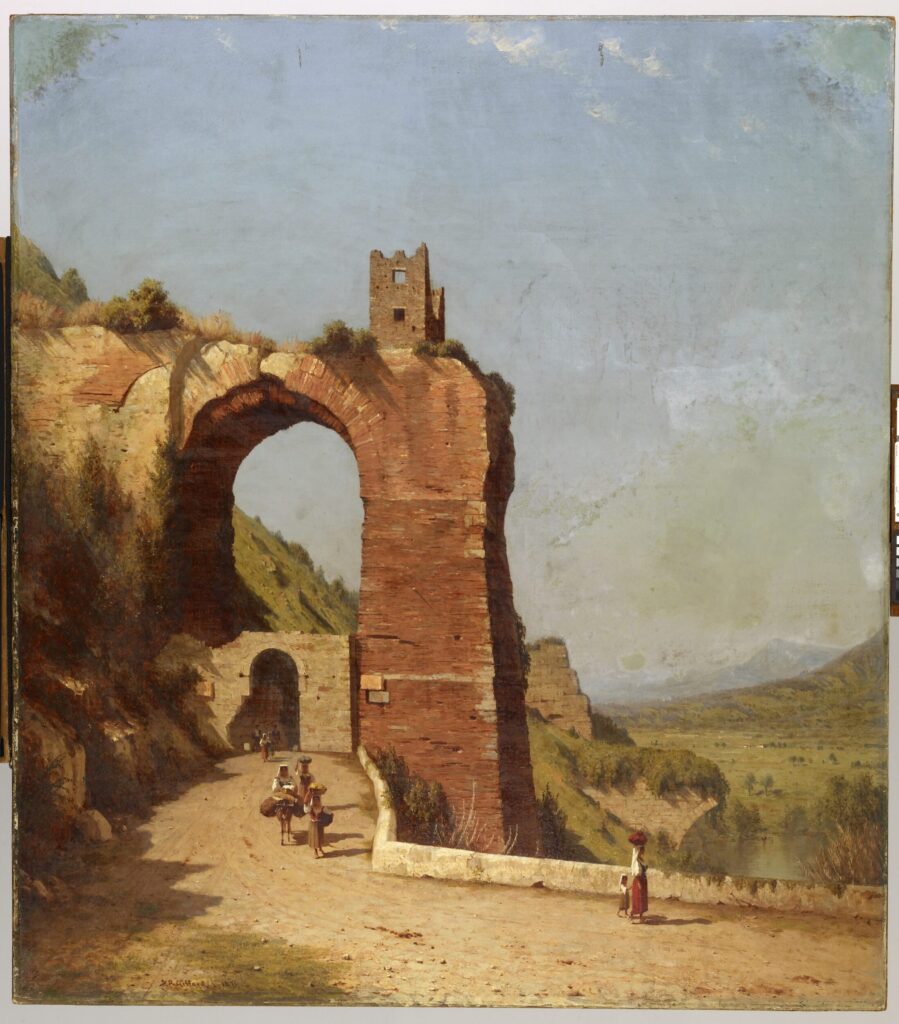

In 1982, The Arch of Nero, a large landscape painting signed and dated by Sanford Robinson Gifford (1871), was bequeathed to the Walters Art Gallery.[1] Although it was a striking painting, with coral-colored Roman and medieval ruins under an expansive sky, rolling countryside into the distance, and multiple figures in the foreground, it was not exhibitable. What started as a small and localized damage to the canvas and paint surface had, through subsequent restoration campaigns, grown larger and larger. These early campaigns abraded, stained, and overpainted the original paint surrounding the damage. By the time it came into the Walters collection, most of the once-blue sky was now an angry mass of green and brown—the result of highly discolored restoration paint and varnish, which had aimed to match the artist’s original colors. The major disruption in the sky effectively destroyed Gifford’s subtle diffusion of light and atmosphere, consistently cited during his lifetime and today as the defining characteristic of his work.

Sanford Robinson Gifford (American, 1823‒1880), The Arch of Nero, 1871, oil on canvas, 45 1/16 × 40 3/16 in. (114.5 × 102 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Bequest of Mrs. Priscilla Ridgely Schaff, 1982, acc. no. 37.2599 after recent treatment (left); installation detail from Selections from the North American Collection: People and Places, 2024. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (right)

Consequently, The Arch of Nero, cited by Gifford as one of his “chief pictures,”[2] was long out of public view and believed to be lost by scholars until recently. Innovations in conservation materials since prior treatment campaigns, along with singularly focused time during the COVID-19 pandemic, helped to restore the nuanced atmosphere of this once thought-to-be-lost painting. Now, after more than forty years in storage, where it remained between conservation treatments that endeavored to remove the extensive discolored restoration and more sensitively reintegrate damages, it has finally been exhibited at the Walters (Selections from the North American Collection: People and Places, 2024) (fig. 1).

The Arch of Nero depicts an arched fragment of the Roman aqueduct Anio Novus, finished in 52 CE, with part of a medieval tower perched on top.[3] The arch, known as Il Ponte degli Arci, is located just outside of Tivoli. Behind and to the right of the arch is a glimpse of an even older aqueduct, the Aqua Marcia, built between 144 and 140 BCE. The site, which had become erroneously referred to as “Arch of Nero” sometime in the early nineteenth century, had attracted artists in the past, including Claude Lorrain, J. M. W. Turner, and Thomas Cole.[4]

Born in 1823 and raised in Hudson, New York, Sanford Robinson Gifford left Brown University after his sophomore year to study to become a portrait painter in New York City. However, sketching from nature on a “pedestrian tour” of the Catskill Mountains and Berkshire Hills completely changed his trajectory. As he explained in an 1874 letter to clergyman Octavius Brooks Frothingham, who also wrote on art topics for the New York Daily Tribune, “these studies together with the great admiration I felt for the works of Cole developed a strong interest in landscape art, and opened my eyes to a keener perception and more intelligent enjoyment of nature. Having once enjoyed the absolute freedom of the landscape painter’s life I was unable to return to portrait painting.” [5]

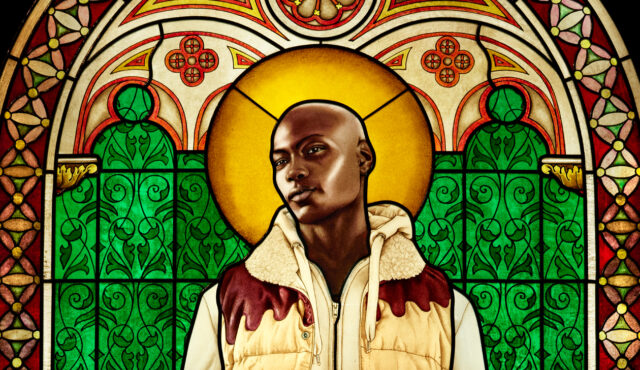

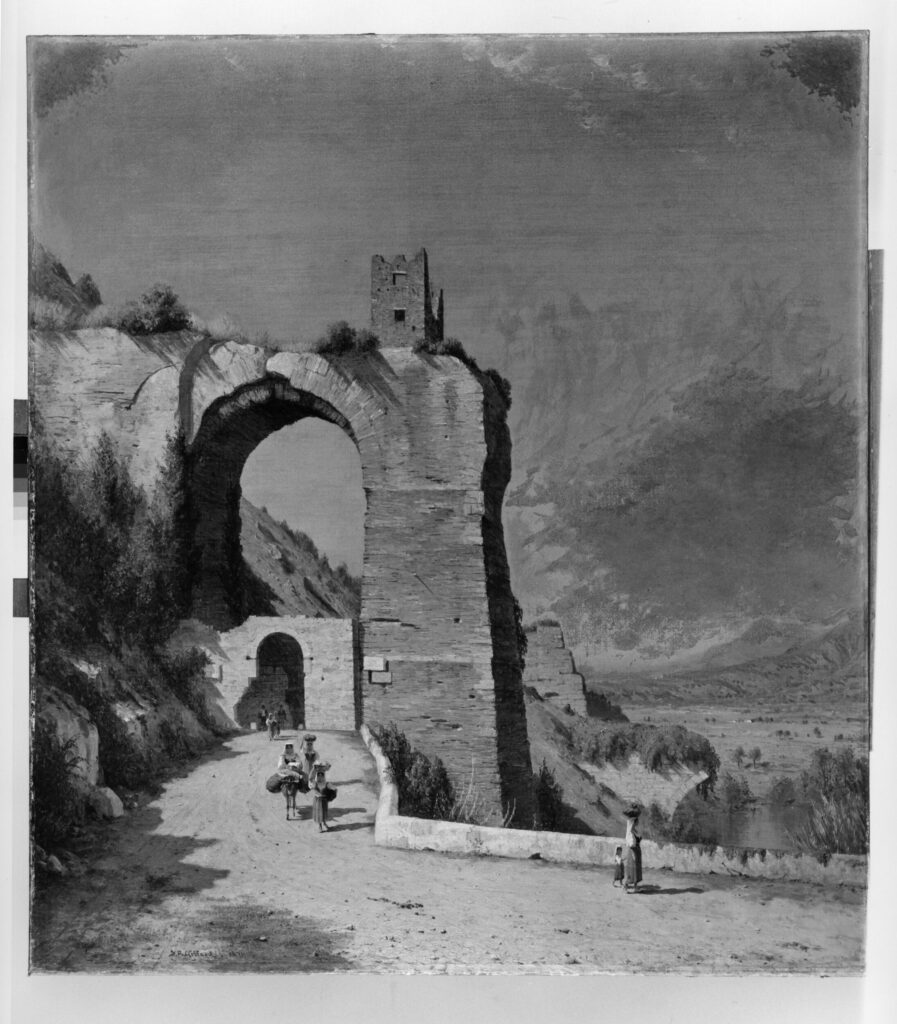

Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848), The Arch of Nero, 1846, oil on canvas, 60 ¼ × 48 ¼ in. (153 × 122.6 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art (on long-term loan from the Thomas H. and Diane DeMell Jacobsen PhD Foundation). Image courtesy of the Thomas H. and Diane DeMell Jacobsen PhD Foundation

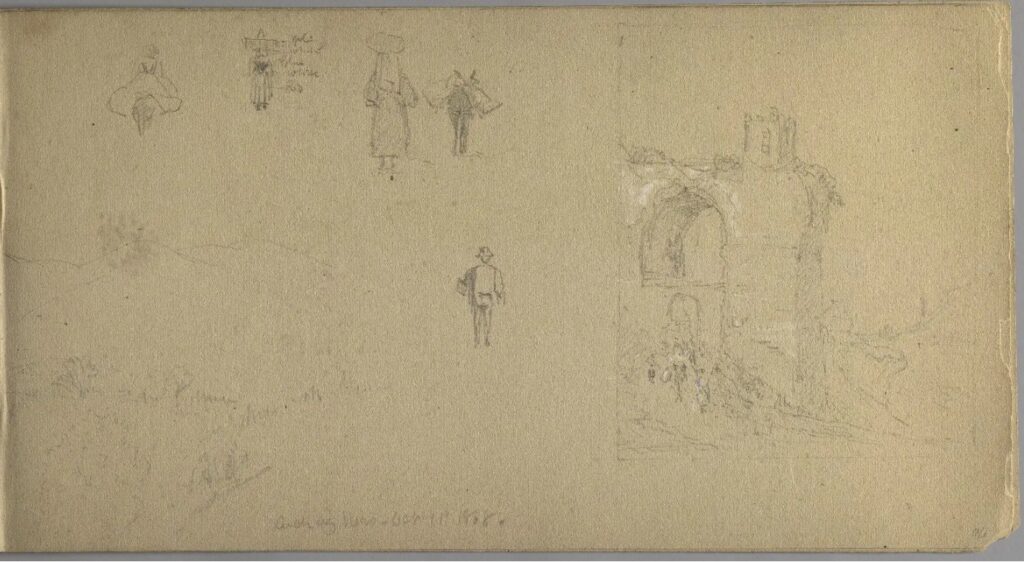

Gifford traveled extensively to find scenic material, mostly along the East Coast of the United States but also internationally. Like many adventurous nineteenth-century American painters, he journeyed to Europe, joining friend and fellow painter Jervis McEntee (American 1828–1891), in October 1868 in Rome, from where they traveled to nearby Tivoli. Inspired by Cole’s painting The Arch of Nero from 1846, which shows the arch viewed from the west (fig. 2), he visited the same site and made several preliminary studies for what would become the painting now in the Walters. Several pencil sketches of the site and the surrounding area are preserved in a sketchbook at the Brooklyn Museum.[6] One sketch closely anticipates the Walters painting, viewed from the east and drawn in a vertical format with the arch dominating the width of the picture and ample sky above the landscape (fig. 3).[7] In addition to drawings, he made three painted sketches from the site, viewing the arch from both the east and west. He also kept a journal during his trip that correlates dates and locations with his sketchbook. His journal entries, sent to his father, would, as he said, “serve the double purpose of letter and journal, and be an economy of time.”[8] Excerpts from his experiences in and around Tivoli, most notably at the site that would be the material for the Walters’ painting, include:

11. Walked a couple of miles out on the road to Subiaco to the picturesque “Arch of Nero.” This is a fragment of the great Claudian aqueduct, 46 miles long, which at this point went through the mountain and reappeared on the campagna near Rome. This was the subject of one of Cole’s finest pictures.[9] He relieved the arch magnificently against a great white cumulus cloud. On the top of the massive pier are the ruins of a medieval tower which defended the road passing under the arch. A mile further on a long line of ruined piers and arches crosses the valley. On some of them the “specus” or water channel, five feet high by three feet wide, was quite perfect. On the road we met frequent groups of the “Contadini” who are infinitely more picturesque and full of color than the slicked up figures usually seen in pictures.[10]

12. The Macs [Jervis McEntee and his wife] and I spent the day sketching at the Arch of Nero.

13. Sketched at the Arch. P.M. walked round the head of the gorge of the Anio—looking out from which, toward the sunset of a fine day, is one of the finest views in the world. Below is the deep gorge with the Anio winding thro’ it. On the left the high ridge crested with the houses and towers of Tivoli—its rich flanks streaming with the “cascatelle” which pour from the arches of Macaenas’ villa. On the right of the valley are olive covered ridges—beyond—the vast expanse and wide horizon of the Campagna—above—the sun, shedding floods of light and color over the whole. Under the light of an hour before sunset when the sun is over the scene, directly in front, words cannot describe the richness and fullness of the light and color on the varied vegetation of the valley and mountain plank, and on the vast aerial plain.[11]

21. Rain. Made oil sketch of Arch of Nero.

This was Gifford’s second international painting trip, following an earlier European tour from 1855 to 1857. On this second expedition, from 1868 to 1869, he expanded his European travels to destinations including Egypt, Syria, Jerusalem, Lebanon, Greece, and Türkiye. Upon his return home, Gifford made larger and more refined paintings based on the sketches of his extensive travels, including two paintings of the Arch of Nero, the largest one by far being the Walters painting.

Sanford Robinson Gifford (American, 1823‒1880), Italian Sketchbook, 1867‒1868, graphite on tan, medium-weight, slightly textured wove paper, 5 × 9 × 7/16 in. (12.7 × 22.9 × 1.1 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Jennie Brownscombe, acc. no. 17.141, p. 71

Sadly, in 1880 at the age of fifty-seven, Gifford died of malarial fever and pneumonia. By this time, he had already received institutional recognition and accolades. He was elected as associate of the National Academy in 1851 and a full Academician in 1854. In 1869, he was elected as one of the thirteen subcommittee members to organize the new Metropolitan Museum of Art and was referred to in 1873 as “our greatest landscape painter” by fellow artist John Ferguson Weir, who was at the time serving as the (first) director of the School of Fine Arts at Yale University.[12] Following his death, the Metropolitan Museum of Art honored Gifford with its first artist’s retrospective, exhibiting 160 paintings, as well as an extensive memorial catalogue that included the entirety of his known works, listing 731 paintings. [13] The memorial catalogue lists five paintings titled “The Arch of Nero at Tivoli.” The smallest three, at the time still in the artist’s estate, were the oil sketches done on site and included in his retrospective exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[14] The larger two, made in his studio upon his return, were in private collections. Below, the five paintings are listed as they were in the memorial catalogue, preceded by their number in the catalogue in bold type, and, for the three sketches shown in the retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, their exhibition number in brackets.

| 512 [41] | A Sketch of the Arch of Nero at Tivoli, From the East | Dated October 12, 1868 | 8 × 13 ½ in. | Owned by the Estate |

| 513 [143] | A Sketch of the Arch of Nero at Tivoli, From the East | Dated October 13, 1868 | 9 ½ × 8 in. | Owned by the Estate |

| 514 [132] | A Sketch of the Arch of Nero at Tivoli, From the West | Dated October 13, 1868 | 8 × 13 ½ in. | Owned by the Estate |

| 572 | The Arch of Nero, Tivoli | Date not known | 41 × 45 in. | Owned by Henry James, Baltimore, MD |

| 688 | The Arch of Nero at Tivoli | Dated 1878‒9 | 18 × 16 in. | Owned by Schuyler Skaats |

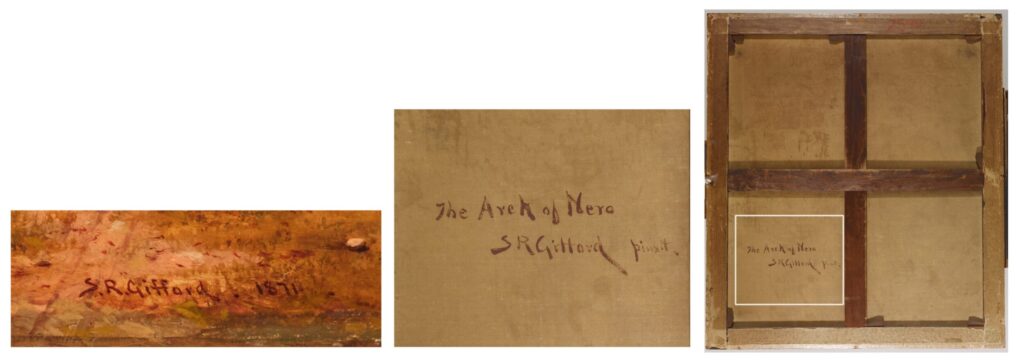

The Walters painting, number 572 in the catalogue, is signed and dated in the bottom left corner in red-brown paint: S.R. Gifford . 1871. On the verso, another inscription by the artist in red-brown paint reads The Arch of Nero/S R Gifford pinxit (fig. 4). It is curious that the date of the Walters painting was listed as “not known” in the catalogue, as it is clearly indicated on the painting, but perhaps that information was not relayed in time for publication by the painting’s first owner. Also, the painting is listed as measuring 41 inches in width and 45 inches in height (the height and the width are denoted in reversed order); however, the painting measures 40 inches in width. The small discrepancy may indicate the original format has changed slightly; however, it is possible that the measurement in the catalogue may have simply been wrong. The latter is most likely true as the dimensions of the two paintings of the arch completed later in the studio compare proportionally; the larger is scaled up 2.5 times the smaller one.[15]

Detail of fig. 1 showing painted signature on front of painting at bottom left (left); detail of written inscription with signature on back of painting (center); back of painting with location of inscription indicated (right)

The painting’s first owner was Henry James, a successful Baltimore businessman who made his fortune in lumber before leading several major corporations, such as the Citizens’ National Bank and Northern Central Railway.[16] He was referred to as “one of the wealthiest of Baltimore citizens” in his obituary in the New York paper The Sun.[17] James purchased The Arch of Nero (no. 572) in New York in 1874 for $1,600, according to a receipt of payment in the Walters archives dated March 2 of that year.[18] There is a record of a visit James made to Gifford’s studio at the Tenth Street Studio Building in New York City (a few weeks before the purchase of The Arch of Nero) in a diary entry written in 1874 by Jervis McEntee (who also had a studio in the same building).[19] James previously may have seen Gifford’s paintings in his hometown of Baltimore. Gifford’s painting Lake Garda was shown at the Maryland Historical Society in 1868,[20] and a local collector, J. (Stricker) Jenkins, who reportedly received visitors to his private house,[21] had two paintings by Gifford in his collection: Lake Garda, Italy (most likely the same painting shown at the Historical Society) and Twilight (Adirondacks).[22]

Haze of Obscurity

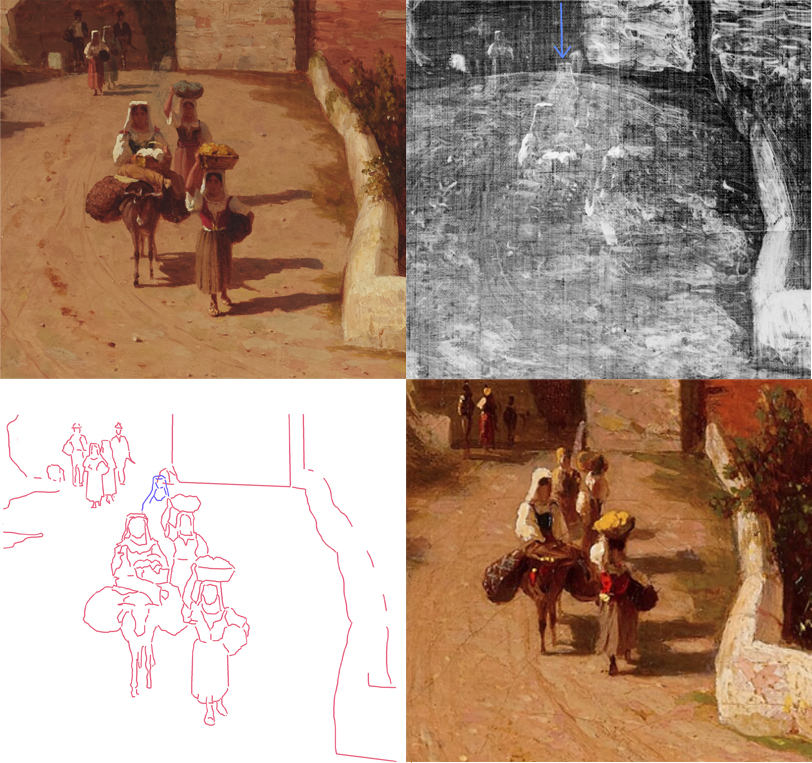

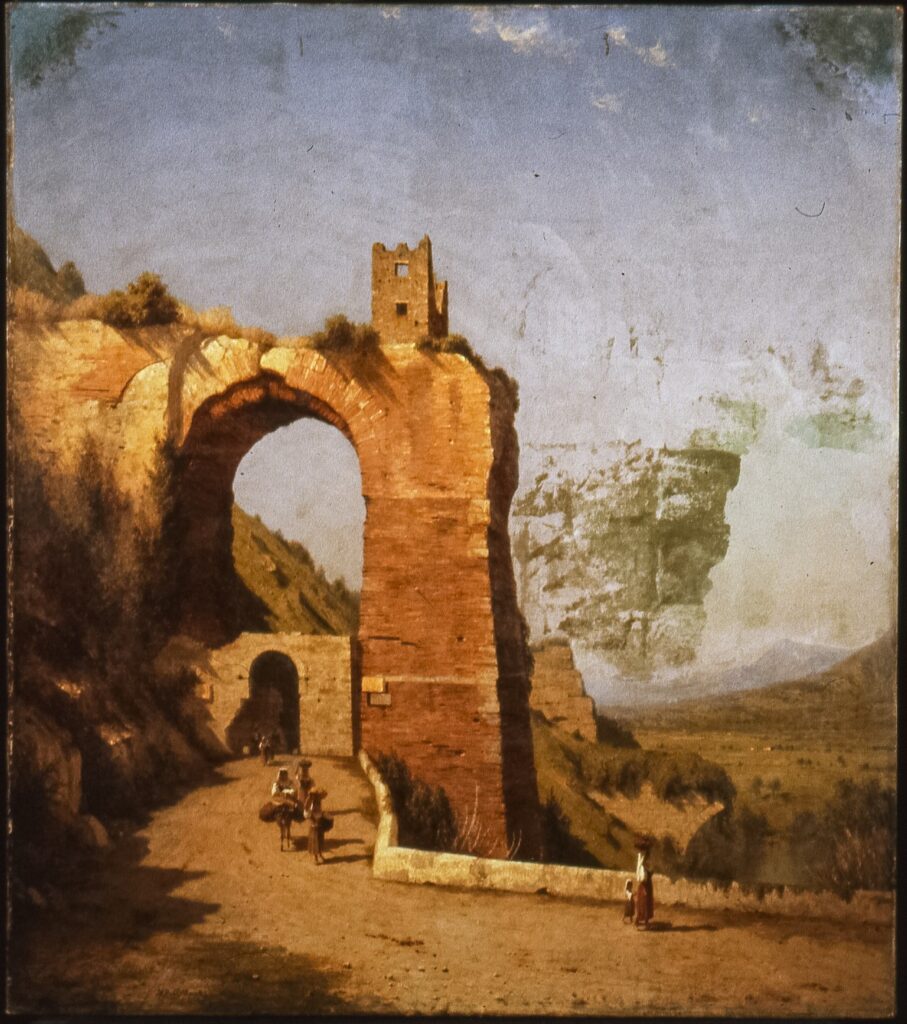

Because the Walters’ painting was out of public view for so long, it was considered lost by scholars until recently. In 1977, when Gifford scholar Ila Weiss published an article featuring Gifford’s 1868 sketchbook, now at the Brooklyn Museum, none of the five painted versions of The Arch of Nero had surfaced publicly, and their locations were unknown to scholars.[23] By 2016, when one of the small painted sketches of the Arch of Nero from Gifford’s trip surfaced on the auction market, A Sketch of the Arch of Nero at Tivoli, From the West, Weiss provided comments on the auction entry: “The present work is the only known surviving example of these [Gifford’s] five paintings depicting Ponte degli Arci.”[24] By 2021, when the smaller studio version originally sold to Schuyler Skaats was offered for sale at Sotheby’s (fig. 5), the Walters’ work seems to have been rediscovered, perhaps due to a dedicated campaign of digitizing the collection at the Walters.[25] Weiss, once again called on for comments, this time mentioned the Walters’ piece in comparison. Though the smaller painting is signed at lower left, SRGifford 1878, and is titled, signed, and dated 1878‒9 (on the reverse), Weiss believed the work at auction to be from the early 1870s “before the completion of The Walter [sic] Art Museum picture.”Weiss states, “Most likely [The Walters Art Museum] piece would have followed [the present work], which was then finished and dated for sale a few years later.”[26] This suggestion, although surprising, is consistent with a finding in the x-ray of the Walters painting that reveals Gifford initially painted but then later covered over an additional female figure at the back of the foreground group that appears in the smaller painting (fig. 6). The Walters’ painting may have followed the smaller studio work, but the larger painting was definitely completed by 1871 (the year it is signed) as it was included in the Brooklyn Art Association’s exhibition in November of that year (see Table 1).

Sanford Robinson Gifford (American, 1823‒1880), The Arch of Nero at Tivoli, 1878, oil on canvas, 8 ⅜ × 16 ⅛ in. (46.6 × 41.1 cm). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s

The obscurity of the Walters’ painting was the reason it was not considered (though its condition at the time would have been too poor) for the major retrospective on his work held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, and the National Gallery of Art in 2003‒2004, Hudson River School Visions: The Landscapes of Sanford R. Gifford. This was the first retrospective of his work in more than thirty years and only the second since his memorial exhibition in 1880. If its location in Baltimore had been known, the organizers of the exhibition (including the nearby National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC) would have requested to come see the painting in person for possible inclusion in the retrospective and/or the accompanying catalogue, especially because Gifford had listed the painting as one of his “chief pictures.”[27]

Detail of fig. 1 showing figures coming out of arch (top left); x-ray detail of same area with blue arrow indicating extra figure taken out in final version (top right); tracing of x-ray detail with extra figure delineated in blue (bottom left); corresponding detail of fig. 5, featuring extra figure (bottom right)

Condition and Treatment

“He [Gifford] recognized in the landscape that its expression, for him, rested mainly in its atmosphere. He rendered this atmosphere palpably, with very subtle sympathy, with great delicacy.”

—John Ferguson Weir[28]

The painting The Arch of Nero (acc. no. 37.2599) entered the collection in 1982 and was noted as needing heavy restoration. Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, 1982

When the painting entered the Walters collection in 1982, it was noted to be “in need of heavy restoration” (fig. 7).[29] The sky, covering approximately two-thirds of the painting, was meant to transition subtly from a deep warm blue at the top to muted pale lavender at the horizon, representing the effects of scattered light, humidity, and temperature, which Gifford referred to as “air painting.”[30] Instead, heavily discolored restoration paint and toned varnish covered much of the sky, ruinous to the intended atmospheric effects at which the artist excelled.

An x-radiograph (x-ray) of the painting taken at the museum in 1982 revealed there was a 2 ½-inch disruption to the original canvas in the sky near the right side just above center, which appeared to be a cut or a tear. Liberally applied restoration paint, appearing more radio-opaque in the x-ray than the original paint layers, extended well past this damage to the left and below toward the horizon line, covering original paint. In the past the painting was glue-lined,[31] likely to repair the 2 ½-inch damage to the original canvas, and the existence of the artist’s inscription on the back of the lining canvas indicates the damage happened early in the painting’s history (before 1880, while the artist was still alive). Before it was sold, Gifford exhibited the painting in at least three venues, increasing the risks for damage during transit and handling (see Table 1).[32] Such damage is confirmed by Willis O. Chapin (supporter and unofficial historian of the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy),[33] who noted that “at the exhibition of 1873 the ‘Arch of Nero,’ by S. R. Gifford, was damaged in unpacking, costing the [Buffalo Fine Arts] Academy $323 in settlement.”[34] This revealing clue to the painting’s history indicates the painting was cut during unpacking at the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy resulting in the 2 ½-inch damage to the canvas seen in the x-ray. The “settlement” was likely an agreement made by Gifford and the Academy that covered Gifford for any damages while the painting was in the custody of the borrower. In this case, it seems that reimbursement was money for restoration work to repair canvas and paint layers costing $323, approximately $8,500 in 2024. No further records detailing repair work have been found to date. This event explains how the artist was able to inscribe the back of the lining canvas once the restored painting was returned to him.[35]

Conservation treatment of the painting at the Walters took place over three major campaigns—with each intervention contributing to returning the painting to Gifford’s original intent. During the course of treatment, Walters conservators discovered that there were at least three separate earlier campaigns of oil paint restoration and evidence of significant damage to original paint layers. These early campaigns likely began with the 1873 settlement in which it is believed the painting was lined to repair the cut canvas and associated disruptions to paint layers. The painting was still relatively new when it was lined, so excessive heat from a hand iron, along with water and pressure used in the glue-lining process, could have easily caused additional damage to the “young” paint layers. Subsequently applied restoration oil paint, applied to cover these damages, could have quickly discolored, prompting further interventions, including early aggressive cleaning attempts and broadly applied repainting.[36]

The Arch of Nero at the end of the treatment campaign in 1982. Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, 1982

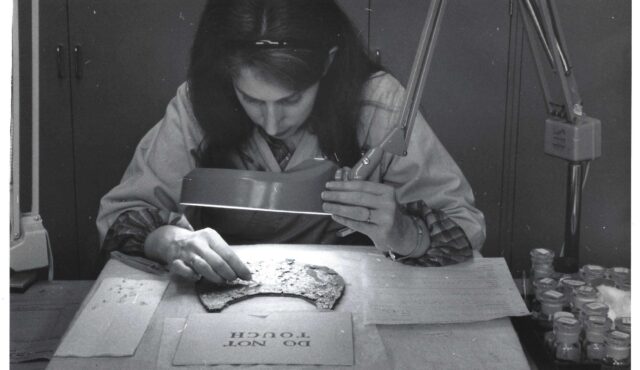

In 1982, a heavily discolored varnish layer was removed from the surface. After various solvents and delivery applications failed to effectively remove restoration overpaint in the sky, the topmost layers of this overpaint were instead removed mechanically with a scalpel blade working under a binocular microscope. Further restoration paint layers remained but were not removed at this time (fig. 8). Evidence of old paint loss was noted below these areas, indicating damage from heat or abrasion to original layers from prior cleaning attempts. During the 1998‒1999 treatment, mechanical removal of darkened overpaint continued with a scalpel blade under the microscope. The successful removal of a discrete greenish-brown layer revealed even more restoration paint below, which still covered a large area of the sky and was inconsistent in texture and color to surrounding paint. A variety of solvents and applications were again tested for overpaint removal, but as nothing was found to be adequately suitable, the treatment was halted (fig. 9).

The Arch of Nero’s condition at the end of the second treatment campaign in 1999 and before the 2020 campaign. Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, 2013

At the start of the most recent conservation treatment from late 2020 to early 2023, the painting retained a slightly smaller but still very disfigured area of discolored greenish overpaint, approximately 10 inches high by 16 inches wide at center right, as well as darkened areas of non-original paint at the top two corners.[37] The remaining overpaint, besides being discolored, was a different texture and uncharacteristic of Gifford’s original paint, which precluded leaving it in place and toning it (fig. 10). Conservators considered the possibility that lower layers of restoration paint may have been added by Gifford after the damage occurred, but the different texture indicated it was most likely added by another hand, probably at the time of lining as part of the “settlement.” To regain a sense of Gifford’s original atmospheric effects, the conservator and the curator of the collection determined the best path forward was to remove, or reduce as much as possible, the remaining accumulation of discolored non-original materials, followed by sensitive reintegration of stains and paint loss.[38] Conservators resumed reducing the overpaint with the use of a customized emulsified water and solvent solution, with materials more recently introduced to the conservation field, in tandem with mechanical cleaning with a scalpel blade under the microscope. Damages, including losses, stains, and abrasion to original paint layers, were then inpainted with conservation-grade materials to bring back the subtle tone and color gradations of the sky.

Detail during the most recent treatment campaign from 2020 to 2023. Photo: Pamela Betts, 2020

Conclusion

After forty years and the efforts of several painting conservators at the Walters, the painting’s aesthetic unity has been restored and we have regained Gifford’s imitation of “the colour of the air.”[39] The final phase of conservation treatment at the Walters relied on innovative techniques, including a custom-tailored water-solvent emulsion, and further benefited from extended periods of uninterrupted focus during the pandemic. The treatment highlights the impact in many ways that the conservation of objects can have on museum collections and artist’s histories; in this instance, treatment clarified the date and timeline of the painting as well as the original dimensions, in addition to elucidating past damage. Once vanished from the consciousness of art historians, The Arch of Nero, considered by Gifford to be one of his “chief pictures,” now rejoins the canon of art history and can finally be enjoyed by Walters visitors.

The Walters Art Museum would like to acknowledge the generosity of museum supporters, including a matching gift from a Walters Trustee, to support the conservation treatment of Sanford Robinson Gifford’s The Arch of Nero on the Walters Art Museum’s inaugural Day of Giving, 2022.

| Date | Title | Venue | Comments | Source |

| May 6, 1871 | Arc (sic) of Nero with figures RS Gifford, entry no. 16 | Century Association Exhibition | n/a | Louis Lang, Art History of the Century Association, 1847‒1880, p. 72, a digitized handwritten record book, accessed January 2024, https://fliphtml5.com/dyine/rhje |

| July 1871 | The Arch of Nero, Sabine Mountains, entry no. 63 | Annual Exhibition of the Yale School of the Fine Arts | n/a | Third Annual Exhibition of the Yale School of the Fine Arts, 1871, p. 5, catalogue, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015074680854&seq=7 |

| November 1871 | The Arch of Nero | Brooklyn Art Association | “Sanford R Gifford, a large and powerful work, the Arch of Nero, the results of his study during his recent European trip; it is very brilliant in color.” | “Brooklyn Art Association / Concluding Article,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 4, 1871, p. 2, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=tbd18711204-01.1.1&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN———- |

| January 1872 | Arch of Nero with Figures, entry no. 34 | The Century Association, NYC | Arch of Nero [undecipherable]with figures SR Gifford, larger picture | Louis Lang, Art History of the Century Association, 1847‒1880, p. 79,accessed January 2024, https://fliphtml5.com/dyine/rhje |

| March 1873 | Arch of Nero—Sabine Mountains, entry no. 128 | Buffalo Academy of Fine Arts | “The Arch of Nero in the Sabian [sic] Mountains by S. Gifford is a bold and effective picture. The artist has evidently made a faithful transcript of the scene, confident that the ruined arch and the broken bridge nearby required no romantic investiture at his hands. The coloring is very fine, and the distant landscape is evidently true to nature.” Although this comment doesn’t prove it was the larger painting, we know the damage happened at this venue. | Buffalo Courier, March 13, 1873, p. 2 |

| September 3‒October 4, 1873 | The Arch of Nero, entry no. 210 | Cincinnati Industrial Exposition | “A road passes through a great ruined archway built by the Romans to last for ages, whose somber red brick-work contrasts strongly with the gray stone mediaeval tower perched on its top. Peasant women, scarlet-robed and white-coifed, on donkeys, or with bundles gracefully poised on the head, symbolize the present time in this union of three different ages of the world.” | Exhibition of Paintings, Engravings, Drawings, Aquarelles, and Works of Household Art in the Cincinnati Industrial Exposition,1873, p. 26 |

Exhibition of Painting(s) by Gifford Titled Arch of Nero, 1871‒1873

(the highlighted are those confirmed to be of the Walters piece)

[1] The name changed to the Walters Art Museum in 2000.

[2] Gifford enclosed “A List of Some of My Chief Pictures” in a November 6, 1874, letter to clergyman and writer Octavius Brooks Frothingham, a transcript of which is reprinted in Ila Weiss, Poetic Landscape, The Art and Experience of Sanford R. Gifford (University of Delaware Press, 1987), Appendix B, 327‒30.

[3] The ruin is still extant, although the smaller interior arch from which several figures are traveling no longer exists; presumably it was removed to widen the road.

[4] For other artists who visited the site, see Marcel Roethlisberger, “Darstellungen einer tiburtinischen Ruine,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 48, no. 3 (1985): 300–18.

[5] Handwritten letter dated November 6, 1874, accessed from the Sanford Robinson Gifford papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Box 1, Folder 4: Loose letters, 1856, 1869, 1879.

[6] Acc. no. 17.141. The sketchbook spans June through October of 1868; sketches of the arch are on pages 70, 71, and 73.

[7] See sketch to the right edge of page 71.

[8] Sanford Robinson Gifford papers, 1840s‒1900, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Biographical note accessed January 22, 2024.

[9] One is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and one was previously at the Newark Museum but was sold to a foundation and is currently on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

[10] Sanford Robinson Gifford papers, 1840s‒1900, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Box 1, Folder 3: European Letters, Volume III, June 1868‒August 1869, pp. 48, 49, 51.

[11] His walk to Tivoli was approximately 1.5‒2 miles west and north from the arch.

[12] John Ferguson Weir, “American Landscape Painters,” The New Englander, 32, no. 122 (January 1873):140‒151, at 147.

[13] The 160 paintings in the retrospective exhibition are listed in Metropolitan Museum of Art: Handbook No. 6, Loan Collection of Paintings in the West and East Galleries, October 1880 to March 1881, published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see images 48–54 at https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/sanford-robinson-gifford-papers-8974/series-2/box-2-folder-1); the 731 paintings in the memorial catalogue are listed in A Memorial Catalogue of the Paintings of Sanford Robinson Gifford, N. A., with a Biographical and Critical Essay by Prof. John F. Weir, published under the auspices of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1881, https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15324coll10/id/9460, accessed 11/5/2020).

[14] The two painted sketches of the arch viewed from the east are currently unlocated. The Walters painting is also viewed from the east.

[15] The original tacking edges are no longer extant on the Walters painting. Evidence of scalloped canvas threads along the edges of the canvas (created when the canvas is initially stretched and mounted to an auxiliary support, which can cause slight deformation of the weave structure around the edges) is not seen. However, the artist may have purchased commercially prepared canvas, which would not necessarily show this feature and thus preclude its absence as an indication of lost material.

[16] See Henry James’s obituary, The Baltimore Sun, July 28, 1897, 8.

[17] The Sun (New York), July 28, 1897, 3.

[18] The painting was bequeathed to the Walters Art Museum by Henry James’s granddaughter Priscilla Ridgely Schaff (daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Harry White, nee Bertha James, who was the daughter of Henry James). Receipt states: Henry James Esq. to SR Gifford for picture called ‘The Arch of Nero’ (with frame) $1604 (including $4 for boxing, etc). The Walters Art Museum Archives, Baltimore.

[19] “Thursday, Feb. 17. Mr. Holt came this morning with Mr. and Mrs. James and another lady. They all seemed to like my November best but didn’t buy. They went from here to Gifford’s room and I am quite sure his pictures will please them better than mine.” “Jervis McEntee’s Diary,” Archives of American Art Journal 8, no. 3/4 (1968): 1‒29, 32, at 25.

[20] Kevin J. Avery and Franklin Kelly, Hudson River School Visions: The Landscapes of Sanford R. Gifford (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003), 251. (The chronology compiled by Claire A. Conway and Alicia Ruggiero Bochi lists it as Lake of Garda, possibly in the collection of J. Stricker Jenkins by this time.)

[21] Carol Strohecker, The Taste of Maryland: Art Collecting in Maryland, 1800‒1934 (Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 1984), 22.

[22] These reflect the titles used in the 1876 auction catalogue of Jenkins’s paintings: George A. Leavitt & Co, Catalogue of Valuable Paintings: The Private Collection of Mr. J. Stricker Jenkins of Baltimore, MD., Comprising Choice Examples of American and Foreign Art (unpaginated). In an attendee’s annotated copy of the sale catalogue in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s library (https://archive.org/details/b1469342, accessed October 28, 2024), Lake Garda, Italy is listed as entry no. 32 and was sold to DH McAlpin, 20 W. 52nd St. for $300; Twilight (Adirondacks), no. 87, was sold to LA Lanthier, 6 Astor Place for $400. According to the chronology section in Hudson River School Visions, in 1870 Gifford’s paintings titled Riva, Lake Garda and Twilight in the Adirondack Mountains were shown “at the Jenkins Collection at the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore” (251). This unfortunately was not cited and is slightly problematic, partly because Walters Art Gallery did not exist as an institution at this time and because Gifford painted several versions of these paintings—at least four versions of Twilight in the Adirondack Mountains and at least two of Lake Garda; however, it strongly indicates that Stricker did own the two Gifford paintings listed in his 1876 auction catalogue by 1870.

[23] Ila Weiss, “Sanford R. Gifford in Europe: A Sketchbook of 1868,” The American Art Journal 9, no. 2 (November 1977): 83‒103; Ila Weiss, “Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823–1888)” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1968).

[24] Bonhams, American Art, November 22, 2016, New York, Lot 19, https://www.bonhams.com/auction/23480/lot/19/sanford-robinson-gifford-1823-1880-arch-of-nero-at-tivoli-from-the-west-8-x-13-38in/, accessed February 23, 2021.

[25] The treatment was not finalized until 2023, but some images were added to the website during the course of treatment.

[26] Sotheby’s, Two Centuries: American Art, October 6, 2021, New York, Lot 22, https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/two-centuries-american-art-2/the-arch-of-nero-at-tivoli?locale=en.

[27] This was confirmed by Franklin Kelly, the Christiane Ellis Valone Curator of American Paintings at the National Gallery of Art, who was a co-organizer of the exhibition and at the time was titled Senior Curator of American and British paintings at the National Gallery of Art.

[28] Extract from an address by American artist Weir (1841‒1926), the first director of the School of Fine Arts at Yale University, presented to the Century Association, November 19, 1880. The address, “Sanford R. Gifford: His Life and Character as Artist and Man,” is included in Sanford Gifford’s memorial catalogue. See Memorial Catalogue, 9‒10.

[29] A handwritten note on the Mercantile-Safe Deposit and Trust Company Corporation Release (representing the estate of Priscilla Ridgely Schaff), likely by the Walters Registrar Leopoldine H. Arz, states, “In need of heavy restoration.” Document dated May 26, 1982.

[30] “With Mr. Gifford landscape-painting is air-painting.” George William Sheldon, “How One Landscape Painter Paints,” Art Journal 3 (1877): 284. Sheldon’s use of quotation marks likely indicates direct quotes from his interviews with the artist (see Avery and Kelly, Hudson River School Visions, 17).

[31] A restoration campaign in which a secondary canvas is glued to the back of the original canvas with a water-based adhesive and the use of heat (in early days, with a hand iron). This was often done to support a damaged or otherwise compromised canvas. The original tacking edges were removed at this time.

[32] Before the painting was sold to James, the Arch of Nero now at the Walters was included in at least three exhibitions. There are three other exhibitions that included Gifford’s Arch of Nero before the sale date, and though he presumably preferred to send out his larger “presentation” piece for public viewing, it is difficult to confirm which version is meant in these instances.

[33] Shannon N. Gilmartin, “Lars Gustaf Sellstedt: Art in Buffalo and the Buffalo Fine Art Academy” (master’s thesis, Buffalo State College, 2023), 4, https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/history_theses/60.

[34] Willis O. Chapin, The Buffalo Fine Arts Academy: A Historical Sketch, 1899, 40. The damage was also reported in Buffalo newspapers: Buffalo Courier, January 8, 1874 (reported it cost $325) and Buffalo Post, January 8, 1874 ($323).

[35] Signing or inscribing the backs of his paintings was seemingly not uncommon for Gifford to do, as several examples exist, but most of his paintings were not lined during his lifetime, so his writing on the back of the Walters’ lined painting is highly unusual. At this time it is not known if the back of the original canvas, now hidden by the lining canvas, was also signed—this possibility could be further investigated in the future.

[36] The repairs must have been undertaken quickly and well enough disguised as to merit the following comment in the newspaper from the Buffalo Academy: “The arch of Nero in the Sabian [sic] mountains by S. Gifford is a bold and effective picture. The artist has evidently made a faithful transcript to the scene, confident that the ruined arch and the broken bridge near by required no romantic investiture at his hands. The coloring is very fine, and the distant landscape is evidently true to nature; and if this and the picture previously referred to [a landscape by Casilear] were made the property of the Academy, we should consider the accession very valuable (Buffalo Courier, “The Fine Arts Academy. Grand Art Reunion—Some of the Pictures,” March 13, 1873).

[37] The top two corners of the painting were also covered with discolored restoration paint, hiding abrasion to paint layers possibly caused by past use of a (lost) frame with a liner with curved spandrels at top. There is no longer an early or original frame associated with the painting, and the incoming receipt to the Walters does not mention a frame. A handwritten note on an index card for the painting in the registrar’s archives, likely from the 1980s, lists a one-time location for an associated frame; however, thorough recent searches have failed to locate this.

[38] Reintegration of stains and paint losses is done with locally applied inpainting using reversible conservation materials.

[39] Sheldon, “Landscape Painter,” 284 (referring to Gifford’s paintings).