Unidentified Chinese artist, Pair of Revolving Gourd-Shaped Vases, China (Jingdezhen), reign of the Qianlong emperor (1736–1795), porcelain, overglaze enamels, and gilding, H: 16 5/16 in. (41.4 cm). Acquired by William T. or Henry Walters, before 1896, acc. nos. 49.2180 and 49.2181

Many of the ceramics made during the latter half of the eighteenth century in China demonstrate a spirit of creativity, experimentation, and innovation that was encouraged under the aesthetic direction of the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736–1795) and the inventive genius of Tang Ying (唐英, 1682–1756), superintendent and creative supervisor of the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen (in Jiangxi Province). Revolving vases were one such innovation. Commonly referred to as a “slip vase” or “vase with revolving inside” (zhuanxin ping 轉心瓶), the inside of the vase could be rotated by hand independent of the stationary outside walls of the vase. The Walters Art Museum has a pair of identical revolving vases, each in the shape of a double gourd (fig. 1). Scholars have researched the records in the imperial archives for any mention of the creation of revolving vases. We can glean several things from these records: revolving vases were expensive to make; they involved a long production process; they demanded meticulous craftsmanship in every stage of production; these vases were commissioned by Emperor Qianlong primarily for special occasions; few examples have survived to the present day—even rarer are a matching pair of revolving vases, like the Walters’ pair; and finally, production of revolving vases appears to have been restricted to the Qianlong reign, as revolving vases with layered openwork were made in response to the emperor’s insatiable demand for novelty. The Walters’ pair of revolving vases prove to be a technical marvel in auspicious form.

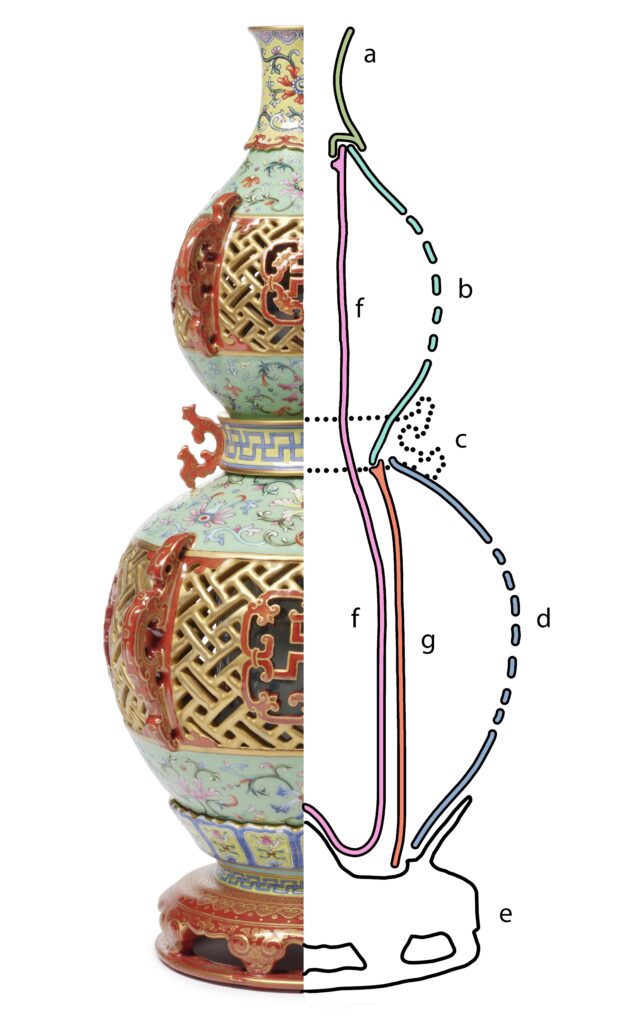

Revolving vases incorporate movement by nesting two vases and turning the interior vase independently of the exterior. In its simplest form, a revolving vase is constructed of three parts—a decorated interior vase and an exterior vase with an openwork, or reticulated, design, itself created in two parts so it can be opened and fitted around the interior vase. This construction creates the illusion that the interior vase and exterior vase were formed out of one piece of clay rather than the two vases made separately and assembled post-firing. The movement is often accomplished by turning the exterior neck of the vase which would engage the interior vase, through hidden mechanisms. As the interior vase is rotated, its decoration also rotates and can be viewed through openings or carvings on the exterior vase.[1] It is rare to find detailed documentation of the construction of these vessels and their hidden mechanisms, so they maintain the same sense of mystery today when only seen in photographs and display cases.[2]

The Walters’ pair of revolving vases exhibits a more complex technical design than the simple three-part construction described above. They also express blessings through their decoration and double-gourd form. Each vase of this pair is constructed from multiple parts. Each part was individually formed, decorated, and fired multiple times requiring incredible technical mastery to maintain the fit and avoid distortion in these complex assemblages. Unfortunately, past damage and restoration had limited our understanding of these complex vases because neither can be fully disassembled or rotated as intended. It is only through X-radiography and a careful examination of the individual parts that we can begin to understand the vases’ original construction and internal components.

First of all, several extant examples of Qianlong-period revolving vases are in the form of one gourd; less numerous are the double-gourd vases, like the Walters’ examples.[3] The gourd form is itself meaningful in Chinese culture. The bottle gourd is considered an auspicious vessel because it absorbs evil vapors of the universe. This belief may relate to the long-standing function of the bottle gourd to hold medicine—it eventually evolved into a symbol representing doctors of traditional Chinese medicine. In addition, immortals and legendary Daoist figures are believed to use bottle gourds to carry medicines with magical power. The bottle gourd also symbolizes good fortune since the Chinese pronunciation of “bottle gourd” (hulu 葫蘆) is similar to the words for “blessings” (fu 福) and “salary” (lu 禄) combined.[4]

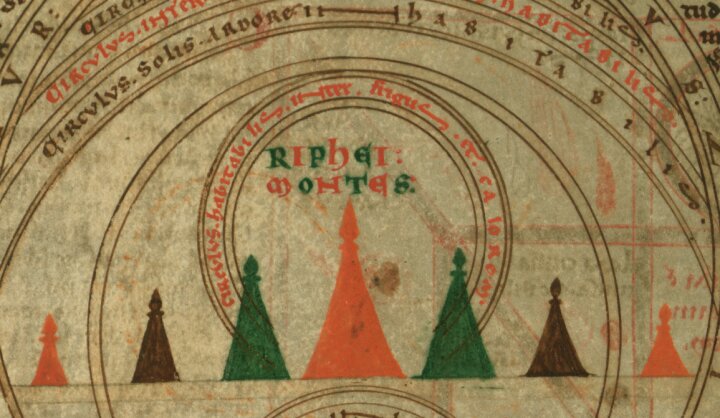

Diagram showing individual parts that comprise the Walters Art Museum’s vases, acc. nos. 49.2180 and 49.2181

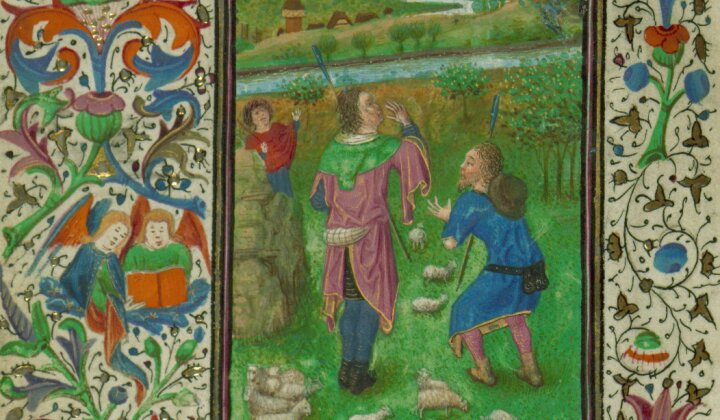

As the pair of vases appear to be originally constructed in the same manner, this description will focus on the less heavily restored example (acc. no. 49.2180) for clarity. The exterior vase consists of two separately constructed globular sections—the top gourd and the bottom gourd (fig. 2, parts b and d, respectively)—with the join covered by a separate collar that rests on the exterior (part c). The floral decoration covering each exterior vase’s top and bottom gourds depicts exuberant blossoms and foliate scrolls, all arrayed over a turquoise ground incised with a pattern that has been described variously as meander (a variety of fretwork), scrollwork, or arabesques.[5] The center of each gourd has a gilded openwork band punctuated by four red swastikas. Each gourd is also separated into four equal parts by curly cloud-like projections. The swastika is a significant motif (fig. 3). Today the swastika is a cultural symbol of white supremacy, but before the Nazi Party commandeered it in the twentieth century, for thousands of years cultures across the globe used the symbol to represent prosperity. The auspicious swastika was introduced into China from India with Buddhism in the early sixth century. In China, it is pronounced wan 卍, a homophone of the Chinese word for the equally favorable concept of “ten thousand” or “myriad” (wan 萬).[6]

Detail of the revolving interior vase with bats-and-clouds design and the swastika motif on the exterior gourd wall, One of a Pair of Revolving Gourd-Shaped Vases, acc. no. 49.2180

The interior vase (part f) is decorated with a design of red bats flying among blue clouds (fig. 3). The design of bats-and-clouds is one of the more common decorations seen in extant examples of revolving vases. The design is auspicious. The word “bat” (fu 蝠) is a pun for “blessings” (fu 福), and “cloud” (yun 雲) has the same pronunciation as “fortune” (yun 運). Combined, bats and clouds express the blessing of “May you have good fortune or luck” (fuyun 福運).[7]

Base of the vase with notches and raised bump, or conical form, One of a Pair of Revolving Gourd-Shaped Vases, acc. no. 49.2180

The neck of the exterior vase (part a) is a separate piece that is inserted into the exterior top gourd and registers inside the nested interior vase. This exterior assemblage sets into the base (part e) which has a raised and flared outer rim with an unglazed ring immediately on the inside edge, followed by a recessed ring with angled “stops” or notches, and a raised conical form in the center (fig. 4). The bottom edge of the exterior bottom gourd (part d) rests just inside the rim, while the conical form connects to the divot, or concave bottom, of the interior vase to facilitate the movement, as seen in the digital X-radiograph (fig. 5).[8]

Digital X-radiograph showing the interior components, One of a Pair of Revolving Gourd-Shaped Vases, acc. no. 49.2181

Although parts of the interior vase are visible from the bottom when removed from the base (fig. 6), we see an extra component that is unexpected: the cylinder between the exterior vase and the interior vase. X-radiography provides the following clarification. Looking from the outside inwards, the interior vase appears to be one continuous piece from the top gourd to the bottom gourd, because the bats-and-clouds design appears unbroken. However, the lower section of the interior vase is actually covered by a separate cylinder (fig. 2, part g) that has a matching bats-and-clouds design. The matching design contributes to the appearance of one solid interior vase, but it is actually constructed of two separate but nested parts—an innermost narrow-necked bottle with a divot in the base, what we call the interior vase (part f), and a tapered-neck cylinder that covers the lower half of the interior vase (part g). The interior vase is only visible through the reticulated top gourd; the cylinder, which covers the lower half of the interior vase, is visible through the reticulated bottom gourd, and the cylinder does not move. The cylinder is held in place by the recessed ring on the base. The angled notches or stops on this recessed ring correspond to two equally spaced areas of repair on the bottom of the cylinder (fig. 6). These repairs were likely tabs that slotted into the notches, allowing the cylinder to slide into place and stop the cylinder from rotating while the interior vase, which rests on the conical form of the base, is able to turn independently when the exterior neck (part a) is rotated. The addition of the stationary cylinder hiding the lower half of the interior vase means that when the exterior neck is rotated, we see only the top half of the bats-and-clouds design spin through the reticulated top gourd; the bottom half of the same design remains stationary when viewed through the bottom gourd.

Detail of the bottom of the vase assemblage showing the exterior vase, the cylinder with the two repaired areas along its rim, and the interior vase with divot, One of a Pair of Revolving Gourd-Shaped Vases, acc. no. 49.2180

Herein lies the innovation of the Walters’ revolving vases as compared to the majority of extant examples: the Walters’ revolving vases have an additional mechanism that allows only one half of the interior vase decoration to rotate rather than having the entire length of the decoration move. To be clear, even with X-radiography, the density of the various pieces that meet at the join under the collar (fig. 2, part c) makes it difficult to define the boundaries of each piece of construction with any certainty. However, based on what we know of extant examples, and what we can see of the internal mechanism of the Walters’ vases, we propose that the intention for the Walters’ vases was precisely to have only the top portion of the bats-and-clouds design in motion. It may seem like a small technical variation to the revolving vase design, but it may have been enough of a marvel to delight the Qianlong emperor.[9] It arguably makes the Walters’ revolving vases a standout among extant pieces of their kind.

[1] The following are a few extant examples of revolving vases: Revolving Vase with Swimming Fish Decoration (National Palace Museum, Taipei); Revolving Gourd Vase (Philadelphia Museum of Art); and Porcelain Vase Decorated in Fencai Enamels against a Yellow Ground, with Rotating Interior and Openwork Eight Trigram and Ju-i Motifs (National Palace Museum, Taipei).

[2] To see how a revolving vase moves, view this example from the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ij935VhPos8. A diagram of the nested vase construction of a revolving vase is also published in Zhu Jiajin, Treasures of the Forbidden City (Middlesex, England; New York: Viking, 1986), 182.

[3] A particularly rare example appeared at a Sotheby’s auction in 2022: a revolving vase with three different gourd sections that rotate against each other (Sotheby’s, 23 March 2022, New York, Lot 269).

[4] Terese Tse Bartholomew, Hidden Meanings in Chinese Art (San Francisco: The Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, 2006), 61.

[5] Dany Chan, “‘Adding Flowers on Brocade’: Shared Aesthetics of a Qianlong Porcelain and Rococo Textiles,” Orientations 47, no. 6 (September 2016): 64–67.

[6] Bartholomew, Hidden Meanings in Chinese Art, 225.

[7] Bartholomew, 22.

[8] This X-radiograph is of the other vase (acc. no. 49.2181).

[9] The exterior vase parts are all independent. Although they are not locked into place and can move, they were likely never intended to move. This capacity for movement is most likely unintended and solely a part of the assembly method, as there is otherwise no obvious mechanism to easily create the revolutions of the exterior parts.