The second half of the nineteenth century saw intense experimentation by French craftspeople working with enamels, and the medium was taken to new creative and technical heights. Displayed at well-attended and widely publicized international exhibitions, enameled objects were discussed and celebrated as part of French patrimony. More generally, the decorative arts gained official status.[1] The career of Fernand Thesmar (French, 1843‒1912) was intertwined with these developments. From 1891 he exhibited to great acclaim at the Salon, and his enamels were purchased for public collections in his native France, as well as Germany, Britain, Russia, Japan, and the United States. Well-placed critics wrote about the artist and his work, including Édouard Garnier (1840‒1903), the curator of the National Porcelain Museum at Sèvres, and Victor Champier (1851‒1929), who headed the campaign to establish a national museum of the decorative arts in Paris and was director of the Revue des arts décoratifs.[2] In 1893 Thesmar was made a Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur for outstanding service to France. In 1912, the year he died, a three-volume history of French goldsmithing by Henri Bouilhet emphatically declared, “He is not only among the first rank of enamellists: he is the first.”[3]

Unidentified artist, The Mérode Cup (cup and cover), ca. 1400, silver, silver gilt, gold, plique-à-jour enamel plaques, H: 3 15/16 × Diam: 6 7/8 in. (17.5 × 10 cm). The Victoria and Albert Museum, London, acc. no. 403:1, 2-1872

Thesmar’s fame rested on his rediscovery of a technique lost for centuries for making objects from transparent enamel.[4] Enamel consists of glass powder heated so that it melts and becomes attached to a support, be that metal, glass, or ceramic. Thesmar sought to do away with the supporting element so the glass was held by only thin strips of metal, allowing light to pass through the resulting form.[5] In the nineteenth century, medieval examples of transparent enamel were known through written descriptions—notably, Francis I of France (1494‒1547) was recorded to have shown an example to the Italian goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini—but only a single example from the period survived: the Mérode Cup (fig. 1), which was purchased by the South Kensington Museum (today the Victoria and Albert Museum) in 1872.[6] Thus, when Thesmar exhibited eleven transparent enamels at the 1891 Salon, they caused a sensation. Three were immediately acquired by the Musée des Arts Decoratifs, and one entered the Musée du Luxembourg (this is now in the Musée d’Orsay) (fig. 2).[7] The excitement Thesmar’s transparent enamels produced can be sensed in an article by Garnier that quickly appeared in the Revue des arts décoratifs. He writes, “We can strongly affirm that we have never seen works of this genre as important and as perfect.”[8] The somewhat awkward attempt Garnier makes to describe transparent enamels further underlines their novelty. He writes, “In Mr. Thesmar’s cups . . . the enamel is not a simple adjunct . . . it is the whole piece itself. The decorative patterns, flowers, lambrequin [decorative edge] trim, base, etc., drawn with thin gold lineaments that hold the enamels, stand out against a background of transparent or opaque enamel of admirable purity, and everything is protected at the upper edge and the base by only a thin golden circle.”[9] In conclusion, he predicts that the cups acquired by the French state “will remain as first and precious testimonies of one of the most admirable examples of an art of which France can rightly be proud.”[10]

Fernand Thesmar (French, 1843‒1912), Tasse (Cup), 1891, enamel, gold, H: 1 15/16 × Diam: 3 2/3 in. (5 × 9.3 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris, acc. no. OA 3288

Thesmar had begun his career designing tapestries, carpets, and other elements of interior decoration for several different companies. In 1872 he began to work for Barbedienne, a well-established Parisian firm of bronze founders.[11] Ferdinand Barbedienne, who ran the bronze foundry between 1859 and his death in 1892, had become interested in the production of enamels in the late 1850s, amassed a collection that could be studied by his employees, and established a laboratory for analysis of and experimentation in the medium.[12] Thesmar designed enamels for the firm, and he headed their enameling studio.[13] According to an 1896 article written by Champier it was during this period that Thesmar threw himself into the study of enamel with “passionate ardor.” [14] Sometime around 1886/7 Thesmar left Barbedienne’s employment and began to work independently in his own workshop. By 1887 he had perfected the technique of transparent enamel.

In surveying thirty-five of Thesmar’s transparent enamels, both in museum collections and appearing at auction, commonalities emerge.[15] Most take the form of small cups, around three-and-a-half inches (or nine centimeters) wide and around two inches (or five centimeters) tall. Thesmar includes his cipher, a symmetrical arrangement of his combined initials, in enamel on the bases of these objects, often along with a date. Some cups have a rounded profile, while others flare slightly at the brim, and a few have straighter sides, but they are otherwise quite uniform. The designs depicted in the enamel are often very similar, although the colors may change or the pattern at the base or rim may vary. Anemones, violets, and stylized flowers, often inspired by Islamic designs, appear on the majority.[16] Departures from the more usual cup form include a “mosque lamp” acquired by the Musée du Luxembourg from the artist in 1892,[17] a large piece made for Tsar Nicolas II of Russia in honor of his visit to Paris in October 1896,[18] and a cup and saucer shaped after dandelion plants from 1902 and 1903, also purchased by the Musée du Luxembourg.[19]

Fernand Thesmar (French, 1843‒1912), Cup, 1887‒1888, transparent enamel, gold, H: 1 3/4 × Diam: 3 11/16 in. (4.4 × 9.3 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, William T. Walters, by commission, ca. 1887, acc. no. 44.572

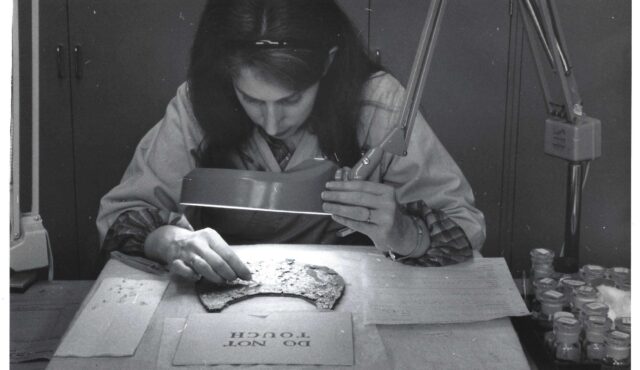

Two of the three transparent enamel cups in the collection of the Walters Art Museum also stand out among Thesmar’s work; although they share the cup form Thesmar frequently employs, they bear names in red as part of their decoration. The lettering on one reads “W. T. Walters” (fig. 3), for William Thompson Walters (1819‒1894), the businessman, collector, and father of Henry Walters (1848‒1931), who bequeathed their collections to Baltimore, founding the Walters Art Museum. The name of the American writer Theodore Child (1846‒1892) appears on the other (fig. 4).[20] Unusually, although Thesmar’s cipher appears on their bases, they are not dated. This article focuses on dating these two cups and concludes that they are among Thesmar’s earliest productions in transparent enamel. An accompanying note by Gregory Bailey, Senior Objects Conservator at the Walters, supports this dating. In addition, and perhaps surprisingly, the cup decorated with Walters’s name was almost immediately shown publicly in Baltimore in 1888, three years before Thesmar exhibited his transparent enamels at the Salon in Paris.

Fernand Thesmar (French, 1843‒1912), Cup, 1887‒1888, transparent enamel, gold, H: 2 3/8 × Diam: 3 7/16 in. (6 × 8.7 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by William T. Walters before 1893 (perhaps 1891?), acc. no. 44.571

Turning first to the cup decorated with letters spelling out “W. T. Walters” (fig. 3), it, like the cup with the name “Theodore Child,” is unusual in that it is inspired by Gothic, rather than Islamic or Asian, art. Each red letter appears within a white trefoil, which is framed within blue circles. These circles and trefoils are further subdivided with extremely fine wires and cells in light and dark green enamel, a technique that is not repeated elsewhere in Thesmar’s work but resembles the handling of the transparent enamel panels in sections of the Mérode Cup. An article from March 1888 titled “A Wonderful Enamel—A New Treasure of the Walters Collection” published in the Baltimore American includes the cup, so it must predate this.[21] The anonymously authored article, which misspells Thesmar’s name as Tismar, recounts that the cup was fired ten times, with more enamel being added each time to fill the gaps in the metal framework, and that the work “occupied eight months,” so presumably it had begun in 1887 at the latest.[22]

The cup decorated with the name “Theodore Child” (fig. 4) is of a slightly different shape, with straighter sides, and stands on an elaborate pierced gold base from which projects three enameled fleur-de-lis or leaves that create feet. This base is unique among Thesmar’s transparent enamels, which are usually formed of simple gold bands. In this example, the red Gothic lettering appears on a translucent pale green ground without further subdivisions. The decorative bands at the rims and base of this cup are almost identical to those on the cup decorated with Walters’s name.[23] Child wrote about art and travel for English and American magazines. An obituary noted that he was “in charge of the foreign office of Harpers’ publications,” and that “his judgement upon art was especially good, and his essays upon paintings and sculptures and etchings . . . were notable both for matter and manner.”[24] An undated museum label in the Walters’ curatorial file identifies this cup as memorializing Child, who died suddenly of cholera while traveling in Iran, which would mean that it must date to after 1892. However, I have found no documentary evidence to support the idea that this object was made to commemorate Child. A possible source for the false idea that the cup was a memorial to Child is its mention in a January 1893 article, again published in the Baltimore American, with the title “Walters’ Art Gallery, The Splendid Collection Growing Larger Year by Year.” The author of the article, again misspelling Thesmar’s name, states, “Interest in the Tismar enamels is at this time heightened by the recent almost tragic death of Theodore Child, whose name appears on one of the cups.”[25]

However, art agent George A. Lucas’s diary, an indispensable source for dating many of William Walters’s acquisitions, mentions a cup in 1891, prior to Child’s death, that could be the one on display in Baltimore by 1893. It is in an entry dated May 25, 1891—the only one in Lucas’s diary that references Thesmar. It reads: “Left Childs [sic] Tesmar [sic] Cup at Miss Cassatt asked for it 2000 fs.”[26] If this entry references the cup which was on display in Baltimore by January 1893, which seems likely, it could not have been commissioned as a memorial to Child. It also raises the possibility that before the cup entered the Walters’ collection, it belonged to Mary Cassatt (1844‒1926), the American-born artist, who lived in France. Like many artists, Cassatt was also a collector; she owned “a modest collection of decorative objects from many periods and styles.”[27] Cassatt knew Lucas, and Henry Walters met her on at least one occasion.[28] Depending on how Lucas’s diary entry is read, it may record the cup’s sale to Cassatt for the high sum of 2,000 francs, or it may record the price Cassatt was asking Lucas to pay for the object.

The idea that this cup, like the cup bearing Walters’s name, dates from the late 1880s finds support in Champier’s 1896 article on Thesmar. Champier writes that in 1888, after leaving Barbedienne’s employ, Thesmar experienced financial difficulties and was in danger of being evicted from his workshop.[29] But, Champier writes, “Fortunately, at this critical hour, a miraculous chance brought Thesmar a friend, the English writer Chield [sic], who had admired his works at the Salon, and from-time-to-time asked him for a few cloisonné enamel bindings. Chield [sic], apprehending the artist’s misadventure, immediately put him in touch with Sichel, the antiquaries. They went immediately to Neuilly [where Thesmar’s workshop was located], understood the advantage they could draw from Thesmar’s ability to execute enamels, and did not hesitate to sign a contract by which they agreed to take all his production during a fixed period.”[30] The writer “Chield” is surely Child, who met Thesmar around 1886 when he published an extensive article on Barbedienne for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine that mentioned the artist.[31] “Sichel” is probably the French art dealer Philippe Sichel (1839‒1889). Sichel and his brothers, Auguste and Otto, specialized in Asian and French art and seem to have catered especially to collectors in the United States.[32] Lucas’s diaries link Child and Sichel, showing that the three men were great friends. In the late 1880s they socialized together, often meeting at Lucas’s apartment for dinner.[33] After Child died, Lucas served as executor of his will. His diaries recall that he had the unhappy tasks of settling Child’s bills, returning property to Harper and Brothers publishers, and clearing his apartment.[34] I would argue that Champier’s account and Lucas’s diaries suggest a date of around 1888 for the commission of Child’s cup. In addition, in his 1896 article on the artist, Champier relates that Thesmar left Paris shortly after his partnership with Sichel, relocating to London for “two of three years” to work for the wealthy collector and connoisseur of enamels Alfred Morrison.[35] He presumably was back in Paris when he first exhibited his transparent enamels in 1891, meaning he left for England in either 1888 or 1889. It can therefore be concluded that the Walters Art Museum’s cups with red Gothic lettering are among the first that Thesmar made using his newly discovered technique of transparent enamel and that they date from the period he was under contract with Sichel.[36]

Thesmar won fulsome praise from his contemporaries.[37] Garnier, the first writer to report on Thesmar’s transparent enamels, concluded that they outdid any examples from the medieval period or the Renaissance.[38] In his report on the Exposition Universelle Internationale in 1900, Bouilhet describes Thesmar as “the complete artist”—a designer, colorist, skilled inventor, and creator.[39] Other critics saw his skills as almost supernatural. Champier ends his 1896 article on the artist with the following words: “What further surprises does this magician have in store for us? . . . He knows how to spread the sparkles of precious stones around him, he draws with carbuncles, he paints with streams of rubies. Will he now tackle the twinkling fire of the stars and reproduce their moving lights?”[40] In Thesmar’s obituary, Gabriel Mourey speculated that “in future museums, in the eyes of those who will come to question the soul of our century, these tiny bowls, these little cups, in transparent gold cloisonné enamels, on which only fairies and angels would be worthy to place their lips, will say that in our utilitarian and violent era, a man could be met with who spent his life pursuing a beautiful dream, that he had the joy of achieving it, and gave his contemporaries the joy of pure enchantment, fragile and lasting beauty.”[41] Such words attest to the significance of Thesmar’s work: in the eyes of many of his contemporaries his transparent enamels confirmed that art and human ingenuity could transcend.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Gregory Bailey, Martin Levy, Earl Martin, and Kristen Nassif for their assistance in bringing this article to completion. All translations in this article are my own.

[1] The Union Centrale des Beaux‐Arts Appliqués à l’Industrie (Central Union of the Fine Arts Applied to Industry), later renamed the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs (Central Union of the Decorative Arts), was given legal recognition in 1864. Beginning with its 1890 spring exhibition (Salon), the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (National Society of the Fine Arts) exhibited decorative art objects as a distinct group alongside paintings and sculpture, and in 1895 the Société des Artistes Français (Society of French Artists) followed suit. This was highly significant, as works shown at the Salon were eligible for purchase by the French state. Such purchases began in 1892. In 1905 the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Museum of Decorative Arts) opened to the public in its permanent home: the Pavillon de Marsan, a wing of the Louvre. This gave the decorative arts presence within this prestigious museum complex. For good overviews of these developments, see Leora Auslander, Taste and Power: Furnishing Modern France (University of California Press, 1996); Debora L. Silverman, Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siècle France: Politics, Psychology, and Style (University of California Press, 1989); and Claire Jones, Sculptors and Design Reform in France, 1848 to 1895: Sculpture and the Decorative Arts (Routledge, 2016). See also Odile Nouvel-Kammerer, “The Collections of the Musée des Arts Decoratifs,” in Matières de rêves: Stuff of Dreams from the Paris Musée des Arts Decoratifs, ed. Penelope Hunter-Stiebel and Odile Nouvel-Kammerer (Portland, OR: Portland Museum of Art, 2002), 15‒19.

[2] Édouard Garnier, “Les coupes de M. Thesmar acquises par le Musée des arts décoratifs,” Revue des arts décoratifs 11 (1891‒1892): 285‒87; Victor Champier, “Fernand Thesmar,” Revue des arts décoratifs 16 (1896): 373‒81. Champier’s long article on Thesmar provides vital information about the artist’s career. For more on Champier, see Victor Champier papers, 1834‒1929, https://www.getty.edu/research/collections/collection/113Y98.

[3] Henri Bouilhet, L’Orfèvrerie française aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles . . . livre troisième, 1860‒1900 (H. Laurens, 1912), 368. A version of this entry on Thesmar had appeared a decade previously in the Rapports du Jury International, vol. 15, pt. 1, (Imprimerie Nationale, 1902), 230. Bouilhet was a vice president, and briefly president, of the Central Union of the Decorative Arts. Given Thesmar’s success it is surprising that little secondary literature exists on the artist. The most useful source in English was published in 1987: a page-long entry by Richard Edgcumbe in a book of highlights from the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection of nineteenth-century European and American art and design (Art and Design in Europe and America, 1800‒1900, ed. Simon Jervis [E.P. Dutton, 1987], 156‒57). See also Alastair Duncan, The Paris Salons, 1895‒1914, vol. 5, Objets d’Art and Metalware (Antique Collectors Club, 1999), 26, for a paragraph on the artist. In 1994 a longer article appeared in L’Objet d’art, which surveys Thesmar’s career. See Régine de Plinval de Guillebon, “Fernand Thesmar émailleur sur cuivre, or et porcelaine,” L’Objet d’art, no. 276, January 1994, 44‒53.

[4] Some jewelers had produced small sections of transparent enamel, though likely using a different technique from that employed by Thesmar. See Gregory Bailey’s note in this volume, “The Transparent Enamel Cups of Fernand Thesmar: Considerations on Technique.”

[5] This process is often termed plique-à-jour, French for “letting in daylight”; however, I have found the phrases émail transparent (transparent enamel) or émail translucide (translucent enamel) are more often used in primary sources. In this article I have used transparent enamel to describe this technique.

[6] In 1862, the cup was shown to great acclaim at the International Exhibition in London. Champier and Garnier both refer to this object in their articles on Thesmar.

[7] Antonin Proust, Le Salon de 1891 (Boussod, Valadon et Cie, 1891), 75. Proust records that Thesmar was a “newcomer to these exhibitions,” showing “eleven transparent cloisonné gold enamel bowls and four brooches.” See Garnier, “Les coupes de M. Thesmar,” 285, and A. Hustin, Le Salon de 1891, Société des Artistes Français et Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (L. Baschet, 1892), 103. Hustin lists two enamel cups as having been purchased; only one is described as specifically being made of “transparent enamel, gold cloisonné.”

[8] Garnier, “Les coupes de M. Thesmar,” 285.

[9] Garnier, “Les coupes de M. Thesmar,” 287.

[10] Garnier, “Les coupes de M. Thesmar,” 288.

[11] For Thesmar’s work prior to entering a contract with Barbedienne, see Champier, “Fernand Thesmar,” 374, 375.

[12] See Florence Rionnet, Les Bronzes Barbedienne: L’œuvre d’une dynastie des fondeurs (1834‒1954) (Arthena, 2016), 83, 84. Barbedienne’s collection was later sold to Potter and Bertha Honoré Palmer of Chicago.

[13] See Champier, “Fernand Thesmar,” 376. Presumably his contract with Barbedienne was like the one the firm signed with the designer Louis-Constant Sévin (French, 1821‒1888). This is reproduced in appendix 1 of Jones, Sculptors and Design Reform in France, 193‒94. A representative example of Thesmar’s work from his time with Barbedienne is a charger inspired by Japanese and Chinese enamels, which was likely purchased by William Walters (Walters Art Museum, acc. no. 44.654).

[14] Champier, “Fernand Thesmar,” 375, 379.

[15] I have been able to find images and details of thirty-four examples of transparent enamels by Thesmar. They suggest that Thesmar always monogrammed these works on the base and typically added a date. The earliest examples with dates on their bases are in the Musée d’Orsay and marked 1891 (these were acquired from the Salon, as described by Garnier). The latest dated examples are from 1908 and appeared at auction in 2016 and 2018.

[16] For example, a cup in the Musée d’Orsay (acc. no. OAO 204), featuring white anemones on a white background, appears to be exactly the same as a cup in the Toledo Museum of Art (acc. no. 2005.43). The same design, with deep red flowers on a white background, can be found in the Walters’ collection (acc. no. 44.573). In 1902 the American journal Brush and Pencil published a black and white photograph of a cup with the same design but with no enamel surrounding the flowers, creating a pierced effect. See “Gleanings from American Art Centers,” Brush and Pencil 11, no. 3 (December 1902): 223‒29, at 228 (cup to the right). The image is captioned “Bowls of Transparent Enamel / By Fernand Thesmar / Paris Salon, 1902.” Similarly, compare the cup in the Victoria and Albert Museum (acc. no. 357-1894), decorated with stylized flowers, with black and white photographs published in Brush and Pencil, and with Thesmar’s obituary in Les Arts. See also E. Harvey Middleton, “The Art Industries of America: VII, Enameling on Metal,” Brush and Pencil 16, no. 3 (September 1905): 66‒74, at 70 (cup to the left; this article also republished the photograph cited above from December 1902, at 69), and Gabriel Mourey, “Fernand Thesmar,” Les Arts, no. 129, 1912, 19‒22, at 19 (cup to the left).

[17] This is now in the Musée d’Orsay (acc. no. OA 3289).

[18] A photograph of this piece accompanied Thesmar’s obituary in Les Arts. For more on the cultural significance of the Tsar’s visit, see Silverman, “Rococo Revival and the Franco-Russian Alliance,” in Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siècle France, 159‒71.

[19] These are now in the Musée d’Orsay (acc. nos. OAO 205 and OAO 206).

[20] Another monogrammed cup, decorated with a letter S threaded through a D and dated on the base 1909, appeared at auction in 2022 (Thierry de Maigret, Paris, April 1, 2022, lot 413). I would like to thank Earl Martin for drawing my attention to this. The third cup by Thesmar in the Walters collection is dated 1903, after William Walters’s death, and so we can assume that it was purchased by Henry Walters, who continued to collect works by artists his father favored, while also expanding the scope of his father’s collection. This cup is decorated with anemones, a pattern seen in other examples, and, while rare, is not unique.

[21] “A Wonderful Enamel,” Baltimore American, March 15, 1888, 8.

[22] The Baltimore American refers the reader to an article by Child published “about a year since” for an account of the cup. Likely, this reference is to a long article by Child on the Barbedienne firm that appeared in 1886 in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, but although this mentions Thesmar, it does not discuss transparent enamel. See Theodore Child, “Ferdinand Barbedienne. Artistic Bronze,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 73, no. 436, September 1886, 489–504.

[23] The same decoration at the rim and base can be seen in a cup illustrated in Thesmar’s obituary. See Mourey, “Fernand Thesmar,” 20 (cup to the right).

[24] See “Theodore Child,” San Francisco Call, November 18, 1892, 8.

[25] “Walters’ Art Gallery, The Splendid Collection Growing Larger Year by Year,” Baltimore American, January 29, 1893, 3. This article also mentions that the cups could now be seen to “fresh advantage” as “they no longer rest upon small velvet pedestals, but hang by silver chains from the top of the cabinet, and present almost the appearance of fairy lamps.”

[26] Lilian M. C. Randall, The Diary of George A. Lucas: An American Art Agent in Paris, 1857‒1909 (Princeton University Press, 1979), 2:729.

[27] Nancy Mowll Mathews, Mary Cassatt: A Life (Yale University Press, 1998), 264.

[28] In April 1903 Henry Walters visited Mary Cassatt’s apartment with Lucas and agreed to purchase two paintings from her: Claude Monet’s painting of his wife, Camille, known as Springtime, and Edgar Degas’s portrait of his cousin, Estelle Musson Balfour (acc. nos. 37.11 and 37.179). For this visit, see Stanley Mazaroff, A Paris Life, A Baltimore Treasure: The Remarkable Lives of George A. Lucas and His Art Collection (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018), 141, and Randall, The Diary of George A. Lucas, 2:913.

[29] Champier, “Fernand Thesmar,” 378‒79.

[30] Champier, “Fernand Thesmar,” 379.

[31] Child wrote, “from the ovens of the enamel department artists like Thesmar were succeeding in introducing into our habitations some of the harmonies of colors familiar to Eastern people” (“Ferdinand Barbedienne. Artistic Bronze,” 492). The article includes a wood engraving of the Cloisonné Enamel Shop (504). It is tempting to identify the man in a suit seated at a desk just to the right of center as Thesmar. Photographs show that Thesmar had a moustache and receding hairline, like this figure. In his 1891 and 1892 articles on the Salon of the Champ de Mars, Child mentions Thesmar in both: in the former with great praise, but in the latter questioning his choice of colors. See Theodore Child, “The Salon of the Champ de Mars,” Art Amateur, July 1891, 25, and Theodore Child, “The Salon of the Champ de Mars,” Art Amateur, July 1892, 27.

[32] See Max Put, Plunder and Pleasure: Japanese Art in the West, 1860–1930 (Hotei Publishing, 2000), especially “Biographical sketches of the authors: Philippe Sichel,” 33‒38.

[33] See, for example, Randall, The Diary of George A. Lucas, entry for April 25, 1888: “To dinner with Marks at Restaurant de Londres with Child & P. Sichel,” 2:668; entry for November 14, 1888: “Child & P. Sichel to dinner,” 2:679; entry for November 9, 1890: “Child, Dannat and Philippe Sichel to dinner,” 2:719. Significantly both men met Lucas’s mistress, Maud, revealing the degree of trust and intimacy between them.

[34] See Randall, The Diary of George A. Lucas, entry for July 4, 1892: “Visit in evening from Dr Touze & Child who gave me his will before leaving for Persia,” 2:749; entry for May 23, 1893: “At Cachards [sic] & with him to have Drexel turn over Bonds T C [Child] estate to Jobson—retained a part for my safety in setting estate,” 2:769; entry for May 27, 1893: “At 99 Ave Villiers & loaded 2 wagons (1 horse) the remnants of Childs [sic] affairs,” 2:769.

[35] Champier notes that Sichel had sold a cup to Morrison, prompting the Englishman’s interest. See Champier, “Fernand Thesmar,” 380. For more on Morrison, see Caroline Dakers, A Genius for Money: Business, Art and the Morrisons (Yale University Press, 2011), especially “Alfred Morrison, 1821‒1897: ‘Victorian Maecenas,’” 225‒47, and Olivier Hurstel and Martin Levy, “Charles Lepec and the Patronage of Alfred Morrison,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 50 (2015): 194‒223.

[36] This attests to the swiftness with which collectors in the United States were able to respond to the latest developments in the Parisian art world by working with local agents, or through the efforts of dealers such as Goupil et Cie, who were able to quickly bring the latest success stories from Paris to America.

[37] His work also drew criticism on occasion. For example, a curator at the South Kensington Museum (renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1899) wrote in consideration of a transparent enamel cup proposed for purchase, “All the works of this kind I have seen by Monsieur Thesmar . . . have appeared to me objectionable and unsuitable to our museum on account of bad taste in design generally and especially of the crude contrasts of colour in them” (C. P. Clarke, quoted by Edgcumbe in Jervis, Art and Design in Europe and America, 157). In a review of the enamels on display in 1902, Léonard Penicaud asked, “why doesn’t he vary the shape of his little cups, which are always a little too similar. I regret it and, from what I have heard around me, I am not alone in regretting it” (Léonard Penicaud, “L’émail aux salons de 1902,” Revue de la bijouterie, joaillerie, orfèvrerie September 1, 1902, 163‒78, at 165).

[38] See Garnier, “Les coupes de M. Thesmar.”

[39] Bouilhet, L’Orfèvrerie française, 368.

[40] Champier, “Fernand Thesmar,” 381.

[41] Mourey, “Fernand Thesmar,” 22.