In preparation for Ethiopia at the Crossroads, a major exhibition of ancient to contemporary Ethiopian art that was on view at the Walters Art Museum and two other venues from 2023 to 2024,[1] technical research was undertaken on sixty-seven Ethiopian manuscripts in the collection that date from the early fourteenth to the early twentieth century.[2] The methods of production of each type of manuscript were documented, and, in ten cases, the inks and pigments used for writing and illumination were analyzed. (See table “Pigment Analysis of Ethiopian Manuscripts” for a detailed breakdown of results.) The authors were also able to examine and analyze the pigments of four manuscripts on loan to the exhibition. This note provides an overview of the characteristic features and production methods of each type of manuscript and presents the results of the analysis. Trends inspired by local traditions and international influences will be explored, and the extent to which political exchanges and international trade impacted the use of pigments and dyes in Ethiopia from the early fourteenth through the nineteenth century will be discussed.

Types of Manuscripts

The written culture of Ethiopia is unusual for the variety of manuscripts that were produced throughout its long history. The most common type of manuscript was the codex (mäṣḥaf). Codices varied in content and overall size depending on their intended use. Large- to medium-sized Gospels, Psalters, and Homilaries, as well as uniquely Ethiopian texts such as the Täʾammərä Maryam, or Miracles of the Virgin Mary, were made for the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwaḥədo Church and typically illuminated. Smaller codices containing devotional prayers or hymns were usually made for members of the clergy and were minimally decorated. Given the extensive losses to Ethiopian cultural heritage that occurred with the rise of Islam between the seventh century and the twelfth century, only a few pre-thirteenth-century Ethiopian codices are known. The earliest and most unusual of these is the richly illuminated Abba Gärima Gospels,[3] which has been dated by some to between the late fifth and the early seventh centuries.[4] There are a few surviving thirteenth-century codices and many more examples from the fourteenth century onwards. For this study, three bound codices (Gospel Book, early 14th century, Walters Art Museum, acc. no. W.836; Gospel Book, early 16th century, Walters Art Museum, acc. no. W.850; and Gondär Homiliary, late 17th century, Walters Art Museum, acc. no. W.835) and one single leaf (Double-Sided Leaf with Christ’s Entombment and Resurrection, late 14th century, Walters Art Museum, acc. no. W.839) were analyzed, in addition to two codices from other collections (Zir Ganela Gospels, 1400‒1401, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.828, and Homilies of Saint Michael, 1770s, The Melikian Collection, Melikian 389).[5]

The accordion-fold chained manuscript (sənsul) is particular to Ethiopia and was popular from the fifteenth through the eighteenth century.[6] Sənsuls were made from one or more strips of parchment that were sewn together, folded accordion style and painted on one or both sides.[7] The number of panels might vary from eight to forty-eight. Inscriptions written in Gǝʿǝz in red ink identified the individual saints or scenes depicted on each panel. Some sənsuls might also have supplications and short prayers that include the name of the donor or owner.[8] Although there are a few larger examples, the majority of surviving sənsuls are small enough to fit comfortably in one’s hands.[9] The earlier sənsuls bear images of saints and holy figures with the Virgin and Child in the center, while those produced during the First Gondärine period (mid-seventeenth through early eighteenth century) usually depict episodes from the life of the Virgin or narrative scenes from the Bible or a saint’s life. Analysis was undertaken on a double-sided leaf from a fragmentary sənsul (16th century, Walters Art Museum, acc. no. W.927)[10] and a one-sided Gondärine sənsul (late 17th century, Walters Art Museum, acc. no. 36.10). Also analyzed were two early sənsuls on loan to the Walters (15th century, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, acc. no. 2012.301; 15th‒early 16th century, Peabody Essex Museum, acc. no. E67892).

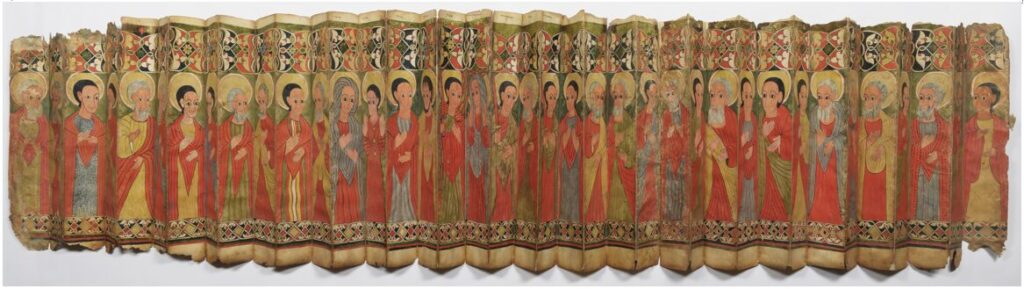

Liturgical fans (märäwǝḥ) were made of several large, rectangular sheets of parchment that were sewn together and folded into an accordion. Images of saints and apostles from the Old and New Testaments were painted on the whiter flesh side of the narrow panels, while decorative bands (ḥaräg) spanned the width of the composite object.[11] These fans are classified as manuscripts due to the inscriptions that were usually written in Gǝʿǝz in the blank upper margin. When in use, the fans would be opened out into a large circle, approximately 120‒130 cm in diameter, with the image of the Virgin at the apex. Only seven of these fans, which date between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, survive today.[12] These include six in Ethiopia and one in the Walters collection (Folding Processional Icon in the Shape of a Fan, late 15th century, Walters Art Museum, acc. no. 36.9), which was part of the present study.

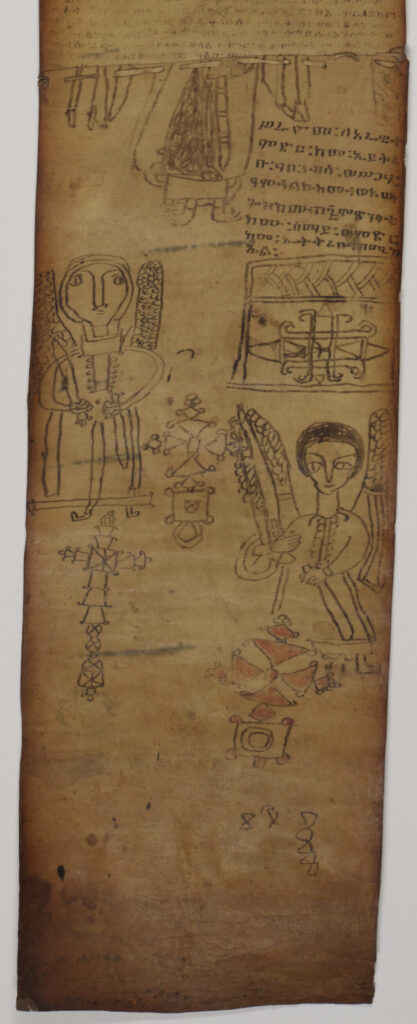

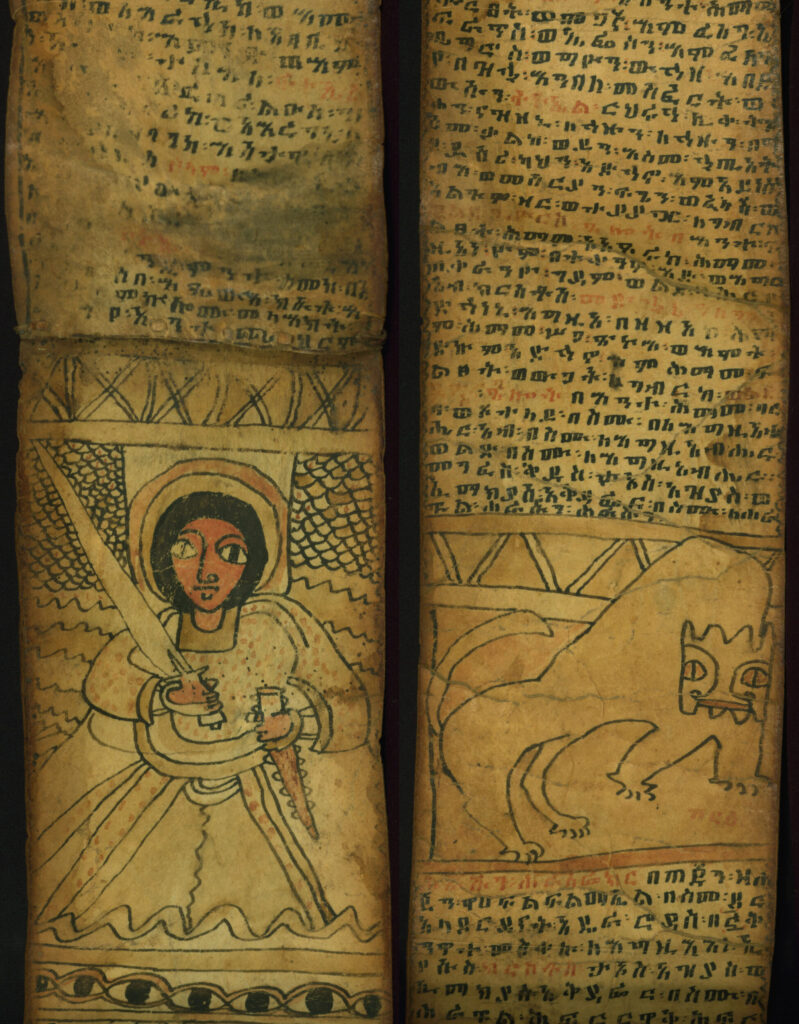

Healing or magic scrolls (kǝtab) were made of long, vertically oriented strips of parchment that were sewn together, written with special prayers and painted on one side with figurative images and magical talismans.[13] Depending on their intended use, healing scrolls could vary in size from 4 to 25 cm in width and from 40 to 200 cm in length.[14] An individual would commission a scroll from a däbtära, usually an unordained cleric of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, to protect them from the evil eye, heal them from physical or spiritual illnesses, assist women in conception, and protect them during childbirth.[15] The prayers and images were chosen based upon the client’s name, date of birth, astrological sign, and symptoms.[16] The earliest known example dates to the sixteenth century,[17] while the majority of scrolls in collections today were produced during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Three of these later scrolls (19th or 20th century, Walters Art Museum, acc. nos. W.845, W.947, and W.954) were selected for analysis.

Preparation for Writing and Illumination

In the case of Ethiopian codices, before the gatherings were formed, the bifolios were pricked and blind ruled with a blunt point to guide the writing. In fourteenth- to sixteenth-century Gospel books it is common to find inscribed lines that were also made for the folios to be illuminated. In the earliest examples, scribes used the vertical lines made for the two columns of text to center depictions of the Evangelists on the folios. Horizontal and vertical lines were frequently added for the geometric designs placed in the upper half of the folio. This practice is seen in a Gospels codex (Walters, acc. no. W.836) and in two unrelated Gospel book leaves (late 14th century, Walters, acc. nos. W.839 and W.840).[18] Pin holes in the foreheads of the Evangelists in the two single leaves from the Walters (acc. nos. W.839 and W.840), in a contemporary Gospel leaf (late 14th‒early 15th century, J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 89 [2005.3]) and in a slightly later Gospel book (ca. 1480–1520, J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 105 [2010.17]) indicate that a compass was used to create the haloes.[19] Scribes/artists of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, who produced richly illustrated codices of the Miracles of Mary, did not prick and rule their designs prior to painting. This allowed the artists to paint several scenes on a single folio and, in general, to work more freely.

Three leaves survive from a double-sided sənsul that was likely produced at the monastery of Gundä Gunde (16th century, Walters Art Museum, acc. nos. W.927, W.928, and W.929).[20] When compared to contemporary examples, this sənsul is unusual in the extent to which the leaves were pricked and ruled prior to painting. Horizontal lines served as guides for the design and outer borders, while vertical lines aided the scribe in positioning the figures within the frames.[21] A near contemporary sənsul (15th‒early 16th century, Peabody Essex Museum, acc. no. E67892) has only a few pricking holes and ruling lines to aid in the placement of the saints on each panel. Similar to the practice observed in Ethiopian codices starting in the First Gondärine period of the late seventeenth century, illuminations depicting the life of the Virgin Mary in a small, one-sided sənsul (Walters, acc. no. 36.10) were painted without the use of guidelines.

The liturgical fans were also pricked and ruled prior to painting. On the blank versos of the Walters fan, one can see the prick marks and blind ruled lines that were used to lay out the figures and designs.[22] Horizontal lines established the boundaries for the wide decorative bands (härag), above and below the saints, that extend across the entire width of the fan. Prick marks that correspond with vertical lines in the center of each panel likely served as guides for the placement of each of the standing saints.

Healing scrolls were made according to different criteria than other Ethiopian manuscripts and were not pricked and ruled before writing or painting.

The Painting Process

Illuminations in the manuscripts made prior to the seventeenth century were sketched out first in blue paint and later covered over. However, this blue underdrawing was often left exposed to depict the hair and beards of elderly men.[23] In the sixteenth-century sənsul leaves (Walters, acc. nos. W.927‒929), a red ink was used for underdrawing. By the First Gondärine period, it was more common for a pale black ink to be used for underdrawing, such as in a Gondärine homiliary (Walters, acc. no. W.835) and a one-sided sənsul (Walters, acc. no. 36.10), both from the late seventeenth century. It is only during this later period, when professional artists collaborated with scribes in the production of lavishly illustrated manuscripts,[24] that certain images or compositions might be sketched first on scrap pieces of parchment or on the margins or blank pages of codices.[25] One example is seen in the Gondär Homiliary (acc. no. W.835) where a large angel, drawn in black ink on the front flyleaf (fol.1v), has similar features to the illumination of Saint Michael on folio 2v of the manuscript.[26] These same artists are known to have used model books for inspiration, both for the illuminations that they painted in manuscripts and for the icons and wall paintings that they also produced.[27]

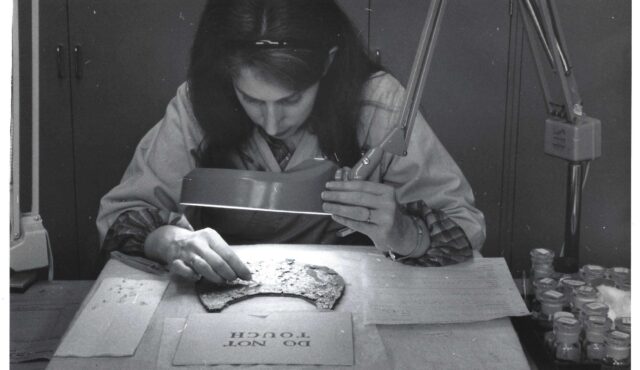

Sketches in black ink and partial text found on the reverse of a healing scroll

Healing Scroll, Ethiopia, 19th or 20th century, ink on parchment, 40 1/2 × 6 5/8in. (102.9 × 16.8 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Gift of Dr. Giraud and Carolyn Foster, 2021, acc. no. W.946, verso)

The figurative images and talismans of nineteenth- and twentieth-century healing scrolls were rapidly drawn in black ink and then colored with thin applications of paint. An interesting feature of a healing scroll in the Walters collection (19th‒20th century, Walters Art Museum, acc. no. W.946) is a group of overlapping sketches and partial text on the reverse of the bottom strip (fig. 1). Whether this piece of parchment served first as a blank canvas for the scribe, before the scroll was assembled and written, or the sketches were made and the text inscribed after the fact, perhaps by a scribe’s pupil, is unknown.[28]

Inks and Pigments for Writing and Illumination

Across all types, the analyzed manuscripts were found to have similar writing inks: a carbon-based black for the text and a cinnabar/vermilion ink for rubrication. A broad range of pigments were used for illumination, including indigo, smalt, vergaut (a mixture of indigo and orpiment), carbon black, copper-based greens, orpiment, organic yellow, cinnabar/vermilion, insect-based reds, iron-based earths, lead white, and calcium-based whites.[29]

Writing Inks

Carbon black, without phosphate,[30] was identified as the main writing ink in all but one of the manuscripts included in this study.[31] These results are not surprising, as the production of black inks was well known by scribes in Ethiopia. The literature on Ethiopian inks reveals a rich tradition of ink production that is characterized by the use of carbon black as the main component, with no mention of iron-gall ink (the most common ink used for writing outside Ethiopia).[32] However, the analysis of a codex that predates the fourteenth century showed that it was written with a mixed ink that included carbon black and iron.[33] At the same time, a single leaf from the same period contained no carbon black and only a plant-based ink that was rich in iron.[34] Carbon-containing materials like roasted plants, cereals, and other organic matter were used as ink ingredients, yet the primary source for the carbon black was soot, often collected from the bottoms of cooking pots or from lamps.[35] Tree gums such as gum Arabic, frankincense or, more recently, eucalyptus gum were used as binders for the ink.[36] These carbon-based inks were made into cakes and dried, so they could be stored for long periods and reconstituted with water when needed by the scribes.[37] The preparation process for these inks was extensive, often taking six months to a year before the ink was ready for use.

The inks of healing scrolls often contained several unusual materials, intended to make the prayers more effective and to ward off evil spirits. For example, some recipes included the horn of a black sheep and the hair of a black goat for black ink, while the bones of bulls were used for brown ink.[38] Red inks used to write important words and the name of the client might contain the sap of ritual plants or drops of blood from the animal sacrificed to make the parchment in order to increase the magic powers of the scroll.[39] Other ingredients of red inks used for healing scrolls and codices varied according to the practices of individual scribes but often included water, starch, and gums as binding media.[40]

Some contemporary scribes have described using the flowers and roots of certain native Ethiopian plants to produce a red writing ink.[41] However, the analysis of red inks in manuscripts from different periods has revealed the predominant use of cinnabar/vermilion to write important passages of text in liturgical manuscripts (i.e., rubrics), captions and other inscriptions, and an owner’s or donor’s name.[42] This practice continued until the eighteenth century when scribes gradually began using the synthetic red inks that were becoming commercially available.[43] A mercury-based ink associated with cinnabar/vermilion (mercury sulfide, HgS)[44] was identified in eight out of the sixteen manuscripts in the study.[45] Historically, the naturally occurring mineral cinnabar was sourced from mines in Almaden, Spain, as well as from regions like Altai and Turkestan, and its use as a coloring material dates back to Egyptian times. Notably, there are no known cinnabar mines or records of vermilion production in Ethiopia. Historical documents describe Ethiopia’s international trade via maritime routes across the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden with India, Egypt, and the Mediterranean regions as early as the first or second century CE.[46] However, it is almost impossible to confirm an exact source of cinnabar/vermilion due to the active involvement of Ethiopia in international trade from ancient times through the early modern period.

In addition to mercury-based inks, our analysis identified an iron-rich red ink that was used for the rubrication of a nineteenth- to twentieth-century healing scroll (Walters, acc. no. W.954). The use of earth pigments is a well established Ethiopian tradition, since a wide variety of earth colors were used for painting houses, dyeing clothing, decorating gravestones, and other applications.[47]

A notable finding was the use of a blue-green ink to write the text in a copy of the Homilies of Saint Michael that is dated to the 1770s (Melikian Collection, Melikian 389). Analysis using fiber optics reflectance spectroscopy (FORS) and x-ray fluorescence (XRF) identified this ink as vergaut—a green pigment produced by mixing indigo and orpiment.[48] Another possible example of this phenomenon is an eighteenth-century Miracles of Mary manuscript in the collection of the Princeton University Art Museum in which the main text was written with a blue-green ink.[49] Vergaut is known to have been used for the illumination of Ethiopian codices since at least the early fifteenth century (see pigment section below). The literature is lacking on the historical use of blue-green writing inks in Ethiopia, although one scholar has occasionally observed a blue writing ink in Ethiopian codices and attributed it to possible foreign influence.[50] Based on the current findings, the use of the indigo-orpiment mixture as a writing ink by later Ethiopian scribes lays the groundwork for future research into the possible uses of vergaut and trade influences. For example, one study documented the use of vergaut as a writing ink in a Turkish Islamic illuminated manuscript from the sixteenth century.[51] We cannot ignore the economic and political exchanges that happened in Ethiopia throughout centuries and how these could have had a significant impact on the source of materials and artistic influences in the production of Ethiopian manuscripts.

The findings from this study underscore the rich tradition and complexity of ink production in Ethiopian manuscripts. While carbon black remains the predominant component, the extensive use of imported cinnabar/vermilion and iron-rich pigments for red and brown inks and the unique application of vergaut for a blue-green ink demonstrate the diverse materials employed by Ethiopian scribes.

Pigments for Illumination

Black

Similar to the black ink for writing, the black pigment used for illumination in all examined manuscripts was identified as a carbon-based black without phosphate, known as soot or lampblack. This black pigment was primarily produced through carbonization, which involves burning grains, plants, and other organic materials. Soot, collected from cooking vessels or lamps, was another common source of this carbon black pigment.[52]

Blue

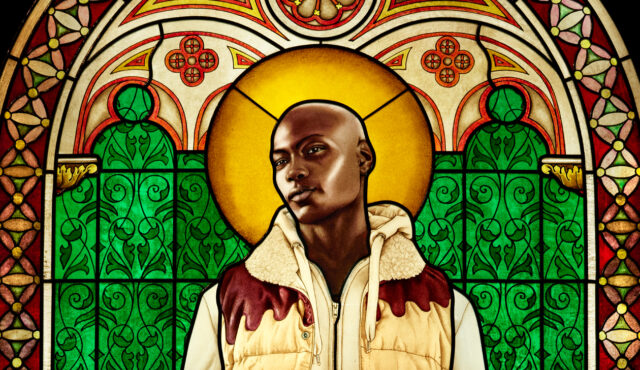

The main blue colorant used in fourteen of the examined manuscripts is indigo, demonstrating that it was continuously used from the fourteenth to the twentieth century.[53] Indigo is an organic colorant extracted from the indigo plant (Indigofera genus) that is indigenous to India; the colorant was exported since ancient times.[54] The species Indigofera tinctoria produced the best dye and was known as “Nila” or “Nil” in all Indian languages.[55] It was known by Ethiopians as nil in Gǝʿǝz, meaning a type of blue.[56] Indigo can vary in tone from dark blue to black and was often employed for both colors during this period (fig. 2), although carbon black was occasionally used on its own in a few manuscripts. Due to the specific FORS spectral features of indigo it was possible to identify it when used on its own, in mixtures with white pigments, and in mixtures with other pigments such as orpiment to produce vergaut.

Indigo was used as a blue-black in the decorative bands (harag) above and below the saints, and as a bright blue for their robes.

Folding Processional Icon in the Shape of a Fan, Ethiopia (Gundä Gunde), late 15th century, ink and paint on parchment, sinew and cotton thread, 24 1/4 × 154 1/8 × 4 3/4 in. (61.6 × 391.4 × 12 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 1996, acc. no. 36.9

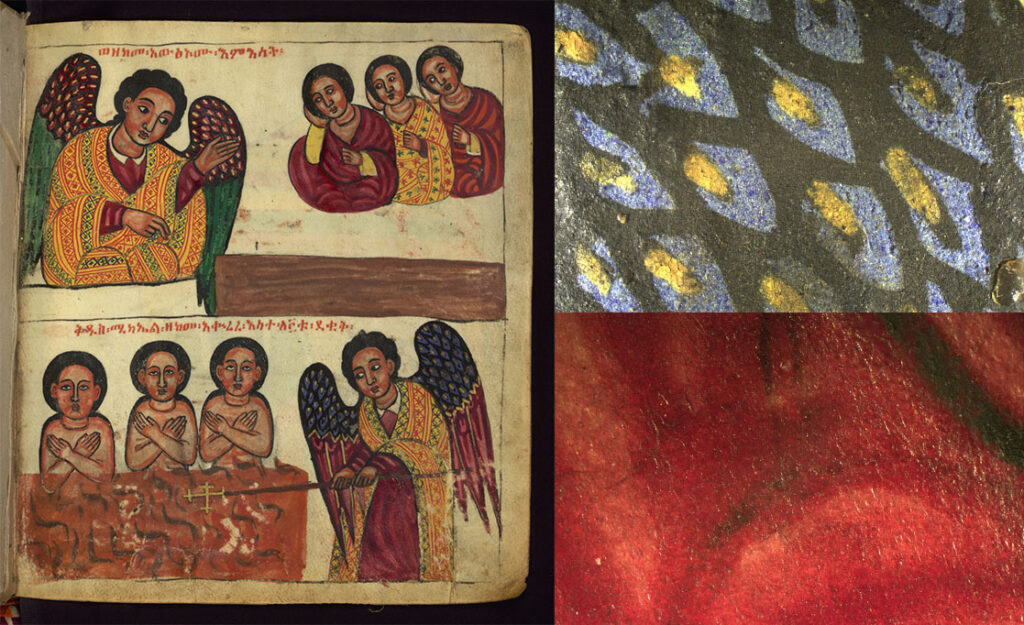

Beyond the prevalent use of indigo in Ethiopian manuscripts, XRF analysis revealed the presence of cobalt, nickel, arsenic, iron, and potassium in a bright blue color found throughout the Gondär Homiliary (Walters, acc. no. W.835) (fig. 3). The presence of a cobalt-containing blue pigment was confirmed by FORS.[57] These elements are associated with smalt,[58] a cobalt-based glassy pigment that was known in Europe since the sixteenth century. When cobalt is found with impurities such as nickel, arsenic, and iron, this indicates the presence of the mineral skutterudite (also known as smaltite).[59] Smalt was coarsely ground to retain its intense blue color. In seventeenth-century Europe, smalt was frequently used as a substitute for ultramarine blue and azurite.[60] At the same time, the presence of potassium can be linked to the production process of smalt, as potash served as a flux.[61] Despite its European origins, smalt was not unfamiliar in Ethiopian art, as documented in various studies.[62] Concurrent research on Ethiopian icon paintings at the Walters has confirmed the presence of smalt in one panel from the Second Gondärine period, which lasted from the late seventeenth through the nineteenth century (Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University, IESMus3703).[63]

Wings of the angel in the lower right showing smalt particles under 0.63x magnification (top right). Detail of the robes executed with a translucent lake pigment, made with an insect-based red, applied over an opaque layer of vermilion under 1x magnification (bottom right)

Zämänfäs Qǝddus (scribe), Gondär Homiliary, Ethiopia (Gondär), late 17th century, ink and paint on parchment, 10 × 9 1/16 in. (25.4 × 23 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 1996, acc. no. W.835, fol. 60r

By the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, coinciding with the presence of Jesuit missionaries in Ethiopia and increased international trade, new imported pigments began to appear in manuscript illumination. These included smalt and organic red lakes (see below),[64] signifying the integration of new foreign materials into traditional Ethiopian artistic practices.

Red

Recipes collected from contemporary scribes and artists list native plant materials and red earths as source materials for red inks and paint. However, previous scientific research has documented the extensive use of cinnabar/vermilion in Ethiopia as a writing and painting material.[65]A red mercury-based pigment (mercury sulfide, HgS), associated with cinnabar or vermilion, was found in thirteen of the studied manuscripts that dated from the fourteenth through the nineteenth century.[66] The pigment was employed on its own in bright red areas as well as in a variety of mixtures throughout this period. Cinnabar/vermilion was used to make a diversity of flesh tones and hues that are visible throughout the manuscripts. Interestingly, only the fourteenth-century manuscript that was examined had no pigment in the flesh areas, which were represented by bare parchment (Walters, acc. no. W.836).[67] In the other manuscripts, the various hues of flesh tones were achieved by mixing cinnabar/vermilion with white pigments, such as lead-based whites (e.g., lead white) and calcium-based whites (e.g., chalk), as well as with orpiment and white pigments. An organic carbon-based black pigment was added to this cinnabar/vermilion mixture to create the darker flesh tones observed in manuscripts from the Second Gondärine period. One study reported the use of this same mixture of pigments in an Ethiopian panel painting.[68]

The analytical results also revealed the presence of iron, which suggests the use of iron-based compounds such as earths and ochres (iron oxide) for painting. An exploration of the use of locally available red earth pigments, particularly their widespread use in healing scrolls, highlighted the practical and symbolic importance of these red pigments in Ethiopian culture.[69]

In addition to the inorganic red pigments, an organic red derived from insects, such as kermes or an Indian lac (Laccifer lacca), was found in at least two manuscripts from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, respectively.[70] In both cases the garments were painted with cinnabar/vermilion and then highlighted with a red insect-based lake pigment to indicate the shadows of the drapery folds (fig. 3). This is a well-known European technique that is commonly found in early modern panel paintings and illuminated manuscripts.[71] Insect-derived lake pigments, including lac, cochineal, and kermes had been imported into Ethiopia since ancient times. One scholar has described the historical practice of importing these red dyes through Harär.[72]

Yellow

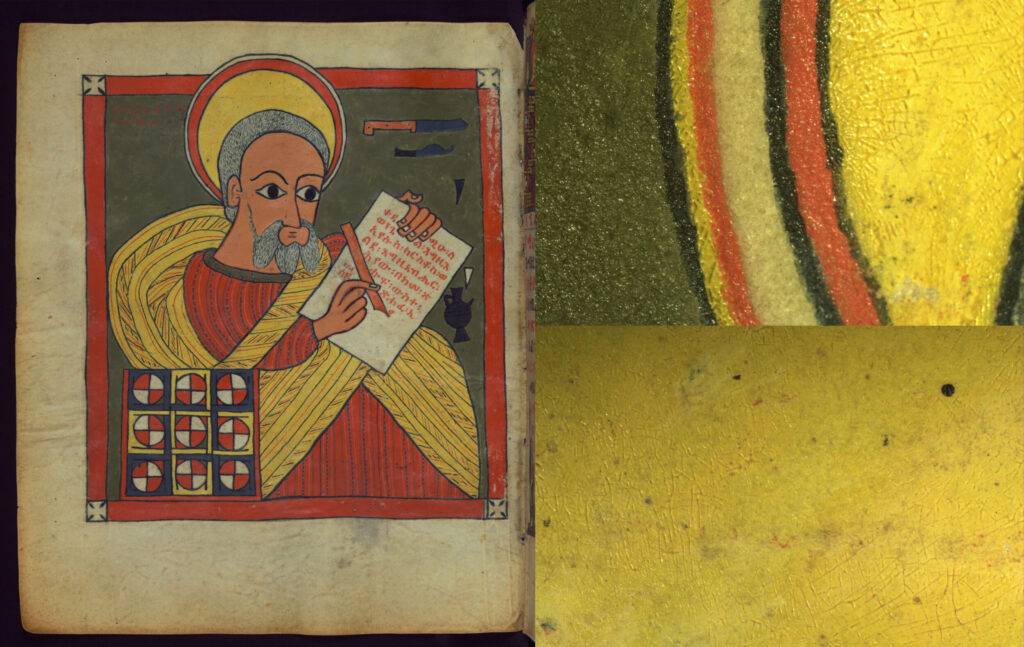

The manuscripts often incorporate bright yellows, in most cases orpiment (arsenic trisulfide, As2S3). Orpiment, like cinnabar/vermilion, is an ancient pigment that was likely imported into Ethiopia.[73] The seventeenth-century historian and collector Charles Jacques Poncet observed the importation of vermilion, “yellow arsenic” (orpiment), and other goods from Sudan.[74] The lamellar, or layered, structure of the mineral orpiment makes it difficult to grind into a powder; as a result, the pigment is quite coarse.[75] However, this coarse grade helped to preserve the intense yellow color and reflective properties of the pigment that together made it appear like gold. It is no wonder that, in the first century CE, Pliny referred to orpiment as “auripigmentum” or “auripigmento” (golden pigment). Orpiment was used on its own as well as in mixtures. It can be found alone in the backgrounds of illuminations, as well as in the garments and haloes of saintly figures (fig. 4). Complex mixtures of orpiment with red and white pigments were used for flesh tones, mixtures with red pigments produced an orange hue, and mixtures with indigo produced the green pigment known as vergaut.

Detail of the bright yellow orpiment or “king’s yellow” that was used to paint the Evangelist’s halo and cloak under 0.63x magnification (top and bottom right)

Gospel Book, Ethiopia, first half of the 16th century, ink and paint on parchment, 11 7/8 × 9 13/16 in. (30.2 × 25 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 1998, acc. no. W.850, fol. 60v

In comparison to medieval and early modern manuscripts from Europe and the Middle East, where ink made from powdered gold leaf was occasionally used for writing and gold leaf or paint more frequently for illumination, the precious metal is rarely found in Ethiopian manuscripts. This trend is also observed in Ethiopian icon paintings, where orpiment (also known as king’s yellow) was used instead of gold.[76] One unusual exception in manuscripts is a richly decorated copy of the Miracles of Mary that was completed in the royal scriptorium of Emperor Dawit II (r. ca. 1380‒1413) in December of 1400. Although unconfirmed by scientific analysis, gold appears to have been used extensively for the twelve portraits of the Virgin Mary and for her name in their inscriptions.[77] In the fourteenth- to fifteenth-century Kebran Gospels (Kebran Gabriel Ms. 1) a “dull and grainy reddish gold” is said to be used in a limited way for a few of the miniatures.[78] A third possible example is a late eighteenth-century miniature of the Virgin, inserted in a mid-seventeenth-century Miracles of Mary manuscript (British Library, BL Or. 641) that is said to bear traces of gold on Mary’s halo and garments.[79] To the authors’ knowledge, the only confirmed instance of gold in an Ethiopian manuscript is found in a copy of the Miracles of Mary (Brown University Library, Ms. Ethiopic 14–) that was produced at Gondär in ca. 1730 for an aristocratic client.[80] In the first miniature of the manuscript, which depicts Our Lady Mary and the Infant Christ and serves as a devotional image for the reader, the star on Mary’s blue cloak and the decoration on the collar of both Mary’s and Christ’s tunics are rendered in gold leaf (fig. 5). Recent research has shown that, since the late antique period, high-karat gold coinage was the source metal for the manufacture of gold leaf throughout the Mediterranean region.[81] At a certain point, the technology of gold beating might have been introduced in Ethiopia through cultural exchanges promoted by the emperor. However, the absence of domestically produced gold coinage by the mid-eighth century and the very limited quantity of foreign coins that remained in circulation makes this theory less plausible.[82] To create the elaborate illuminations of Dawit’s Miracles of Mary manuscript, and perhaps also the later two Miracles manuscripts from Gondär mentioned above, foreign craftsmen working at the court may have supplied imported gold leaf and also assisted in the gilding of the miniatures.[83] Despite how they were produced, the few examples given here are very rare. As seen in this study, most Ethiopian scribes and painters used orpiment instead of gold, likely finding that the pigment contributed a particular vibrancy that contrasted well with the saturated reds, greens, and blues of their palettes.

Gold leaf was used to depict the star on the Virgin’s cloak in a copy of the Miracles of the Virgin Mary (ca. 1730, Ms. Ethiopic 14–, fol. 10v, Brown University Library) (left). Detail of the gold star under magnification (right). (Credit: Täʾammərä Maryam = Miracles of Mary (1400), Brown Olio, Brown Digital Repository, Brown University Library). Detail photo by Lindsay Elgin

Interestingly, despite orpiment’s popularity, it was not found in any of the Ethiopian healing scrolls included in this study. FORS analysis revealed the presence of a flavonoid-type[84] organic yellow in one nineteenth-century scroll and two nineteenth- or twentieth-century scrolls from the Walters collection (fig. 6).[85] This pigment has likely faded with time and must originally have been more intensely colored. The presence of several organic pigments has been described in other studies of Ethiopian healing scrolls, and especially prominent is an organic yellow that remains to be securely identified.[86]

An unidentified organic yellow paint was used for Saint Michael’s collar, while the eyes and mouth of the Lion of Judah were painted with an iron-based earth pigment mixed with orpiment.

Scroll with the Lion of Judah, Ethiopia, 19th century, ink and paint on parchment, 59 7/16 × 3 7/16 in. (151 × 8.8 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Gift of Gene Guerny, 1997, acc. no. W.845

Two modern synthetic pigments, chrome yellow and chrome orange, were identified in two nineteenth-century healing scrolls.[87]

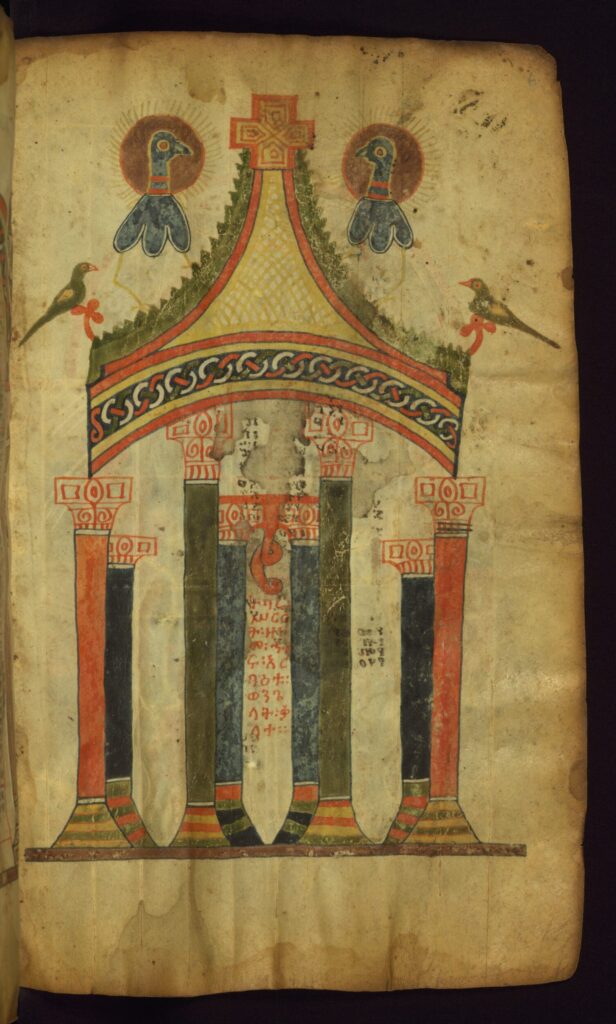

Orange

An orange paint was identified as a mixture of orpiment and cinnabar/vermilion in five manuscripts dating from the fourteenth to the eighteenth century (fig. 7).[88] This pigment mixture was found in the backgrounds, garments, and other parts of the illuminations.

In this diagram, an orange paint made from a mixture of cinnabar/vermilion and orpiment was used for some of the columns and the canopy. A brown paint, made from a mixture of vermilion and an iron earth, was identified in the haloes of the two birds.

Gospel Book, Ethiopia (Təgray), early 14th century, ink and paint on parchment, 10 1/2 × 6 11/16 × 4 1/2 in. (26.7 × 17 × 11.4 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 1996, acc. no. W.836, fol.6r

Green

Research into Ethiopian manuscripts has identified at least two different types of green pigments: verdigris, a copper-based green pigment that was manmade, and vergaut, a mixture of indigo and orpiment. In four of these examples,[89] both green pigments were used in specific areas, with vergaut typically found in the background and in decorative elements of the miniatures (fig. 8). For instance, in a fifteenth-century sənsul (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, acc. no. 2012.301) where the saints are depicted on a red background, vergaut was identified in the light green capes and mixed with verdigris in the darker green capes.

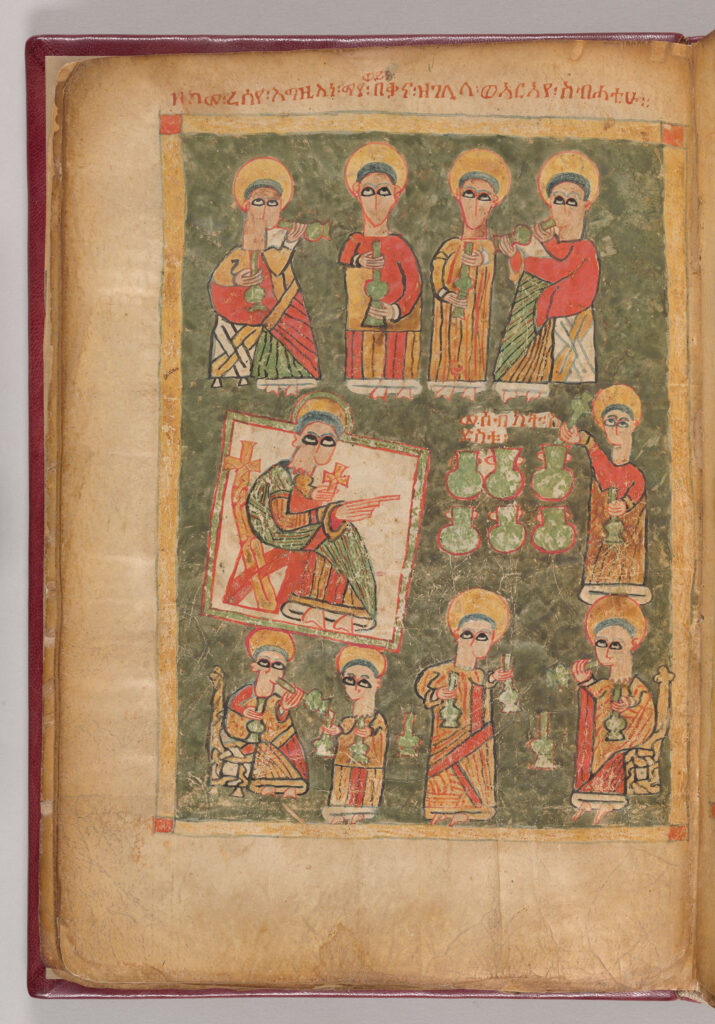

The background of this miniature was painted with vergaut, a mixture of indigo and orpiment, while the flasks were executed with a copper green paint, most likely verdigris.

Zir Ganela Gospels, Ethiopia, 1400‒1401, tempera on parchment, 14 1/4 × 9 7/8 in. (36.2 × 25.1 cm). The Morgan Library and Museum, New York, Purchased on the Lewis Cass Ledyard Fund, 1948, acc. no. M.828, fol. 10v

Vergaut was found to be used on its own in eight of the manuscripts discussed here, including manuscripts from the Walters collection and four loans.[90] With the exception of the fifteenth-century sənsul mentioned above, vergaut was found exclusively in the background of the illuminations. The color green holds significant meaning in Ethiopian society, representing richness, fertility of the land, and hope. This might explain the extensive use of the color, particularly in cases where the entire background was covered in green, as well as in the garments of saints and other religious figures.

In a study of the origin and uses of color names in Ethiopia, the Gǝʿǝz term ħamalmil is said to be associated with green hues.[91] This term is traced back to a passage in Psalms 67:14, ba-hamalmāla warq meaning “in green of the gold.”[92] The pairing of green and gold in Psalms 67:14 emphasizes wealth, glory, and divine beauty. One can only wonder if this connection might have influenced the use of green pigments in Ethiopian manuscripts, enriching the symbolic language of the artists’ craft.

In addition to the two green pigments described above, a green earth was found in two healing scrolls from the nineteenth‒twentieth century in the collection of the Musée du quai Branly.[93] However, no green earth pigment was identified in any of the manuscripts analyzed in this study.

White

In the earliest manuscripts, instead of using a white pigment, the natural color of the parchment was reserved to represent white areas of the miniatures (Walters, acc. nos. W.836 and W.839).[94] However, by the late fourteenth century, scribes began using lead white (lead carbonate, PbCO3) selectively on its own and in mixtures. Examples include a mixture of lead white with vermilion for a pale pink shroud found in a Gospel book leaf of this period, as well as a mixture of lead white, vermilion, and orpiment for the flesh tones (Walters, acc. no. W.839). A slightly more complex mixture, including lead white, vermilion, orpiment, and iron earth, was found in the flesh tones of three manuscripts from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (Morgan, MS M.828; Walters, acc. nos. W.850 and W.927).

Detail of the Virgin’s face, showing a mixture of cinnabar/vermilion, anhydrite, and a small amount of orpiment under 0.63x magnification

Virgin and Child from Gondärine Sənsul, Ethiopia (Gondär), late 17th century, ink and paint on parchment, extended 3 × 23 in. (7.62 × 58.42 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 1996, acc. no. 36.10, fol. 3r

In one early example (1480‒1520, J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 105 [2010.17]), anhydrite (calcium sulfate, CaSO4) was used on its own and together with lead white for white areas. In a near contemporary manuscript (1504‒1505, J. Paul Getty Museum, no. Ms. 102 [2008.15]), anhydrite was again used on its own and in a mixture with vermilion to make an orange paint. In a seventeenth-century Gondärine sənsul (Walters, acc. no. 36.10), anhydrite was found mixed with cinnabar/vermilion and a small amount of orpiment for the flesh tones (fig. 9). To make a gray paint in two First Gondärine manuscripts, anhydrite was either mixed with indigo (Walters, acc. no. W.835) or with carbon black (Walters, acc. no. 36.10). The use of anhydrite is not surprising since there are records of large deposits of anhydrite in the sedimentary formations of the Red Sea coastal areas, the Danakil Depression, and the regions of Ogaden, Shewa, Gojjam, Təgray, and Hararghe. In addition to anhydrite, another calcium-based pigment (likely calcium carbonate or chalk) was found in two manuscripts from the Second Gondärine period (Melikian 389 and Walters, acc. no. W.835). In Melikian 389, the calcium-based white was used alone as a white pigment, while in Walters, acc. no. W.835, the white pigment was mixed with cinnabar/vermilion and a little orpiment for the flesh tones. Although the sources for anhydrite and chalk can be traced to Ethiopia, the source of lead white, as well as the facts related to its production, remains undocumented.

Brown

In a nineteenth-century healing scroll (Walters, acc. no. W.845), an unusual brown paint was found to be a mixture of an unidentified organic colorant with a lead-based pigment (probably lead white). A different brown paint was found in a fifteenth-century codex and a sənsul from the same period (Morgan, MS M.828, and Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, acc. no. 2012.301). In these examples, XRF analysis confirmed the presence of iron, which can be associated with a brown earth such as a burnt sienna or an iron oxide. Finally, a mixture including cinnabar/vermilion, orpiment, iron earth, and a copper-based pigment was found in the brown soil of a miniature in a manuscript from the Second Gondärine period (Melikian 389).

Conclusions

This study on the diversity of Ethiopian manuscripts, including codices, sənsuls, liturgical fans, and healing scrolls, reflects Ethiopia’s sustained historical engagement with written culture. Each manuscript type showcases unique artistic and functional characteristics, emphasizing the integral role of spirituality in Ethiopian culture. For instance, ancient codices like the Abba Gärima Gospels highlight the early adoption of illuminated texts for religious practice, while sənsuls and liturgical fans demonstrate innovation in format and design to support devotional and liturgical purposes. Healing scrolls, deeply personalized and tied to Ethiopian Orthodox beliefs, underscore the interplay between faith, superstition, and magic practices.[95]

These findings offer a deeper understanding of the cultural and international influences that shaped the production of Ethiopian manuscripts, illustrating the intricate network of trade and knowledge exchange that informed this ancient practice. The analysis of a relatively large number of manuscripts in various formats identified clear paths of artistic innovation and local resource applications, such as the production and use of carbon-based ink and anhydrite. Incorporating smalt and insect-based red colorants into seventeenth- and eighteenth-century manuscript illumination exemplifies the dynamic fusion of local and global influences. Ethiopian scribes adeptly integrated imported pigments into traditional artistic practices, creating manuscripts of transcultural artistry. The pigments identified in this study are the material manifestation of artistic intention and the importance of color for the Ethiopian orthodox community. Each one reflects a conscious choice that is rooted in meaning, belief, and identity, making color an essential medium to express cultural continuity, spiritual devotion, and artistic innovation.

This research also opens avenues for further investigation, particularly regarding the limited use of gold leaf and powdered gold and the production and utilization of lead white. It is important to note that most of the ink and paint recipes collected since the mid-twentieth century are considered modern, with no traditional recipes recorded to the authors’ knowledge.[96] Except for those that describe the preparation of earth colors, these recipes predominantly mention pigments of organic origin. However, our study demonstrated that not all pigments used in historical manuscripts are organic in origin.

Overall, this study underscores the complexity and richness of Ethiopian manuscript production, highlighting the significant impact of both local traditions and international exchanges. Continued research is necessary to fully understand the diverse materials and techniques employed in this unique artistic tradition.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Roger Williams, Head of Libraries Conservation at Brown University and the John Carter Brown Library, for his assistance in providing information about the Miracles of Mary manuscript (Brown University Library, Ms. Ethiopic 14–) and for confirming that gold was only used in the prefatory miniature of the Virgin and Child on folio 10v. We also thank Nancy Turner, Conservator of Manuscripts at the J. Paul Getty Museum, for detailed information about the three Ethiopic manuscripts in their collection and for sharing her research on the uses of gold in Western manuscripts.

[1] Ethiopia at the Crossroads, a traveling exhibition co-organized by and presented at The Walters Art Museum from December 3, 2023, to March 3, 2024; the Peabody Essex Museum from April 13 to July 7, 2024; and the Toledo Museum of Art from August 17 to November 10, 2024.

[2] Quandt’s initial findings are reported in Karen French, Hae Min Park, Abigail Quandt, and Glenn Gates, “Technical Research on a Selection of Ethiopian Manuscripts and Panel Paintings in the Walters Art Museum,” in Ethiopia at the Crossroads, ed. Christine Sciacca (Walters Art Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2023), 267‒79. Additional details are found in Abigail B. Quandt, “A Living Tradition: An Introduction to the Production and Use of Orthodox Christian Manuscripts in Ethiopia from the Pre-Modern Era to the Present Day,” in Care and Conservation of Manuscripts, ed. Matthew James Driscoll, vol. 19, Proceedings of the Nineteenth International Seminar Held at the University of Copenhagen, 19–21 April 2023 (Museum Tusculanum Press, 2025).

[3] Judith S. McKenzie and Francis Watson, The Garima Gospels: Early Illuminated Gospel Books from Ethiopia (Manar al-Athar, University of Oxford, 2016), 31–41. See also Alessandro Bausi, “The ‘True Story’ of the Abba Gärima Gospels,” Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies Newsletter 1 (2011): 17–20, https://www.fdr.uni-hamburg.de/record/613.

[4] Despite the carbon dating results of two parchment fragments from the manuscript, many art historians question whether the illuminations of the Abba Gärima Gospels can be assigned such an early date based upon stylistic grounds. Christian Sciacca, personal communication, 2023.

[5] Unpublished analytical reports of two Gospel books (ca. 1504–1505, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 102 [2008.15] and ca. 1480–1520, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 105 [2010.17]), a single leaf from an early Gospels (late 14th–early 15th century, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 89 [2005.3]), and a Miracles of Mary manuscript (ca. 1730, Brown University Library, Ms. Ethiopic 14–) that were generously shared with the authors provided further data for comparison with our own results.

[6] Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, “Sənsul,” in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica 4, ed. Alessandro Bausi and Siegbert Uhlig (Harrassowitz, 2010), 625–26.

[7] Some sənsuls bore both text and images in a horizontal orientation, with pictures on one side and text on the other. Denis Nosnitsin, “Ethiopian Manuscripts and Ethiopian Manuscript Studies: A Brief Overview and Evaluation,” Gazette du livre médiéval 58 (2012): 1–16, at 5.

[8] A seventeenth-century sənsul (Walters Art Museum, acc. no. 36.10) has an inscription by the owner that threatens excommunication to any individual who might steal or erase the manuscript.

[9] The pocket-sized sənsuls measure about 10–12 cm square when closed, while an especially large seventeenth-century example of an accordion-folded book thought to be a sənsul measures 24.5 cm high by 17 cm wide (Private collection).

[10] Three fragmentary leaves survive from a late fifteenth- to early sixteenth-century sənsul (Walters Art Museum, acc. nos. W.927, W.928, and W.929) yet only one (W.927) was analyzed due to time constraints.

[11] Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, “Märäwǝḥ,” in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica 3, ed. Siegbert Uhlig (Harrassowitz, 2007), 775–77.

[12] Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, “The Liturgical Fan and Some Recently Discovered Ethiopian Examples,” Rocznik Orientalistyczny 57, no. 2 (2005): 19–46.

[13] Sevir Chernetsov, “Magic Scrolls,” in Uhlig, Encyclopaedia Aethiopica 3, 642–43, at 642.

[14] Smaller and narrower scrolls were rolled up inside a leather case and worn, while wider and longer examples were usually hung on a wall inside the home or over the owner’s bed.

[15] Eyob Derillo, “Text and Image: Magic Scrolls and Recipe Books as Part of the Healing Culture of Ethiopia,” in Sciacca, Ethiopia at the Crossroads, 321–25.

[16] Derillo, “Text and Image,” 323–24.

[17] Jacques Mercier, Art That Heals: The Image as Medicine in Ethiopia (Museum for African Art, 1997), 60 and fig. 49.

[18] For the ruling in W.839, see French et al., “Technical Research,” 268, fig. 1. Guidelines for the illumination are also found in three early Gospel books (Morgan, MS M.828; Getty, Ms. 105 [2010.17]; and Getty, Ms. 102 [2008.15]).

[19] In another Gospel book (Getty, Ms. 102) indentations at the center of the haloes on the obverse of the illuminated folios indicate that a compass was used but no hole was created. In a fifteenth-century miniature of the Virgin and Child that was inserted into an eighteenth-century manuscript, prick holes and indented circles found on the verso of the folio indicated that “the halos of both figures were marked out with calipers.” Jacek Tomaszewski, Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, and G. Z. Żukowska, “Ethiopian Manuscript Maywäyni 041 with Added Miniature: Codicological and Technological Analysis,” Annales d’Éthiopie 29 (2014): 104.

[20] Christine Sciacca, “A ‘Painted Litany’: Three Ethiopian Sensul Leaves from Gunda Gunde,” The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 73 (2017): 92–95, https://journal.thewalters.org/wp-content/uploads/JWAM_73.pdf.

[21] Similar ruling lines are seen on the blank reverse of a fragmentary early sixteenth-century sənsul (Museum Fünf Kontinente, Munich, acc. no. 86-307 643) that is closely related to the three Walters sənsul leaves from Gundä Gunde. See Christine Sciacca, “Exploring Sensuls: An Indigenous Manuscript Tradition in Ethiopia,” The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 76 (2023), fig. 10, https://journal.thewalters.org/volume/76/essay/exploring-sensuls-an-indigenous-manuscript-tradition-in-ethiopia/.

[22] In photographs of the blank reverse of the liturgical fan from the monastery at Däbrä Ṣəyon, one can see both vertical and horizontal incised ruling lines that were made for the illumination.

[23] This practice is seen in the older saints of the Walters liturgical fan (acc. no. 36.9) and in the Evangelists depicted in three near-contemporary codices (Getty, Ms. 105; Getty, Ms. 102; and Walters, acc. no. W.850), all of which are attributed to the monastery of Gundä Gunde. For the Walters fan, see French et al., “Technical Research,” 273, fig. 4A.

[24] In manuscripts of the Miracles of the Virgin Mary that were produced during the Gondärine period, “the artist who executed the paintings and the scribe who copied the story were almost always different people.” Wendy Laura Belcher, Jeremy R. Brown, Mehari Worku, Dawit Muluneh, and Evgeniia Lambrinaki, “The Ethiopian Stories about the Miracles of the Virgin Mary (Täʾammərä Maryam),” in Sciacca, Ethiopia at the Crossroads, 304.

[25] Some of these sketches may have been executed by novice artists as they copied designs from model books. Belcher et al., “Miracles of Mary,” 304.

[26] For the sketch on fol. 1v and the finished illumination on fol. 2v of the Gondär Homilary, see The Walters Ex Libris, https://manuscripts.thewalters.org/viewer.php?id=W.835#page/4/mode/2up.

[27] A group of seventeenth-century sketches of religious compositions typically found in Gondärine manuscripts and icons were drawn in black ink on both sides of a fragmentary bifolio from an Ethiopian manuscript whose text had been erased (Victoria and Albert Museum, Prints and Drawings Collection, E.3937-1920, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O205572/st-george-and-the-dragon-drawing/).

[28] It is likely that the scroll was disassembled and the upper portion of this strip was cut off because the text on the front, which was written for the original client, was not relevant to a later owner.

[29] The analysis of two single manuscript leaves, Walters, acc. nos. W.839 and W.927, was performed by former Walters Conservation Scientist Dr. Glenn Gates using Raman spectroscopy, x-ray fluorescence (XRF) and fiber optics reflectance spectroscopy (FORS). The analysis of the remaining manuscripts in this study was conducted by Dr. Annette Ortiz Miranda, Walters Conservation Scientist, using XRF and FORS. The same experimental parameters were used in both studies. XRF was applied for elemental analysis with a Bruker ARTAX XRF spectrometer equipped with an Xflash detector; data processing was completed using software version 7.1. Spot collection was acquired with a rhodium source at 50 kV, 250 μA, and 120 s with a 1.0 mm diameter collimator under environmental conditions. FORS measurements were performed with a FieldSpec 4 fiber optic spectroradiometer (Malvern Panalytical-ASD Inc., CO). Spectra were collected over the range of 350–2500 nm (UV–vis-NIR), with a spectral sampling of 1.4 nm to 2 nm. The spectral resolution was 3 nm at 700 nm, and 10 nm at 1400 nm and 2100 nm. Measurements were carried out using a bifurcated fiber optic probe; each of the bifurcated ends is composed of 78 fibers and all 156 fibers (core 2000 μm in diameter) are well mixed in the common end. The sampling spot was 4 mm in diameter, and 60 spectra were averaged for each sample. The instrument was calibrated using a white reference panel from ASD, which is made of a totally reflective material.

[30] Despite the complexity of Ethiopian recipes for black inks, the components consisted of just carbon and oxygen, neither of which can be detected with XRF. Black inks made in later periods by other cultures were composed of carbon black treated with phosphate and are detectable with XRF. Carbon black without phosphate is known as soot or lampblack.

[31] A unique exception is the use of a blue-green ink for the text of a Homilies of Saint Michael (1770s, Melikian Collection, Melikian 389), the identification of which is discussed below.

[32] Of the hundreds of recipes collected by scholars in Ethiopia, the majority were for the manufacture of black ink, the essential medium for the copying of religious texts. Sergew Hable Selassie, Bookmaking in Ethiopia (pub. by author, 1981), 14; Éric Godet, “Une méthode traditionnelle de préparation de l’encre noir en Éthiopie,” Abbay 11 (1980–1982): 211–17; Sean Michael Winslow, “Ethiopian Manuscript Culture: Practices and Contexts” (PhD diss., University of Toronto, 2015), 175–89; Denis Nosnitsin and Ira Rabin, “A Fragment of an Ancient Hymnody Manuscript from Mǝʾǝsar Gʷǝḥila (Tǝgray, Ethiopia),” Aethiopica 17 (2014): 65–77, at 75–76, https://doi.org/10.15460/aethiopica.17.1.

[33] Alessandro Bausi, Antonella Brita, Marco DiBella, Denis Nosnitsin, Nikolas Sarris, and Ira Rabin, “The Aksumite Collection or Codex Σ (Sinodos of Qǝfrǝyā, MS C3-IV-71/C3-IV-73, Ethio-SPaRe UM-039): Codicological and Palaeographical Observations. With a Note on Material Analysis of Inks,” Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies Bulletin 6, no. 2 (2020): 127–71, at 151–58, http://doi.org/10.25592/uhhfdm.8470.

[34] Denis Nosnitsin, Emanuel Kindzorra, Oliver Hahn, and Ira Rabin, “A ‘Study Manuscript’ from Qäqäma (Tǝgray, Ethiopia): Attempts at Ink and Parchment Analysis,” Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies Newsletter 7 (2014): 28–31, http://doi.org/10.25592/uhhfdm.593.

[35] The Gəʿəz word for ink is maya hemmat or “water (or juice) of soot.” Winslow, “Ethiopian Manuscript Culture,” 174. See also Anaïs Wion, “An Analysis of 17th-Century Ethiopian Pigments,” in The Indigenous and the Foreign in Christian Ethiopian Art: On Portuguese-Ethiopian contacts in the 16th–17th Centuries, ed. Manuel João Ramos and Isabel Boavida (Ashgate, 2004), 103–112; Patricia Irwin Tournerie, Colour and Dye Recipes of Ethiopia (New Cross Books, 2010), 116; and Weronika Liszewska and Jacek Tomaszewski, “Analysis and Conservation of Two Ethiopian Manuscripts on Parchment from the Collection of the University Library in Warsaw,” in Care and Conservation of Manuscripts, ed. Matthew James Driscoll,vol. 15, Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Seminar Held in the University of Copenhagen 2nd–4th April 2014 (Museum Tusculanum Press, 2016), 183–201.

[36] Winslow, “Ethiopian Manuscript Culture” 175–78.

[37] The ink cakes were individually wrapped in pieces of parchment (ideally placed hair side facing in) so that they would not stick to each other while in storage. Godet, “Une méthode traditionnelle de préparation de l’encre noir en Éthiopie,” 216.

[38] Tournerie, Colour and Dye, 118–126.

[39] Jacques Mercier, Ethiopian Magic Scrolls (Braziller, 1979), 17.

[40] Tournerie, Colour and Dye, 104–126; Monia Vadrucci et al., “The Ethiopian Magic Scrolls: A Combined Approach for the Characterization of Inks and Pigments Composition,” Heritage 6, no. 2 (2023): 1378–96.

[41] Taye Wolde Medhin, “La préparation traditionnelle des couleurs en Éthiopie,” Abbay 11 (1980–1982): 220–21; Winslow, “Ethiopian Manuscript Culture,” 190–91; Mercier, Ethiopian Magic Scrolls, 18; John Mellor and Anne Parsons, “Manuscript and Book Production in South Gondar in the Twenty-First Century,” in Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on the History of Ethiopian Art Addis Ababa, 5-8 November 2002, ed. Birhanu Teferra and Richard Pankhurst (2003), 192.

[42] Nosnitsin et al., “A ‘Study Manuscript’,” 29; Wion, “17th-Century Ethiopian Pigments,” 105; Liszewska and Tomaszewski, “Two Ethiopian Manuscripts,” 193.

[43] The plants described by some modern scribes were difficult to obtain and process, so it is not surprising that the majority preferred to use commercially available red inks, especially given the small quantity that was needed to rubricate most types of manuscripts. Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, Alessandro Bausi, Claire Bosc-Tiessé, and Denis Nosnitsin, “Ethiopic Codicology,” in Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies: An Introduction, ed. Alessandro Bausi et al. (COMSt, 2015), 156; Magdalena Krzyżanowska, “Contemporary Scribes of Eastern Tigray (Ethiopia),” Rocznik Orientalistyczny 68, no. 2 (2015): 73–101, at 87.

[44] The distinction between the mineral cinnabar and the synthetic pigment vermilion, its artificial equivalent, can only be made with samples taken from the manuscript. As sampling was not permitted, non-invasive methods of analysis were solely used for this study.

[45] Due to time constraints, the red writing inks were not analyzed in all manuscripts.

[46] Marilyn Heldman with Stuart C. Munro-Hay, African Zion: The Sacred Art of Ethiopia (Yale University Press in association with Inter-Cultura, Fort Worth; the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, and the Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa, 1993), 117; Richard Pankhurst, “Across the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden: Ethiopia’s Historic Ties with Yemen,” Africa 57, no. 1 (2002): 303–419; and Mengistie Zewdu Tessema and Wondemeneh Adera Ayalew, “Some Factors Affecting the Prosperity of Trade in Ethiopia, 14th–18th Centuries,” Cogent Arts & Humanities 11, no. 1 (2024): 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2024.2335783.

[47] Winslow, “Ethiopian Manuscript Culture,” 190; Tournerie, Colour and Dye, 127–28; Vadrucci et al., “Ethiopian Magic Scrolls,” 1378–96.

[48] The FORS reflectance spectrum characteristic of vergaut includes reflectance features of a green pigment but with the absorption maximum of indigo near 660 nm and a shift of indigo’s inflection point from 720 nm to 715 nm due to the presence of the yellow pigment (orpiment). XRF analysis confirmed the identification of orpiment due to the detection of arsenic.

[49] Illuminated Devotional Manuscript (Artist and scribe unidentified, 18th century, Princeton University Art Museums, acc. no. y1951-28), https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/42128. The blue-green writing ink of the Princeton manuscript bears a striking resemblance to the vergaut ink of Melikian 389, yet its composition has not been confirmed by scientific analysis.

[50] Alessandro Bausi, “La tradizione scrittoria etiopica,” Segno e Testo 6 (2008): 540. The vergaut ink identified in Melikian 389 has a decidedly blue cast, so it is possible that this type of ink was used more frequently but not recognized as a blue-green mixture by scholars of Ethiopian manuscripts.

[51] Vinka Tanevska, Irena Nastova, Biljana Minčeva-Šukarova, Orhideja Grupče, Melih Ozcatal, Marijana Kavčić et al., “Spectroscopic Analysis of Pigments and Inks in Manuscripts: II. Islamic Illuminated Manuscripts (16th–18th Century),” Vibrational Spectroscopy 73 (2014): 127–37.

[52] Before the Gondärine period, scribes decorated the manuscripts that they copied and used the same black ink for both writing and illumination. To the authors’ knowledge, only three recipes for a carbon black paint used by professional artists have been recorded. The ingredients and methods of preparation are essentially the same as those for black writing inks. Medhin, “La préparation traditionnelle des couleurs en Éthiopie,” 219–220.

[53] Walters, acc. nos. W. 835, W.836, W.839, W. 840, W. 850, W. 927, W. 947, W.954, 36.9, and 36.10; Morgan, MS M.828; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, acc. no. 2012.301; Peabody Essex Museum, acc. no. E67892; and Melikian 389.

[54] The concentrated liquid was formed into cakes and dried. The cakes were small, lightweight, and easy to transport, and could be stored for many years before being reconstituted with water.

[55] Padmini Tolat Balaram, “Indian Indigo,” in The Materiality of Color: The Production, Circulation, and Application of Dyes and Pigments, 1400‒1800, ed. Andrea Feeser, Maureen Daly Goggin, and Beth Fowkes Tobin (Routledge, 2012), 139‒154, at 141.

[56] Tournerie, Colour and Dye, 42–43.

[57] FORS results confirmed the presence of cobalt-based smalt in folio 60r due to the intense absorption band in the 550–650 nm, structured in three sub-bands around 550, 600, and 640 nm.

[58] Smalt is a widely used term for a cobalt-doped glass; the word smalt comes from the Italian term smaltare (to melt).

[59] Skutterudite, found in Skutterud, Norway, was historically the principal source of cobalt. Nicholas Eastaugh, Valentine Walsh, Tracey Chaplin, and Ruth Siddall, Pigment Compendium: A Dictionary of Historical Pigments (Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004), 345.

[60] Bruno Mühlethaler and Jean Thissen, “Smalt,” Studies in Conservation 14, no. 2 (1969): 47–61, https://doi.org/10.2307/1505347; Annegret Marx, “Indigo, Smalt, Ultramarine—A Change of Blue Paints in Traditional Ethiopian Church Paintings in the 19th Century Sets a Benchmark for Dating,” in Ethiopian Studies at the End of the Second Millenium: Proceedings of the XIVth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, November 6‒11, 2000, Addis Ababa (Addis Ababa University, Institute of Ethiopian Studies, 2002), 1:215‒32.

[61] A flux is a material that helps reduce the melting point of silica, making it easier to work with at lower temperatures. Using potash as a flux in glassmaking refers to adding potassium carbonate (K₂CO₃), commonly derived from wood ash, to the glass mixture to lower the melting temperature of the silica (SiO₂), which is the primary component of glass.

[62] Fritz Weihs, “Some Technical Details Concerning Ethiopian Icons,” in Religiöse Kunst Äthiopiens / Religious Art of Ethiopia, ed. Walter Raunig, 303; Anaïs Wion, “17th-Century Ethiopian Pigments”, 107; Marx, “Indigo, Smalt, Ultramarine.”

[63] See Karen French’s note in this volume, “Ethiopian Icon Painting Practices: Examination and Technical Research on a Selection of Paintings.”

[64] Lakes are organic pigments that are prepared by the precipitation of a dye on a powdered, inorganic substrate. Many natural dyes were made into lake pigments, such as cochineal, kermes, madder, and lac, and used as paints and inks.

[65] Medhin, “La préparation traditionnelle des couleurs en Éthiopie,” 220‒21; Stanislaw Chojnacki, “Two Ethiopian Icons,” African Arts 10, no. 4 (1977): 44‒47, 56‒61, 87, https://doi.org/10.2307/3335143; Erica E. James, “Technical Study of Ethiopian Icons, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution,” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 44, no. 1 (2005): 39‒50; Tomaszewski et al., “Ethiopian Manuscript Maywäyni 041,” 106 and fig. 13; Wion, “17th-Century Ethiopian Pigments,” 105.

[66] Walters, acc. nos. W. 835, W.836, W.839, W.845, W.850, W.927, W.947, W.954, 36.9, and 36.10; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, acc. no. 2012.301; Peabody Essex Museum, acc. no. E67892; and Melikian 389.

[67] The same is true for an early Gospel leaf on loan to the exhibition (late 14th–early 15th century, J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 89 [2005.3]).

[68] Jacek Tomaszewski, “A Painted Panel of the Crucifixion Preserved in the Agwäza Church (Tǝgray): Technical Analysis and Preservation Strategies,” Rassegna di Studi Etiopici 3rd ser., vol. 7 (2023): 99–117, at 105.

[69] Tournerie, Colour and Dye, 126‒27. In a study of four nineteenth- to twentieth-century healing scrolls, red earth pigments were found to be mixed with vermilion or an unidentified organic colorant. Vadrucci et al., “Ethiopian Magic Scrolls,” 1391. In another study of eleven scrolls, the red paint in one example consisted only of iron oxide. Pascale Richardin, Jacques Mercier, Gabrielle Tiêu, Stéphanie Legrand-Longin, and Stéphanie Elarbi, “Les rouleaux protecteurs éthiopiens d’une donation au Musée du quai Branly. Etude historique, scientifique et interventions de conservation-restauration,” Technè 23 (2006): 79–84, at 81.

[70] Walters, acc. no. W.835, and Melikian 389.

[71] Jo Kirby, Maarten van Bommel, and André Verhecken, Natural Colorants for Dyeing and Lake Pigments: Practical Recipes and Their Historical Sources (Archetype Publications in association with CHARISMA, 2014), 9.

[72] Tournerie, Colour and Dye, 46.

[73] An eleventh-century Arabic scholar wrote that orpiment came from the Pontus area of Türkiye, Armenia, and Iraq. See Elisabeth West FitzHugh, ed., “Orpiment and Realgar,” in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics (National Gallery of Art, 1997), 47–79, at 54.

[74] Charles Jacques Poncet, A Voyage to AEthiopia, Made in the Years 1698, 1699, and 1700: Describing Particularly That Famous Empire; as Also the Kingdoms of Dongola, Sennar, Part of Egypt, &c. With the Natural History of Those Parts (London, 1709), 27–28.

[75] FitzHugh, “Orpiment and Realgar,” 54.

[76] See Karen French’s note in this volume.

[77] An Ethiopian miracle recounted in the Täʾammərä Maryam, or Miracles of Mary, attests to the use of gold ink in the production of a deluxe copy of the text for Emperor Dawit II. This may be the same manuscript described here. Other examples of the rare uses of gold in Ethiopian manuscripts are discussed in Winslow, “Ethiopian Manuscript Culture,” 191–200. See also Heldman, African Zion, 91–92; Balicka-Witakowska et al., “Ethiopic Codicology,” 156–57; Belcher et al., “Miracles of Mary,” 300.

[78] Heldman, African Zion, 179; Winslow, “Ethiopian Manuscript Culture,” 198, fig. 5.7.

[79] Jonas Karlsson, Jacopo Gnisci, and Sophia Dege-Muller, “A Handlist of Illustrated Early Solomonic Manuscripts in British Public Collections,” Aethiopica 26 (2023), 159–225, at 163 and 195–97, https://doi.org/10.15460/aethiopica.26.

[80] In 2014, Michele Derrick, Conservation Scientist, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, conducted scientific analysis of two illuminations in the manuscript. XRF confirmed the identification of gold in the star on the Virgin’s cloak on folio 10v. An unpublished description and suggested dating of the manuscript by Marilyn E. Heldman was kindly shared with the authors by William S. Monroe, former senior academic engagement librarian, Brown University Library.

[81] Nancy K. Turner, “Surface Effect and Substance; Precious Metals in Illuminated Manuscripts,” in Illuminating Metalwork: Metal, Object, and Image in Medieval Manuscripts, ed. Joseph Salvatore Ackley and Shannon L. Wearing (De Gruyter, 2022), 52–110, at 64–68, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110637526-002.

[82] Yonatan Binyam and Verena Krebs, “Ethiopia” and the World 330–1500 CE, (Cambridge University Press, 2024), 30–31; Aaron Michael Butts, “Coins as a Source for History. The Case of the Aksumite Kingdom,” Sciacca, Ethiopia at the Crossroads, 153–59, at 155–56, Tessema and Ayalew, “Some Factors Affecting the Prosperity of Trade in Ethiopia,” 9–10.

[83] “Precious, rare, and foreign religious objects were habitually used to signal the [Solomonic] rulers’ worldly reach to local elites, subjects, and visitors.” Verena Krebs, “Ethiopia’s Connections with Late Medieval Europe,” in Sciacca, Ethiopia at the Crossroads, 259–65, at 260–61.

[84] Flavonoids are heterocyclic aromatic compounds that are found naturally in most yellow, red, and blue colors of fruits and vegetables. A large group of natural organic colorants, natural dyes, and lake pigments are made from flavonoids.

[85] Scroll with the Lion of Judah, 19th century, Walters, acc. no. W.845; Scrolls, 19th or 20th century, Walters, acc. nos. W.947 and W.954.

[86] Seven healing scrolls at the Musée du quai Branly had an organic yellow pigment that could not be identified with XRF or x-ray diffraction (XRD). Richardin et al., “Les rouleaux protecteurs,” 81. See also Tomaszewski et al.,“Ethiopian Manuscript Maywäyni 041,” 106.

[87] Richardin et al., “Les rouleaux protecteurs,” 81.

[88] Walters, acc. nos. W.835, W.836, and W.850; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, acc. no. 2012.301; and Melikian 389.

[89] Morgan, MS M.828; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, acc. no. 2012.301; Walters, acc. no. 36.9; and Melikian 389.

[90] Morgan, MS M.828; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, acc. no. 2012.301; Walters, acc. nos. W.850, 36.9, and 36.10; Peabody Essex Museum, acc. no. E67892; and Melikian 389.

[91] Maria Bulakh, “Basic Color Terms from Proto-Semitic to Old Ethiopic,” in Anthropology of Color: Interdisciplinary Multilevel Modeling, ed. Robert MacLaury, Galina Paramei, and Don Dedrick (John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2007), 252.

[92] Bulakh, “Basic Color Terms,” 252.

[93] Richardin et al., “Les rouleaux protecteurs,” 82.

[94] This same practice was observed in a group of five fifteenth-century Ethiopian icons from the Walters collection. See French et al., “Technical Research,” 276.

[95] Chernetsov, “Magic Scrolls,” in Uhlig, Encyclopaedia Aethiopica 3, 642–43.

[96] In an effort to both preserve and revive Ethiopian scribal practices, scholars have worked since the late 1950s to record the recipes that have been orally passed down among practitioners of this ancient craft. With the exception of recipes for black writing inks, no traditional recipes for the colored inks and paints historically used to write and decorate Ethiopian manuscripts have survived. See Balicka-Witakowska et al., “Ethiopic Codicology,” 157.