Provenance, or the chronology of the ownership, custody, or location of a historical object, is an increasingly popular topic in the news, but researching and updating the provenance of any object to share publicly, such as on museum’s collections webpage, is always a work in progress. Museums strive to research, record, and share provenances for all objects, yet the format used is often difficult to parse and can obscure the very long and sometimes complicated histories of objects. The format for an artwork’s provenance statement at the Walters Art Museum is adapted from the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) Guide to Provenance Research.[1] The provenance statement is meant to be made up of brief, regularized “provenance episodes” that record each known owner, the city or region in which that individual was located, the date and mode of acquisition of the artwork, and the details of any known sales or auctions. The episodes are listed in chronological order, from oldest to most recent, with other information, such as footnotes and inventory numbers, included as appropriate, usually placed in square brackets ([]). The punctuation between the episodes is important, with semicolons (;) indicating direct transfer, while a period (.) is placed between two owners when a direct transfer did not occur or is not known to have occurred.

A lot of information is packed into this short format, but the online provenance statement cannot convey all the knowledge that museum staff have about the ownership history of an object, which can sometimes span centuries. A longer narrative text, whether it is a few paragraphs or a longer work such as an article, can be needed to tell the full story of an object’s history. For instance, a glance at the provenance of an Intaglio with Helios Set in a Ring, which is one of the 101 carved gems from the Marlborough collection presently in the Walters Art Museum, presents an intimidatingly long provenance text describing the journey of this gem from 1638 to the present;[2] happily, the provenances of the entire collection of gems and cameos once owned by the fourth duke of Marlborough are the subject of a book by classical archaeologist and art historian John Boardman.[3] The Rubens Vase, which once belonged to the artist Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), is another object at the Walters Art Museum whose centuries-long provenance is summarized online by a substantial provenance statement, which has also been expanded on in a lengthy article by Marvin Chauncey Ross, curator at the Walters from 1934 to 1952.[4] These kinds of expanded narratives are unfortunately more often the exception than the rule.

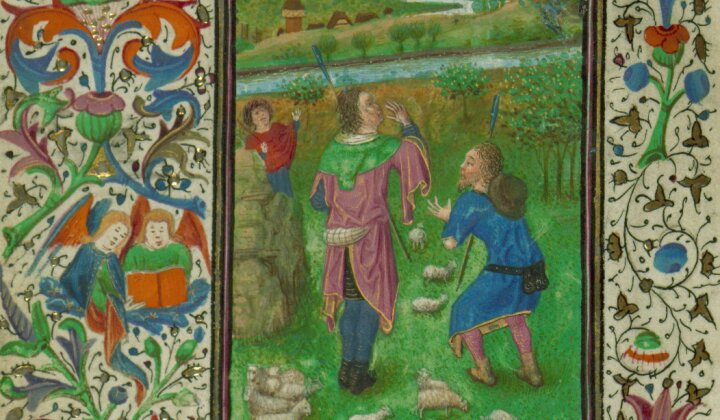

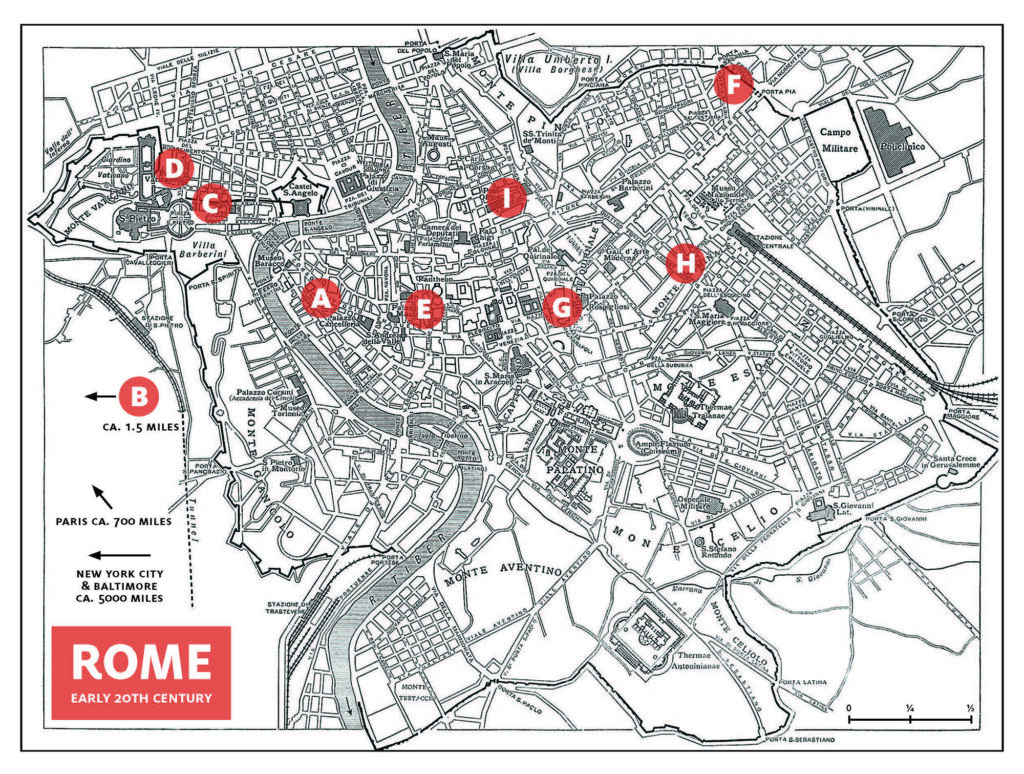

Map of the city of Rome with locations mentioned in text

A. S. Stefano Piscinula (destroyed)

B. Villa Carpegna (to the west of the area shown on this map)

C. Palazzo Accoramboni-Rusticucci (destroyed)

D. Warehouse used by Marcello Masseranti (destroyed?)

E. Palazzo Lante

F. Licinian Tomb (no longer accessible)

G. Palazzo Campanari

H. Palazzo Maraini?

I. Gallery of Marinangeli and Pirani (Palazzo Gresham)

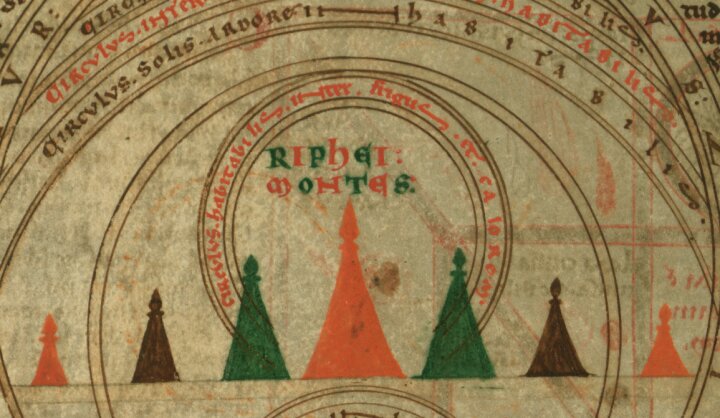

For centuries, it has been a fortunate tendency of antiquarians, that is, people who study or have an interest in ancient things, to make records of carved stones in the city of Rome. Stones with inscribed texts were commonly copied, as the text can be recorded without needing to employ any artistic talent. Carved stones without text, from sculptures to sarcophagi, have also been featured in sketchbooks and early print books with illustrations, and published notices of excavated finds are also a well-established feature of antiquarian literature, particularly during the nineteenth century. This note will expand upon the provenance statements of three carved Roman marbles from their first reported locations in the city of Rome to their present location in the collection of the Walters Art Museum (fig. 1).[5] My aim is both to give examples of the provenance format used at the Walters and to highlight the additional information known about the histories of these objects that cannot be included in a highly abbreviated provenance statement. The modern histories of these three objects highlight how different elements of provenance research build on each other. Knowing the name of a former owner can help the researcher identify the location where an object was kept; conversely, if the location (sometimes the exact street address) where it was stored and the date it was there are both known, the researcher may be able to draw conclusions about who the owner was at that time. But the provenance statement needs to be updated as more information becomes available and new discoveries require corrections to the statement. The three examples were chosen because each has a long history, each has been part of my recent research at the museum, and because their locations within and outside the city of Rome add to the stories that can be told about the objects as well as the art market itself.

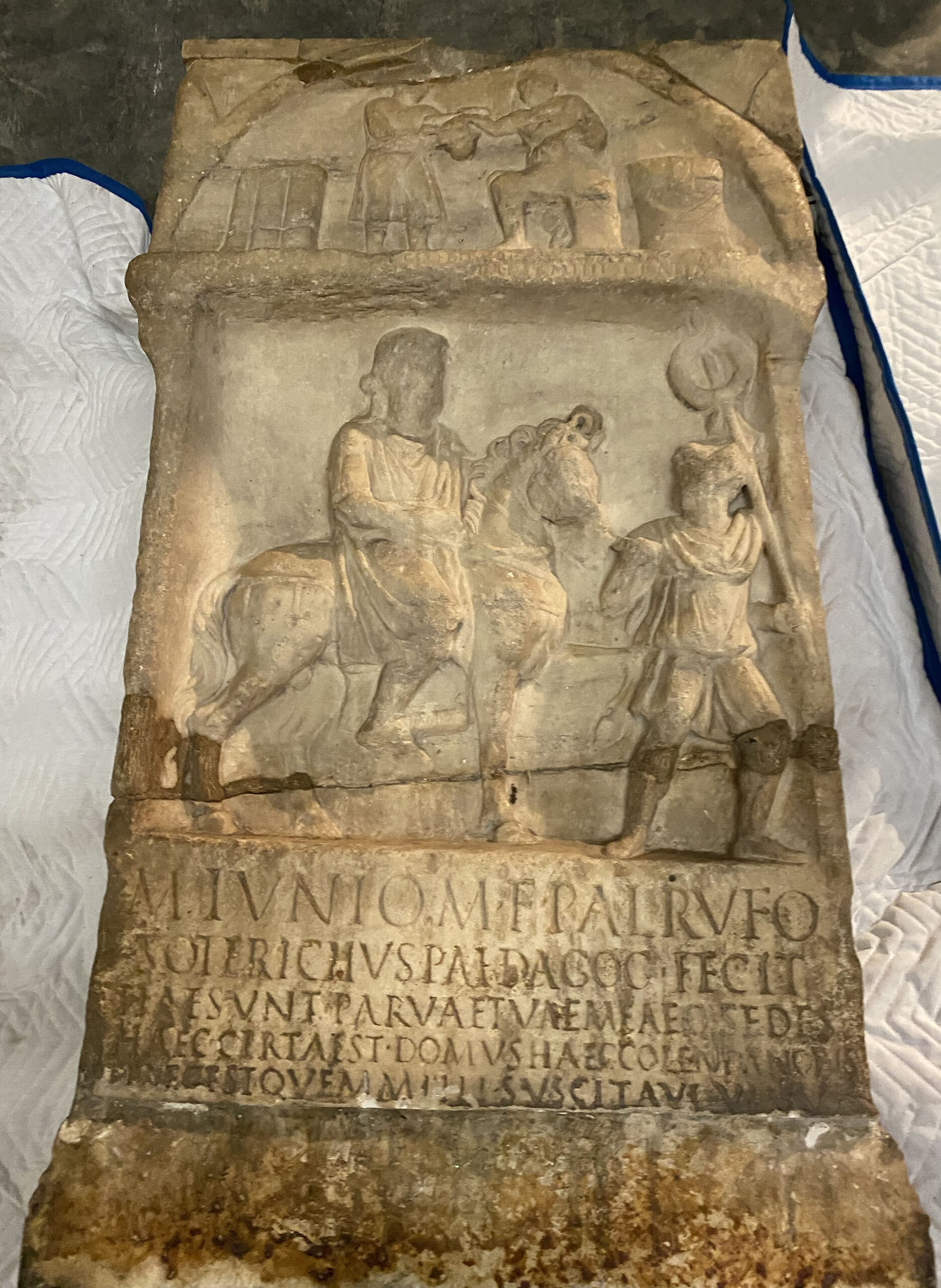

Altar Dedicated to Marcus Iunius Rufus by his Tutor Soterichus, acc. no. 23.18

In the mid-second century CE (ca. 130–160 CE), Soterichus, an enslaved tutor (paedagogus), dedicated a highly decorated funerary altar to his student, Marcus Iunius Rufus. There are two scenes on the front of the altar: one showing a student and teacher that may represent Marcus Iunius Rufus and Soterichus and the other showing a servant or enslaved man guiding a horse and rider. A fragmentary poem is inscribed on the thin rectangular band that separates the images,[6] and a larger epitaph and poem are inscribed below the equestrian scene.[7] On one side of the altar is a comedy mask, and on the other is a tragedy mask, referring to the literary studies of Marcus Iunius Rufus and Soterichus. The back is undecorated.

Provenance[8]

Commissioned by Soterichus for Marcus Iunius Rufus, Rome, 2nd century CE [recorded and illustrated by Pirro Ligorio at S. Stefano (Piscinula), ca. 1553–1568]. Cardinal Gaspare Carpegna, Rome, by 1699, [mode of acquisition unknown]. Don Marcello Massarenti, Rome, by 1894, [mode of acquisition unknown] [marble no. 15]; Henry Walters, Baltimore, 1902, by purchase; Walters Art Museum, 1931, by bequest.

Commissioned by Soterichus for Marcus Iunius Rufus, Rome, 2nd century CE [recorded and illustrated by Pirro Ligorio at S. Stefano (Piscinula), ca. 1553–1568].

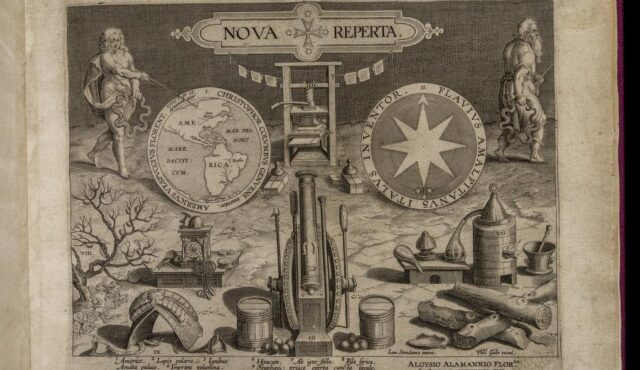

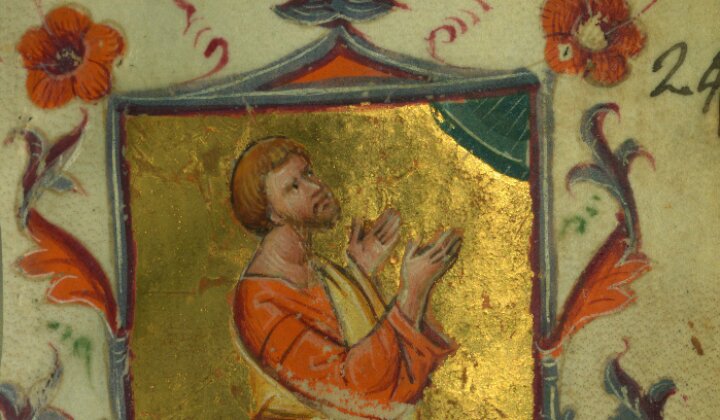

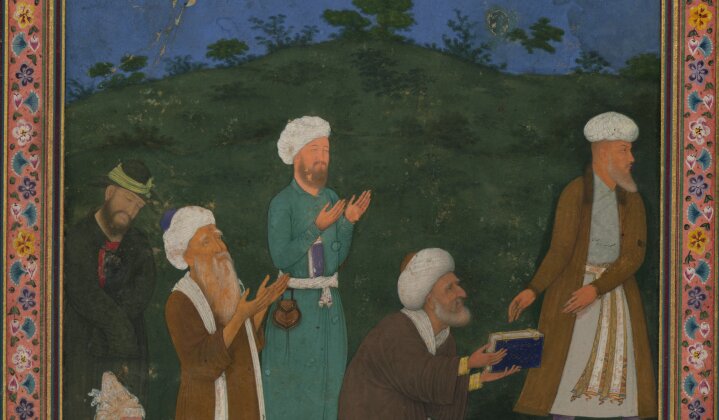

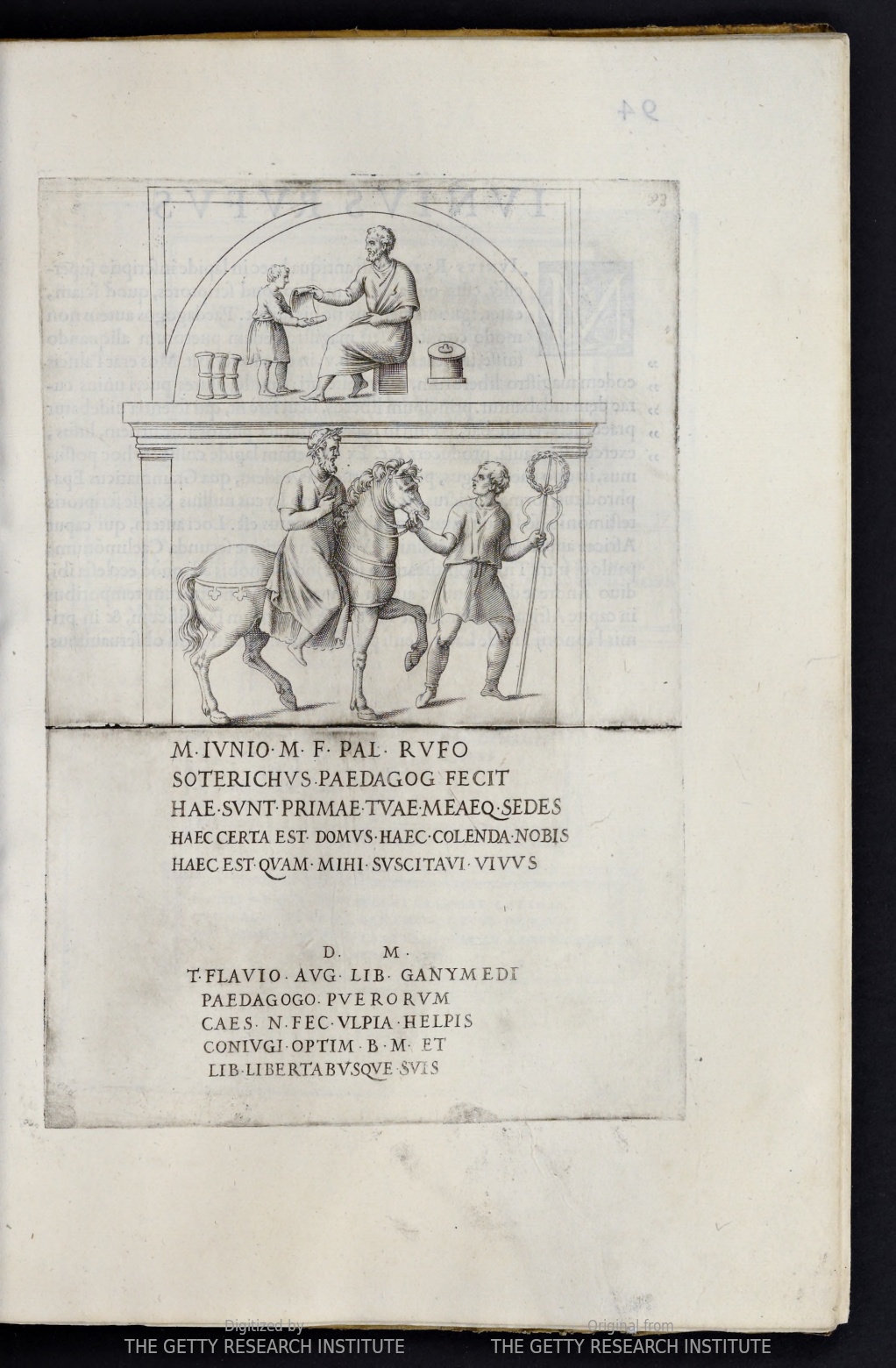

A sixteenth-century record of the Altar Dedicated to M. Iunius Rufus by his Tutor Soterichus, now Walters Art Museum acc. no. 23.18, from Fulvio Orsini, Imagines et elogia virorum illustrium et eruditor ex antiquis lapidibus et nomismatibus (Rome: Ant. Lafrerij formeis, 1570), 93

The person who commissioned an artwork is sometimes listed as the first owner, therefore Soterichus can appear as the first owner in the provenance statement. Although the place of discovery is not usually included in a provenance statement, it is added here because this first recorded sighting and placement of the altar is significant and because entering this information in the provenance field of our database makes it easier to find, including through internet searches. Sketches of the altar survive in manuscripts created by antiquarians Pirro Ligorio (1513–1583)[9] and Giovanni Antonio Dosio (1533–1611).[10] Cassiano dal Pozzo (1588–1657) included it in his Paper Museum, basing his drawing on Ligorio’s.[11] Fulvio Orsini (1529–1570) included this altar in his 1570 publication Imagines et elogia virorum illustrium et eruditor ex antiquiquis lapidibus et nomismatibus (fig. 2). The published image is thought to be based on another drawing of it in the Codex Ursinianus, a sixteenth-century sketchbook once owned by Orsini and now in the Vatican Library, which may itself be a copy after Ligorio’s sketch.[12] It is difficult to pinpoint the year in which Ligorio saw the altar, but the Census of Antique Works of Art and Architecture Known in the Renaissance estimates that Ligorio made the sketch sometime between 1553 and 1568.[13] Ligorio noted that when he saw it, the altar was at the church of S. Stefano, near the church of S. Lucia della Chiavica (fig. 1, location A).[14] The church of S. Stefano is no longer extant but was located on the present Via dei Banchi Vecchi between the Vicolo Cellini and the Via dei Cartari. In antiquity, this area was in the western section of the Campus Martius, or Field of Mars, but the ancient buildings and activities in this location are not terribly well known.[15]

Cardinal Gaspare Carpegna, Rome, by 1699, [mode of acquisition unknown].

The altar can be traced from the location recorded in the sixteenth century into the collections displayed at the Villa Carpegna by 1699, when a transcription of the text was published by the antiquarian Raphael Fabretti.[16] The word “by” is used before the date to indicate that it was in that collection “by or before” 1699, but there is currently no information available to indicate the exact year in which it arrived there. The Villa Carpegna and the artworks within were owned by noted art collector Cardinal Gaspare Carpegna (1625–1714). The Villa Carpegna is a large property and park to the southwest of Vatican City (fig. 1, location B). There is no record of how the altar came to the Villa Carpegna, whether it was a purchase, a gift, or if the cardinal had some authority to remove it from the grounds of S. Stefano. The altar was still in the Villa Carpegna in the late nineteenth century when the volumes of Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL) that focus on inscriptions from the city of Rome were under preparation.[17]

Don Marcello Massarenti, Rome, by 1894, [mode of acquisition unknown] [marble no. 15]; Henry Walters, Baltimore, 1902, by purchase; Walters Art Museum, 1931, by bequest.

The condition not long after it was acquired from the Massarenti collection. Unidentified Roman sculptor, Altar Dedicated to M. Iunius Rufus by his Tutor Soterichus, Italy (Rome), 2nd century CE, marble, size when acquired: 37 1/2 × 22 1/4 × 18 in. (95.3 × 56.5 × 45.7 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, acquired by Henry Walters with the Massarenti Collection, 1902, acc. no. 23.18

Along with three other inscribed altars from the Carpegna collection,[18] this altar had become part of the collection of Don Marcello Massarenti (1817‒1905) by 1894, when it was published in the English-language catalogue of Massarenti’s collection as marble no. 15 (fig. 3).[19] Massarenti, a Vatican official who worked as an almoner or sub-almoner for Popes Leo XIII and Pius X, amassed a personal collection of approximately 1,700 artworks and antiquities in the late nineteenth century. We do not know in what year the altar left the Carpegna collection nor when or how Massarenti acquired it, just that both of these things must have been done by 1894. When available, inventory numbers from previous collections can be included in the provenance statement. In this case, the inventory number is “marble no. 15.” The first image of the altar at the Walters (fig. 3) shows the numeral “15” stenciled on the altar itself near the top. The inventory numbers were stenciled directly on most if not all of the ancient marble objects in the Massarenti collection, which has sometimes been useful for matching the objects with their early descriptions. Much of Massarenti’s collection was stored in Rome at the now-destroyed Palazzo Accoramboni at Piazza Rusticucci 18, at the border between Rome and Vatican City (fig. 1, location C), but German archaeologist Ludwig Pollak noted, in his account of a visit to the Massarenti collection, that the marbles were kept in a warehouse at the Via di Porta Angelica 50 (fig. 1, location D), probably within the walls of Vatican City.[20] Henry Walters purchased the entire Massarenti collection in April 1902, and the collection was loaded on his ship that July and exported to New York. From 1902 to 1907, most of the Massarenti collection was stored on the eighth floor of the Parker Building, New York, while Henry Walters built his gallery on Charles Street in Baltimore (the present “Palazzo” building of the Walters Art Museum campus), but the marbles were not stored at the Parker Building because they were deemed to be too heavy for that space.[21] We do not yet know where the marbles were stored from 1902 to 1907. The entire Massarenti collection, including the marbles, was moved to Baltimore in the fall of 1907. Henry Walters bequeathed the altar with the rest of his collections in Baltimore to the City of Baltimore on his death in 1931. The altar is currently in storage; it has not been on exhibit since the 1990s, and the restored top and bottom have been removed from the ancient portion of the altar (fig. 4). The altar’s precise locations after it was in Massarenti’s collection and before it came to Baltimore are not the type of information that would be included in a provenance statement, which gives a general location for each owner rather than the object. But the locations give a sense of the wealth of the owners like Marcello Massarenti, Henry Walters, and even Gaspare Carpegna, who could afford to live at and store artworks in desirable locations.

The current state of the Altar Dedicated to M. Iunius Rufus by his Tutor Soterichus, acc. no. 23.18, with the restored top and bottom removed

Torso of Artemis with Head of Aphrodite, acc. no. 23.82

The short dress (chiton) and remnants of a quiver on the back identify this carved marble torso as belonging to a statue of Artemis (Roman Diana), goddess of the hunt. The head, although also ancient, once belonged to a statue of Aphrodite (Roman Venus); therefore the head and torso do not belong together. The marble components were carved separately in the first century CE, copying Greek originals from the fourth to second-centuries BCE. It was common practice in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to combine ancient fragments or re-create missing parts of statues to make them more aesthetically pleasing, creating a pastiche. An object is described as a pastiche if it is made up of parts of more than one object. The different parts can be from different times, that is, one section could be ancient and another modern, or they could be from separate objects dating to the same time. In its present state, this statue is a pastiche made up of ancient components.

Provenance

Lante Montefeltro della Rovere family, Rome, by 1778, [mode of acquisition unknown]. Comte James Alexandre de Pourtalès-Gorgier, Paris, by 1841, [mode of acquisition unknown]; sale, Catalogue des objets d’art qui composent les Collections de feu M. le Comte de Pourtalès-Gorgier, Paris, 21 March 1865, p. 16, lot 56. Henri Daguerre, Paris, by 1921, [mode of acquisition unknown]; Joseph Brummer, Paris and New York, 1921, by purchase [Brummer inv. no. P220]; Henry Walters, Baltimore, 1922, by purchase; Walters Art Museum, 1931, by bequest.

Lante Montefeltro della Rovere family, Rome, by 1778, [mode of acquisition unknown].

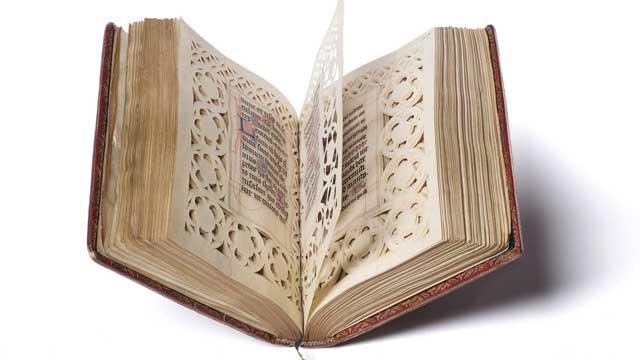

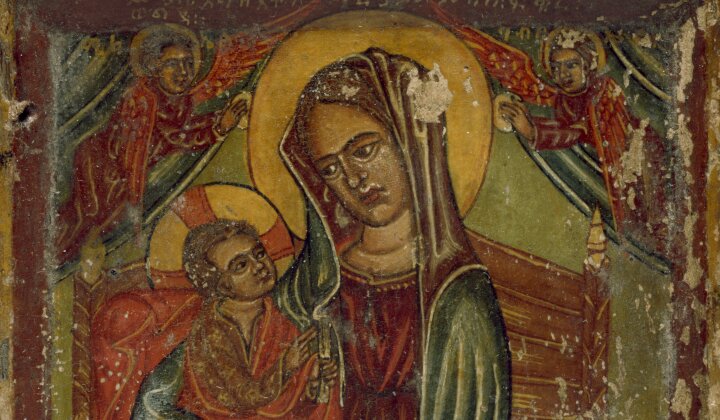

An eighteenth-century record of the statue of “Diana” from the Palazzo Lante, now Walters Art Museum, acc. no. 23.82, from Calcografia di Roma (Rome: Giovanni Battista Canetti, 1779), 3: pl. 20

In 1778, an etching of the statue, which is described as depicting the goddess Diana, was published in La ville de Rome and noted to be in the Palazzo Lante.[22] The next year the etching was republished in Calcografia di Roma, and the statue is said more precisely to be in the courtyard of the Palazzo Lante (fig. 5).[23] Knowing the name of the building the statue was in allows us to reconstruct “the owner” of the statue as the Lante della Rovere family, who owned the palazzo until the nineteenth century, although perhaps the owner should be named as Luigi Lante Montefeltro della Rovere, fifth duke of Bomarzo (r. 1771–1795), who was the presumed head of the household at the time the statue was in the courtyard. The Palazzo Lante still exists; it is located in the Campus Martius, near the Basilica di Sant’Eustachio and the Pantheon, at Piazza dei Caprettari 70 (fig. 1, location E).[24] When the statue was illustrated in the eighteenth century, it was completed with arms and legs attached to a supporting tree stump; a crescent moon was added to Aphrodite’s head, creating a pastiche of ancient and modern parts. It is not clear how the statue came to be at the Palazzo Lante nor when it left the collection, though a statue of Diana in the courtyard of the palazzo is mentioned in travel literature into the early 1800s.[25]

Comte James Alexandre de Pourtalès-Gorgier, Paris, by 1841, [mode of acquisition unknown]; sale, Catalogue des objets d’art qui composent les Collections de feu M. le Comte de Pourtalès-Gorgier, Paris, 21 March 1865, p. 16, lot 56.

![The condition of the Diana statue, acc. no. 23.82, when it was in the Pourtalès collection from Charles de Clarac, Musée de sculpture antique et moderne IV (Paris: Imprimerie royale, 1826? [reprint 1850]), pl. 577; no. 1243](https://journal.thewalters.org/wp-content/uploads/Fig.-6-b29325997_0011_0058.jpg)

The condition of the Diana statue, acc. no. 23.82, when it was in the Pourtalès collection from Charles de Clarac, Musée de sculpture antique et moderne IV (Paris: Imprimerie royale, 1826? [reprint 1850]), pl. 577; no. 1243

An 1841 catalogue of the collection of James-Alexandre de Pourtalès (1776–1855), comte de Pourtalès-Gorgier, in Paris includes a statue of Diana the huntress that was previously in the “palais Lanti” or the Palazzo Lante in Rome.[26] The statue would have been kept in Pourtalès’s mansion in the eighth arrondissement at 7 rue Tronchet in Paris, which is now a luxury hotel. A drawing published before 1841 confirmed that the Pourtalès Diana is the same statue as the one from the Palazzo Lante, while also showing that the previously attached arms and crescent moon had been removed by that time (fig. 6).[27] The statue was included in the March 1865 sale of the Pourtalès collection as lot 56.[28] There is currently no indication of who purchased the statue at the sale.[29]

Henri Daguerre, Paris, by 1921, [mode of acquisition unknown]; Joseph Brummer, Paris and New York, 1921, by purchase [Brummer inv. no. P220]; Henry Walters, Baltimore, 1922, by purchase; Walters Art Museum, 1931, by bequest.

The statue when it was unpacked in 1932; this is the current condition of the statue. Unidentified Roman sculptors, Torso of Artemis with Head of Aphrodite, Italy, 1st century CE, marble, 51 9/16 × 20 1/16 × 14 9/16 in. (131 × 51 × 37 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, acquired by Henry Walters, 1922, acc. no. 23.82

In 1921, fifty-six years after the Pourtalès sale, Joseph Brummer purchased the statue from Henri Daguerre in Paris. We do not yet know from whom Daguerre acquired the statue or in what year. Unlike other items sold by Brummer, there is no picture or drawing of the statue, to which he assigned the number P220, on his inventory card, only the description that it is an antique statue in marble representing Diana with restorations.[30] Brummer shipped the statue from his Paris gallery on Boulevard Raspail to his New York gallery on E 57th Street. The inventory card records that it arrived in New York on 30 December 1921 and was purchased there by Henry Walters on 24 May 1922. According to the “Anderson Journal,” a log book recording items received at the gallery in Baltimore,[31] the statue and its base arrived at the Walters gallery in two separate crates in December 1922. The crates were not opened until a decade later (and several months after Henry Walters’s death) on 8 and 9 April 1932, when the shipment containing the statue was recorded and photographed as M-171 as part of the inventory of Henry Walters’s estate (fig. 7).[32] The statue is now on view in the Ancient World lobby at the Walters. We do not know when the restored legs were removed, but it seems to have happened prior to its arrival in Baltimore, as the archival image from when it was unpacked in 1932 shows it essentially as it is now. An undated note in the object file suggested that the head ought to be separated from the body, as was done with other sculptures that were determined to be pastiches made up of elements from different ancient sculptures.[33] It is fortunate that this never happened, as the incorrect pairing of multiple goddesses created a unique work of art whose movements have been much easier to trace over more than 240 years. The increasing availability of rare books and archival records, particularly online but also in physical libraries and archives that must be accessed in person, have been key to understanding the movements of this statue.

Sarcophagus for an Infant with Two Cupids Holding a Shield, acc. no. 23.162

This small sarcophagus, likely for an infant or toddler, depicts two flying cupids, or erotes, holding a round shield. Two panthers crouch below the outstretched arms of the cupids. Carved at one end is the representation of overlapping shields and spears, which was probably added in the nineteenth century. The lid is missing. In the interior there is a raised semicircular area on one side, presumably indicating where the head of the deceased was placed. No traces of letters have been detected on the shield, although that is the place where the name and age of the deceased would most likely have been recorded. Comparison of the size of this sarcophagus with others where the age of the deceased is noted indicates this sarcophagus may have been for an infant or toddler between five months and two years old.[34]

Provenance

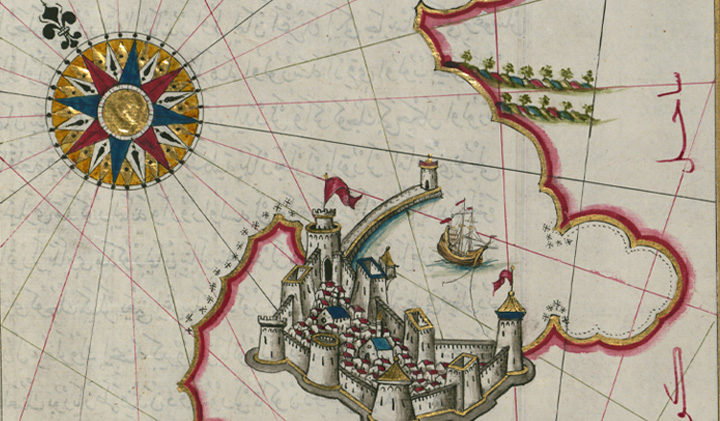

Clemente Maraini, Rome, by 1885, by excavation [said to have been excavated from the so-called Licinian tomb, Rome, 1884]; sale, Pio Marinangeli and Massimiliano Pirani, Rome, by 1892. Don Marcello Massarenti, Rome, by 1894, by purchase [marble no. 8]; Henry Walters, Baltimore, 1902, by purchase; The Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, 1931, by bequest; Museum deaccession, 1991; Sale, Sotheby’s, New York, European Works of Art, Arms and Armour, Furniture and Tapestries, 13–15 January 1992, lot 381; Private collection, Maryland, 1992, by purchase; Sale, Christie’s, New York, Antiquities, 11 April 2022, lot 110; Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, 2022, by purchase.

Clemente Maraini, Rome, by 1885, by excavation [said to have been excavated from the so-called Licinian tomb, Rome, 1884]; sale, Pio Marinangeli and Massimiliano Pirani, Rome, by 1892.

One group of Roman marble sculpture acquired from Marcello Massarenti was highly celebrated and very well recorded prior to entering the Massarenti collection—a group of sarcophagi from the Licinian Tomb in Rome. During building construction in 1884–1885, three underground chambers were found near the Porta Salaria, Rome, on the grounds formerly belonging to the Villa Bonaparte on Via Piave (fig. 1, location F). Rodolfo Lanciani, an archaeologist in Rome who had access to everything excavated in the city during his long career (1878–1927), described the tomb as “the richest and most important of those [tombs] found in Rome in my lifetime.”[35] Inside the chambers were several inscribed altars, sarcophagi, and portraits, and other items, including one intact inhumation burial. According to the excavated inscriptions, the mausoleum belonged to the Licinii and Calpurnii families, which were prominent from the late Republic well into the Imperial period (mid-first century BCE–early third century CE).[36] The tomb was never fully documented, and the finds are currently dispersed: the altars and two sarcophagi are in the Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome; a group of portraits and one other sarcophagus is in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen; and eight sarcophagi, including the infant sarcophagus, are at the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

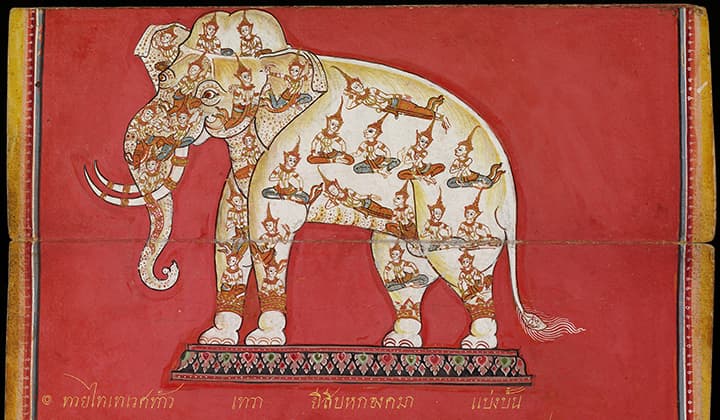

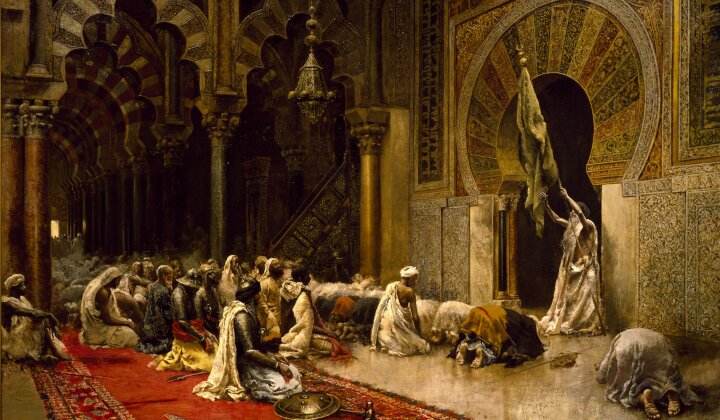

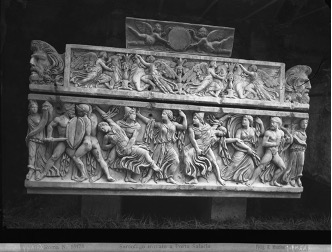

Pre-1892 image of the Sarcophagus for an Infant, now Walters Art Museum, acc. no. 23.162, on top of the Leucippidae sarcophagus, Walters Art Museum, acc. no. 23.32. Photo © Governorate of the Vatican City State—Directorate of the Vatican Museums

Unlike the altar of Marcus Iunius Rufus, there is not enough information about who originally purchased the sarcophagus in antiquity, so the provenance statement begins with the first known owner after the tomb was uncovered. Clemente Maraini (1838–1905), of Banca Italia, which owned the land where the tomb was found, was most often mentioned as the owner of the objects found in the tomb.[37] Information describing the place of discovery sometimes appears in a provenance statement because it is significant to the object’s history and because the data is easier to find on the collections website if entered like this. Epigraphist Enrico Stevenson mentioned that a small rough sarcophagus with geniuses, dated a little later than the first- to early second-century CE altars, was found in the first chamber of the Licinian tomb.[38] An image in the Vatican archive dated prior to 1892 showing the infant sarcophagus with another Licinian-tomb sarcophagus at the Walters helps to confirm that the infant sarcophagus at the Walters is the one described by Stevenson (fig. 8), and that it was kept with the larger sarcophagi. The sarcophagi are mentioned as a group in various English language publications as being on display in the gardens at the Palazzo Campanari, on the Via Nazionale, by 1885 (fig. 1, location G), where they could be seen with permission of Maraini, along with the altars, which he retained possession of until 1920.[39] Possibly by 1887, Maraini’s marbles from the tomb were put on display in or near the Palazzo Maraini, perhaps in the gardens, which some early publications located on the Via Agostino Depretis (fig. 1, H), while others noted it was at Via (Cesare) Balbo 1.[40] Lanciani reported that some of the tomb’s marbles (presumably, ten of the sarcophagi) had been moved to the gallery of art dealers Pio Marinangeli and Massimiliano Pirani, near the Spanish Steps at Via della Mercede in 1892 (fig. 1, I),[41] when Maraini, or one of his heirs (or perhaps a co-owner of the tomb objects),[42] decided to sell the sarcophagi, either through direct sale to Marinangeli and Pirani or by employing the dealers as agents to sell the sarcophagi on his or his potential co-owners’ behalf.

Don Marcello Massarenti, Rome, by 1894, by purchase [marble no. 8]; Henry Walters, Baltimore, 1902, by purchase; The Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, 1931, by bequest;

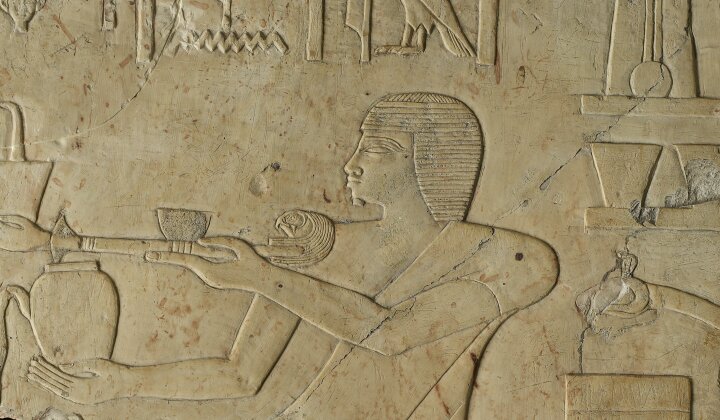

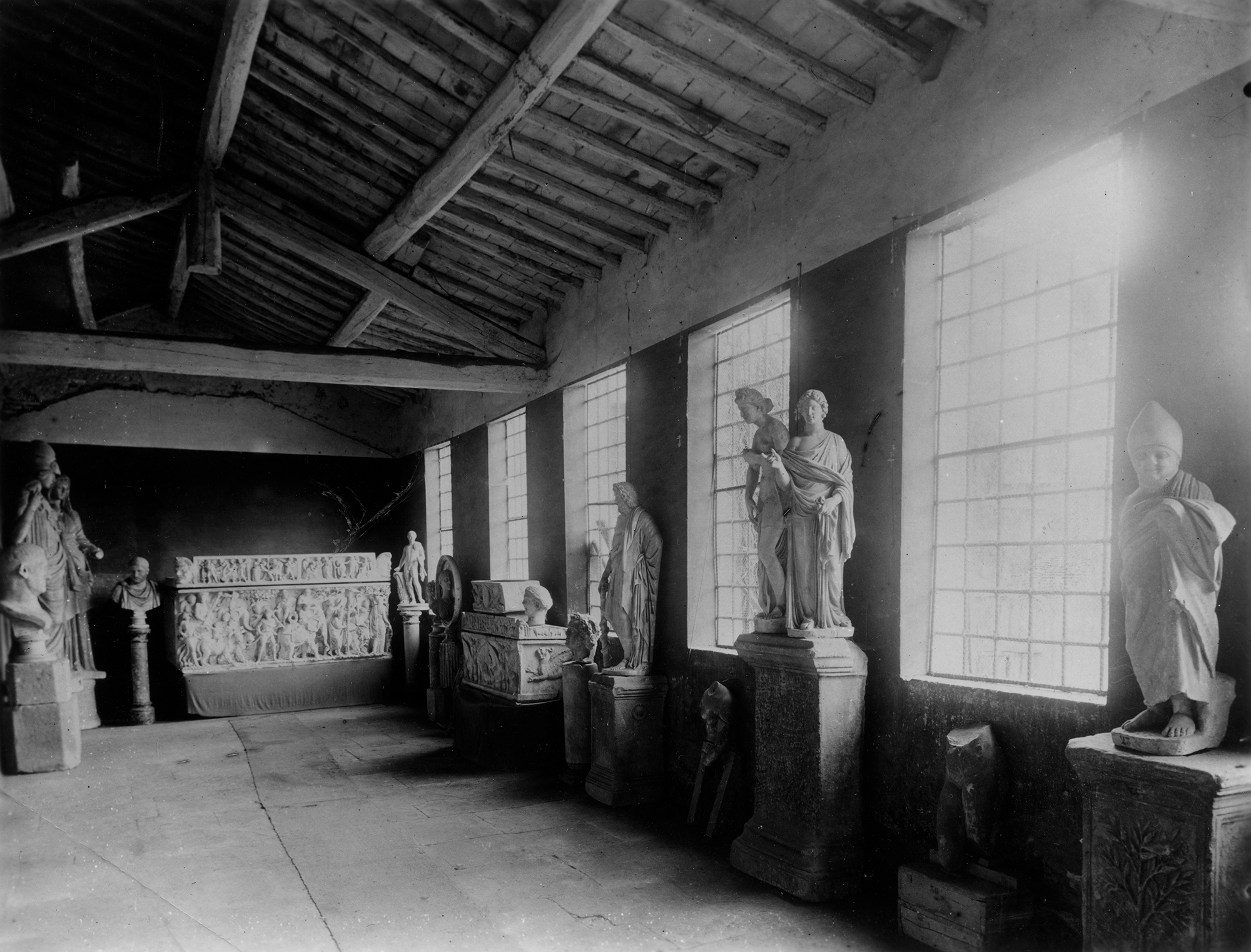

A ca. 1902 image of the marbles from the Massarenti collection as stored in the warehouse on the Via di Porta Angelica. The Sarcophagus for an Infant, acc. no. 23.162, is visible in this photo in front of the second window from left stacked on top of the Sarcophagus with Griffins, acc. no. 23.35

Marcello Massarenti purchased eight sarcophagi, including the infant sarcophagus, from the Licinian tomb group some time after 1892 but prior to 1894, when they were included in the English language publication of his collection.[43] As noted above, Massarenti stored the marbles from his collection at a warehouse (fig. 9) on the Via di Porta Angelica (fig. 1, D). Like the altar of Marcus Iunius Rufus, the infant sarcophagus once had the numeral “8” stenciled on the front, which was its Massarenti collection catalogue number, though it was removed at some unknown date. From 1894 to 1991, the provenance of this small sarcophagus is parallel to that of the altar of Marcus Iunius Rufus discussed above.

Museum deaccession, 1991; Sale, Sotheby’s, New York, European Works of Art, Arms and Armour, Furniture and Tapestries, 13–15 January 1992, lot 381; Private collection, Maryland, 1992, by purchase; Sale, Christie’s, New York, Antiquities, 11 April 2022, lot 110; Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, 2022, by purchase.

![View of the 2023 installation in the Roman galleries of the Sarcophagus for an Infant, acc. no. 23.162, with two other sarcophagi from the Licinian tomb, acc. nos. 23.36 and 23.37. Unidentified Roman sculptor, Sarcophagus for an Infant with Two Cupids Holding a Shield, Italy (Rome), marble, 10 13/16 × 33 11/16 × 13 5/16 in. (27.5 × 85.6 × 33.8 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, museum purchase [formerly part of the Walters collection], 2022, acc. no. 23.162](https://journal.thewalters.org/wp-content/uploads/RS451997_PS2_AncientWorld_DD_ED23_75_hpr-1.jpg)

View of the 2023 installation in the Roman galleries of the Sarcophagus for an Infant, acc. no. 23.162, with two other sarcophagi from the Licinian tomb, acc. nos. 23.36 and 23.37. Unidentified Roman sculptor, Sarcophagus for an Infant with Two Cupids Holding a Shield, Italy (Rome), marble, 10 13/16 × 33 11/16 × 13 5/16 in. (27.5 × 85.6 × 33.8 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, museum purchase [formerly part of the Walters collection], 2022, acc. no. 23.162

In 1991, the infant sarcophagus was one of fifty-seven Roman marble sculptures deaccessioned by the museum (then Walters Art Gallery) for sale at Sotheby’s New York, with the proceeds of the sale to benefit the acquisition fund for Ancient Art. Unlike most of the deaccessioned objects, which were sold in December 1991 in the Antiquities and Islamic Art sale, this sarcophagus was sold in January 1992 in the European Works of Art, Arms and Armour, Furniture and Tapestries sale as lot 381. Due to the lack of information in the Walters’ object file for this sarcophagus relating it to the other seven from the Licinian tomb, the relative speed at which the deaccession was processed, and the fact that Roman art was not a specialty of the curator at the time, the connection between this sarcophagus and the rest of the Licinian tomb group at the Walters was not recognized. This sarcophagus returned to the scholarly discussion of the Licinian tomb group, however, starting in 1997;[44] the first publication of photos of the infant sarcophagus from archives in Rome, and of the argument for its inclusion in the tomb group, occurred in 2003, at which point the location of the sarcophagus was acknowledged not to be known.[45] From 1992 to 2022, the infant sarcophagus was in an anonymous private collection in Maryland. It came up for auction at Christie’s New York in April 2022, at which sale the Walters Art Museum was able to buy it back. In early 2023, it was placed on view with the other seven sarcophagi from the Licinian tomb in the museum’s galleries of Roman art (fig. 10). The journey this object had, around some of the most fashionable and centrally located spaces of Rome, is notable, as is its later history of deaccession and reacquisition. These aspects of the object’s history tell a more interesting story than a provenance statement allows.

There is still more research that can be done on the provenances of these three objects, whether to fill in the gaps in documentation, to continue working to verify the moments noted here, or to extend their known ownership histories further back in time. The provenance statements that appear online for these three marbles in 2024 are dense with information but also are not quite able to convey their meandering journeys from Rome to Baltimore, which must be unpacked in longer narratives like this essay to clarify details. Although the publications and sketchbooks cited here include items that are centuries old, most of the information shared here was not known to the Walters Art Museum nor recorded in the curatorial files until I joined the Walters in 2017 and began working on the ancient Roman collection. We now know a great deal more than we did, yet there is still more to find out. It is a small triumph that the long histories of these three ancient marbles are now available, in short provenance statements and in longer form in this note, both of which are available online. Hopefully, this quick trek around Rome, Paris, New York, and Baltimore provides enough information to paint a fuller picture of the objects’ histories. More could be said about almost every detail given here: more about the owners, the locations the marbles were in, or even about the objects themselves. It is also hoped that this look into provenances of these three objects has given some idea of “how to read” a provenance statement (at least as provided by the Walters Art Museum), the kinds of information that such provenance statements pack into a very abbreviated text, and a few of the resources used in this type of research.[46] An object’s history is built up of many different components to make up what we think, for now, is its full story. But please do not be surprised if you check the provenance statements for these three pieces in a decade or two from the publication of this article to find that they have been expanded even further by new information that has come to light.

Acknowledgements

During my first few weeks at the Walters in 2017, I started to unravel the provenance of the Altar of Marcus Iunius Rufus, and I found an interested audience in Joaneath Spicer, who encouraged me to publish its illustrious history. I’m happy to have this note, which draws attention to the altar’s provenance, included in the volume of the Journal of the Walters Art Museum with essays in honor of her. My thanks go to Anna Clarkson, Librarian and Archivist at the Walters, for her help with archival resources, and to colleagues at the Walters who have contributed helpful suggestions, corrections, and assistance in preparing this for publication.

[1] Nancy Yeide, Konstantin Akinsha, and Amy Walsh, AAM Guide to Provenance Research (Washington, DC: American Association of Museums, 2001). Staff at the Walters are always working to update existing provenance statements, either to put them into the format we use, to correct the information, or to add new information. Note, although consistency is desired, the formats of provenance statements tend to vary by the style of the institution or even by the decisions of the individuals writing them.

[2] Intaglio Depicting Helios, second century CE, acc. no. 42.1157. Special thanks are due to Skylar Hurst, Robert and Nancy Hall intern in the Ancient Mediterranean Art department during summer 2019, who helped update the provenances of the Marlborough gems.

[3] See John Boardman, with Diana Scarisbrick, Claudia Wagner, and Erika Zwierlein-Diehl, The Marlborough Gems Formerly at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), esp. 1–12; 24–28; 83, no. 128 (this gem); and 205–209. Compare the provenance format of the Intaglio with Helios mentioned above, acc. no. 42.1157, with that of another Marlborough gem, acc. no. 2019.13.16, included in the J. Paul Getty Museum’s online collections: https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/109Q05.

[4] The “Rubens Vase,” ca. 400 CE, acc. no. 42.562. See Marvin Chauncey Ross, “The Rubens Vase: Its History and Date,” Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 6 (1943): 8–39.

[5] For a dynamic version of the map, with all the locations mentioned here plotted, please see Google Earth.

[6] The text with emendations and punctuation from EAGLE (Electronic Archive of Greek and Latin Epigraphy), record number EDR137198, reads:

[Si qu]a tamen pietas gelidos movet ṛụṣṭịc̣a M[anes],

rumpe moras: [spes haec s]ola est mihi gratia [vitae].

William Stenhouse, The Paper Museum of Cassiano dal Pozzo, A.7: Ancient Inscriptions (London: Harvey Miller, 2002), 123, no. 63, translates this section as: “But if ever rural devotion moves frozen fates, delay no longer: this hope is the one pleasure in life for me.”

[7] The Latin epitaph can be expanded as follows:

M(arco) Iunio M(arci) f(ilio) Pal(atina) Rufo

Soterichus paedagog(us) fecit,

hae sunt parvae tuae meaeq(ue) sedes,

haec certa est domus, haec colenda nobis,

haec est quem mihi suscitavi vivus

Stenhouse, Ancient Inscriptions, 123, no. 63, translates this section as: “To Marcus Iunius Rufus, son of Marcus, of the Palatina tribe. Soterichus, his teacher, made this. These are your and my poor resting-places; this is our sure home; this should be worshipped by us. This it is that I have erected for myself when alive.”

[8] The provenance statement for each of these three objects is current to the date of publication of this journal in 2024, but they may be updated in the future as more information is learned or as our provenance formats evolve. The statements have, in fact, been updated during the writing of this note.

[9] Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli, acc. no. MS.XIII.B.8, fol. 212r (p. 301). See Silvia Orlandi, Edizione Nazionale delle Opere di Pirro Ligorio, 8: Libro delle iscrizioni dei sepolcri antichi (Naples: De Luca, 2009), 281. Ligorio is known primarily as an architect and painter.

[10] Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, acc. no. N.A. 618, fol. 49r. See Giovanna Tedeschi Grisanti and Heikki Solin, “Dis Manibus, pili, epitaffi et altre cose antiche” in Giovannantonio Dosi: Il codice N.A. 618 della Biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze (Pisa: Edizione ETS, 2011), 328. Dosio was also an architect and sculptor.

[11] The British Museum, London, acc. no. 2005,0927.9. See Stenhouse, Ancient Inscriptions, 123, no. 63. This drawing seems to have been based on Ligorio’s.

[12] The Vatican Library, Vatican City, acc. no. Vat.lat.3439, fol. 127r.

[13] See the entry for Ligorio’s drawing at https://database.census.de/#/detail/63233. This record links to the other sketches through the entry for the altar itself at https://database.census.de/#/detail/160027.

[14] Ligorio wrote on the drawing that the altar was at S. Stefano, near S. Lucia della Chiavica (“a san stefano rincontro santa Lucia della chiavica”). The entry in Stenhouse, Ancient Inscriptions, 123, no. 63, identified the wrong location, placing the altar at the church of S. Stefano Rotondo on the Caelian hill, between the Colosseum and the Baths of Caracalla. The name of the neighboring church, S. Lucia della Chiavica, places it quite firmly, however, in the Campus Martius as described here.

[15] If the sixteenth-century location of the altar is at all near where it was placed in the second century, that might be important for theinterpretation of the altar itself but is too big of a topic to explore further in this note.

[16] Raphael Fabretti, Inscriptionum antiquarum quae in aedibus paternis asservantur explicatio et additamentum (Rome: Dominicus Antonius Hercules, 1699), 732, no. 452.

[17] Wilhelm Henzen et al., eds., CIL VI: Inscriptiones urbis Romae Latinae. Pars II: Monumenta columbariorum. Tituli officialium et artificium. Tituli sepulcrales reliqui (1882). This inscription is CIL VI, 9752. The entry in CIL provides, albeit in the Latin language and an extremely abbreviated format, the complete recorded history of the altar from Ligorio to its publication in CIL.

[18] The three altars, whose texts were also published in Fabretti’s Inscriptionum antiquarum, took different paths to the Villa Carpegna: acc. no. 23.16, a funerary altar for Marcus Ogulnius Iustus dated to the first century CE; acc. no. 23.17, a votive altar to Mithras for the health of the emperor Commodus dated to the second century CE; and acc. no. 23.184, a votive altar to Mother Earth (Terra Mater) dated to the first century CE. See, respectively, Fabretti, Inscriptionum antiquarum, 68, no. 37 (=CIL VI, 771); 689, no. 108 (=CIL VI, 727); and 694, no. 153 (=CIL VI, 23414).

[19] See Catalogue of Pictures, Marbles, Bronzes, Antiquities, etc. [in the] Palazzo Accoramboni [and Belonging to Marcello Massarenti] (Rome: Forzani and Co., 1894), 179, marble no. 15, where the altar was misinterpreted as a base for the pastiche statue made up of a portrait of the emperor Marcus Aurelius and a torso of an unidentified emperor, today separated into acc. nos. 23.80 and 23.215. See also the later publication, Catalogue du Musée de peinture, sculpture et archéologie au palais Accoramboni 2 (Rome: Imprimerie du Vatican, 1897), 143, marble no. 15,where the altar is no longer linked to the statue of Marcus Aurelius.

[20] Maria Saveria Ruga, “Da Roma a Baltimora: La collezione Massarenti,” in Andrea Bacchi and Giovanna Capitelli, eds., Capitale e crocevia: Il mercato dell’arte nella Roma sabauda (Bologna: Fondazione Federico Zeri, 2020), 117–45, at 120–21.

[21] This information is recorded in a letter from Henry Walters to William Laffan, dated 13 May 1902, preserved in the Walters Art Museum archives. Walters notes that he had secured the eighth floor of the Parker Building “at an exorbitant rental” with the intention of displaying “everything from Rome” along with 150 paintings he had in New York. He notes that the Tiepolo painting (acc. no. 37.657) and the marbles would not go in that space due to size and weight, and he would “have to find some place else for them.” The Parker Building at Fourth Avenue (now Park Street S) and E 19th Street was gutted by fire in early 1908, a few months after Walters moved the Massarenti collection to Baltimore. For additional information about the purchase of the Massarenti collection, see William R. Johnston, William and Henry Walters, the Reticent Collectors (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 153–69.

[22] Dominique Magnan, Le ville de Rome, ou description abregée de cette superbe ville (Rome, 1778), 3:46–47, pl. 27.

[23] Calcografia di Roma 3 (Rome: Giovanni Battista Canetti, 1779), pl. 20 and a brief note in the index, where the statue is listed after other statues of Diana.

[24] More research is needed to understand the art and antiquities collections at the Palazzo Lante in this period. Sometimes known as the Palazzo Medici Lante, its courtyard was renovated in 1760, which may be the point at which the statue was first placed on view. While more information would be needed to confirm that detail, it does give a point to start from in further research.

[25] See Ferdinando Mori, Sculture del Museo Capitolino (Rome: Pel Fulgoni, 1806), 1:132. One way to find out information about an object’s provenance is to trace the histories of objects that possibly came from the same collections. Two sculptures now in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin, were published in an 1891 catalogue of that collection, Beschreibung der antiken Skulpturen mit Ausschluss der pergamenischen Fundstücke, as having been in the Palazzo Lante: no. 138, an Eros, acquired by “Bunsen” in 1827, and no. 178, a Hera also acquired by “Bunsen,” this time from “Depoletti” in 1830. If there was a larger sale of collections from the Palazzo Lante by or before the 1820s that included these three statues and others, the movements of the Walters statue could perhaps be identified by following other statues from the palazzo.

[26] Jean-Joseph Dubois, Description des antiques faisant partie des collections de M. le Comte de Pourtalès-Gorgier (Paris: de Panckoucke, 1841), 14, no. 55.

[27] Charles de Clarac, Musée de sculpture antique et moderne IV (Paris: Imprimerie royale, 1826? [reprint 1850]), pl. 577; 55, no. 1243). A translation of the French text entry for the statue states, “This statue of Diana the Huntress, which is missing both arms from below the deltoid, comes from the Palazzo (“palais”) Lante and was restored by the sculptor Wolts.” No further information is currently known about the sculptor Wolts, but research on him ought to be another fruitful avenue for finding out more about this object’s history.

[28] Catalogue des objets d’art et de haute curiosité antiques, du moyen age et de la renaissance qui composent les collections de feu M. le comte de Pourtalès-Gorgier, sale, Paris, 6 February–21 March 1865, 16, no. 56. The sale was so large that it spanned several weeks, and this lot was sold in the seventh part of the sale on March 21. The digitized copy of the sale catalogue is hosted by Gallica, which is the Bibliothèque nationale de France’s digital library; resources such as this are instrumental for provenance research.

[29] Sometimes a sales catalogue with hand-written notes indicating the buyers for each lot is digitized and available online, but so far, no such annotated catalogue is known for this sale.

[30] Brummer started to describe the group as “Fragment of a statue” then crossed out “fragment” and changed it to “antique statue,” indicating that he was uncertain how to classify the pastiche he had. The Brummer Gallery Records, hosted online as part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Thomas J. Watson Library Digital Collections, are a marvelous resource for provenance research. Hundreds of artworks came to the Walters Art Museum from the Brummer Gallery.

[31] The Anderson Journal is named after James C. Anderson, who was the superintendent of Henry Walters’s Baltimore gallery and collections. The journal, in two volumes, covers the years 1908 to 1932. See Elissa O’Loughlin, “Our Mr. Anderson,” The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 70–71 (2012–2013): 137–42.

[32] Here “M” stands for “Marshall” after C. Morgan Marshall, who led the inventory of the collection in 1932 and served as Acting Director and then Administrator (essentially Director) of the gallery from 1934 to 1945. According to the estate inventory in the archives of the Walters Art Museum, there were 243 unopened crates of artwork, which included this statue, in the gallery when Henry Walters died.

[33] Such as the portrait of the emperor Marcus Aurelius and a torso of an emperor mentioned in note 19.

[34] See Janet Huskinson, Roman Children’s Sarcophagi: Their Decoration and Its Social Significance (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996).

[35] Rodolfo Lanciani, Pagan and Christian Rome (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1892), 277.

[36] For a discussion of the full contents of the tomb as well as the issues surrounding attribution of objects to a single mausoleum, see Katherine Bentz, “Rediscovering the Licinian Tomb,” Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 55–56 (1997–1998): 63–88; Frances van Keuren, et al., “Unpublished Documents Shed New Light on the Licinian Tomb, 1884-1885, Rome,” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 48 (2003): 53–139; and Patrick Kragelund, Mette Moltesen, and Jan Stubbe Østergaard, Licinian Tomb: Fact or Fiction? (Copenhagen: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, 2003). See also Barbara Borg, Roman Tombs and the Art of Commemoration: Contextual Approaches to Funerary Customs in the Second Century CE (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019) for a discussion of the family members that may have been buried in the tomb from the first to third centuries CE.

[37] Clemente’s relative Enrico also acted as a representative of the Banca Italia and appears in official documents to be acting in an ownership role with regard to the finds from the tomb. Other bank representatives, such as Ferdinando Campanari, seem to play a role as well, and there was some early dispute over the ownership; Clemente Maraini currently seems to be the correct person to call the “owner” of the tomb contents, but that may change as more information becomes available. See Van Keuren et al., “Unpublished Documents,” 80‒84 and passim; and Kragelund et al., Licinian Tomb, 17, 52, 63, and 116–17.

[38] Bullettino dell’Instituto, 1885, “Ulteriori scoperte epigrafiche nella Villa Bonaparte, sulla via Salaria,” 22–30, at 29: “…ed un rozzo sarcofago con genietti, di età assai più tarda.” Van Keuren et al., “Unpublished Documents,” 75–76, notes that “genietti” should be translated as cupids or erotes, because all the reports on the Licinian tomb use this term to refer to objects decorated with cupids or erotes. For discussions on the identification of this sarcophagus, see Bentz, Rediscovering the Licinian Tomb, 82, no. 8; Van Keuren et al., “Unpublished Documents,” 75–78 and 80; and Kragelund et al., Licinian Tomb, 55–57, 72, 74, and 111, no. 13, figs. 25 and 47.

[39] See, for example, Building News and Engineering Journal, 14 August 1885, 246; and John Henry Middleton, Ancient Rome in 1888 (Edinburgh: A. & C. Black, 1888), 507–509. Just north of the Palazzo Campanari are gardens that are likely the ones that housed marbles from the Licinian tomb immediately after their discovery.

[40] Lanciani, Pagan and Christian Rome, 280, says they were in the palazzo on Via Agostino Depretis; see also R. P. Pullen, “Recent Discoveries in Rome,” Journal of the British and American Society of Rome 1, no, 3 (1887): 96–100, at 98. An 1890 directory lists Clemente Maraini as living at Via Agostino Depretis 86, but accounts of a “Palazzo Maraini” seem to be limited to publications discussing the Licinian tomb marbles. Several sources indicate that Maraini’s marbles were kept at Via Cesare Balbo 1, but dates of these sources seem to indicate he lived there in the early twentieth century, after he sold the sarcophagi; see CIL VI, 31138, 31378, and 31721–27 (the entries for the altars from the Licinian tomb); Van Keuren et al., “Unpublished Documents,” 81n119; and Kragelund et al., Licinian Tomb, 65n47. While the current Via Agostino Depretis and the Via Cesare Balbo do intersect, it is not at either of those suggested addresses. The building that currently bears the address of Via Cesare Balbo 1 is not at that spot; it is at the intersection where the Via Cesare Balbo meets the Via Torino. Further research may clarify this detail.

[41] Lanciani, Pagan and Christian Rome, 280, gives the address where he last saw the marbles from the Licinian tomb as “No. 9 Via della Mercede” but many contemporary catalogues, now digitized and available online, indicate that Marinangeli and Pirani’s gallery was at “no. 11” in the Palazzo Gresham on that street. Please note that the correct family name of the second seller is “Pirani” as indicated by several late 19th-century gallery catalogues, and not “Sirani” as was published by Van Keuren et al., “Unpublished Documents,” 81n119; and Kragelund et al., Licinian Tomb, 63 and doc. 19. Additional sales catalogues from Marinangeli and Pirani may yield further information not only about the sarcophagi but also perhaps about other objects in the Massarenti collection.

[42] Kragelund et al., Licinian Tomb, 63 and 65n45, and doc. 46, 122–23. This publication believes the sarcophagi were sold to Marinangeli and Pirani, rather than consigned to them; see Kragelund et al., Licinian Tomb, 108.

[43] Catalogue of Pictures, Marbles, Bronzes, Antiquities, 178, marble no. 8; and Catalogue du musée de peinture, sculpture et archéologie 2, 141, marble no. 8. Although Ludwig Pollak noted that Massarenti had ten sarcophagi from the tomb, that seems to be in error; see Bentz, Rediscovering the Licinian Tomb, 73; and Kragelund et al., Licinian Tomb, 63. The summary of the sarcophagi in the 1894 catalogue of Massarenti’s collection states that while there were ten sarcophagi available for purchase, two “were purchased by the Italian Government, and placed in the Museum of the Termini in Rome, the other eight being bought by the proprietor of this Gallery;” see Catalogue of Pictures, Marbles, Bronzes, Antiquities, 171.

[44] Bentz, Rediscovering the Licinian Tomb, 82, no. 8.

[45] Van Keuren et al., “Unpublished Documents,” 75–78 and 80; and Kragelund et al., Licinian Tomb, 55–57, and 111, no. 13, figs. 25 and 47.

[46] It should be noted in particular how much these provenances rely on digitized manuscripts and early printed books; archival information is also key but can be harder to access if it is also not digitized.