, in fact, completes the entire series on the Roman ludi (games) that Gérôme had begun almost half a century before. This late work, painted shortly before his death, has been totally misunderstood, even in modern times, being branded as a “grisly piece of painting,”[38] “ultra-violent,”[39] “horrible,”[40] and “totally impossible to look at.”[41] However, it is a painting of enormous importance, which deserves a detailed analysis, free from prejudice.

In the painting, many characteristic details of Gérôme’s other arena paintings are repeated, as if the author wanted to emphasize that this is the work that definitively closes the series. The dismembered bodies dirty the sand with their blood, as was the case in Ave, Caesar, Morituri Te Salutant. The sinister spectacle is, as has been said, undoubtedly a continuation of the event that we can see in The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer, only this time the action is over. The setting has been moved from the Circus Maximus to the Colosseum, with an architectural panorama practically identical to that of Pollice Verso, although now the depopulated stands reveal the vomitoria (covered entrances) through which the last stragglers parade after attending the gloomy show. To the lions and the tiger have now been added felines of all species (panthers, leopards, etc.), which, satisfied after the slaughter, are gently guided to their cages. Above the human torches, completely charred now, appear halos, marking the status of martyrs that their protagonists have just achieved. For their part, the same two officials in red robes that already appeared in The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer lead those in charge of returning the pack to their respective cages, with the same cold and civil attitude.

Two excerpts from Rome au siècle d’Auguste approach the overall idea of the painting. Both refer to the moment after the massacre, but one focuses on what happens in the arena while the other refers to the stands:

Other shows are about to start, but first, like at the end of previous fights, the amphitheater is cleared of the corpses left in the arena. Some slaves remove dead or wounded bestiarii; other slaves, carrying in front of them harnessed mules, come to remove or, rather, to drag the animals.… I have not seen anything more terrible than leopards and panthers: the fierce air of these animals, their restless eye, their cruel gaze, their sudden movements, their roar louder and more hoarse than that of a rabid dog, caused terror even among the spectators.[42]

[…]

The crowd was leaving slowly, so difficult was it to separate their eyes from the arena. I was also one of the last in my stands. When I left it, I found myself almost alone in the building’s long circular corridors and its many stone staircases.[43]

However, and without wanting to deny the influence that, as on so many other occasions, Dezobry’s book may have had on Gérôme’s canvas, in this case it is highly probable that, as Laurence des Cars suggests,[44] the main reference point is some particularly macabre passage from Quo Vadis. In chapter 56 of the famous novel, for example, we read,

Amidst the howling and whining were heard yet plaintive voices of men and women: “Pro Christo! Pro Christo!” but on the arena were formed quivering masses of the bodies of dogs and people. Blood flowed in streams from the torn bodies. Dogs dragged from each other the bloody limbs of people. The odor of blood and torn entrails was stronger than Arabian perfumes, and filled the whole Circus.[45]

![Jan Styka (Polish, 1858–1925), Bloodthirsty Games in the Arena [illustration for the novel Quo Vadis] (Paris: Flammarion, 1904)](https://journal.thewalters.org/wp-content/uploads/Jan_Styka_-_Les_chretiens_aux_lions_-_1902-1.jpg)

Jan Styka (Polish, 1858–1925), Bloodthirsty Games in the Arena [illustration for the novel Quo Vadis] (Paris: Flammarion, 1904)

Various arguments support this hypothesis. Published for the first time in French only two years before the painting was completed, the success of Sienkiewicz’s novel was so overwhelming that, within a few months, it had a very successful adaptation in the theater of the Porte-Saint-Martin,[46] whose setting was directly inspired by Ave, Caesar, Morituri Te Salutant and Pollice Verso, a fact that demonstrates the early association of the novel with Gérôme’s universe. The first film adaptation, made by Ferdinand Zecca and Lucien Nonguet, was produced by Pathé studios also in 1901, shortly before the completion of this painting.[47]

![Jan Styka, The Torches of Nero [illustration for the novel Quo Vadis] (Paris: Flammarion, 1904)](https://journal.thewalters.org/wp-content/uploads/69372bec4eab5e0c405803f1394f6f97.jpg)

Jan Styka, The Torches of Nero [illustration for the novel Quo Vadis] (Paris: Flammarion, 1904)

On the other hand, we know that of the various translations, Ely Halpérine-Kaminsky’s was particularly successful (published in installments from 1901 to 1904). This edition is of particular interest to us because it was accompanied by dramatic illustrations by Polish painter Jan Styka (1858–1925) (figs. 10–11) which are very reminiscent of the scene in The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer, although it is impossible to determine the degree of influence they could have exerted on it.[48] Both works seem to strive not to spare the viewer any macabre detail, but they do so from an apparent technical and moral objectivity that only overwhelms them. In this sense, as Carlos Reyero says,

The picturesque appeal that the entire culture of the nineteenth century feels towards the presence of bloodied victims in pictorial images… is essential to the appreciation of interest in the painting, in a contradictory attempt to attract by producing dread…. The hypothetical ‘lesson in power’—truly terrible—is nothing more than a tragic pretext that overwhelms the viewer until it startles him.[49]

Detail of rebel lion, The Retreating Lions

Furthermore, if we assume that The Retreating Lions is the narrative continuation of The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer, we cannot help but think that the lonely lion who is now the only one who refuses to follow its companions (fig. 12) must be the same as the one who had first climbed up the ramp. And, being located right in the center of the composition, it seems clear that, despite being so far overlooked by critics, this scene must have accumulated some kind of emotional meaning for the artist. Again, the interpretive key seems to be the symbolic identification between Gérôme and the lion, an identification that, especially from the mid-1880s, reached such a point that it led the artist to start a very long series on lions and other solitary felines (fig. 13),[50] of which, in fact, both The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer and The Retreating Lions can be considered a version. In all these paintings, through the metaphor of the emancipated feline that inhabits vast desert landscapes, the artist projects his private fantasy onto the lion. And, although I do not know whether one should go to the extreme of interpreting these allusions as Freudian projections based on childhood dreams that seek to conquer and tame the animal (which in return will become the child’s special friend and protector),[51] it is clear that all of them are imbued with intense personal emotions. With his desert landscapes inhabited by lions, Gérôme confesses a melancholic longing for freedom and, surely, a high degree of vital unease with the oppressive bourgeois environment that constrained the Parisian society of the Third Republic, of which he was a distinguished part due to the important positions he held at the École des Beaux-Arts.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Two Majesties, 1883, oil on canvas, 27 1/4 × 50 3/4 in. (69.22 × 128.91 cm). Milwaukee Art Museum, Layton Art Collection, Inc., gift of Louis Allis, acc. no. L1968.82. Photo credit: John Nienhuis

In this painting, the lion, already satisfied, is rebellious, not because he wants to continue with the massacre but because he does not want to follow the guidelines of the man who threatens him with the stick. In its natural habitat, in a desert or on a wide plain, the lion would not have had to participate in such a degrading spectacle. He would simply have followed his instincts and hunted for food. The Romans have captured him, like his companions, to participate in a ruthless diversion that denigrates them, both animals and humans, so that, in a last act of dignity, he refuses to collaborate with his jailers. For all this we like to think that, although it goes against its animal nature, the lion as identified with the artist can also be interpreted as a sign of freedom and, ultimately, compassion.

[1] On the tradition of these paintings, see Joan Mut Arbós, “El pintor en la arena: Los ludi romanos en la pintura de historia decimonónica,” Goya: Revista de arte 369 (2019): 316–27.

[2] Ivo Blom, “Quo vadis? From Painting to Cinema and Everything in Between,” in Leonardo Quaresima and Laura Vichi, eds., La decima musa: Il cinema e le altre arti. Atti del VII Convegno internazionale di studi sul cinema (Udine: Forum, 2001), 281–96, at 285.

[3] Tomás Pérez Vejo, “Pintura de historia e identidad nacional en España” (PhD diss., Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2002), 510 and 529.

[4] The different chapters of this great work, whose full title was Rome au siècle d’Auguste, ou Voyage d’un Gaulois à Rome à l’époque du règne d’Auguste et pendant une partie du règne de Tibère, are written as if they were letters from a young traveler who traveled from Lutetia (ancient Paris) to Rome in the first century CE. In some way, therefore, it is part of a genre that had become very popular in the last decades of the previous century. That is a type of travel narrative that, structured from the guide of a literary voyager, leads the reader through various places in the ancient world while offering a wide range of antiquarian curiosities. The most famous exponents of this genre had been the Voyage pittoresque ou Description des royaumes de Naples et de Sicile (1873) by Jean-Claude Richard Saint-Non, the Voyage du jeune Anacharsis en Grèce (1788) by Jean-Jacques Barthélemy, and Les Voyages d’Antenor en Grèce et en Asie (1797) by Étienne Lantier. About this type of literature, see Philippe Antoine, “Un compagnon de voyage, le jeune Anacharsis,” in Jean-Claude Berchet, ed., Le Voyage en Orient de Chateaubriand (Houilles: Éditions Manucius, 2006), 137–41; and Joan Mut Arbós, “Sappho Recalled to Life by Music: Feminine Emotion and raison d’état in Neoclassical Napoleonic Painting,” Music in Art: International Journal for Music Iconography 43 (2018): 21–48.

[5] One of these versions, with slight variations, must be the sketch that is kept in the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, Salt Lake City, acc. no. 1988.014.001.

[6] Tacitus, Annales, 15, 44.

[7] Jean-Léon Gérôme, Lettre à Monsieur Walters, Paris, July 15, 1883, in Catalogue of Paintings (Baltimore: Walters Art Gallery, 1929), 38–39; see also Fanny Field Hering, The Life and Works of Jean Léon Gérôme (New York: Cassell, 1892), 243.

[8] William R. Johnston, “Gérôme—an Archaeologist?,” The Bulletin of the Walters Art Gallery 25, no. 7 (1973): 3.

[9] Cf. Jordina Sales-Carbonell, “Roman Spectacle Buildings as a Setting for Martyrdom and Its Consequences in the Christian Architecture,” Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology 1, no. 3 (2014): 8–21; and Maria Engracia Muñoz Santos, “Anfiteatros y ludi gladiatorii: Las fuentes clásicas e Hispania como ejemplo,” Saitabi: Revista de la Facultad de Geografía e Historia 62 (2013): 27–38.

[10] Cf. Monique Clavel-Lévêque, L’empire en jeux: Espace symbolique et pratique sociale dans le Monde Romain (Paris: Éditions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1984), 34. I am grateful to Professor Carme Bosch for her observation on this point.

[11] Presented to the Salon of 1859 as The Gladiators. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, acc. no. 1969.85.

[12] Considered as one of Gérôme’s masterpieces. Phoenix Art Museum, acc. no. 1968.52.A.

[13] Johnston,“Gérôme—an Archaeologist?,” 3.

[14] See, in general, Anna Carfora, I cristiani al leoni. I martiri cristiani nel contesto mediatico dei giochi gladiatorii (Trapani: Il pozzo di Giacobbe, 2009).

[15] Cf. Sales-Carbonell, “Roman Spectacle Buildings,” 11.

[16] Dominique de Font-Réaulx, “Dernières prières des martyrs chrétiens,” in Laurence des Cars, Dominique de Font-Réaulx, and Édouard Papet, eds., Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904): L’histoire en spectacle (Paris: Musée d’Orsay, 2010), 137–38, cat. 80.

[17] Richard Holland, Nero: The Man Behind the Myth (Gloucestershire: Sutton, 1998), 167, asserts, perhaps somewhat exaggeratedly, that this passage “has been subjected to more scrutiny than any other paragraph of secular historical writing that has come down to us from the ancient world.”

[18] Suetonius, Nero, 16, 5, scarcely dedicates a sentence to the torture of Christians: “Christians, a class of men full of new and dangerous superstitions, were delivered to torture”; and when he speaks of the burning of Rome, he does not even mention them (Nero, 38, 1).

[19] Tacitus, Annales, 15, 44.

[20] As noted by this journal’s editorial review board, knowing that Gérôme has Tacitus’s description in mind, the tracks in the sand maybe could be read as the wheel marks made by Nero as he circled in his chariot.

[21] In fact, he seems to have struggled with their placement, especially in the light of the study in Utah; thanks also to the editors of this journal for that observation.

[22] Marc Gotlieb, “Gérôme’s Cinematic Imagination,” in Scott Allan and Mary Morton, eds., Reconsidering Gérôme (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010), 54–64, at 54.

[23] Emily Beeny, “Blood Spectacle: Gérôme in the Arena,” in Allan and Morton, Reconsidering Gérôme, 40–53, at 44.

[24] All references to these works are in Mut Arbós, “El pintor en la arena.”

[25] See note 5.

[26] Henryk Sienkiewicz, letter dated 1901, cited in Bonhams, 19th Century Paintings, 23 March 2004, lot 44, which is a later copy of this painting by the artist.

[27] “Christian burned for being an enemy of the city and the human race.”

[28] For an overview, see Blom, “Quo vadis?” See also, Pérez Vejo, “Pintura de historia e identidad nacional en España,” 510–22.

[29] The “amorality” or the excess of coldness was one of the typical accusations against the work of Gérôme; see Eugéne Benson, “Jean-Léon Gérôme,” The Galaxy (1866): 581–87; Henry Trianon, “Salon de 1847,” Le correspondant 18, no. 8 (1847): 224; John House, “History Without Values? Gérôme’s History Paintings,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 71 (2008): 261–76, at 271; Hélène Jagot, “La peinture néo-grecque (1847–1874): Réflexions sur la constitution d’une catégorie stylistique,” (PhD diss., Université Paris, 2013), 121; and Scott Allan, “Introduction,” in Allan and Morton, Reconsidering Gérôme, 1–6, at 4.

[30] Benson, “Jean-Léon Gérôme.”

[31] Dezobry, Rome au siècle d’Auguste, 3: 549–56.

[32] Font-Réaulx, “Dernières prières des martyrs chrétiens,” 138, cat. 80.

[33] Field Hering, The Life and Works of Jean Léon Gérôme, 37; and Jack Perry Brown,“The Return of the Salon: Jean Léon Gérôme in the Art Institute,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 15 (1989): 154–81, at 157.

[34] Albert Boime, “Jean-Léon Gérôme, Henri Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy and the Academic Legacy,” The Art Quarterly 34 (1971): 3–28, at 14. Despite the authority of its author, this suggestive text has inexplicably gone unnoticed by critics; not even Gerald Ackerman’s Jean-Léon Gérôme: Monographie révisée et catalogue raisonné mis à tour (Paris: ACR, 2000) or Hélène Jagot mention it in their general bibliographies.

[35] Boime, “Jean-Léon Gérôme, Henri Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy,” 14.

[36] Referenced in the Legenda Aurea, 161, in Aulus Gellius, Noctes Atticae 5, 14, 10, and in the book of Daniel 6:1, respectively. Gérôme also painted an Androcles and the Lion, 1902, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, acc. no. 5498.

[37] Boime, “Jean-Léon Gérôme, Henri Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy,” 15.

[38] David Scott Watson, “Jean Leon Gérôme (1824–1904): A Study of a Mid-Nineteenth Century French Academic Artist” (PhD diss., University of British Columbia, 1977), 111.

[39] Laurence des Cars, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), 140, cat. 81.

[40] Gerald Ackerman, Jean-Léon Gérôme, 286.

[41] Guy Cogeval,“Une beauté exacte et perverse,” in des Cars, Font-Réaulx, and Papet, eds., Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), 11–15, at 14.

[42] Dezobry, Rome au siècle d’Auguste, 3: 549–56.

[43] Dezobry, Rome au siècle d’Auguste, 3: 582.

[44] Des Cars, 140, cat. 81.

[45] Henryk Sienkiewicz, Quo Vadis?, trans. Jeremiah Curtin (London: J. M. Dent, 1897), 450.

[46] Due to Émile Moreau; see Maria Kosko, Un “Best-Seller” 1900: Quo Vadis? (Paris: Librairie José Corti, 1960), 43.

[47] Des Cars, 140, cat. 81. See also, in general, Eric Moormann, “Questa Rovina viva: Pompei nella letteratura del secondo ottocento,” in Eugenia Querci and Stefano De Caro, eds., Alma Tadema e la nostalgia dell’Antico (Milan: Electa, 2007), 124–37.

[48] Styka was chosen by the Flammarion publishing house despite the fact that Sienkiewicz had explicitly stated that he wanted his book to be illustrated by Piotr Stachiewicz; see Kosko, Un “Best-Seller” 1900, 43. Stachiewicz went on to make twenty-two plates about the novel to be reproduced as postcards, a series that, considered lost for many years, has recently reappeared in the American antiquarian market.

[49] Carlos Reyero, La pintura de historia en el siglo XIXI en España (Madrid: Cátedra, 1989), 208.

[50] Ackerman, Jean-Léon Gérôme, 320, cites a long list of paintings with the lion as the symbolic protagonist.

[51] Boime, “Jean-Léon Gérôme, Henri Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy,” 8–16.