In 2020, the Walters Art Museum committed itself to make accessible the histories of its origins. As a part of the institution’s Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion (DEAI) goals, the museum updated and expanded the biographies of its founders, William Thompson Walters (1819–1894) and Henry Walters (1848–1931), to publicly acknowledge their support of the Confederate cause.[1] My fellowship built on this research and considered the economic, political, and social networks of William and Henry Walters, connecting these histories to the institutional history of the museum. In other words, how did their businesses, politics, and social circles influence their identities as art collectors and how their collection developed over time? An important component of this work was examining the sources of their wealth, as well as their support and commemoration of the Confederacy.

Paul-Adolphe Rajon (French, 1842/3‒1888), William T. Walters, 1886, black crayon with white heightening on gray, moderately thick, moderately textured, cartridge-style laid paper, 12 × 9 5/16 in. (30.5 × 23.7 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Gift of Warren Delano IV, 1977, acc. no. 37.2544

William T. Walters’s American painting collection is embedded within these histories. Among the treasures of the museum’s nineteenth-century holdings is a small but impressive subset of American art. Some of these works are more recent acquisitions over the past two decades by artists like Joshua Johnson, Edmonia Lewis, Henry Ossawa Tanner, and Robert Seldon Duncanson. Others have longer ties to the Walters that date back to the earliest history of the museum in the nineteenth century. Patronizing Baltimore-based artists such as William Henry Rinehart and Alfred Jacob Miller, Walters also commissioned and acquired landscape paintings from Hudson River School artists including Asher Brown Durand, John Frederick Kensett, and Frederic Edwin Church. These works, some of which were part of the institution’s foundational collection bequeathed to the City of Baltimore by Henry Walters, were acquired by William T. Walters (fig. 1) between the late 1850s and early 1860s. As such, they are representative of William’s initial forays into the art market, at a moment when he was establishing himself both as a successful businessman and as a burgeoning art collector.

Yet a striking sense of absence characterizes the museum’s collection of American art. While abroad with his family in Europe during the Civil War, Walters liquidated a significant portion of the American art collection he had recently assembled. In 1864, he consigned 195 American and European works to fellow collector and art dealer Samuel Putnam Avery to sell over a two-day auction in New York City. The sale was a financial success for the two men, netting over $36,000 at the time, or nearly $720,000 today.[2]

A surviving catalogue from the auction offers some surprising insights into the development—or, rather, the regression—of Walters’s American art collection over time. Walters sold over fifty American paintings in 1864. Only nine paintings acquired by Walters before 1864 remain in the collection today, five of which are portraits that depict members of the Walters family and close friends. From his impressive collection of landscape paintings, he sold thirty at auction, opting to retain only three for his collection. In sum, Walters reduced his American painting collection to under one-sixth of its original size. Perhaps more telling is that he would add just nine American paintings (eight portraits and one still life) to his collection between 1864 and his death in 1894.[3]

Many questions surrounding the Walters Art Museum’s foundational American art collection remain. Why did Walters collect American art? What did he think about these artworks? And perhaps most intriguing, why did he choose to sell so many American paintings? This essay grapples with these questions and seeks to better understand William T. Walters’s relationship with the American art he collected. In doing so, it expands the scope of investigation beyond the artworks themselves to probe the larger context in which they were made, acquired, and displayed.[4] Looking to the brief period in which Walters collected and sold American art, between 1858 and 1866, this article explores the ways in which his businesses, social circles, and politics shaped his identity as a collector and influenced the evolution and devolution of his American art collection.

Walters’s collection of American art offers a particularly enticing opportunity to consider these histories. On the one hand, as a financial investment, it was a testament to his reputation as a prominent and successful businessman. On the other, its remarkable quality helped establish his place as a cultural leader in Baltimore and beyond. Yet it was also assembled at a moment in the nation’s history loaded with political uncertainty and conflict. Maryland’s position was especially tenuous during the Civil War years; geographically adjacent to Washington, DC, it was a border state, where enslaved individuals were held, but it was also deeply divided over issues relating to states’ rights and slavery.[5] One cannot posit Walters’s American art collection as separate from these larger economic, business, and political histories.

Engaging in this research is a messy business. It requires at once an investigation of the institutional history of the museum; a close study of the objects in its collections; a firm grasp of Walters’s social and business circles; and an understanding of broader artistic, economic, and political histories in nineteenth-century Baltimore and beyond. While my research is grounded in fact-based evidence and documentation, it is therefore also important to acknowledge gaps in the historical archive that limit our understanding of the convergences between Walters’s art, business, and politics. I have embraced the difficulties, limitations, and multiple possibilities that come about with this research, and at times use archival evidence to infer and interpret connections within his networks. Ultimately, it is when we put Walters’s American art collection back in its context to explore the many historical networks that influenced and were influenced by its creation that its full significance comes to light.

Buying and Collecting American Art in the Nineteenth Century

Collecting American art at mid-century aligned Walters with an impressive group of businessmen. As early as the 1830s, collectors such as the New York merchant Luman Reed and the Philadelphia publisher Edward Carey looked to American artists like Thomas Cole, Washington Irving, and Daniel Huntington for paintings to hang in their private collections. By the 1850s, railroad magnates John Taylor Johnston and Robert M. Olyphant, as well as the banker William Wilson Corcoran, had turned their attention to collecting American paintings, especially those that depicted the native landscape. Olyphant in particular was a staunch supporter of American art, and he collected it exclusively; by 1867, his collection numbered one hundred paintings, representing one of the largest collections of American art in the country at the time.[6]

A more local precedent for Walters was Robert Gilmor Jr., a merchant, shipowner, and East-India importer based in Baltimore. Gilmor began collecting art around 1790, amassing one of the most significant art collections in the United States prior to the Civil War. While his collection of over four hundred paintings consisted primarily of fourteenth-century Old Masters and seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish works, Gilmor also patronized nearly fifty artists actively working in America.[7] It is unknown if Walters ever met Gilmor, who died in 1848. However, there is evidence that he was aware of Gilmor’s collection, seeking out multiple works with Gilmor provenance for his own collection.[8]

At stake for many of these nineteenth-century collectors was not only a sense of personal achievement but also one of national accomplishment. Successful Americans were deeply mindful of the connections between their art collections and projects of cultural improvement that sought to celebrate the achievements of the United States on a national and international scale. For some, this resulted in the opening of their collections to the public for enjoyment and education. For others, like Corcoran, this responsibility had larger implications, leading to the development of an art collection for the nation to inspire patriotism and highlight the best examples of American art.[9]

As a prosperous businessman with an attraction to the arts, William T. Walters strategically joined in such efforts. Walters was born in Liverpool, Pennsylvania, in 1819, later moving to Philadelphia to study as a civil engineer at the University of Pennsylvania.[10] Though he worked in iron smelting for a few years, his interest in commerce led him to Baltimore. The city’s geographic position, paired with the recent completion of railroads that connected Baltimore to various towns in Pennsylvania, made it an attractive center for trade. By the time Walters arrived in Baltimore in 1841, rail lines linked the city to Wrightsville, Pennsylvania, enabling the transportation of goods to and from the Susquehanna River.[11]

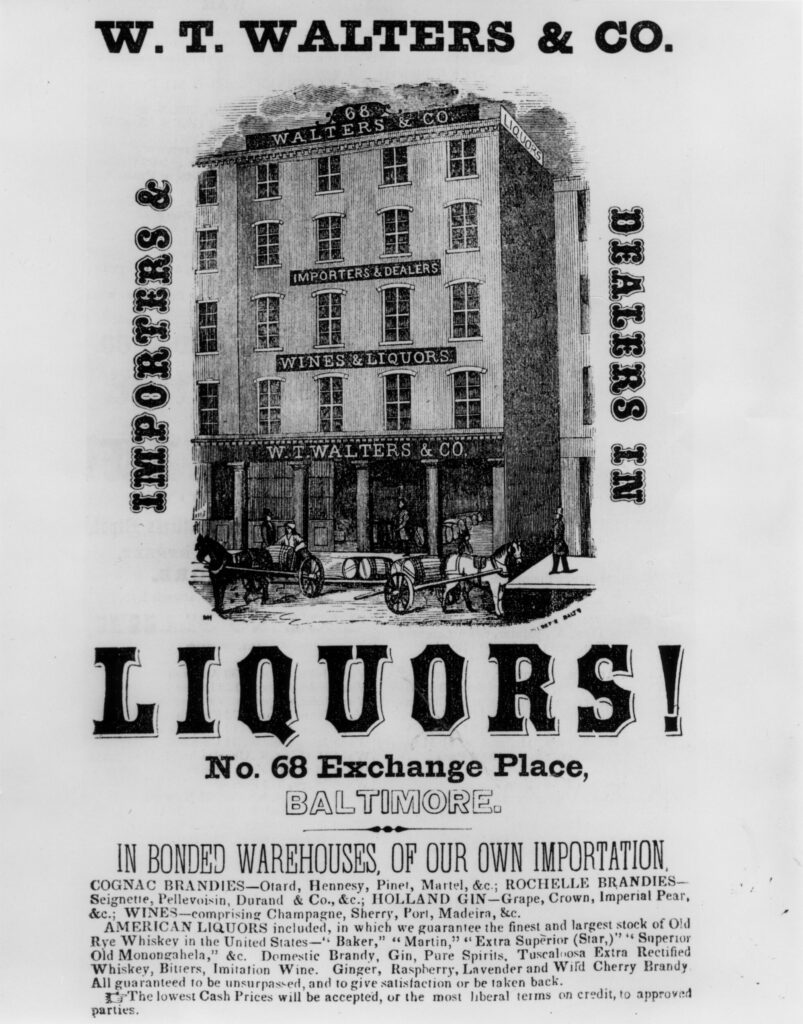

W. T. Walters & Company advertisement, page from the Baltimore City Directory, 1855‒56. The Walters Art Museum Archives, Baltimore

Such possibilities for trade, both through Baltimore’s rail lines and its harbor, likely contributed to Walters’s decision to become a merchant. In the early 1850s he opened William T. Walters & Company (fig. 2), a firm specializing in liquor that dealt in Pennsylvania rye whiskey, brandy, wine, and various other spirits.[12] At the same time, Walters expanded his business interests, investing in the Baltimore and Susquehanna Railroad Company (which was later consolidated as the Northern Central Railway Company) as well as steamship lines that would connect Baltimore south as far as Savannah.[13] Over time, Walters was characterized as a “distinguished citizen of Baltimore” and “a steadily successful merchant,” known for “his strong personal character as a merchant and a man.”[14]

Walters capitalized on his position in the world of business to engage in a series of purchases of local art. In 1857 he moved with his family to Mount Vernon Place, a developing neighborhood attracting wealthy merchants, railroad executives, and bankers, as well as cultural leaders like George Peabody, Enoch Pratt, and, later, Mary Elizabeth Garrett.[15] Perhaps inspired by their philanthropic efforts, Walters turned his attention to local artists to fill his new home. In the 1850s, he commissioned multiple works by the Baltimore-born artist and neoclassical sculptor William Henry Rinehart, in addition to sponsoring his travels abroad to Europe.[16] Walters also patronized Alfred Jacob Miller, a Baltimore artist best known for his depictions of the fur trade along the Green River Valley. After acquiring a few paintings from the artist in 1858, Walters commissioned Miller to produce two hundred watercolors inspired by his field sketches. A significant financial investment from Walters totaling $2,400, the watercolors were eventually bound into four albums.[17]

Asher Brown Durand (American, 1796‒1886), The Catskills, 1859, oil on canvas, 62 1/2 × 50 1/2 in. (158.8 × 128.3 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Commissioned by William T. Walters, 1858, acc. no. 37.122

Walters’s ambition to invest large amounts of money in his art collection extended to a national scale as well. In 1858, only a month before the Miller commission, Walters wrote to the celebrated Hudson River School landscape painters Asher Brown Durand and John Frederic Kensett to commission two works for his collection. Written just six days apart, the letters reveal Walters’s approach to leave the subject, size, and price of the artwork to the discretion of the artist. The tactic yielded impressive results; “the ‘Tide in Summer’ is splendid,” Walters wrote to Kensett, “I am delighted with it,” while conveying to Durand that his painting The Catskills (fig. 3) “seems to have rendered the subject of such universal congratulation that I assure you I feel very proud indeed.”[18]

Surviving correspondence exhibits the financial latitude with which Walters assembled his collection. While he originally offered each artist between $500 and $700 (with the final price to be set by the artist), he ultimately paid Durand $1,500—as much as three times the initial budget—for his painting. Regardless of the total cost, Walters cultivated close friendly relationships with both artists and would commission at least four additional paintings by Kensett and two more from Durand over the following years. None of these subsequent works remain in the Walters Art Museum’s collection.[19]

Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826‒1900), Morning in the Tropics, ca. 1858, oil on canvas, 8 1/4 × 14 in. (21 × 35.5 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by William T. Walters, 1858, acc. no. 37.147

While Walters worked to secure private commissions of Hudson River School landscapes, he acquired paintings at public auction as well. In December 1858, the National Academy of Design in New York City put on an exhibition and sale to benefit the widow and children of the American painter William Tylee Ranney. The catalogue produced for the sale lists 108 paintings by Ranney and another 104 paintings donated by well-known artists, including Durand and Kensett. As such, the auction was a veritable who’s who in art, attracting the most prominent artists and collectors of American art. Newspaper accounts of the sale reported that all lots “were disposed of—many of them at unexpectedly high prices.” Walters contributed to the auction’s success, purchasing over ten works and paying the highest amount for a single artwork, $535 for a small canvas by Frederic Edwin Church, titled Morning in the Tropics (fig. 4).[20]

In a letter to Kensett days after the sale, Walters revealed his motivations for the costly acquisition:

The Ranney sale indeed as you say has brought out some new features in regard to art—and it is very rare you know that the efforts of leading artists are exposed to popular competition and when those efforts chance to be “very good” or the “best” of the respective artist it is not to be wondered they reach a point above their medium productions—and it is this very feeling which impels me to think I should not only be wishing but desirous to pay for the best a better price.[21]

Quality, in other words, was nonnegotiable for Walters. Indeed, while he sought out many of the same artists as his fellow collectors, Walters established a reputation early on for the caliber of the works he acquired. Writing about Kensett’s landscapes, Walters described his attraction to a kind of felt realism in art; “there was a ‘realism,’ real, well defined actual water . . . no vagueness—no uncertainty . . . but I don’t think you ever have or can paint a picture without fine feeling,” he reasoned, “there is a poetry of art . . . and there is no art without it.”[22] That Walters admired Hudson River School paintings, which often faithfully recorded nature while appealing to higher spiritual and moral truths, therefore makes good sense.[23]

While finances certainly played a role in his collecting, Walters routinely prioritized the artistic quality and reputation of his collection over considerations of cost. He coveted paintings of the highest quality that visually advanced what he determined to be the best kind of art—art with a convincing realism, feeling, and poetry—believing that such works carried value well beyond monetary worth. Samuel Avery, who acted on behalf of Walters in many artist transactions, impressed a similar point upon the landscape painter Thomas Hiram Hotchkiss. In response to Hotchkiss’s desire to paint another picture for Walters, Avery explained that the collector “would I think at any time buy works of art if they were of any higher character than those he already has—you would be surprised to see the quality of his collection.”[24]

Samuel Valentine Hunt, after Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826‒1900), Morning in the Tropics, 1860, steel engraving, 5 1/16 × 9 1/16 in. (12.86 × 23.02 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired probably by William T. Walters, ca. 1860, acc. no. 93.169

Buying a painting like Church’s Morning in the Tropics at auction impressed this point upon Walters’s fellow collectors, too. The purchase was not only recorded in many newspapers at the time of sale, but also remembered years later; in December 1860, the leading art magazine The Crayon published an engraving of the painting by Samuel Valentine Hunt, describing it as “a picture sold at the sale of the Ranney collection, and which is now engraved as a souvenir of that event.”[25] One would imagine that Walters took delight in this added publicity, which further established his credibility and prowess as a collector. There are two copies of the engraving in the museum’s collection today, likely acquired by Walters to celebrate his triumph (fig. 5).

The Business Behind the Art

Walters’s successes in the art market had both direct and indirect connections to his business networks. His early correspondence with Durand and Kensett, for instance, was likely prompted by the 1858 artists’ expedition over the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (the B&O). In early June, a group of approximately fifty artists, poets, journalists, and businessmen boarded a train at the Camden Street Station in Baltimore bound for Wheeling, Virginia (fig. 6). Designed by the B&O as a publicity scheme, the five-day trip invited the group, which included leading Hudson River School artists such as Durand and Kensett, to document the natural scenery along the railroad.[26] The B&O likely did not extend an invitation to Walters, who was affiliated with its rival, the Northern Central Railway. He was able to capitalize on the trip, however, using the gathering in Baltimore as an opportunity to lay the groundwork for commissions from Durand and Kensett.

Group on cowcatcher of train, 1858, Artists’ Excursion Over the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Photograph Collection, Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture, PP262.36.

Concurrently, Walters may have had other business motives in connecting with both artists. Prior to formally commissioning a painting from Durand, Walters appears to have first met with John Durand, Asher’s son. John, who was a painter in his own right, was also involved in publishing. As an editor of the prominent art journal The Crayon, Durand was well connected with many artists, critics, and collectors, publishing stories and news that directly influenced the art market. Walters’s decision to seek out John may have therefore been a strategic one, enabling him to establish a relationship with the editor to encourage articles on topics like the Ranney sale a few years later.[27]

While Walters’s relationship with Asher and John Durand may have helped secure his standing as an art collector, his connections with Kensett went well beyond the realm of the fine arts. Indeed, it is probable that Walters leveraged his friendship with the artist to benefit his dealings in the railroad. As William Johnston has explained, correspondence between the two men was particularly amiable, ranging from insights into the New York art market to Kensett’s supply of Havana “segars,” which Walters stocked.[28] Kensett’s travels to Baltimore to visit his brother Thomas surely furthered his rapport with Walters. Following in his father’s footsteps, Thomas Kensett established a canning firm in Baltimore by 1851, capitalizing on the Chesapeake’s ample quantity of oysters. As Kensett & Co. grew, Thomas expanded his business interests, becoming a director of a steam ferry company as well as the Iowa River Railway.[29]

Though it is unclear if Thomas Kensett and Walters met in the 1850s, they did conduct business together in the railroad during the post–Civil War years. In December 1867, the two men became the biggest block owners of Wilmington and Weldon Railroad stock, effectively launching Walters’s career as a Southern railroad executive. Two years later, Kensett and Walters were elected to the board of the Wilmington, Columbia, and Augusta Railroad (which eventually consolidated with the Wilmington and Weldon). It is through these transactions that Walters was able to organize the Southern Railway project, a progenitor of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad. It is also how Walters, and later his son Henry, amassed a fortune that was used, in part, to acquire works of art.[30] Somewhat ironically, while Walters engaged in a successful business partnership with Thomas in the railroad, he sold all his landscape paintings by John Kensett. Correspondence between the collector and artist ceased after 1860, barring one letter from 1866, making it difficult to determine the nature of their friendship in later years.[31]

John W. McCoy was another figure that straddled Walters’s art and business worlds. Working in Baltimore as a journalist, McCoy took an interest in the city’s commercial and cultural development. In 1860, he joined Walters as an ally in the “railway war,” a period of great tension surrounding the creation of the Baltimore City passenger railway. McCoy traveled with Walters to Annapolis, with the intent to influence legislation surrounding the bill.[32] The two men united again after the Civil War, with McCoy joining W. T. Walters & Co. as a partner. While similarly minded in business, McCoy and Walters also shared a commitment to social and cultural causes; both were involved in the Baltimore Association for Improvement of the Condition of the Poor as well as the Allston Association, a Baltimore arts organization. Moreover, it is likely that, through Walters, McCoy met Rinehart, whom he would later champion through editorials and acquisitions.[33] In many instances, therefore, Walters used relationships in business and art reciprocally to further his standing in Baltimore.

Yet to fully understand the financial underpinnings of Walters’s businesses, one must look south. Indeed, many sources throughout the nineteenth century noted the collector’s connections to the Southern states; “Mr. Walters was a Southern man, doing very large business with the South,” one newspaper reported, while another declared that “he has done more to develop North Carolina than any other man,” referring to his work in the railroad.[34] Walters benefitted from Southern economies during his earliest years in Baltimore, and his connections—and especially those of his son, Henry—to such states only strengthened over time. In 1884, Henry moved from Baltimore to Wilmington, North Carolina, home of the headquarters of the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad. It was through his relocation that Henry met Pembroke and Sadie Jones, important socialites in Wilmington who would have a significant impact on all aspects of his life, including his marriage to Sadie in 1922 after Pembroke’s death.[35]

William T. Walters’s most direct connections to the South prior to the Civil War emerge within his liquor firm. Some of the products distributed by the company required additions of sugar and molasses during production, which were goods Walters secured from Louisiana.[36] It is very likely that Walters relied on his brother, Edwin, in such transactions. Fourteen years younger than William, Edwin Walters moved to Baltimore in 1848, working for the firm of Samuel Hurlbut, a commission merchant specializing in sugar. Edwin represented the Baltimore firm in Louisiana, establishing relationships with sugar planters to secure products for shipment. Through his work with Hurlbut, Edwin met Pinckney C. Bethell, a wealthy planter and businessman in the South who claimed ownership of enslaved individuals.[37] The two must have developed an exceptionally close relationship, as Edwin married Bethell’s niece, Virginia Torian, at Bethell’s home in 1860. Like Bethell, the Torians earned their fortune in sugar production, owning a plantation with enslaved workers.[38]

Having worked at least five years for Hurlbut in Louisiana, Edwin joined William T. Walters & Co. in 1857. There is documentation linking Walters’s firm to Hurlbut, Bethell, and the Torians well into the 1860s. For instance, when Bethell listed land for sale in a newspaper notice in 1865, both Hurlbut and Walters & Co. were listed as references. In 1869, Bethell assisted Edwin in purchasing a sugar plantation in Louisiana, located in the same parish where Bethell himself owned land. A few months later, the two men co-purchased the steamboat Dell, likely to facilitate the transportation of products along the Bayou Teche.[39] Other, more local connections existed between the families as well. Virginia’s parents, Thomas and Agnes Torian, both died relatively prematurely, leaving behind six young children. Some of the Torian children became wards of their maternal uncle, Bethell. The 1860 Census reports that at least three of the children—Sallie, Louise, and Agnes Torian—lived with Edwin and Virginia in their Baltimore home on Courtland Street. Surviving ledgers from Bethell reveal that he paid Edwin for this care, sometimes using Hurlbut as a conduit for the transactions.[40]

There is no evidence that William T. Walters personally knew Hurlbut, Bethell, or the Torian children under his brother’s care. However, one can safely infer that his business directly benefited from his brother’s relationships with these individuals and his dealings in the South.[41] William’s ability to produce liquor depended upon Southern economies that relied on enslaved labor, in areas that perpetuated the dynamics of the slave economy well after emancipation.[42] Walters thus profited from these economies, using his financial earnings from his liquor firm to commission and acquire works of art.

William T. Walters and the Confederate Cause

The finances undergirding Walters’s success as a businessman and art collector provide important context for his political leanings. Walters did not conceal his support of the Confederate cause, at least early on. At the outbreak of the Civil war in 1861, he collected subscriptions to fire a salute in honor of the defeat of Union forces at Fort Sumter.[43] In the months prior to the attack, Walters aided Confederate officers in establishing a recruiting station in Baltimore, channeling money through his liquor firm to financially support the recruits and their transportation to Charleston; writing to the general G. T. Beauregard, Confederate officer Louis T. Wigfall described the “financial arrangements” with Walters, explaining later that “should more [money] be necessary W. T. Walters & Co., of Baltimore, will make the advances on the draft of the officers sent. They will advance to any amount necessary.” Walters hosted Confederate officers during their visits to the recruiting station in Baltimore.[44] He also assisted in securing and delivering arms from Virginia to Confederate troops in Maryland.[45]

When Walters applied for a passport to leave the country in August 1861, rumors about his involvement with the Confederacy were swirling. “He has been active in the Secession movement I believe,” Avery disclosed, while a reporter for the New-York Tribune referred to Walters as “one of the leaders of the Secessionists.”[46] Fearing arrest for his involvement with the Confederacy, Walters resolved to travel abroad. Before boarding a ship in New York City bound for Europe, however, it appears that Walters was detained:

We had a report here yesterday that Wm. T. Walters, a wealthy and prominent merchant of Baltimore, had been arrested in New York on suspicion of being a bearer of despatches [sic] from President Jeff. Davis to the Southern Confederate Commissioners in Europe. It was known Mr. Walters left Baltimore with the intention of sailing for England on Saturday. He is a strong sympathizer with the South.[47]

Aside from the newspaper report, there is no further evidence of the arrest. Ultimately, Walters and his family traveled to Europe, where they would remain for the duration of the war.

Recent findings do suggest, however, that the suspicions leading to Walters’s arrest had grounding. This evidence appears in The Diary of George A. Lucas, a resource frequently consulted by the museum’s curators to learn about Walters’s artistic dealings abroad with his close friend and agent George Lucas. Expansive in its scope and content, the diary is a treasure trove of information about Walters’s acquisitions, travel, artist relationships, and social activities in Europe. In September 1862, Lucas recorded dining at Walters’s home in Paris with William E. Evans, Robert T. Chapman, Franklin Buchanan, and Nathaniel Beverly Tucker, all of whom had direct ties to the Confederacy; Evans, Chapman, and Buchanan were affiliated with the Confederate Navy, while Tucker served as an economic agent in Europe for the Confederate States. Two years later, Walters dined with Richard Snowden Andrews, another foreign agent for the Confederacy.[48]

Walters’s connection to Tucker and Andrews is significant. Beginning in 1861, the Confederate government sent several representatives abroad to secure legal recognition of the Confederate States of America. The main objective of these official Confederate Commissioners was to appear before government leaders in countries like Britain, France, Russia, and Belgium and broker favorable treaties of trade and commerce for the Confederacy. Simultaneously, the Confederacy also sent individual state agents for backchannel negotiations and to rally support for the Confederate cause.[49] As agents, Tucker and Andrews fell into the latter category.

The precise nature of Walters’s relationships with these men—and what, exactly, they discussed over dinner—is unknown.[50] It does appear, however, that Walters’s interactions with the Confederacy extended beyond his involvement in Baltimore; from 1862 until at least 1864, he sustained contact with Confederate officials who were trying to gain political and financial support for the South abroad.[51]

It is worth mentioning that, as far as can be determined from the historical record, Walters did not claim ownership of any enslaved individuals. Census reports, Slave Schedules, city tax records, and other Federal documents do not associate any enslaved workers with the Walters household. It is possible that Walters “rented” enslaved workers from local plantations, a practice not uncommon with Confederate-leaning Baltimoreans. To date, there is no evidence that he engaged in this practice.[52] Moreover, while Walters supported the right to secede, there is no documentation about his views towards slavery. As Lynne Ambrosini and Sarah Cash have recently argued, at mid-century it was entirely possible for Americans to uphold seemingly opposing views about patriotism, states’ rights, abolition, and slavery.[53] Walters likely fell into this category, maintaining businesses, friendships, and values that fell on both sides of the political conflict.

American Art and the Civil War

The extent to which Walters’s Southern sympathies influenced his art collection is difficult to determine. Yet just as his collecting was not separate from his businesses, it is worth considering the continuities between his paintings and his politics. Many of Walters’s business associates in the railroad and liquor industries benefited from Southern economies and shared similar political leanings. For instance, many of the officers listed in the 1859 Annual Report of the Northern Central Railway Company claimed ownership of enslaved people, including president John S. Gittings, a banker living in Mount Vernon, as well as John Merryman, a planter arrested in 1861 by the federal government involved in the controversial Ex parte Merryman court case.[54] Walters associated with similarly minded businessmen through his liquor firm, including Bethell, one of the most prominent enslavers in Louisiana, and McCoy, who relied on enslaved labor for his two mining companies in North Carolina.[55]

Walters’s ties to the South invite one to wonder what, exactly, he thought about his art collection, which primarily pictured northern landscape scenes. By 1860, Walters had an impressive collection of works belonging to the Hudson River School, a loosely defined group of artists who primarily lived in and depicted the landscapes of upstate New York.[56] Paintings by Durand, Kensett, James McDougal Hart, and Thomas Cole celebrated the uncultivated wilderness and beauty of nature. In Durand’s monumental The Catskills (fig. 3), for instance, two sycamore trees dominate the foreground, leading the viewer’s eye to an expansive view of the Hudson River Valley. The painting’s composition and attention to detail at once reveal the natural beauty of the American land and create a feeling of awe and wonder. Indeed, many Hudson River School paintings gestured toward an inherent spirituality within nature that elicited moral and existential revelations within the land.[57]

The destruction of the landscape and devastating loss of human life during the Civil War significantly impacted the production of Hudson River School paintings and the interpretations they fostered. Internal divisions within the United States threatened to destabilize artistic ambitions to build a national school of painting; “in the depths of the Civil War,” Tim Barringer has summarized, “any sense of a unified American identity was shattered.”[58] Part of the appeal of Hudson River School painting was its ability to distance viewers from pressing issues surrounding tourism, industrial development, urbanization, and increasing racial tensions felt across the country. Landscape painting often served as a kind of respite, nurturing a nostalgic desire in viewers to connect with nature and all the possibilities it offered.[59] The Civil War, with its physical and psychological traumas, challenged such hopeful and communal readings of the land.

Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826–1900), Twilight in the Wilderness, 1860, oil on canvas, 40 × 64 in. (101.6 × 162.6 cm). Cleveland Museum of Art, Mr. and Mrs. William H. Marlatt Fund, acc. no. 1965.233

One of the paintings in Walters’s collection, Church’s Twilight in the Wilderness (fig. 7), possibly foreshadowed these tensions. The work depicts a spectacular view of a blazing sunset in Maine near Mount Katahdin. Church completed the painting in 1860 and displayed it at Goupil’s Gallery in New York City, charging an entry fee of twenty-five cents. The painting was a resounding success. “It can hardly fail to attract attention for its intrinsic qualities,” The New-York Tribune declared,

the glories of a radiant sunset, the sight we all look upon so many, many hundred times, and always with renewed delight, flashes out from these clouds torn by the winds, this tender purple haze of the distant mountains, this exquisite azure of the far-off sky, and the splendor of this golden flow, which the departing sun has poured out upon the world ere the darkness covers it.[60]

Newspapers across the country, from New York, Boston, and Hartford, to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Madison, Wisconsin, reported on Church’s painting, calling it an “exquisite creation” and “a new and famous triumph.”[61]

Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826–1900), Our Banner in the Sky, 1861, oil paint over lithograph on paper, laid down on cardboard, 7 1/2 x 11 3/8 in. (19.0 x 28.9 cm). Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, acc. no. 1992.27

The dramatic sunset that attracted such praise, however, developed political overtones soon after its display and subsequent purchase by Walters. Painted on the eve of the Civil War, the work captures the Maine scene at twilight, a transitional period between sunset and night, just before total darkness subsumes the landscape. Scholars have thus interpreted the painting as “symbolically evoking the coming conflagration” of war, pointing to “the increasingly threatened state of our country’s unspoiled natural environment.”[62] Any doubts concerning Church’s political views were put to rest the next year, in 1861, when the artist painted Our Banner in the Sky (fig. 8) weeks after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter. With a similar palette and composition as Twilight, the painting boldly embeds the American flag within the landscape. Our Banner in the Sky was copied as a chromolithograph and circulated widely, inspiring patriotism and serving as a rallying call for the Union cause during the war.[63] Church’s connections to the war extended to other paintings as well; in 1861, for instance, he changed the title of his recently completed painting The Icebergs to The North, donating proceeds from ticket sales to the families of Union soldiers.[64]

Interestingly, and somewhat uncharacteristically, Walters was unsure of his purchase of Church’s Twilight in 1860. He expressed his initial trepidation over correspondence with his close friend John Frederick Kensett, disclosing, “I was in New York 10 days ago and took Church’s ‘Twilight’—a little ‘fire worksey’ perhaps.” Possibly to quell his anxiety, Walters asked Kensett for his opinion on the painting after seeing it at Goupil’s. Relieved that Kensett admired the work “just as much as it deserved,” Walters later sought his advice on where to hang it in his Baltimore home.[65]

It is reasonable to suppose that Walters’s opinions towards Twilight may have changed over time, especially as the United States edged closer to conflict. Walters acquired the painting at the dawn of the Civil War, at a time when he had deep business, financial, and social allegiances to the South. Moreover, the collector and artist had divergent political views; as Church painted his emblematic landscape Our Banner in the Sky to incite patriotic fervor among Northerners, Walters collected subscriptions in Baltimore to honor the Confederate victory at Fort Sumter. Months later, Walters would leave the country. Five years later, in 1866, he would sell Church’s painting at auction. Twilight in the Wilderness stood out among the two hundred and fifty works listed in the catalogue, with a whole page dedicated to the painting, filled with newspaper extracts from 1860. The marketing tactic, whether Walters’s or Avery’s, to whom he consigned the painting, was effective. The work sold for the impressive price of $4,300 to James Boorman Johnston, the New York financier and brother of John Taylor Johnston.[66]

The sale of the Church painting was the culmination of a larger undertaking by Walters to liquidate many of his American paintings. In February of 1864, Walters consigned over fifty of these works to Avery for a two-day sale in New York. While the catalogue did not name Walters specifically, newspapers reporting on the sale quickly identified the “resident of Baltimore (now in Europe)” as the collector.[67] Besides a few genre scenes and works of historical and mythological themes, landscape paintings dominated the pictures offered.

Walters likely had several motivations for the sale. On a practical level, many of his paintings were large in size, occupying precious wall space in his Mount Vernon home. In a letter to Kensett in 1859, only a year after Walters began seriously collecting art, he advised “I have no place for what I have got. Anything you do for me in future I think I should prefer on a smaller canvas.” Walters later appears to have passed on a painting by the artist so that it could hang in a home “more fitted in size to a work of its dimensions.”[68] Other, financial, concerns may have further encouraged the 1864 sale. With much of his money tied up in his Baltimore businesses, Walters’s finances were likely limited while abroad. The economic benefits of the auction improved his standing, allowing the collector to secure more ambitious purchases on the European art market in the following months by artists like Charles François Daubigny and Félix Ziem.[69]

The possible political implications of the sale are worthy of consideration, too. Many Hudson River School painters, like Church, were decidedly—and vocally—pro-Union. Sanford Robinson Gifford served as a national guardsman in New York’s Seventh Regiment, stationed in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore from 1861 until 1863.[70] Walters sold two paintings by Gifford at the 1864 sale. William Trost Richards also differed in politics from Walters, who disposed of three Richards paintings at the auction. Sophie Lynford has recently proposed that the “egalitarian values enshrined in American Pre-Raphaelite imagery” by Richards may explain Walters’s divestment of his work.[71]

Bierstadt Brothers, Picture Gallery, Metropolitan Fair, N.Y., 1864, stereoview. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library

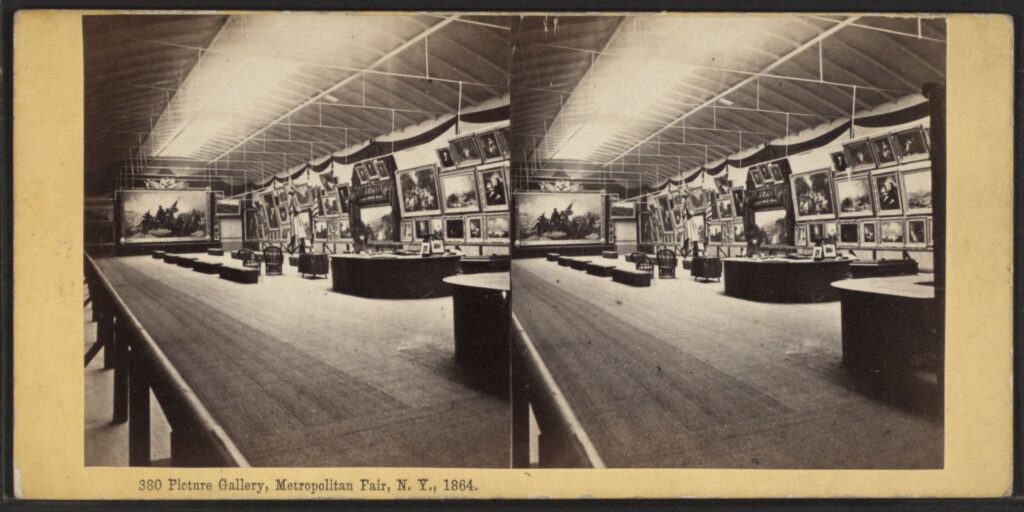

Other artists represented in the sale were even more public in their support of the Union. The Metropolitan Fair, a public event organized by New York’s Sanitary Commission to benefit Union soldiers and their families, was held less than two months after the auction. Of the many departments contributing to the cause was the Art Committee, which put on a massive exhibition.[72] Nearly four hundred paintings donated by collectors and artists hung in the large gallery (fig. 9), including works by Kensett, who co-chaired the committee. The installation celebrated American achievement in the arts, surveying its earliest history to its present. The Metropolitan Fair was part of a series of Sanitary Fairs between 1863 and 1865 that aimed to raise funds and promote loyalty to the Union. To this end, any collector and artist involved in the fair proclaimed a political allegiance that differed from Walters’s own.[73] Walters’s auction was a kind of precursor to the Metropolitan Fair, putting on view works with similar subjects and by many of the same artists.

The auction was also somewhat unusual in its timing. Though European art gained popularity among American collectors during the 1860s, Walters sold his American art collection earlier than many of his fellow collectors. Indeed, a watershed moment occurred in 1867 at the Paris Exposition, when the country’s Fine Arts Department secured just one medal, placing American painting far behind nations like France and England. Scholars consider the lackluster showing at the exposition as a turning point, redirecting collectors toward European art and prompting a younger generation of American artists to study abroad.[74] A series of sales during the late 1860s and 1870s followed, with many collectors disposing of their American paintings at low prices to make room for new European works on the market.[75]

Walters may have foreseen such developments while living abroad in Paris. The provincialism and realism that first attracted the collector to Hudson River School paintings no longer carried the same prestige as it did before the war, especially in comparison to the historical paintings of Jean-Léon Gérôme or the Barbizon scenes of Jean-François Millet. Such a realization may have prompted Walters to include European art in the 1864 auction, offering American collectors the enticing opportunity to add such works to their holdings. Shortly after the sale, Walters entered into a commercial agreement with Avery, consigning European paintings and drawings to the dealer for at least four additional auctions between 1866 and 1867. Walters therefore became a sort of collector-dealer, acting as a tastemaker to influence the American art market.[76]

Ultimately, a combination of many factors—financial, business, political, artistic, and social—likely contributed to Walters’s decision to acquire and sell his American paintings. Though this original collection is mostly absent from the museum, it offers a fascinating lens through which to consider William T. Walters’s earliest beginnings as an art collector and to recognize the enduring ties between his business, social, and political networks in Baltimore and beyond. Reconciling the absence of American art at the Walters Art Museum with its historical presence offers new information about the institution’s origins and founders, productively expanding our understanding of the collection today.

Acknowledgments

I would like to extend my greatest thanks to curator Jo Briggs for her mentorship and guidance over the course of my fellowship. Her insights, along with those of Anna Clarkson and Earl Martin, shaped my experience and scholarship in innumerable ways. I also wish to thank the late Julia Alexander for her enthusiastic support of rigorous institutional research at the Walters during her tenure as director.

[1] “About the Walters Art Museum: Past, Present, and Future,” The Walters Art Museum, last modified February 2022, https://thewalters.org/about/.

[2] There is only one extant copy of the auction catalogue, which is annotated with prices and some purchasers, at the New York Historical Society. Catalogue of a Most Valuable Collection of Pictures (New York: Henry Spear, 1864).

[3] These statistics are drawn by comparing the auction catalogue to available museum collections data. One of the few published resources about American art at the Walters is a slim catalogue produced by the museum in 1956. While Henry would continue to acquire some American artworks in the twentieth century, most of the works in the catalogue can be traced to William. Edward S. King and Marvin C. Ross, Catalogue of the American Works of Art (Walters Art Gallery, 1956); Catalogue of a Most Valuable Collection of Pictures.

[4] As William R. Johnston has explained, William and Henry Walters did not welcome publicity and sometimes destroyed archival documentation such as correspondence and receipts. See William and Henry Walters: The Reticent Collectors (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), xi–xiv.

[5] For more information on Maryland’s position and involvement in the Civil War, see Richard F. Miller, States at War: A Reference Guide for Delaware, Maryland, and New Jersey in the Civil War, vol. 4 (University Press of New England, 2015), 257–558.

[6] Many American collectors, including Walters, acquired European art during the nineteenth century as well. For one of the best sources on the early collecting of American art, see Frederic Baekeland, “Collectors of American Painting, 1813 to 1913,” American Art Review 3, no. 6 (1976): 120–166.

[7] For more on Gilmor, see Lance Humphries, “The Patronage of Robert Gilmor, Jr.: The Role of a Merchant Prince in Defining an American School of Art,” in Tastemakers, Collectors, and Patrons: Collecting American Art in the Long Nineteenth Century, eds. Linda S. Ferber and Margaret R. Laster (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2024), 20–33.

[8] See, for instance, Walters Art Museum, acc. nos. 37.171, 37.1539, 37.1536, 37.1577.

[9] See essays by Ferber, Humphries, Sarah Cash in Ferber and Laster, Tastemakers, Collectors, and Patrons.

[10] For a detailed biography of William and Henry Walters, see Johnston’s Reticent Collectors.

[11] The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 was a major progenitor for these rail lines. For more on the development of Maryland’s railroads, see Robert Gunnarsson, The Story of the Northern Central Railway: From Baltimore to Lake Ontario (Greenberg Publishing Company, 1991).

[12] After working with Samuel Hazlehurst, Walters entered a partnership with Charles Harvey to create William T. Walters & Co. Johnston, Reticent Collectors, 4–9.

[13] Walters became the president of Savannah Steamship Company in 1856 and director of the Baltimore and Havana Steamship Company in 1865. Johnston, Reticent Collectors, 9; John Thomas Scharf, History of Baltimore City and County (Philadelphia, 1881), 675–78.

[14] Brantz Mayer, Baltimore: Past and Present (Baltimore, 1871), 4, 512–13.

[15] George Peabody founded the Peabody Institute in 1857, with the library building opening in 1878. The Enoch Pratt Free Library opened in 1886, though Pratt was deeply involved in other philanthropic efforts earlier throughout the city. Mary Garrett, the daughter of B&O founder John Work Garrett, was a vocal supporter of women’s rights and education. For more on Mount Vernon Place, see “History,” Mount Vernon Place Conservancy, accessed May 15, 2024, https://mountvernonplace.org/history/.

[16] Walters commissioned at least eight works from the sculptor. Johnston, Reticent Collectors, 12; and Jenny Carson, Rinehart’s Studio: Rough Stone to Living Marble (The Walters Art Museum, 2015).

[17] The watercolors have since been removed from the albums. Miller added descriptive text to accompany each image, which often perpetuated nineteenth-century racist and sexist ideologies rooted in colonization and westward expansion. See Marvin C. Ross, The West of Alfred Jacob Miller (University of Oklahoma Press, 1951).

[18] The whereabouts of Kensett’s painting are unknown. Microfilm of Walters’s correspondence with Kensett and Durand is held by the Archives of American Art (AAA). Walters to Kensett, June 14, 1858, and December 24, 1858, John Frederick Kensett papers, AAA, reel N1534. Walters to Durand, June 8, 1858, and May 3, 1859, Asher Brown Durand papers, AAA, reel N20.

[19] Walters to Durand, March 3, 1859, AAA, reel N20. These subsequent paintings by Kensett, mentioned in correspondence, include Willow Tree, Eagle Cliffe, Hudson River, and Evening on the Hudson. Durand completed a copy of his Sunday Morning for Walters in 1860, as well as a painting titled Catskill Clove in 1859. While the latter work is similar in title to The Catskills, it appears to be a separate painting that Walters sold in 1864 to Aaron Augustus Healy. Interestingly, none of the Kensett paintings listed above appear in the 1864 auction catalogue. Another work by the artist, Lakes of Killarney, was listed, which was also purchased by Healy. Catalogue of a Most Valuable Collection of Pictures, 7.

[20] “Sale of the Ranney Pictures,” The New York Times, Dec 22, 1858. For more information on the sale, see Francis S. Grubar, William Ranney: Painter of the Early West, exh. cat. (Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1962), 11–13. A copy of the Fund Catalogue survives at the New York Historical Society, which contains inscriptions for prices and purchasers.

[21] Walters to Kensett, December 31, 1858, AAA, reel N1534.

[22] Walters to Kensett, July 20, 1859, AAA, reel N68/85.

[23] For more on the Hudson River School, see Andrew Wilton and Tim Barringer, American Sublime: Landscape Painting in the United States, exh. cat. (Princeton University Press, 2002).

[24] Avery to Hotchkiss, September 12, 1861, AAA, Durand papers, reel N20.

[25] Avery, Walters’s close friend, distributed the prints. “Domestic Art Gossip,” The Crayon 7, no. 12 (Dec 1860): 353.

[26] “Industrial Art: The 1858 Artists’ Excursion over the B&O Railroad,” Maryland Center for History and Culture, accessed May 22, 2024, https://www.mdhistory.org/industrial-art-the-1858-artists-excursion-over-the-bo-railroad/.

[27] “I take the opportunity in having met your son here,” Walters wrote, “to transmit by him a commission for a picture by you.” Walters mentions John several times throughout his correspondence to Asher Durand. Walters to Durand, June 8, 1858, AAA, reel N20.

[28] Johnston, Reticent Collectors, 14.

[29] Kensett’s draw to Iowa is unclear. He joined the railway with fellow Baltimorean Horace Abbott, who was on the board of the Federal Hill Steam Ferry Company with Kensett and owned an iron company. Interestingly, the City of Kensett in Iowa is named after Thomas Kensett. In 1869, the railroad named a locomotive the Thomas Kensett. Ruth Levitt, Kensett: Artisans in Britain and America in the Nineteenth Centuries (King’s College London, 2014), 110–11; and Donovan L. Hofsommer, “The Railroad and an Iowa Editor: A Case Study,” Annals of Iowa 41, no. 6 (1972):1073–1103. For Kensett’s involvement in the oyster industry, see Levitt, “Tin Cans and Patents,” Prologue 45, no. 3/4 (Fall/Winter 2013): 61–65.

[30] For more on Walters and the railroad, see Johnston, Reticent Collectors; and Gregg M. Turner, William and Henry Walters: Father and Son Founders of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad (Page Publishing, 2022).

[31] In the letter, Walters asks Kensett to touch up a few paintings delivered by Avery. Walters to Kensett, February 23, 1866, AAA, reel N1534.

[32] The City Passenger Railway Company, which was finally incorporated in 1862, was widely reported on from 1858 through 1860, causing much debate and scandal in Baltimore. During the trip to Annapolis, McCoy was involved in a physical altercation in the rotunda of the State Capitol. Interestingly, Walters also appears in the press from this time, mentioned in court as having disseminated private letters identifying those representing the opposition bill as abolitionists. “Investigation of the City Passenger Railway Charges,” The Sun, February 15, 1860; and Scharf, History of Baltimore City and County, 362–67.

[33] For more on McCoy, see Scharf, History of Baltimore City and County, 660–62; and Johnston, Reticent Collectors, 42–43.

[34] “Investigation of the City Passenger Railway Charges,” The Sun; and “A Useful Life Ended,” The Wilmington Messenger, November 23, 1894.

[35] For more on Henry, Wilmington, and the Joneses, see Johnston, Reticent Collectors, 112–126.

[36] Journalist William Wilkins Glenn described Walters as “a large liquor dealer, who had a large trade with New Orleans.” By mid-century, Louisiana plantations produced a quarter of the world’s sugar supply. Glenn, Between North and South: A Maryland Journalist Views the Civil War (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press), 27. For more on sugar plantations and enslavement in Louisiana, see Khalil Gibran Muhammad, “The Barbaric History of Sugar in America,” New York Times, August 14, 2019.

[37] Edwin appears in various hotel arrival announcements in New Orleans’s The Times-Picayune between 1852 and 1856. Bethell worked as Hurlbut’s agent in Louisiana as well, which is likely how he met Edwin. Announcements of Hurlbut’s shipments of sugar appear frequently in Baltimore commercial journals from the 1840s through the 1860s. “Death of Edwin Walters,” Baltimore Sun, April 20, 1897; and “Dissolution of Partnership,” Planters’ Banner, September 11, 1852.

[38] “Married,” Baltimore Sun, May 31, 1860; and “Dr. Thomas E. Torian Jr.,” Find a Grave, accessed March 12, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/53064778/thomas_e_torian.

[39] “Real Estate for Sale,” New-York Tribune, September 13, 1865; Planter’s Banner, February 27, 1869; and Carl A. Brasseaux and Keith P. Fontenot, Steamboats on Louisiana’s Bayous: A History and Directory (Louisiana State University Press, 2004), 179.

[40] “Dr. Thomas E. Torian Jr.,” Find a Grave; 1860 United States Federal Census, Ancestry.com, accessed January 26, 2024; for various records relating to Edwin Walters and the Torian children, see the Pickney C. and William D. Bethell Collection, MSS.58, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado.

[41] When William T. Walters left Baltimore for Europe in 1861, he left his firm under the management of Edwin. In 1864, Edwin expanded his interests in the liquor industry, purchasing the Orient Distiller. He withdrew from his brother’s firm in 1866, but would eventually absorb the company in 1884, changing its name to Edwin Walters & Co. “Death of Edwin Walters.”

[42] See Muhammad, “The Barbaric History of Sugar in America.”

[43] Glenn, Between North and South, 27.

[44] Wigfall to Beauregard, March 16, 1861, in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, ser. 1, vol. 1 (Washington, D.C., 1898): 276; Wigfall to L. P. Walker, March 17, 1861, in The War of the Rebellion, vol. 53, 134.

[45] The War of the Rebellion, ser. 2, vol. 1, 675. See also The War of the Rebellion, ser. 1, vol. 51, pt. 2, 24, 32–35.

[46] Avery to Hotchkiss, September 12, 1861, AAA; and “From Maryland,” New-York Tribune, June 4, 1861.

[47] “Our Baltimore Letter,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 19, 1861. In September 1861, many high-level Baltimore officials and legislators, including T. Parkin Scott, Severn Teackle Wallis, and Walters’s neighbor John Hanson Thomas, were imprisoned after Union soldiers found signatures on a document declaring their support for secession. John A. Dix to Simon Cameron, September 13, 1861, Abraham Lincoln papers, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mal1163000/.

[48] Lilian Randall identified some of these men in the appendix to the diary. See entries for September 15, 21, 27, 1862, and September 2, 1864, in Randall, The Diary of George A. Lucas: An American Art Agent in Paris, 1857–1909, vol. 2 (Princeton University Press, 1979), 141, 183.

[49] Chapman, on the other hand, had ties to James Mason, a Confederate Commissioner in England, who selected the lieutenant to deliver the Confederate Seal to the United States. “Great Seal of the Confederacy,” National Museum of American History, accessed Dec 14, 2023, https://www.si.edu/object/great-seal-confederacy:nmah_412912; and Howard Jones, Blue and Gray Diplomacy: A History of Union and Confederate Foreign Relations (University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

[50] As a businessman with ties to the South, Walters was likely sympathetic to the Confederate Commissioners’ cause, which, in part, was prompted by the government’s blockade of Confederate ports to prevent trade with Mexico, Europe, and various ports in the Caribbean. In addition to limiting the Confederacy’s access to arms, the blockade aimed to curtail exports of cotton abroad, thus crippling the Southern economy. “The Blockade of Confederate Ports, 1861–1865,” Office of the Historian, accessed February 8, 2024, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1861-1865/blockade#:~:text=During%20the%20Civil%20War%2C%20Union,war%20materiel%20into%20the%20Confederacy.

[51] This evidence goes directly against what Walters asserts in a letter to Simon Cameron, Lincoln’s Secretary of War, in 1864. Walters to Cameron, December 20, 1864, Walters Art Museum Archives.

[52] Walters’s neighbor, John Hanson Thomas, “rented” at least one enslaved person in addition to his enslaved household staff. The Sun, January 17, 1852.

[53] Lynne Ambrosini, “Nicholas Longworth: Early Midwestern Activist Art Patron,” in Ferber and Laster, Tastemakers, Collectors, and Patrons, 91; and Sarah Cash, “‘Encouraging American Genius’: The Corcoran Gallery of Art, from Private Collection to Nation’s Art Museum,” in Tastemakers, Collectors, and Patrons, 114.

[54] Fifth Annual Report of the President and Directors of the Northern Central Railway Co. to the Stockholders for the Year 1859 (Baltimore, 1860). Chief Justice Roger B. Taney wrote the opinion for the case. Walters would later commission a sculptural replica of Taney, which was gifted to the City of Baltimore and placed in Mount Vernon Place. The sculpture was removed in 2017 due to Taney’s involvement in the Dred Scott decision.

[55] The 1860 Slave Schedule lists Bethell as owning 175 enslaved individuals. “St. Mary Parish, Louisiana Largest Slaveholders from 1860 Slave Census Schedules,” transcribed by Tom Blake, published 2001, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~ajac/genealogy/; a description of McCoy’s use of enslaved labor appears in Scharf, History of Baltimore City and County, 661–62.

[56] The name was not used by the artists themselves, but rather came about in the 1870s. The group’s influence extended beyond Hudson River Valley to various sites in New England, the Ohio River Valley, and beyond. See Kevin J. Avery, “The Hudson River School,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hurs/hd_hurs.htm; and Wilton and Barringer, American Sublime.

[57] Between 1855 and 1856, Durand published his “Letters on Landscape Painting,” encouraging artists to paint nature accurately to access higher moral and spiritual truths. Avery, “The Hudson River School.”

[58] Wilton and Barringer, American Sublime, no. 2, 72.

[59] Wilton and Barringer, American Sublime; “The Making of the Hudson River School,” Albany Institute of History and Art, online exhibition, accessed November 19, 2023, https://www.albanyinstitute.org/online-exhibition/the-making-of-the-hudson-river-school.

[60] “Twilight in the Wilderness,” New-York Tribune, June 13, 1860.

[61] “Twilight in the Wilderness,” Boston Evening Transcript, June 28, 1860; Baton Rouge Tri-Weekly Gazette and Comet, July 22, 1860. See also Hartford Courant, June 8, 1860; and “A New Picture by Church,” Wisconsin State Journal, June 15, 1860.

[62] Mark Cole, “Twilight in the Wilderness: A Closer Look at an American Masterpiece,” Cleveland Art 54, no. 5 (September/October 2014): 4.

[63] Eleanor Jones Harvey, The Civil War and American Art, exh. cat. (Yale University Press, 2013), 31–38; and “Our Banner in the Sky,” Terra Foundation for American Art, accessed May 2, 2024, https://collection.terraamericanart.org/objects/217?_ga=2.134864945.1723831616.1716917327-86778822.1716917327.

[64] “Rally ‘Round The Flag: Frederic Edwin Church and the Civil War,” Antiques and Fine Art 11, no. 1 (Spring 2011): 209.

[65] “By the way,” he wrote, “would you hang it in the strongest light—say over the ‘Duel’ [The Duel After the Masquerade] next the window where it would bring out the details—or would you hang it say where your ‘Eagle Cliffe’ is now?” Walters to Kensett, [June] 1860; July 12, 1860; and July 23, 1860, AAA, reels N68/65 and 1534.

[66] While Johnston has claimed that Walters sold Twilight at the 1864 sale, first mention of the sale of the work in the press appears in 1866. Entry number 136 in the 1864 catalogue does list a painting by Church titled Twilight, Mt. Desert. Handwritten inscriptions in the catalogue indicate this painting sold for $1,950 to an individual named “Wheeler.” While certainly of similar subject, it does not appear that the painting in the 1864 sale was Twilight in the Wilderness, which was reported in multiple newspapers two years later and whose title prominently appears in the 1866 catalogue. See, for instance, Iowa Transcript, March 21, 1866; Buffalo Commercial, April 6, 1866; and Philadelphia Inquirer, March 12, 1866. Johnston eventually sold the work in 1876 to John Work Garrett, who lived with his daughter Mary on Cathedral Street in Baltimore. The painting is now in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

[67] See, for instance, “Fine Arts,” Brooklyn Union, February 6, 1864.

[68] Walters to Kensett, June 27, 1859, and July 20, 1859, AAA, reel N68/85.

[69] As Johnston has suggested, Walters’s financial limitations forced the family to economize on travel throughout Europe in 1861. Reticent Collectors, 27, 35.

[70] Kevin Avery, “Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823-1880),” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 2009, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/giff/hd_giff.htm.

[71] “While the reason for Walters’s sale of Richards’s paintings may be attributed to a change in taste, given that Richards moved in abolitionist circles,” Lynford argues, “Walters’s divestment may also be explained by a difference in wartime politics between artist and collector.” “Patrons of Reform: Collecting the American Pre-Raphaelites,” in Ferber and Laster, Tastemakers, Collectors, and Patrons, 100.

[72] The fair raised over 1.3 million dollars, with the Art Committee contributing nearly eighty-four thousand dollars, one of the largest contributions by a single department. Metropolitan Fair in Aid of the United States Sanitary Commission (New York, 1864).

[73] Held in cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, Indianapolis, and New York on behalf of the United States Sanitary Commission, Sanitary Fairs were extremely popular civilian-organized events that raised funds for the Union Army. For more on the Metropolitan Fair, see Ferber, “Introduction: Collecting American Art During the Long Nineteenth Century,” in Ferber and Laster, Tastemakers, Collectors, and Patrons, 7–10; and “The Art Gallery of the Sanitary Fair,” New York Times, April 11, 1864.

[74] Carol Troyen, “Innocents Abroad: American Painters at the 1867 Exposition Universelle, Paris,” American Art Journal 16, no. 4 (Autumn 1984): 4; and Ferber, “Introduction,” 11–12.

[75] An important sale occurred in 1876, when Johnston was forced to sell his collection due to financial losses suffered during the panic of 1873. During the sale, 57.3 percent of European paintings sold for over $1,000, compared to only 16.2 percent of the American works. Olyphant’s collection of American art fetched even lower prices a year later. Baekeland, “Collectors of American Painting,” 138–143.

[76] As Johnston explains, the agreement launched Avery’s career as a dealer. Reticent Collectors, 39.