Even before the Walters Art Gallery opened its doors in 1934, it was recognized that Henry Walters had spent the last forty years of his life assembling one of the most significant collections of manuscripts and rare books in the country. Yet ultimately, his library’s exact contents—731 manuscripts, as well as approximately 1,300 incunabula (books printed before 1500) and 2,000 later printed tomes—were largely unknown to anyone except Walters himself, who had acquired these according to his personal taste. When the books were bequeathed to the City of Baltimore along with the rest of his art upon his death in 1931, the important work of grappling with what was in the collection began. It was a critical but surely daunting task, and early efforts to meticulously research, document, publish, and display the book collection created an invaluable foundation that future generations of curators and researchers have built on. With the notable exceptions of Roger Wieck and William Noel,[1] that work was, and continues to be, driven by female leadership.

Remarkably, the Walters book collection was overseen by only two curators throughout the first sixty of the museum’s ninety years in existence, a powerhouse of two dedicated and brilliant women: Dorothy Eugenia Miner (1904‒1973) and Lilian M. C. Randall (b. 1931). Miner was hired in 1934 on the recommendation of Belle da Costa Greene, Librarian and Keeper of Manuscripts at the Morgan Library, and was one of the five initial professional staff members tasked with preparing the museum collection for its public opening. Miner selflessly devoted the entire rest of her life to the books at the Walters, working until only two months before her death in 1973. Her contributions were celebrated posthumously in a special volume that was guided largely by her successor, Lilian Randall.[2]

A manuscripts specialist by training, Randall spent much time at the Walters as a student, not only delving into the museum’s manuscripts collection but also forging a close relationship with Miner, who would become her mentor. Randall received her doctorate from Radcliffe College in 1955 and, upon her husband Richard Randall’s appointment as director of the Walters Art Gallery in 1965, put her expertise to work teaching graduate courses in illuminated manuscripts at Johns Hopkins University.[3] Between her continued work with manuscripts and her husband’s position at the Walters, Randall’s connection with Dorothy Miner deepened. In 1974, shortly after Miner’s passing, Randall was appointed Curator of Manuscripts and Rare Books, following seamlessly in the footsteps of the woman who had become a mentor and inspiration. It was, however, an intense moment of transition for the institution, and one of Randall’s first tasks was overseeing the relocation of the entire rare book library from its original home in the palazzo-style building (in what is today the Collector’s Study just off the Chamber of Wonders) into the specially designed, climate-controlled library in the newly constructed building on Centre Street.

Over the next decade she gave countless lectures and curated more than a hundred exhibitions, often meeting an unimaginable pace of twelve per year, with topics spanning the entire book collection and highlighting European, Armenian, Indian, and Islamic manuscripts as well as the early printed incunabula. While some were more ephemeral exhibitions, others had broader reach, such as Splendor in Books (1977‒78), which was curated by Randall and exhibited at the Grolier Club in New York, and Illuminated Manuscripts: Masterpieces in Miniature (1984‒85), which had an afterlife through a still-instructive accompanying catalogue.

Randall’s publications have been both substantial and significant, with dozens of articles and several books to her name.[4] Her greatest contribution during her time at the Walters was arguably her drive to publish catalogues of the manuscripts collection, a goal of Dorothy Miner’s that had never come to fruition. However, Miner had laid the foundation for that work through her decades of research, and Randall built on that through her own expertise. Her first book, based on her dissertation and published before her career at the Walters, was Images in the Margins of Gothic Manuscripts, one of the seminal studies on marginalia in the field of art history.[5] These illuminations are found largely in French and Flemish books of hours, and her careful study of those manuscripts provided the ideal background to tackle catalogues for those cultures with confidence. The meticulous and deep research necessary to achieve that monumental project became the focus of the second decade of her Walters career, during which time Randall’s role shifted to Research Curator (1985‒1997). Her tireless determination to produce the catalogues is evident in the series of grants she successfully won in support of the project, including funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Kress Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Research and Publications Fund, and the Getty Grant Program. Ultimately, with the invaluable assistance of scholars like Judith Oliver and Christopher Clarkson, Randall produced a set of five volumes that still serve as the “bible” for understanding and studying the French and Flemish manuscripts in the Walters’ collection for scholars worldwide today.

Lilian Randall’s lasting impact at the Walters, and her contribution to the field of manuscript studies as a whole, is immeasurable. It is perhaps fitting that the year of this interview (2024) marks not only the ninetieth anniversary of the museum’s opening, but also the fiftieth anniversary of Randall’s appointment as curator at the Walters. She graciously agreed to be interviewed so that we might celebrate her legacy, and the following recording provides the opportunity to hear her thoughts and reflections on her career in her own words.

This interview of Lilian Randall was conducted by Lynley Herbert, Robert and Nancy Hall Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts, and Randall’s longtime colleague and friend Abigail Quandt, Conservator Emerita and former Senior Conservator and Head of Book and Paper Conservation.

Audio Interview

Part 1: Introductions

Part 2: Pivotal Moments in Education

Part 3: Early Days at the Walters Art Museum

Part 4: Experience Working at the Walters

Part 5: Influential People

Part 6: Impact of Being a Female Leader at a Museum

Part 7: Being Remembered and Most Significant Project

Transcript

Part 1: Introductions

Lynley Herbert: Good morning. Thank you for joining us today. Could you just give us your full name, birth date and place, and occupation?

Lilian Randall: My full name, Lilian, L I L I A N, Maria Charlotte Cramer Randall, born February 1st, 1931, in Berlin, Germany. What else?

Herbert: And, well, occupation. But I know you’re retired.

Randall: Retired since 1997. ’96. I now live in South Hadley, Massachusetts, where I grew up. And my father was a professor of history at Mount Holyoke College.

Part 2: Pivotal Moments in Education

Randall: I arrived at my career choice, sort of by a plan that my father had in mind. Each of my four siblings and I were supposed to get our PhD and then embark on whatever life we chose. I’m the only one to whom this really appealed and who followed through. So, that . . . from very early age, I really enjoyed learning.

I knew five languages before I was ten. I was homeschooled. At age ten, I went to a boarding school, commuting from South Hadley to Northampton—Northampton School for Girls, just celebrating its one-hundredth anniversary. It was very strenuous. Ninth grade until graduation at age fourteen. The war years were on by 1945, when I graduated . . . So, I often commuted by bus and train. It was a long commute, strenuous, and then plenty of homework to do after getting home. I only spent the morning hours until 1 p.m. at school. So I missed art classes. Once a week I could stay—art classes were . . . [they] meant a great deal to me at the time. And sports. I did a lot of sports: skiing, skating, tennis, badminton, soccer, whatever. And I excelled in sports at college. So I graduated from Northampton School for Girls when I was fourteen, applied to Mount Holyoke, and they said I was too young. And so I waited a year to get older. Well, I finally achieved that goal. I got . . . I always wanted to get older. Well, here I am.

So I entered at fifteen. I had a great time. Majored in art and history, a double major, which was frowned on. Each department wanted to have a whole major, not half a major, at the time. Now it’s, for a long time already, been totally welcomed and acceptable. I wrote an honors thesis on 19th-century caricature, French and Italian caricature of Napoleon III in France—Daumier, the best known, and unknown Italian caricaturists at the time. So my interest was always in humor and illustrations of events, humorous topics.

So then, so at nineteen, I began my graduate studies in the Department of Fine Arts at Harvard and got my degree there in 1955. Became interested, as for pivotal points, in medieval manuscript studies during probably the second semester of my first year there. So, when I was twenty, the most prominent professors who influenced this choice were Wilhelm Koehler, by then approaching retirement before too long, a marvelous, marvelous professor who taught mainly by asking the question, “What”—very heavy German accent still, though he’d come to the States in the 1930s—“What do you see?” Well, he’d put a slide of an early manuscript or mosaic—“Mosaik”—on the screen. And we students would look and look . . . look; we didn’t know what to look for. He taught us, me anyway, how to really look and comprehend.

The other professor was Professor Harry Bober from, a visiting professor from NYU, who was enthusiastic about manuscripts, especially of the Gothic period, and did a survey of manuscripts from that era and would often say when he put a slide on, “This field really needs work. This needs people to study.” The field of manuscript studies, at least at Harvard, was just beginning to come into its own. There were, of course, collectors.

Princeton was a center for manuscript studies already in 1920s. But it was just when I was beginning my graduate career that the opportunity for doing research and finding new . . . new outlets was opening up. It was like a wave that was just beginning to rise. It crested, as I’m sure you probably know, and it waned by the 1990s. Michael Camille was one of the very distinguished specialists still publishing in the 1990s. So, but, by 2000, perspectives had changed. But the activity during those fifty years was phenomenal. And libraries all through the US and abroad putting on major exhibitions, publishing catalogues, scholarly works were published.

So it was a very exciting time to be doing that. Another pivotal point during my graduate work was a visit to the Walters, as it was then known, Art Gallery and the old library, presided over by Dorothy Miner, a highly respected figure, a marvelous, welcoming teacher who pursued her work since 1934, in what was then known as the old library, the little library in the corner of the building now being used as an exhibition space. The manuscripts were arranged all around in cabinets. The incunables were accessible via a balcony, and there was a ladder you had to climb to get on down.

The old library was a part of the exhibition space. It was roped off with a red velvet rope across the door, and visitors to the museum would sometimes peek in to see this small space littered with papers and Dorothy Miner at work and her secretary, Suzy Vogelhut,[6] hard at work in this very cramped space. So Dorothy Miner’s desk was next to another table, usually loaded with papers, but cleared off when a visitor came to look at a manuscript.

And, and whenever somebody peeked in—I remember a ten-year-old looking in to see what was going on—she would talk to the visitor, sometimes invite one in briefly. Her time was very limited. She was extremely busy. You know, when I had my first visit there in 1952, her exhibition catalogue of illuminated manuscripts published in 1947 was a tremendous success.

And she herself, of course, was inspired by a year of working at the Morgan Library in New York under Belle da Costa Greene, for whom a major exhibition is scheduled this fall at the Morgan Library. This, and it was Belle da Costa Greene who recommended Dorothy Miner to be the, what I think the title, the Keeper of Manuscripts at the Walters. And Dorothy Miner, after Belle Greene’s death, edited the Festschrift for her. It came out in 1954, four years after Belle Greene’s death.

So the inspiration of looking at—first of all, looking at a manuscript, this was extremely rare when I was a beginning graduate student. My first sight of a manuscript was at the Houghton Library. We were asked to sit. Five of us I think went. We sat six feet away from the manuscript because we were told our breath might lift paint off the pages. And William Bond, who was assistant to Philip Hofer, a great collector, stood there, turned the pages of a manuscript on a lectern. Well, you can imagine how much detail we could see from it, even with good young eyes. It was, but it was incredibly thrilling to see it. And that was before my first visit, when I actually handled a manuscript at the Walters. When I began doing serious research at the libraries abroad, Paris and London, I was so apprehensive of holding my breath when the manuscript was set in front of me. I had to learn how to breathe and study and work with the manuscript at the same time.

So those were pivotal moments. Some of them, I would say.

Part 3: Early Days at the Walters Art Museum

Randall: I was appointed January 1st, 1974. Dorothy Miner had died in May 1973. It’s still an irreparable loss, a terrible loss. And to be in the space she had filled and begin work there was . . . I was always conscious of her ghostly presence somehow. I often went in at night because I worked during my first months there, because there was so much other work to do during the day. I lived not too far away. I could get there. It was very eerie. The wood would creak. You didn’t know what, what spirits might be inhabiting the premises because these were Dorothy Miner’s premises. Definitely.

My first . . . Well, what I did in the evenings for a couple of hours was to sort whatever papers she had left on her desk. Stacks and stacks, letters to be answered, work in progress, and so on. So, it was very momentous as an introduction. But during the daytime, there was always a great deal to do. 1974 marked the opening of what was called the new wing, the addition to the existing building where there was no exhibition space, which was very frustrating to the curators, especially Dorothy Miner, whose heart was set on creating exhibitions and exhibition catalogues. And they had to be held offsite—Baltimore Museum, for instance.

And it was Dorothy Miner who designed the Rare Book Room that you are now sitting in. And it’s very interesting to me that she had aimed to house the manuscripts in a dark room, which could be closed to visitors, not interrupted. No, for their own safety. It’s like a vault, you might say. But that’s where she planned to work. And so, so it was her design and the incunables, everything accessible: the printed books and so on, plus manuscripts of course.

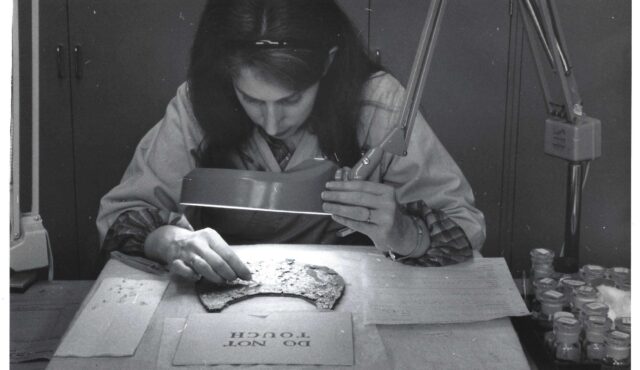

So, that was a major accomplishment, but everyone’s focus was on planning exhibitions, when I joined the staff, for the opening. Every department was planning and preparing for . . . in the conservation department, Elisabeth Packard. So, and Dorothy Kent Hill . . . so, various. And my responsibility was to plan an exhibition of Armenian manuscripts, a very important part of the manuscript collection at the Walters, and an enormous catalogue had just recently been published by Sirarpie Der Nersessian. It took about fifteen years, and Dorothy Miner, I don’t think lived really to see that, but she had commissioned it, and it’s a magnificent publication.

Well, that was a heavy assignment. In fact, the whole experience of being a curator in a place where I had come and worked on manuscripts off and on during my previous years, especially as a student . . . it was a steep learning curve, I would say. I was full of enthusiasm, I had energy to burn. It was very fortunate because we did have a family of three children, two still at home. No outside help ever, because salaries were not conducive to that kind of thing. So it was do it yourself. And it was fine. So.

It so happened that one, not a month or five weeks after I was appointed curator—and here comes a pivotal point—my husband and I attended a gala opening at the Metropolitan Museum in New York for the Angers tapestry exhibition. I think they had never been loaned before. It was once in a lifetime, magnificent. So, a candlelight dinner at the museum with place cards. So, after looking at the exhibition, soon everybody found their places at the table, and I didn’t know either of the two gentlemen by my side, but it turned out that the one on my left was extremely interested in what I was doing.

And I, five weeks into my new position, which was the dream job as far as I was concerned, full of enthusiasm, told them about the Armenian manuscript show that I had to do. And he said to me, “You need a grant. I’ve been living on grants and scholarships all my life.” I said, “A grant? No, I don’t need a grant. You know the manuscripts are all here, there are no loans.” “No, no, absolutely.” Well, turned out he was the deputy chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities. His name was Douglas Kingston.[7] Again. And he persuaded me; I guess there was good food and wine, so he persuaded me. All right. And I said, “There’s no time. This is February. These grants take a year.” “No, no,” he said, “There is a way you can just send a letter. No form needed to be filled out. Just a letter, a chairman’s grant. I think the limit is 14,000.”

Well $14,000 in those days represents, I don’t know, represents ten times that nowadays. It was a large sum of money in those . . . well, it was the equivalent of my salary, in fact, a year’s sum. So I wrote a letter, persuaded by his, he was a very erudite, charming former professor at Bryn Mawr college, and . . . the National Endowments had been founded in the 1960s, and they were avidly looking for projects in those days.

So I received the grant, and then I had tremendous trouble spending it. But, so Dorothy Miner had always exhibited manuscripts, and in many, like many other places, and, a very good idea, lying flat or slightly raised. Well, it then began to become more prevalent to raise them on plastic stands. So, I found a place to commission those, raise them a bit higher. I installed a microfilm reader. I made a microfilm myself. So viewers could print out a color picture of an Armenian manuscript page. Well, the microfilm, as it turned out, kept slipping off several times a day. I had to go down to the gallery and put it back on. I don’t know, but Xerox machines, again, were quite a novelty in those days, you push a button, get a copy.

So that was an innovation made possible, and then a publication about the Armenian manuscripts was facilitated by that grant, and then the NEH had me write an article for their bulletins. So it created quite a stir. And of course, the Armenian manuscripts are phenomenally beautiful. So that was extremely rewarding.

So everyone, all my colleagues whom I’d gotten to know—we’d lived in Baltimore, you know, about eight years before I joined the staff. I’d been teaching graduate courses at Johns Hopkins. I’d been assistant director of the Maryland State Arts Council, giving money to cultural institutions, and so, did a variety of things, while also completing a book on George Lucas. You know, I began in the mid-1960s after we moved from Boston to Baltimore and where my husband’s task was to raise money, supervise the architecture of the new building, discuss with curators what their needs were, what their wishes were, and so on. So he was very busy. Children were still quite young, so I was, I needed a project. I just sent off a book to—my book on marginalia based on my dissertation—to the University of California Press, and I needed a project to focus my mind on, in addition to entertaining, a social life that was very active with wonderful people in the community. I got to know the curators, Dorothy Hill, and Elisabeth Packard. We went to each other’s homes and we became friends. It was a marvelous time.

When that book, unfortunately, took the book on the diary of George Lucas, published by Princeton University Press, I was only able to finish the one index—it’s a big two-volume work—in 1977, while also doing exhibitions at the Walters and greeting visitors and so on, and doing what was necessary on the job. But it was really a double load. I also began raising money from the NEH to get the catalogue started, to bring in consultants, marvelous consultants. And, Christopher Clarkson, for one, for Abigail. You got to know, like, well, was he here when you came, Abigail?

Abigail Quandt: No, no. I mean, I, I met Chris many years later. Actually, it’s funny, it was when I was still a student at Smith College. And my mother at that point was working at the Library of Congress. So through her, I met Chris, also Peter Waters, Head of Conservation, and Don Etherington. So there were three, three of the three Brits that had been brought over. And Chris actually gave me my very first bookbinding lesson. This was in 1975, when I was doing a typography course at Smith. And our teacher knew a lot about design, but nothing about bookbinding. And so, so I went in during our January break, I went home, got some lessons from Chris, went back, taught all the rest of my classmates how to bind their books. So that’s what got me started.

Randall: That’s wonderful. He came to me.

Quandt: It was 1979 when he was here. Right?

Randall: At the Library of Congress. Yeah, he approached me because the position he had there didn’t allow him to do what he excelled at, I think. He yearned to work with manuscripts. So in a way, he off—so then I raised, I applied to the NEH for funding to bring him as a consultant, and he did an incredible job, and his notes are in the Rare Book Room, or they were. They’re very precious, magnificent. And slides he took . . .

Herbert: Yeah, we still use them.

Randall: That’s wonderful heritage. So that, you know, brings me, well, my regular assignment was to do twelve exhibitions a year in the new galleries. Well, six. Well, because I had to rotate; six exhibitions of the Western manuscripts, six of them Near Eastern examples, about which I knew very little. They were not my field of study at all. But with the Western manuscripts, that was a tremendous load. It meant, of course, an attractive title to bring in the public, a theme for each one, publicity for each one, writing the labels, which were typed by a wonderful secretary named Kathy Davis. You know there was a lot of do–it-yourself work involved here at the time. The staff was still very small, and so, that enthusiasm, goodwill, it was a wonderful atmosphere to work in.

So those exhibitions, I tried to tie them into key events. I remember, just for instance, the United Nations, the year of the woman. So I keyed into that and always made sort of a provocative title for each one. And then, and enjoyed—it gave me an opportunity to really get to know the collection as well, and to canvas it, so.

In addition, there were, of course, visitors to welcome. There were quite a few in those days, especially after the new building opened in November 1974. I instituted the practice of asking visitors to wash their hands before they came. There was a controversy, and it’s still going on, “So do we wear white gloves or do we wash hands?” So it seemed, you know, opinion really suggested washing hands. That was done at the Morgan Library as well. So, and Christopher de Hamel, who is a major figure in manuscript studies, was at Sotheby’s for many years in charge of the manuscript section. He once told me, “I always knew when people had been to the Walters because the first question they asked is, ‘But where can I wash my hands?’”

Herbert: Excellent.

Randall: Christopher is a good friend, I haven’t seen him much in recent years, but anyway—John Plummer, also a good friend, at Morgan Library as a consultant. Anyway, so I began really work on the catalogues in 1977. Well, because the timing was opportune; the NEH was looking for good projects. There were, Yale was doing it, I think the Beinecke Library. Other catalogues were being compiled, manuscript catalogues at the time. So it was an opportune moment to seize the day. Judy Oliver, who came on board and assisted with the descriptions, was very effective in that regard. She was a student of John Plummer’s, had gotten her degree at Columbia.

But, so all that had to be supervised. So it was a very, very busy, exciting, productive time.

Part 4: Experience Working at the Walters

Randall: The staff was always small, really, and utterly dedicated. A number of people, like Dorothy Miner, had been there since 1934, and there were—they worked and enjoyed their work, loved it, worked very hard, and that’s a tradition that continues, I think, to this day. And it was a great, wonderful atmosphere to witness the enthusiasm of these people. Winnie Kennedy—Winifred Kennedy—another one, Bostonian, her life spent as registrar. Utterly dedicated. And that was how I felt and I think how people who are now working there still feel, that it was an act—but, people worked hard, but they also knew how to relax.

And, so, after hours, Dorothy Hill gave an annual New Year’s party; she’d make wonderful eggnog. Elisabeth Packard, who lived in an octagonal house in Lutherville, cooked marvelous dinners, you know, and we had them over, and entertaining was a big part, also, to make friends in the community and people who were interested and patrons and so on.

That was a life that was very different from the one I had. But my husband, who grew up in Baltimore, he thrived on these social activities as well as hard work. He had been an intern in the 1940s at the Walters. I don’t think anyone knows; there was an unbelievably talented curator. I have not looked him up and I’m sure it’s online. His name was Marvin [Chauncey] Ross. And so my husband was at Princeton, I think the summer he was a sophomore. He had been in the Army for two years, serving abroad, through the last two years of the war, came back, so delayed his education at Princeton that summer. He was an enthusiast from childhood on arms and armor. He had read all the books, you know, featuring knights in shining armor, collected armor, knew about swords and guns and cannonballs and, I don’t know, somehow Marvin Ross must also have known about that kind of thing. But I’m sure it introduced him to a realm of different activities here at the Walters. He hardly, never really told me in detail, which I regret. He never wrote what that experience was like, but it was life changing. And it determined his major and his decision to go into museum work, definitely.

Of course there were certain disadvantages for me to be the wife of the director. That was not an ideal position, but we were both so madly keen on what we were doing that . . . what, I don’t know, with this, we did what we could, and it was tremendous hard work fundraising. As you may know, there had been attempts to add a new building already, to raise the money, to bond issue, to go through the city, in the 1950s, because all the curators, everyone, conservation department, they were all short of space; and that failed. So there was tremendous impetus to get the work done. And fundraising was a relative novelty because at the time, the trustees gave a generous amount every year, but fundraising was not yet in fashion, you might say, was not yet the thing to do.

So, that happened really in the 1960s, in going far afield. And there was tremendous interest from funding organizations. So my work on the Lucas book, in fact, I’ve always applied for, was from the Kress Foundation, where your director is headed, to be the head of that team.[8] Well, there was someone named Mary Davis at the Kress Foundation who looked very fondly at the Walters and made available funding for exhibitions and so on. But it was a, it is and remains, as you know, a prime need for institutions like educational and museums. So that was what was going on at the time.

Part 5: Influential People

Dorothy Miner was certainly—I mean at age twenty-one, just like Chris Clarkson’s encounter with Abigail. Knowledgeable expert. Oh, tremendously admired, tremendously mourned! She had died only in May 1973. By the time I came and joined the staff, her presence was terribly missed still. But anyway, so that would be one. But then in my research, I was able to befriend many marvelous people.

Early on, 1952, I had a summer planned to Brussels, Brussels art seminar. There, I met somebody named L. M. J. Delaissé, pronounced “duh-LAY-see.”

Quandt: Oh, yes.

Randall: He became a very dear friend, close friend. He moved to Oxford, we visited there, I met his children. He was remarkable. He had been severely wounded at Dunkirk.

Quandt: Very much.

Randall: And he married the British nurse who tended him back to health.

Herbert: That’s amazing.

Randall: They had four wonderful children. So, he was invited to come to Harvard when we were living, when my husband was at the Boston museum; we lived in the area. We often saw him. It was a delight. And he was invited to speak or teach at different organizations, places in the US. So, a dearly missed friend.

Who else? John Plummer, at the Morgan Library, and then later his assistant, Gregory Clark, set wonderful examples: hard work, but sense of humor and lively personalities. And François Avril, who was head of the manuscript collection at the Bibliothèque Nationale; again, a friend, became a real friend. He allowed me to take photographs. I took all the photographs for my book on marginalia. I took them all myself. I bought a [indecipherable]; I learned how to fix it on a stand, and all of it. Photographs allowed me in the back room because obviously in the study room, the big hall where people were examining manuscripts, it would not have done to do them. I also took photos—it was allowed to take photographs at the British Library. If you can imagine . . . that was a—so, those were days of tremendous support for manuscript studies.

The field was really thriving and people were being encouraged to work. And there were many people engaged in that. So let’s just—and of course, Roger Wieck, and other . . . Will Noel, sadly passed away.

Quandt: What about Michel Huglo? I remember him.

Randall: Michel. Lifetime friend.

Quandt: Yeah, he was such a sweet man.

Randall: Yes, yes. I would visit him and his wife. Yeah, Michel was a consultant and he would sit around the corner where the incunables are shelved and when he saw, looked at antiphonaries he would chant, begin chanting—couldn’t, couldn’t help himself to be inspired by . . . I should have had a recorder but I don’t have a—

Herbert and Quandt: [Laughing]

Randall: Anyway, yeah, that Beaupré Antiphonary, that was one of the biggest coups of Dorothy Miner’s. Of course, money was in very short supply to buy, and she acquired the Beaupré Antiphonary—it’s divided in four volumes, now missing three—for eight cents. That’s for—

Herbert: Eight cents?

Randall: That was the postage. That was in the 1950s. The letter of inquiry—when it became known that in the Hearst collection there were works of art, tapestries, and so on to be given away, and she—it was known or somehow Dorothy Miner knew or suspected that the antiphonary was there, was in California. I visited the Hearst estate once. Anyway, it turned out yes. The answer was yes. “Would you like it? We’ll ship it to you.” What and—I’m sure there’s correspondence. And it should be in the file about that.

Herbert: Yeah, I believe there is. Although I never knew how—I knew she paid for the postage, but I didn’t know it was only eight cents. That’s amazing!

Quandt: And it arrived in a big crate or something.

Randall: It’s now 68 or . . . even that would have been a bargain price. Magnificent, magnificent manuscript.

So the community of scholars internationally, automatically I’m sure you all find the same . . .

Herbert: Yeah.

Randall: . . . becomes, has a great deal in common.

Part 6: Impact of Being a Female Leader at a Museum

Randall: Well, as far as Dorothy Miner goes, Dorothy Hill, Winnie Kennedy, Elisabeth Packard—they were all very early appointments and no question but, I mean, what was the attitude toward women in 1934? Well, you know, not all that friendly. Belle Greene! I mean, she cut a wide path, a swath, but nobody ever questioned her, as far as I know. I mean, they probably somewhat . . . her authority and they—this group of people in the middle of the Depression, the people who came to the Walters, they were infused with that energy.

I don’t think anyone had any self-doubt. If they did, it soon vanished in the atmosphere of applying yourself to your work, do the best you can, spread the word, educate, do research. There was—and there was very little room for antipathy or bias. People were won over by, you know, the sincerity and the quality—utter golden quality of these people. It was so recognized they all had a magnetism, and I think Elisabeth Packard, and . . . Dorothy Hill was a bit more sedate, and she was a great archaeologist, accomplished a great deal. And Dorothy Miner—I mean, they all had—they didn’t, you know, they weren’t vociferous in any way, but they represented sterling quality. And, you see, sterling quality—I don’t know, even the most hostile person might be swayed to be impressed. One just couldn’t help it. There’s a magnetism there that I was very fortunate to experience.

And, you know, and I tried to pass that on, this enthusiasm, which was alive in the Rare Book Room. And I found the Friends of the Library Manuscript Group, a group—we met monthly. I prepared some presentation. It was much enjoyed. It was not for money. I wanted to do something not for fundraising for a change.

So much of what we had to do was about the fundraising. Unlike Dorothy Miner, I was in a position to cook many, many dinners for visiting folks—the architects of the building, people, trustees, friends—make friends that way. But my husband was very keen on hosting at home, not at a club. Make it a personal connection. So, I have a big recipe file. We had this small kitchen. People wondered, “Oh! An old-fashioned . . .” Everything very old fashioned. “How did you do that?”

Herbert: [Laughs]

Randall: And then I loved setting a table. All that I was involved in. So, without a maid and, of course, we attended these wonderful dinners, sometimes a butler with white gloves. I felt, you know, it’s really a bit odd, you know, but I don’t know. The intention was good. So this is what the spirit that the original . . .

Now the women, now there was Marvin Ross. And he was—there was Edward King, who was director at the Walters. Marvin was a great scholar; Ed King, I think, was paintings expert. Bill Johnston, of course, was—but I think of Ursula McCracken, who was a devoted friend to Dorothy Miner, especially during her final months. So, helped her clear her papers and so on. Wonderful editor; edited the Festschrift. We knew that Dorothy Miner was ailing for some time and so set a secret Festschrift in motion, but it wasn’t published until the year after her death in 1974. Oh, there was also Eleanor Spencer as a friend, a friend of the Walters, professor of Goucher, specialist in manuscripts, also a fellow graduate long before my time.

So. Anyway, so that was, you might say, the spirit of the age in the world of rare books and manuscripts. Yeah. Come hell or high water. I mean, the problems of the world . . . as we—terrible, always. But it was a close-knit community of kindred spirits.

Part 7: Being Remembered and Most Significant Project

Randall: Well, first of all, moving the books to the Rare Book Room where you’re sitting, that happened in September 1971. So that. Establishing notebooks with illustrations of all the manuscripts for handy reference. Trying to make material available. I don’t know how much of that. The space was at a premium already when I was there.

I kept a record of all the exhibitions I put on, the smallish exhibitions, each one like ten or twelve manuscripts,each with snappy titles for the Western ones. I don’t know where those records are, but I had people not only sign the ledger when they came, research scholars, and many did come, but also kept on file the manuscripts that they saw, which I think is still being done. So, I don’t know what is remembered for that kind of thing.

I think the work on the catalogues, and I began that, as I said, by Chris Clarkson essentially came at a moment . . . I knew I wanted to do a catalogue to get the collection better known, so that triggered it before I was ready because I continued as doing big exhibitions, major ones— you’ll see that in my CV—until 1985. Then I was supported by eleven successive NEH grants, which had to be renewed, applied for, reported on every six months. Of course, you always promise more than is possible. Well, that I could achieve. But anyway, it worked. So, I went off salary; the Walters did not pay my salary. They did not approve of my doing this catalogue so that, among other things, remained unmentioned.

But, so . . . But, you know, I had great cooperation from, I found, the publisher, Johns Hopkins University. Wonderful people there, the editor, Henry Tom, Carol Ehrlich, my patient editor, went back and forth, and really was able to focus. So within three years, the first volume came out; I think those catalogue volumes, you know, prove helpful.

I’ve never gotten feedback. I guess that happens. I once met a scholar when I moved to South Hadley in 2016. I lived in Milton, which is a suburb of Boston, often went to the Houghton Library to do some research. And once there was a little cloak room. And I attended lectures also at the Houghton Library. I heard a scholar while I was working on something in the reading room at the Houghton Library ask for something related to manuscripts. [Indecipherable.] This was—when would this have been? 2010, roughly, and I happened to meet him at the cloak room where we had to check everything except pencil and paper before going into the reading room. And I said, “Are you going to see the manuscripts? Seems to me I heard you request—” “Oh, yes.” So we stood and talked maybe for five minutes, and his name was, a German scholar, [indecipherable]. And he just, “Oh, you wrote those catalogues.” That was the only reaction I ever had from scholars.

Herbert: I’m going to take this opportunity and tell you that they are invaluable. We use them literally every day in this room. But I have scholars reaching out from all over the world. And the first thing they say is, “I have the Randall catalogue entry, and, you know, that’s giving me most of what I need. But do you have pictures?” So they are being used everywhere all the time. [Indecipherable chatter.] It is such an impact; you have no idea how incredible they’ve been.

Randall: I worked and worked and worked to finish, and the last volume—the first volume was one lone volume. And of course the introduction tells you—it’s brief but it tells you a lot. And at the end of the introduction, also acknowledgments, Dorothy Miner and my professors that I mentioned, I mentioned at the beginning, and . . . that it’s, it’s interesting—I know Barbara Shailor who did those magnificent catalogues on manuscripts.[9] Well, I wasn’t able to build on, on that, partly, you know, due to age—fifties until I was sixty-five [indecipherable]—exactly! When those catalogues came out, Barbara Shailor was, you know, like thirties, I think. And it was the beginning of a wonderful career. Consuelo Dutschke, another name in manuscript studies.

But, it didn’t matter very much, but it would have been a pleasure to know, so I appreciate you letting me know. And I think people probably think I’m dead, you know, by now. Certainly.

Herbert: Well, now they’ll hear this and be like, “Oh my gosh!”

Randall: But, and I still miss the excitement. There’s nothing like it, to work for the manuscripts, as we all know. And working with the conservation department, yeah! That was, that was a novelty. A very wonderful step forward. An expert, like Abigail Quandt, coming in with tremendous amount of work to be done. One thing Christopher Clarkson did immediately, he created [indecipherable] boxes. So it made me aware of conservation issues and . . .

Quandt: Yeah, he also taught the staff how to make the plexiglass book cradles.

Randall: Exactly.

Quandt: So, John Klink was one of his first trainees. Yes.

Randall: And “the boys,” as they were known. Now they’re in their sixties or seventies. But it was a wonderful team spirit. And I trust it still is [indecipherable]. So I hope that it . . . So, my work to be remembered—I don’t know—You don’t really want a statue of Dorothy Miner watching over Mount Vernon Place. [Laughs] No!

Herbert: [Laughs]

Randall: It’s what you’ve done and organized. It should be helpful, along the way, toward the future. There’s nothing like the actual experience of seeing. And sometimes, you know, I could have bought something in a late 19th-century binding just for people to feel the weight. So that actual contact. Yes. I also gave classes and lectured at lectures, I’m sure after doing a visit—and visits to the conservation lab—you know, so much to learn, conservations, part of, you know, binding condition, and it’s an ongoing learning process.

It’s very rewarding to anyone who is willing to live on, and can, is able to, you know, on salaries that are, you know, affordable for the museum. But the fundraising era really began with my husband and it went on and on, beyond the building, planning of every detail, lovingly planning. Fundraising continued and eventually affected his heart and led to his death. So, fundraising remains essential of education and museum institutions. I know that, but I don’t know the role of the national endowments now that they’re still active . . . which is of great help. The Kress Foundation remains active, Mellon Foundation. I had many subsidies for the catalogue publication, so there was also the work, and then we applied for funding in addition to the . . . Well, so I think what is still useful, that is, just like Dorothy Miner’s published works. And there are notes in the files; there’s wonderful correspondence in the files that I encouraged, I don’t know, I think might have been Roger Wieck, some, some time, somebody to go through—and letters from Sidney Cockerell to Dorothy Miner. You know?

Quandt: Oh yeah. Yeah, this amazing tiny handwriting.

Randall: And the manuscript that he gave it all to Sidney Cockerell. And Eleanor Spencer! We mentioned her earlier. Excellent manuscript scholar. But you must meet the people, obviously, of the current generation. And you still make them wash their hands?

Herbert: Always. Absolutely.

Randall: If nothing else, okay, there’s something to remember me by.

Herbert: Yeah. It continues. They still sign the register when they come, too.

Randall: And they’re awed by what they see. And it’s very inspiring, very inspiring. Hard work, but very inspiring.

[1] Roger Wieck worked as Associate Curator of Manuscripts and Rare Books at the Walters from 1985 to 1989, before beginning his storied career at the Morgan Library, where he has held the title of Melvin R. Seiden Curator and Department Head of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts since 2015. He is best known at the Walters for his exhibition Time Sanctified and its accompanying catalogue, Time Sanctified: The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life (Roger S. Wieck, Lawrence Raymond Poos, Virginia Reinburg, John Plummer; George Braziller, 1988). William Noel was the Curator of Manuscripts and Rare Books at the Walters from 1997 to 2012. Soon after his appointment as curator in July 1997, he and Randall became great friends, and he dedicated his facsimile of the Walters’ William de Brailles manuscript, W.106, to her. As Randall’s successor, Noel left an indelible impact. His dynamic advocacy for open access and the digitization of manuscripts shifted the field at large and made the Walters a world leader in ensuring the accessibility of medieval manuscripts—a legacy that lives on through sites such as Walters Ex Libris: https://manuscripts.thewalters.org/. He also led a renowned project to decipher the Archimedes Palimpsest, which was the subject of his final Walters exhibition, Lost and Found: The Secrets of Archimedes, and publication, The Archimedes Palimpsest; 2 volume set (Volume 1: Catalogue and Commentary; Volume 2: Images and Transcriptions), edited by Reviel Netz, William Noel, Natalie Tchernetska, and Nigel Wilson, Cambridge University Press for the Walters Art Museum, 2011.

[2] Gatherings in Honor of Dorothy Miner, edited by Ursula E. McCracken, Lilian M. C. Randall, and Richard H. Randall, Jr., Walters Art Gallery, 1974.

[3] Radcliffe College was a women’s liberal arts college in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that merged with Harvard University in 1999. Randall’s papers are archived at Harvard Library, which hosts a site that includes her biography as well as an in-depth finding aid for related materials, https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/9/resources/394.

[4] A select bibliography can be found on her page in the Dictionary of Art Historians: https://arthistorians.info/randalll/.

[5] Images in the Margins of Gothic Manuscripts, University of California Press, 1966. Randall still delights in the fact that some of the playful illuminations she photographed and published in her book inspired those animated by Terry Gilliam for the 1975 cult-classic film Monty Python and the Holy Grail. She continues to find joy in introducing marginalia into popular culture, most recently serving as a consultant for the independent video game company Yaza Games for their latest release, Inkulinati, in which players can battle marginalia, including some from Walters manuscripts: Inkulinati | Yaza Games.

[6] Randall perhaps refers here to Sarah Vogelhut, Secretary to the Librarian ca. 1964–72.

[7] Randall here may mean to refer to Robert Kingston, who served as Deputy Director of the NEH in 1977.

[8] This recording occurred soon after Julia Alexander (1967‒2025) had ended her tenure as director at the Walters and taken the position of President of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation in New York City.

[9] Randall here refers to Barbara Shailor’s Catalogue of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University (1984-1993).