In 2024 the Walters Art Museum celebrated its ninetieth year as a cultural hub in the heart of Baltimore City. Henry Walters (1848–1931) gifted a collection of twenty-four thousand objects at the time of his death in 1931. When what was then known as the Walters Art Gallery was set up in 1934 “for the benefit of the public,” the collection encompassed works spanning from antiquity through then present times. Since then, the museum’s collection has grown by one-third as much in size through donations, bequests, and purchases. Now, as the museum moves into the second quarter of the twenty-first century, it is refining its contemporary collecting strategy, building on the holdings established by Henry and his father, William T. Walters (1819–1894), while expanding to include the contributions of talented artists of diverse cultural backgrounds and genders unrepresented in the foundational collection.

Many factors, from educational and economic to social and political, influenced how the father and son built their collections. They were well-established white, Protestant Baltimorean businessmen who were able to thrive as American society sped toward modernization at the turn of the century, as well as during the vicissitudes of the early twentieth century.[1] Kristen Nassif, former Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow, relates in her essay in this volume how some of William T. Walters’s early acquisitions included those by his contemporaries Alfred Jacob Miller, William Henry Rinehart, Asher Brown Durand, John Frederick Kensett, and Frederic Edwin Church. As Nassif explains, although Walters later sold the majority of these, he continued to acquire works by artists who were active in his day as well as historical pieces.[2]

A Contemporary Art Collecting Strategy for the Twenty-First Century

Today, the museum’s current strategy focuses on enhancing the holdings of historical art and advancing the tradition of collecting contemporary art to ensure that the Walters continues to thrive and create space for dialogue, reflection, and new artistic expression. In tandem with a former curatorial collecting strategy developed in 2020 and ongoing work the museum is doing through community advisory groups and audience evaluation, curators have been thinking about how the general public perceives objects in museums today and looking for ways current voices can help to build bridges to the historical collection and augment it in relevant and meaningful ways.[3] Recent audience evaluations at the Walters Art Museum have provided information about how the inclusion of contemporary artworks and the addition of related didactics and interactives may impact visitor experience; this research has informed curatorial conversation about gallery installation and exhibition content. The recent addition of several important contemporary works to the museum’s holdings demonstrates our serious commitment to prominently incorporating the work of contemporary artists in the context of the historic collection, while building upon our ongoing dedication to embedding stories in our galleries that resonate with our audiences.

The twenty-first-century collecting strategy goes hand in hand with other work the Walters Art Museum has been engaged in for decades. Strides toward creating a more inclusive representation in the collection were notably seen with the landmark exhibition Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe in 2012 and more recently, in 2022, with Activating the Renaissance, which featured six living artists, including local BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) artists. The work of these artists, on loan, appeared alongside Renaissance paintings and sculpture from the Walters collection in the museum’s permanent collection galleries.

Findings from the museum’s Evaluation and Audience Impact team showed that visitors felt Activating the Renaissance provided a welcome opportunity for deeper conversations around issues of race and representation in art museums and that BIPOC museum attendees made personal connections and felt welcomed. Notably, 62 percent of the Walters’ BIPOC audience were first-time visitors to the museum, with the exhibition being their reason for coming. By continuing to foreground more inclusive representation through acquisitions, installations, and exhibitions, the institution seeks to strengthen relationships with active artists, cultivate a more diverse visitorship, and foster a deeper sense of belonging.

Meaningfully engaging museum visitors, both new and established, in the world of art may require connecting or relating the works of art to an attendee’s own life experience. New works can be stimulating in and of themselves, but when they include a facet familiar to museum-goers they can also provide a bridge to the appreciation and understanding of unfamiliar historical collections or works from less known cultures. In the twenty-first century, Walters curators evaluate whether the addition of a contemporary work to the collection will lead to deeper public understanding of the existing collection. They ask: Is there a direct connection to a specific work of art in the collection? Does the work deal with a concept or process that will make it meaningful when displayed in the context of the historical collection? What is the quality and significance of a work of art, and what is its capacity to augment a particular collection area in a way that will resonate with both today’s and future museum audiences?

A goal of the current collecting strategy is to achieve a balance between works by living artists with a local connection and works by artists of national or international renown.[4] This balance is part of a strategic effort to bring local artists and new or underrepresented voices into the context of a larger conversation with both contemporary and much older art, elevating the status of the work of today’s artists as they share space in the museum with renowned works created by artists of the past. While the significance or potential social, cultural, or educational value is critical in evaluating contemporary art for the collection, so is the physical condition of the works and the museum’s ability to display, store, maintain, and conserve them. For this reason, the materials integral to each work—whether ephemeral material such as fresh fruit or dried flowers, non-archival material such as adhesives that can damage artworks over time, or technological components that may be extremely difficult to source and replace in the future—are taken into account prior to the museum’s decision to acquire.

Integrating Contemporary Works

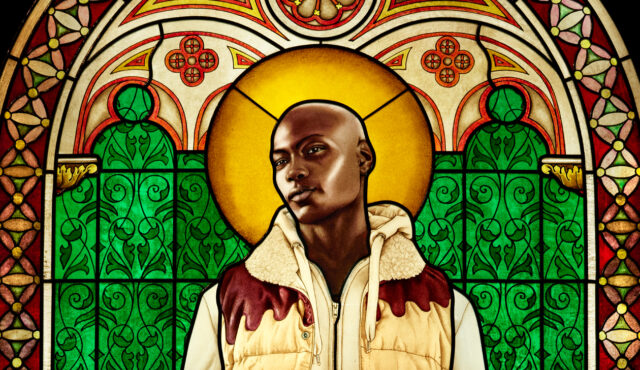

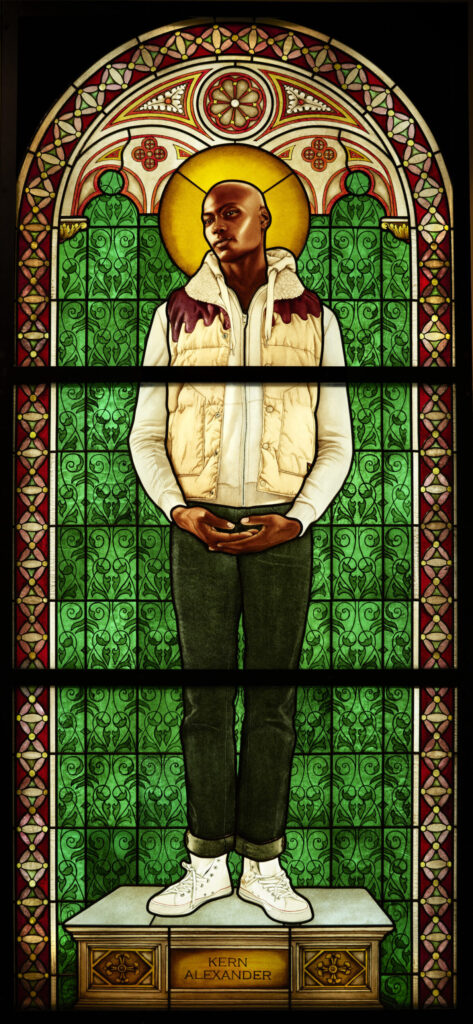

Recent acquisitions embody the museum’s twenty-first-century collecting strategy and demonstrate the museum’s approach to integrating contemporary art into the collection.[5] A major addition to the collection, Saint Amelie is a 2022 acquisition by world-renowned American artist Kehinde Wiley (born 1977) that exemplifies several goals for the expansion of the museum’s holdings. This rare example of Wiley’s stained glass augments the museum’s historical collection, creating dialogue between past and present. This special work adds both a Black voice and representation of a twenty-first-century Black subject, foregrounding a demographic that is underrepresented in the collection yet makes up a majority of Baltimore’s population (fig. 1). As such the work represents the museum’s expansive approach toward representing more diverse perspectives in the collection.

Kehinde Wiley (American, born 1977), Saint Amelie, United States (Brooklyn) and Czech Republic (Lubenec), 2014, painted and stained glass, 98 7/8 × 45 7/16 in. (251.2 × 115.4 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by William A. Bradford and the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 2022, acc. no. 46.92

The striking Saint Amelie panel belongs to Wiley’s small but luminous body of work in stained glass capturing the likenesses of young Black residents of Brooklyn, New York. The panel, one of twelve freestanding stained-glass works to be made from Wiley’s designs, references the form, composition, figural pose, and framing of historical stained-glass windows. However, Wiley has replaced what would have been images of Christian saints in a particular type of historical stained glass with contemporary subjects. The addition of Wiley’s work to the Walters’ collection creates a dialogue with the museum’s renowned historical holdings of stained glass, inviting conversation between past and present. It is also a most fitting addition to Baltimore in that the city is known for significant stained-glass works produced by John LaFarge and Louis Comfort Tiffany and is the site of stained-glass art studios today.

Unidentified Flemish artist, Saint Andrew and a Donor, Belgium (Flanders), 1520–1540, stained glass, 27 5/8 × 18 3/4 in. (70.2 × 47.6 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by the S. & A.P. Fund, 1958, acc. no. 46.81

A comparison of Saint Amelie with a sixteenth-century Flemish image of Saint Andrew in the collection of the Walters demonstrates how Wiley has situated his work within the long European Catholic tradition of producing images of saints framed within an arched space in predominantly rich red, green, yellow, and blue stained glass (fig. 2). Wiley was especially inspired by stained-glass windows and studies by the French Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780‒1867), whose works in other media are represented in the collection of the Walters (fig. 3).[6] The link with, but deviation from, a tradition represented in the collection assures that the addition of this contemporary work aligns with the museum’s aim to add select artworks that increase the ways the collection can be interpreted by visitors today and in the future.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French, 1780–1867), The Betrothal of Raphael and the Niece of Cardinal Bibbiena, 1813–1814, oil on paper mounted on canvas, 23 1/4 × 18 5/16 in. (59.1 × 46.5 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, 1903, acc. no. 37.13

Wiley collaborated with artisan stained-glass manufacturers in the Czech Republic (now called Czechia) working in traditional hand-painted techniques. The title of his piece, Saint Amelie, helps to make its connection to the stained-glass tradition explicit, but the subject is one of our own times, Kern Alexander, a model the artist frequently used in his work. Wiley posed Alexander standing angelically in twenty-first-century garb—a sweatshirt, puffer vest, jeans, and sneakers. By placing his model in a composition and stance associated with historical European works, Wiley treats his Black subject with the dignity and materials traditionally reserved for Christian works that largely represent Christian martyrs as white. With Saint Amelie, the artist makes an African American, someone largely absent in the museum’s historical collection, present and accessible. He leads viewers to contemplate a young Black man with the same reverence as that held for Catholic saints. Considered in the context of daily life for young Black individuals in America, the work takes on special meaning as a representation of young Black men who have lost their lives solely because their appearance was perceived as threatening.

Roberto Lugo (American, born 1981), Slave Ship Potpourri Boat, United States (Philadelphia), 2018, porcelain, china paint, luster, 11 1/2 × 9 × 3 1/2 in. (29.21 × 22.86 × 8.89 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 2018, acc. no. 48.2882

Roberto Lugo (born 1981) is another artist who strives to make the invisible visible in his work.[7] In 2018 the Walters acquired ceramic works by this Philadelphia-based artist, activist, and educator that were inspired by historical objects in the Walters collection. By blending traditional forms and practices found in the Walters collection with contemporary color and imagery, the artist invites contemporary audiences into conversation with traditional works, offers insight into lived experiences previously underrepresented in the museum’s holdings, and contributes to building a more diverse and inclusive collection. Lugo’s Slave Ship Potpourri Boat (fig. 4), for example, revisits and reinterprets from a Black twenty-first-century lens what potters at Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory in 1764 manifested as a charming fishing boat, featuring details of the rigging, portholes, and a flag (fig. 5). The Sèvres porcelain, a vase for potpourri, was acquired by Henry Walters. The imagery by Jean-Louis Morin includes a marine-themed trophy on the back. In Lugo’s hands the boat has been transformed into a slave ship, with figureheads of white men at both bow and stern, a reinterpretation that asks the viewer to acknowledge that much of the wealth that built the fortunes of North American and European elites was the result of the slave trade and the forced labor it fed. Lugo’s potpourri boat introduces visual imagery that evokes the rank smell of people inhumanely packed in close quarters and denied basic hygiene, not to mention the stench of inequality, racial injustice, and the poverty their enslavement engendered, to the form of a vessel originally intended to perfume the air. His hand-painted details feature a view into the ship’s hold crammed with enslaved people on one side of the vessel and Baltimore’s twenty-first-century skyline on the other.

Jean-Claude Duplessis le Père (French and Italian, ca. 1695–1774), designer (?), Jean-Louis Morin (French, 1732–1787), decorator, Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory (French, active 1756–present), manufacturer, Potpourri Vase (Vase potpourri à vaisseau), France (Sèvres), 1764, soft paste porcelain, overglaze enamels, gilding, 17 13/16 × 13 3/4 × 6 13/16 in. (45.2 × 35 × 17.3 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, 1928, acc. no. 48.559

New acquisitions such as those by Wiley and Lugo are, in part, motivated by our commitment to ensure that the collections more fully represent diverse socioeconomic groups and underrepresented communities. Curators intend that the addition of these works to the museum’s galleries will increase engagement with the museum and its collections by groups who have not felt included in museums. Among these groups is Baltimore’s growing Latino population. The United States Census Bureau 2020 report records 45,927 Latino/Hispanic people living in Baltimore City alone, an increase of close to 20,000 in a decade.[8] In 2025 the museum for the first time opened long-term galleries dedicated to showing permanent collections of Latin American art. Adding contemporary perspectives throughout the art shown in these galleries is a critical element of this presentation. As part of this effort, the museum recently acquired a work by Nicaraguan American artist Jessy DeSantis (born 1991), who lives and works in Baltimore.

Jessy DeSantis (American, born 1991), Cintli, Corn, Maíz, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 48 1/16 × 36 × 1 9/16 in. (122 × 91.5 × 4 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase, 2022, acc. no. 37.2951

DeSantis’s large acrylic painting, Cintli, Corn, Maíz, is of an ear of corn with multicolored grains still on the cob (fig. 6). The husks surrounding the ear of corn transform into the long tail feathers of a quetzal bird, native to Central America. Corn remains central to many Indigenous and mestizo Latin American cultures today, and the painting, like many historical artworks, suggests a metaphorical connection between plants and animals of the Americas. Corn is a food that DeSantis grew up eating. Later growing it and learning more about its history, mythology, and ties to food sovereignty helped the artist reconnect with their community during the isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic.[9] This intimate and intense connection made the subject an inspiration for DeSantis’s art.[10]

Unidentified Mexica (Aztec) artist, Maize Deity, Mexico, 1400–1521, volcanic stone, traces of red pigment, 21 5/8 × 7 11/16 × 5 3/4 in. (54.86 × 19.56 × 14.61 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Gift of John G. Bourne, 2014, acc. no. 2009.20.199

Cintli, Corn, Maíz, created by an artist of Latin American heritage, becomes especially meaningful when viewed in tandem with the collection’s Mexica deity of corn sculpture that dates back six to seven hundred years (fig. 7). The sculpture testifies to the central place of corn in the spiritual and cultural belief systems of the Indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica. It depicts the Mexica (Aztec) corn goddess Chicomecoatl (Seven Serpent), identifiable by her square headdress and nose ring. Her elaborate headdress of corn husks and possibly sacred quetzal feathers, when viewed with DeSantis’s painting, points to deep historical connections for many citizens of Baltimore and beyond.

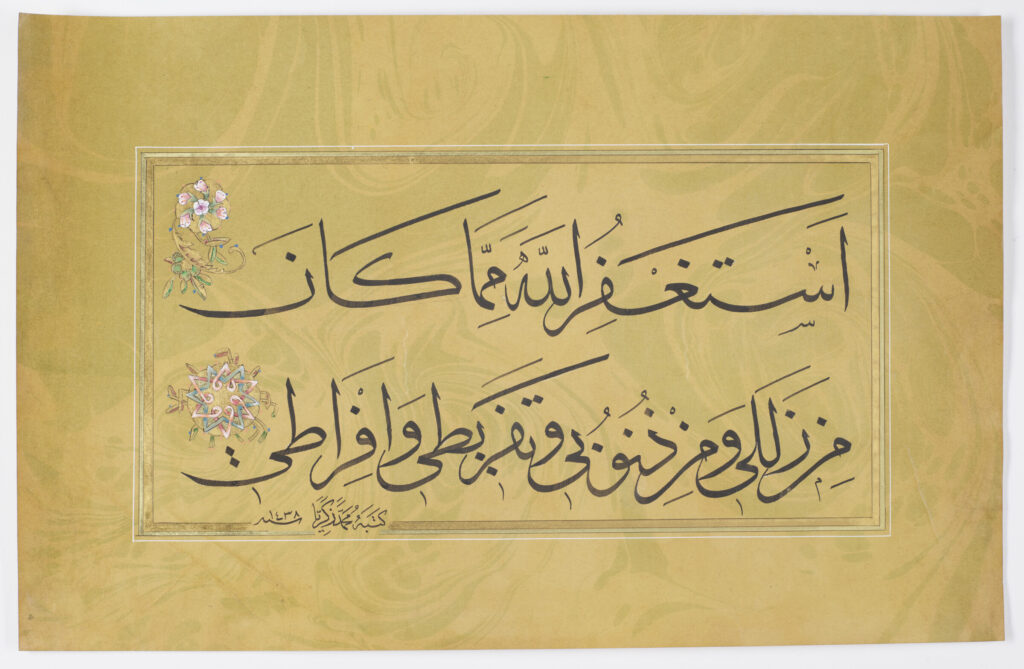

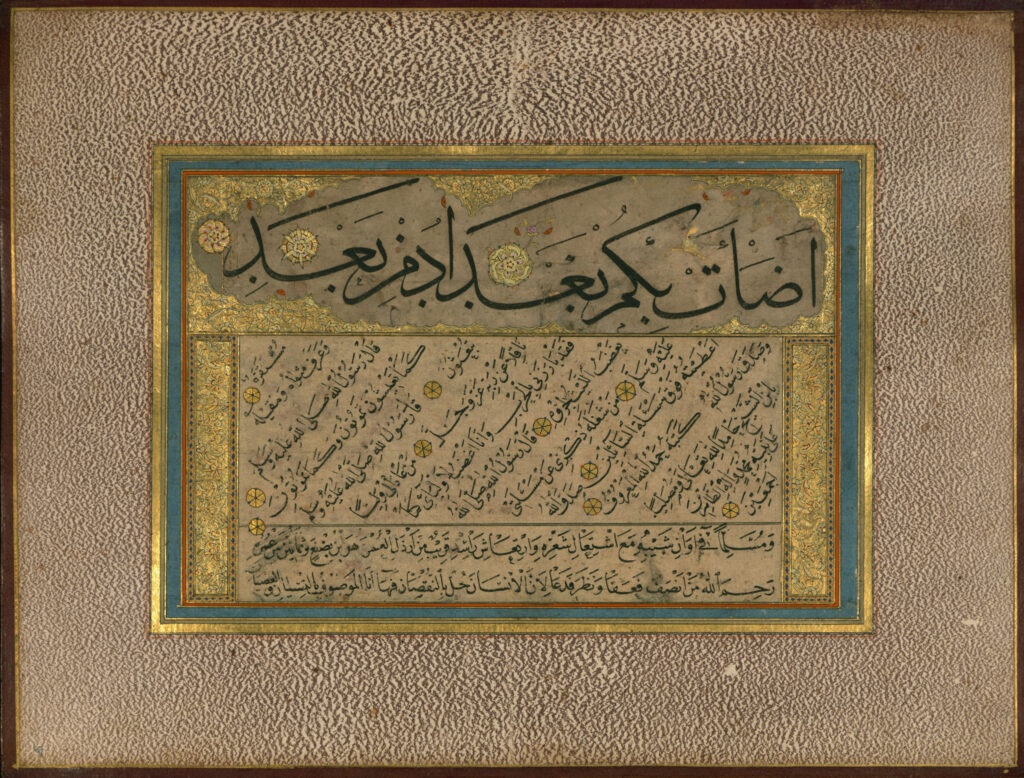

Mohamed Zakariya (American, born 1942), Entreaty, 2017, ink, gouache, and gold on ebru (marbleized ahar paper), 8 ⅜ × 10 in. (21.3 × 25.4 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase, 2022, acc. no. W.961

Another work that represents a step toward achieving the Walters’ goal toincorporate artwork by local artists into the collection is Entreaty (fig. 8), a recent acquisition of calligraphy by Mohamed Zakariya (born 1942), who lives and works near Washington, DC. The calligraphic rendering of an Islamic entreaty comprises two lines of Arabic in an artfully written monumental script called thuluth (Turkish: sülüs) that can be translated as “I ask the forgiveness of God for my stumbles and for my sins and for what I neglected and for what I did too much of.” This work by a local artist supports and calls attention to strong connections to Muslims living in the DC-Maryland-Virginia region. Collecting calligraphy by Zakariya elevates the status of the work of a twenty-first-century Muslim artist at the Walters, where it joins a strong collection of Islamic art, including calligraphy. Further, inclusion of Zakariya’s work in the collection facilitates a larger conversation about the survival of historical traditions like calligraphy in the contemporary art world and their relation to the museum’s long established collection.

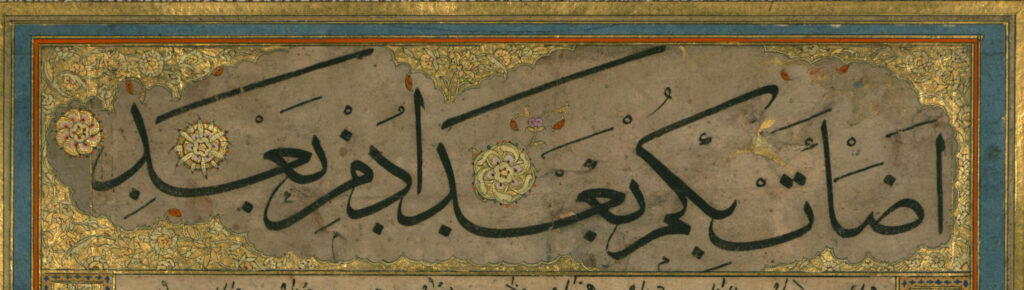

Accordion Album of Calligraphies by Şeyh Hamdullah (d. 1520), Türkiye, 16th-century calligraphies, compiled into the album in the 18th century, ink and paint on paper mounted on thin pasteboard, 9 1/16 × 11 13/16 in. (23 × 30 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, before 1931, acc. no. W.672

More specifically, this recent acquisition has a direct tie to early modern Ottoman book arts represented in the museum’s collection that include both writing and illumination. In addition to writing the calligraphy, Zakariya also prepared the paper, colored it with traditional ebru (marbling), and added illumination in a manner reminiscent of the eighteenth-century Ottoman baroque style. His signature and the date (1438 AH / AD 2017) also appear on the page. Both the horizontal format and a similar scale of writing appear in an accordion format album (muraqqa’) that includes nine collated works attributed to Şeyh Hamdullah (died 1520), known as the “father of Ottoman calligraphy” (fig. 9). Albums of this kind were compiled as first-hand study models for dedicated students of calligraphy.

Accordion Album of Calligraphies by Şeyh Hamdullah, W.672, folio 5a detail of title in thuluth script

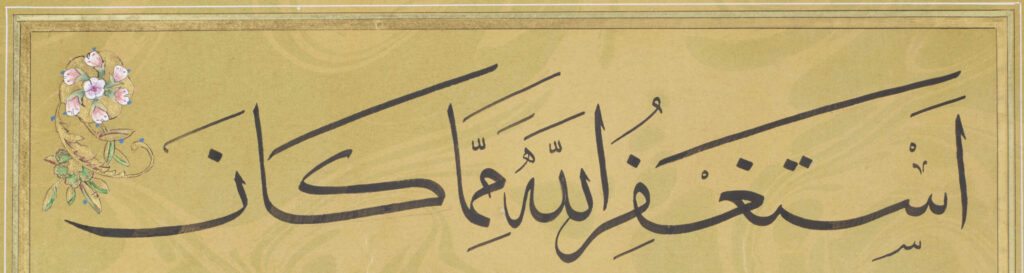

Zakariya follows the tradition established by Şeyh Hamdullah and handed down directly from master to student, who then becomes teacher and so on. As such Zakariya is a link in a linear chain of transmission (silsila, lit. “chain”) from Şeyh Hamdullah to the present. Zakariya, who today is an internationally renowned calligrapher, converted to Islam and first taught himself Arabic-script calligraphy, but ultimately was taken on as a student in Türkiye by Hasan Çelebi (born 1937). Çelebi himself had studied with the last of the Ottoman calligraphers, Hamid Aytaç (1891‒1982). A comparison of Entreaty and the title of a work in the album that bears the signature of Şeyh Hamdullah demonstrates how Zakariya uses his reed pen to capture the elegant, fluid, and elongated calligraphic style of the renowned master’s thuluth script (fig. 10, fig. 11).[11] The addition of Zakariya’s Entreaty to the collection has enabled the Walters Art Museum to share with visitors examples of a stylistic tradition of calligraphy passed down from master to student for over half a millennium across continents.

Entreaty, W.961, detail of title in thuluth script

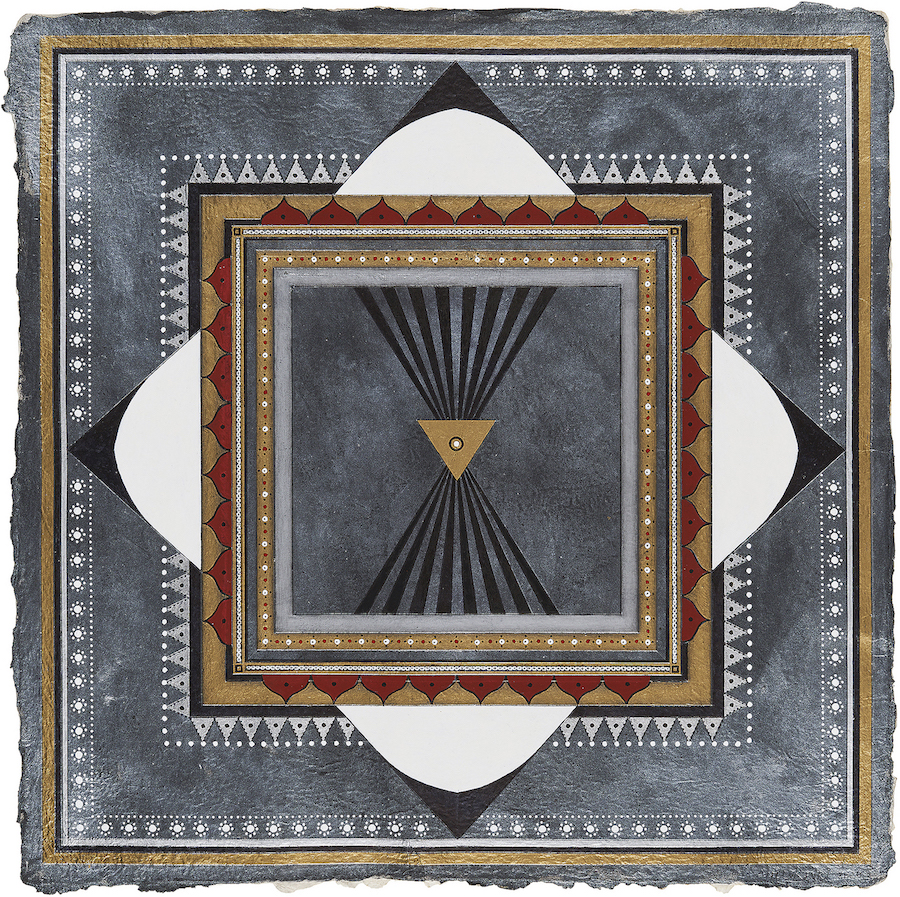

While Mohamed Zakariya’s work provides a strong example of how artistic traditions are transmitted over huge spans of time and great distances to our own neighborhood today, a recent gift (fig. 13) created by the late artist Anil Revri (1956–2023) is a testament to an artist who combined media and elements of more than one spiritual tradition to make work that is novel yet familiar and uniquely powerful at once. Revri lived in Washington, DC, so like Zakariya, he was based in the region.

Chakrasamvara Mandala, Tibet, early 15th century, glue tempera on cloth, 21 3/4 × 22 1/4 in. (55.25 × 56.5 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Gift of John and Berthe Ford, 2019, acc. no. 35.328

Revri’s work is steeped in diverse Asian religious and philosophical traditions, including Tibetan Buddhism. For centuries, mandalas have been designed as meditational devices for students of Tantric Buddhism.[12] Tantric, or mystical spiritual, practices are passed on from teacher to student. Mandalas are visualization tools that feature repetitive geometric shapes, religious iconography, and the symbolic use of color for spiritual advancement. Practitioners use mandalas like the Chakrasamvara Mandala, with its flat diagrammatic, palace-like structure meant to be visualized in three dimensions, to help them expedite their progress toward enlightenment (fig. 12).

Anil Revri (Indian American, 1956–2023), Geometric Abstraction 9, 2020, mixed media on handmade paper, 18 × 18 in. (46 × 46 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase, 2022, acc. no. 37.2947

Composed of two square fields in silver color and one in white with black, Revri’s mandala-like mixed-media Geometric Abstraction 9 features four lobed corners that dominate the composition, each smaller than the next and superimposed over the last (fig. 13). There is a gold triangle with a white dot encircled by black at the center with eight black lines radiating out from the top and bottom of the triangle. Square, concentric decorative bands of gold, black, and white, as well as dots and dot patterns of black, white, and brick red, embellish the composition. Brick-red stylized lotus petals ornament the central gold field. While at first glance his work may appear merely abstract, the artist’s aesthetic references Tibetan mandalas as well as Islamic imagery, including that found in architecture. Patterns of symmetrical designs that include repeating geometric shapes such as circles, squares, and stars are common elements of Islamic architecture. Divine order is believed to be expressed in mathematical principles such as symmetry, proportion, and tessellation—the repetitive nature of these Islamic geometric patterns is often associated with the concept of infinity and the eternal nature of God. Within Islamic tradition also is the belief that both the creation and contemplation of these patterns can lead to spiritual transcendence. Revri taps these traditions, combines them, and filters them through his own personal visual vocabulary. A comparison of Geometric Abstraction 9 with the Chakrasamvara Mandala highlights that both compositions are organized around a central axis. This feature allows this contemporary work, like a Buddhist mandala, to function as a meditational piece that facilitates a journey. Revri’s work was created to inspire a journey into the void, which for the artist held the key to deep emotions such as love, fear, and desire.

Fujikasa Satoko (Japanese, born 1980), Seraphim, 2015, stoneware ceramic, slip glaze, 25 × 23 1/2 × 17 in. (63.5 × 59.69 × 43.18 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Gift of Betsy and Robert Feinberg, 2015, acc. no. 49.2831

In a similar vein, the work of many Japanese ceramic artists active today has direct links to earlier East Asian pottery traditions, but they tackle completely new aesthetic and technical ground. In recent years the Walters acquired several contemporary Japanese vessels made in materials that have long been favored by Japan’s craftspeople. One outstanding example, a 2015 gift of Betsy and Robert Feinberg, is Seraphim, a work of the female potter Fujikasa Satoko (born 1980) (fig. 14). Like many Japanese artists both past and present, Fujikasa takes her inspiration from nature and the changing effects of time. Wabi-sabi, a quality that suggests ephemerality and is likened to the humble beauty of something that has become weathered or corroded over time, has been sought out by many Japanese ceramic artists and is seen particularly in ceramic pieces used in some types of traditional tea gatherings. A raku ware tea bowl acquired by one of the museum’s founders captures this essence in its uneven and pitted surface (fig. 15).

Tea Bowl, Japan (Kyoto), 19th century, earthenware ceramic, glaze (raku), H: 3 3/4 in. (9.6 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by William T. or Henry Walters, before 1931, acc. no. 49.2119

Many of Fujikasa’s works, including Seraphim, painstakingly built up by hand with coils of clay, conjure billowing winds or undulating rivers and seas. But it was ultimately seeing natural formations themselves captured in photography of Antelope Canyon, located in the United States of America on Navajo land in Arizona, that led her to fully formulate her artistic vision (fig. 16). The location is famed for its dynamic sandstone formations created by the natural erosion resulting from monsoon rains and blowing sand. A comparison of the landscape of Antelope Canyon with Seraphim makes the aesthetic connection—a flowing balance of soft curves and sharp edges associated with wear over time—unmistakable.

Lower Antelope Canyon, LeChee, Arizona. Photo by Reed Geiger

From a young age Fujikasa was exposed to a broad range of historical and modern art from around the world.[13] However, it was only when she entered Tokyo University of Fine Arts that she was introduced to traditional Japanese ceramic techniques and decided to develop her natural affinity for clay. Her inspired vision and familiarity with Japan’s ceramic traditions led her to select the sandy clay from Shigaraki in Shiga prefecture, the same clay used for Japan’s famed ancient Shigaraki jars, for the production of Seraphim and related works. After coating Seraphim’s completed form with a white slip, the potter artfully achieved her goal of capturing nature’s transformative life force.

As a final example, a recent acquisition by the artist Herbert Massie highlights the Walters Art Museum’s twenty-first-century collecting strategy’s emphasis on local artists embedded in our community. The Walters defines local artists as those connected to the DC-Maryland-Virginia region, with a prioritized emphasis on artists connected to Baltimore City, like Herbert Massie (born 1954). Massie is a lifelong resident of and educator in Baltimore who is celebrated for his public art projects. As an artist, Massie models the kind of community activism that the museum seeks to foster and support in strengthening its own relationships to local communities.[14]

Herbert Massie (American, born 1954), Reflections of Sybby Grant, 2018, glazed stoneware, wood paneling, glass tiles, mirror, 5 panels (3 shown): 1 of 5 (large oval) 47 × 94 in. (119.38 × 238.76 cm), 2 of 5 (large oval) 47 × 94 in. (119.38 × 238.76 cm), 3 of 5 (small oval) 47 × 30 in. (199.38 × 76.2 cm), 4 of 5 (small oval) 47 × 30 in. (199.38 × 76.2 cm), 5 of 5 (long rectangular) 10 × 82 × 25 in. (25.4 × 208.28 × 63.5 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase, 2023, acc. no. 43.57

In 2018 the Walters Art Museum commissioned Massie and the art program Jubilee Arts to do a community art project that resulted in Reflections of Sybby Grant, a work that incorporates over two hundred stoneware plates created by a diverse range of members of the Baltimore community including schoolchildren, seniors, library patrons, and members of the Walters Art Museum staff (fig. 17). Massie hosted a series of workshops with these community members to create stoneware plates, many of which he then used as a major component of mirrored mosaic panels.

Sybby Grant, the woman who inspired this project, was the enslaved cook of Dr. John Hanson Thomas and his family, who were the first residents of the house at One West Mount Vernon Place, now one of the buildings that comprise the Walters Art Museum campus. Reflections of Sybby Grant was designed for the house in which Grant lived and worked. It is therefore especially fitting that it was purchased as a work for the Walters collection in 2023. Currently on view in One West Mount Vernon Place, it is a reminder of the complex and troubled histories that are embedded in the buildings that house the museum’s collection. Moreover, Massie envisioned the connection between mosaic art and dinner plates, and through the communal act of creating, the work brought and continues to bring people together to share experiences and conversation. Gina Borromeo, former Senior Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs and Senior Curator of Ancient Art at the Walters Art Museum, has noted about the work, “On the one hand, the mirrors are an equalizer—by reflecting the viewer’s own image, the mirrors pull them into Grant’s world. On the other hand, the mirrors also reflect the light outside the windows over Mount Vernon, which becomes a metaphor for the freedom Grant was unable to experience.”

As the century moves forward, the Walters Art Museum remains dedicated to adding both historical and contemporary works that enhance and expand the stories we tell, help make our collections relevant to our visitors, and capture the impressive artistic achievements of our diverse population and their ancestors. These efforts include plans for new art activations by living artists in the museum’s existing galleries and collection-based shows, contemporary artworks integrated into our public spaces, and loan exhibitions that feature works by living artists. In combination, these efforts promise stimulating and transformative museum experiences for all as the Walters moves toward its centenary and beyond.

[1] William R. Johnston, William and Henry Walters: The Reticent Collectors (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999).

[2] Kristen Nassif, “The Business and Politics of William T. Walters’s Collection of American Art.”

[3] The Walters Art Museum Curatorial Strategy, curatorial files, 2020.

[4] The Walters Art Museum Curatorial Strategy, curatorial files, 2024.

[5] Our gratitude goes to Lynley Herbert and Earl Martin, whose work on the 2024 Walters Art Museum exhibition Reflect and Remix was the source for a number of the contemporary and historical comparisons noted in this essay.

[6] For discussions of Wiley and his work, see Deborah Solomon, “Kehinde Wiley Puts a Classical Spin on His Contemporary Subjects,” The New York Times, January 28, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/01/arts/design/kehinde-wiley-puts-a-classical-spin-on-his-contemporary-subjects.html; Claudia Schmuckli, ed., Kehinde Wiley: An Archaeology of Silence (DelMonico Books/Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2023); Emma Naroumbo Armaing, “L’artiste Kehinde Wiley convoque les visages du monde entier à Cannes,” Numéro Art (July 2020), https://numero.com/art/numero-art/lartiste-kehinde-wiley-convoque-les-visages-du-monde-entier-a-cannes/. We thank Christine Sciacca for her research on Wiley’s Saint Amelie, which has informed much of what we have written here.

[7] For a discussion of Lugo’s work, see Joyce Lovelace, “Agent of Change,” American Craft (April/May 2016), 44–51. More information about Roberto Lugo and his work is available on the artist’s website, https://www.robertolugostudio.com/press, which includes reviews that discuss his background and work. Thanks to Earl Martin for his research on Roberto Lugo’s Slave Ship Potpourri Boat, which we have drawn from here.

[8] See the data from the 2010 and 2020 United States Census Bureau reports for Baltimore City: https://planning.maryland.gov/MSDC/Documents/Census/Cen2010/sf1/sumyprof/profile/county/Baci.pdf; https://data.census.gov/profile/Baltimore_city,_Maryland?g=050XX00US24510.

[9] The first World Forum for Food Sovereignty, held in Nyéléni Village, Sélingué, Mali, in 2007 defined Food Sovereignty as “the right of peoples to healthy, culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.” See https://www.fao.org/agroecology/database/detail/en/c/1253617/#:~:text=An%20group%20composed%20of%20Friends. The relations among the land, sacred food knowledge, and the people who have long inhabited specific lands are a further concern that is of additional importance to Indigenous communities.

[10] Ellen Hoobler, “Revolutionary Love,” Bmore Art Magazine, July 12, 2023, https://bmoreart.com/2023/07/revolutionary-love-the-art-and-life-of-jessy-desantis.html. DeSantis’s webpage is a source for more information about the artist: https://www.jdesantisart.com/artist. Ellen Hoobler’s work on De Santis’s Cintli, Corn, Maíz has informed much of what we have written here.

[11] Jonathan Bloom and Sheila Blair, Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture (Oxford University Press, 2009), 348; M. Uğur Derman, Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from Sakıp Sabancı Collection, Istanbul (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), 46; Mohamed Zakariya, “Becoming a Calligrapher: Memoirs of an American Student of Calligraphy,” in M. Uğur Derman Sixty-Fifth Birthday Festschrift, ed. Irvin Cemil Schick (Sabanci University, 2000), 66–68. Thanks to Ashley Dimmig for her research on Mohamed Zakariya and his work; it has informed much of what I have written here.

[12] Eleanor Heartney, Anil Revri: Into the Light (Project Space, American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center, 2021). James W. Mahoney, “Anil Revri’s Transmodern Singularities,” 2004, https://www.anilrevri.com/essays/james-mahoney.

[13] Satoko Fujikasa, “Spinning Air from Clay: The Ceramic Art of Satoko Fujikasa,” artist’s lecture, Portland Art Museum, September 17, 2015, posted September 23, 2015, by Portland Art Museum, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i6_kCaPq84Q. Joe Earle, Radical Clay: Contemporary Women Artists from Japan (The Art Institute of Chicago, 2023). Also see Joan B Mirviss’s website for a biography of the artist, https://www.mirviss.com/artists/fujikasa-satoko.

[14] For more on Herbert Massie and his work in Baltimore, see Laura Melamed, “Self-Taught Artist’s Commission,” Beacon, December 18, 2023, https://www.thebeaconnewspapers.com/self-taught-artists-commission/. Thanks to Gina Borromeo for her work on Herbert Massie that has informed this content. A copy of a letter written by Sybby Grant is also in the collection of the Walters Art Museum, https://art.thewalters.org/detail/97304/autograph-letter-from-sybby-grant-to-her-master-john-hanson-thomas/.