Unidentified Peruvian artist, An Allegory of Saint Rose of Lima, ca. 1730–1760, Viceroyalty of Peru, oil on canvas, 64 × 50 9/16 in. (162.5 × 128.5 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, museum purchase, 2019, acc. no. 37.2940

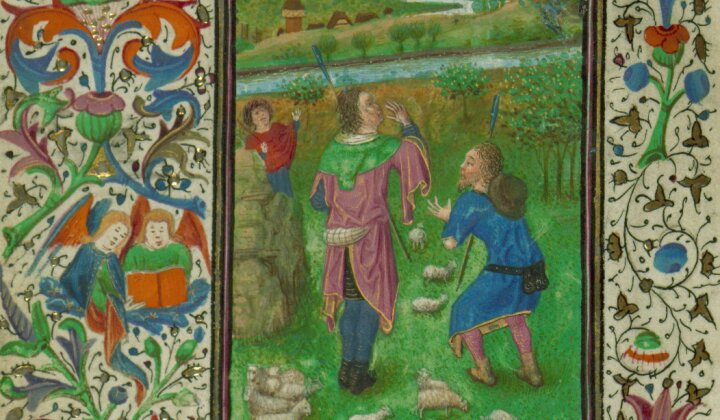

Seen from across the room, a large and colorful painting of a nun crowned with roses, her smile beatific, urges you to draw closer (fig. 1). While the top of the image seems quite in keeping with works of Western art in its illustration of a nun in a dark habit, contemplating a small image of the infant Christ, and surrounded by putti and clouds, the bottom half of the canvas is quite different. Here, it is revealed that the nun’s body emerges from an outsized rose, its huge stem grasped by a figure to the left in a blue tunic. Flanking this landscape on the other side of the rose is a dark-skinned man, wearing a tunic and headdress, whose raised hand suggests he is overcome with devotion to the figure above. The image is stylistically simple but similar to the Walters’ extensive collection of European painting, yet the lower register inspires curiosity as to the painting’s origin and purpose. Beautiful in its own right, the artwork is also illustrative of Latin American struggles for independence from Spain in the mid-eighteenth century. This essay discusses the artwork’s iconography and its historical context, making brief reference to materials and conservation research which has begun at the Walters, but which is still in progress and will be the subject of its own future publication.[1]

Hagiographies, or biographies that glorify their subjects, of female saints were immensely popular. This was true not just in the continent of Rose’s birth but also in Europe and beyond. Particularly since the late 1500s, St. Theresa of Ávila’s mystic revelations and transfiguration had ensured increased interest in female saints across the Catholic world.[6] Perhaps because of this interest, Rose’s beatification and canonization was a quick process. She was beatified by Pope Clement IX in 1667, just fifty years after her death, and canonized by Pope Clement X in 1671.[7] A number of publications told of her life and good deeds, including her association with roses, which were said to have fallen from the sky and perfumed the city of Lima at her death.[8]

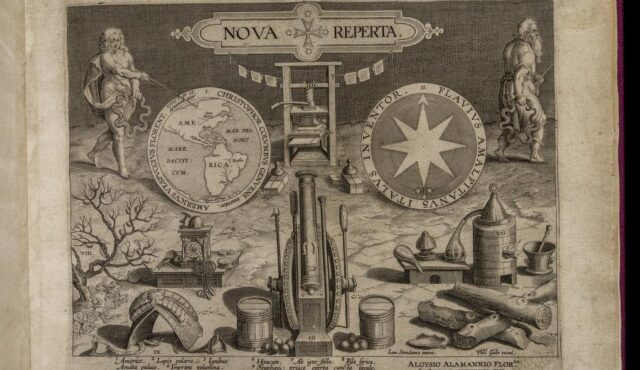

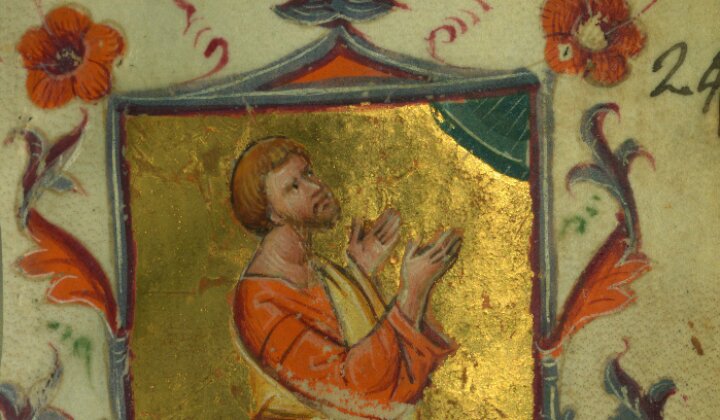

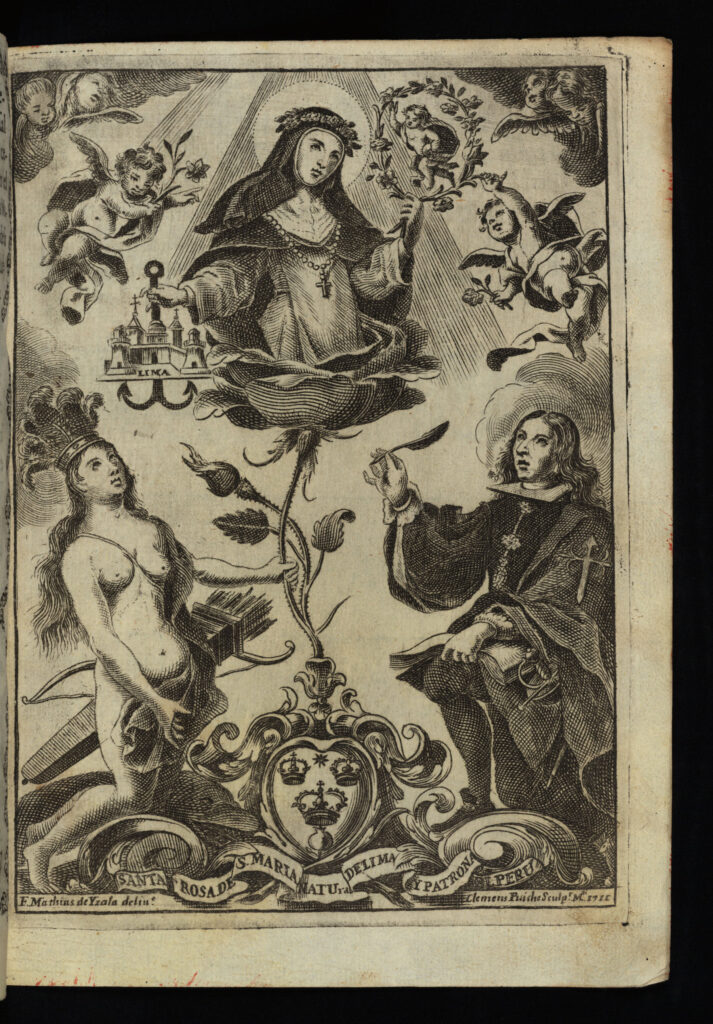

The painting, executed somewhere in the Spanish viceroyalty of Peru (encompassing all of modern-day Peru and Bolivia, as well as parts of other modern nations), shows Saint Rose of Lima (1586–1617). Born as Isabel Flores de Oliva in Lima, Peru, in 1586, Rose, or Rosa, as she later named herself, was the first person of American birth to be canonized by the Catholic Church. She became Patron saint (Patroness) of Latin America and of Peru in particular, and was the patron of embroiderers, florists, and gardeners.[2] As such, she was an immensely popular subject in the colonial Americas. However, like many colonial paintings of the time, rather than a specifically Andean view of the subject, this work draws quite directly on a printed work that had been produced in Europe and circulated in the Americas.[3] This was common practice during the era of the viceroyalty (1542–1824); in the contracts known for artworks produced in the Viceroyalty of Peru, many specify that the work should be completed “según estampas que se le de (according to prints given [the artist]).”[4] This painting in particular is based on an engraving that precedes the poems that comprise a collection of sonnets on Saint Rose’s life by the writer Luis Antonio de Oviedo y Herrera in a book published in Madrid in 1711 (fig. 2). While Oviedo y Herrera was born in Spain, he had been a soldier in the viceregal army, was knighted as the Count of Granja, and settled into retirement in Lima by the 1670s.[5]

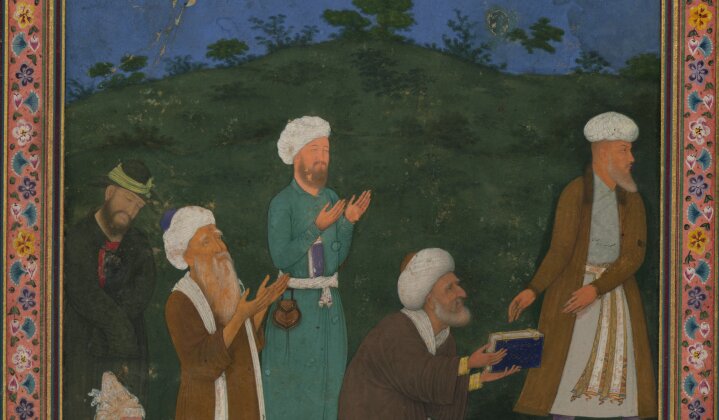

Clemens Puiche after F. Mathias de Yzala, Frontispiece to Luis Antonio de Oviedo y Herrera, Vida de Sta. Rose de Santa María, natural de Lima y patrona del Peru: poema heroyco (The life of St. Rose of Lima, native of Lima and patroness of Peru), Madrid, 1711, engraving, 5 3/4 × 8 1/2 × 8 in. (14.61 × 21.59 × 20.32 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, museum purchase, 2019, acc. no. 92.1350

These ideas of Saint Rose, immortalized by writings including this collection of sonnets by Oviedo y Herrera, have influenced that eighteenth-century painting we see today. The frontispiece to the poem includes an engraving. According to the text below, this was made from a primary drawing by the artist F. Mathias de Yzala, who worked with the engraver Clemens Puiche to create the print.[9] The engraving shows the saint as she emerges from her namesake rose, turning slightly to her left (the viewer’s right). Above her head, with one hand she holds or touches a halo of roses in which appears the Christ child. In her right hand she holds an anchor, with the cathedral of Lima balanced on its tines, and the word “Lima” written below. The anchor has been the symbol of Lima since at least the seventeenth century. It represents Lima’s role both as a port city and as the “anchor of the faith” after Catholicism was imposed upon Peru in the colonial period.[10] She is flanked below, as in the painting, by two figures. On the left is an allegorical figure of the continent of America, recognizable by her feathered headdress, bow, and quiver of arrows. At the right in the print is Oviedo y Herrera, with the decoration of the order of Santiago visible on his sleeve. The central rose sprouts from a shield at the bottom that contains three crowns and a star, the coat of arms of the city of Lima, which was known as the “City of Kings.” Below the crowns is a pomegranate, which, according to the art historians Dana Leibsohn and Barbara Mundy, links to Rose’s story in several ways, as “a symbol of the Catholic Church (the one fruit holding many seeds alluding to the Church’s universal embrace of the world’s peoples),” as well as a reference to Rose’s chastity, protected as the fruit is by a thick skin, and a reference to Rose’s penitential refusal to eat meat or indeed much food at all, subsisting reportedly on a diet of orange seeds and pomegranate flowers.[11] Below this shield is a banner with the words “SANTA ROSA DE S.[anta] MARIA, NATUra[l] DE LIMA Y PATRONA DEL PERU” which translates to “Saint Rose of Saint Mary, Native of Lima and Patroness of Peru.”

In the painting, several changes from the printed scene are evident. The figure of America is clad in a blue dress, not nude as in the print. Interestingly, a recent X-radiograph of the painting has shown that perhaps this allegorical figure was originally painted as nude, but clothes were added to the painting later.[12] While by the 1700s nudity was certainly acceptable for allegorical figures in Europe, in Latin America unclothed figures were rarely represented.[13] However, this character is still recognizable as an allegory of America because of the exuberantly feathered headdress she wears, feathers being a persistent symbol of the Americas from the earliest images transmitted from the continent.[14] At the bottom right, the writer Oviedo y Herrera has been replaced by the figure of a stylized Inca ruler. He kneels to Saint Rose, in a pose of deep reverence. He is recognizable to the casual viewer as a person of Indigenous descent, because of his darker skin tone and the tunic he wears, with square patterns, known as tocapu, at the waist; the allegorical figure of America also has tocapu at her dress’s midsection, albeit smaller. In the pre-Spanish era, these square patterns seem to have been specific and important for signaling ethnic, regional, or vocational identity, and they specifically may have been worn mostly by individuals of the highest ranks in Inca society. [15] In the colonial era, the use of tocapu expanded to their inclusion on wooden cups known as keros, and likely on other objects as well. By the eighteenth century when this painting was executed, the specific meaning of individual tocapus may have been only dimly remembered and understood by Indigenous and mixed-race populations. Alternatively it is possible that tocapu continued to be used in colonial times, but in a generalized form. However, the “confusion between Inca holdovers and Colonial interpretations actually serves to illustrate the persistent power of indigenous fiber traditions” in the Andes.[16] The motifs on his shoulders, resembling puma heads or epaulets, are likely Europeanizing additions, as these are not known from ancient Inca costumes. Similar decorations are painted in images of Inca nobility in a series of sixteen paintings dated to ca. 1680 showing the Corpus Christi celebrations in Cuzco.[17] While the Walters’ painting does not include the same level of contextual detail as works from this series, there is emphasis on the figure’s epaulets and wide bracelets, painted as though made of gold, reminding viewers of the importance of the Viceroyalty of Peru in controlling vast gold mines in the region. The ruler’s association with the Americas is reinforced by the feathered collar or necklace he wears. The cloak, or yacolla, which drapes over his left arm, was known to be worn by men of importance.[18]

Thus, to initiated viewers, the man would have been instantly recognizable as a member of the Inca royal family, likely the ruler himself, because of the depiction of the llautu, a colored band around the forehead, from which protrudes the mascaypacha, a red fringe, both of which were integral parts of the Inca crown.[19] However, by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the mascaypacha’s “meaning has expanded from signifying legitimate descent from the ruler to a more general claim of political authority.”[20] In the painting, this is complemented as well by another tocapu above the diadem, from which sprout three flowers. An eighteenth-century viewer would also have easily recognized these as the cantuta, a flower associated with Inca nobility since pre-Columbian times, which is still the national flower of Bolivia and Peru and used in modern-day funeral ceremonies. By the mid-eighteenth century, when this work was painted, kuracas, or Indigenous nobles, still enjoyed some privileges in the Spanish colonial system, but the majority of Indigenous peoples were employed in forced labor and mired in poverty.[21] Beginning in the late seventeenth but especially in the eighteenth century, various Indigenous nobles began to struggle against colonial rule in legal and symbolic ways. When those proved unsuccessful, these protests culminated in several episodes of armed rebellion, most notably a major uprising by José Gabriel Condorcanqui Noguera (better known as Túpac Amaru II) in 1781 that ended in the deaths of the rebel and almost his entire family, and punitive massacres of an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 Indigenous people across the Viceroyalty of Peru.[22]

The scholar Luis Wuffarden, who in 2016 examined photos of the painting to write a detailed description of it for the dealer who had it, notes that the increasingly frequent deployment of images of Inca royalty in paintings of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was not casual. The images were commissioned and consumed not only by Indigenous peoples but also by criollos, or people of Spanish descent born in the Americas, who, although of European heritage, were generally barred from occupying the highest levels of colonial bureaucracy. Because of this, through the creation and exhibition of such images they “sought to exalt the place of their origin, evoking the ancient Inca monarchy, which gave a unique status to the “kingdom of Peru” and situated it at a level of equality in relation to other kingdoms integrated into the universal Spanish monarchy. These elements confer on the work an extraordinary iconographic value, since this type of representation would be massively exiled and destroyed after the defeat of the great rebellion of Túpac Amaru II in 1781.”[23]

In fact, the earliest known extant painting of Túpac Amaru II, dating to the period 1784–1806, was recently discovered, in 2015, among a trove of watercolor paintings in Argentina.[24] In it, the leader, mounted on horseback, wears a crown including three cantuta, a symbol of leadership not unlike the one worn by the ruler in the Walters’ painting. Small wonder, then, that in the wake of the uprising, Inca-style dress was prohibited in Peru. Colonial authorities were concerned that “the use of national garments could bring to their minds, the ancient Incaic memories…,”[25] that is, reminders of a time before the Spanish invasion and its concurrent epidemics and siphoning of natural resources and labor from the Americas. Not only the actual garments, but images that showed them—paintings similar to the Walters’ of Rose of Lima—were banned and ordered to be destroyed.[26] How the Walters’ image survived is unknown, but its size (just over 4 × 5 feet) makes it likely an object of private devotion, for example, for use in a personal chapel. It is possible that an owner, particularly if they were not close to the centers of colonial power, might have chosen to conserve and hide the work rather than actually destroy it.[27]

Historical Background of the Cuzco School

The painting was likely created by one of the painters of the Cuzco school of painting. Rather than an actual academy, this was a circle of artists founded by Italian painters who emigrated to Peru and were settled in the Andean region of Cuzco starting in 1574.[28] While Cuzco was the headquarters of religious orders such as the Dominicans and Franciscans in the Viceroyalty of Peru, it was also the former capital of the Inca empire and a stronghold of Indigenous power in the Andes. The Cuzco school endured between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, but its members began to focus more closely on Indigenous themes, tastes, and imagery after the success of its stars, Basilio de Santa Cruz Pumacallao (active 1661–1698) and Diego Quispe Tito (1611–1681), both members of Indigenous aristocratic families.[29] The Cuzco school was so popular that its painters and imagery spread widely throughout South America with local schools. Later painters of Peru are sometimes casually described as of the Cuzco school even when they trained and worked in other cities such as Lima or Arequipa, or even further afield. The Potosí school, for example, centered in today’s Bolivia, developed as a result of the wealth created by the region’s numerous mines. However, painters from as far afield as Argentina, Chile, and Ecuador could also be defined broadly as part of the Cuzco school.[30] The imagery of Saint Rose was immensely popular across South America, and to a lesser degree, Central America and Mexico. Her popularity in Argentina makes it possible that this could have been painted in Argentina, or exported there, in the mid-eighteenth century, although it is more likely to have been painted somewhere in today’s Peru.[31]

More information could have originally been available in the work itself, if there were writing on the central shield or medallion shown in the painting, perhaps to indicate a patron and/or artist. Unfortunately, only the top of this portion of the painting is present. After close inspection, paintings conservators at the Walters suggest the possibility that the painting was cut down on all sides of the canvas, perhaps at different times.[32] However, the bottom of the canvas seems to be most affected.[33] This type of cutting occurs at times to remove damaged parts of a canvas, whether it was subjected to mold, fire, or splashed liquids, or when the painting is moved to a new spot and its size might need to be altered to fit its surroundings.[34]

We can only speculate on the identity of the painter of the Walters’ Saint Rose. Certainly it is tempting to see an Indigenous or mixed-race artist who wanted to celebrate the glories of his native land and history, the “Incaic memories” of his family.[35] However, given that the well-developed iconography of an Inca ruler, contrasted with the idealized beauty of the saint, was a popular subject in the period 1730–1760, this could have been executed by a criollo (creole) or a European artist as well.[36]

Overall, much research remains to be done on this painting. A detailed analysis of the pigments employed, and closer analysis of the canvas (even the patches used) could help us date the work more precisely. As the first work from the colonial Americas to be purchased by the museum, An Allegory of Saint Rose of Lima helps contemporary visitors make connections between works of the ancient Americas that will be on view and works of Renaissance and Baroque European painting that have long been a draw for visitors to the Walters. Rose of Lima offers the museum a chance to expand the timeline of Latin American art on view and allows viewers an exciting glimpse of how seemingly purely religious works can also relate directly to specific political events of their time.

Acknowledgments:

At the Walters, Joaneath Spicer has in recent years played the role of an “elder stateswoman” for incoming curators—of the curatorial team of ten people, including the Senior Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs, seven have joined the museum since 2017. Joaneath has offered edits, opinions, and wise counsel on many occasions. She also sends along notices of artworks for sale that she feels may be of interest to me. In 2019, she sent along a digital dealer’s catalogue, noting that a painting of Saint Rose of Lima might be one of those. She was right. I am grateful to her for her encouragement and for the stimulating discussions we have had over the years. I am also grateful to Lisa Anderson-Zhu for the encouragement and help given to me for this article.

[1] Walters’ conservation staff consisting of Daniela González-Pruitt, Paintings Intern, and Pamela Betts, Senior Conservator of Paintings, are working in conjunction with Annette Ortiz Miranda, Conservation Scientist, to investigate the materials and processes of the painting.

[2] See https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Rose-of-Lima. On the Viceroyalty of Peru’s changing borders, see https://smarthistory.org/viceroyalty-peru/.

[3] Carolyn Dean was one of the first to extensively discuss this common practice in her 1996 article “Copied Carts: Spanish Prints and Colonial Peruvian Paintings,” The Art Bulletin 78, no. 1 (1996): 98–110. In recent years, scholars have worked diligently to identify prints that were the source of many colonial paintings, see PESSCA: Project on the Engraved Sources of Spanish Colonial Art, https://colonialart.org/front_page.

[4] Dean, “Copied Carts,” 98.

[5] For a brief biography of the author, see Fernando Rodríguez de la Torre, “Oviedo y Herrera y Rueda [o ‘y Ordóñez], Luis Antonio de,” in Diccionario biográfico español. Real Academia de la Historia, https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/7664/luis-antonio-oviedo-y-herrera.

[6] See “Feminine Genius, Holiness and St. Teresa of Avila,” Catholic Online, https://www.catholic.org/news/saints/story.php?id=57289.

[7] For more details of the life and canonization of Rose, see the entry for “St. Rose of Lima” at Catholic Encyclopedia online, https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13192c.htm.

[8] Rev. Frederick W. Faber, D.D., ed., The Life of Saint Rose of Lima (Philadelphia: Peter F. Cunningham & Son, Catholic Booksellers, 1855), 212, describes the scent of roses that permeated Lima. Other versions also discuss roses falling from the sky.

[9] The text reads “F. Mathias de Yzala, delin. Clemens Puiche sculp.” I have not found additional references to de Yzala as an artist, but Clemens Puiche, also known as Clemente Puche, worked as an engraver on many books. See Juan Carrete Parrondo, Diccionario de grabadores y litógrafos que trabajaron en España, Siglos XV a XIX, 267.

[10] Dana Leibsohn and Barbara E. Mundy, “Life of Saint Rose, Rose of Lima,” in Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520–1820, https://vistasgallery.ace.fordham.edu/items/show/1770.

[11] Leibsohn and Mundy, “Life of Saint Rose, Rose of Lima.”

[12] Research is ongoing to determine when the clothing was added. This section of the painting was damaged, and reconstructing its history is a complex task.

[13] It is notable that in the first printing of the poem in the Americas, a 1729 edition printed in Mexico City, there is no comparable image of the author and an image of America. The major engraved image in the book is of the Virgin of the Rosary, shown on page 2, and many smaller images, some of angels, on later pages. The poem was not printed in Lima until 1867, several decades after independence from Spain.

[14] See Hugh Honour, The New Golden Land (New York: Pantheon Books, 1975), 13 and 34. See also Heidi King, ed., Peruvian Featherworks: Art of the Precolumbian Era (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012), which shows how generalized and how unlike actual Peruvian featherworks these headdresses are.

[15] For information on tocapu and their use, see Rebecca Stone-Miller, To Weave for the Sun: Ancient Andean Textiles in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 1994), 59, 179, and 182.

[16] Stone-Miller, To Weave for the Sun, 182.

[17] In a description of that painting, Gridley McKim-Smith cites art historian Teresa Gisbert in concluding that the shoulder decorations were a colonial pictorial invention. See Teresa Gisbert, Iconografía y mitos indígenas en el arte (La Paz: Gisbert y Cia, 1980), 120‒24; and see also Gridley McKim-Smith, “Dressing Colonial, Dressing Diaspora,” in Joseph J. Rishel and Suzanne Stratton-Pruitt, eds., The Arts in Latin America, 1492–1820 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2006), 159. One of the paintings is included in Dana Leibsohn and Barbara E. Mundy, Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520‒1820 (2015), https://vistasgallery.ace.fordham.edu/items/show/1700.

[18] Elena Phipps, “Garments and Identity in the Colonial Andes,” in Elena Phipps, Johanna Hecht, and Cristina Esteras Martín, eds., The Colonial Andes: Tapestries and Silverwork, 1530–1830 (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), 16–41, at 20.

[19] On the use of the llautu and mascaypacha as markers of rulership, see Phipps, “Garments and Identity,” 28.

[20] McKim-Smith, “Dressing Colonial, Dressing Diaspora,” 159.

[21] John Rowe, “The Incas Under Spanish Colonial Institutions,” Hispanic American Historical Review 37, no. 2 (1957): 155–99, at 156–57.

[22] Rowe, “The Incas Under Spanish Colonial Institutions,” 158. On the aftermath of the rebellion, see Sergio Serulnikov, Revolution in the Andes: The Age of Túpac Amaru (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 120–44.

[23] Luis Eduardo Wuffarden, opinion about the painting provided by Robert Simon Fine Art, translation by Ellen Hoobler. Original (dated August 8, 2016): “…que buscaban exaltar su lugar de orígen evocando la antigua monarquía incaica que prestaba una personalidad única al ‘reino del Perú’ y lo situaba en pie de igualdad con relación a los demás reinos integrantes de la monarquía universal española.”

[24] See “Minuciosos documentos del Virreinato nunca antes vistos,” ámbito (1 December 2015), https://www.ambito.com/edicion-impresa/minuciosos-documentos-del-virreinato-nunca-antes-vistos-n3918031.

[25] Visitador dor José Antonio de Areche to King Charles III of Spain, 1781, as cited in Phipps, “Garments and Identity in the Colonial Andes,” 27.

[26] Serulnikov, Revolution in the Andes, 136.

[27] When wills have survived that concern art collections of viceregal subjects, including those of Indigenous descent, there are often surprising numbers of works owned and displayed in private houses. See Maya Stanfield-Mazzi, “The Possessor’s Agency: Private Art Collecting in the Colonial Andes,” Colonial Latin American Review 18, no. 3 (2009): 339–64, for some case studies.

[28] See Luis Eduardo Wuffarden, “The Presence of Italian Painting, 1575–1610,” in Luisa Elena Alcalá and Jonathan Brown, eds., Painting in Latin America, 1550–1820 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 257–74.

[29] Luis Eduardo Wuffarden, “The Rise and Triumph of the Regional Schools, 1675–1750,” in Alcalá and Brown, Painting in Latin America, 307–63, at 325–29.

[30] Wuffarden, “The Rise and Triumph of the Regional Schools.”

[31] Wuffarden, in his description of this work, feels that it “corresponds to a Cuzco-area workshop of the second third of the eighteenth century, an era of consolidation and expansion of the regional pictorial school,” translation by Ellen Hoobler. Original: “El estilo de la obra corresponde a un taller cuzqueño del segundo tercio del siglo XVIIII, época de la consolidación y expansión de la escuela pictórica regional.”

[32] As per former head paintings conservator Eric Gordon’s examination report of February 14, 2019, “Traces of what appears to be original paint have been found on all four tacking margins indicating that it may have been cut down from a larger composition.”

[33] González-Pruitt, working as a conservation fellow at the museum in 2023–2024, felt that the painting was largely or only cut down at the bottom, or possibly the top and bottom.

[34] According to Gordon’s report, “There are at least ten patches on the reverse which appear to be adhered with wax.”

[35] All known painters of the colonial Andes were men.

[36] The term criollo has a specific meaning in colonial Latin America, as a person who was born in the Americas, but descended fully from Spanish/European ancestry. These people often had less opportunities within the Viceroyal system than did peninsulares, or those born in the Iberian peninsula. See the entry on criollo at https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/criollo.