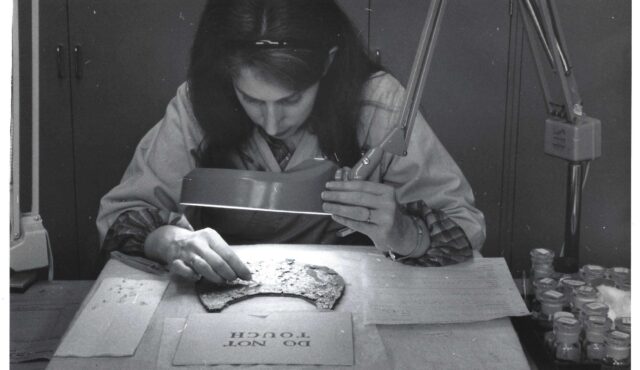

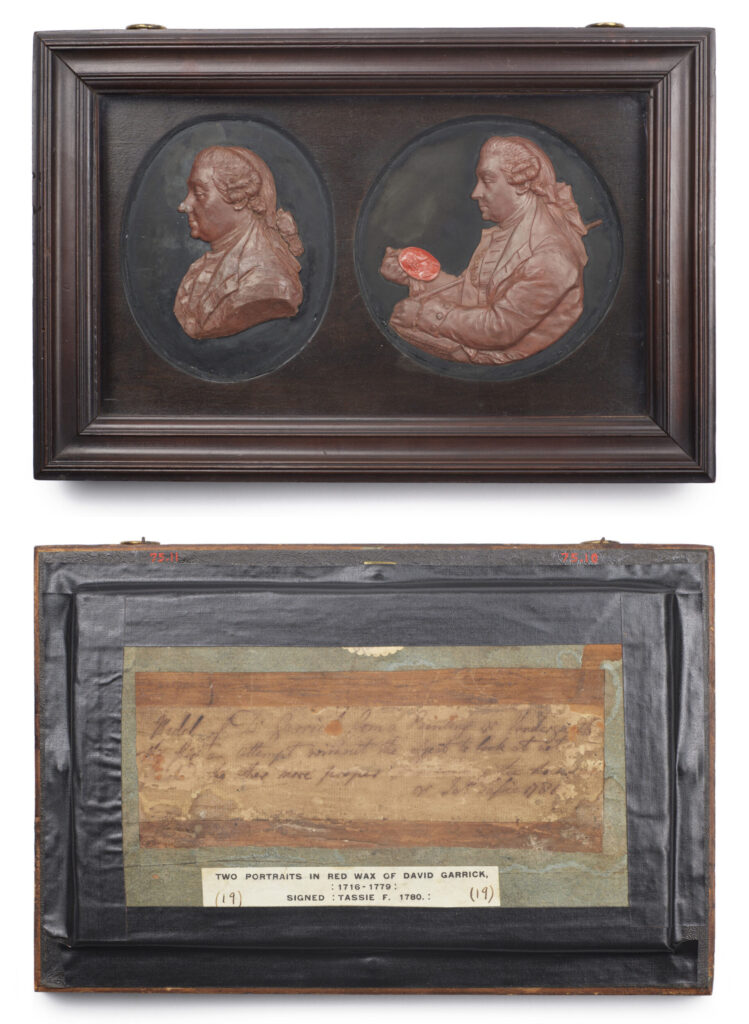

The Walters Art Museum has in its collection an unusual pair of wax relief profile portraits (acc. nos. 75.10 and 75.11) of the celebrated eighteenth-century Shakespearean actor David Garrick (1717–1779) modeled by artist and entrepreneur James Tassie (1735–1799). The reliefs both depict Garrick in his role as steward of the 1769 jubilee celebration of William Shakespeare; one version (75.11) is inscribed with the date 1780. The reliefs are mounted side by side, framed together, and inscribed on the reverse in Tassie’s hand with an additional date of 1781 (fig. 1). Museum records indicate that these portraits were purchased from the London dealer George Robinson Harding (active ca. 1887–1931) in 1911 by Henry Walters (1848–1931) or one of his agents.[1]

James Tassie (Scottish, 1735–1799), Profile Portraits of David Garrick, 1780, colored beeswax, red sulfur, paper, glass, wood, 7 13/16 × 11 1/32 × 1 3/16 in. (19.8 × 28 × 3 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, 1911, acc. nos. 75.10 & 75.11, front and back

The reliefs are not widely known, as they have seldom been exhibited and have previously only been described in an 1894 publication.[2] However, they are an important record of James Tassie’s working methods and techniques. The pair represent an initial sketch and a finished wax model for his commercially produced medallions of Garrick in white glass (fig. 2).[3]

James Tassie (Scottish, 1735–1799), David Garrick, 1780, glass paste, 4 1/2 × 4 3/16 in. (11.4 × 10.6 cm). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, acc. no. B2001.2.361

James Tassie was born near Glasgow in 1735. He initially trained as a stonemason but went on to a fine arts education at the Foulis Academy in Glasgow, where he learned techniques of modeling and casting in plaster. In 1763 he relocated to Dublin, where he worked as an assistant to Dr. Henry Quinn, from whom he learned techniques for imitating ancient carved gems, both cameos and intaglios. Together, the two developed a glass with a low melting point suitable for molding and casting that Tassie went on to employ throughout the remainder of his career.[4] In 1766 he relocated to London, where he opened a shop specializing in reproductions of carved gemstones, achieving considerable renown and expanding his stock to include more than 15,800 models by 1791 and approximately 20,000 by the time of his death in 1799.[5]

Though Tassie’s reproductions of cameos and intaglios brought him commercial success, it was his portrait reliefs that brought him artistic acclaim.[6] He exhibited wax models at the Society of British Arts beginning in 1767 (one year after relocating to London), followed by “enamel” (opaque glass) portraits the following year. In 1769 he began to display his work in the annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy, showing portrait reliefs every year up to and including 1791, with the exception of 1780.[7] The discrepancy in dates on the finished wax of Garrick (1780) and the inscription on the reverse of the frame (1781) is therefore of some interest; it is tempting to think that the wax portraits were mounted and framed for the Royal Academy exhibition in 1781, though Tassie’s exhibits in this year are not recorded with specificity, so this cannot be proven.

The first relief (acc. no. 75.10, mounted at left in the frame) shows Garrick in profile, facing left and gazing downward, with a portion of his chest and a truncated shoulder. The relief is modeled in reddish-brown wax, with tool marks in evidence on the surface, especially in the clothing, which has been somewhat roughly if expressively sketched. The wax relief is mounted to an oval of transparent glass and backed with a very dark paint or painted paper.

The second relief (acc. no. 75.11) takes a similar perspective, but here Tassie has included the arms, hands, and torso of the actor as well. Garrick’s left hand, resting upon a book or plinth, holds a thin staff tucked under his right shoulder, while in his right hand he holds a portrait medallion in relief of William Shakespeare facing right. The medallion, rather than being modeled in the wax, is a red sulfur cast of an intaglio inserted into the composition. The portrait is inscribed on the edge of the plinth below the left hand: “[G]ARRICK STRAT. IUBILEE 1769 / [V]ANDERGUCHT PINXIT / Tassie F. 1780.”[8] The relief is mounted to a circle of transparent glass and backed with the same dark paint or painted paper as its mate.

The pair of mounted reliefs are in turn mounted within a glass-fronted wood frame equipped with two brass rings at the top for suspension. Pasted to the reverse is a strip of laid paper inscribed in ink: “Model of D. Garrick from a painting by Vandergucht / the first an attempt without the object to look at not / finished the other more proper [. . .] the shakespear / Jas. Tassie 1781.”[9] Tassie was evidently in the habit of annotating the reverse of his portrait reliefs and even his shop furniture, as surviving examples attest.[10]

To create his portrait medallions, Tassie sculpted beeswax, often bulked with fillers and partly plasticized by the addition of turpentine.[11] From the finished wax relief, a mold was taken in plaster; from this a master relief was cast in sulfur, often bulked and colored with vermilion or lead. From the sulfur master, molds were then taken with a mixture of plaster of Paris and diatomaceous earth (also known as Tripoli). When these molds had set, they were placed face up in crucibles with a slab of glass above and heated in a furnace; when the glass had softened sufficiently, it was pressed into the mold with an iron spatula. The glass was then annealed (cooled very slowly) to prevent cracking; once annealed, the mold was broken away.[12] Tassie seems to have employed this process for casting portrait reliefs in glass beginning in 1768, though his initial forays produced only the profile, not the complete medallion.[13] By 1773–74 Tassie was experimenting with creating full medallions, typically oval, though sometimes circular, as in the case of the Garrick portrait. The difficulty of the process is attested to by an inscription on the reverse of a framed enamel relief of Sir John English Dolben, 4th Baronet of Finedon, created at that time, now in the National Galleries Scotland (acc. no. PG1282), which reads, in part, “This was the very first attempt of making large Paste impressions but cracked by not being long enough annealed. Tassie F.”[14] The trouble and expense are also reflected in the prices Tassie charged for these larger medallions, as listed in the foreword to his 1791 catalogue by Rudolf Erich Raspe: “Relievo Impressions in white Enamel . . . from large Gems, Bas Reliefs, Portraits etc. from 5 s to £1 1s (Not exceeding four inches diameter) / Impressions of this size in high relief are charged in proportion to the difficulty.”[15]

Unidentified artist after Benjamin van der Gucht (British, 1753–1794), David Garrick in his regalia as Steward of the Stratford Jubilee, 1769, n.d., Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum, acc. no. 2001.137

The Walters’ wax portraits are based on a painting by Benjamin van der Gucht (1753–1794) depicting David Garrick as steward of the Shakespeare Jubilee, held September 6–7, 1769, in Stratford-upon-Avon (fig. 3). The original painting, executed in that same year, was owned by John Spencer, 1st Earl Spencer (1734–1783),[16] though it became better known through a widely circulated mezzotint (monochromatic print with soft gradations of tone) by Joseph Saunders, first printed June 24, 1773, and thereafter sold in his shop on Compton Street, London (fig. 4).[17] While Tassie typically modeled his portrait reliefs from life,[18] he occasionally relied on paintings or prints, transforming a two-dimensional image back into a three-dimensional likeness.[19] As Garrick died on January 20, 1779, and the finished wax is dated 1780, it seems almost certain that Tassie used the Saunders print as inspiration to create his portraits of the actor.[20]

Joseph Saunders (British, active 1772–1808) after Benjamin van der Gucht (British, 1753–1794), Mr. Garrick as Steward of the Stratford Jubilee September 1769, 1773, mezzotint, 13 5/16 × 11 3/16 in. (28.4 × 38.8 cm). The British Museum, acc. no. 1902,1011.4098

In Van der Gucht’s painting and the later Saunders print, Garrick holds the carved wood medallion and ceremonial wand presented to him by the town clerk of Stratford, William Hunt, in recognition of his role as steward of the 1769 Shakespeare Jubilee as well as his donation of a statue of Shakespeare to the new Stratford Town Hall.[21] The medallion and wand were carved from a mulberry tree that was said to have been planted by William Shakespeare. The original medallion, preserved in the collections of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust,[22] is an oval with a profile portrait of Shakespeare carved in relief, framed in gold. The medallion as it is shown in the Van der Gucht painting and the Saunders print features the profile of Shakespeare, facing right. [23] The Jubilee took as its motto “We ne’er shall look upon his like again,” and many souvenirs of the event are inscribed with this verse from Hamlet; an especially interesting example is an enamel medallion in the collections of the Folger Shakespeare Library.[24] One face bears a portrait of Shakespeare together with the Jubilee motto; the opposite side bears a portrait of Garrick in the guise of Hamlet with the motto “Who held the mirror up to nature.” The doubleness of that medallion, juxtaposing Garrick and Shakespeare, is emphasized by the text of the mottoes, calling attention to the acts of looking and mirroring.[25] These aspects are further emphasized in the Van der Gucht painting and its subsequent print, in which Garrick is depicted gazing contemplatively at the relief of Shakespeare, who appears to gaze back as if in communion with the actor across time and media.

Detail image of drawer XX with Shakespeare and Garrick portraits in red sulfur. Number 2818, a cast of an engraved portrait of Shakespeare by Wray, is second from left on the bottom row.

James Tassie (Scottish, 1735–1799), Oak Cabinet Containing Sixty Drawers of Gem Impressions in Red Sulfur, 1766–1776, wood (oak), red sulfur, brass, paper, 20 × 30 × 14 in. (50.8 × 76.2 × 35.56 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Gift of Mrs. Thomas R. Boggs, 1942, acc. no. 42.1449

Throughout his career, Garrick was determined to associate his image and reputation with that of Shakespeare, not only on the stage but also through visual media, especially prints, medals, and portrait cameos.[26] Indeed, the conceit of Garrick doubled with the profile of Shakespeare had already been established in a painting he himself commissioned from the acclaimed portraitist Thomas Gainsborough (1727‒1788) that shows Garrick together with a bust of the Bard that he presented to Stratford on the occasion of the 1769 Jubilee. The painting is now lost,[27] but it was widely known through a mezzotint print.[28] Though rather different in composition, the intense doubled gaze between the two figures was also present in carved gems,[29] as well as reproductions of cameos and intaglios sold by Tassie[30] and others.[31] The link between Garrick and Shakespeare, firmly cemented in the public imagination by his stage performances, the Jubilee, and subsequent dissemination of mass media, seems to have carried over into Tassie’s own catalogue of wares, in which portraits of Shakespeare are immediately followed by those of Garrick (fig. 5).[32] Several examples in Tassie’s inventory feature overlapping profiles of both Garrick and Shakespeare, perhaps also loosely inspired by the Gainsborough portrait.[33]

Tassie’s two versions of the wax portrait, together with the inscription on the reverse of the frame, show how strongly associated Garrick was with Shakespeare by the time of the actor’s death. Tassie’s written inscription assessing “the first an attempt [acc. no. 75.10] without the object to look at” as inadequate and therefore “not finished,” yet “the other [acc. no. 75.11] more proper” with “the shakespear [sic]” suggests that he felt the likeness and perhaps even the identity of the sitter were not clearly communicated without showing Garrick gazing at the subsidiary portrait of Shakespeare (clearly the “object” to which Tassie refers). Very few of Tassie’s portrait reliefs depict the sitters with attributes or other paraphernalia; the vast majority are truncated profiles in contemporary garb or else in a classicizing style. Yet it is worth considering that the medallion of Shakespeare gazed upon by Garrick may have held a special interest for Tassie, as he made his trade in the manufacture and sale of such portraits in relief. It seems he must have been alive to the resonances of this object, as he chose to incorporate into this wax model a profile portrait of Shakespeare that is a carefully trimmed red sulfur cast,[34] cannily inserting his own merchandise into a new work of art for further reproduction in what is seemingly a completely unique instance among his oeuvre.[35] The model for the sulfur cast appears to be number 2818 in the 1775 Tassie catalogue, described as “Shakespeare, cornelian (by Wray).”[36] The engraved gem from which the sulfur was taken bears a close enough resemblance to the original mulberry medallion presented to Garrick in 1769 to warrant consideration that the gem may have been inspired by representations of the medallion in other media,[37]—lending a further layer of nested references to Tassie’s wax portrait.

Tassie’s finished wax relief departs from the Van der Gucht painting and Saunders print in one significant aspect, partly dictated by the medium and Tassie’s process for reproduction. In the painting and print, Garrick rests the mulberry-wood wand over his left shoulder; however, in the wax it is tucked under his right arm. Tassie likely repositioned the wand because it would be difficult if not impossible to render it in high relief or partly in the round in the wax, or, more pertinently, in the casts taken from it. While this positioning would be somewhat awkward in real life, it simplifies the three-dimensional composition of the relief and facilitates subsequent molding and casting to produce multiples in other media.

The two wax relief portraits of David Garrick are unusual examples of Tassie’s working process, preserving an initial attempt that he described as “not finished” together with the final model for the commercial production of glass medallions and reliefs. The insertion of the red sulfur impression of Shakespeare as a representation of the Jubilee medallion is a remarkably playful and self-referential flourish on Tassie’s part, one that has no parallel among his other portrait reliefs. It is also potentially a comment on the intense interplay of late eighteenth-century visual culture, drawing attention to the representations and translations of the original mulberry-wood medallion through painting, print, engraved gem, sulfur impression, finished wax model, and (implicitly) the multiple glass reproductions of Garrick’s portrait that Tassie offered for sale.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Earl Martin, the Deborah and Phillip English Curator of Decorative Arts, Design, and Material Culture, and Jo Briggs, Jennie Walters Delano Curator of 18th- and 19th-Century Art, for their interest in these portraits and for their thoughtful comments on early drafts of this note.

[1] Harding succeeded William Wareham in his business dealing in antiques and curiosities first at Charing Cross Road and later at St. James’ Square, London. Harding sold a large number of items to Henry Walters in 1911 and subsequent years, as is recorded in annotated photo albums now in the Walters Art Museum Archives. For more on Harding, see the British Museum records for “George R Harding”; and Jessica Harrison-Hall, “Oriental Pottery and Porcelain,” in A. W. Franks: Nineteenth-Century Collecting and the British Museum, eds. Marjorie Caygill and John Cherry (British Museum, 1997), 229, no. 50.

[2] See entry no. 146, “Garrick, David” in Gray, “Catalogue of Medallions Representing Modern Personages Modeled by James and William Tassie or Existing in their Pastes,” included as an appendix to his 1894 biography of James and William Tassie, James and William Tassie: A Biographical and Critical Sketch with a Catalogue of their Portrait Medallions of Modern Personages (London, 1894). The pair of portraits were described as “in the possession of Mr. Jefferey Whitehead.” This is likely a reference to the British stockbroker and collector Jeffrey Whitehead (1831–1915); he donated a collection to the British Museum in 1905. See the British Museum records for “Jeffrey Whitehead.” Nothing further is known of the portraits’ whereabouts between 1781 and 1894.

[3] See Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, acc. no. B2001.2.361, for a medallion in white glass and National Galleries of Scotland, acc. no. PG474, for a medallion in plaster. Separate white glass portrait reliefs mounted to colored glass medallions were also produced, as was at least one plaster of the head and truncated shoulders only (National Galleries of Scotland, acc. no. PG1903).

[4] Analysis has shown it is essentially a lead potash glass with colors produced by a variety of metallic salts. See Gray, James and William Tassie, 7; and James Holloway, James Tassie, 1735–1799 (National Galleries of Scotland, 1989), Appendix A, for analytical results.

[5] Rudolf Erich Raspe, A Descriptive Catalogue of a General Collection of Ancient and Modern Engraved Gems, Cameos as well as Intaglios [. . .] (London, 1791), digitized online by the University of Oxford, alongside a database of all the impressions known to exist from James Tassie; Gray, James and William Tassie, 26.

[6] Gray (1894) includes in his catalogue 493 examples of portrait reliefs attributable to James Tassie and his nephew William Tassie. The large majority of these are by James Tassie; the 1791 Raspe catalogue lists 114 “Portraits in Wax.”

[7] Gray, James and William Tassie, 33.

[8] The lower edge of the portrait has been trimmed into a semicircle, apparently cutting through the first letters of the first and second lines.

[9] The inscription is now rather abraded, which makes it somewhat difficult to decipher, though recent digital photography with reflected infrared radiation and long-wave ultraviolet induced visible fluorescence has enabled a better reading. Gray transcribed the text as, “Mould of D. Garrick from a painting by Vandergucht the first attempt without the object to look at . . . the other more proper. . . Jas Tassie 1781” (James and William Tassie, 107). His use of the word “mould” is not correct; the inscription certainly reads “model.”

[10] For example, see a portrait relief of Sir John English Dolben, 4th Baronet of Finedon, ca. 1773–1774, now in the National Galleries of Scotland (acc. no. PG1282), inscribed on the reverse and signed by Tassie. An oak cabinet in the Walters collection (acc. no. 42.1449) containing sixty drawers with 3,824 red sulfur impressions, likely to have been used by James Tassie in his London shop between 1775 and 1791, bears an inscription on the underside of drawer “CC”: “London; 23rd; Apr; 1776 / Cleaned these Sulfurs.”

[11] John P. Smith, James Tassie, 1735–1799, Modeller in Glass: A Classical Approach (Mallett & Son Antiques,1995), 21.

[12] Smith, James Tassie, 21–22. Tassie referred to his transparent glass as “paste” and to opaque glass as “enamel,” terminology that has occasionally caused confusion among subsequent authors and connoisseurs.

[13] Gray, James and William Tassie, 37. The profiles were mounted to glass backed with painted paper, similar to the wax models, acc. nos. 75.10 and 75.11.

[14] Gray, James and William Tassie, 37.

[15] Raspe, A Descriptive Catalogue, lxxv. These 1791 prices are approximately equivalent to $32–$134 in 2024 US dollars as calculated by the Bank of England Inflation Calculator. Inflation calculator | Bank of England (accessed 11/26/2024).

[16] John, 1st Earl Spencer, and his wife Georgiana, Countess Spencer, were friends of Garrick’s and traveled with him in Italy. A marble bust of Garrick by Joseph Noelkens was carved during their stay in Rome and is today at Althorp, the Spencer family’s estate in Northamptonshire. For a discussion of the artworks connecting the Spencers with Garrick, see Peter Walch, “David Garrick in Italy,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 3, no. 4 (Summer 1970): 523–31.

[17] See the British Museum, acc. no. Ee,3.155, for one example. The original painting remains at Althorp. A copy of the painting, either by or after Van der Gucht, also exists and is now in the Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum collection, acc. no. 2001.137.

[18] Tassie was widely praised for the swiftness and ease with which he captured the likeness of a sitter, a practice recorded by Thomas Walker, who sat for a portrait by Tassie in 1798: “He takes three sittings, the two first about an hour each, the third not half an hour” (Gray, James and William Tassie, 40).

[19] Gray, James and William Tassie, 38.

[20] Given that the print was available in London, it is unlikely that Tassie would have traveled to Northamptonshire to view the painting at Althorp. Saunders’s shop in Compton Street was not far from Tassie’s, located at “No. 20 to the east side of Leicester Fields” from 1778 to 1799 (Gray, James and William Tassie, 34).

[21] Garrick commissioned John Cheere to execute a copy of Peter Scheemakers’s 1741 statue of Shakespeare at Westminster Abbey. While a variety of festivities were planned, torrential rains prevented many from happening; consequently, Garrick’s recitation of an “Ode to Shakespeare” formed the main event. The recitation itself was commemorated in several paintings that were subsequently reproduced in prints, as well as restaged for ninety-one successful performances at Garrick’s home theater on Drury Lane in London. See Metropolitan Museum of Art, object number 53.600.4490, for one such print by Caroline Watson after a painting by Robert Edge Pine; also Shakespeare Birthplace Trust object number SBT 1993-31/180 for a more realistic print. In both prints Garrick is shown wearing the mulberry-wood medallion of Shakespeare around his neck.

[22] Object number SBT 1961-14. The medallion was made by Thomas Davies of Birmingham.

[23] This carved wood medallion was also reproduced in a circular format by V. Westwood in silver; one such example, mounted in a wood case of the same mulberry tree supposedly planted by Shakespeare, may be found in the British Museum, acc. no. 1864,0816.5, inscribed in the wood “Jubilee at Stratford in honour and to the memory of Shakespeare Sept 1769 D.G. [David Garrick] Steward”; see also the British Museum, acc. no. MG.1522, for another example by the same maker.

[24] Inv. no. ART 241260.

[25] This same doubleness is present in the iconography of the “Garrick casket” also carved by Davies from wood of the same apparently inexhaustible mulberry tree in which the official document granting “Freedom of the Borough” of Stratford was presented to Garrick in 1768; the front of the casket features a personification of Stratford holding a bust of Shakespeare; the back shows Garrick in the guise of Lear raging at the storm. The casket and document are both now in the British museum, acc. nos. 1864,0816.1 and 1864,0816.2, respectively. For a discussion of the casket, its contents, and its presentation to Garrick, see Hugh Tait, “Garrick, Shakespeare, and Wilkes,” The British Museum Quarterly 24, no. 3/4 (December 1961):100–107.

[26] Heather McPherson, “Garrickomania: Garrick’s Image,” Folgerpedia, accessed March 29, 2024, https://folgerpedia.folger.edu/Garrickomania:_Garrick%27s_Image. Garrick was also the subject of numerous paintings—indeed it has been argued that he is “the most often painted Englishman”—however, it is through reproductions that his celebrity reached its zenith (Lance Bertelsen, “David Garrick and English Painting,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 11, no. 3 [Spring 1978]: 308).

[27] It was destroyed in a fire at the Stratford town hall in 1946 together with a portrait of Shakespeare that Garrick had commissioned from Benjamin Wilson. A copy is now in the collections of the National Trust at Charlecote Park, Warwickshire, inv. no. NT 533870.

[28] The prints were made by Valentine Green. See the British Museum, acc. no. 1870,0625.629, and Yale Center for British Art, acc. no. B1970.3.367, for two examples.

[29] By Nathaniel Marchant of about 1769–1773.

[30] James Tassie, A Catalogue of Impressions in Sulphur of Antique and Modern Gems from which Pastes are Made and Sold (London, 1775), no. 2822. A red sulfur copy with the same number is present in the Walters cabinet (acc. no. 42.1449). In the 1791 Raspe catalogue the same cameo is listed as no. 14200, and a slightly different version as no. 14201.

[31] Most notably, Josiah Wedgwood (British, 1730‒1795) after a cameo modeled in 1777 by William Hackwood; for one example in black basalt, see the British Museum, acc. no. 1888,0307,I.552. Wedgwood remarked that this and other cameos of Garrick were best sellers (Katherine Eufemia Farrar, Letters of Josiah Wedgwood, [Women’s Printing Society, 1903], 2: letter nos. 394, 399, 482). The Metropolitan Museum of Art includes an additional wax profile portrait of Garrick after a model by James Tassie for Josiah Wedgwood, no. 50.187.25.

[32] Tassie’s 1775 catalogue lists four cameos of Shakespeare, nos. 2816-2819, immediately followed by three of Garrick, nos. 2820-2822. The 1791 catalogue, compiled by Rudolf Erich Raspe (1736–1794), includes seventeen portraits of Garrick, nos. 14195-142010 and 15777, as well as eighteen of Shakespeare, nos. 14407-14425.

[33] See the British Museum, acc. no. 1900,0623.400, for a ca. 1780 Tassie clear glass intaglio, for one example. The link between Shakespeare and Garrick was so strong that it carried into the afterlife as well, embodied in the epitaph on Garrick’s tomb in Westminster Abbey: “Shakespeare and Garrick like twin stars shall shine / And earth irradiate with a beam divine.”

[34] Gray incorrectly identifies this as “sealing wax” (James and William Tassie, 107); throughout his text he consistently misapprehended Tassie’s materials and techniques, a shortcoming only rectified much later by John P. Smith in 1995 in his essay “The True Methods of James Tassie” in James Tassie, 21–27. Tassie may have occasionally employed sealing wax to test an impression but not to create finished artworks; an impression of an intaglio of the dying Gaul, in what seems to be red sealing wax, is present on the reverse of a trade card (acc. no. 42.1449.rel.9) located in one of the bottom drawers of his shop cabinet, now in the Walters Art Museum (acc. no. 42.1449).

[35] Surviving wax models from James Tassie’s hand are relatively rare; as Raspe noted in the introduction to the 1791 catalogue, the wax models are “liable to be defaced,” and many did not survive. Extant examples of profile portraits in relief include National Galleries of Scotland, acc. no. PG1900 (Robert Harker, 1777), and acc. no. PG1469 (Rev. George Lawson, 1794); Metropolitan Museum of Art, no. 38.145.34 (James Gregory, M.D., 1791), and no. 38.145.35 (Hugh Blair, D.D., late 18th century). Several have also been sold on the art market in recent years.

[36] Tassie, A Catalogue of Impressions, 96. This appears to refer to the gem engraver Robert Bateman Wray (British, 1715–1779). An example is present in drawer XX of the cabinet now at the Walters (acc. no. 42.1449).

[37] These included prints, such as that by Saunders described above, as well as a number of tokens and medallions, such as those by Westwood described in note 23, the enamel medallion referenced in note 24, and the cameos by Wedgwood and Tassie described in notes 31 and 32, respectively.