In 1993 the Walters Art Museum co-organized the pioneering exhibition African Zion: The Sacred Art of Ethiopia,[1] soon after which the museum began actively acquiring Ethiopian art in various forms: Aksumite coins, intricate metallic and wooden openwork crosses, wall paintings, manuscripts, and painted icons. The twenty Ethiopian icon paintings currently held at the Walters range from the fifteenth to the twentieth century, enabling the study of Ethiopian artists’ materials and techniques across more than five hundred years (Table 1). The Walters’ groundbreaking 2023‒24 exhibition Ethiopia at the Crossroads,[2] a display of about 220 diverse objects from Ethiopia, initiated and inspired multifaceted research on many of the Ethiopian paintings at the museum and provided an unprecedented opportunity for technical research of additional icons loaned to the exhibition from other institutions and private collections. The aim of these studies is to help clarify how Ethiopian painters worked and to add to the currently very limited information available on Ethiopian painting materials and techniques. This note outlines distinguishing elements and production methods and presents some results of recent analysis.

Technical studies of Ethiopian painting began during the mid- to late twentieth century. They were initially focused on the older traditions of Ethiopian church wall paintings and early manuscripts,[3] produced in the earlier part of the Solomonic era from 1270 to the sixteenth century.[4] The earliest extant Ethiopian icon paintings date from the early fifteenth century after Emperor Zärʾa Yaʿǝqob (r. 1434‒1468) promoted the veneration of the Virgin, decreeing that every church have a dedicated altar to Mary.[5] The Virgin became a central subject for paintings, and a need for many painted icons ensued. Compared to other global painting traditions, there has been limited research on Ethiopian painting materials and techniques. In 1994 Marilyn Heldman acknowledged that “documentation of Ethiopian workshop practices is nonexistent.”[6] This continued lack of archival reference documents concerning Ethiopian icon production prompts many questions that are difficult to address without examining and comparing the paintings to try to provide tentative answers. Did artists work alone or in workshops? Did icon painters also illuminate manuscripts, paint murals, and/or engrave figural images on metalwork and wooden crosses? What relationship was there at the Ethiopian court between local artists and foreign artisans brought to work for the same royal patron? Were artists’ materials imported, sourced locally, or both?

After earlier studies focused on wall paintings, Claire Bosc-Tiessé with Sigrid Mirabaud began publishing research on materials in Ethiopian icon paintings around 2016; they stated that due to the dearth of existing documentation, the paintings themselves must be the primary resources.[7] In the wonderfully extensive 2023 catalogue accompanying Ethiopia at the Crossroads, Takele Merid,[8] nearly thirty years after Heldman’s observation, acknowledged that “scholarship on Ethiopian paintings in general and icons in particular is still at an early stage, despite an increase in publications in recent decades.”[9] With still few known references regarding icon production, and few artists’ names and signed works, close examination and technical analysis of these icons is necessary to help answer these questions and expand our knowledge.

Gəʿəz inscriptions on the icons

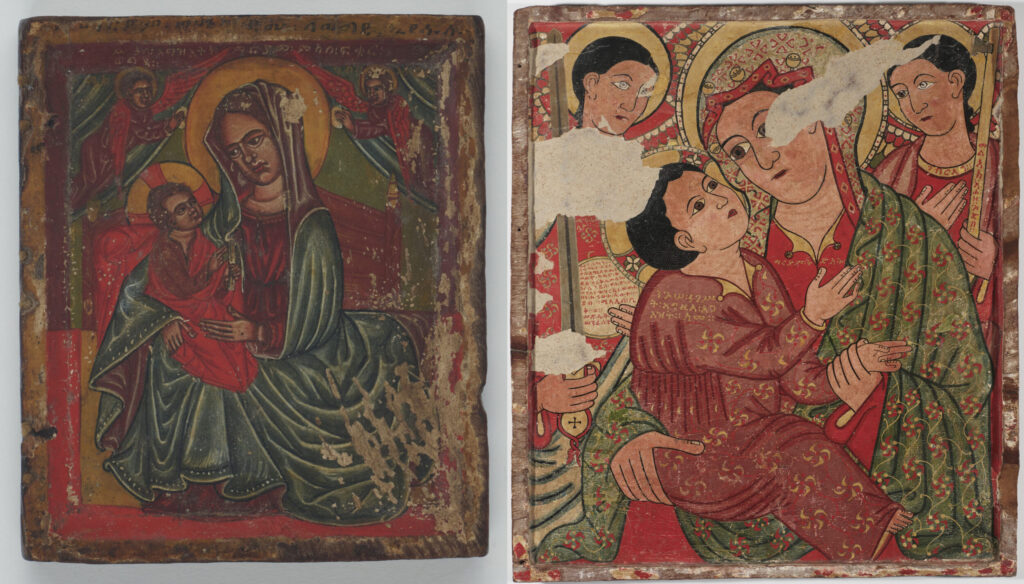

Left: Follower of Niccolò Brancaleon (Italian, active 1480–1521), Right Half of a Diptych Icon with the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Angels, Ethiopia, ca. 1500, glue tempera on panel, 3 7/8 × 3 5/16 in. (9.9 × 8.4 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by an anonymous donor, 2002, acc. no. 36.15

Right: Fǝre Ṣǝyon (Ethiopian, active 1445–1480), Right Panel of a Diptych Icon with the Virgin Mary and Infant Christ and Archangels Michael and Gabriel, Ethiopia, ca. 1445‒1480, glue tempera on panel, 23 × 22 3/4 in. (58.4 × 57.8 cm). Private Collection (IL.1999.4)

It was rare for Ethiopian artists to sign their work. In the few icons that possess signatures, the artist’s name is incorporated into inscriptions in Gəʿəz, the Ethiopian liturgical language,[10] the inclusion of which is a distinguishing feature in both Ethiopian manuscripts and panel paintings. Gəʿəz script is added to backgrounds, frame edges, and, in the example of the Virgin and Child Flanked by Archangels Michael and Gabriel, the right panel of a diptych icon by Fǝre Ṣǝyon on loan to the Walters (IL.1999.4), directly on figural elements (fig. 1). Usually written in red or yellow paint on a contrasting background color, inscriptions in black are also common. Black inscriptions often have a greater sheen than other paints and are more vulnerable to flaking off. The medium used with the black paint is yet to be identified. The Walters’ Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Angels by a follower of Niccolò Brancaleon (acc. no. 36.15) exhibits inscriptions painted in three colors: a bright yellow, a paler white/yellow, and black; two likely dating from its initial creation and a later addition documenting a change of ownership. Gəʿəz inscriptions usually only identify the figures and content of the scenes; however, a few icon inscriptions state who commissioned or painted them. Of these exceptions, Niccolò Brancaleon (a Venetian working at the royal court between 1480 and 1521) signed several of his paintings with his given Ethiopian name, Marquorēwos. Fǝre Ṣǝyon signed a large panel painting at Daga Ǝsṭifanos monastery stating, “This picture was made in the days of our king Zärʾa Yaʿǝqob and our Abbot Yeshaq of Dāgā. The painter [is I] the meek Frē Seyon the sinner . . . ” [11] The panel of Saint George, Jesus Christ, and Saints Peter and Paul (IL.2021.11.1), also examined in this study, was signed by Täklä Maryam around the same time, again describing himself as “the sinner.”[12] From these signatures as sinners, and documentation of Fǝre Ṣǝyon taking monastic vows at Däbrä Gwegwebēn, Heldman surmised both painters were monks and supposed that monasteries were centers of instruction for painting, although “no evidence suggests that this information was committed to painters’ handbooks.”[13]

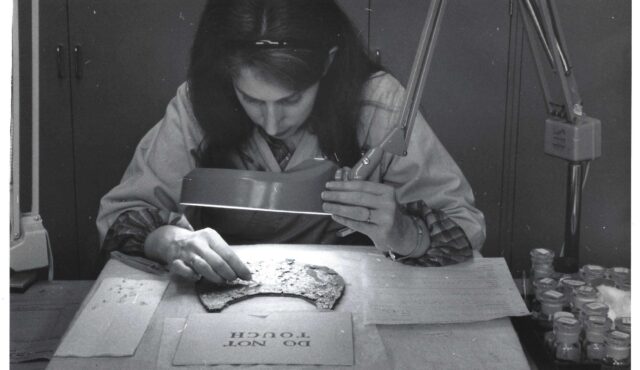

Materials and Comparative Analysis Project

Preparation for Ethiopia at the Crossroads included technical study of several of the Walters icons as well as a trip to Ethiopia with the exhibition curator, Christine Sciacca, where loans and the possible technical examinations of several pieces from the Institute of Ethiopian Studies (IES) were proposed. Ten of the eleven IES icons borrowed for the exhibition were investigated,[14] including the Icon with Equestrian Saints (IESMus4053), which had been part of an earlier technical study in situ at the IES by French researchers; therefore, the Walters’ examination and analysis of this painting was designed to complement those findings.[15]

In total, thirty-four icons were examined: twenty from the Walters, including the Fǝre Ṣǝyon (IL.1999.4) and the Täklä Maryam (IL.2021.11.1) on long-term loan from a private collection, ten from the IES, two from the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM), one from the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA), and one from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) (Table 2). Where time and access permitted, the icons were studied by close looking with the naked eye and a stereomicroscope, documented with a range of photographic and imaging techniques, and analyzed using several non-invasive, non-sampling spot analysis techniques.[16] All the Walters panel paintings and one loan were further studied with microscopic sampling of the wooden supports, and a select few with micro sampling of paint and ground layers. The more detailed results of this technical research concerning preparation and choices of wood supports, grounds, and pigments are published in two conservation essays,[17] including one in the catalogue Ethiopia at the Crossroads, and listed in Tables 1 and 2. In general, the findings from the newly examined paintings correlates with many previous results from these initial studies of the Walters paintings, expanding our knowledge about the longstanding continuity of the Ethiopian icon painting tradition.

Supports

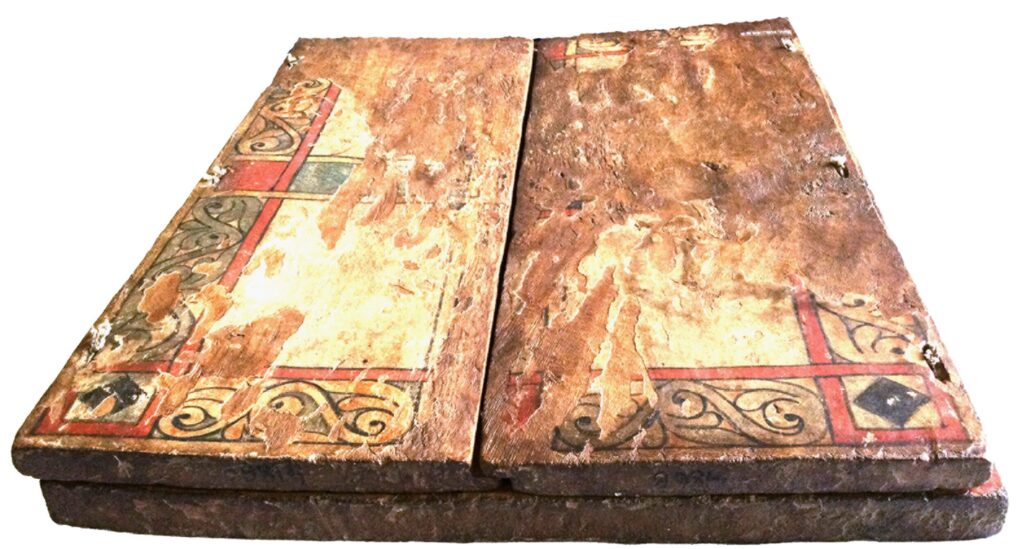

All Ethiopian icons studied to date are rectangular or square in main body shape, although some have arched or shaped tops, such as the two-sided pendant icons (fig. 2). The paintings studied are mostly icons painted on wooden panels, unless they are transferred wall paintings on cloth[18] or are more contemporary paintings on fabric. The wood panel icons have various structural forms, diptychs and triptychs being most common. Although not included in this study, icons with three-dimensional multisided pieces appear from the late sixteenth century, with more complex structures into the twentieth century, such as the Walters’ two-tiered and two-sided Virgin and Child, Saint George and the Young Woman of Beirut, Archangels and Saints (acc. no. 37.2574). The only single-board paintings examined in the group were once part of diptychs or triptychs that are dissociated from their previously attached panels. Often, composite panels have become separated over time; some diptychs (not in this study group) are now composed of panels originally from two different icons. Icon with Equestrian Saints (IESMus4053) is thought to be composed of two outer panels of what originally might have been a triptych.

Top: Unidentified artist, Double-Sided Diptych Icon with Apparition of the Virgin Mary at Dayr al-Maġtas (Däbrä Mǝṭmaq) (front center), Archangels (front left), and Saints (back center and left), Ethiopia (Gondär?), late 17th century, glue tempera on panel, 4 3/8 × 10 1/8 in. (11.11 × 25.7 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 1996, acc. no. 36.8

Bottom: Unidentified artist, Double-Sided Pendant Icon with the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels (front center), Saint George (front left), Kʷərʿatä rəʾəsu (back center), and Saint Täklä Haymanot and Donor (back left), Ethiopia, late 18th century, glue tempera on panel, 3 7/16 × 5 9/16 × 5/8 in. (8.7 × 14.1 × 1.55 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 1996, acc. no. 36.5

No primary sources are known concerning the provision of wood panels for artists. Generally, a tight-grained wood was selected. Earlier studies indicated that two indigenous trees, Cordia africana (wanza) and Olea cf. capensis L. (East African olive), were commonly used for wooden painting supports.[19] Recent anatomical wood analysis of the five fifteenth-century panels at the Walters confirmed the use of wanza for four examples and Canarium cf. schweinfurthii Engl. (African elemi) for the fifth.[20] Wood identification of the later panels in the Walters’ collection indicated a greater variety of woods was used after 1600,[21] coinciding with the period when the royal court moved to Gondär. All identified woods were from trees native to the mountainous landscape of highland Ethiopia, demonstrating use of locally available material. Many of the Walters’ and IES’s panel boards have natural defects such as knots or crotch wood, indicating that unblemished boards of excellent quality were difficult to obtain in the highlands.[22]

Interlocking side wings over the main panel of a closed triptych icon

Fǝre Ṣǝyon (Ethiopian, active 1445–1480), Triptych Icon with the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels and Saints (center), Twelve Apostles and Saints (left), and Prophets and Saints (right), Ethiopia, mid- to late 15th century, tempera on gesso-primed wood, open: 25 3/10 × 39 3/5 × 1 1/4 in. (64.4 × 100.5 × 3.2 cm). Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University, Addis Abäba, IESMus4186

The icon panels were usually prepared with vertical wood grain.[23] All the paintings examined have some visible marks from cutting tools, whether knife or adze,[24] on the uneven front picture planes and the back panel surface, and x-radiographs also reveal toolmark striations. For most panels, especially before the seventeenth century, the center of a solid wood board was carved out to create a recessed picture plane with an integral raised frame border that protected the painted surfaces from damage due to handling and warping. Both boards of diptych panels have raised edges on all four sides. Variations of this format occur with multiboard ensembles. The side wing panels of triptychs may be flat panels that when closed fit flush over the central panel with a raised frame at only the top and bottom, as with the Apparition of the Virgin Mary at Dayr al-Maġtas (Däbrä Mǝțmaq) (IESMus4144). Alternatively, some wings are simply flat panels that close over the main panel, and some have raised frame edges at the top and bottom and down only one of their long edges (more frequently the edge attached to the main panel, providing better edge protection when the triptych is closed). A deviation from this observed norm was noted on the triptych with the Virgin Mary and Christ Child, the Descent into Limbo, and the Crucifixion (PEM, acc. no. E67887), where the long edge frame is on the outer panel edges of the doors when open so that they meet at the center when closed. There are also several variations of flat wood side wings that overlap and interlock where they meet with opposing grooved channels. This protects the edges, and the icon can only be opened by lifting the top overlapped wing first, as with the triptych icons of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels and Saints, Twelve Apostles and Saints, and Prophets and Saints (IESMus4186) (fig. 3) and the Virgin and Child, Twelve Apostles and Saint George, and Fifteen Prophets and Patriarchs (IESMus6617).

Intricate carving and coloration on exterior doors of Double-Sided Diptych Icon with Apparition of the Virgin Mary at Dayr al-Maġtas (Däbrä Mǝṭmaq) (left; see fig. 2, top) and on Diptych Icon with Saint George and Saint Gäbrä Mänfäs Qǝddus and the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels Above Saints (Unidentified artist, Ethiopia, 18th century, tempera on gesso-primed wood, closed: 9 3/4 × 5 1/2 × 1 5/16 in. [24.8 × 13.9 × 3.4 cm]. Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University, Addis Abäba, IESMus3703)

Most of the integral raised frame borders meet the painted surface at a right angle, although some icons like the diptych of Saint George and the Virgin Mary and Infant Christ (acc. no. 36.16) have beveled edges slanting down to the pictorial plane. Generally, the frame edge surfaces are flat and squared; however, later icons exhibit an increased amount of carved decoration. The eighteenth-century diptych icon with Saint George and Saint Gäbrä Mänfäs Qǝddus and the Virgin Mary and Christ Child (IESMus3703) has grooves cut into the front flat of its integral frame surface to emulate more complex European-style frame molding, and all of its outside frame surfaces—like those of the late seventeenth-century double-sided icon with the Apparition of the Virgin Mary at Dayr al-Maġtas (Däbrä Mǝțmaq), Archangels, and Saints (acc. no. 36.8)—are covered with finely detailed decorative carving and paint coloration (fig. 4).

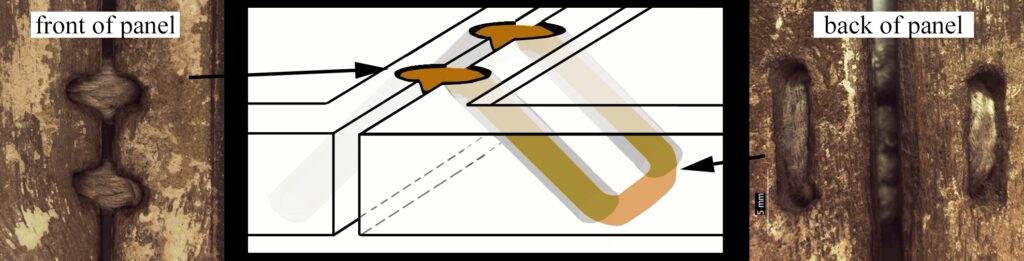

Details of the panel hinge, front and back, with a diagram illustrating the path of the hinging thread looping through angled channels in the Diptych Icon with Saint George and the Virgin Mary and Infant Christ (Unidentified artist, Ethiopia, early 15th century, glue tempera on panel. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase, 2004, acc. no. 36.16). Diagram by Hae Min Park

The composite boards for each icon are normally of similar thickness for diptychs, whereas some triptychs have thinner side wings in relation to the main panel. X-radiographs indicate the boards could have been cut together from the same part of a tree. A unique panel-hinging system was developed to join the boards together while allowing the paintings to open flat (fig. 5).[25] The number of hinges ranges from two to four pairs, independent of the scale of the paintings (the panels studied vary from a few inches to a few feet in height) and whether they were pendants to be worn, panels to be held in the hand, or large and heavy church panels for display. The original hinges, now often missing or replaced, were made of a twisted and plied material such as the sinew, parchment, or vegetable fibers used in the production of Ethiopian manuscripts and satchels.[26] A few icons from the seventeenth century have metal hinges using interlocking screw eyes, as seen on the Apparition of the Virgin Mary at Dayr al-Maġtas (Däbrä Mǝțmaq) (IESMus4144).[27] This piece differs from the other triptychs studied—the central panel is almost twice as thick as the doors that close over it to form a box, and the raised frame edges are attached strips of wood creating an engaged frame rather than an integral frame carved out of the main panel. Most of the current hinges present on icons today are later replacements.

Ground Preparation

Technical studies revealed some variation in preparing layers for panel paintings. Analysis of grounds on icons from the fifteenth century in the Walters’ collection found primarily calcium-sulfate minerals[28] bound in a proteinaceous glue.[29] Both are materials that could be locally sourced. On the fifteenth- to the sixteenth-century icons, a thick layer of ground was generally applied to the surfaces and edges of wood panels,[30] evening out the rough hand-tooled wood texture and buffering the wood to protect against environmental changes that could cause them to warp or crack. Several of the grounds have a minute cratered surface visible to the naked eye, formed as a result of the bursting of tiny air bubbles that must have been present in the mixture when it was applied. The grounds were likely brushed on with some additional manipulation by hand, as supported by the existence of fingerprints in the grounds on both the triptych icon with the Crucifixion, Entombment, Guards at the Tomb, Temptation in the Wilderness, and the Resurrection of Christ (IESMus4126) and the diptych icon with the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels and Apostles and a Saint (acc. no. 36.12). By the seventeenth century, the panel backs were sometimes left as uncoated wood; sometimes given partial grounds, such as on the triptych icon with the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels Above Christ Teaching the Apostles, Scenes from the Life of Christ Above Saints (acc. no. 36.4), or decorative designs, such as on the triptych icon with Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels and Saints (IESMus4186) (fig. 3); or sometimes elaborately carved and selectively painted like Apparition of the Virgin Mary at Dayr al-Maġtas (Däbrä Mǝțmaq), Archangels, and Saints (acc. no. 36.8) (fig. 2, top) and Saint George and Saint Gäbrä Mänfäs Qǝddus and the Virgin Mary and Christ Child (IESMus3703) (see fig. 4).

Canvas interlayer visible in x-radiograph detail of the central panel of Triptych Icon with the Apparition of the Virgin Mary at Dayr al-Maġtas (Däbrä Mǝṭmaq) (Unidentified artist, Ethiopia, ca. 1740‒1755, tempera on gesso-primed cotton on wood, 14 2/5 × 24 3/5 × 1 1/2 in. (36.7 × 62.5 × 3.8 cm). Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University, Addis Abäba, IESMus4144)

In some instances a cloth layer is applied to the wood surface prior to applying the ground layer. In observing a broader array of Ethiopian icons than those in this study, it is notable that only a few fifteenth-century but many more sixteenth‒seventeenth-century Ethiopian panels have cloth interlayers (likely cotton) adhered between the wood and ground.[31] The cloth interlayer texture is very evident in the x-radiograph of the Apparition of the Virgin Mary at Däbrä Mǝțmaq (IESMus4144) (fig. 6).[32] Applying cloth interlayers on wooden panel paintings was common practice in several international schools of icon painting from around the thirteenth through the fifteenth century, but it appears to have only become more common in Ethiopia centuries later as the practice mostly declined elsewhere. It is possible the addition of cloth interlayers may have been influenced by practices brought to Ethiopia by the Jesuits.[33] Unusually, in these later icons, some panels of multiboard paintings received cloth interlayers while others did not. In comparison, all surfaces of the earlier Solomonic panels were treated equally and homogeneously primed with ground.

The preparatory layers for wall paintings were specific to the medium. From the late seventeenth century, many surfaces for wall paintings were prepared by applying a calcium-based wash to mud-mix walls. Pieces of overlapping cloth, probably cotton—as used for the wall paintings Archangel Michael and the Crossing of the Red Sea (acc. no. 36.13.1) and Archangel Raphael and the Miracle of the Sea Monster (acc. no. 36.13.2)—were applied to the mud wall. The fabric may have been presoaked in liquid calcium ground prior to application, or the ground may have been applied to the fabric pieces once they were mounted on the wall, preparing the entire surface for painting. The latter can be seen with close examination of the ground at overlapping areas of fabric on the Nativity, Presentation of Christ in the Temple, and Adoration of the Magi (acc. no. 36.18), especially where an extra small triangular-shaped piece of fabric was inserted to fill a gap between the larger pieces. Practically, it makes sense to apply overlapped fabric sections onto the solid support of a wall, then prime them with a ground, and sketch and paint.[34] To move and glue a large painting composed of overlapping pieces of fabric to a wall would be very unwieldy, and it could come apart at the glued overlaps during attachment.

Drawing

In Ethiopia’s monastic settings, drawing for manuscript illuminations, wall paintings, icon paintings, and incised metal and wooden crosses likely shared a production process over centuries.[35] No drawn incision lines were found on any paintings included in this study, but Heldman noted that on metal crosses “because drawings were incised after the cruciform shape had been cut from the metal sheet, embellishment was not necessarily the responsibility of the metalworker. It seems likely that [at least the drawing for metal cross decoration, if not the incising,] was executed by a painter.”[36] She referenced a brass cross in the IES collection (IESMus4486) and noted, “paintings and incised metal crosses produced for Queen Mentewwàb, regent of Iyasu II (r. 1730‒1755), present such close stylistic and iconographic correspondence that we may assume they are products of the same atelier.” [37]

Interestingly, minute metallic fragments unrelated to the painted images in the icons have been found embedded in the ground and paint of three of the Walters’ fifteenth‒seventeenth-century paintings that were more closely analyzed.[38] This suggests the possibility of artists’ shared workshops or tools.

Details of visible underdrawing and adjustment to final outlines evident after painting

Left: Right panel of Triptych Icon by Fǝre Ṣǝyon (IESMus4186, fig. 3)

Right: Right panel of Diptych Icon with Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels and Apostles and a Saint (Follower of Fǝre Ṣǝyon, Ethiopia, late 15th century, glue tempera on panel. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase, the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 2001, from the Nancy and Robert Nooter Collection, acc. no. 36.12)

Ethiopian painters executed comprehensive fluid drawings directly over the ground layer with a brush or reed pen to delineate compositional elements. These were mostly carbon black lines, sometimes left as is for features such as hair and beards, but mostly applied to demarcate forms with the intent for them to be subsequently painted over with areas of color. Small areas of staggered overlap between these lines exist, where the preliminary drawing can be seen underneath with the naked eye, and small alterations to the final compositions are evident (fig. 7). These two stages of drawing are visible in the majority of the infrared reflectance (IRR) images of the carbon underdrawings of both the Walters’ and IES’s paintings.[39] Sometimes the black was mixed with indigo blue for drawing,[40] as was the practice in some Ethiopian manuscripts.[41] Occasionally, the underpainted lines were used to contribute to overall modeling under thin, lighter-colored flesh paint layers.[42] In the fifteenth century, artists often applied a subsequent additional detailed black outlining, usually in another more concentrated carbon black paint.

Pigments and Paint

For centuries Ethiopian icons were painted with a distemper paint medium that was probably artist-made. The paint was composed of pigments bound in a proteinaceous medium, most likely animal glue,[43] with occasional inclusion of some egg binder. It is not known how the artist’s paints were made and stored, but since panel painters probably also illustrated manuscripts, it is possible that after mixing, paints were put into horns or jars like manuscript inks and paints. Regarding black ink preparation, Anaïs Wion noted, “the pigment is stored dry. Dilution and/or the choice of different binding agents varies according to the requirements of the painter.”[44]

Observations from icons in the Walters collection and those examined from other collections confirm that for centuries a very traditional palette was employed with only slight variation: vermilion red, indigo blue, orpiment yellow, lead white and gypsum, black, and ocher earth pigments, with limited mixing of some of these colors to produce an orange or green.[45] These colors relate to those of the earliest surviving murals and manuscripts, and their use continued through at least the seventeenth century. The distinctive bright-red paint used for centuries could have been made from naturally occurring cinnabar or its chemical twin, synthetically produced vermilion.[46] For a more burgundy red, the mineral hematite was used, likely locally sourced, sometimes mixed with white and vermilion for pinker flesh tones. The more costly vermilion red and orpiment yellow pigments were sometimes extended and amended by red and yellow ocher pigments, which were probably locally sourced. For golden-yellow hues for haloes, robes, and frame edges, Ethiopian artists chose orpiment; gold was rarely used in Ethiopian paintings.[47] The left panel of a diptych icon with Saint George and Abba Gäbrä Märʿawi (IESMus6996B) is a rare example where paint made from ground gold leaf was used on the haloes and horse trappings.[48] Examination under a binocular microscope and cross-section analysis showed that orpiment could be applied selectively, ground coarser or finer for diverse effects, with smooth finely ground paint used for haloes and fabrics, and paint with larger and brighter crystals used on frame edges.[49]

Indigo, which could have been locally sourced or imported, was the only blue pigment identified in the fifteenth-century paintings that were studied. Its use continued for centuries, applied as a thin wash, as a pure opaque color for dark modeling over yellow, in lighter mixtures of indigo and lead white, in mixture with black for dark shading, or as a pure opaque color instead of black. Used since the sixteenth century in Europe, the cobalt glass blue pigment smalt (which could only be ground coarsely so as to not lose its intense color) was identified on Ethiopian icons by Fritz Weihs in 1973.[50] Smalt was very evident on the icon with Saint George and Saint Gäbrä Mänfäs Qǝddus and the Virgin Mary and Christ Child (IESMus3703) in this study, where the large blue crystals were not well bound in their medium and the blue paint consequently suffered areas of loss.

The only greens identified in the early paintings at the Walters were orpiment-indigo mixtures.[51] While other studies have found green earth and copper chloride greens on some fifteenth-century icons,[52] copper greens were more widely adopted after the sixteenth century. Richard Pankhurst noted that by the early nineteenth century “imported materials were, however, not slow to enter the Ethiopian artistic world,” [53] and Henry Salt, in his 1814 written account of his 1810 Ethiopian travels, gives details on commissioning a painting from the court painter at “Chelicut [Č̣äläqot, Cheleqot],” where “the materials employed by this artist were of the most common description, and had been brought by a Greek from Cairo.” [54]

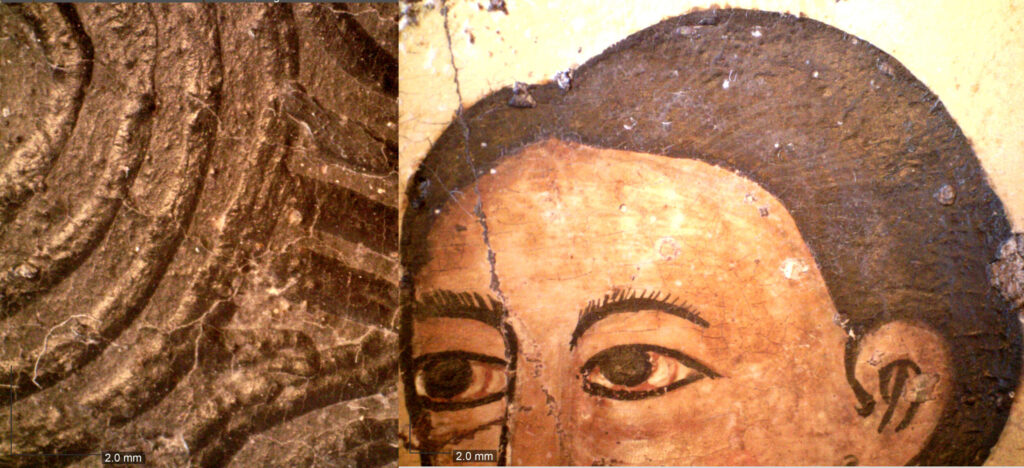

Raking-light details of hair with different types of black paints used to create form and texture

Left: Fǝre Ṣǝyon (Ethiopian, active 1445–1480), Right Panel of a Diptych Icon with the Virgin Mary and Infant Christ and Archangels Michael and Gabriel, Ethiopia, ca. 1445‒1480, glue tempera on panel, 23 × 22 3/4 in. (58.4 × 57.8 cm). Private Collection (IL.1999.4)

Right: Unidentified artist, Right Half of a Diptych Icon with the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels Above Mary with Saints, Ethiopia, late 15th century, glue tempera on panel, 10 7/16 × 7 3/8 in. (26.5 × 18.8 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by an anonymous donor, 2002, acc. no. 36.14

The icons with Virgin and Child (acc. no. 36.15) and Saint George and the Virgin Mary and Infant Christ (acc. no. 36.16) appear to have been painted either by foreign artists working in Ethiopia or by artists educated in and influenced by imported materials and techniques.[55] These icons contain no black paint, the hair is painted brown, and outlines are darker tones of various colors, whereas most of the other icons studied appear to be by local Ethiopian artists and have black paint for hair, beards, and modeling. On the archangels’ swords in the diptych icon with the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels (acc. no. 36.12), indigo rather than black was mixed with lead white to achieve their metal-gray blades, whereas on the Fǝre Ṣǝyon (IL.1999.4) carbon black was mixed with lead white for the same effect. Both these paintings and Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels Above Mary with Saints (acc. no. 36.14) selectively employed more than one black: a dark gray black for overall hair, and a shiny black, with a slightly raised bulk to its surface, to re-emphasize final outlines and accentuate design features such as curls in the figures’ hair (fig. 8).

X-radiograph details showing radiopaque lead white appearing as white eyes on Saint George’s head in Saint George and the Virgin Mary and Infant Christ (Unidentified artist, Ethiopia, early 15th century, glue tempera on panel, 7 3/8 × 11 in. [18.7 × 27.9 cm]. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase, 2004, acc. no. 36.16) (left), and white ground left in reserve for eyes appearing dark on Triptych Icon with the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels Above Christ Teaching the Apostles, Scenes from the Life of Christ, and Saints (Unidentified artist, Ethiopia, early 17th century, glue tempera on panel, 16 3/4 × 22 5/16 in. [42.54 × 56.66 cm]. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 1996, acc. no. 36.4) (right)

For white areas, instead of applying a white-colored paint, the off-white ground layer was sometimes left unpainted to depict the whites of eyes, hair, and horse bodies on select Ethiopian icons,[56] but for a brighter white color, lead white was used, sometimes mixed with orpiment to create highlights. A triptych icon with Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels Above Youthful Christ Teaching, Scenes from the Life of Christ and Equestrian Saints (acc. no. 36.6) and a diptych icon with Saint George and the Virgin Mary and Christ Child (IESMus3893) are very unusual examples of bare ground being left for the entire background. These different techniques for achieving white can be easily compared by studying x-ray images. When the eyes are painted with radiopaque lead white they still appear white, as with the diptych icon Saint George and the Virgin Mary and Infant Christ (acc. no. 36.16); however, where the ground was left in reserve to be the white of the eyes, they are harder to distinguish as they appear dark in the x-radiograph, as with the triptych icon with the Virgin and Child and Scenes from the Life of Christ (acc. no. 36.4) (fig. 9).

Varnish Layers, Coverings, and Cases

Few fifteenth- and sixteenth-century icons were varnished; however, Icon with Equestrian Saints (IESMus4053) displays a discolored possibly oil or resin varnish,[57] and the panels of the two Walters’ icons of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels (acc. nos. 36.12 and 36.14) have vestiges of darkened coatings.[58] Beeswax drips and spots have been identified on panels in both the Walters and IES collections, likely due to candle use during worship.

The IES triptych icon with the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels, Kʷərʿatä rəʾəsu and Saints George and Gäbrä Mänfäs Qǝddus (IESMus3492) has an elaborate leather and bamboo storage and carrying case that has a similar purpose as the thick leather satchels typically made to contain, and sometimes wear, manuscripts.[59] It is likely that many more personal devotional paintings originally had some type of protective cover. Ethiopian icons generally would have been wrapped or covered with a textile.[60] Evidence of textiles wrapped around the edges, or partially covering large paintings, can be seen in many churches in Ethiopia today. No such textiles survive for the icons in this study from the time when they were used in churches or for private devotion.

Iconography, Style Changes, and Attributions

Pictorial techniques and materials are often specific to certain artists, workshops, locations, and periods; therefore, technical information is often used as evidence to support or refute attributions. In the case of fifteenth-century Ethiopia, this method is especially complicated because foreign-produced icons were imported to meet demand, and foreign artists worked in the royal court along with Ethiopian artists, resulting in a blending of iconography and some adoption and interchange of materials and techniques.[61]

For centuries Ethiopian icons have predominantly portrayed the Virgin Mary, the Christ Child, archangels, and a range of saints, especially locally resonant saints. When many figures are present in a scene, they are set in registers separated by painted horizontal lines across the panels, often with lines of descriptive Gəʿəz inscriptions. Different approaches to creating these early paintings are evident in the handling of the paint. The more foreign-influenced icons with the Virgin and Child (acc. no. 36.15) and Saint George and the Virgin Mary and Infant Christ (acc. no. 36.16) have angular figures with white highlights or cross-hatched shading and pure pigment in the darkest areas for shadows in the modeling of drapery and mimicking of three-dimensional form. In contrast, there are no painted shadows used to create form in Ethiopian painting. The technique practiced by Fǝre Ṣǝyon and his followers employs modeling with a bands-of-color system. Forms are generally shaped with three bands of different shades: a light base color followed by a mid-tone band, finished with either pure pigment of the same color for the darkest lines, or a contrasting color.[62] Apart from in the flesh tones of faces, there was little blending of paint to model transition from dark to light of the same color on forms until the early seventeenth century in Gondär.

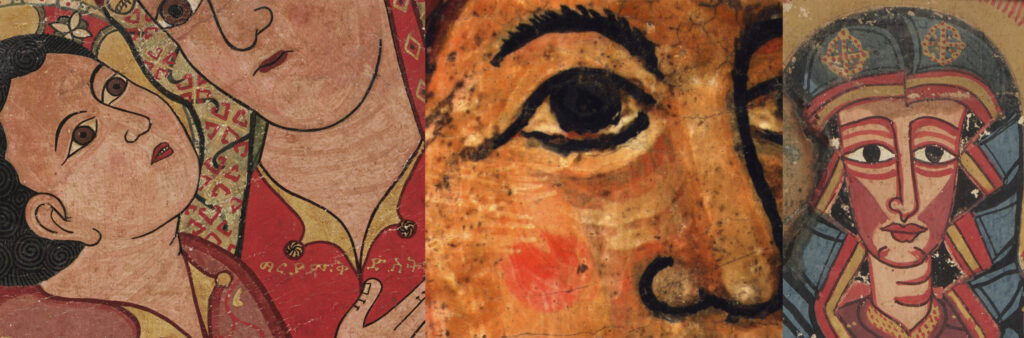

Details of textured flesh in Virgin Mary and Infant Christ by Fǝre Ṣǝyon (IL.1999.4) (left), Right Half of a Diptych Icon with the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels Above Mary with Saints (Unidentified artist, Ethiopia, late 15th century, glue tempera on panel, 10 7/16 × 7 3/8 in. [26.5 × 18.8 cm]. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by an anonymous donor, 2002, acc. no. 36.14) (center), and red paint facial modeling on Diptych with the Virgin and Child Flanked by Archangels with Scenes from the Lives of Christ and the Virgin, and Saints (Unidentified artist, late 17th–early 18th century, tempera on panel, 20 1/2 × 10 3/16 in. [52.07 × 25.87 cm]. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 1996, acc. no. 36.3) (right)

The figures in the Icon with Equestrian Saints (IESMus4053), the Fǝre Ṣǝyon (IL.1999.4), and Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels and Apostles and a Saint (acc. no. 36.12) present less angular traits, with oval-faced, black-haired, rounded figures. Different artists developed distinctive ways of portraying facial characteristics. A feature in some of these icons is the wonderful economy of line, using a continuous thin black line to form noses and eyebrows, and a separate single line to form the heads and chins. Another noted characteristic that several of the Walters and early IES paintings exhibit is slightly raised and subtly different flesh-colored shade lines on necks and facial contours (evident in raking light and in x-radiographs). Perhaps these shade lines are a precursor to the distinctive heavier, red-painted facial modeling that developed in the early Gondärine era (fig. 10). By documenting these observations of differentiating types in Ethiopian icon painting style and technique, alongside manuscript and scroll illuminations, it is hoped more icons can be grouped together to aid in identifying production from specific monastic locations, periods at the royal courts, or specific artists.

Some workshops or artists appear to have worked independently of the court and monasteries, producing unique styles of manuscript illuminations and paintings, such as the late sixteenth- to seventeenth-century triptych icon with Virgin and Child, Scenes from the Life of Christ, and Equestrian Saints (acc. no. 36.6) and the closely related icon of Virgin and Child and Saint George (IESMus3893). These both have an uncommonly simple palette of red-brown, yellow, and a thinly applied pale blue, along with unusual flat white skies created by leaving unpainted grounds, and solid matte black painted foreground areas. Both icons are likely by the same workshop if not the same artist.

Prior to the sixteenth century some monasteries developed distinctive painting styles, possibly based on earlier wall paintings. Unfortunately, much art was lost along with the destruction of key monastic centers during the mid-Solomonic period (1527‒1632) due to several incursions from the southeast of the country by the Oromo people as well as a major military conflict from 1528 to 1543 between the Muslim sultanate of ʿAdal and the Christian Ethiopian empire. Subsequently, artistic production centered around the royal court.[63]

Portuguese forces helped Ethiopia push back the Muslim armies during the ʿAdal war, and Portuguese Jesuit missionaries (from provincial headquarters in Goa, India) followed the soldiers, bringing devotional images of the famous Byzantine icon known as the Madonna of Santa Maria Maggiore to Ethiopia, as well as printed books with engraved illustrations. These new images introduced iconographic changes to Ethiopian paintings. The Crucifixion became a preferred theme, accompanied by scenes from the Passion of Christ, and the Man of Sorrows, referred to in Ethiopia as Kʷərʿatä rəʾəsu.[64] Material changes are also noted, such as the more frequent application of cloth interlayers as part of wood panel preparation (as mentioned earlier). Figures wearing a variety of patterned fabrics emerged, influenced by imported Indian textiles, likely a result of the Jesuits from Goa.[65] The depiction of fabric on figures and pictorial elements became as much about pattern as about creating form, almost to the point of abstraction on some panels and manuscripts. The Virgin’s dress on the Virgin and Child, Twelve Apostles and Saint George, and Fifteen Prophets and Patriarchs (IESMus6617) exemplifies this development where it fills the main panel with its large floral-like pattern. Interestingly, the dress of the Virgin at the center of the eighteenth-century Apparition of the Virgin Mary at Däbrä Mǝțmaq (IESMus4144) is not only textured with raised floral patterns but is symbolically designed to be the shape of the country of Ethiopia, and the bands of background color behind her create the Ethiopian flag.

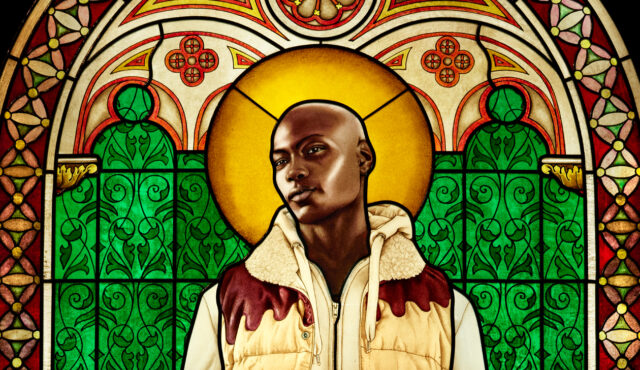

In 1625, as a result of contact with the Jesuits, Emperor Susǝnyos publicly converted to the Roman Catholic faith, separating from the traditional Orthodox Ethiopian Church. He later abdicated in favor of his son Fasilädäs, who established the royal court at Gondär in the 1630s and restored the Orthodox Ethiopian Church. A productive time for Ethiopian arts, the Gondärine period is generally separated into two main stylistic phases. The First Gondärine period[66] is characterized by bold, rich colors and little modeling of forms except for thin parallel lines; clothing displays decorative patterns, and the palette is predominantly red, yellow, blue, and bright green. Facial features and outlines are executed in contour-like layers of dark red, making them masklike, as evident on Saint George and Saint Gäbrä Mänfäs Qǝddus and the Virgin Mary and Christ Child (IESMus3703) and Virgin and Child Flanked by Archangels with Scenes from the Lives of Christ and the Virgin, and Saints (acc. no. 36.3). Paintings from the Second Gondärine era[67] are generally darker toned but still have a strong color palette. The lines delineating forms are lighter, and blended shading creates volume and form, resulting in more naturalistic representation for figures and faces.

Painting subjects inspired by Western prints began to appear during the eighteenth century. Alongside architecture and icons, metalwork crosses with incised depictions of the Virgin, Christ, and the saints were produced during this period. Heldman noted, “by the seventeenth century production of religious art had ceased to be the primary domain of the monk, and, although the priest-artisans or deacon-artisans who produced religious art were not removed from lay society like monk-artisans, they, as creators of religious art, were not grouped with low-status craft workers.”[68] New patterns of patronage began in the Gondärine period (1636‒1855) resulting in changes to the content of icons.[69] Toward the eighteenth century, more noblemen and high-ranking ecclesiastics, rather than emperors and kings, commissioned paintings, and many of these paintings now depicted donors and patrons, who often donated them to churches or monasteries. During this productive period a broader range of colors were used for painting, yet, in general, each was still applied separately rather than blending or mixing them.

By the nineteenth century, concurrent with religious painting, secular scenes depicting battles and more recent historical events became more common. Many of these paintings reveal a more varied palette. Annegret Marx writes, “pigments in some Ethiopian paintings and manuscripts show that European synthetic pigments were available in Ethiopia during the nineteenth century and, consequently, a well-developed market between Europe and Ethiopia must have existed already during this period.” [70] Both Prussian blue and synthetic ultramarine blue have been identified in nineteenth-century church paintings.[71] After the Second World War, the use of a greater range of imported synthetic colors became common. Purchased acrylic paint began replacing domestically prepared glue tempera paints as a medium. Discussing the use of modern synthetic dye-stuffs on more contemporary Ethiopian paintings, St. Fitz remarked, “One can assume that all these colors were not used before 1900 . . .”[72] Increasingly by the 1960s, alongside icon paintings still produced for churches, icons and manuscripts were also created for the tourist market, such as the narrative scene paintings in the Walters collection of Queen of Sheba and King Solomon Conceiving King Mǝnǝlik I (acc. no. 1994.7.20) and Daily-Life Activities (acc. no. 1994.7.19).

Conclusion

This note provides foundational research with an aim to lead to future studies. Findings thus far demonstrate a consistency in icon production related to wood panel preparation and ground preparation and format, and in materiality with an adherence to a select and consistent pigment palette with few variations over centuries. Close study of the icons reveals the development of a distinctly Ethiopian painting process and style that influenced and was influenced by their spheres of contact yet remained clearly their own.

Technical research of these Ethiopian icons is essential to understand, appreciate, and properly care for them as objects. Beyond understanding the origins of the icons and the contexts of their creation, knowledge of the materials employed in their production is important to recognize possible mechanisms of aging and decay, and to best preserve the icons. For example, the orpiment yellow Gəʿəz inscriptions that cover the background of the icon by Täklä Maryam (IL.2021.1.1) have changed drastically in the thirty years from when it was photographically documented for the African Zion exhibition. The inscriptions are now almost illegible against the red background, presumably due to deterioration of the arsenic yellow pigment. The Walters plans to undertake future research on the lettering, with possible sampling, to clarify the cause of deterioration. In addition, the inscriptions could be captured with new imaging equipment and methods for a full translation before possible further changes.

There is still more knowledge to be gained from the technical studies and examinations done for this project in a limited timeframe; however, the work presented provides groundwork information that can be applied to subsequent research. Future study of the imaging that was captured should enable more direct comparisons between paintings and manuscripts to further differentiate artists’ hands and workshops. It is hoped the observations made here, combined with contributions from earlier research, help to build a corpus of knowledge on the material and technical development of historic Ethiopian painting and to answer questions about artists, workshops, and their choice of materials.

Examining Ethiopian icon production in a greater world context reveals how it changed iconographically over time, but in their materiality these icons “represent the organic and conservative continuation of the ancient tradition” through the nineteenth century.[73] Research on Ethiopian painting needs more technical studies of paintings with scientific analysis of materials used, hopefully combined with complementary art historical research and detailed investigation of historical sources.

A central goal of this research is to disseminate findings to the IES, scholars, museums, and the general public, providing access for further comparative studies. Collaboration that involves focused multidisciplinary study to combine knowledge should lead to a more complete understanding of these icons. It is hoped more institutions can undertake this type of research so that in the future a database of historical, technical, and analytical information about Ethiopian painting might be established.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Walters Art Museum staff who aided in this research and journal, especially my current colleagues Dr. Christine Sciacca and Dr. Annette Ortiz Miranda, and previous colleagues Dr. Glenn Gates and Hae Min Park, for their assistance and guidance. Thanks must also be given to Dr. Takele Merid, Director of the Institute for Ethiopian studies, and to the Peabody Essex Museum, the Toledo Museum of Art, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts for the opportunity to examine their artworks while on loan to the Ethiopia at the Crossroads exhibition.

[1] The arts group InterCultura co-organized the eight-venue traveling show with the Walters Art Gallery (now Museum) in 1993‒96.

[2] Ethiopia at the Crossroads, exhibition co-organized by and presented at The Walters Art Museum from December 3, 2023, to March 3, 2024; the Peabody Essex Museum from April 13 to July 7, 2024; and the Toledo Museum of Art from August 17 to November 10, 2024.

[3] Ethiopian manuscripts in particular have undergone a considerable amount of documentation and cataloguing with projects such as the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library (EMML) project, the Mäzgäbä Sǝǝlat project, and the Ethio-SPaRe project. There is no equivalent for Ethiopian paintings.

[4] The Solomonic dynasty refers to the period when Ethiopia was ruled by claimed descendants of Mǝnǝlik I, son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, from 1270 to 1974.

[5] Marilyn E. Heldman, The Marian Icons of the Painter Frē Ṣeyon: A Study in Fifteenth-Century Ethiopian Art, Patronage, and Spirituality (Harrassowitz, 1994), 166.

[6] Heldman, The Marian Icons, 80.

[7] “Les objets sont donc non seulement leurs propres mais aussi leurs premières sources. L’étude approfondie, non seulement de leur iconographie ou de leurs styles mais aussi de leur technologie, s’avère cruciale pour la confronter aux quelques données générales fournies par les textes et à celles issues de l’analyse des matériaux.” Claire Bosc-Tiessé and Sigrid Mirabaud, “Une archéologie des icônes éthiopiennes: Matériaux, techniques et auctorialité au XVe siècle.” Images re-vues 13 (2016): 1‒48, https://doi.org/10.4000/imagesrevues.3927.

[8] Takele Merid is Assistant Professor of Social Anthropology and Director of the Institute of Ethiopian Studies (IES), Addis Ababa University.

[9] Takele Merid, “Some Observations on Ethiopian Orthodox Täwaḥədo Icon Paintings (Gäbäta Səʾəloč),” in Ethiopia at the Crossroads, ed. Christine Sciacca (Walters Art Museum in Association with Yale University Press, 2023), 69.

[10] Gəʿəz was the primary historic language of the Aksumite Kingdom and is still the liturgical language of the Ethiopian church. According to some scholars it may be best practice to refer to the language as Gəʿəz and the script as Ethiopic. See Sean Michael Winslow, “Ethiopian Manuscript Culture: Practices and Contexts” (PhD diss., University of Toronto, 2015), chap. 2, http://hdl.handle.net/1807/71392.

[11] Heldman, The Marian Icons, 25.

[12] Heldman, The Marian Icons, 25.

[13] Marilyn E. Heldman, “Creating Religious Art: The Status of Artisans in Highland Christian Ethiopia,” Aethiopica 1 (1998), 133n11.

[14] The eleventh icon is a fifteenth- to seventeenth-century icon of the Virgin and Child that is a foreign Italo-Cretan import and was therefore not included in this study of Ethiopian icons.

[15] Sigrid Mirabaud, Méliné Miguirditchian, and Claire Bosc-Tiessé, “Étude d’un corpus d’icônes datées des XVe et XVIe siècles conservées au musée de l’Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Université d’Addis Abeba, Éthiopie.” ICOM Committee for Conservation 2011 Lisbon Preprints: 16th Triennial Conference, Lisbon 19‒23 September 2011, ed. J. Bridgland, 1‒11 (ICOM, 2011).

[16] Infrared reflectance (IRR) imaging undertaken between 1100 and 2400 nm using a 1280JS camera with 50 mm Edmonds optical lens and an incandescent 250 W light source to reveal carbon-based underpainting; x-radiography at appropriate parameters (kV, μA, and sec) for each panel using CR digital film and GE digital plate scanner; x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) using an Artax 800 with a rhodium anode at 50kV and 700 microamps, helium purge for certain samples, no filter, 1.5 mm collimator for 120 seconds; fiber optics reflectance spectroscopy (FORS) undertaken between 400 and 2400 nm using FieldSpec 4HR and IndicoPro software.

[17] Karen French, Glenn Gates, Hae Min Park, and Christine Sciacca, “Transmitting Ideas: A Symbiotic Relationship; Local and Foreign Artistic Exchanges at the Fifteenth-Century Ethiopian Court,” in Migrants: Art, Artists, Materials and Ideas Crossing Borders, edited by Lucy Wrapson, Victoria Sutcliffe, Sally Woodcock, and Spike Bucklow (Archetype Publications in association with the Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge, 2019), 201; Karen French, Hae Min Park, Abigail Quandt, and Glenn Gates, “Technical Research on a Selection of Ethiopian Manuscripts and Panel Paintings in the Walters Art Museum,” in Sciacca, Ethiopia at the Crossroads, 267‒79.

[18] Three of the Walters icons, Archangel Michael and the Crossing of the Red Sea (acc. no. 36.13.1), Archangel Raphael and the Miracle of the Sea Monster (acc. no. 36.13.2), and Nativity, Presentation of Christ in the Temple, and Adoration of the Magi (acc. no. 36.18), were originally painted on overlapping fabric pieces, grounded and mounted to a church interior, likely a type of mud and plant fiber wall. They were subsequently extracted (usually by peeling and cutting) from the walls and mounted with adhesive to new fabric supports.

[19] Stanislaw Chojnacki, “Icons,” in Elizabeth Cross Langmuir, Stanisław Chojnacki, and Peter Fetchko, Ethiopia: The Christian Art of an African Nation; The Langmuir Collection, Peabody Museum of Salem (Peabody Museum of Salem, 1978), 7; Bosc-Tiessé and Mirabaud, “Une archéologie des icônes éthiopiennes.”

[20] Three microscopic samples of wood were taken from the transverse, radial, and tangential faces of all boards of each painting by Karen French and identified by Victoria Asensi of Xylodata SARL in Paris, using optical microscopy of thin sections.

[21] French et al., “Technical Research,” 270.

[22] Right Half of a Diptych Icon of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Angels (acc. no. 36.15) attributed to a follower of Niccolò Brancaleon appears to be on wood from a branch crotch. Poor choices of wood for panels could indicate the scarcity of good old growth trees in the Ethiopian highlands.

[23] The Fǝre Ṣǝyon on loan to the Walters from a private collection (IL.1999.4) is unusual in being the only horizontal wood grained panel in the entire group studied. It is also almost four times as large and thicker than the other Walters paintings.

[24] An ancient and adaptable cutting tool, similar to an axe, but with a cutting-edge perpendicular to the handle rather than parallel.

[25] French et al., “Technical Research,” 270‒72. Note this panel hinging also relates closely to the method of board attachment for Ethiopian manuscripts.

[26] French et al., 279.

[27] Two of the applied metal screw eye hinges pulled out and broke wood away from the frame, requiring repairs with reinforced thread hinges.

[28] Identified by Raman spectroscopy (RS). French et al., “Technical Research,” 272.

[29] An adhesive made from gelatin (a protein derived from collagen) identified with Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). French et al., 272.

[30] An exception was the panel by the follower of Brancaleon, distinctive among the pre-1600 paintings for having no evident verso ground. It may have worn away or been removed, but the unusually smooth wood finish suggests a ground was never applied. The pre-application of a sizing layer to seal the wood prior to grounding was indistinguishable in the paintings studied. Delamination at the wood-ground interfaces on many Ethiopian wooden icons further indicates this was not part of Ethiopian panel painting preparation.

[31] Cotton is suggested based on observable characteristics and easy availability of cotton fabric.

[32] Each panel of IESMus4144 has a complete piece of fabric over the entire front surface.

[33] The Jesuit (or Society of Jesus) mission was carried out in the Ethiopian highlands from 1557 to 1632.

[34] On the back of the Walters’ Archangel Raphael and the Miracle of the Sea Monster (acc. no. 36.13.2), a small rough outline of a sketched head is visible under adhesive remnants on the lowest section of the three-piece fabric support. The sketch does not relate to the composition on the front but may indicate some sketching could be done directly on the fabric pieces before mounting, intended to be visible through the ground for painting.

[35] Heldman attributed an incised ebony wood cross (IESMus4329) to Fǝre Ṣǝyon. The Marian Icons, 50.

[36] Heldman, The Marian Icons, 64.

[37] Marilyn Heldman with Stuart C. Munro-Hay, African Zion: The Sacred Art of Ethiopia (Yale University Press in association with Inter-Cultura, Fort Worth; the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, and the Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa, 1993), Processional Cross, cat. no. 114.

[38] To date, shiny metallic fragments have been observed embedded in the paint and ground of three Walters icons (acc. nos. 36.3, 36.15, 36.16); however, several icons remain to be examined for this.

[39] IRR can be used to reveal detailed design lines in carbon black since the carbon absorbs infrared radiation efficiently in reflectography.

[40] Indigo blue was confirmed using false-color infrared imaging (FCIR), FORS, and Raman spectroscopy (RS).

[41] French et al., “Technical Research,” 268.

[42] Virgin Mary and Christ Child Flanked by Archangels Above Mary with Saints (acc. no. 36.14) demonstrates this well where the Christ Child’s chest structure is drawn with carbon lines that give it form through the flesh-colored paint.

[43]Animal skin parts left over from parchment-making may have been used for the animal glue. The infrared absorption bands Amide I and II vibrations, characteristic of proteinaceous binding media such as glue and egg yolk, were observed in all FTIR data. See Frank S. Parker, “Amides and Amines,” in Applications of Infrared Spectroscopy in Biochemistry, Biology, and Medicine (Springer, 1971), 165‒66; and Bosc-Tiessé and Mirabaud, “Une archéologie des icônes éthiopiennes,” 18.

[44] Anaïs Wion, “An Analysis of 17th-Century Ethiopian Pigments,” in The Indigenous and the Foreign in Christian Ethiopian Art: On Portuguese-Ethiopian contacts in the 16th–17th Centuries, ed. Manuel João Ramos and Isabel Boavida (Ashgate, 2004), 107.

[45] Stanislaw Chojnacki, in collaboration with Carolyn Gossage, Ethiopian Icons: Catalogue of the Collection of the Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University (Skira, 2000), 19‒48; Claire Bosc-Tiessé, Méliné Miguirditchian, Sigrid Mirabaud, and Raphaël Roig, Śeʿel: Spirit and Materials of Ethiopian Icons (Centre français des études éthiopiennes, 2010); Mirabaud et al., “Étude d’un corpus”; Kidane Fanta Gebremariam, Lise Kvittingen, and Floriel-Gabriel Banica, “Application of a Portable XRF Analyzer to Investigate the Medieval Wall Paintings of Yemrehanna Krestos Church, Ethiopia.” X-ray Spectrometry 42, no. 6 (2013): 462–69; Bosc-Tiessé and Mirabaud, “Une archéologie des icônes éthiopiennes”; Kidane Fanta Gebremariam,“Physicochemical Investigation of an Icon Painting from the Enda Abba Garima Monastery, Ethiopia.” Poster presented at the ICOM Committee for Conservation 18th Triennial Conference, Copenhagen, 4–7 September 2017, https://www.icom-cc-publications-online.org/1639/Physicochemical-investigation-of-an-icon-painting-from-the-Enda-Abba-Garima-Monastery-Ethiopia.

[46] X-radiography clearly identified vermilion, this was confirmed with XRF, Raman, and FORS.

[47] Gold was available in Ethiopia and was an Ethiopian export, but evidence suggests from the late eighth to the twelfth century CE some of the Ethiopian kingdom’s natural resources, such as gold and ivory, were depleted.

[48] The artist for this icon was likely a European working in Ethiopia, rather than Ethiopian.

[49] French et al., “A Symbiotic Relationship,” 201.

[50] Smalt was first found on an Ethiopian icon in the IES’s collection, IESMus4793. Fritz Weihs, “Some Technical Details Concerning Ethiopian Icons,” in Religiöse Kunst Äthiopiens / / Religious Art of Ethiopia, ed. Walter Raunig, 298–305 (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen, 1973), 303.

[51] This bright green mixture, sometimes known as vergaut, is documented on Roman-period Egyptian mummy portraits and in manuscripts since at least the eighth century CE. It continued to be used in Ethiopian manuscripts through the eighteenth century.

[52] Mirabaud et al., “Étude d’un corpus.”

[53] Richard Pankhurst, “Some Notes for a History of Ethiopian Secular Art, ” Ethiopia Observer 10, no. 1 (1966): 12.

[54] Henry Salt, A Voyage to Abyssinia (1814), 394‒95, https://archive.org/details/voyageAbyssinia00Salt/page/394/mode/2up.

[55] These icons evince knowledge of Italianate type icon painting. See the section on iconography, style changes, and attributions for further explanation.

[56] This has also been noted with some Walters manuscripts where bare parchment was used for white color.

[57] This icon (formed of two panels that may possibly have formed a triptych but currently displays as a diptych) was examined by the author with a binocular microscope. It is also discussed in Bosc-Tiessé and Mirabaud, “Une archéologie des icônes éthiopiennes,” 22‒34.

[58] Examination of the dark areas on the frame and corner edges of the panels of acc. no. 36.12 have, to date, only shown materials related to residues from handling. The brown remnants on acc. no. 36.14 are yet to be analyzed.

[59] Bill Hanscom, “Towards a Morphology of the Ethiopian Book Satchel,” in Suave Mechanicals: Essays in the History of Bookbinding (Legacy Press, 2016), 3:300‒305.

[60] While undertaking research for the Ethiopia at the Crossroads exhibition with members of the Community Advisory Group from the DC, Maryland, and Virginia area (DMV), several individuals spoke about icon paintings being wrapped or curtained with a textile.

[61] French et al., “A Symbiotic Relationship.”

[62] French et al., “Technical Research,” 276‒77.

[63] Marilyn E. Heldman, “An Ewostathian Style and the Gunda Gunde Style in Fifteenth-Century Ethiopian Manuscript Illumination,” in Proceedings of the First International Conference on the History of Ethiopian Art, ed. Richard Pankhurst (Pindar Press, 1989), 5‒14, 133‒39.

[64] Likely modeled on a Flemish Ecce Homo, which was gifted to the Ethiopian royal court in the early sixteenth century.

[65] Kristen Windmuller-Luna, “Making the Global Local: Ethiopian Orthodox Adaptations of Catholic European and Indian Art in the Early Modern Era,” in Sciacca, Ethiopia at the Crossroads, 293‒95.

[66] The First Gondärine period was from the mid-seventeenth century to the early eighteenth.

[67] The Second Gondärine period began in the late seventeenth century and lasted through the nineteenth.

[68] Heldman, “Creating Religious Art,” 143.

[69] Heldman and Munro-Hay, African Zion, 195.

[70] Annegret Marx, “Indigo, Smalt, Ultramarine – A Change of Blue Paints in Traditional Ethiopian Church Paintings in the 19th Century Sets a Benchmark for Dating,” in Ethiopian Studies at the End of the Second Millenium: Proceedings of the XIVth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, November 6‒11, 2000, Addis Ababa (Addis Ababa University, Institute of Ethiopian Studies, 2002), 1:215‒32.

[71] Heidi Cutts, Lynne Harrison, Catherine Higgitt, Pippa Cruickshank, “The Image Revealed: Study and Conservation of a Mid-Nineteenth-Century Ethiopian Church Painting,” British Museum Technical Research Bulletin 4 (2010): 10.

[72] Author’s translation of “Man kann davon ausgehen, dass alle diese Farben nicht vor 1900 verwendet wurden.” St. Fitz, “Untersuchung der Farben von neuerer äthiopischer Volksmalerei,” in Mensch und Geschichte in Äthiopiens Volksmalerei, ed. Girma Fisseha and Walter Raunig (Umschau-Verlag, 1985), 28‒29.

[73] Denis Nosnitsin, “Ethiopian Manuscripts and Ethiopian Manuscript Studies: A Brief Overview and Evaluation,” Gazette du livre médiéval 58, no. 1 (2012): 3.