The Walters Art Museum includes within its collection twelve Ethiopian copper-alloy crosses, dating from between the twelfth and twentieth centuries. Eight of these feature what appears to be intentionally applied black material in the engraved designs and punchwork. In advance of the 2023‒2024 exhibition Ethiopia at the Crossroads, these crosses and related historic metalwork from Ethiopian lands were the subject of a technical study that described the presence and appearance of this black material.[1] This black material has only recently been noted in the literature,[2] but until now it has not been subject to analysis nor has its significance been adequately evaluated.

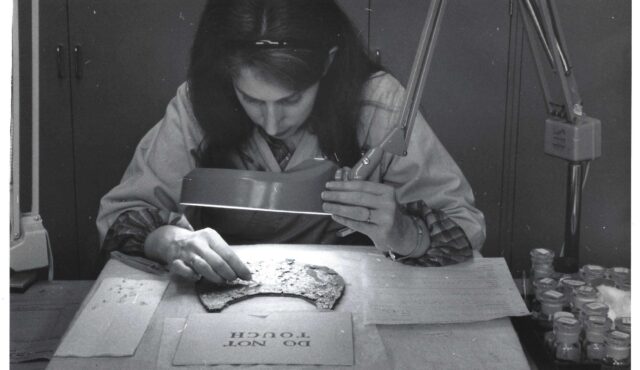

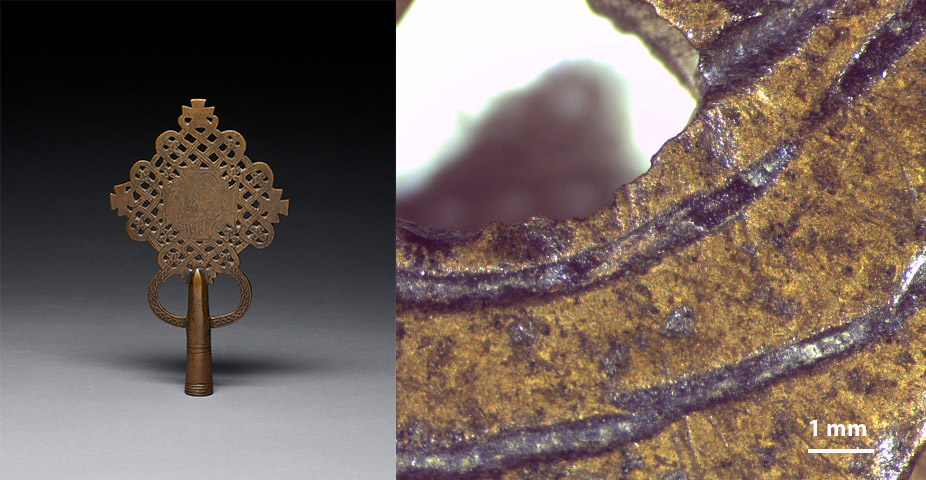

Processional cross with detail of engraved lines filled with black material

Unidentified artist, Processional Cross, Ethiopia, 15th century, copper alloy, 9 1/4 × 5 11/16 × 29/32 in. (23.9 × 14.4 × 2.3 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 1996, acc. no. 54.2892

Under binocular magnification, the black material applied to the engraved and punched decoration of the Walters crosses appears somewhat glossy, often features a network of cracks, and is frequently sunken below the surface of the metal, suggesting it was applied as a slurry or paste that was wiped away from the surface before drying or setting (fig. 1).[3] The visual similarity of this applied black material on historic Ethiopian Orthodox copper-alloy crosses to black materials on contemporaneous inlaid Islamic metalwork has previously been noted, though the significance of this observation was not clear.[4] The current study aims to characterize the black material on six of the Walters crosses through a multi-analytical approach and to assess potential connections to materials and techniques employed in Islamic inlaid metalwork.

Methods

To better characterize the composition of applied black material and other materials that may be present within stratified layers, samples were taken from six processional crosses, ranging from roughly the twelfth to fifteenth centuries (Table 1, Summary of Analysis of Crosses Grouped by Date). Individual samples were further divided and each was subjected to analysis by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography‒Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC-MS).[5]

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Samples were analyzed by FTIR microspectroscopy, an instrumental technique that permits the general classification of natural organic materials (such as waxes, proteins, oils, polysaccharides, and resins) and the more specific identification of synthetic resins, inorganic pigments, and natural minerals. Sample material was acquired with a stainless-steel scalpel and the aid of a stereomicroscope and then placed directly on a diamond cell. The material was rolled flat on the diamond compression cell with a steel micro-roller to decrease thickness and increase transparency. The sample was analyzed using the Thermo Scientific Nicolet 6700 FTIR with Nicolet Continuμm FTIR microscope (transmission mode); data was acquired for 128 scans from 4000 to 650 cm-1 at a spectral resolution of 4 cm-1. Multiple scrapings of the sample were taken from the bulk sample, and multiple spectra were taken from different areas within each scraping. Spectra were collected with Omnic 8.0 software and analyzed in this program with various Infrared and Raman Users Group (IRUG) Spectral Database and commercial reference spectral libraries.

Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography‒Mass Spectrometry (py-GC-MS)

Samples were also analyzed by py-GC-MS. This technique is best suited to the identification of polymeric and composite materials. Samples were analyzed using the Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph equipped with an Agilent 5977A mass selective detector (MSD) and a 7693 Autosampler. The Agilent Mass Hunter Software was used for analysis.

Samples suspected of containing oils, resins, and waxes are often composed, in part, of carboxylic acids or esters. To reduce the molecular weight and make the components more volatile, the samples are treated with a MethPrep II reagent that converts carboxylic acids and esters to their methyl ester derivatives. Samples were placed in tightly capped vials (100‒300 μL), and approximately 100 mL (or less for a smaller sample) of 1:2 MethPrep II reagent (TCI) in toluene were added. The vials were warmed at 60oC for one hour in the heating block, removed from heat, and allowed to stand to cool. Analysis was carried out using the Winterthur RTLMPREP method,[6] with conditions as follows: the inlet temperature was 300°C and transfer line temperature to the MSD (SCAN mode) was 300°C. A sample volume (splitless) of 1 µL was injected onto a 30m×250µm×0.25µm film thickness HP-5MS column (5% phenyl methyl siloxane at a flow rate of 2.3 mL/minute). The oven temperature was held at 55°C for two minutes, then programmed to increase at 10°C/minute to 325°C where it was held for 10.5 minutes for a total run time of 40 minutes. A 9.5 minute solvent delay was used.[7]

Samples suspected of containing carbohydrate materials were treated with approximately 100 μL of 0.5M solution of HCl in methanol at 60oC for 24 hours in a tightly capped vial (100‒300 μL). (The 0.5M HCl/methanol solution, which is stable in a refrigerator for about two weeks, is prepared fresh for the day’s work by adding 0.4 mL of acetyl chloride with an Eppendorf pipette to 15 mL of anhydrous methanol and stirring.) The digested sample solution was evaporated to dryness in a stream of N2. After the addition of 50 µL (or less for small samples) of BSTFA – Bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetaminde), the vial(s) were warmed at 60oC for one hour in the heating block, removed from heat, and allowed to stand to cool. Analysis was carried out using the Winterthur RTLGUMS method,[8] with conditions as follows: inlet temperature was 300°C and transfer line temperature to the MSD (SCAN mode) was 300°C. A sample volume (splitless) of 1 µL was injected onto a 30m × 250µm × 0.25µm film thickness HP-5MS column (5% phenyl methyl siloxane) at a flow rate of 2.0mL/minute). The oven temperature was set at 55oC for 1.5 minutes and then increased at 50oC/minute to 150°C, and increased again at 2°C/minute to 200°C, followed by a final increase at 20oC/minute to 300oC, where it was held for five minutes for a total run time of 38.15 minutes.

Results

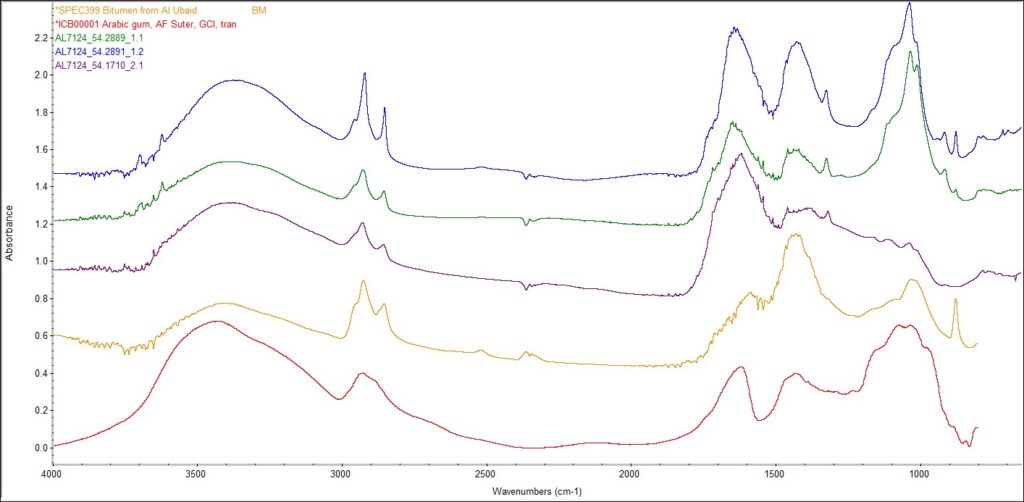

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Bitumen and/or gum arabic were identified in samples from five of six crosses analyzed (acc. nos. 54.1710, 54.2889, 54.2890, 54.2891, 54.2894). Bitumen and gum arabic share similar peaks, making precise identification of the two materials difficult using this technique (fig. 2).

FTIR analysis of samples from crosses 54.2889, 54.2891, and 54.1710 compared to reference spectra of bitumen and gum arabic

Iron oxides were identified in two of the samples analyzed (acc. nos. 54.2889, 54.2892). These may be attributable to an admixture of dirt or earth pigments such as ochre.

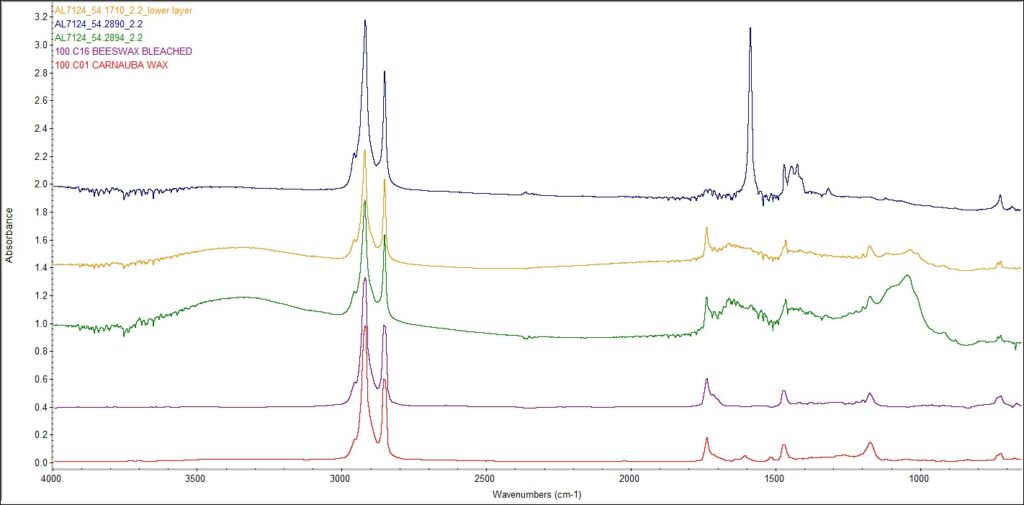

FTIR analysis of lower layers of samples from crosses 54.1710, 54.2890, and 54.2894 compared to reference spectra of waxes

Waxes were identified in three of the samples analyzed (acc. nos. 54.1710, 54.2890, 54.2894). The portions in which wax was identified were taken from the lower layers of each sample, indicating the wax was applied to the surface prior to the black material.[9] Identification of the specific type of wax employed is difficult; however, similarities to reference spectra for beeswax and carnauba were noted (fig. 3)

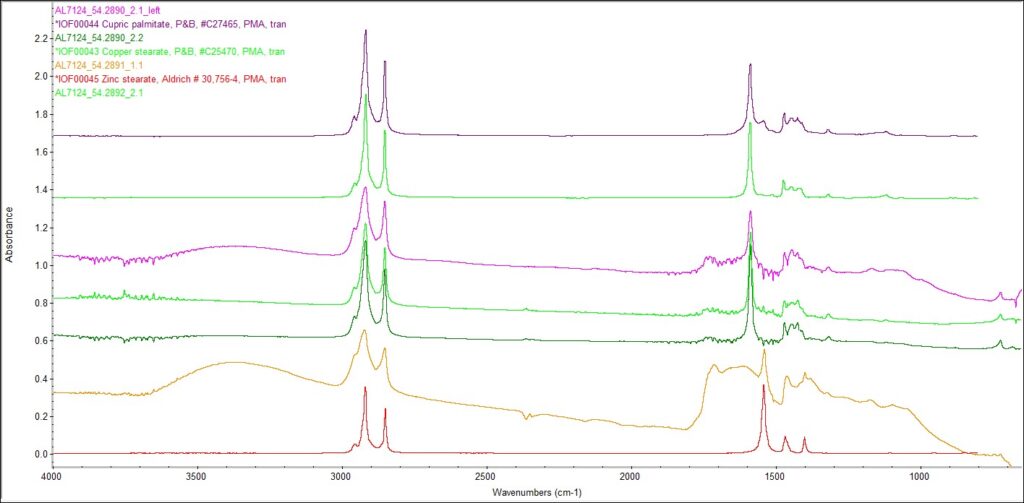

FTIR analysis of samples from crosses 54.2890, 54.2891, and 54.2892 compared to reference spectra of metal soaps copper stearate, cupric palmitate, and zinc stearate

Metal soaps (copper stearate, cupric palmitate, and zinc stearate) were identified in three of the samples analyzed (acc. nos. 54.2890, 54.2891, 54.2892) (fig. 4). Stearates and palmitates are common deterioration products of oils and waxes, and they will readily form metallic soaps when in contact with copper-alloy surfaces such as those on these crosses.[10]

Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography‒Mass Spectrometry (py-GC-MS)

All six samples contained beeswax, with the sample from acc. no. 54.2894 clearly showing all markers for beeswax (C-24 prominences, hydrocarbon pattern, and palmitic ester of fatty alcohols). Five of the samples (acc. nos. 54.1710, 54.2889, 54.2890, 54.2891, 54.2892) also included indications of non-drying oils, with very little azelaic acid detected.

None of the samples contained carbohydrates. GC-MS did not confirm the identification of gum arabic in instances where FTIR had peaks that could be interpreted as either gum arabic or bitumen.

Samples from three of the crosses (acc. nos. 54.1710, 54.2891, 54.2892) had trace amounts of cholesterol oxidation products, including stearic and palmitic acids. As noted above, these may be deterioration products from oils and waxes, or they may also result from repeated handling.

Discussion

Taken together, the results of FTIR and py-GC-MS analysis of samples of black material from these six crosses show traces of beeswax or its deterioration products in the underlayers closest to the metal surfaces. There are further indications of non-drying oils[11] and possibly some iron containing earth materials in the upper layers. No carbohydrates were conclusively identified in any samples by py-GC-MS, suggesting that FTIR results for five of these samples (acc. nos. 54.1710, 54.2889, 54.2890, 54.2891, 54.2894) may best be interpreted as identifying bitumen.

The presence of markers for wax in the layers of black material closest to the surfaces of these copper-alloy crosses strongly suggests that the crosses were waxed after casting and finishing. Wax coatings have been used for bronze and copper-alloy objects since antiquity, both as a protective coating and as an aesthetic enhancement for their lustrous surfaces,[12] though research has shown that wax coatings are not especially effective at preventing corrosion and begin to break down quickly.[13] All of the crosses included in this study were created by the lost-wax casting process,[14] which traditionally relies upon beeswax. Given that substantial amounts of this familiar material would have been available to the craftspeople or workshops manufacturing these crosses, it is perhaps not surprising that it may have been employed as a surface finish as well.

The identification of bitumen argues in favor of the theory that the black material on these crosses is an intentional application rather than merely accumulated dirt or residues, as bitumen has no known ritual or liturgical significance within the Ethiopian context.[15] The presence of bitumen-containing black material over the wax indicates that it was applied in the final stages of finishing these crosses or at some later date. This intentional finishing step of applying black bituminous material to the lightly engraved and punched decoration originally would have dramatically enhanced the decoration’s legibility against the bright golden tones of the copper-alloy crosses, recalling the contrasts of black material applied to engraved and inlaid copper-alloy Islamic metalwork.

Inlaid metalwork created throughout Islamic North Africa, the Levant, and Central Asia from the twelfth century onward spans a variety of forms and functions, both secular and religious. Though examples in precious metals are known, the majority of such metalwork was constructed of copper alloy, customarily inlaid and overlaid with silver, copper, or gold. Contrasts among these materials were heightened and design motifs strengthened by the application of black materials to the engraved and punched recesses, typically composed of preparations including bitumen.[16]

Medieval Christian Ethiopia maintained strong religious, diplomatic, and economic ties to lands under Muslim control, particularly Egypt and the cities of Cairo and Alexandria, offering myriad avenues for artistic and material exchange via diplomatic envoys, pilgrimages, and trade, especially during the era of the Mamluk empire (1250‒1517).[17] Following the upheavals of the Mongol invasions of the fourteenth century, many skilled metalworkers from the Levant and Central Asia relocated to Cairo, where the practice of inlaid metalwork flourished.[18]

Inlaid Islamic metalwork was highly valued and frequently employed in liturgical contexts in medieval Ethiopia, as evidenced by the relatively large number of such objects that remain in church treasuries or have been recovered from archeological contexts in religious settings.[19] In particular, salvers, trays, and stands of Egyptian inlaid metalwork, produced mainly in Cairo for secular purposes, seem to have been especially prized by medieval clergy at Lalibäla, where a number of examples in the treasuries of the churches of Saints Mary, George, and Mercurius are datable to the thirteenth‒fifteenth centuries on the basis of their inscriptions.[20] The secular Islamic origins of these items, often featuring prominent inscriptions in Arabic, seem to have offered no impediment to their adoption for Christian liturgical use. Indeed, they may reflect the broader cosmopolitan appeal of imported luxury materials such as Indian and Persian textiles,[21] French and Italian paintings and enamels,[22] and Chinese porcelains valued by the Ethiopian imperial elite and often repurposed or incorporated into Christian contexts.[23]

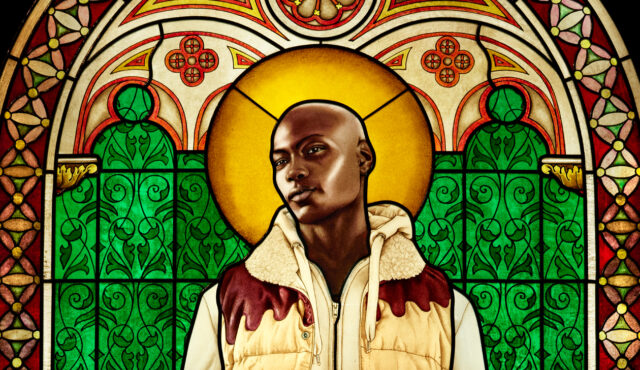

The silver inlay interlace patterns on this Islamic salver are similar to the pierced and incised decoration on the processional cross, acc. no. 54.2892 (fig. 1), and both date to the 15th century.

Mahmud ibn al-Kurdi, Salver, Iran, late 15th century, brass, gilded and inlaid with silver, H: 2 1/4 × Diam: 19 1/2 in. (5.7 × 49.5 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, 1927, acc. no. 54.527

Ethiopians held inlaid Islamic metalwork in such high esteem that its style influenced local production of liturgical objects—for example, a brass paten in the treasury of the church of ‘Ura Mäsqäl (‘Ura Qirqos) in ‘Addigrat, which employs motifs and heraldic emblems frequently found on inlaid Mamluk metalwork produced in Cairo.[24] Later Mamluk metalwork of the fifteenth‒sixteenth centuries relied heavily on interlace motifs, especially wares destined for export,[25] often resembling the dense patterns of interlace found on Ethiopian crosses of a similar period. For example, the silver inlay interlace pattern on an Islamic salver in the Walters Art Museum (fig. 5) may be compared to the incised decoration on an Ethiopian processional cross (fig. 1), both dating from the fifteenth century.[26]

Mamluk metalwork was also exported to the Rasulid rulers of Yemen during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and there seems to have been local Yemeni production of engraved metalwork during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.[27] Though these works have yet to receive systematic study, it appears that at least some of the later engraved Yemeni metalwork is also enhanced with applied black material.[28] Given the long history of trade and communication between Yemen and the immediately adjacent Ethiopian lands,[29] Yemeni metalwork practices influenced by earlier Mamluk metalwork may offer yet another source of inspiration or point of connection for Ethiopian craftspeople, including those in the southern sultanates of Ifat (1285‒1415) and ‘Adal (1415‒1577).

In this context of material and artistic exchange, it is likely that the contrasting inlaid and overlaid surfaces of Mamluk metalwork inspired Ethiopian craftspeople to adopt and adapt other features of production beyond stylistic motifs. One example worthy of consideration is the so-called “King Lalibäla cross,” datable to the thirteenth century and still in service at the royal tomb in the Church of Betä Golgotha, featuring an unusual but arresting pattern of copper and copper-alloy concentric circles inlaid into an iron cross body. Another cross, made ca. 1500 and now in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (acc. no. 1999.103), is constructed of wood inlaid with tin and other materials. It is attributed to a craftsman of the Stephanite monastic order known as Ezra (1460‒1522) who is thought to have learned techniques of inlay and marquetry while in Egypt.[30]

While these may represent rather unusual experiments in metal inlay potentially inspired by Mamluk metalwork,[31] the identification of bituminous black material on five crosses within the Walters’ own collection suggests that the practice of applying this material to copper-alloy crosses may have been much more widespread. The application of bituminous black material to heighten the contrast of engraved or recessed designs on bright copper-alloy surfaces can now be identified as a shared feature of both Mamluk metalwork and Ethiopian Orthodox crosses of the twelfth‒fifteenth centuries, a consequence of complex networks of exchange between the two cultures.

Conclusion

Examination and scientific analysis by FTIR and py-GC-MS of samples of applied black material on six crosses in the Walters collection dating from the twelfth‒fifteenth centuries suggests beeswax was applied as a likely original finish. Additionally, for five of the samples, bitumen was identified as a component of the black material, similar to previously published compositions of visually similar black material on contemporaneous Islamic metalwork manufactured in Mamluk lands and elsewhere.

Based on surviving evidence, Islamic inlaid metalwork was prized in Ethiopian royal religious contexts and seems to have inspired at least some craftspeople working in Ethiopian lands to experiment with motifs and techniques of manufacture inspired by the imported works. Thriving networks of religious, diplomatic, and commercial exchange around the Red Sea and beyond offered myriad potential points of contact between Ethiopian craftspeople and those who created inlaid and engraved Islamic metalwork, raising the possibility of direct transfer of knowledge around materials and techniques as well.

Further study and comparison of black material applied to Ethiopian Orthodox metalwork, especially that of later periods, is much to be desired. The utilization of further analytical techniques, including proteomic approaches and matrix-assisted laser desorption / time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI/TOF) may yield additional information relevant to interpreting the significance of this black material and its relation to metalworking practices in the Islamic world.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere thanks to Christine Sciacca, Curator of European Art, 300‒1400 CE, for her continued interest in Ethiopian material culture and its technical study, as well as Julie Lauffenburger, Conservator Emerita and former Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director of Conservation, Collections, and Technical Research, for facilitating the current analysis and study of these objects.

| Object Information | Dimensions* | Construction | FTIR Results | GC-MS Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54.2889 Processional Cross 12th–13th century | Overall: 13 3/4 × 6 1/4 × 1 7/64 in. (34.9 × 15.7 × 2.8 cm); average thickness of cross body: 5/16 in. (0.8 cm) | Copper alloy | • Bitumen and/or gum arabic • Iron oxides | • Non-drying oils • Some indication of beeswax • No carbohydrates | |

| 54.2891 Processional Cross 12th–13th century | Overall: 10 × 7 9/16 × 29/32 in. (25.5 × 16.1 × 2.3 cm); average thickness of cross body: 5/16 in. (0.8 cm) | Brass | • Bitumen and/or gum arabic • Metal soaps (copper stearate, cupric palmitate, and zinc stearate) | • Non-drying oils • Some indication of beeswax • Cholesterol oxidation products (palmitic and stearic acid), likely resulting from handling • No carbohydrates | |

| 54.1710 Processional Cross 14th–15th century | Overall: 8 3/4 × 4 1/2 × 7/64 in. (22.2 × 11.5 × 2.7 cm); average thickness of cross body: 1/64 in. (0.4 cm) | Copper | • Bitumen and/or gum arabic • Waxes (likely beeswax) | • Non-drying oils • Some indication of beeswax • Cholesterol oxidation products (palmitic and stearic acid), likely resulting from handling • No carbohydrates | |

| 54.2890 Processional Cross 14th–15th century | Overall: 8 55/64 × 6 59/64 × 45/64 in. (22.5 × 17.6 × 1.8 cm); average thickness of cross body: 1/8 in. (0.3 cm) | Bronze | • Bitumen and/or gum arabic • Waxes (likely beeswax) • Metal soaps (copper stearate, cupric palmitate, and zinc stearate) | • Non-drying oils • Some indication of beeswax • No carbohydrates | |

| 54.2892 Processional Cross 15th century | Overall: 9 1/4 × 5 11/16 × 29/32 in. (23.9 × 14.4 × 2.3 cm); average thickness of cross body: 5/32 in. (0.4 cm) | Copper alloy | • Iron oxides • Metal soaps (copper stearate, cupric palmitate, and zinc stearate) | • Non-drying oils • Some indication of beeswax • Cholesterol oxidation products (palmitic and stearic acid), likely resulting from handling • No carbohydrates | |

| 54.2894 Processional Cross 15th century | Overall: 7 7/8 × 5 29/32 × 25/32 in. (26 × 15.9 × 2 cm); average thickness of cross body: 5/32 in. (0.4 cm) | Copper alloy | • Bitumen and/or gum arabic • Waxes (likely beeswax) | • Beeswax—showed all markers (C-24 prominences, hydrocarbon pattern, and palimitic ester of fatty alcohols) • No carbohydrates |

Summary of Analysis of Crosses Grouped by Date

* Overall dimensions of the object are followed by an average thickness of the main body of the cross. Multiple measurements were taken from accessible points using digital calipers, and a representative measurement is reported.

[1] Gregory Bailey, Angela Elliott, and Annette S. Ortiz Miranda, “Analysis and Technical Study of Historic Ethiopian Metalwork and Aksumite Coins at the Walters Art Museum,” in Ethiopia at the Crossroads, ed. Christine Sciacca (Walters Art Museum in Association with Yale University Press, 2023), 161‒69.

[2] Ainslie Harrison, “Technical Study of Ethiopian Copper Alloy Processional Crosses Using Non-Destructive Analysis,” Studies in Conservation 67, no. 7 (2021): 459‒71.

[3] Bailey et al., “Ethiopian Metalwork and Aksumite Coins.”

[4] Bailey et al., “Ethiopian Metalwork and Aksumite Coins.”

[5] Preparation and analysis of samples by FTIR was performed by Katharine Shulman, at the time Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation Graduate Intern in Objects Conservation at the Walters Art Museum, assisted by Patricia Gonzales Gil, Volunteer Scientist at Winterthur Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory; preparation and analysis of samples by py-GC-MS was performed by Chris Petersen, Volunteer Scientist at Winterthur Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory.

[6] RTLMPREP is the Winterthur Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory shorthand for the conditions of the method profile outlined in this methodology. It stands for Retention Time Locked MethPREP. MethPrep is the reagent added to the sample being run.

[7] A 9.5 minute solvent delay is used to let non-essential solvent and excess reagents elute from the column before the mass spectrometer is turned on, saving wear and tear on the instrument. GC-MS is ideal for detecting trace amounts of materials and if the solvent and reagents are not eluted, they would overload the detector unnecessarily.

[8] RTLGUMS is the shorthand for the conditions of the method profile used for identification of carbohydrates (which include gums). It stands for Retention Time Locked Gums.

[9] It should be noted that some of the crosses from which these samples were taken have modern wax coatings on their surfaces; analysis of the lowermost layers was undertaken in order to avoid the potential of any contamination from these later coatings.

[10] For alloy compositions of these crosses as reported by semi-quantitative x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF), see Bailey et al., “Ethiopian Metalwork and Aksumite Coins.”

[11] Though the nature of these oils cannot be determined with these analytical techniques, it is worth noting that liturgical objects are sometimes anointed with oils in Ethiopian Orthodox practice. See Daniel SeifeMichael Feleke, “A Glossary on the Liturgy and Practice of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwaḥədo Church,” in Sciacca, Ethiopia at the Crossroads, 59.

[12] David Scott, Copper and Bronze in Art: Corrosion, Colorants, and Conservation (Getty Conservation Institute, 2002), 382.

[13] Natasja Swartz and Tami Lasseter Clare, “On the Protective Nature of Wax Coatings for Culturally Significant Outdoor Metalworks: Microstructural Flaws, Oxidative Changes, and Barrier Properties,” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 54, no. 3 (2015): 181–20.

[14] Bailey et al., “Ethiopian Metalwork and Aksumite Coins.”

[15] While candles, lamps, incense, and oils have liturgical or ritual significance in Ethiopia, bitumen is not known to be used in any practices associated with processional crosses. For a discussion of the significance of crosses in Ethiopian Orthodox practice, see Jacopo Gnisci and Father Abate Gobena, “Ethiopian Crosses: Art in Motion,” in Africa and Byzantium, ed. Andrea Myers Achi (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2023), 224–26; Daniel SeifeMichael Feleke, “Liturgy and Practice.”

[16] Due to the non-specific nature of bitumen and the frequent admixture of other materials, including plant gums such as gum arabic, difficulties in characterization have long plagued the study of this applied black material, though bitumen or related natural petroleum compounds have often been cited as components. See Esin Atil, W. T. Chase, and Paul Jett, Islamic Metalwork in the Freer Gallery of Art (Freer Gallery of Art, 1985), 40.; Rachel Ward, Islamic Metalwork (British Museum, 1993), 35; Susan La Niece, “Islamic Copper-Based Metalwork from the Eastern Mediterranean: Technical Investigation and Conservation Issues,” Studies in Conservation 55, no. S2 (2013): 35–39. It should be noted that niello, a mixture of metallic sulfides that appears glossy black, may also be applied to metalwork, most typically silver and gold, though rare examples of niello on copper alloy from the ancient and medieval worlds are known. When applied to copper-alloy surfaces, niello typically consists only of copper sulfides, which tend to have a pronounced blue tone. See William Andrew Oddy, Mavis Bimson, and Susan La Niece, “The Composition of Niello Decoration on Gold, Silver, and Bronze of the Antique and Medieval Periods,” Studies in Conservation 28, no. 1 (February 1983): 29–35.

[17] Heather Badamo, “The Shifting Dynamics of Egyptian-Ethiopian Exchange in Christian Art,” in Sciacca, Ethiopia at the Crossroads, 177–83.

[18] Ward, Islamic Metalwork, 111; Doris Behrens-Abouseif, Metalwork from the Arab World and the Mediterranean (Thames & Hudson, 2021), 75. In particular, a number of highly accomplished metalworkers from Mosul (present-day Iraq) are known to have migrated to Cairo, where they or their descendants continued to sign works with the suffix al-mawsili, “from Mosul.” At least twenty-eight individual craftspeople working in Mamluk lands are known to have signed as such (Behrens-Abouseif, Metalwork, 54).

[19] Thérèse Bittar, “Objets en metal importés du monde islamique,” in Lalibela: Capitale de l’art monolithe d’Éthiopie, ed. Jacques Mercier and Claude Lepage (Picard, 2013), 317–23; Deniz Beyazit, “Medieval Islamic Inlaid Metalwork in the Churches of Lalibela,” in Myers Achi, Africa and Byzantium, 235–38.

[20] Bittar, “Objets en metal.” Additional examples are to be found in monasteries around Lalibäla, though these are less well known (Beyazit, “Medieval Islamic Inlaid Metalwork”). It should be noted that not all of these objects are inlaid or overlaid with contrasting metals; beginning around 1400 CE, economic crises and metals shortages in Egypt shifted metalwork production toward debased brass vessels ornamented primarily or solely with engraved lines heightened by applied black material. See J. W. Allan, “Sha’bān, Barqūq, and the Decline of the Mamluk Metalworking Industry,” Muqarnas 2 (1984): 85–94; Bernard O’Kane, The Treasures of Islamic Art in the Museums of Cairo (The American University in Cairo Press, 2006), 169; Behrens-Abouseif, Metalwork, 185.

[21] Kristen Windmuller-Luna, “Making the Global Local: Ethiopian Orthodox Adaptations of Catholic European and Indian Art in the Early Modern Era,” in Sciacca, Ethiopia at the Crossroads, 291–97.

[22] The Ethiopian imperial court not only imported painters and paintings from Latin Europe, but also commissioned works from as far away as France, including a number of early sixteenth-century painted enamels on copper. Verena Krebs, “Ethiopia’s Connections with Late Medieval Europe,” in Sciacca, Ethiopia at the Crossroads, 259–65.

[23] Much of the archeological evidence for Chinese porcelains in medieval Ethiopia indicates they were primarily imported via overseas trade networks dominated by the Muslim sultanates in Ethiopian lands, though sherds of blue-and-white porcelain from the fourteenth–fifteenth century CE have been recovered from Enselalé Church in Šäwa, and there is evidence that a large Chinese vase was employed as a mortuary urn for the neguś (emperor) Särśä Dəngəl (1563–1597 CE) in the church of Mädḫane ʿAläm on Rema Island, Lake Ṭana. See Hannah Parsons-Morgan, “Chinese Ceramic Consumption in Medieval Ethiopia: Archeological Perspective,” Orientations 54, no. 3 (May/June 2023): 34–42, at 41.

[24] Badamo, “Egyptian-Ethiopian Exchange,” 188, fig. 5. Mamluk metalwork was also highly valued, and occasionally revered, in Akan and Asante regions of Ghana, where it similarly inspired local production of nkuduo brass bowls with pseudo-Arabic script. See Raymond Silverman, “Red Gold: Things Made of Copper, Bronze, and Brass,” in Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time, ed. Kathleen Bickford Berzock (Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, in association with Princeton University Press, 2019).

[25] Behrens-Abouseif, Metalwork, 237, 248.

[26] Recent scholarship has posited that the salver was made in lands under Mamluk control on the basis of the signature of Mahmud ibn al-Kurdi, as well as other inscriptions and stylistic elements (Behrens-Abouseif, Metalwork, 237). For further examples of late Mamluk interlace-patterned inlaid metalwork with applied black material, see al-Sabah Collection, inv. no. LNS 590 M a-b and 1421 M.

[27] Behrens-Abouseif, Metalwork, 259.

[28] See al-Sabah Collection, inv. no. LNS 1587 M, for one example.

[29] Regine Schulz, “South Arabia and Its Relations with Ethiopia: A Reciprocal History,” in Sciacca, Ethiopia at the Crossroads, 127–33.

[30] Metropolitan Museum of Art records for acc. no. 1999.103, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/317196.

[31] The possibility that metal inlay in Ethiopian crosses was inspired by Mamluk metalwork has recently been suggested by Gnisci and Abate Gobena, “Ethiopian Crosses.”