Cabinet containing lab equipment and commercial products used in the first decades of conservation and technical research at the Walters

In 2024 the Walters Art Museum marked two significant milestones: ninety years as a public institution and ninety years since the establishment of the Department of Conservation and Technical Research. The department was the third to be established in the United States behind the Fogg Museum at Harvard University and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. In its over ninety years of existence, there have been many pivotal moments and eras, as well as many tools and materials representing the passage of time. These have been preserved in a cabinet at the entrance to the Conservation and Technical Research labs (fig. 1). The full history of the department with the contributions of each of its staff is well outside the scope of this essay and will be for others to capture as the labs move into their next century. In this essay, I aim to relate the early genesis of the labs as part of the formation of the museum and trace the story through pivotal moments that gave shape to the roles that conservation and technical research play in the museum today.

Henry Walters and Caring for His Collection

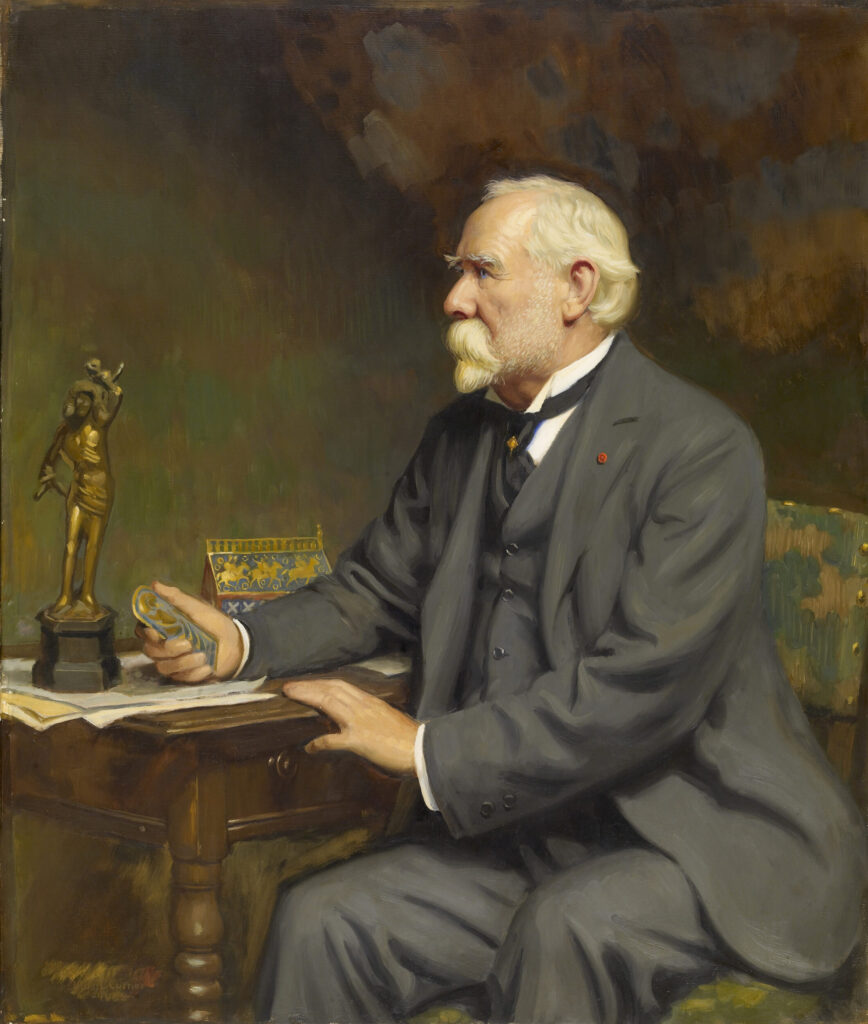

Posthumous portrait of Henry Walters with enamel and metal objects from his collection

Thomas Cromwell Corner (American, 1865‒1938), Portrait of Henry Walters, 1938, oil on canvas, 45 11/16 × 38 9/16 in. (116 × 98 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Commissioned from the artist, 1938, acc. no. 37.1682

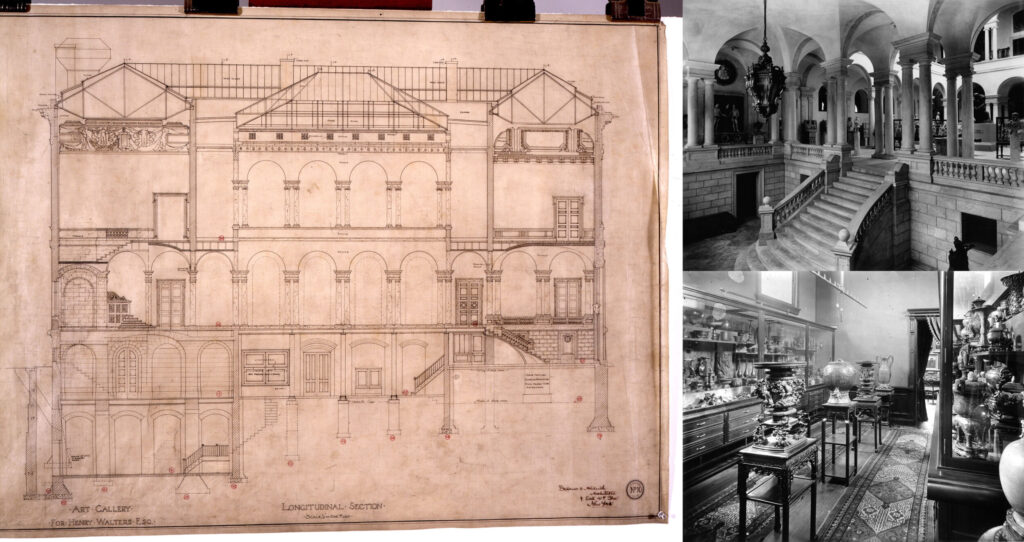

The story of the commitment to care and study of the Walters’ culturally and materially diverse collections begins well before the institution was founded. Though founder Henry Walters (1848–1931) resided in New York City rather than his home in Baltimore during the later phases of his collecting life, he remained connected to and invested in his collection, and that of his father, William Thompson Walters (1819–1894), in Baltimore through trusted acquaintances and consultants (fig. 2). After William’s death in 1894, Henry made plans for a palazzo-style building to house and display his family’s collection (fig. 3). The collection had outgrown the family home at Five West Mount Vernon Place in Baltimore, where it had been on display and periodically opened to guests who were fortunate enough to have secured an invitation. From the start, Henry actively engaged in the care and preservation of the family’s collection.

Architectural drawing of the Palazzo (Charles Street building) by Delano and Aldrich Architects for Henry Walters, 1906 (left); completed interior Sculpture Court of the Palazzo building (top right); gallery bridging the Walters home at Five West Mount Vernon Place and the Palazzo building (bottom right)

From his New York City residence, Henry Walters assembled a team of trusted employees and partners to carry out his wishes and plans for the collection, which would be housed in a new building designed by prominent architect William Adams Delano and modeled on its interior after a seventeenth-century palazzo (palace) in Genoa, Italy. One of Walters’s earliest and most steadfast employees was James C. Anderson (1871–1941). Anderson was an engineer by training who worked as superintendent of the Walters family collections and the buildings they were housed in from 1908 to 1932.[1] This included the Walters family residence at Five West Mount Vernon Place and the Delano-designed Palazzo building, which opened to the public on February 3, 1909. The Walters Art Museum Archives contains a set of two volumes referred to as the Anderson Journals, which are an accounting of information related to activities in the Walters Art Gallery from 1908 to 1932. Anderson recorded such detailed information related to the arrival of crates of objects or to the cost of electricity, which he would relay to Walters on a regular basis.[2]

In his role, Anderson oversaw the earliest recorded work on the care of the collection as directed by Henry Walters. Throughout the first two decades of the twentieth century, Walters engaged two paintings restorers, George Bruce and Stephen Pichetto, to attend to the needs of his Baltimore collection.

In a letter dated January 20, 1909, with a typed signature line “Supt,” which is here interpreted as superintendent, and therefore assumed to be from Anderson, he writes to a Mr. Geo (George) Bruce of Homestead, New Jersey, acknowledging the receipt of a box sent back to the Walters containing the two pictures that “you fixed;” it goes on to say that “I have hung them, and they look fine.”[3] A letter from the week prior from Bruce to a Mr. F. J. Banks in Baltimore has a letterhead that identifies Bruce as a “Picture Restorer” from New Durham, Hudson County, New Jersey.[4]

By the early 1920s Henry Walters had employed Stephen Pichetto. The Walters’ archives contain letterhead from Pichetto which reads: STEPHEN S. PICHETTO, Expert Restorer of Antique Paintings, 730 5th Avenue, New York. At this time, Pichetto’s services were also used by the collector and chain store magnate Samuel H. Kress.[5] The use of the same restorer undoubtedly demonstrates Henry’s close connections and interactions with other early twentieth-century collectors.

A series of correspondence between Anderson and Walters in the early 1920s captured the flavor of their working relationship and the details related to care of the collection that Walters left in Anderson’s hands.

“Dear Sir: As I explained to you, I have arranged with Mr. Pichetto to spend about two weeks in Baltimore during May, June and July, probably alternating the weeks. During May he will work on the pictures in the Galleries because the canvases will not be put on until June the 1st, which I have arranged through John Walsh * During June and July he will take the picture out of the Galleries down in the long storeroom along Centre Street, just as Bruce used to do. Yours very truly, signed HWalters.”[6]

Again, on May 22, 1925, Walters writes to Anderson that he has engaged Pichetto “who will begin work at the Gallery at once and work as usual through the Summer and Fall. . . . Please make a list of each picture that he works upon each month, so that I can gather some idea as to what work he is accomplishing. You need not say anything to him about this.” Through this short correspondence, Henry seems to indicate that he has reason to check on Pichetto’s progress, and letters back and forth to Anderson and Pichetto document multiple delays in accomplishing the work.

The working arrangement between Walters and Pichetto lasted through Henry’s lifetime and was still in place while the gallery was undergoing a refurbishment in the spring of 1931. It was routine for Pichetto to bring a group with him to work on the pictures in the Walters collection. In a letter dated May 19, 1931, to Anderson, Pichetto wrote: “Now that your Gallery is closed, I have made arrangements to come down the first week in June with about the same group I had with me on my last visit. In this way, I know I will have the satisfaction of leaving with the feeling of having a great deal accomplished.”[7]

Shortly before Henry’s death on November 16, 1931, Anderson writes: “My dear Mr. Pichetto: When you were last here, you promised to send me a material with which to wipe the bloom from the paintings, as I have not received the same up to the present time, I will appreciate it very much if you will send it or let me know what it is and where I can get it. Hoping you and yours are well, and to see you before the opening of the Gallery, I remain Sincerely yours, Supt.”[8]

In addition to Anderson, C. Morgan Marshall (1881–1945), an engineer by training, served as consultant to Walters for thirty years, beginning in the first decade of the twentieth century. Upon the death of Henry Walters and the formation of the Board, Marshall was appointed Administrator and Head of the Board and eventually acting director of the fledgling museum.

The impact of this long-standing working relationship was distilled in an excerpt from the Journal of the Walters Art Gallery in 1945, the year Marshall passed away: “This long contact resulted in an invaluable acquaintance with the history and content of the collections and comprehension of their significance, combined with a unique understanding of the technical problems of safe-guarding, installing and exhibiting objects of art. It was natural that the latter interest led to his enthusiastic promotion of a laboratory dedicated to the scientific examination of art works and their preservation.”[9] Marshall clearly understood and internalized Henry’s concern for the care of his collection and was a pivotal voice of support in establishing a conservation lab at the Walters.[10]

Working in tandem, Marshall, acting director, and Anderson, building superintendent, were both hand-selected by Henry Walters during his lifetime and had the explicit authorization and responsibility for oversight of the buildings and care of the collections. Their affiliation with the Walters as a museum would continue through both of their respective lifetimes.

A third confidant, William H. Francis (ca. 1835–1931), played an important role in caring for the Walters collection. Francis was born in Baltimore, Maryland, about 1835, and from 1877 until the time of his death in 1931, acted as the first steward of the Walters family’s growing art collection.[11] Francis, an African American, was first hired by Henry’s father, William, for whom he spent most of his working hours guarding the art stored at the family home at Five West Mount Vernon Place.[12]

His role appears to have been multifaceted, as a friend and confidant to the senior Walters as well as a trusted guardian and steward of his collection. Francis was described as “a quick and serious study, and it was not long before he knew every painting in the collection and could act as a guide through the private gallery.”[13] Francis was at William’s bedside when he passed in 1894, and Henry continued to employ Francis, including after the opening of the new building in 1909. Henry also maintained the tradition started by his father in 1874 of opening up the collection to the public a few months each year to benefit the Baltimore Association for the Improvement of the Condition of the Poor. Francis was a fixture in the place and a familiar figure to those who visited.

Francis passed away a month after Henry Walters. Shortly after his death on December 16, 1931, William H. Francis was memorialized as the man who “spent 52 years as Friend, Confidant and Guardian of Art Collector.”[14] At the settling of Walters’s estate, Francis’s widow received the funds left for him, in the amount of $25,000, a sizable sum in 1931. As Walters’s will was quite brief, only two pages long, and the majority of his holdings went to the citizens of Baltimore, the sum left to Francis was a clear acknowledgement of the importance of this man in Walters’s life and for the collection. He and Anderson, who also often stayed at the family’s house, were indeed the first caretakers of the collection.

While Walters relied on his dedicated team in Baltimore for day-to-day oversight, he demonstrated a keen eye for conservation concerns and an understanding of the impact environmental factors had on his collection. This was especially true for works of art that had recently arrived in Baltimore and were exposed to humid summers and the dry conditions caused by indoor heating during winter; this was in contrast to the primarily damp and uncontrolled conditions in palaces and churches across the globe where many of these collections originated. Prior to the availability of any “modern” method of cooling the historic palazzo building, “Walters used strips of canvas mounted on large rollers to cover the skylights in the summers when the building was closed. He had also introduced a dehumidifier that could be activated when a mechanism sounded a large horn loud enough to be heard throughout the building.”[15]

Henry also relied upon a network of colleagues within the tight-knit museum community of the Northeastern United States in the early twentieth century and frequently reached out to colleagues with questions about his collection. One subject in which Henry took particular interest was the problem of active corrosion among archaeological bronzes. While much of the corrosion formed during burial often obscured decorative details on ancient bronze surfaces, it was stable and did not progress over time in a museum setting. However, there was one type of corrosion, related to residual chlorides from saline burial environments, which could continue to attack bronzes once in the museum. This corrosion is exacerbated with changes in relative humidity in museums, and it affected many of the archaeological bronzes in the Walters collection. When Henry became aware of changes in appearance to some of his early bronzes, he wrote to Edward Robinson, then Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. On December 8, 1910, Henry wrote about “corroding cankers” that were beginning to appear on the bronzes.[16] These were bright green voluminous crater-like areas of corrosion that today are recognized as “bronze disease,” an aggressive form of corrosion that affects archaeological metals exposed to chloride salts.[17]Henry used potassium hydroxide bars in the glass cases with ancient bronzes to try to prevent and control bronze disease. This was likely a suggestion from Robinson. Additionally, Walters made reference to Egyptian bronzes having been through the hands of Alfred André, a well-known nineteenth-century French restorer,[18] and that he is therefore surprised that they are still corroding. This demonstrates that he was aware of problems preserving ancient bronzes and that there were restorers who treated them.[19]

Terry Drayman-Weisser, Director of Conservation and Technical Research at the Walters from 1977 to 2015 and now Emeritus Director, recognized that Henry Walters was one of “America’s foremost collectors of ancient bronzes, and he demonstrated deep concern for their preservation.”[20]

The Making of a Public Museum and Establishing a Department of Conservation

When Henry Walters died in 1931, both the New York and Baltimore cultural spheres were surprised to learn that he bequeathed to the mayor and city council of Baltimore, “for the benefit of the public,” the gallery, its contents, and the adjoining house at Five West Mount Vernon Place. On June 16, 1933, Baltimore Mayor Howard Jackson “vested control of the Walters Art Gallery in the trustees.”[21]

Quickly thereafter the city assembled a board of trustees to oversee the transition to a public institution. The trustees established an advisory committee composed of some of the most notable names in American museums at the time: Francis Henry Taylor, Director of the Worcester Art Museum; Henri Gabriel Marceau, Director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; Belle da Costa Greene, Director of the Pierpont Morgan Library; and Tenney Frank, a scholar of ancient history at Johns Hopkins University.[22] At the same time the trustees appointed Walters’s trusted confidant C. Morgan Marshall as “temporary conservator” and then “administrator” of the museum.[23]

One of the earliest references to the establishment of a technical research laboratory at the museum is found in notes from a meeting of the trustees on November 2, 1934, when Francis Henry Taylor presented a report from the assembled advisory committee, which had been in place for nine months. In his report he complimented the “Board on their judgment and vision in establishing a research laboratory” and he recommended that George L. Stout (1897–1978) be added to the advisory committee “with no salary obligations.”[24] Stout was head of the Research Laboratory at the Fogg Museum, Harvard University, the first museum conservation laboratory in the United States, and later would be known for his work during World War II as a member of the army unit dedicated to the recovery of art, familiarly known as the Monuments Men.

Taylor also reported “that an understanding had been affected with the Fogg Museum for close cooperation with the Walters Gallery in laboratory research work.” At this time, the Fogg Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston were the only institutions to have formal conservation labs in the United States.

Specifically, it was the Fogg Museum’s conservation department with its focus on the technical study of art that was key to the formation of the Walters’ department of conservation in 1934. At the Fogg, Stout as head of the Research Laboratory had hired Rutherford J. Gettens as the museum’s first chemist, and together with Edward Waldo Forbes, the Fogg Museum director from 1909 to 1944, they fostered a more scientific approach to the study of art.[25] With Stout on the Walters’ advisory committee, this scientific approach served as a model for the Walters. Stout found a receptive ear and like-minded colleague in Marshall: “Just as Forbes had wanted the Fogg to be the first museum in the US to have a chemist, mainly because the British Museum had one, so Marshall desired to have one at the Walters.”[26]

Domestic spaces from Walters family home transformed into chemical storage and working spaces

So it was that the Walters’ department of conservation, which would become iconic to the Walters and instrumental to the growth of a burgeoning field of study, was established at the date of the museum’s founding:

A laboratory for this work, which is being done in cooperation with Fogg Museum, Harvard University, has been established beyond the enclosed bridge between the museum building and the Walters residence at 5W Mt. Vernon Place [(fig. 4)], and part of this first floor of the dwelling has been made over into a studio for photographing the objects of art [(fig. 4, bottom right)], the ordinary processes for use in connection with the catalog [the earliest staff was engaged with cataloging the entire collection], and the x-rays, infra-red, and ultra-violet rays in connection with the work of attribution and or reconditioning and restoration. The laboratory is being equipped gradually, as the work progresses.[27]

In preparation for the opening of the newly formed institution, storage bins and racks were put into place for art storage, modern lighting was installed, and a system of air conditioning to combat the Baltimore heat and humidity was installed for the summer months. This work took place over a period of three months in the summer of 1934, leading up to the opening of the museum later that November. Prior to this the building was only open January through March.[28]

The Walters Art Museum, then known as the Walters Art Gallery, opened its doors for the first time as a public institution on November 3, 1934. The annual report of that year noted:

The city owes an obligation to Mr. Walters to see to it that the art collection given by him is kept at all times in the best possible condition and is safeguarded against deterioration from any cause. Many valuable paintings were in need of cleaning, and many objects in wood, bronze and ivory were in need of treatment to arrest the ravages of time, atmospheric conditions and other sources of destruction. . . . David Rosen, of New York, whose work in reconditioning and restoration of objects of art is well and favorably known throughout the country . . . was retained as a member of the Walters’ staff, and came to Baltimore to establish a laboratory, not only for the reconditioning and preservation of the Walters’ collection, but to begin researches in that field which, it is hoped, will eventually be of benefit to art collections everywhere.[29]

David Rosen, Technical Advisor, 1934–1954

To staff this newly established department, the advisory committee hired David Rosen (1880–1960) as Technical Advisor to work at the Gallery for six months of the year. Rosen, a native of Russia, was a practicing art restorer who studied sculpture and painting in Paris before coming to the United States in 1913. In addition to the Walters, Rosen worked with the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Worcester Art Museum, and he maintained a private practice in New York City.

Though today Rosen’s treatment approach is considered controversial, as it often resulted in the unintentional and non-reversible removal of original material, in his time Rosen acquired a reputation as an early proponent of the scientific study of works of art. His work would become known among the leaders in the museum field in the second quarter of the twentieth century. Rosen made a name for himself and the Walters by attending professional conferences as early as 1935, when he participated in the Art Materials Working Group at the American Association of Museums (AAM) conference. George Stout, technical advisor at the Fogg Museum, was president of AAM at the time and took the opportunity to advocate for the need for good documentation in the study of art. Stout formed a small committee composed of three museum directors and the top conservators, including Rosen, to recommend a method for examining and recording the condition of paintings.[30]

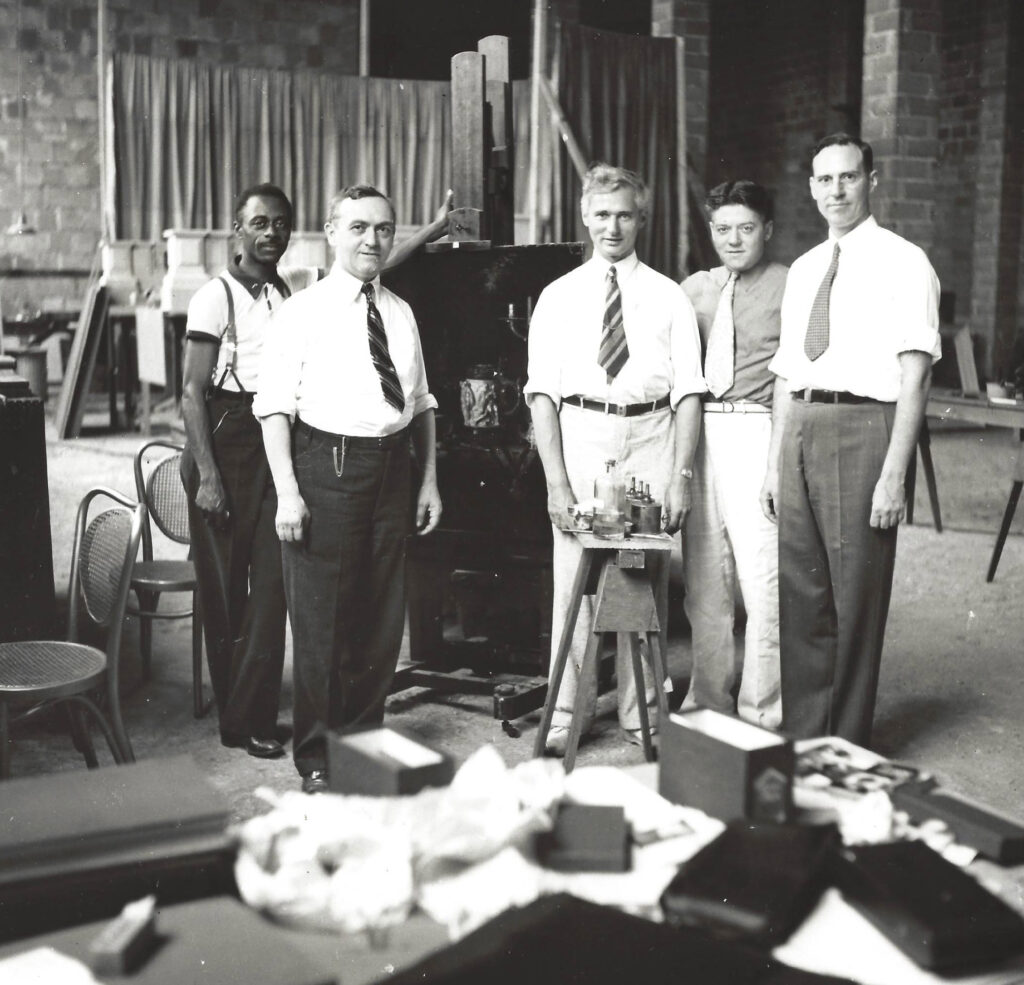

David Rosen, second from left, with Ernest Hunter, far left. Temporary Conservation space at the Philadelphia Museum of Art 1936. Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art

Throughout his career working at various institutions, Rosen trained many in the discipline of conservation. The first person Rosen trained was a young man named Ernest Hunter, who became acquainted with Rosen in the artistic circles of Greenwich Village, New York, in the 1930s. Hunter may have been the first African American conservator working in a US museum, and for a field that still has much work to do to be more inclusive of a diverse workforce, his story is notable in the history of conservation in the United States. During the Depression, before working in restoration, Hunter collected the work of local artists, many of whom he knew personally, as a means to help support them.[31] Hunter traveled with Rosen wherever he worked, to the Walters, the Philadelphia Museum, and the Worcester Art Museum (fig. 5). Unfortunately, there is little in the official museum record regarding Hunter’s work, but he was described as indispensable to Rosen, and he taught the future head of conservation at the Walters Elisabeth Packard “many tricks of the trade.” After Rosen’s death in 1960, Packard kept in touch with Hunter. He lived in Glen Cove, Long Island, where he was employed as an art restorer for the Pall Corporation, and continued work on large restoration projects into the 1970s. Packard described Hunter as “very skillful with his hands and very helpful to Mr. Rosen in lining paintings, consolidating panel paintings, [and] removing overpainting manually with a scalpel.”[32]

Harold D. Ellsworth, Chemist, 1934‒1937

In order to implement a more scientific approach to the study of art, Rosen brought chemist and physicist Harold D. Ellsworth (dates unknown) on board. Ellsworth was from Vermont and had a degree in chemistry from Middlebury College, completed graduate studies at Harvard, and taught for a period at Tufts Medical School. There was no single academic pathway for scientists interested in cultural heritage, as remains the case today, but Ellsworth was well connected and knew Rutherford Gettens (chemist and pioneering conservation scientist at the Fogg Museum) and Arthur Kopp, who would become the technical expert at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ellsworth stayed at the Walters for just over three years, leaving in 1937 to work independently as a technical art expert.[33]

While working as a chemist at Harvard, Ellsworth collaborated with major names in the field of technical art history and study, including Stout and Gettens. He brought to the Walters a knowledge of the use of x-ray, infrared, and ultraviolet rays for the study of art. In 1934 Ellsworth drafted recommendations for photography, methods, and equipment. In a seventeen-page document, Ellsworth wrote, “The individual museum should however be equipped to carry on technical studies which might be called control work, which will enable it to properly care for its collections. And by the observations made increase the fund of knowledge concerning works of art and the best means of caring for them. Most of this work can be done by x-ray photography, infra-red, ultraviolet, photomicrography and testing and control of the materials and methods of restoration and preservation.”[34]

Ellsworth’s work was specifically highlighted in one of a series of Baltimore Sun articles leading up to the opening of the museum in November 1934. A week ahead of the opening, the following was published:

The careful eye of Harold Ellsworth, a technician whose experience as a chemist on the Harvard faculty are added years of art research, has employed X-ray, infra-red, and ultra-violet rays as they never before were employed in Baltimore to detect faulty work—and prove the genuine work as well—in canvases that have been under suspicion as not wholly genuine. Quite unknown save to a very few, this research has been carried on with a battery of cameras and electrical equipment in what was once the paneled dining room of the Walters mansion adjoining the Gallery. The equipment has been of inestimable value in having this highly technical work performed almost on the spot, without the risk involved in moving precious works of art to distant laboratories in New York or Boston.[35]

In looking back at the coverage of the Walters’ opening, it is remarkable that the technical study and treatment of the collection was deemed of public interest from the start of this museum.

Elisabeth Packard: From Apprentice to First Female Head of the Department of Conservation and Technical Research, 1959‒1977

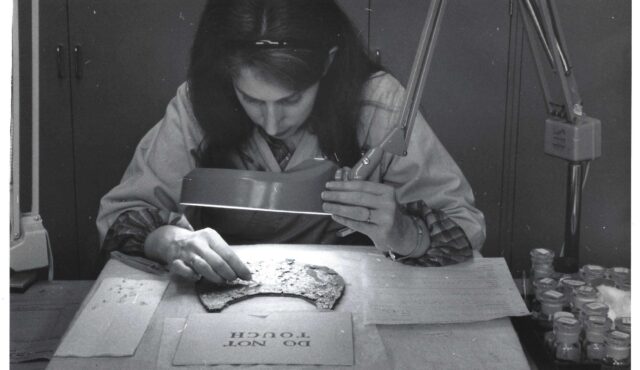

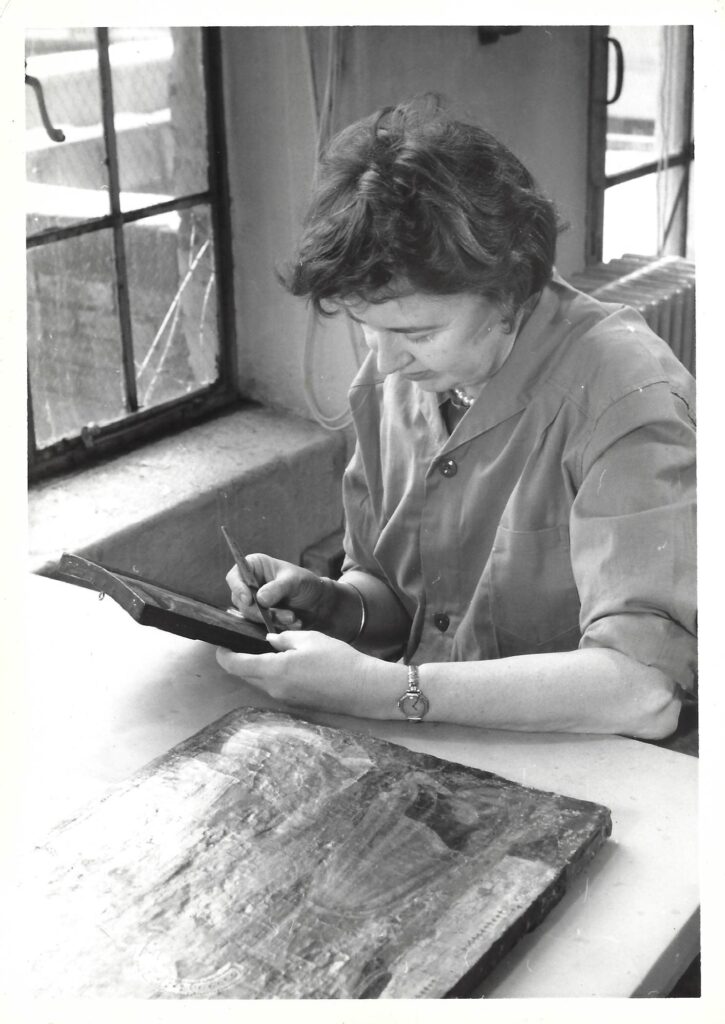

Elisabeth C. G. Packard (1907–1994) joined the Walters staff in 1934 and would stay at the Walters for more than forty years, taking her place as the first female head of the Department of Conservation and Technical Research in 1959 and remaining in that role until her retirement in 1977 (fig. 6).[36]

Elisabeth Packard at work in the conservation labs at the Walters

Packard, born in Baltimore, was the daughter of an Episcopal minister. She graduated from both the Bryn Mawr School in Baltimore and Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania in 1928. She attended graduate school at Johns Hopkins studying archaeology and joined the Walters staff initially to help catalog the tens of thousands of objects left in crates and boxes upon Walters’s death. From the beginning, Packard forged her own path, and when Rosen was hired as a conservator consultant for the Walters, Packard asked if she could become his apprentice. In her words: “I was interested in the field and asked him if I could join the department . . . and he took me on and I’ve been here ever since.”[37]

It is noteworthy that from the beginning, Packard was involved in the emerging field of conservation at the national level, and her career parallels the growing professionalization of conservation. She participated in newly established Art Technical Sections (ATS) at annually convened AAM meetings, which represented one of the first forums in the United States for discussions between art historians and conservators. While this newly established group may have been at odds with the art historians of their time, Packard felt that there was little challenge in communication and understanding between the groups, mostly due to the distinguished leadership of Forbes, an art historian and director of the Fogg Museum, where technical study of art was already well established.[38]

Though primarily trained as a paintings conservator under David Rosen and Ernest Hunter, Packard was a keen observer and recorder of detail. She established a network of colleagues to tackle some of the most complex issues in early museum conservation. In one instance, Packard maintained a decades-long correspondence with Gettens, then Technical Advisor at the Freer Gallery of Art, to consult on projects and conservation challenges well into the 1970s, when Packard retired.

Participation in an Emerging Field (Rosen, Ellsworth, Packard)

In the 1930s the conservation profession was still in its infancy. At the 1930 AAM conference in Rome, the term conservation was first recorded, likely replacing and distancing it from the restoration practice of the previous century.[39] The 1930s was also a burgeoning moment for the field of technical study of art, and the Walters’ establishment of a lab with a scientist at that time put it at the center of pioneering work. While attending these meetings, Packard observed a shift in focus from the 1934 meeting, where there was attention given to materials that living artists used, to 1935, where there was more of a focus on technical research on materials and techniques of historic works. This is reflected in a change in name of the session from “Art Technique” to “Art Technical Session.”[40] One of the speakers for this pivotal session was Ellsworth, the recently appointed Chemist at the Walters Art Gallery, who spoke on “Some Optical Methods of Examination.”

The Art Technical Sessions of AAM, 1936 in New York and 1938 in Philadelphia, included lectures by Walters Conservation staff Rosen and Ellsworth on topics that would become trademarks of early Walters research including: “The Ideal Results Sought in the Restoration of Ancient Bronzes,” “Case History of the Examination and Restoration of an Italian Painting,” and “Infrared Photography: Its Uses and Limitations.” Even Marshall participated and delivered a lecture to the assembled group, “The Laboratory from the Viewpoint of the Museum Executive.”

After Ellsworth left the museum in 1937, Packard was promoted to Assistant to the Technical Advisor, a title Ellsworth previously held. As Rosen only worked at the museum part-time, it was Packard who continued the work conserving and studying the collection year-round. Her eagerness and dedication to learning from Rosen and other mentors in the field, and her exemplary work maintaining treatment records of everything that came through the lab, poised her to succeed Rosen and become department chair in 1959.

Throughout her career Packard supported the growth of the conservation profession. She served many roles in national organizations, including chair of the American Group (1961‒62) of the International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (IIC-AG), a predecessor of today’s singular national conservation professional organization in the United States, the American Institute for Conservation (AIC).

Pioneering Work in the First Decades

In a repurposed set of domestic spaces at the back of the original Walters home at Five West Mount Vernon Place, Rosen and team established a lab for conservation at the Walters. It included space for examination and treatment of paintings and sculpture and was adjacent to the museum’s photography studio at the time (fig. 7). The first major areas of concern for the collection, and therefore the work of the department, involved developing treatments for lifting paint on panel paintings, for worm-eaten wood, and for the rapid disfiguring corrosion that was bronze disease. In addition, the technical department took on the responsibility of routine care of the collection, including a careful watch over the condition of collections in storage and on view: “A regular schedule of inspection covers bronzes, textiles, tapestries, leatherwork, woodcarvings, and so on in order to detect any signs that treatment is needed. Twice yearly every painting on exhibition and once a year all paintings in storage are gone over and appropriate measures are taken to arrest any deterioration.”[41]

Jack Kirby at microscope and Elisabeth Packard working at easel in the lab; wax tank can be seen in back right corner (left); pair of unidentified conservators working in the lab spaces at the Walters (right)

Wood Panel Paintings

The Walters collection at this time consisted of approximately 2,500 paintings, almost a quarter of which were paintings on wood panel rather than on canvas. As collections moved from Europe, where they had acclimated to the cool, damp conditions found at palaces and churches year-round, to heated buildings in the United States, they were exposed to conditions that fluctuated between dry winters and humid summers. Objects made from wood, like panel paintings and polychrome sculpture, did not adapt well. The wooden substrate shrank and expanded with the seasonal changes in the relative humidity, causing painted surfaces to lift from the wood. Lab records in the 1930s and ’40s were filled with reports of “blister laying”—in other words, introducing some type of adhesive between areas of lifting paint and the wooden substrate to secure the paint. Changes in relative humidity also caused the initially flat plane of a panel painting to warp, often causing additional damage to the painted surfaces. Rosen believed that protecting the original wood with an isolating layer of wax would minimize the impact of changing moisture in the surrounding air. The issues with the structural treatment of panels is complex and was thoroughly reviewed in an article by Karen French.[42] Though this would not be an acceptable treatment today because it fundamentally alters the paint in a way that is not reversible, Rosen’s rationale in using this method was to avoid the more drastic measures taken by other labs, particularly in Europe, that involved effectively peeling the painted surface from the wooden substrate and applying it to a secondary stable support, such as a lightweight aluminum panel.[43] In addition to using wax to protect the wood panels from dimensional changes, Rosen again bucked a more invasive trend of applying a wooden cradle (fig. 8).[44]

Conservator removing wood cradle from reverse of panel painting

At this early phase and with the scarce availability of such expertise nationwide, the department consulted on and treated objects from other collections, both public and private. In 1935, Packard conducted what she considered her first experiments on a set of fourteenth-century panel paintings from Aragon belonging to a Mr. George Blumenthal in need of treatment for flaking paint.[45]

Sculpture and the Wax Tank

Elisabeth Packard and assistant lowering a panel painting into heated molten wax in the wax tank setup at the Walters

Three-dimensional wood sculpture suffered the same fate as panel paintings and additionally experienced structural damage from wood-tunneling insects, which often left the wood structure spongy and unstable. Rosen also ran early tests on how best to get wax to penetrate the deteriorated wood and demonstrated that fragile wood sculpture could be stabilized with the impregnation of wax, accomplished by immersing the sculpture and allowing molten wax to fill open pores and voids—thus, the wax tank was introduced at the Walters in 1937. The original tank measured three by six feet with a depth of twenty-six inches (fig. 9).[46]Sculptures were weighed before and after treatment to record the amount of wax absorbed into the sculpture. A Conservation Lab report, dated March 31, 1938, for the treatment of a large wooden statue of a seated Buddha from Tang dynasty China (619‒906 CE) in the Walters collection (acc. no. 25.9) provides details of the process (fig. 10). According to the record, the sculpture weighed 41 lbs. before immersion and 58 lbs. afterwards, a net change of 17 lbs. of added wax; the temperature of the wax was recorded at 72 degrees celsius. The lab report further explains that the lacquer Buddha was wrapped with absorbent cotton and muslin and then tied with string to prevent the lacquer from falling off. It was placed into the tank face down and then turned over after twenty-four hours. Once sculptures were removed from the tank, excess wax needed to be wiped off while still molten. The surface of the statue was said to be in “perfect condition when the cotton and muslin were removed,” though we know from lab records that the wax vat was often colored by flaking bits of polychrome during treatment.[47] The wax tank was in use at the Walters until 1970, and eventually made way for less invasive techniques, but in this early moment in the history of conservation, the wax tank was an innovative technique that multiple museum labs would subsequently install, and it saved many sculptures from ongoing deterioration. Sculptures treated with the wax tank remain free of pests and are stable as of the writing of this essay.

Before treatment, reverse showing flaking nature of lacquer on statue (left); detail of elbow after treatment in wax tank showing damaged but secured lacquer layers (center); front overall after treatment (right)

Buddha, China (Tang Dynasty), ca. 590, wood with lacquer and paint, 41 3/8 × 28 3/4 × 21 11/16 in. (105.1 × 73.1 × 55.1 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, 1920, acc. no. 25.9

Bronzes and the Electrolytic Technique

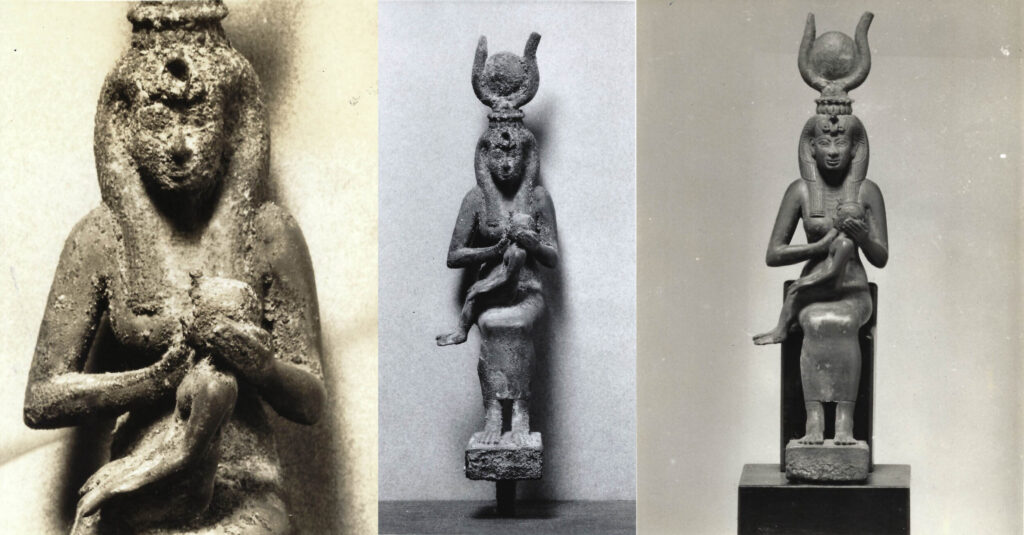

A key focus of the conservation lab was the removal of corrosion that obscured surface form and details on archaeological bronze sculpture. During his tenure at the Walters, Ellsworth investigated treatments for ancient bronzes. In 1936, he co-authored a paper with Gettens: “Examples of the Restoration of Corroded Bronzes.”[48] Part of this work included applying the most current scientific research on the treatment of bronzes, which had at its core the application of an electrical current under very specific conditions to remove burial corrosion from the surface of archaeological bronzes.[49]

Detail of corroded Egyptian bronze sculpture before and after electrolytic treatment

Isis Nursing Horus the Child, Egypt, mid-3rd‒mid-2nd century BCE, H: 7 13/16 in. (19.9 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, 1909, acc. no. 54.792

This method produced dramatic results in a short period of time with what was understood at the time to do little or no damage to the object (fig. 11).[50] He and other staff could not know that the treatment would have later ramifications that would be addressed by future conservators in the lab.[51]

Technical Studies: X-Radiography

With a restorer (Rosen) and chemist (Ellsworth) on staff, the early days at the Walters lab also focused on technical studies of the collections using microscopes, ultraviolet lights, and an x-ray apparatus.

Before treatment (left); after treatment and removal of later paint that was obscuring the portrait of child discovered through x-radiography (right)

Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci) (Italian, 1494‒1557), Portrait of Maria Salviati de’ Medici and Giulia de’ Medici, ca. 1539, oil on panel, 34 5/8 × 28 1/16 × 3/8 in. (88 × 71.3 × 1 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters with the Massarenti Collection, 1902, acc. no. 37.596

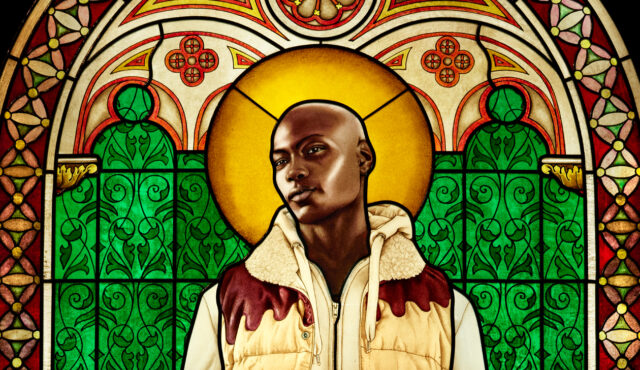

The introduction of x-radiography for the study of paintings represented a foundational shift in the work of conservation. It allowed conservators to see beneath the surface and to understand how layers of a painting were applied, as well as more concretely understand their condition in a completely non-invasive way. Soon after the establishment of the department, an x-ray system was set up in the technical labs at the Walters, one of only a few in US museums at the time. Early investigations using x-radiography focused on the paintings in the collection, sometimes revealing surprising discoveries that changed the art-historical interpretation of a painting. For example, in 1939 a portrait of Maria Salviati de’ Medici by Pontormo was x-rayed and revealed a figure of a child hidden by later restorers’ paint. Walters conservators subsequently removed this paint to reveal the child. Curators would later identify the child as Giulia de’ Medici, the mixed-race daughter of the deceased Duke Alessandro de’ Medici, who was of African ancestry (fig. 12).

Core Tenets of the Walters Department

In many ways the early decades of the new department maintained the legacy of Henry’s early concern with his collection. General stewardship of the collection continued to be top priority, with the conservation staff maintaining a regular inspection of collections to determine if any treatment was needed, and twice yearly every painting in the collection was examined for signs of deterioration and steps were taken to intervene.[52] These decades also laid the foundation for the core tenets of the department, which would come to define Conservation and Technical Research at the Walters today, including research, training, documentation, and outreach. From the establishment of the department, records were kept regarding treatment and the number of objects and paintings moving through the lab each year. The annual report from 1937 alone records 327 objects went through the lab, including paintings, bronzes, enamels, wood, ceramics, and metalwork; objects were entered into a record book and a “detailed account [was] made of the procedures and work done to each object.”[53] Given the early date of the lab at the Walters and the extensive records maintained over the duration of the department’s existence, the records constitute a valuable repository of the history of treatment of museum collections in the United States. Early logs, kept in faux-leather black binders, record objects and paintings coming in and out of the lab. In addition to tracking movement, written records of examination and treatment were added to paper files for each object or painting from the beginning. Preserved until this day, they provide insight into the earliest treatment priorities for the technical staff. While it seems that Rosen did not keep detailed records of his treatments at the Walters, notes from Packard in object files refer to treatments carried out.

Museum records also provide a window into early collaborations with external colleagues: “Work in the studio and laboratory is developing satisfactorily. . . . A very advantageous connection with the chemical faculty of the Johns Hopkins University has been effected . . . working with us on a problem of determining age and the cause of disintegration of ivory.”[54] The study of ivory and ivory materials would become one of the major areas of work in the objects laboratory under the future direction of Terry Drayman-Weisser beginning in the 1970s.

The Walters labs would also soon become a resource in the field to provide training to emerging professionals. In 1940, the lab welcomed its first trainee, a student from Goucher College in North Baltimore. This commitment to training burgeoned under Packard and then Drayman-Weisser’s leadership and would become one of the hallmarks of Conservation and Technical Research at the Walters, a distinction which continues to be a priority in 2025.

In this earliest phase of the museum, conservation was immediately part of the intrinsic fabric of the institution, consulted, respected, and promoted to the public through the media. It is in 1939 that we first see the name of the independent department of Conservation and Technical Research emerge, not under a curatorial or collections team, but as an autonomous department reporting to the museum’s director.

The conservation staff was aware of their own level of autonomy and of the trust the museum had in their work. They had a certain freedom, working closely with their curatorial colleagues, and this level of freedom in part appears to have created a crucible for great experimentation and learning that resulted in many contributions to the profession overall.[55]

The staff in the lab did not work in isolation but were rather a part of a network of scientists and restorers conducting technical studies, investigating objects in their collection, addressing complex treatment problems, and collaborating with curatorial colleagues.

Protecting a Collection in a Time of War

Along with other institutions in the United States and certainly in Europe, the Walters undertook an effort to safeguard the world’s cultural treasures from the potential imminent threat of enemy attack with the start of World War II. When the United States entered the war at the end of 1941, with the input of Rosen, then technical advisor, plans were laid out to protect the Walters’ collections. In 1942, the Walters executed a multitiered plan to safeguard the collections that included moving objects to areas within galleries deemed safe, placing paintings and manuscripts in the first floor vault within the museum, shifting easily monetized valuables to the Safe Deposit and Trust Company, removing the stained glass windows, and packing up collections destined to be moved off site for protection. After much consideration, Trustees selected the National Guard Armory in Frederick, Maryland, where hundreds of objects stored in over 125 galvanized iron cans would be housed for the duration of the war.

June 3, 1942, headlines in The Frederick Post included news of a world at war and a front page column that read “Art Objects to Be Stored Here for the Duration, Walters Gallery, Baltimore, Taking Steps to Preserve Valuable Pieces.”[56] After searching for a safe haven away from Baltimore, the gallery identified a below-cellar-level swimming pool at Frederick’s armory on Bentz Street. The then-small town of Frederick was located just an hour west of Baltimore and was clearly thought to have been a place at low risk of what many on the East Coast feared would be a targeted attack by enemy bombers.[57]

The article provides a surprising amount of publicly available detail about the preparations:

While in Frederick, the treasures of statuary and glass are to be additionally protected against fire of bombing by being enclosed in large, sealed cans and buried. Twenty-inch tall, galvanized iron containers of the type familiarly known in the Army as G.I. cans are to be used. Wrapped to prevent scratching, the busts, heads, statuettes, vases, bowls and other objects are to be placed in rock-wool inside the containers. The containers will then be placed in the concrete swimming pool of the armory, on a bed of sand. Sand is then to be packed around and on top of the cans to hold them stationary and to protect them from flames of falling timber in case of conflagration or bombing. The vault, which is being built over the cache, will not be proof against a direct heavy bomb hit, it is understood, but will be sufficient thickness to foil burglary, fire and indirect explosion.[58]

Though, rather ironically, a non-war-related fire did impact the side corridor of the armory in May 1945, it apparently sustained no damage. Later in 1945, the Walters’ priceless art was reclaimed from its underground slumber, and at the time damage as a result from the fire was noted on only two small Chinese porcelains.[59]

The story seems to be a bit more complex than this, as indicated on a conservation record from November of 1945 for a Greek, black-figured amphora (acc. no. 48.16). It states: “While stored during the war, dampness caused the disintegration of all the old repairs. Mold was brushed off.[60] The Amphora had to be built piece by piece, joined by Universal Cement. Cracks and missing areas filled with plaster and painted with shellac paint to harmonize with surrounding areas. Completed November 1945.”[61] Though the record does not explicitly mention the off-site storage location, the timing and the nature of the issues leads to the presumption that this vase was one of the collection pieces stored in the sub-cellar, likely damp, conditions of the Frederick armory’s swimming pool. Without a comprehensive list of objects stored off site, which has not yet been located, it is by chance that we may uncover additional treatments like this during the postwar years.[62]

Growing Impact Inside and Outside the Museum

Planning for a New Lab (1957–1966)

By the mid-1950s the gallery was bursting at the seams, in need of more space for the display and housing of its collection, and by 1959, then gallery director Edward S. King enlisted the services of local architects Wrenn, Lewis and Jencks on West Mulberry Street in Baltimore. From the outset King included Elisabeth Packard and conservation in his future planning exercise, and it was Packard’s role to make recommendations for space requirements for a Department of Conservation and Technical Research at the Walters. This must have come as a great relief to the staff, having worked from a makeshift series of labs at the back of the historic house on Mount Vernon Place since 1934.

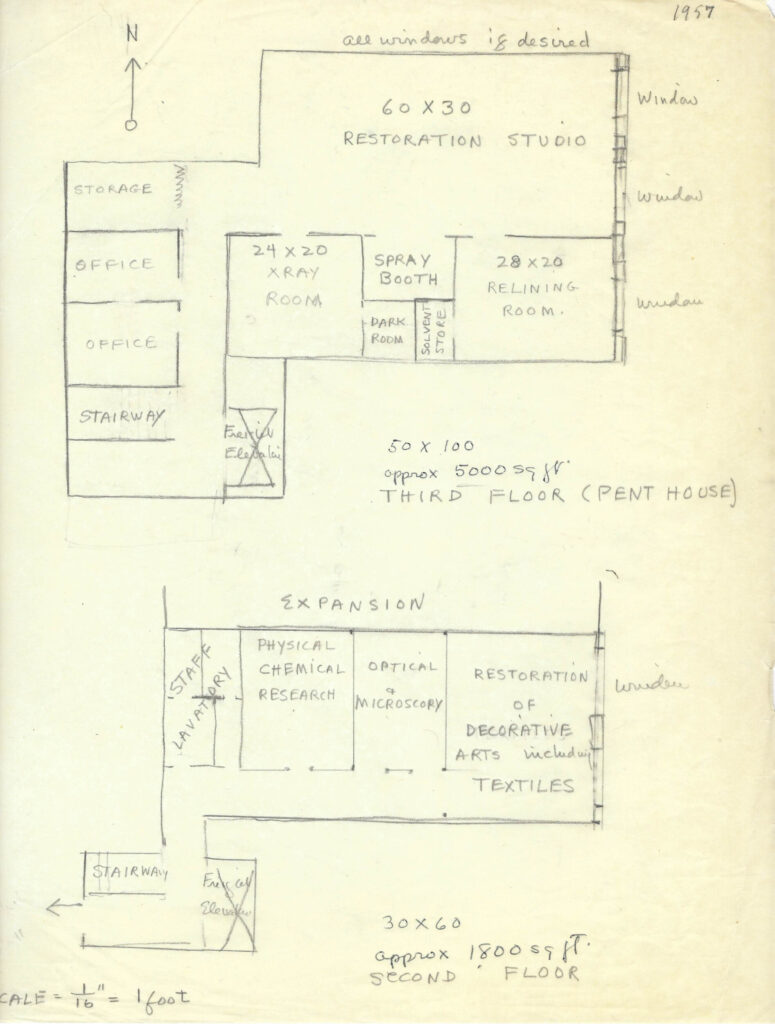

Her recommended specifications included over 6,000 square feet of space that included a restoration studio with high windows or skylights providing north light for color matching; an examination room for photography, x-radiography, and examination with ultraviolet and infrared light; a relining workshop with the wax tank, a hot table for lining paintings, and a carpenter’s bench; a workshop for repair of sculpture and decorative arts and washing of small textiles; and a physical and chemical research laboratory, technical library, office space, and receiving hall (fig. 13). In her document she was careful to include the need for exhaust fans and drains for washing sculpture. Her specifications would eventually lead to the new labs on the fourth floor of the Centre Street Building completed in 1974.[63]

Proposed lab upgrades in a hand-drawn diagram by Elisabeth Packard, 1957, Conservation Lab Archival Files

The fully integrated role of the conservation department at this time is also apparent, as Packard is included in strategic conversations about the overall direction and needs of the museum including a “Proposal of Committee on the Gallery for Future Direction of the Walters Art Gallery,” to which Packard added several notes for future discussion in the margins.

Publications, Exhibitions, Talks, and Tours

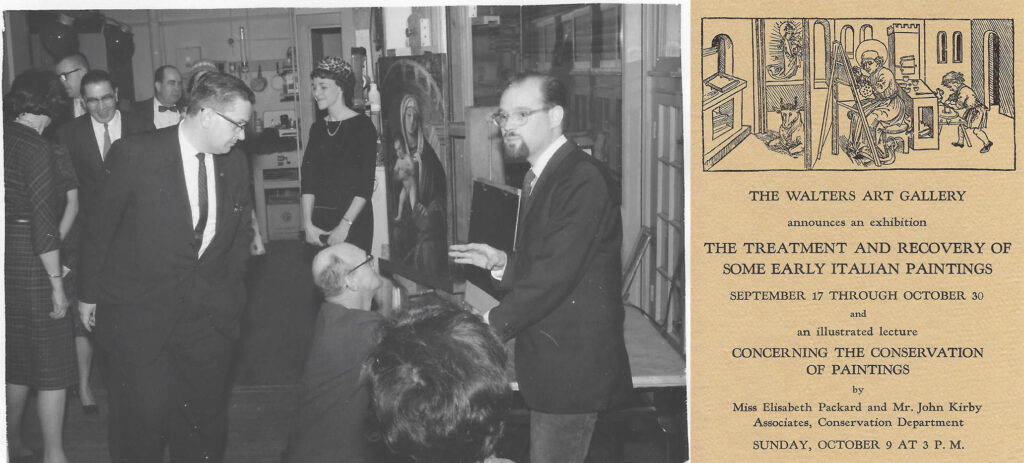

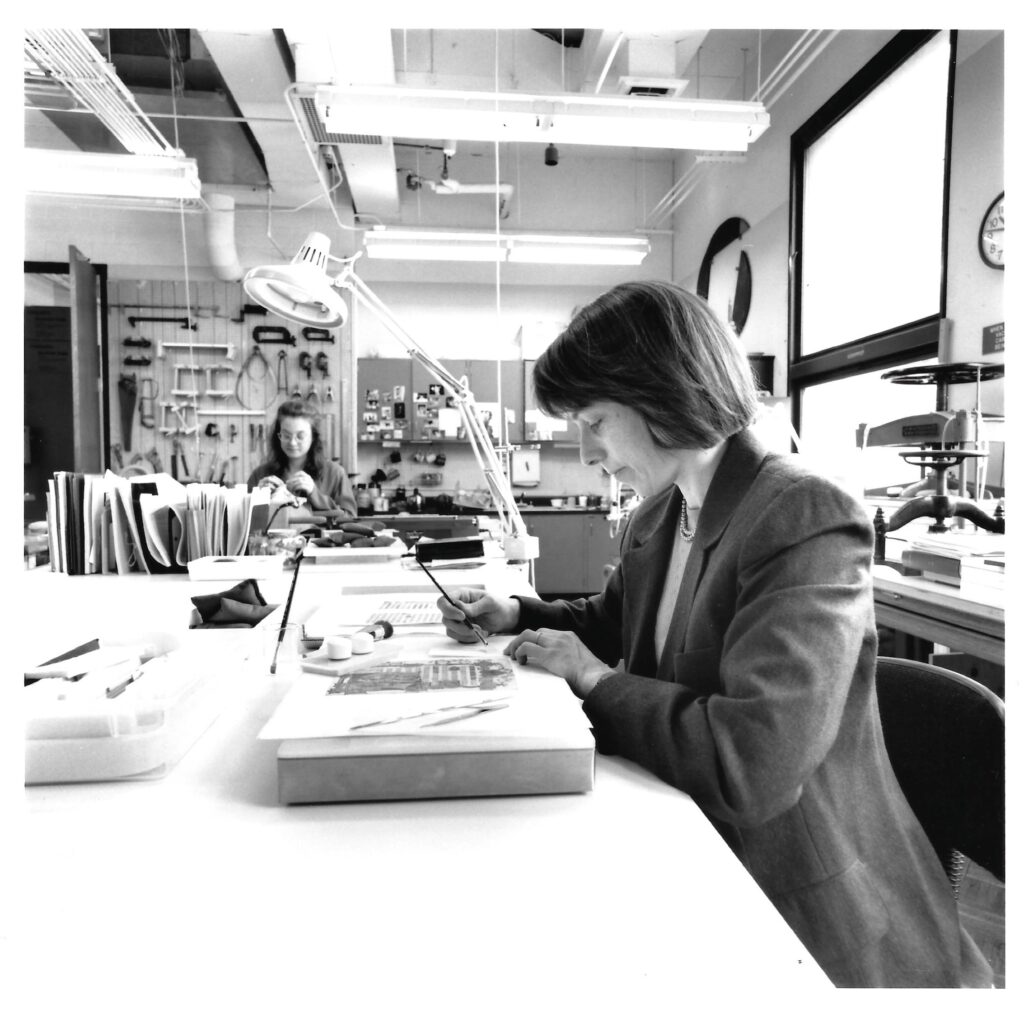

A distinctive feature of the Walters Department of Conservation and Technical Research was the extent to which its reach extended well beyond the confines of the labs. While too often conservation departments existed solely in service to a museum’s exhibition program, the Walters department was supported in its commitment to share knowledge and discoveries with museum constituents and the public. This was realized in multiple ways, through scholarly publications, exhibitions with conservation themes, talks to museum patrons, and opening up the conservation labs for visiting colleagues and potential donors (fig. 14, left).

With Packard leading the department, conservation at the Walters undertook one of its first comprehensive materials studies of a collection. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Kress Foundation supported the study of 150 works of art from the Italian paintings collection. The multiyear work focused on media and wood analysis of paintings and resulted in the publication of Italian Paintings in the Walters Art Gallery, Vol 1 by Federico Zeri with condition notes by Packard. Zeri, an art historian based in Rome, maintained a lengthy correspondence with Packard during the course of the project. In one letter, Zeri writes that “your unusual skill and understanding of the paintings have permitted in countless cases the critical and art historical judgment to go forward. Moreover, your technical notes are of the highest importance and quality. I am certain that in the future critical catalogues of public collections will follow the perfect example laid down by you.”[65]

Peter Michaels, Technical Assistant to Elisabeth Packard, talking with visitors at a lab open house (left); postcard from 1955 highlighting exhibitions and lectures by the conservation staff

Conservation staff regularly contributed to scholarship through publication in the Walters’ journal. In 1952–53 the Journal of the Walters Art Gallery published a Special Technical Issue, to which Rosen, Packard, and John (Jack) Carroll Kirby contributed. Kirby’s expansive article on the care of the collection compiled some of the earliest and most important work done in the first twenty years of the department’s history.[64]

Conservators also curated exhibitions, and many of those were paired with a series of lectures by conservators (fig. 14, right). Sometimes these were highlighted in the local Baltimore Sun; a Sun article from November 19, 1961, advertised a new Walters exhibition, The Technique of Fresco Painting. The exhibition ran for just one short month. Within this brief span of time, three lectures from the conservation team were offered to the public. Conservation’s level of involvement in programming, and the degree to which the museum found value in the contributions of the department, was quite remarkable. A series of exhibition offerings curated by the conservation team.[66]

The positive exposure both the museum and conservation labs received as a result of the public-facing projects did not come without the potential for criticism. Controversies over the cleaning of paintings, especially, have been part of art-historical discourse for centuries. Sometimes this is a result of the viewer reacting to the removal of layers of grime and discolored varnish, which reveals a more vibrant color palette still preserved beneath those obscuring layers, and sometimes it is in response to careless and ill-executed treatments.

Paolo Veronese (Italian, 1528‒1588), Portrait of Countess Livia da Porto Thiene and Her Daughter Deidamia, 1552, oil on canvas, 82 1/16 × 47 5/8 in. (208.4 × 121 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, 1921, acc. no. 37.541

Walters staff did not escape these controversies around the cleaning of paintings. In 1980 the Gallery put on an exhibition, Undercover Stories in Art, in which the conservation lab displayed paintings and sculpture alongside images of x-radiographs and ultraviolet- and infrared-light images that revealed aspects of the work not visible to the naked eye. This was the same year that the first phase of the work to clean the Sistine Chapel began, bringing the conversation about the cleaning of paintings into an international spotlight. One painting on view with an accompanying series of color images before and during cleaning was Veronese’s Portrait of Countess Livia da Porto Thiene and Her Daughter Deidamia. What ensued in the Baltimore Sun was a series of letters to the editor and responses from the museum regarding the appearance of the sixteenth-century Venetian painting by Veronese (fig. 15). A letter dated May 17, 1980, from a Mr. Melvin Miller declares, “the ‘Countess’ is dead.” The author assesses the sixteenth-century painting as a beautiful symphony, full of rich tones and brilliantly orchestrated, and he contends that the cleaners removed original green glazes from the daughter’s dress and caused loss of modulation in the faces.[67] A letter penned in response and signed by then head of conservation, Terry Drayman-Weisser, refuted the criticisms and explained and defended the professional standards and practices of the museum’s conservation staff.[68]

Impact on a Growing Field

The role conservation played at the Walters and that of its staff in the international field of conservation was reported on and of interest to Baltimore audiences by the 1960s. With Packard at the helm of the department in 1959, an emphasis was placed on contributions to the broader field of conservation. Staff members routinely presented research and treatments at annual conferences, situating the Walters in both a national and international spotlight. Packard led by example. She chaired the American Group for the IIC-AG, a predecessor of today’s AIC, an organization established to bring together conservators from around the world to share information, insights, and challenges within the conservation field.

The national stature of the Walters Department of Conservation and Technical Research was further solidified by Packard’s involvement, as departmental head, in developing two core documents for the field: the Code of Ethics and Standards for Practice, and guidelines for certification.[69] The original Code of Ethics and Standards for Practice, a document that outlines the guiding principles for all professional conservators and, while it continues to be revised, is still in use today.[70] She was involved in early discussions about the certification of conservators of art on paper.[71] The certification of all conservation professionals, inclusive of paper conservators, has never come to pass, even after multiple proposals over the years.[72]

Graduate programs for the training of conservators were established in the early 1970s, and the Walters conservation staff had strong connections to those fledgling programs. In addition to hosting internships at the Walters that provided those students with hands-on experience treating collections, Packard sat on the Advisory Committee for the Winterthur Program, the University of Delaware’s art conservation program,[73] and had long-standing connections with the founders of the graduate program in Cooperstown, New York, Sheldon and Caroline Keck.[74] In addition to serving as a sounding board for training programs as they established their curricula, Packard and other department staff also taught at many programs on topics including the wax immersion method of preserving polychromed wood sculpture, the transfer of paintings, deterioration of wood, and the radiography method.[75] Finally, as a result of the respect the department had garnered in the field, Packard was asked to serve as part of a committee gathered in 1977 to work on a proposal for a centralized US conservation center, then named Conservation Analytical Labs. This would eventually become the Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute.

The department under Packard was known for a high standard for ethical treatment and commitment to training, and through mentorship and sharing of information, paved the way for the careers of many conservators. The wide-ranging participation in professional activities well beyond the Walters lab at this foundational moment in the development of the field solidified the reputation of the Walters as a leader and contributor to the field.

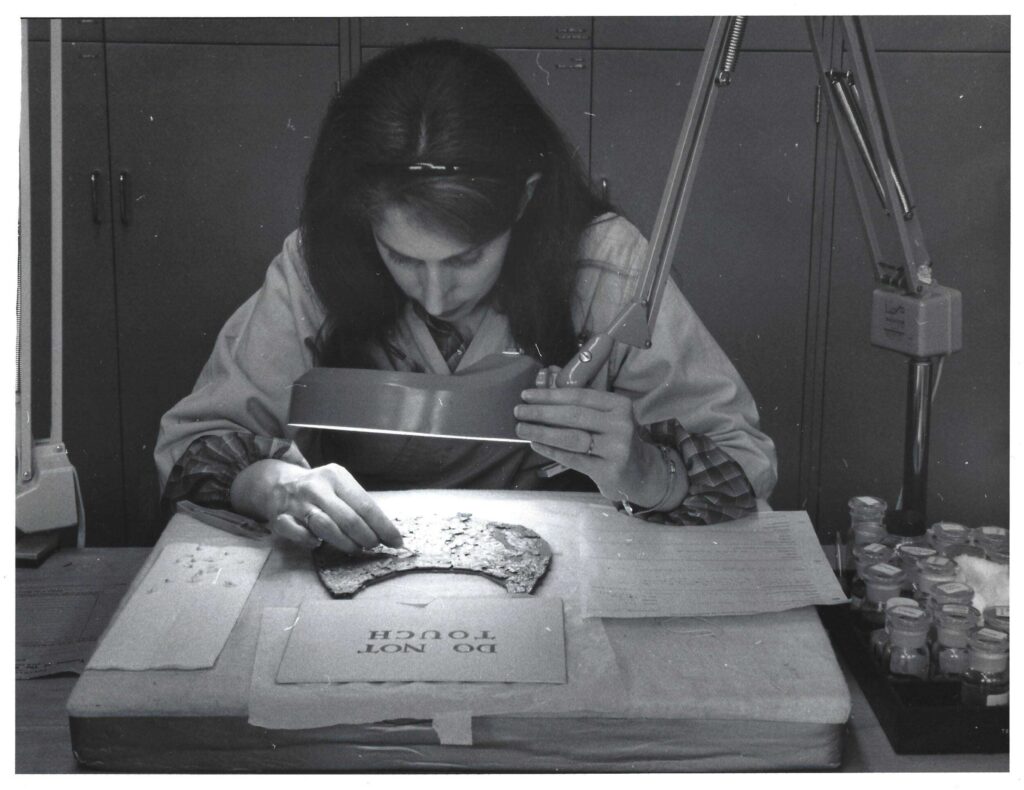

Terry Drayman-Weisser: An Objects Conservator Joins the Staff and Leads the Department into the Next Century

Elisabeth Packard considered Terry Drayman (now Drayman-Weisser) one of the most promising conservators of objects of the time. After a summer project arranged while she was still a student at Swarthmore College, Drayman-Weisser was asked to join the staff at the Walters conservation labs in 1969. Packard first trained Drayman-Weisser in the techniques of paintings conservation, but soon her particular interest in the conservation of antiquities became evident and corresponded well with the strength of the Walters collection. With a grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, Drayman-Weisser took a leave of absence from the museum to attend the University of London’s Institute of Archaeology. She graduated with distinction from its three-year intensive archaeological conservation training program. As part of her training, she participated in archaeological excavations in Nichoria, Greece, and Lincoln, England, which provided her with seminal experience and exposure to condition issues facing material culture from a burial environment. Each summer Drayman-Weisser would return to Baltimore to practice techniques she had learned, and after graduating from the Institute of Archaeology in London, she returned to the Walters in 1973 as the first ever program-trained objects conservator at the Walters (fig. 16).[76]

Terry Drayman-Weisser working on an archaeological gold pectoral (acc. no. 57.368), 1974.

Drayman-Weisser was a keen and curious observer. Her areas of interest and expertise would expand from archaeological bronzes to include fakes and forgeries, the identification of ivory materials and their treatment, and enamelwork throughout the collection. But her foundational experience and exposure to the archaeological conservation of objects by leaders in the field such as Tony Warner and Henry Hodges at the Institute of Archaeology made the Walters a center for the study of archaeological material from the 1970s. (See Appendix: Oral History with Terry Drayman-Weisser.)

Manuscripts

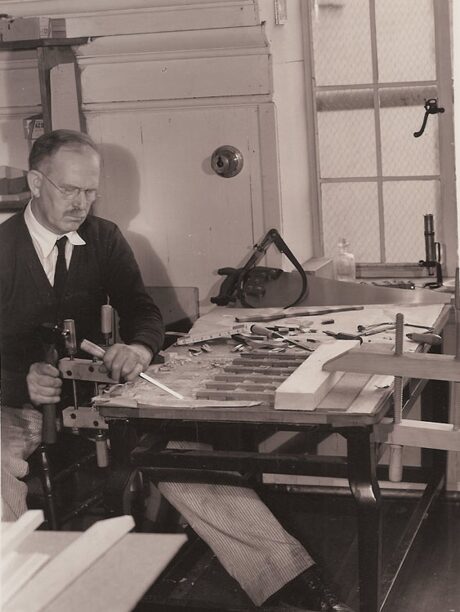

At this point in the department’s history there was yet one major area of the collection in need of assessment, treatment, and study—the Walters’ collection of rare books and manuscripts, which, within the United States, is second in scope and size to the Morgan Library in New York City. Until this point, staff paintings conservators, supervised until 1977 by Packard, treated flaking paint on manuscripts.[77] In 1977 the Walters received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities for the cataloging and condition reporting of the collection of western European manuscripts. Book specialist Chris Clarkson was hired to complete a detailed condition survey and technical description of each book, including measurements for appropriate book supports (fig. 17).[78] The timing of this important shift correlates with the hiring of the first Walters curator devoted to manuscripts and rare books, Lilian Randall, and the construction of a new building in 1974, which housed the research library and reading room.

Chris Clarkson demonstrates how to construct a book cradle for exhibition, 1977

Though conservation labs for paintings and objects were custom designed and included in the new 1974 building, Clarkson made the most of adapting the space that was left vacant when the lab spaces moved from the back of the Walters’ nineteenth-century rowhouse. Clarkson outfitted a small laboratory for the examination, treatment, and rehousing of manuscripts. Apparently needing total concentration for his work, in and among other museum offices and hallways, Clarkson had a hand-calligraphed sign reading: “Sorry, now working on manuscripts.”

Drayman-Weisser understood the importance of the Walters manuscript collection and of having a conservator to support that collection in particular, and she made a convincing case for the establishment of a new position in the department.

Changing Nature of Collections Care

Drayman-Weisser and her team were among the first to directly link collections damage to indoor pollutants. As museums modernized, they increasingly displayed objects within cases and introduced new materials in storage and display. It wasn’t until decades later that the impact of those changes became apparent. Some of the newly introduced materials emitted gases or pollutants that were slowly damaging collections. By the 1970s the conservation team at the Walters began to notice some unusual corrosion on metal surfaces. Often described in lab records as “brown fuzzies” and crystalline needles, these altered surfaces had formed on objects made from copper or silver and did not appear to be related to previous treatment. Initially it was thought that these “fuzzies” were a type of biological growth. Without a scientist on staff and with a lack of scientific resources available to the conservation field, the Walters reached out to Johns Hopkins Hospital labs to try to culture the material. With no success, museum staff then asked research departments at 3M and Martin Marietta to help solve the riddle and identify the mystery material.[79] Findings indicated a material high in sulfur. In the end, the problem stemmed from sulfur-producing rubber mats that had been installed on the floor of the main storeroom in 1934 to protect objects from damage if they fell. Drayman-Weisser shared these results at conferences and with colleagues.

Technical Studies Continue to Be a Hallmark

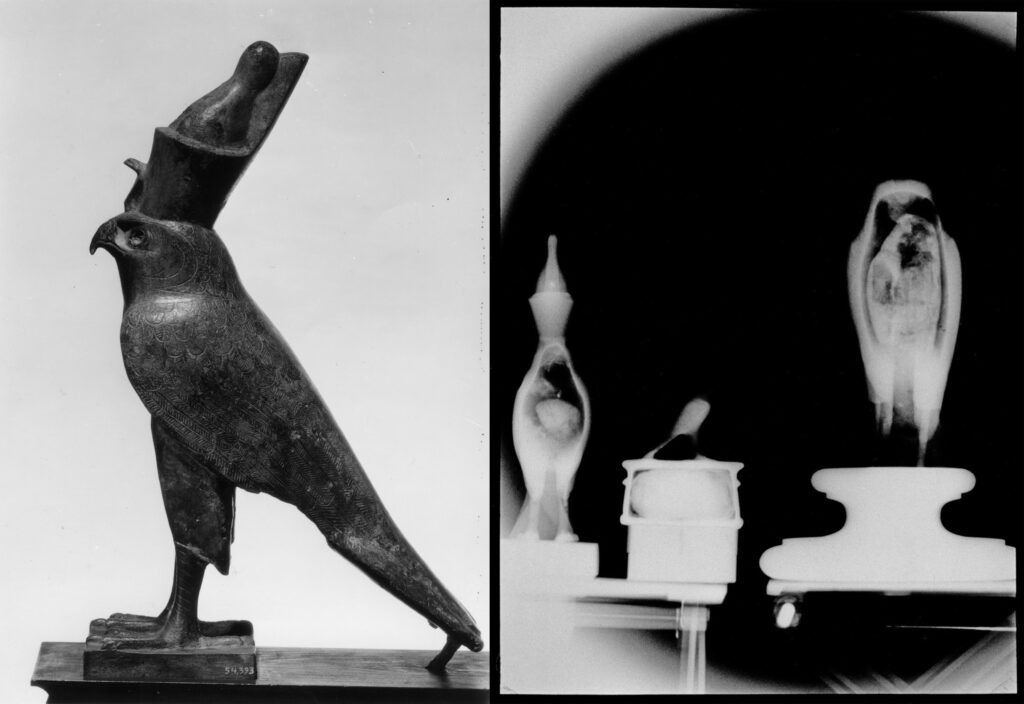

Neutron-induced radiograph of Horus Falcon, acc. no. 54.393, and other Walters Egyptian falcon figures showing mummified bundles within (right)

Horus Falcon, Egypt, mid-7th‒late 4th century BCE (Late Period), bronze, H: 15 1/4 in. (38.7 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, 1924, acc. no. 54.393

Even without a scientist on staff, technical studies by conservators in collaboration with the curatorial team to understand the materials within the Walters collection persisted in earnest on a small and large scale. Investigating the collection often revealed new discoveries. One such example was a project on the study of Egyptian bronze falcon figures in the Walters collection. Beginning with a simple observation during a routine examination of a bronze falcon figure, a small hole was noted at the top of the head, which revealed a hollow cavity below, eventually leading to the discovery of a bundle of small bones wrapped within textile (fig. 18).[80] Questions about this unusual feature led to a study of eight bronze falcon figures in the collection using the novel technique of neutron-induced radiography, an imaging technique that uses a neutron beam passed through objects and captured on neutron-sensitive film, in collaboration with staff at the nuclear reactor at the National Bureau of Standards in Washington, DC. The study confirmed that at least six, and likely eight, of the ten sculptures studied were hollow and contained mummified bundles of animals. These findings altered our understanding of Egyptian mummification practices and inspired practitioners in other museums to reexamine their collections. This level of curiosity and creative persistence in pursuing answers was a hallmark of Drayman-Weisser’s leadership of Conservation and Technical Research.

Ivory Sample Reference kits used for identification, teaching and training; Gift of Robert Mann

In the early years of the 1980s, object conservation was involved in two major systematic materials studies that were related to exhibitions and resulted in publications. Masterpieces of Ivory from the Walters Art Gallery included entries on some five hundred ivory objects in the Walters collection spanning millennia.[81] In preparation, the conservation team educated themselves on visual methods of identifying ivory from different animal species. Though “ivory” most commonly refers to the tusk of elephants, ivory can come from hippos and walruses, among other species. This work on ivory would propel the conservation team, especially Drayman-Weisser, into a long and distinguished commitment to the understanding, identification, and treatment of ivory from different species. The Walters’ specialty in ivory identification eventually led Drayman-Weisser to William R. (Bobby) Mann, the cofounder of the International Ivory Society (1996) and a collector of unusual ivories. Drayman-Weisser and Mann would go on to offer multiple hands-on ivory identification workshops for conservators and allied professionals. Mann bequeathed much of his teaching collection to the Walters Conservation and Technical Research Department, where it continues to be used for teaching and training (fig. 19).[82]The second systematic study resulted in Silver from Early Byzantium: The Kaper Koraon and Related Treasures.[83] The publicationwas much like Italian Paintings in the Walters Art Gallery, Vol 1, which provided detailed technical information on every painting; the silver publication included individual entries that detailed technical information on materials and methods of making as well as an essay summarizing the findings and new understandings of this little-studied material.[84] This model served as a foundation for an early 1990s technical study on bronzes from Thailand, among other major catalogue undertakings by the technical research labs.

Establishing Technical Expertise

Detail of Renaissance enamel plaque before and after treatment in 1960

Workshop of Master of the Orléans Triptych (French, active late 15th‒early 16th century), The Virgin and Child, ca. 1500, painted enamels on copper, 6 7/16 × 4 7/8 in. (16.4 × 12.4 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, 1906, acc. no. 44.126

Another area of particular strength of the Walters collection was enamelwork from antiquity to the early twentieth century. Though deterioration had been observed on these enamels as early as the 1940s, the first systematic treatment was not undertaken until the 1960s by Peter Michaels.[85] At that point, the mechanisms of deterioration were not fully understood, but Michaels devised a controversial treatment that involved soaking the enamels in water and then drying them, followed by the application of a coating (fig. 20).[86] In 1970 Drayman-Weisser was assigned to one of the enamels treated a decade earlier but that appeared to have some new corrosion, and in 1972 she undertook treatment of another actively crizzling enamel (i.e., enamel in which the glass substrate is breaking down). This began Drayman-Weisser’s deep interest in and understanding of enameling techniques and the mechanisms of their deterioration. In 2003 Drayman-Weisser surveyed Limoges enamels in the Walters collection that had been treated and those that had not to evaluate their condition, which resulted in a publication that is seen as a crucial resource to conservators today in their understanding of glass and enamel.[87]

Training and Outreach

Under Drayman-Weisser’s leadership the Walters remained a key innovator recognized for upholding excellence and professionalism in training. Drayman-Weisser was invited to review curricula for the three existing conservation training programs in the early 1980s as part of the National Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Property (NIC) and also provided feedback and input on the curriculum for a proposed new graduate program to focus on ethnographic and archaeological conservation.[88]

With Drayman-Weisser at the helm, the Walters quickly became an important resource and permanent fixture for the training of object conservators, especially those interested in archaeological material. Correspondence with numerous prospective interns demonstrated the demand for training in the conservation labs at the Walters by the early 1980s.[89]

Bringing conservation out of the labs and into the museum continued to be an ethic of the department under Drayman-Weisser, eventually culminating in the establishment of the Walters Conservation Window, opened in 2011 for the express purpose of establishing connections with visitors to the institution. The Conservation Window was made possible by support from former intern Eleanor McMillan (1962) in honor of her mentor at the Walters, Elisabeth Packard. Nearly fifteen years later, in 2025, the Conservation Window continues to provide access to the Walters collections from new and different perspectives through direct conversation and observation.

Securely established as contributors to the institution beyond conservation treatment, Walters conservators continued to create content for special exhibitions and to curate conservation-themed exhibitions, often popular with the public. Drayman-Weisser maintained the model set by Packard in successfully integrating conservation and technical research into the core values of the museum. She was a firm believer that conservation played a key role in facilitating the mission of the museum, and she understood the potential for conservators to be marginalized and seen only as a service operation. Always maintained as an independent department, conservators contributed to strategic planning, grant strategies, fundraising, scholarly undertakings, public programs, and outreach as well as to building projects and exhibitions. With preservation and collection study work of prime importance, Drayman-Weisser was keen on maintaining high visibility with the public and the museum community at large.

Head of Book and Paper Conservation, Abigail Quandt, working in the laboratory for books and manuscripts

In strengthening and professionalizing the work of the department, Drayman-Weisser made two strategic hires that would support both the needs of the collection and further the goals of study and dissemination of information. She hired Melanie Gifford,[90] a conservator with a strong interest in technical studies, as senior paintings conservator and advocated for the establishment of a new staff position for a Conservator of Rare Books and Manuscripts, Abigail Quandt (fig. 21).[91]

The Walters and a Conservation Legacy

The first fifty years of the Department of Conservation and Technical Research at the Walters Art Museum are notable for its excellence, collaboration, innovation, dedication to a burgeoning field, mentorship, and commitment to dissemination of information and to creating a place for scientific study of art as a core function at the museum. Over the ensuing forty years these core tenets changed little but have adapted to a new and changing field responsive to the needs of museums today. In 2019, the department expanded to the Department of Conservation, Collections, and Technical Research to include Exhibitions, Installations, and Production as well as Collections Management under the leadership of the author. With a conservation scientist position endowed in 2015 and a new position for a preventive conservator, the department is poised to continue its science-based study of its collections and its historic buildings to face issues of a changing climate. In 2024 Conservation, Collections, and Technical Research, in collaboration with the Operations team, led the museum’s efforts in lowering our overall impact on the environment by adopting Bizot Climate Protocols, implemented by the American Association of Museums (AAM) and endorsed by AAM Directors. Beginning in fall of 2024, the museum shifted to science-supported fluctuating seasonal environmental parameters for the collections rather than a single, static annual range, reducing wear and tear on mechanical systems with a long-term goal of lowering our energy output.

As the department approaches one hundred years, it continues to prioritize its core tenets: mentorship, outreach, and contributions to the profession. At the same time it is embracing new technologies and science-based data to inform our practice, working to share access to and information about the collections to an ever-broadening audience, and maintaining a place within the museum that is foundational to the Walters’ identity.

Appendix: Oral History with Terry Drayman-Weisser

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the foundational work on departmental and museum history by William R. Johnston, Terry Drayman-Weisser, Karen French, Abigail Quandt, and Elissa O’Loughlin, which each in their own way contributed to the fruition of this essay. Additionally, though this essay focuses on the first fifty years of the department, I would like to thank and acknowledge former and current staff for their contributions to the field of conservation and to the museum. Many thanks to Anna Clarkson, Museum Archivist and Librarian, for her assistance with archival research for this essay. And finally, a huge thanks to Melanie Lukas and Josh Houston for their editorial contributions, partnership, and expertise.

[1] For more information on the work of Anderson, see Elissa O’Loughlin, “Our Mr. Anderson,” The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 70/71 (2012/2013): 137–42.

[2] Anderson Journals, The Walters Art Museum Archives, Baltimore.

[3] James C. Anderson to George Bruce of Homestead, NJ, January 20, 1909, The Walters Art Museum Archives, Baltimore.

[4] Bruce to F. J. Banks, January 15, 1909, The Walters Art Museum Archives, Baltimore.

[5] Francesca G. Bewer, A Laboratory for Art: Harvard’s Fogg Museum and the Emergence of Conservation in America, 1900‒1950 (Harvard University Art Museums, 2010), 226.

[6] Henry Walters to Anderson, May 8, 1923, The Walters Art Museum Archives, Baltimore.

[7] Stephen Pichetto to Anderson, May 19, 1931, Record of James C. Anderson, The Walters Art Museum Archives, Baltimore.

[8] Anderson to Pichetto, November 16, 1931, Record of James C. Anderson, The Walters Art Museum Archives, Baltimore.

[9] “In Memoriam: C. Morgan Marshall,” Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 7‒8 (1944‒45): 9.

[10] Marshall’s interest in conservation and technical studies was also demonstrated by his involvement outside the Walters. In 1938, he chaired the Art Technical Session of the American Association of Museums conference in Philadelphia.

[11] “Caretaker for the Walters Art Gallery,” Baltimore Afro-American, December 16, 1931.

[12] Recent and ongoing research into William Walters’s stance during the Civil War documents his support for the right to secede from the Union. Given his Southern sympathies, it is notable that Francis was a lifelong and trusted friend and employee of William Walters. For further discussion of William Walters’s wartime political and economic decisions see Kristen Nassif’s essay in this volume, “The Business and Politics of William T. Walters’s Collection of American Art.”

[13] “Caretaker for the Walters Art Gallery.”

[14] “Spent 52 Yrs. as Friend, Confidant, and Guardian of Art Collector,” Baltimore Afro-American, December 26, 1931.

[15] William R. Johnston, William and Henry Walters: The Reticent Collectors (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 295.

[16] Terry Drayman-Weisser, “A Perspective on the History of the Conservation of Archaeological Copper Alloys in the United States,” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 33, no. 2 (1994): 141‒52; correspondence between Walters and Robinson, The Walters Art Museum Archives, Baltimore.

[17] The corrosion stems from the interaction in humid environments of chlorides and copper found in the metal alloys. For more information regarding bronze disease, see Drayman-Weisser, “Archaeological Copper Alloys.”

[18] André was both a restorer and art forger. In addition to his work on archaeological metals now in the Walters collection, André is connected to forged renaissance jewelry in the Walters collection. See: Drayman Weisser and Mark T. Wypiski, “Fabulous, Fantasy or Fake? An Examination of the Renaissance Jewelry Collection of the Walters Art Museum,” Journal of the Walters Art Museum 63 (2005): 81‒102.

[19] The Walters Art Museum Archives, Baltimore; Terry Drayman-Weisser, personal communication.

[20] Drayman-Weisser, “Archaeological Copper Alloys,” 141.

[21] Johnston, Reticent Collectors, 222.

[22] Annual Report, The Walters Art Museum, 1934, 1.

[23] Johnston, Reticent Collectors, 224.

[24] Minutes of Meeting of Trustees of Walters Art Gallery, November 2, 1934.

[25] Bewer, A Laboratory for Art, 8.