The Wall Lights before treatment (October 2019). Images by Austin Anderson

Attributed to Pierre-François Feuchère (French, 1737–1823), Wall Lights, ca. 1787, gilt bronze, 24 1/4 × 12 × 6 1/4 in. (61.6 × 30.48 × 15.88 cm), 24 1/4 × 12 1/2 × 6 3/4 in. (61.6 × 31.75 × 17.15 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, before 1931, acc. nos. 54.2271 and 54.2272

Resplendent with ornate detail and a gilded finish, the Walters Art Museum’s pair of eighteenth-century ormolu (gilt bronze) wall lights (acc. nos. 54.2271 and 54.2272) epitomize the rich qualities of French Neoclassicism (fig. 1). Originating as opulent displays of wealth and fashion, they are as splendid now as they were when first created. Collectors in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including William and Henry Walters, were understandably enamored with these objects. Similar wall lights are found in European decorative arts collections across the globe, including those of the J. Paul Getty Museum,[1] the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[2] and the Musée du Louvre.[3] While the date of their acquisition by William or, more likely, Henry Walters is not known, they do reflect the taste for fine eighteenth-century decorative arts that the father and son seem to have shared. After spending close to forty years in museum storage, the wall lights were brought to the Walters Art Museum’s Department of Conservation, Collections, and Technical Research in 2019. In an initial condition assessment, it was observed that key visual elements of the wall lights were missing. These losses prompted the technical analysis and treatment of the wall lights in order to restore their visual integrity.

Both wall lights are composed of a central fluted torch sprouting from a base of acanthus leaves and surmounted with clouds, lovebirds, and foliage. Two arms adorned with acanthus leaves scroll out and are capped with foliate bobeches, or drip pans. Each bobeche has six bunches of grapes hanging from the bottom and an openwork candle socket of vines and grapes mounted above. At the point where the arms return to touch the main torch, they are encircled by a small wreath of foliage and beads, and connecting the innermost point of each arm’s scroll is a vegetal swag with fruit. Around this same area, two bands of undulating ribbon flare out in loops from the central torch and create a bow, which curls down, each end of the ribbon terminating in a tassel.

The original attribution of these wall lights to Pierre Gouthière (French, 1732‒1813/14),[4] who was celebrated as the most famous Parisian bronze chaser and gilder in the late eighteenth century, is now considered inaccurate.[5] The wall lights were actually created in the workshop founded by Pierre-François Feuchère that included various family members, most significantly his son, Lucien-François. The Feuchère workshop first produced a pair of this wall light model in 1787 for the bedroom of Marc-Antoine Thierry de Ville d’Avray, the Intendant du Garde-meuble de la Couronne (Steward of the French Royal Furniture Repository) in what is today known as the Hôtel de la Marine in Paris.[6] The fate of this first set is currently unknown; however, pairs matching their description include those at the Walters and another pair now in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.[7] The same workshop continued to produce subsequent editions of this wall light model into the nineteenth century. Feuchère also created a similar model with the addition of a third central arm adorned with a cherub. In 1788, two pairs of this three-armed model were produced for Marie Antoinette’s dressing room at Château de Saint-Cloud, as well as another pair, with a slight variation, that was produced for Louis XVI’s inner cabinet at the same palace.[8] These Saint-Cloud versions are now held by the Musée du Louvre[9] and Elysée Palace[10] in Paris. Another set of similar three-armed wall lights is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City[11] and exemplifies the variations produced into the nineteenth century (fig. 2).

Top: Attributed to Pierre-François Feuchère (French, 1737–1823) or Jean-Pierre Feuchère (French, 1807–1852, Pair of Wall Lights, about 1787–1788, gilt bronze, 24 1/4 × 12 9/16 × 7 1/4 in. (61.6 × 31.9 × 18.4 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, acc. no. 78.DF.90

Bottom left: After F. L. Feuchère père (French, d. 1828), Three-Light Wall Bracket, late 18th or early 19th century, gilt bronze, 27 1/4 × 15 1/4 × 9 1/4 in. (69.2 × 38.7 × 23.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acc. no. 1977.1.6-9

Bottom right: Anonymous, Bras à trois lumières, Paris, 1788, gilt bronze, 28 1/3 × 15 3/4 × 9 1/4 in. (72 × 40 × 23.5 cm). Musée du Louvre, Paris, OA 6524 1

The Walters’ wall lights were each manufactured and assembled from at least thirty-five individual decorative parts. To cast the parts, a fondeur (caster) used models to create molds in fine sand, into which molten copper alloy was poured. Then a repareur (recutter) cleaned up the parts, and a ciseleur (chaser) tooled their surfaces to create matte areas and burnished them to create shiny areas. The contrast between shiny and matte surfaces was intentionally used to give the finished object visual dimension. A doreur (gilder) then gilded the parts using the ormolu technique. Ormolu, from the French or moulu (powdered gold), is a process whereby gold powder is amalgamated with mercury and brushed on the surface of the copper alloy. The parts were then heated to drive off the mercury as vapor, resulting in a fine and porous layer of gilding on the surface of the copper alloy. Surfaces that were intended to be shiny were again burnished before the parts were considered completed. Once all of the parts were prepared, they were assembled using screws and rods to create the finished object (fig. 3).[12]

Assembly of the Walters’ Wall Lights (54.2271 and 54.2272) from 35 component parts. GIF by Austin Anderson

In September 2019, after spending nearly forty years in storage, the pair of wall lights was brought to the conservation lab with a number of condition issues. Most visually apparent, several ormolu parts were missing from both lights (fig. 4). The most significant areas of loss were to the arms of object 54.2271, which was missing its entire proper right bobeche and nearby elements including grapes and the underlying wreath. Due to the ornate forms of the wall lights, these losses were especially distracting and gave the composition an incomplete appearance.

Condition diagram, indicating lost elements in red. Left: 54.2271; right: 54.2272. Images and annotations by Austin Anderson

In addition, the gilded surfaces of the objects were disfigured by the presence of copper corrosion products. As a consequence of the thin and porous gilding layer of the ormolu surface, the underlying copper-alloy substrate is relatively exposed to environmental humidity and pollutants and is therefore particularly susceptible to corrosion.[13] Copper corrosion products are often prone to penetrate the gilding from the underlying substrate and manifest externally. Two visually and behaviorally distinct types of corrosion formed on the surface of the wall lights: a thin and pervasive layer of dark powdery corrosion (fig. 5, left) and localized, thick plaques of corrosion (fig. 5, right), likely consisting of copper oxides and sulfides.[14] The thin layer of corrosion overall acted to obscure textural detail, resulting in a general flattening of the surface, which masked precisely modeled details. The thicker plaques of corrosion were even more visually distracting, drawing attention to areas of concentrated discoloration.

Details of corrosion on 54.2272. Diffuse corrosion overall on the foliate scrolling arm may be copper oxides (left) and thick corrosion plaques on the ribbon element may be copper sulfides (right). Images by Jen Mikes

After discussing these issues with the curatorial team, conservators set out to restore the wall lights closer to their intended appearance, as they were unlikely to be exhibited in their existing conditions. Conservators designed a treatment plan, with insight and approval from the curatorial team, and then performed tests to determine the most appropriate materials and solvents to use in the treatment. Following a two-step protocol, conservators were able to locally reduce the disfiguring copper corrosion products. Thinner areas of corrosion were reduced using a pH-buffered gel system containing a chelator, cosolvent, and surfactant.[15] Each element of this cleaning solution worked in tandem to yield the desired results. A chelator acted to bond and sequester the metallic corrosion ions. A cosolvent was added to supplement the effect of the main solvent, facilitating the dissolution of corrosion products. A surfactant was included to produce a stable emulsion between the immiscible solvent and cosolvent. A precisely chosen buffer kept the solution in the optimal pH range to allow maximum effectiveness of the cleaning solution, while causing minimal effect to the original ormolu surface. Finally, a gelling agent, or thickener, was added to improve control on application and increase its dwell time on the surface.

While the customized cleaning solution above was highly effective at gently removing the overall thin layer of corrosion, the thicker plaques were generally unaffected. For these areas, conservators chose a slightly more intense but reliable method, which had been successful in previous conservation treatments at the Walters Art Museum. A dilute formic acid gel easily reduced the thick corrosion plaques, revealing the gilded ormolu surface below. All cleaning solutions were cleared from the surface using deionized water and then ethanol. Because the presence of minor corrosion is consistent with the historical context of ormolu objects such as this pair of wall lights, only the most visually distracting areas of corrosion were reduced. The goal of this cleaning campaign was to create a more uniform surface appearance, rather than attempting to remove corrosion altogether.

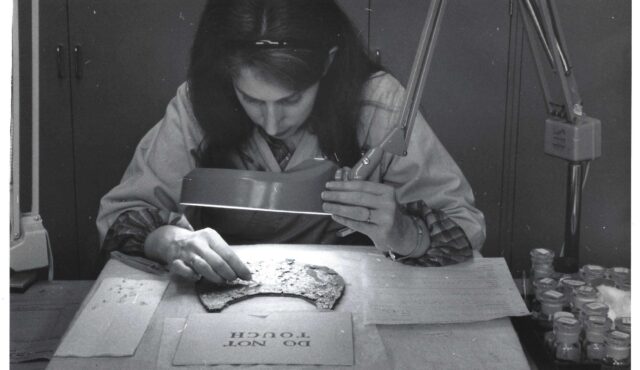

Two-part silicone mold taken from an extant bunch of grapes. Image by Austin Anderson

Following cleaning, the curatorial and conservation teams determined that it was important to replace missing component parts of the wall lights to restore their balanced compositions. To minimize intervention, only the most distracting losses were replaced, including the bobeche, wreath, and grape elements on 54.2271, and the missing bunch of grapes on 54.2272. All replacement parts were cast in a clear, conservation-grade epoxy resin,[16] using two-part silicone molds made from extant elements (fig. 6).[17] Epoxy was chosen as the medium for these replacement parts due to its light weight, its smooth, nonporous surface, and its flexible working properties.[18] Further, the new epoxy parts would be distinguishable from original ormolu elements by conservators and curators in future examinations.

Reproduction bunches of grapes in various states of completion. The base epoxy material is clear and colorless, so they were painted with a red acrylic layer to improve visibility of the translucent surface during working. Then, the bunches were gilt with genuine gold and a rabbit skin glue liquor and toned with acrylic paints.

The casts were carved and sanded to remove imperfections and improve their fit. Their surfaces were painted with a red coating[19] to improve visibility of the translucent resin during the working process and to fill any air bubbles that had formed in the casts. Then, the casts were gilt using gold leaf and a rabbit skin glue size. Finally, the gilding was toned with acrylic paints to approximate the original ormolu surface (fig. 7). A majority of the recreated components could be mechanically affixed to the wall lights, which eliminated the need to use adhesive on the original material (fig. 8). As a result, the cast components can be easily removed or replaced as necessary in the future.

The reconstructed elements were mechanically affixed using an extant screw that extended through the arm. Note: The base of the screw is visible in white, where it was wrapped in teflon tape to improve contact of the threads and mitigate stripped areas. Image courtesy of Madison Whitesell

With treatment completed, the wall lights were finally brought closer to their original appearance (fig. 9). The nuances of the gilded surface were made visible through the reduction of distracting copper corrosion products, and the missing elements were recreated and integrated seamlessly. A viewer’s eye is no longer drawn to imperfections in condition, which allows for unhindered observation and appreciation of the intricately skilled and laborious craftsmanship of the workshop of Pierre-François Feuchère as executed in this pair of wall lights.

The Walters’ Wall Lights (54.2271 and 54.2272) before and after treatment

[1] Pierre-François Feuchère (French, 1737‒1823) or Jean-Pierre Feuchère (French, 1807‒1852), ca.1787‒1788, J. Paul Getty Museum, acc. no. 78.Df.90.

[2] After F. L. Feuchère père (French, d. 1828), late 18th or early 19th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, acc. no. 1977.1.6-.9.

[3] Unidentified French artist, 1788, Musée du Louvre, acc. no. OA 6524 1-2.

[4] J. Paul Getty Museum, “Pierre Gouthière,” Getty Museum Collection, https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/person/103K7F.

[5] Pierre Verlet, Les bronzes dorés français du XVIIIe siècle, 2nd ed. (Grands Manuels Picard, 1999).

[6] John Whitehead, The French Interior in the Eighteenth Century (Laurence King, 1992).

[7] See note 1; Anne Marian Jones, A Handbook of the Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum (J. Paul Getty Museum, 1965); Verlet, Les bronzes dorés français du XVIIIe siècle, 378–84.

[8] Jacques Robiquet, Gouthière: Sa vie – son oeuvre (Librairie Renouard, 1912); Verlet, Les bronzes dorés français.

[9] Carle Dreyfus, Musée du Louvre: Mobilier du XVIIe et du XVIIIe Siècle (Musées Nationaux, 1922); see note 3 for object information.

[10] Verlet, Les bronzes dorés français.

[11] See note 2.

[12] This paragraph refers heavily to techniques discussed in the following resources: Martin Chapman, “Techniques of Mercury Gilding in the Eighteenth Century,” in David Scott, Jerry Podany, and Brian Considine, eds., Ancient and Historic Metals (Getty Conservation Institute, 1994), 229‒39; Brian Considine and Michel Jamet, “The Fabrication of Gilt Bronze Mounts for French Eighteenth-Century Furniture,” in Terry Drayman-Weisser, ed., Gilded Metals: History, Technology and Conservation (Archetype Publications, 2000), 283‒95; Dimitri Shipounoff, “Picture Framing I: La Reparure,” Museum Management and Curatorship 13, no. 4 (1994): 431‒34, https://doi.org/10.1016/0964-7775(94)90098-1.

[13] Shayne Rivers and Nick Umney, Conservation of Furniture (Routledge, 2003).

[14] David A. Scott, Copper and Bronze in Art: Corrosion, Colorants, Conservation (Getty Conservation Institute, 2002).

[15] Chris Stavroudis, Tiarna Doherty, and Richard Wolbers, “A New Approach to Cleaning I: Using Mixtures of Concentrated Stock Solutions and a Database to Arrive at an Optimal Aqueous Cleaning System,” Western Association for Art Conservation Newsletter 27, no. 2 (May 2005): 17‒28, http://cool.conservation-us.org/waac/wn/wn27/wn27-2/wn27-205.pdf; Chris Stavroudis and Tiarna Doherty, “A Novel Approach to Cleaning II: Extending the Modular Cleaning Program to Solvent Gels and Free Solvents, Part 1,” Western Association for Art Conservation Newsletter 29, no. 3 (September 2007): 9‒15, http://cool.conservation-us.org/waac/wn/wn29/wn29-3/wn29-304.pdf.

[16] HXTAL NYL-1, two-part epoxy resin (cyclohexanol, 4,4’-(1-methylethylidene)bis-, polymer with 2-(chloromethyl)oxirane).

[17] Oomoo 25 (silicone rubber).

[18] Stephen P. Koob, “Tips and Tricks with Epoxy and Other Casting and Molding Materials,” Objects Specialty Group Postprints 10 (2003): 158‒72; Vanessa Muros, Heather White and Özge Gençay-Üstün, “The Use of CopyFlex Food Grade Silicone Rubber for Making Impressions of Archaeological Objects,” Objects Specialty Group Postprints 22 (2015): 184‒204.

[19] Primal WS-24 (acrylic colloidal dispersion in water) and Golden Fluid acrylic paint in cadmium red.