The Walters Art Museum holds a number of Renaissance and early modern mortars (vessels for pulverizing and compounding medicines),[1] perhaps the most significant of which is a large sculptural example cast by Ambrogio Lucenti (Italian, 1586‒1656) in bell metal, a form of bronze (fig. 1). Lucenti was a famed Roman foundryman who produced a number of works for the Vatican, including portions of the baldachin for the altar of Saint Peter’s Basilica after designs by Gianlorenzo Bernini (Italian, 1598‒1680).[2] This large mortar was purchased by Henry Walters (1848‒1931) in 1902 from the Italian collector Marcello Massarenti (1817‒1905), together with a large collection of art and artifacts housed in the palazzo Accoramboni in Rome.

Ambrogio Lucenti (Italian, 1586‒1656), Mortar with Hygeia/Salus, 1654, cast bronze with natural patina, H: 13 3/4 × Diam: 16 9/16 in. (35 × 42 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters with the Massarenti Collection, 1902, acc. no. 54.656

The mortar is decorated in low relief on the exterior, while the interior has smooth walls and a rounded, concave bottom. There are some superficial marks and wear around the rim, yet the interior does not show any signs of use (i.e., marks from a pestle, such as dents or gouges). The heavy flaring lip of the mortar is decorated with two bands of hemispherical beads; between them a Latin inscription extends around the circumference, beginning and ending with the sign of a cross (“+”): “ASPICE QUID STABILIS POSSIT CONCORDIA RERUM QUE SOCIATA IVVANAT DISSOCIATA NOCEAT 1654,” (roughly, “Behold what you establish; the harmony of things may be possible that it may assist the things united [and] harm the things separated”).[3] Below the lip on the body of the mortar are two further bands of hemispherical beads, interrupted by two figures of doves on opposite sides, whose wings rise to support the lip. One of the doves is wrapped in a cord, from which is suspended a portrait medallion with the inscription “INNOCENTI X PONT MAX,” identifying the portrait as Pope Innocent X (Giovanni Battista Pamphilj, 1574‒1655, pope from 1644).[4]

Around the tapering cylindrical body of the mortar are a series of swags of indistinct fruit enclosing fleurs-de-lis. Between the doves on one side is a heraldic device (coat of arms) combining the arms of the Pamphilj and Aldobrandini families surmounted by a crown and flanked by tassels. Opposite this device is a representation of a reclining female figure in classical garb offering a patera (small bowl) to a snake entwined around an altar. These attributes have led to the figure’s identification as the Greek goddess Hygeia, associated with good health and the prevention of sickness; however, the figure may be better identified as Salus, the Roman goddess of health, welfare, and prosperity, whose ancient cult was associated with the well-being of the Roman state.[5] Below this register runs another band of the same hemispherical beads, with a row of curved, overlapping acanthus leaves below. The foot is decorated with four simple incised bands spaced at irregular intervals and completed with the inscription “AMBROSIO LVCENTI ROM- FCA OPVS.”[6]

The inclusion of the arms of both the Pamphilj and Aldobrandini families, together with the doves (emblems of the Pamphilj) and the portrait of Innocent X, led former Walters curator Marvin Chauncey Ross to venture that the mortar may have been commissioned by the Pamphilj—or perhaps by Pope Innocent X himself—to commemorate the 1647 marriage of Olimpia Aldobrandini, Princess of Rossano, to Prince Camilo Pamphilj, nephew of Pope Innocent X.[7] This interpretation is supported by the inscription around the rim, which Ross did not consider but may be read as a reference to the function of a mortar (that is, to compound separate ingredients into health-giving medicines, a reading enhanced by the depiction of the goddess Salus), as well as an allegory for dynastic marriage (the harmonious union of two separate families, represented by the combined arms of the Pamphilj and Aldobrandini).[8] Taken together, the inscription and the decorative scheme transform what would otherwise be a utilitarian object into a metaphorical representation of healthy marriage, probably meant to be regarded more as sculpture than as a household object. Indeed, similarly large and decorative mortars are thought to have been largely ornamental, as they almost never show signs of use, including another example by Ambrogio Lucenti, now at the Victoria and Albert Museum (fig. 2).[9]

Ambrogio Lucenti (Italian, 1586‒1656), Mortar with lion-headed handles and lizard, 1642, cast bell metal, H: 33 cm × Diam: 43 cm (max.). Victoria & Albert Museum, Bought with funds from the Bequest of Captain H.B Murray, acc. no. A.2-1974

Ross (in 1943) speculated that the Walters mortar could have been intended as decoration for the Villa Bel Respiro (now known as the Villa Doria-Pamphilj, near Porta San Pancrazio, Rome), which was built 1645‒47. The villa’s gardens and interior decoration were completed in 1653. This is plausible, as the mortar is dated to the following year and the villa was built for Camillo Pamphilj and Olimpia Aldobrandini, whose marriage the mortar seems to commemorate. Furthermore, Lucenti cast several bronzes from models by Alessandro Algardi (Italian, 1598‒1654),[10] and it is believed that Algardi was one of the principal artists responsible for the design of the Villa Bel Respiro, suggesting a possible artistic link. However, no firm evidence has tied the mortar to the Villa Bel Respiro/Doria-Pamphilj. It is unknown how it entered the collection of Marcello Massarenti, though the upheavals of the Italian unification in the middle of the nineteenth century saw many items of aristocratic provenance change hands.

The Victoria and Albert example is similar to the Walters mortar in size and form,[11] but it has a rather different decorative scheme, consisting of two handles supporting grotesque masks on opposite sides, an unidentified coat of arms,[12] and a lizard and leaf, possibly cast from life. It also includes a portrait of Pope Urban VIII, reproduced from a medallion by Gaspare Mola (Italian, 1567 or 1571‒1640), a fact that has been interpreted as evidence that the mortar belonged to the papal pharmacy.[13]

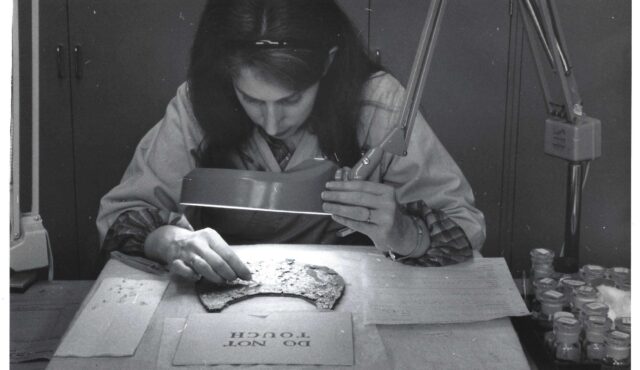

Note the wings and tails of the damaged bird handles in the second and fourth views.

Ambrogio Lucenti (Italian, 1586‒1656), Mortar, 1653, cast bronze, H: 49 × Diam: 53 cm. Ospedale di Santo Spirito in Sassia, Rome, recorded as no. 1200217929 in the Italian Catalogo Generale dei Beni Culturali

Another, much more closely related example by Lucenti, dated 1653, remains in the Ospedale di Santo Spirito in Sassia, Rome (fig. 3).[14] The S. Spirito example (signed “AMBROSIO LVCENTI ROMANO CA.[mera] AP.[ostolica] OPVS”) is slightly larger than the Walters mortar,[15] but of the same form, with exterior decoration divided into the same registers with the same, or very similar, hemispherical beads. The inscription around the rim (“SPIRITUS SANCTE DEUS ANNO DOMINO NOST IESU CH MDCLIII +”)[16] and the primary decoration in relief on the body—a putto bearing the forked cross that appears on the official seal of the Ospedale di S. Spirito—indicate the mortar was purpose-made for that institution. An oval portrait medallion above a short banner and a wolf or dog appears opposite the putto and cross, though the figure is not identified in available records or identifiable from available photographs.[17] The presence of such a mortar in what was once the largest hospital in Rome is not surprising,[18] though the extremely large size and highly decorated surface seem unusual. By the seventeenth century, mortars were understood as symbols of pharmacy in general and often employed as emblems of specific pharmacies.[19] Large decorated mortars showing the name of a pharmacy or patron were also created for display.[20]

In the lower registers, the S. Spirito mortar is encircled by swaying acanthus leaves very similar to those on the Walters example—possibly taken from the same mold—and also features similar fleurs-de-lis. Intriguingly, in photographs, it appears that the S. Spirito mortar once had high relief birds in the same position and configuration as those on the Walters example, though they have been damaged and partly lost, with only the wings and tails now remaining.[21] If indeed the birds were doves, it is possible that this was another Pamphilj commission, an association that could potentially be bolstered or disproven by the identification of the person represented in the portrait medallion. The close parallels in form and decoration between the Walters and S. Spirito mortars, the possible reuse of molds and motifs, and the fact that they were cast only a year apart could argue for a close association between the two, making the question of patronage especially interesting.

It should be noted that while all three mortars are signed with some version of Ambrogio Lucenti’s name, an abbreviation referencing the Vatican foundries,[22] and the word “OPVS” in recognition of Lucenti’s role as founder, it is unclear to what extent Lucenti may have been responsible for the designs or models. The Victoria and Albert example has an inscription around the rim (“SIMANDIVS DE TOTIS VRBEVANTANVS CIVIS ROMANVS ANNO D M D CXLII FECIT +”)[23] that makes clear that one Simandio de Toti “made” the mortar, though this is almost certainly a recognition of the patron rather than the modeler. Lucenti also cast sculpture after models by Bernini and Algardi, as mentioned previously, as well as bells[24] and cannons.[25] Whether or not Lucenti created his own models or designs, he seems to have been primarily a foundryman specializing in preparing molds and casting metal, as none of his surviving works show any signs of finishing or chasing (sharpening details or adding texture with a chisel) after casting.[26]

The Walters mortar is made of cast bell metal (an alloy of copper and tin, with ~20% or more tin by weight), known for its resonant quality. Initial results of semi-quantitative x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) performed on several spots on the surface confirm the presence of copper and tin and further indicate that the alloy contains a significant portion of lead as well.[27] The resonance of the mortar when gently struck and the considerable weight (perhaps as much as 250 lbs) support these conclusions.[28]

The casting of bells and mortars are closely related processes and, in the seventeenth century, customarily employed similar alloys.[29] Both are typically cast by the direct lost-wax casting process,[30] though the use of strickles (contour profiles for shaping the inner and outer surfaces of the forms) and press molds for decorative motifs allowed for some degree of reproducibility. The entire forms could be modeled in wax, or the basic form could be modeled in clay, with surface decoration added in wax.[31]

Close examination of the surfaces of the Walters mortar suggests that the form was modeled in clay and the relief decoration added in wax; join edges remain crisp and slightly separated in some areas, suggesting the two materials did not fuse together perfectly. It appears that molds were used for some of the relief decoration, including the beads, the fruit swags, fleurs-de-lis, the acanthus leaves, and the letters and numbers (with the exception of the number “5” and the tails of the “Qs”, which were added freehand).[32] The coats of arms and figure of Salus appear to have been modeled freehand. While there is considerable freehand work on the two doves, it is possible that they were formed partly with molds and finished in the wax by hand. The foot appears to have been made separately in wax or clay and added to the body. Whichever material was used, it did not completely join: a partial separation is present around approximately half of the circumference of the mortar at the juncture of the foot and body.

The relatively simple forms and solid casting of bells and mortars does not necessitate the use of core pins, elaborate gates and channels, or even multipart molds, thus eliminating flashing lines (metal seepage between sections of a mold), meaning there is typically little or no need for finishing after casting, apart from removing the sprue (casting cup). In typical fashion, there are no signs of cold finishing or chasing on the Walters mortar. One very slight flashing line is present across the proper left ankle of the figure of Salus, though this is likely due to a small crack in the outer mold, or cope, and not to any joins in the mold.[33]

By the middle of the seventeenth century, the Pontifical Foundry of the Lucenti, located adjacent to the Vatican in the Passetto di Borgo Pio, had already been in operation for a century, as evidenced by the large bell cast by Ambrogio’s forebear Camillo Lucenti, dated 1550, now in the convent of the Capuchin Fathers in the church of Misericordia in Via Veneto, Rome.[34] Ambrogio Lucenti’s skill in casting and his prodigious output were thus informed by generations of family experience. The descendants of Ambrogio and his son Girolamo continued the business of bronze casting for more than four hundred years, eventually specializing in the production of bells. The last bell was cast in the same workshop in Borgo Pio by a different Camillo Lucenti and his son Francesco in 1993. At that time, Francesco estimated that 80 percent of the bells in Rome had been produced by the Lucenti workshop in its half millennium in operation, with many others produced for locations as far abroad as Ecuador and Ethiopia.[35] The Walters mortar is a sophisticated and well-preserved example of bronze casting for an elite seventeenth-century Roman clientele by one of the most notable founders of the Lucenti family. It is hoped that further comparison with the related example in the Ospedale di Santo Spirito may shed additional light on the patronage and manufacture of this object.

[1] The collection includes nine copper alloy mortars from Italy and Spain dating from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries: acc. nos. 54.205, 54.211, 54.212, 54.221, 54.360, 54.372, 54.373, 54.655, and the subject of this note, 54.656, as well as a number of associated pestles. All of these mortars were purchased by Henry Walters; six from Don Marcello Massarenti in 1902 (acc. nos. 54.211, 54.221, 54,372, 54.373, 54.655, 54.656) and three from Giuseppe Piccoli in 1911 (acc. nos. 54.205, 54.212, 54.360). Additionally, the collection includes three ivory mortars and pestles purchased by Henry Walters in the late nineteenth century: a remarkable seventeenth-century Javanese elephant ivory mortar and pestle, acc. no. 71.1212; a nineteenth-century elephant ivory mortar and pestle, possibly German, acc. no. 71.380; and a nineteenth-century Russian mammoth ivory mortar and pestle, acc. no. 71.380.

[2] This object is one of the subjects of a technical study of Bernini’s bronzes by Evonne Levy, Lisa Ellis, Jane Bassett, Aaron Shugar, Chandra Reedy, David Bourgarit, Mark Daley, Enrico Fontolan, and Brandon Rizzuto. A publication of findings is forthcoming. I wish to thank Evonne Levy, Lisa Ellis, Jane Bassett, and Brandon Rizzuto particularly, as their interest in this mortar was the genesis of this short note, as well as Joaneath Spicer, Curator Emerita of Renaissance and Baroque Art, for her comments on an early draft. For a discussion of Lucenti’s career and work on the Saint Peter’s baldacchino, see Philippe Malgouyres, “Colonnes et Canons. Décors, Usages et Symboles,” in Architectures de Guerre et de Paix, ed. Olga Medvedkova and Émilie d’Orgeix (Mardaga, 2021), 167‒94.

[3] This translation is courtesy of Lisa Anderson-Zhu, Curator of Ancient Mediterranean Art.

[4] Edouard van Esbroeck, Catalogue du Musée de Peinture, Sculpture, et Archéologie au Palais Accoramboni (Rome, 1897), 2:69‒70, no. 302; Marvin Chauncey Ross, “A Bronze Mortar by Ambrogio Lucenti,” Art in America 31, no. 1 (1943).

[5] I am indebted to Lisa Anderson-Zhu for this astute observation. Salus was known in later eras not only through statuary but through widely disseminated Roman coinage, medals, and engraved gems.

[6] The abbreviation FCA references the fusorem camera apostolica; the inscription may thus be read “Ambrosio Lucenti, Citizen of Rome, Work of the Papal Foundry.”

[7] Ross, “A Bronze Mortar by Ambrogio Lucenti.” Ross served as curator of Medieval and later decorative arts at the Walters from 1934 to 1952. During the Second World War he also served as a captain in the US Marine Corps and from 1944 on as a member of the Monuments, Fine Art, and Archives section of the US Army, one of the “Monuments Men and Women” who worked to recover and preserve looted art treasures throughout Europe.

[8] The Latin inscription is somewhat garbled, making a clear reading difficult; however, the reference to a harmonious union of separate parts is unmistakable, and could well have had an added layer of alchemical meaning to an educated seventeenth-century observer. It is also worth considering that the inclusion of Salus, protector of the Roman state, may have been a claim to authority on the part of the Pamphilj, who had acquired great wealth and power by the time of the papacy of Innocent X but could not claim a long aristocratic history in Rome, having relocated there from Gubbio in the late fifteenth century.

[9] Acc. no. A.2-1974. The mortar is signed on the foot “AMBROSII LVCENTIS ROMANI F.C.A. OPVS” and dated 1642. For a discussion of the mortar, and ornamental mortars in general, see Peta Motture, Catalogue of Italian Bronzes in the Victoria and Albert Museum: Bells & Mortars and Related Utensils (Victoria & Albert Museum, 2001), 91‒93.

[10] For example, Lucenti cast the monument to Pope Innocent X in the Ospedale di Trinitá dei Pellegrini, Rome, after designs by Algardi, which are now in the British Royal Collection Trust, inv. no. RCIN901584. It is worth noting that Lucenti’s son Girolamo was also a pupil of Algardi’s.

[11] The V&A mortar is 33 × 43 cm while the Walters example is 35 × 42 cm.

[12] A lion rampant and a bend, with a helm and cresting (Motture, Catalogue of Italian Bronzes in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 92).

[13] V&A records for A.2-1974; see also Motture, Catalogue of Italian Bronzes in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 91‒93.

[14] Italian National Catalogue # 1200217929.

[15] It is 49 × 53 cm.

[16] “Holy Spirit of God the year of our Lord Jesus Christ 1653”

[17] See record no. 1200217929 of the Italian Catalogo Generale dei Beni Culturali, mortaio, opera isolata di Lucenti Ambrogio (attribuito) (sec XVII) (beniculturali.it).

[18] At least seven other large mortars from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries remain in the collection of the Ospedale S. Spirito. See records for this site in the Italian Catalogo Generale dei Beni Culturali.

[19] Motture, Catalogue of Italian Bronzes in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 38.

[20] Motture, Catalogue of Italian Bronzes in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 43. This is described by Philibert Guibert in his 1623 treatise Le Medecin Charitable.

[21] There are also curiously truncated forms below the fragmentary tails of the birds, resembling the terminals of the handles on the V&A example.

[22] As noted above, the “FCA” abbreviation on the Walters and Victoria & Albert examples stands for the fusorem camera apostolica; the “CA. AP.” abbreviation on the S. Spirito example stands for the same.

[23] “Simandio de Toti of Orvieto, citizen of Rome, made 1642”

[24] For example, those in the baptistery of San Giovanni in Laterano and the Vatican bell known popularly as “la chiacchierina.”

[25] Malgouyres, “Colonnes et Canons. Décors, Usages et Symboles,” 173.

[26] Motture, Catalogue of Italian Bronzes in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 93. It is worth noting that a monument to Innocent X cast by Lucenti was in fact finished and chased after casting by Paolo Carnieri; however, the creation of the monument was a collaborative effort by Algardi, Lucenti, Carnieri, and the marble carver Daniele Guidotti. In Italy in the seventeenth century, the activities of artisans remained subject to strict trade guild regulations, meaning complex artworks were most frequently the product of more than one set of hands (Motture, 33). See note 10 above for more on this artwork.

[27] Analysis was performed on December 8, 2022, by Brandon Rizzuto of the Bernini’s Bronzes working group, using a Bruker Tracer V XRF spectrometer. A small sample of the metal alloy was also drilled from the underside of the base for inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis to be performed by David Bourgarit at the Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France (C2RMF). Results of both analyses are forthcoming.

[28] Semi-quantitative XRF of the V&A example (using a Spectrace 6000 unit) identified an alloy composition of approximately 71‒75% copper, 19.5‒22% tin, 3‒4% zinc, 1.5‒2% lead, and small amounts of iron, nickel, and manganese.

[29] Motture, Catalogue of Italian Bronzes in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 18‒33.

[30] In the direct lost-wax casting process a unique model is created in wax and destroyed during the casting process. Indirect lost-wax casting can be used to create multiples of the same object by preparing wax casts from a permanent model.

[31] See Motture, Catalogue of Italian Bronzes in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 24‒33 for a helpful overview of the historical materials and processes described by Theophilus and Biringuccio.

[32] The repeating leaves appear to have been applied in the same left-to-right order as the inscription on the rim; the size and spacing of the leaves are consistent, save for a slightly stretched leaf adjacent to a partial leaf located immediately below the “+” marking the beginning and end of the inscription.

[33] The mortar has an overall dark, nearly black patina that appears to be formed by two distinct layers. A thin, compact dark layer is present on the surface of the copper alloy and may be a chemical or heat-applied patination original to manufacture—some bells and mortars in the V&A collections are believed to have been patinated by brushing oils onto the surface and then heating (Motture, Catalogue of Italian Bronzes in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 30). Over this, another, thicker layer of tinted wax or dried oil is present, which may be a later application.

[34] “Campanaro addio, oggi il din-don è registrato.” Il Giornale d’Italia (Rome), August 5,2008, https://www.ilgiornale.it/news/campanaro-addio-oggi-din-don-registrato.html.

[35] “La famiglia che fa campane dal cinquecento.” La Repubblica (Rome), June 9, 1997, https://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/1997/06/09/la-famiglia-che-fa-campane-dal-cinquecento.html.