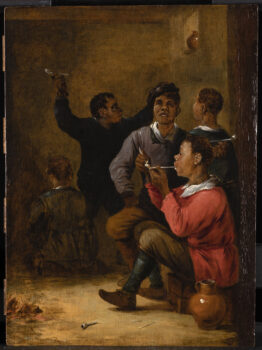

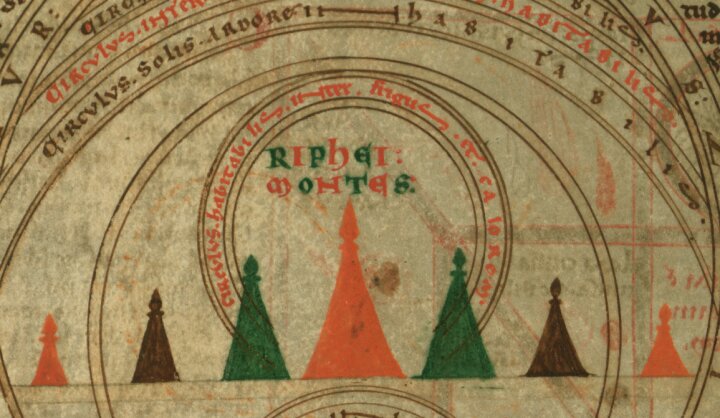

Unidentified Dutch artist, Black Youths Smoking in a Tavern, ca. 1630–1640, oil on panel, 35.7 x 26.2 x 0.5 cm. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, museum purchase, 2019, acc. no. 37.2941

A recent addition to the Walters Art Museum’s collection, Black Youths Smoking in a Tavern (fig. 1) is a small, unsigned oil painting on a wood panel depicting five figures in a dimly lit corner of a room. The figure on the far left is crouched on a low rectangular base facing toward the expanded area of the tavern. A young man in a dark jacket and matching trousers by the corner of the room appears to be conversing animatedly—lifting his arms and pipe into the air—while his companion in a green jacket appears to gaze and listen quietly. Of the two figures in the foreground, the man in a gray jacket and a soft cap holds a lit pipe and directly engages with the viewer. The artist depicts the exact moment when the foremost sitter in the red jacket lights his filled pipe and takes a test draw—suggested by his hollow cheek and pinched mouth.

This genre painting is thought to have been painted ca. 1630–1640 in Amsterdam: the simple and baggy garments of the figures—white linen shirts, jackets with small round buttons, wide breeches gathered below the knees, stockings, and shoes tied with ribbons—are associated with the seventeenth-century working class of that city. The panel’s small format as well as the intentional manner in which detailed figures in the foreground are juxtaposed with a comparably looser rendering of the background surroundings are reminiscent of other works by Northern European artists. While the Walters’ collection includes several Dutch genre scenes, this acquisition is believed to provide a rare glimpse into the social and communal life of working-class Africans in seventeenth-century Amsterdam.[1]

To corroborate the current stylistic attribution and interpretation of the painting, a comprehensive investigation of its materials and techniques was conducted through a collaboration with Dr. Glenn Gates, former Walters Conservation Scientist, and Dr. Joaneath Spicer, the James A. Murnaghan Curator of Renaissance and Baroque Art. This technical study, completed between 2021 and 2022 using an array of non-destructive instruments in the Walters Art Museum’s Department of Conservation, Collections, and Technical Research, also prompted the treatment of the painting, which was performed at the same time to reduce layers of disfiguring varnish and restoration that concealed many of the original features of the work.[2] This note characterizes the stratigraphy of the painting and addresses key findings revealed through the recent conservation efforts.

MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES

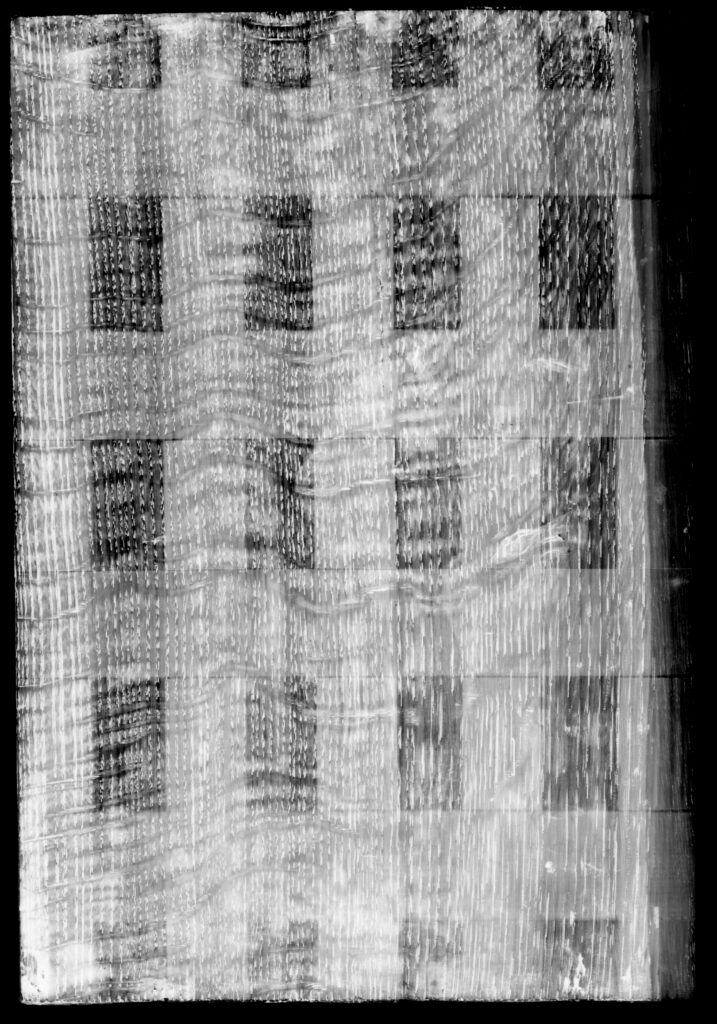

Medullary rays or flecking patterns visible as wavy lines in X-radiography of Black Youths Smoking in a Tavern (acc. no. 37.2941). The light and dark checkered pattern results from the modern cradle attachment on the verso.

The painting support of Black Youths Smoking in a Tavern is a single plank of hardwood with a dense vertical grain. It has been visually identified as oak, which was particularly favored by seventeenth-century Northern European artists.[3] The distinctive wavy pattern from the medullary rays noted on the verso and in the X-radiograph (fig. 2) is characteristic of quarter-sawn panels, following the standard and preferred practice of radially cutting planks from a tree trunk.[4] Any possible signs of a panel maker’s quality mark or branding, which might have confirmed its preparation, would have been destroyed when the panel was thinned by planing wood down from the back for the attachment of a cradle in a treatment prior to the museum’s purchase.[5]

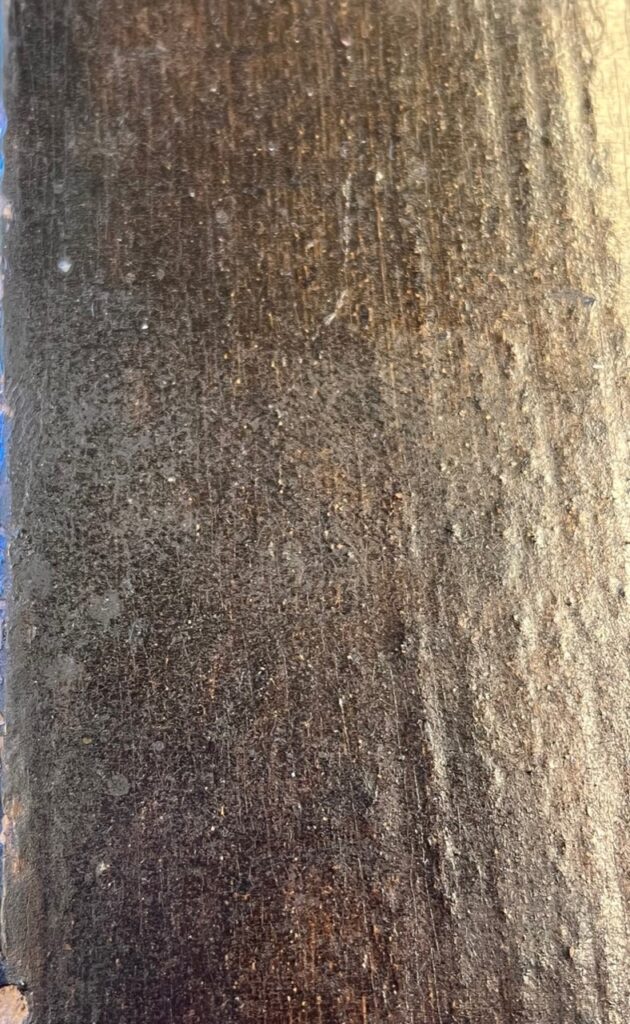

Detail of the pronounced panel grain, visible through the thin paint and ground layers of Black Youths Smoking in a Tavern (acc. no. 37.2941)

The panel painting surface was prepared with several layers of ground, followed by underdrawing and a translucent pigmented priming oil layer known as primuersel. Collectively these layers were thin enough to allow the vertical grain texture of the panel to remain visible (fig. 3). The ground is off-white in color and coarse in texture with large crystal-like particles readily visible at 50× magnification. A carbon-based underdrawing, carefully outlining the shape and details of the compositional elements, was detected on top of the ground using infrared photography (fig. 4).[6] This sketch is preserved under the pigmented primuersel, which functions as a warm toning base for the background in Black Youths Smoking in a Tavern. Elemental analysis of these layers confirmed the presence of calcium (from the ground) as well as lead, iron, and traces of manganese (from lead white, ochres, and umber in the primuersel).[7] Traces of impurities including chromium, titanium, potassium, zinc, and copper are also distributed throughout the layer structure.

Detail of the carbon-based underdrawing visible in infrared photography of Black Youths Smoking in a Tavern (acc. no. 37.2941)

The paint is glaze-like with a high binder-to-pigment ratio; oil peaks in the infrared region (1100–2400 nm) were identified using Fiber Optics Reflectance Spectroscopy (FORS).[8] Visual examination (microscopy), FORS, and X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF)[9] confirmed the presence of pigments commonly used by and readily available to seventeenth-century artists: lead white, vermilion, red lake, earth pigments, green earth, ultramarine, umber, van dyke brown, and bone black (table 1).[10]

All aspects of the panel stratigraphy are characteristic of seventeenth-century Netherlandish practices and these findings complement Dr. Spicer’s art-historical research on the painting. Additional dendrochronological analysis and lead isotope dating could help verify the suggested date of production. Both of these techniques, however, are destructive and would require sizable samples.

RECENT CONSERVATION TREATMENT AND KEY FINDINGS

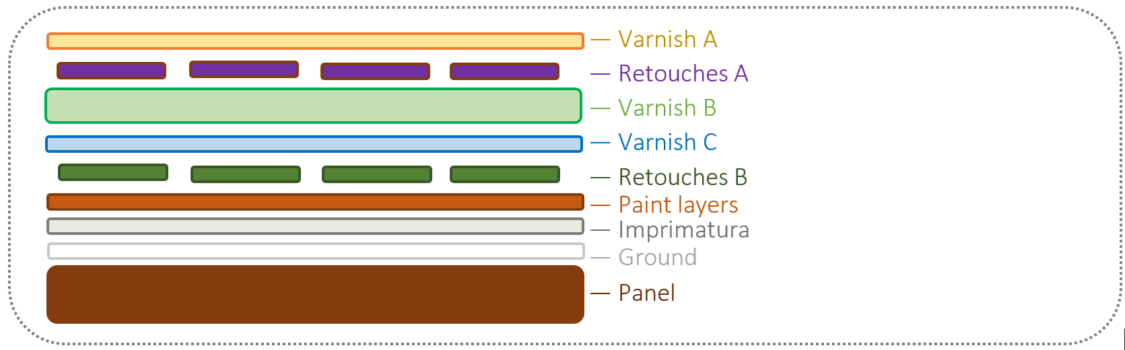

When Black Youths Smoking in a Tavern came into the Walters collection, it evidenced several campaigns of previous restoration. The panel had several vertical splits and an uneven extension that had been overfilled and heavily overpainted, all held in place by a cradle glued to the verso. Bright metal soap protrusions emerging through the paint, likely lead-based and coming from the primuersel layer, were present throughout the painting and had been concealed with overpaint.[11] Two separate campaigns of retouches had become opaque, discolored, and aesthetically disruptive over time; these retouches were interlaid between three layers of patchy, non-original varnish coatings (fig. 5a). These darkened varnish layers and retouches were reduced gradually in steps. Due to similarities in the solubilities of some of the retouches and metal soap protrusions, part of the older layer of overpaints was left undisrupted and disguised through scumbling, a technique in which a light layer of paint is applied over darker areas, allowing the deeper tones to shine through (fig. 5b). Losses were first isolated, filled with gesso, toned, and inpainted before a spray varnish was applied to evenly saturate the surface (fig. 5c).

Reducing the non-original materials revealed previously obscured details that enrich the painting, such as the frayed sleeve of the red jacket, different chamber designs for each of the three pipes, a single earring and the tendrils of smoke escaping from the figures’ lips (fig. 6a), as well as a flame over the packed pipe chamber (fig. 6b). Although the painting appears sketch-like at an initial glance, these minute details and the choice of materials used—the quality cut of the panel, multiple layers of thinly applied preparations, meticulous underdrawings that carefully outline the facial features and the composition, as well as the vibrant and strong colors—indicate how the artist deliberately planned every component of the work.

Figs. 6a and 6b

Details revealed after removing and reducing the thick varnishes and old retouches of Black Youths Smoking in a Tavern (acc. no. 37.2941). 6a: Earrings and a tendril of smoke; 6b: Flame lighting tobacco in the pipe bowl.

In early 2023, another version of this painting was acquired by the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, New Hampshire. While seemingly identical in composition and size, the Currier’s panel appears to have been painted directly over a thick, brush-applied white ground without a toning layer nor the fine details found in the Walters panel. Based on an initial review of images sent to Dr. Spicer, the paint handling in the two works also seems to indicate that they are by different hands. The Walters has not been able to directly compare the two versions of the painting. If the Walters panel is indeed a later copy,[12] the artist must have taken certain liberties in adding the expository attributes to better suit their interpretation of the scene and the group of young men. The variations between the two works and questions around the chronology of the paintings could provide a rich opportunity for future collaboration with the Currier Museum.

Table 1: A table of pigment identification through imaging and analytical techniques

| Imaging | Fiber optics reflectance spectroscopy (FORS) | XRF-ARTAX | Identification | |

| White | Lead white | Lead white | Lead (Pb) | Lead white |

| Red | Vermilion Red lake | Vermilion Red lake Red earth | Pb, Hg, Fe, <<Ca, K, Al | Vermilion Red lake Red earth |

| Yellow | Unclear | Unclear | Fe, Pb, Mn, Ca, K, P No Al, Si in highlights | Ochre + |

| Blue-black | Unclear | Unclear | Pb, Fe, Zn, Mn, Ca, K, Si, Al, P (with Hg impurity) | Ultramarine + Bone black mixture |

| Black | Unclear NOT carbon-based | Ca, Fe, Al, Si, P | Bone black | |

| Green | Unclear | Green earth verdigris | Fe, Si, Al, K, Ba, Ca, Zn, Pb; Cu not detected | Green earth + possibly a different, non-copper-based green pigment |

| Purple | Lead white mixture | Pb, Fe, Zn, Hg, Ca, K <Ti or Ba, Si, Al (Higher contribution from Fe, Al, and Si; less from Pb, Hg for blueish purple areas. Lower Hg and Pb, higher Fe, Zn, Ca, K, and P for shadows) | Lead white + Vermilion + Ultramarine + Bone black mixture | |

| Brown | Yellow ochre Umber | FeO Yellow ochre Fe, Mn, O Umber Fe, Mn, O Van Dyke Brown | Pb, Fe, Zn, Ca, K, Mn, Al, Si, P | Yellow ochre Umber Van Dyke Brown |

[1] Joaneath Spicer, “Afro-Amsterdammer Workmen Relaxing in an Inn: An Evocation of Community?” (Historians of Netherlandish Art Conference, Amsterdam, June 4, 2022).

[2] Treatment was supervised by Karen French, Head of Paintings Conservation.

[3] While a variety of hardwoods such as walnut, pearwood, cedarwood, Indian wood, and mahogany have been documented during the seventeenth century, “oak was the most common painting substrate in the Low Countries,” including Northern Germany and France. A seventeenth-century Dutch writer, Wilhelmus Beurs, also described oak as “the most useful wooden substrate on which to paint.” Dutch artists primarily used Baltic oak until 1650, while oaks from western Germany and the Netherlands were used after the breakdown of the Hansa trade due to the Second Swedish-Polish War. See Jørgen Wadum, “Historical Overview of Panel-Making Techniques in the Northern Countries,” in Kathleen Dardes and Andrea Rothe, eds., The Structural Conservation of Panel Paintings: Proceedings of a Symposium at the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles, CA: Getty Conservation Institute, 1998), 149‒77, at 150.

[4] Radial or quarter-sawing produces planks that are more dimensionally stable and resistant to distortion and moisture penetration. The presence of the flecking pattern, distinct from this sawing method, was considered to be a marker of good quality. See Wadum, “Historical Overview of Panel-Making Techniques,” 151.

[5] A cradle is a structural intervention consisting of a wooden grid glued to the reverse of a wood panel, with the intent to provide even restraint against warping, and possibly support behind splits. The cradle here consists of five fixed vertical slats in the grain direction, and four horizontal slats designed to slide under gaps in the fixed members to allow slight movement across the grain with changes in ambient conditions.

[6] Infrared reflectography of the painting was taken using a modified Nikon D90, Nikkor 18‒55mm lens, and 87A filter.

[7] The ground-underdrawing-primuersel system is well documented in seventeenth-century Dutch paintings. Recipes suggested applying ground consisting of weak glue and chalk, scraping the ground, planing the surface with a knife, then adding an oil layer composed of pigments such as umber, lead white, yellow ochre, red ochre, red lead, and carbon black. Northern artists initially sketched directly on top of the toning layers, much like their Italian counterparts. By the sixteenth century, the underdrawing was “sandwiched” between the ground and the toning layer. See Wadum, “Historical Overview of Panel-Making Techniques,” 167‒68.

[8] FORS spectra were acquired using FieldSpec 4 Hi-Res, recording the reflectance of the sampled area between 400 and 2400 nm. The spectra exhibited peaks associated with the hydroxyl groups at 1220 and 1440 nm, carbonyl and ester groups at 1932 and 2132 nm, and hydrocarbon/aliphatic groups at 1730 and 1750 nm.

[9] Elemental data were acquired with XRF-ARTAX at 50 kV, 500 μA, 1.0 mm, helium purge for better detection of lighter elements, 180 seconds.

[10] Seventeenth-century palettes typically consisted of white lead, yellow ochre, brown red (iron oxide), lake, yellow lake, green earth, umber, and bone or ivory black. Original text reads, “1. Le blanc de pomb, 2. L’ocre jaune, 3. Le brun rouge, 4. La lacque. 5. Le stil de grain. 6. La terre verte. 7. La terre d’ombre. 8. Le noir d’os ou d’ivoire.” See Roger de Piles, Les Élémens de Peinture Pratique, ed. Charles-Antoine Jombert (Amsterdam: Arkstée & Merkus, 1766), 99; and Sir Theodore Turquet de Mayerne, Pictoria, sculptoria et delle arti minori: 1620‒1646 (Anzio: De Rubeis, 1995), Folio 90.

[11] Metal soaps are damaging salts that may be produced by a chemical reaction between metal ions in certain pigments when mixed with fatty acids in an oil paint.

[12] The Currier Museum noted that their panel precedes Black Youths Smoking in a Tavern: “A later copy of the Currier Museum’s painting is now in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore; it was acquired in 2019 as a work by the Dutch artist Adriaen van Ostade as from the 1630s. . . . However, this work is derived from the Currier Museum’s painting, which was made in Antwerp, not Amsterdam.” See The Currier Museum of Art, “The Currier Museum Acquires One of the Earliest Paintings of Free Blacks Made in the West: The Museum Celebrates Black History Month with an Important New Acquisition,” 2023, https://currier.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/New-Acquisition-at-Currier-Museum-1.pdf.