Unidentified artist, “Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive, Germany, ca. 1700–1720, silver, enamel, lacquer, pearl, ruby or red glass, H: 2 3/16 in. (5.6 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, by 1931, acc. no. 57.887

“Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive in the collection of the Walters Art Museum is a small figurine featuring a young boy whose hands are bound behind his back (figs. 1 and 2). Only about two inches high, the figure’s head and arms are composed of deliberately blackened silver, while the tunic and turban are formed from large irregularly shaped pearls that are trimmed with small diamonds and rubies or spinels. There is much that we do not know about this object. It appears to have been purchased by Henry Walters, son of William Walters, founder of the Walters family’s collection and gallery. No provenance information came with it when Henry’s collection entered the museum upon his death in 1931.[1] This figurine, depicting subject matter troubling to contemporary readers, would have been a sought-after luxury item in Northern Europe; objects such as this, composed of precious metals and gemstones, were widely collected and displayed by princely collectors in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. But at some later point during this figure’s journey from its place of origin to Baltimore, it was transformed into a pendant, indicated by a gold hook (bale) that was attached to the upper back, and a fringe of dangling pearls from the tunic’s hemline (fig. 3).[2] Through these later additions, this figure was transformed from a small statue, likely mounted on a pedestal, into a piece of jewelry, evoking even more troubling meanings as an item of personal adornment. This note explores the possible meanings that “Pearl Figure” may have signified or evoked during the early modern era, including interlocking associations between pearls, slavery, colonialism, and racism.

Back of “Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive, acc. no. 57.887

In both material and subject matter, “Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive denotes global trade and European imperialism. The disturbing subject of this figure, a bound African, signifies European global conquest and its desire for control of Indigenous peoples and natural resources in remote colonies. Traditionally, some of the gems used to form this figure were associated with what was considered the “Far East”—a term that connoted an exoticized notion of what was thought to be the foreign and mysterious continent of Asia. The diamonds may have come from India, the primary source for that gem for more than two thousand years, and the red ruby or spinel eyes were associated with regions of Asia.[3] The most prominent feature of this figure are the two large irregularly shaped pearls that comprise its tunic and turban. Pearls were prized and widely traded since antiquity; the richest sources were fisheries in the Persian Gulf and, beginning in the sixteenth century, pearl fisheries in South America, newly discovered by Europeans. The turban would have called to mind parts of the Middle East and Northern Africa, while the dark skin and bound arms reference the continent of Africa, the source of much enslaved labor by the late seventeenth century. Additionally, the figure’s arm bands may have been inspired by widely circulated prints of the Indigenous people of South America.[4] All of these connotations resulted in a constructed concept of exoticism and perceived racial hierarchy, which had developed in the minds of white Europeans as early as the fifteenth century.[5] As Adrienne Childs explains, such imagery, which remained popular in a variety of media for the next two centuries, filters the “Black African through the veil of an imagined Orient.”[6]

“Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive before the fringe of pearls was removed, acc. no. 57.887

Today the erosion of the blackened surface reveals its silver base, but the skin of the figure was originally a deep shade of black, contrasting and highlighting the silver arm bands studded with diamonds, the ruby pendants, the rows of diamonds that form the necklace and decorate the turban, and of course, the pearls. A disturbing point of contrast in this piece, because of the obvious connotations of powerlessness, are the bands that tie the figure’s arms together behind his back.[7] This use of contrast to emphasize the darkness of an African’s skin—and by implication, the whiteness of that of wearer/viewer—was a popular device used in luxury objects, jewelry, furniture, and decorative arts from the sixteenth century to the present day; such objects are commonly referred to as “Blackamoor.”

The origins of the term “Blackamoor” and its usage are not entirely clear.[8] The word, an English term, was originally synonymous with “Moor,” referring to someone from Northern Africa, but it was also associated with Black enslaved individuals and servants from other parts of Africa, who were part of the trans-Saharan Arab slave trade.[9] “Blackamoor” objects were widely produced during the early modern era and range from small statuettes to life-size sculptures in a variety of media. Such figures displayed in homes of the wealthy throughout Europe could have represented their owners’ actual domestic attendants, as well as an enslaved workforce connected to remote landholdings.[10] As Adrienne Childs and Susan Libby contend in their study of imagery of Africans in Europe, such figures stand in for the many unnamed servants in innumerable households; as such they “naturalize, aestheticize, and trivialize the Black labor that facilitated the rise of conspicuous luxury consumption in Europe.”[11] In her study of the “Blackamoor,” Ella Shohat argues that because these figures are usually depicted in postures of humility, they may also attempt to mask white anxieties about “racial mixing, cultural syncretism, and intellectual influence” among Europe and the neighboring continents of Asia and Africa.[12]

Meissen Manufactory (Germany, 1710–present), Modeler: Johann Joachim Kändler (German, 1706–1775), after a composition by Laurent Cars (French, 1699–1771), after a composition by François Boucher (French, 1703–1770), Lady with Attendant, ca. 1740, hard-paste porcelain, gilt-bronze mount, 7 ¼ in. (18.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964, acc. no. 64.101.59 a, b

One popular “Blackamoor” trope is the image of an African person in a domestic setting, which was modeled after actual servants in courts across Europe during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Often dressed in elaborate liveries and other costumes, the presence of these individuals speaks to Europe’s ongoing objectifying fascination with Africa and the Near and Far East. Lady with Attendant, a small porcelain statue created in Germany around 1740, features a richly dressed white woman beside her young Black servant, who wears elegant clothing and a turban (fig. 4). This ornamental vignette, which may have been used as a table setting, would have signified the owner’s prosperity, as well as the enslaved labor and colonial holdings required to produce the bowl of sugar featured on the small side table.[13]

Like the young boy featured in Lady with Attendant, “Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive represents Europe’s paternalistic fascination with young children brought from Africa, often to be showcased in court. In addition to porcelain, the inclusion of these figures was especially popular in courtly portraiture.[14] In her study of slavery and race in Europe and America, Dienke Hondius suggests that wealthy Europeans often preferred children and youths over adults to serve in their homes because they were likely more malleable in the process of molding them into the image of their masters and mistresses.[15] Further, this trend reflects the persistent paternalistic attitudes that Europeans had towards persons of color, as they largely thought of Africans and other non-white individuals as children, without the privileges of adulthood. In this light, when masters cared for their young servants, they could be seen as solicitous and caring, rather than demanding of submission and abusively controlling.[16]

Titian (Italian, ca. 1488/90–1576), Laura Dianti, 1523, oil on canvas, 47 × 37 in. (118 × 93 cm). The Fund Heinz Kisters, Kreuzlingen

While we cannot be certain if “Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive was intended to represent a youthful courtly servant or an enslaved individual, it may be instructive to look at other images of African children created in the early modern era. Beginning around 1520, and continuing for the next two centuries, a number of portraits were produced throughout Europe that feature young pages attending to their mistresses or masters.[17] One of the first such portraits, and a model for those that followed, is Titian’s Laura Dianti, painted around the mid-1520s (fig. 5). Although she was of lower socioeconomic status and a mistress, Dianti is presented as an aristocrat through her elaborate costume and the inclusion of a Black servant in formal livery, who adoringly gazes up at her.[18]

Adriaen Hanneman (Dutch, ca. 1604–1671), Posthumous Portrait of Mary I Stuart with a Servant, 1664, oil on canvas, 51 × 47 in. (129.5 × 119.3 cm). Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands

The pearl earrings that Dianti and her page are wearing were popular accessories during the period, as evidenced by the many depictions of them in art.[19] Pearl jewelry was common for both men and women, but when worn by young Black pages, the whiteness of the gem served as a contrast for the darkness of the wearer’s skin. The pearl earring along with turban, jeweled necklace, and tunic of the “Pearl Figure” of a Captive African functions in the same way. In contrast, when pearls were worn by white women, such as the choker around the throat of Mary I Stuart, it was thought to emphasize her beauty, which was determined by the whiteness and luster of her skin (fig. 6).[20] This emphasis on the difference in skin color between the woman and her young page represents a fetishization of her white skin, which, for white Europeans of the period, symbolized beauty.[21] It was this and other perceived points of differentiation between Europeans and Africans that served as an important part of the formation of Western identity during the early modern era.[22]

Regardless of whether or not the young African in Dianti’s portrait was owned by her, his inclusion in her portrait was an important status symbol, and such images became more and more common during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. And like the Blackamoor objects that were created as stand-ins for actual Black servants and enslaved individuals, these portraits may provide insights into the actual role these individuals played in elevating the status of Northern European courts by calling attention to their owners’ wealth and “adding an exotic touch to princely households and ceremonies.”[23] Because Europeans associated Africa with boundless riches (from which they could profit) and fruitfulness, most of these young servants dutifully offer their mistresses items of luxury, usually jewels or flowers.[24] In Mary Stuart’s portrait, for example, a Black page wraps a string of pearls around her right wrist as he gazes up at her; the nautilus shell and pearls on the side table next to the page’s right elbow connect her fortune with maritime empire. Other symbols of empire featured here include the turban festooned with strings of pearls and feathers, and the feathered cloak that she wears, which was designed to resemble those worn by Indigenous people living in northeastern Brazil. Mary was married to Willem II of Orange, the stadtholder of the Netherlands, which had controlled that region of Brazil from 1630 to 1654.[25]

It is important to note that in addition to emphasizing racial hierarchy, pearls and their depictions in art also signified slavery and Western expansion around the globe.[26] While Spain controlled the Atlantic pearl fisheries, beginning in the early sixteenth century, Portugal exerted control over a number of sites in the Persian Gulf and on India’s southern coast.[27] And although the European imaginary had traditionally associated pearls with the luxury markets of South, Southeast, and East Asia, because of the sheer quantities shipped from Atlantic fisheries in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, pearls came to be associated with the “New World,” or the Americas.[28] As Molly Warsh points out in her study of pearls and the then newly discovered pearl fisheries of Spanish America, as the influx of pearls opened up new markets for the gem, pearls from both the East and the West “mixed and mingled as they traveled the globe.”[29] Almost from Spain’s first contact with the gems, jewel merchants from other parts of Europe were involved in the trade. For example, because they loaned money to the Portuguese crown, German merchants had significant control over this global commodity.[30] Although baroque pearls, which were relatively larger and irregularly shaped, were often referred to as “oriental pearls,” this designation did not refer to their place of origin but rather to the fact that they were saltwater pearls and not those fished in local bodies of water in Europe.[31] Works of art in a variety of media from the sixteenth through the eighteenth century make the connection between pearls and the Americas. One example is a porcelain sugar box produced in Germany around 1760 (fig. 7). A Black woman, wearing only a stylized feather headband and strings of pearls draped around her neck and right arm, sits next to a porcelain sugar pot. Through the allusion to sugar, along with her headdress and pearls, she represents a connection between the Americas and pearls.

Nymphenburg Porcelain Manufactory (German, 1747–present), Modeler: Franz Anton Bustelli (Swiss, 1720–1763), Sugar Box, ca. 1760, hard-paste porcelain, H: 5 5/16 in. (13.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982, acc. no. 1982.60.197a

When Christopher Columbus set out for what he believed was India in 1492, foremost in his mind, and indeed in that of the Spanish monarchy that sponsored him, was the quest for pearls. It was not until his third ocean crossing in 1498, however, that he encountered some of the Indigenous population wearing strings of pearls.[32] This discovery led him to nearby pearl-rich islands, where the local population had fished for oysters and other shells for thousands of years.[33] Importantly, while the Spanish sought pearls as a potential source of wealth, the region’s Indigenous people did not view them in that way; rather, pearls were one of many aspects of nature that formed a connection between the physical and spiritual worlds.[34] In his “biographical” study of pearls, Nicholas Saunders traces how attitudes towards the gem changed its status in the region, from a material with a shamanic function to a commodity, a phenomenon that had a catastrophic effect on the indigenous cultures and peoples.[35]

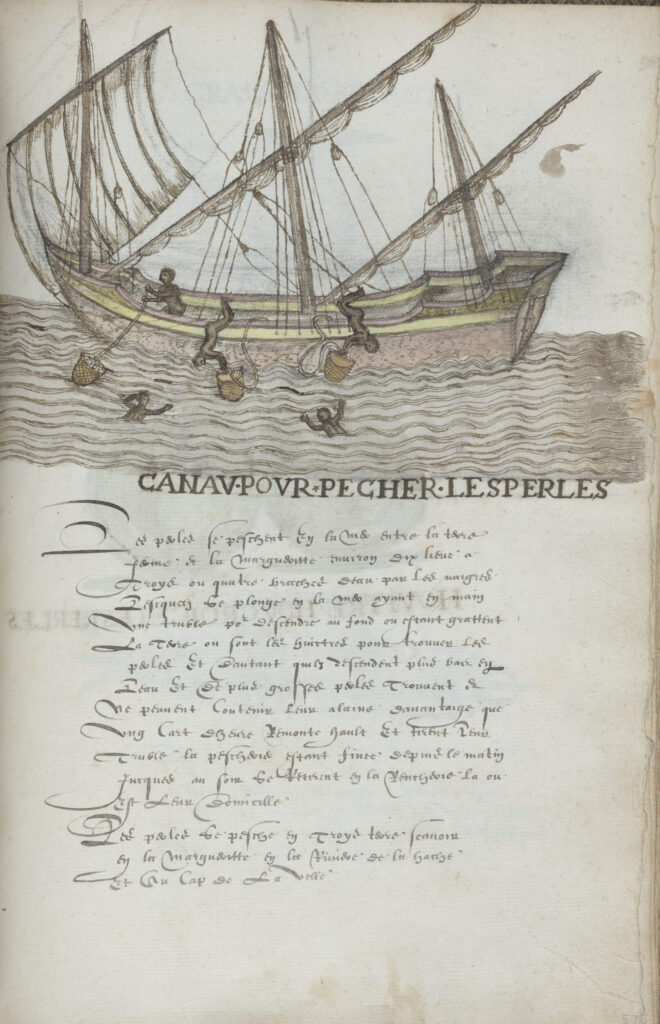

Indeed, Europe’s voracious appetite for the gems set in motion disastrous events for the region’s ecosystem and those who dove for them.[36] Initially, indigenous people of the Americas were forced into pearl diving, and the Spanish pillaged many small islands and conducted extensive slave raids in surrounding settlements to populate their workforce. As a result of these raids and enslavement, along with the introduction of unfamiliar diseases by the European colonizers, by the early sixteenth century, many small islands were depopulated; in fact, within a generation of the Spanish arrival in the Caribbean, some tribes were entirely wiped out.[37] In her study of pearl fishing in the Caribbean during this period, Mónica Domínguez Torres examines contemporary accounts of the Spanish-controlled fisheries.[38] The Spanish historian and governmental appointee to the Caribbean Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés explains how the pearls were extracted in some of the pearl fisheries in the Americas in his Historia general y natural de las Indias, first published in 1524. According to Oviedo, six or seven enslaved Indians were forced to dive for the oysters, while one remained on the boat to keep it steady: “After some time, an Indian returns to the surface and deposits in the boat the oysters in which the pearls are found. He brings those oysters in a string net bag made for this purpose, which the swimmer carries tied down around the waist or neck.”[39] An illustration and description of this process is also found in Sir Francis Drake’s Histoire Naturelle des Indes, from around 1586 (fig. 8).[40]

Canoe for Pearl-Fishing in Histoire Naturelle Des Indes (Drake Manuscript), ca. 1586, chalk, ink, and watercolor on paper, 11 1/2 x 7 3/4 in. (29.3 x 19.7 cm). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, Bequest of Clara S. Peck, 1983, acc. no. MA 3900, fols. 56v–57

In contrast to these descriptive accounts of pearl fishing, the writings of Dominican friar and priest Bartolomé de las Casas are highly critical of the abuses inflicted on the pearl divers in the Caribbean. He describes the long hours they were forced to work, the whippings they suffered, and the many perils of being in the sea for so long, such as shark attacks and ailments caused by water pressure.[41] When the Indigenous population began to die out as a result of overwork, enslaved Africans were brought to the region beginning in the 1520s, and they shortly replaced the Indigenous laborers.[42] The Europeans, who themselves generally could not swim, exploited the many Africans and Indigenous individuals who were well known for their agility in the water.[43] This cruel exploitation of the pearl divers exemplifies one of the worst forms of slavery in the Western Hemisphere.[44] In his comprehensive study of pearls and pearl-fishing, Robin Donkin argues that the Spanish lust for pearls symbolizes the “unparalleled greed of the Age of Discovery.”[45]

Pierre Mignard (French, 1612–1695), Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth with an Unknown Female Attendant, 1682, oil on canvas, 47 1/2 × 37 1/2 in. (120.7 × 95.3 cm). National Portrait Gallery, London, museum purchase, 1878, acc. no. NPG 497

Significantly, not only was enslaved African labor used to gather pearls in the Caribbean, but many of those enslaved may have been bartered for with pearls, then forced into the very labor involved in the acquisition of the gem.[46] This link between slavery and pearls was reinforced once the precious ornaments reached Europe; both enslaved Africans and pearls were prevalent and were considered valuable commodities openly traded in public markets in Portugal and Spain.[47] These markets also furthered the connection of Africa with Black skin and slavery, an association that has persisted for centuries.[48] The link between pearls, maritime hegemony, and slavery is made direct in a portrait of the Duchess of Portsmouth by Pierre Mignard from 1682 (fig. 9). In this painting, the seated duchess drapes her arm maternally around a young Black girl’s shoulder, as she presents her mistress with a conch shell full of pearls and a sprig of coral, all allusions to sea travel and European maritime expansion.[49] According to Marcia Pointon in her study of gems and jewelry, coral and pearls, when viewed together, represent a duality in texture and color and stand for “an economic and social relationship with the sea.”[50] These signifiers of European maritime hegemony in the portrait of the Duchess, mistress to Charles II of England, would have reflected the imperial global status of the British crown.

Unidentified artist, Pendant with a Lion, Germany or Belgium, 1600–1650, pearl, gold, enamel, diamond, ruby, 2 7/8 × 1 15/16 × 3/8 in. (7.36 × 4.94 × 1 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, 1917, acc. no. 57.618

The obsession with pearls, fueled by the unprecedented quantity that entered the market during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, was especially visible in European courts, where princely collectors, who coveted natural objects of all kinds from around the world, vied with each other for the most and best specimens.[51] While all pearls were coveted, baroque pearls, like those that form the body and turban of “Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive, were especially prized. These collections, sometimes called Wunderkammern or chambers of wonders, reflected not only the owner’s wealth and power but also the quest for knowledge and understanding of the universe.[52] Goldsmiths specialized in creating works based on the pearl’s unusual natural shape, and artisans working in Germany were especially renowned for producing such luxury pieces.[53] Art historian Elizabeth Rodini has argued that because their irregular form represented nature’s anomalies, the subjects that these pearls inspired were often fantastical, such as mythological figures, sea monsters, and other creatures.[54] For example, the silversmith who created the Walters’ Pendant with a Lion, likely made in Germany during the first half of the seventeenth century, used the irregular shape of the pearl to form the animal’s torso, which is mounted on either side by the enameled gold head and haunches (fig. 10).

Unidentified artist, Resting Goat, Germany (Frankfurt am Main), before 1706, baroque pearl, gold, silver, gilded, enamel, rubies, diamonds, H. 2 2/3 in. Green Vault, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden, VI 83 f. © Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Unlike the lion pendant, which was meant to be worn, “Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive was originally created as a miniature statuette that would have been mounted on a base. Such figurines, more commonly playful in nature, were inspired by pearl pendants of the previous centuries.[55] Since we do not know the provenance of the Walters’ pearl figure, it may be useful to look at similar works from princely collections in Germany. The largest collection of pearl figures today is found in the Green Vault collection, now part of the State Art Museums in Dresden. This collection was begun in the 1580s but greatly expanded in the early eighteenth century by Augustus the Strong (1670‒1733), who added a number of pearl figures to his treasure chamber.[56] Augustus purchased his works from agents and jewelers who were based in southern Germany, but these artisans often came from different parts of Europe.[57] Typical of one of his pearl pieces is a figure of a male goat, dating from before 1706 (fig. 11). The goat’s body is formed from a large baroque pearl, while the head, legs, and tail are gold. The work is mounted on an elaborate jeweled base that includes a painting of the mythical children Romulus and Remus being nursed by a she-wolf.[58]

Unidentified artist, Pendant in the Form of a Swan, Northern Europe, 16th century, gold, partly enameled, pearls, 2 ½ × 13/8 × 13/16 in. (6.4 × 3.5 × 2.1 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917, acc. no. 17.190.893

In addition to secular and mythological figures, baroque pearls became popular in religious imagery beginning in the sixteenth century. Textual references as far back as the New Testament led to the association of round pearls with Christianity because their whiteness and relative smoothness were linked to the concepts of faith and purity. In a Catholic context, they were often regarded as a metaphor for the Virgin Mary’s own immaculate conception, a beautiful gem formed miraculously in an earthly shell.[59] One sixteenth-century example of the link between baroque pearls and Christianity is Pendant in the Form of a Swan, a work produced in Northern Europe, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 12). The work features a bejeweled swan hanging from a decorative hook. The neck and wings are created from enameled gold, while the feathery underside of the body is formed from a baroque pearl. It is surmised that the swan could symbolize the Society of the Virgin Mary, also called the Order of the Swan, which was founded in the mid-fifteenth century in Germany.[60] A more direct connection between the concept of Mary and the pearl is found in a mid-seventeenth-century pendant of the Madonna, whose entire body and head are formed from a baroque pearl (fig. 13).[61] Draped with a blue star-studded cloak, the pearl Mary is supported by three angels at her feet and surrounded by gold and diamond flame-like rays and small angel heads.

Unidentified Netherlandish artist, Pendant with Monstrous Pearl in the Form of the Madonna, ca. 1640–1650, baroque pearl, gold, enamel, diamonds, 3 2/3 × 2 ½ in. (9.2 × 6.6 cm). Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Kunstkammer, 2105. Photo: KHM-Museumsverband

In her study of pearls in the early modern era, Domínguez Torres argues that pearls, and their religious associations, played an important role in advancing imperial power and global expansion. In Pearls for the Crown: Art, Nature, and Race in the Age of Spanish Expansion, she argues that the gems were “perceived and deployed as a God-given natural resource to be used in the expansion of Christendom.”[62] In this way, European powers could justify their plunder because they claimed it was the duty of the Crown to be the custodian of colonized natural resources.[63] For royal patrons and collectors of luxury artworks that featured baroque pearls, the transformation of the gem and other precious natural resources into an entirely new object for a king’s collection signified the monarch’s own power over nature’s abundance. With the strategic display of such a collection in treasuries like the Green Vault, European princes like Augustus the Strong could project imperial power, as well as the power of the Christian church.

Side of “Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive, acc. no. 57.887

“Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captivemay be seen in light of such projections of power. For many years, the original shape of this figure was obscured by the fringe of pearls attached to the tunic’s hem when it was converted into a brooch (see fig. 3). Unlike items of jewelry, which would be worn, figures such as this one were likely displayed in special cabinets in a Wunderkammer, where they would be studied and admired as natural marvels and works of art. It was only after the additional pearl fringe was removed from the figure’s tunic that its original shape was revealed, giving us a clue to its possible original function. When placed on a flat surface, it becomes apparent that the “Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive is leaning forward, and the bulge on the right side of the pearl gives the impression that he is kneeling on one knee (fig. 14). This posture, along with his bound hands, places him in a position of servitude or subordination.

Unidentified artist, Camel with Two Moors, Germany (probably Frankfurt am Main), 1700–1705, baroque pearls, gold, cold painted, enamel, silver, diamonds, emeralds. 4.8 × 2 × 1 1/3 in., Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Green Vault, Dresden, VI 116. Grünes Gewölbe, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, photo: Jürgen Karpinski

“Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive is unusual for its seriousness amongst pearl figures. For example, Camel with Two Moors from the Green Vault collection features a Black figure astride a camel whose body is formed from a baroque pearl (fig. 15). Painted on the side of the pedestal is a smiling Black man wearing a feathered headdress sitting amongst caskets of jewels and treasures. This commingling of visual references to Africa (the camel and rider) and the Americas (the figures’ stylized feather headdresses) in one piece is typical of many such works of the period. “Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive does not seem to reference the Americas but instead embodies visual tropes from the East or North Africa. In her recent study on this figurine, Domínguez Torres suggests that the figure’s turban and tunic, along with his posture of humility and submission, represent the Christian European princes’ desire to limit the non-Christian Ottoman Empire’s growing military and political advancements in the region.[64] Thus, this statuette of a bound African youth, along with the pearls used to create the figure, served the imperialistic aims of European powers both abroad and closer to home. As we have seen, “Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive conveys layers of overlapping associations of pearls, slavery, and Western hegemony. At the time of the Spanish discovery of pearl fisheries in the Western Hemisphere, stories of their riches captured the imaginations of Europeans, evidenced by portraits of wealthy nobles and merchants wearing pearls or depicted alongside African attendants adorned with the gem. “Blackamoor” objects were widely produced for the wealthy and ruling classes throughout Europe, further communicating expanding understandings of perceived racial hierarchy.

The later conversion of this statuette into a pendant likely obscured the specific political context of its original meaning, but the overt racism conveyed by the Black bound figure would have been clearly legible. “Blackamoor” jewelry amongst the elite classes was fashionable in Europe as early as the sixteenth century, originally in the form of cameos. The ancient art of cameo carving experienced a resurgence during the Renaissance, and artists began to experiment with new darker materials such as onyx or rosewood, which would provide the dark complexion of these figures.[65] Although these cameos were not caricatures, but idealized and distinctive portraits of Africans, as Europeans increasingly possessed Black servants and colonial landholdings, these items of personal adornment may have had the same surrogate function that other “Blackamoor” objects had.[66] Additionally, as Joaneath Spicer observes, by the early seventeenth century, the aesthetic and social regard of images of Black Africans shifted from appreciation of the “exotic other” to simply the “other.”[67]

One form of “Blackamoor” jewelry that persists today is the trope of the bust of a North African prince wearing a bejeweled turban and tunic. Although a few critics view these pieces as showing wealthy Africans in a favorable light, most see them as racially offensive because of their exoticization of people of color.[68] Versions of these images were especially popular in the early to mid-twentieth century when distinguished fashion houses like Cartier designed and produced pendants and other fashion accessories based on the “Blackamoor” bust, and they are still found for sale today through a number of websites that feature antique jewelry and decorative arts.[69] Because “Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive depicts a full figure and not merely a portrait bust or profile, it may be more closely related to “Blackamoor” furniture and decorative arts, some of which do feature African figures in shackles, and like the “Blackamoor” bust pendants, a number of these disturbing figures remain available for purchase today.[70] Some museums that inherited such collections are currently grappling with how to interpret them to their visitors.[71] There is some controversy as to whether or not such vestiges of racism should be removed from public view or exhibited and studied as evidence of the devastating role that white supremacy has played in subjugating people of color.[72] “Pearl Figure” of a Black African Captive, as both a tiny statue for a prince’s collection and as an item of jewelry, certainly functions as such a reminder of that legacy.

Acknowledgments

I want to give a special thanks to curators Jo Briggs and Joaneath Spicer and conservator Angie Elliot for their insightful observations about “Pearl Figure.”

[1] While we do not know the precise circumstances of the purchase of this bound Black figure, it is important to acknowledge that both Henry and his father, William, were supporters of the Confederacy both during and after the Civil War, and their wealth came from businesses that profited from industries that relied on the institution of slavery and its legacies. The connection between Henry and William’s political views and this object, as well as the collection as a whole, is an important topic for further investigation.

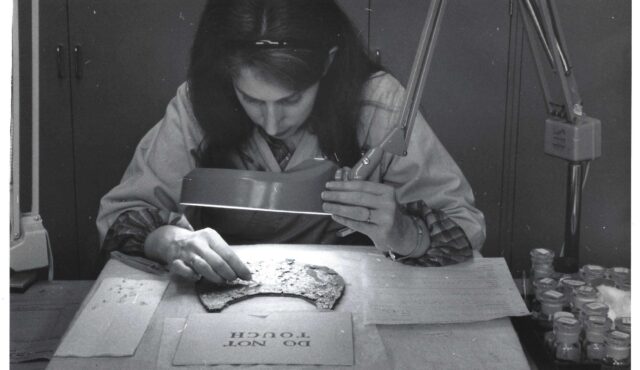

[2] These later additions were removed by museum conservators in 2018 to allow for a thorough object examination.

[3] Diana Scarisbrick, Jewelry in Britain, 1066‒1837: A Documentary, Social, Literary, and Artistic Survey (Michael Russell, 1994), 79‒80.

[4] Helmut Nickel, “The Graphic Sources for the ‘Moor with the Emerald Cluster,’” Metropolitan Museum Journal 15 (1980): 203‒10.

[5] For an exhibition catalogue organized around this concept, see Adrienne L. Childs and Susan H. Libby, The Black Figure in the European Imaginary (The Cornell Museum, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida, 2017). Other publications on imagery of Africans in Europe include Joaneath Spicer, ed., Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe (The Walters Art Museum, 2012) and Elizabeth McGrath and Jean Michel Massing, eds., The Slave in European Art: From Renaissance Trophy to Abolitionist Emblem (Warburg Institute—Nino Aragno editore, 2012).

[6] Adrienne Childs, “Sugarboxes and Blackamoors: Ornamental Blackness in Early Meissen Porcelain,” in The Cultural Aesthetics of Eighteenth-Century Porcelain, ed. Michael Young and Alden Cavanaugh (Ashgate, 2010), 160.

[7] Marcus Wood connects this powerlessness of enslaved persons with torture requisite to subduing them by enforcing a “consciousness of disempowerment and anti-personality.” See Marcus Wood, Blind Memory: Visual Representations of Slavery in England and America, 1780‒1865 (Oxford University Press, 2002), 215.

[8] Emily C. Bartels, “Too Many Blackamoors: Deportation, Discrimination, and Elizabeth I,” Studies in English Literature, 1500‒1900 46 (Spring 2006): 305‒22, at 308; and P. E. H. Hair, “Attitudes to Africans in English Primary Sources on Guinea up to 1650,” History of Africa 26 (1999): 43‒68, at 64‒65.

[9] Although the origins of Moor are themselves unclear, by the early modern era it was commonly used by English speakers to describe Islamic peoples from Northern Africa and Spain.

[10] Paul Kaplan, “Visual Sources of the ‘Blackamoor’ Statue,” in ReSignifications: European Blackamoors, Africana Readings, ed. Awam Amkpa (Postcart, 2017), 49.

[11] Childs and Libby, The Black Figure in the European Imaginary, 38.

[12] Ella Shohat, “The Specter of the Blackamoor: Figuring Africa and the Orient,” The Comparatist 42 (October 2018): 158‒88, at 158.

[13] Childs, “Sugarboxes and Blackamoors,” 167.

[14] David Bindman, “Introduction,” in The Image of the Black in Western Art, Volume 3: From the “Age of Discovery” to the Age of Abolition, Part 1: Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque, ed. David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014), 2.

[15] Dienke Hondius, Blackness in Western Europe: Racial Patterns of Paternalism and Exclusion (Transaction Publishers, 2014), 34.

[16] Hondius, Blackness in Western Europe, 3‒4 and 36.

[17] Elmer Kolfin, “Portraits and Servants,” in Black is Beautiful: Rubens to Dumas, ed. Esther Schreuder and Elmer Kolfin (De Nieuwe Kerk; Waanders, 2008), 241; and Kaplan, “Visual Sources of the ‘Blackamoor’ Statue,” 50.

[18] Victor Stoichita, “The Image of the Black in Spanish Art: Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries,” in Bindman and Gates, The Image of the Black, Volume 3, 109.

[19] Elizabeth McGrath, “Caryatids, Page Boys, and African Fetters: Themes of Slavery in European Art,” in McGrath and Massing, The Slave in European Art, 3‒38, at 17.

[20] Kim F. Hall, Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England (Cornell University Press, 1995), 247.

[21] Hall, Things of Darkness, 211.

[22] Allison Blakely, “Problems in Studying the Role of Blacks in Europe,” Perspectives on History [American Historical Association Newsletter] (May/June 1997), https://www.historians.org/perspectives-article/problems-in-studying-the-role-of-blacks-in-europe-may-1997/#:~:text=A%20discussion%20of%20the%20influence,evidence%20of%20an%20African%20influence?; and Simon Gikandi, Slavery and the Culture of Taste (Princeton University Press, 2011), 41.

[23] Rashid-S. Pegah, “Real and Imagined Africans in Baroque Court Divertissements,” in Germany and the Black Diaspora: Points of Contact, 1250‒1914, ed. Mischa Honeck, Martin Klimke, and Anne Kuhlmann (Berghahn Books, 2013), 74‒91; Anne Kuhlmann, “Ambiguous Duty: Black Servants at German Ancien Regime Courts,” in Germany and the Black Diaspora, 57; and Mónica Domínguez Torres, Pearls for the Crown: Art, Nature, and Race in the Age of Spanish Expansion (Penn State University Press, 2024), 280.

[24] Hall, Things of Darkness, 232.

[25] See Gert Oostindie and Bert Paasman, “Dutch Attitudes towards Colonial Empires, Indigenous Cultures, and Slaves,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 31 (Spring 1998), 350, and https://www.mauritshuis.nl/en/our-collection/artworks/429-posthumous-portrait-of-mary-i-stuart-1631-1660-with-a-servant.

[26] Several recent publications convincingly outline the close connection between pearls, slavery, and European imperial expansion. See Molly Warsh, American Baroque: Pearls and the Nature of Empire, 1492–1700 (Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and the University of North Carolina Press, 2018); Mónica Domínguez Torres, Pearls for the Crown; and Mónica Domínguez Torres, “Pearl Fishing in the Caribbean: Early Images of Slavery and Forced Migration in the Americas,” in African Diaspora in the Cultures of Latin America, the Caribbean, and the United States, ed. Persephone Braham (University of Delaware Press, 2015), 73–82.

[27] Domínguez Torres, Pearls for the Crown, 222; Anna Beatriz Chadour-Sampson with Hubert Bari, Pearls (V&A Publishing, 2013), 15; and Pedro Dias, “The Portuguese in the Orient,” in Exotica: The Portuguese Discoveries and the Renaissance Kunstkammer, ed. Helmut Trnek and Nuno Vassallo e Silva (Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 2001), 12‒19.

[28] Nicholas J. Saunders, “Biographies of Brilliance: Pearls, Transformation of Matter and Being c. AD 1492,” World Archaeology 31, no. 2 (October 1999): 251; Domínguez Torres, Pearls for the Crown, 20; and Warsh, American Baroque, 2.

[29] Warsh, American Baroque, 41.

[30] Warsh, American Baroque, 56.

[31] Domínguez Torres, Pearls for the Crown, 257.

[32] Warsh, American Baroque, 31.

[33] Michael Perri, “‘Ruined and Lost’: Spanish Destruction of the Pearl Coast in the Early Sixteenth Century,” Environment and History 15 (May 2009): 130.

[34] Saunders, “Biographies of Brilliance” 245.

[35] Saunders, “Biographies of Brilliance,” 244.

[36] Perri, “‘Ruined and Lost,’” 130.

[37] William F. Keegan, The People Who Discovered Columbus: The Prehistory of the Bahamas (University Press of Florida, 1992), 222; and Alex Borucki, “Trans-Imperial History in the Making of the Slave Trade to Venezuela, 1526‒1811,” Itinerario 36, no. 2 (2012): 31.

[38] Domínguez Torres, “Pearl Fishing in the Caribbean,” 73‒82.

[39] Quoted in Domínguez Torres, “Pearl Fishing in the Caribbean,” 75.

[40] Histoire Naturelle Des Indes, also known as the Drake manuscript, ca. 1586. The Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Bequest of Clara S. Peck, 1983, acc. no. MA 3900.

[41] Domínguez Torres, “Pearl Fishing in the Caribbean,” 76.

[42] Linda A. Newson and Susie Minchin, From Capture to Sale: The Portuguese Slave Trade to South America in the Early Seventeenth Century (Brill, 2007), 5; and Kevin Dawson, “Enslaved Swimmers and Divers in the Atlantic World,” The Journal of American History 92, no. 4 (March 2006): 1327‒55.

[43] Dawson, “Enslaved Swimmers and Divers.”

[44] Domínguez Torres, “Pearl Fishing in the Caribbean,” 75.

[45] Robin A. Donkin, Beyond Price: Pearls and Pearl-Fishing: Origins to the Age of Discoveries (American Philosophical Society, 1988), 333. The dangers and hardships suffered by enslaved Indigenous laborers, and later, enslaved Black Africans who were brought to America in large numbers for that purpose, were well-known by most Europeans, and may have added to the pearls’ value. For example, in his Natural History, Pliny the Elder connected the desire for pearls with the dangers of diving for them. See Warsh, American Baroque, 14; Mónica Domínguez Torres, “Mastery, Artifice, and the Natural Order: A Jewel from the Early Modern Pearl Industry,” in The Oxford Handbook of History and Material Culture, ed. Ivan Gaskell and Sarah Anne Carter (Oxford University Press, 2020), 65; and Domínguez Torres, Pearls for the Crown, 241.

[46] Warsh, American Baroque, 47‒48; and Newson and Minchin, From Capture to Sale, 45.

[47] Carmen Fracchia, “The Urban Slave in Spain and New Spain,” in McGrath and Massing, The Slave in European Art, 195.

[48] T. F. Earle and K. J. P. Lowe, Black Africans in Renaissance Europe (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 11.

[49] Warsh, American Baroque, 222.

[50] Marcia Pointon, Brilliant Effects: A Cultural History of Gem Stones and Jewellery (Yale University Press, 2009), 108.

[51] Saunders, “Biographies of Brilliance,” 251.

[52] Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150‒1750 (Zone Books, 2001), 86; and Rudolf Distelbeger, “‘Quanta Rariora Tanta Meiora’: The Fascination of the Foreign in Nature and Art,” in Trnek and Vassallo e Silva, Exotica, 20‒25, at 22.

[53] Donkin, Beyond Price, 276.

[54] Elizabeth Rodini, “Baroque Pearls,” in “Renaissance Jewelry in the Alsdorf Collection,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 25, no. 2 (2000): 68.

[55] Dirk Syndram, Gems of the Green Vault in Dresden (Koehler & Amelang, 2000), 213.

[56] Syndram, Gems of the Green Vault in Dresden, 9.

[57] Dirk Syndram, “Monument to a Royal Collector—August the Strong and his Grünes Gewölbe,” in The Dream of a King: Dresden’s Green Vault, ed. Dirk Syndram and Claudia Brink (Hirmer Verlag, 2012), 38‒40; and Syndram, Gems of the Green Vault in Dresden, 133.

[58] Syndram and Brink, The Dream of a King, cat. no. 41.

[59] A variety of legends of pearls and their origins have existed around the world since antiquity, sometimes connected to the tears of gods, or other heavenly phenomena like thunder and moonlight. Depending on the context in which they appear, pearls could also be symbolic of vanity because of their use as a bodily adornment. See Pointon, Brilliant Effects, 114; and E. de Jongh, “Pearls of Virtue and Pearls of Vice,” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 8, no. 2 (1975‒1976): 69‒97, at 80‒81.

[60] Elizabeth Cleland, “Pendant in the Form of a Swan,” 2017, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/193680.

[61] Domínguez Torres, Pearls for the Crown, 80.

[62] Domínguez Torres, Pearls for the Crown, 94.

[63] Domínguez Torres, Pearls for the Crown, 90‒94.

[64] Domínguez Torres, “Mastery, Artifice, and the Natural Order,” 66; and Dirk Hoerder, “Africans in Europe: New Perspectives,” in Honeck, Klimke, and Kuhlmann, Germany and the Black Diaspora, 236.

[65] Joaneath Spicer, “European Perceptions of Blackness as Reflected in the Visual Arts,” in Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe, 47‒50.

[66] Stoichita, “The Image of the Black in Spanish Art,” 153.

[67] Spicer, “European Perceptions of Blackness,” 47.

[68] See Cris Notti, “The Truth and History of the Blackamoor,” Cris Notti Jewels (June 15, 2022), last accessed August 12, 2024, https://www.crisnottijewels.com/the-truth-and-history-of-the-blackamoor/; and Erica Gonzales, “Princess Michael of Kent Wore a Racist Brooch to Lunch with Meghan Markle,” Bazaar (December 21, 2017), last accessed August 12, 2024, https://www.harpersbazaar.com/celebrity/latest/a14481097/princess-michael-of-kent-racist-brooch/.

[69] https://www.ericoriginals.com/product-page/cartier-blackamoor-brooch-enamel

[70] Emily Symington, “Racist Porcelain: The Trend of the “Blackamoor” in Europe, Varsity (August 29, 2020), https://www.varsity.co.uk/arts/19751.

[71] See Amkpa, ReSignifications; Anneke Rautenbach, “Gaudy, Sure—But Racist Too? Unpacking Centuries of ‘Blackamoor’ Art,” NYU Arts and Culture (January 2017), https://www.nyu.edu/about/news-publications/news/2015/july/awam-amkpa-on-blackamoors-at-la-pietra.html; and Marlise Brown, “The Linsky Project: Reinterpreting Porcelain Figures,” The Met (April 12, 2023), https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/articles/2023/4/linsky-porcelain.

[72] Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow (Penguin, 2019), 193.