The great appeal of Fernand Thesmar’s transparent enamel cups, both to his contemporaries and to modern viewers, lies partly in the peculiar techniques he employed in their creation. Combining the segmented color fields of monumental Gothic stained-glass windows with the delicacy and three-dimensionality of fine goldsmith’s work,[1] the means by which Thesmar’s unsupported enamel cups were created are far from self-evident—even verging on the contradictory—leading some commenters to invoke poetic mysteries and mythical beings in their descriptions of his work.[2]

Examination of the three cups in the Walters Art Museum yields evidence of Thesmar’s techniques, and comparison provides valuable information on their evolution over a roughly fifteen-year span—from the likely creation of the two cups decorated with the names of Theodore Child (acc. no. 44.571) and W. T. Walters (acc. no. 44.572) in the late 1880s to the production of the cup with poppies (acc. no. 44.573) dated 1903.

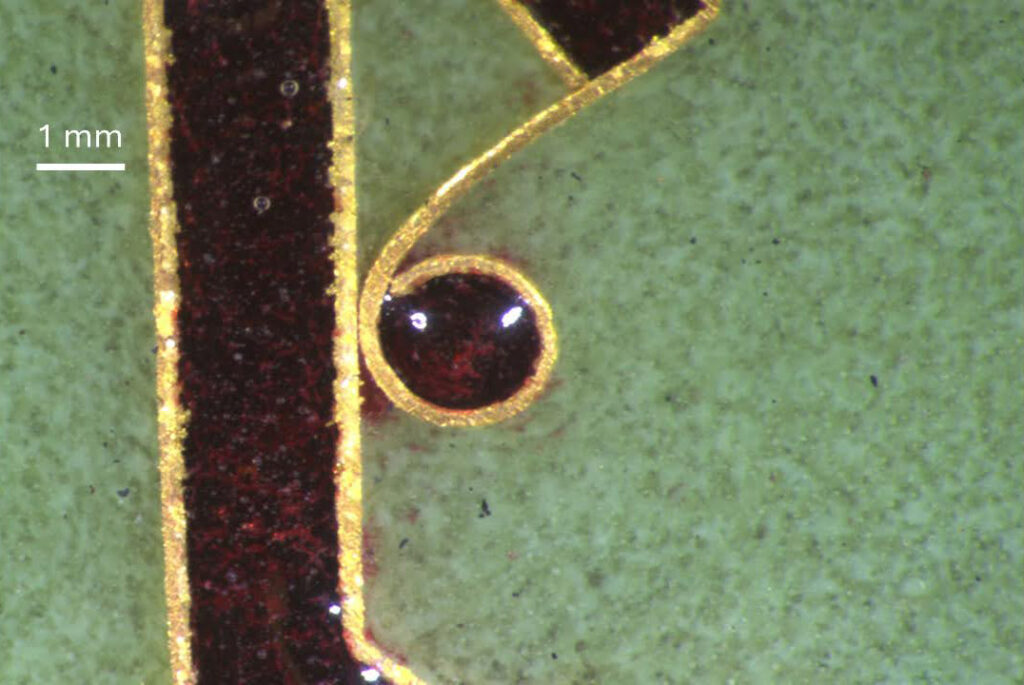

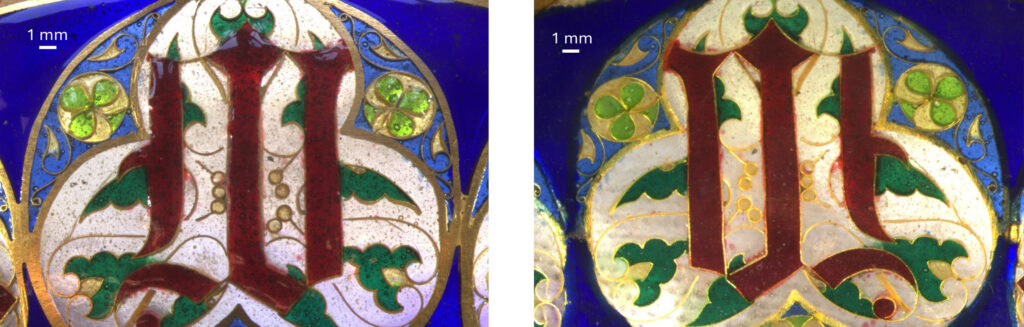

Detail of the interior. Note the flecks of gold over the slightly cloudy ground; this ground layer has flaked away from the red letter at the center of the image.

Fernand Thesmar (French, 1843‒1912), Cup, 1887‒1888, transparent enamel, gold, H: 2 3/8 × Diam: 3 7/16 in. (6 × 8.7 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by William T. Walters before 1893 (perhaps 1891?), acc. no. 44.571

Of particular interest is the cup with the name of Theodore Child. The design of this cup is unusual for a number of reasons, including its flared profile, the high pierced foot on which it rests, and its Gothic style motifs. Unusually amongst Thesmar’s oeuvre, the gold cloisons that define the letters of the name are entirely unsupported within the band of pale green translucent enamel that forms the body of the cup, appearing to float free of the goldwork at the rim and foot. Close examination of the interior shows that a thin continuous layer of transparent enamel is present overall, though in small areas of damage it has cracked or flaked away from the enamel and gold cloisons that it covers. Small flecks of gold remain embedded in this thin transparent layer on the interior. These bear no relation to the external design and are only visible under magnification (fig. 1).

These observations support the conclusion that Thesmar created his transparent enamels by applying and firing them over a metal support that was later removed—in this case, likely one of gold. In modern practice, most transparent (or “plique-à-jour”) enamel of similar size and dimensionality is created by covering a copper support with a transparent enamel ground layer to which the cloisons are affixed, and the colored enamel is slowly built up in multiple firings. The copper support is then dissolved away using an acid (such as nitric acid) that does not affect the enamel. The presence of traces of gold on the transparent enamel on the interior of the Child cup indicates that Thesmar may have employed a support of gold, rather than copper, and relied on aqua regia (a mixture of hydrochloric and nitric acids) to dissolve it away from the interior once the enamel had been applied to the exterior. Apart from the expense and difficulty of using gold as a temporary support (and presumably recovering the gold from the acid solution), this choice is somewhat precarious, as it relies on the thin transparent ground to prevent the aqua regia from dissolving the gold cloisons as well.

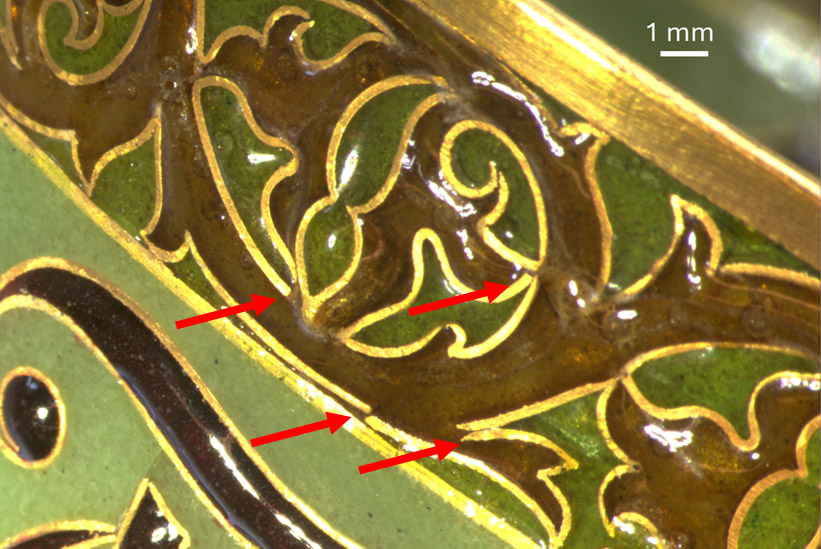

Detail of the exterior of Cup, acc. no. 44.571. Note the slightly misaligned gold cloisons along the top edge of the cup.

An 1888 article in the Baltimore American newspaper provides a clue as to why Thesmar may have chosen gold for his support;[3] reference is made to “a Parisian jeweler” who informed his experiments with the technique.[4] Perhaps the first recorded example of nineteenth-century transparent enamel was created by Auguste Louis-Hippolyte Lefournier (French, 1835‒1860) on the ribs of a fan for Eugène Fontenay in 1853; other jewelers produced isolated examples in the following two decades. Frédéric Boucheron exhibited transparent enamel at the 1867 International Exhibition and purchased a patent for the technology in 1872. There are thus several candidates for the “Parisian jeweler” with whom Thesmar consulted, any of whom would have worked primarily with gold.[5]

Detail of the exterior of Cup, acc. no. 44.571. Note the slight spillover of red enamel into the surrounding green enamel.

The gold cloisons on the Child cup are the thickest of those on the three cups in the Walters’ collection and do not all lie perfectly flush or in precise contact (fig. 2). This would suggest some difficulty in placing and securing the cloisons during their assembly. In some small areas visible under magnification, enamel from one color field spills slightly over the cloisons or into another color, most notably on the raised red letters of the name on the body, perhaps suggesting a slightly hesitant hand in the application of the enamel (fig. 3).

Detail of the exterior showing medallion with the letter W (left). Note the slight spillover of red enamel.

Detail of the interior, showing the same medallion with the letter W (right). Note that not all of the gold cloisons have been exposed during polishing, most notably those at the perimeter of the medallion.

Fernand Thesmar (French, 1843‒1912), Cup, 1887‒1888, transparent enamel, gold, H: 1 3/4 × Diam: 3 11/16 in. (4.4 × 9.3 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, William T. Walters, by commission, ca. 1887, acc. no. 44.572

The cup with the name of W. T. Walters, which may be of similar or slightly later date, is certainly related in style to the Child cup, especially in its use of Gothic style motifs that may ultimately derive from the celebrated Mérode Cup and related examples of medieval enamel. Yet the form is more typical of Thesmar’s later output: of approximately hemispherical shape, resting on a very low, undecorated foot. The cloisons are thinner, and virtually all are flush on the exterior. Some very small spillover of the enamel is present, again most notably on the raised red letters of the name. Unlike the Child cup, however, no transparent enamel or traces of gold are present on the interior. Instead, it has been mechanically polished to remove the slightly cloudy transparent ground, creating a smooth interior and enhancing the color and translucency of the enamels. Very faint, intersecting incised lines are present on the interior, apparently used as a guide in the process of polishing. Most but not all of the gold cloisons have been exposed during polishing, meaning that the design is visually similar on the interior and exterior, though the fine details of the medallions on the foot and body are not as easily discerned on the interior (fig. 4).

Fernand Thesmar (French, 1843‒1912), Cup with Poppies, 1903, translucent enamel, gold, H: 1 3/4 × Diam: 3 11/16 in. (4.4 × 9.3 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, acc. no. 44.573

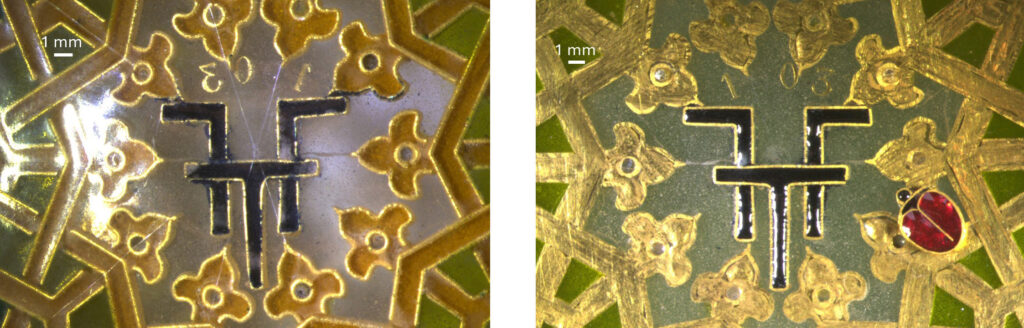

The cup with poppies, dated 1903, is the most finely worked and complex of the three (fig. 5). The cloisons are very fine and very precisely placed, and while the style is quite distinct from the Gothic-style name cups, some of the same individual cloisons shaped as keyhole-like circles and lines are employed on the centers of the poppies and on the trefoil medallions of the W. T. Walters cup. The enamel is very precisely applied and has been raised above the cloisons to suggest the dimensionality of the petals and stamens, with virtually no spillover. The interior is highly polished, with regular, intersecting incised lines evident when viewed in reflected light (fig. 6). All the gold cloisons have been exposed on the interior, making the design perfectly visible. What at first may appear to be a separately made overlay of gold basketwork at the foot is in fact a second layer of translucent yellow enamel within gold cloisons that has been gilded and burnished overall on the exterior (fig. 6). This trompe-l’oeil effect is only revealed after examining both the interior and exterior of the cup. On the edge of this trompe-l’oeil gilded basketwork, a further layer of translucent enamel has been added in the form of a small ladybug (fig. 7). (A second ladybug is also present on the underside of the foot.)

Detail of the bottom of the interior of Cup with Poppies, acc. no. 44.573, showing Thesmar’s monogram (left). Note the intersecting incised lines and yellow enamel within the cloisons.

Detail of the underside of bottom, showing Thesmar’s monogram (right). Note the burnished gold over the yellow enamel.

Detail of the exterior of Cup with Poppies, acc. no. 44.573. Note the ladybug applied over the raised gilded transparent enamel basketwork applied over the transparent enamel cup with poppies.

Taken as a group, the three cups show evidence of an evolving technique employing the use of mineral acids to remove metal supports (likely gold) to create these enamel cups, supporting Jo Briggs’s dating in her accompanying note in this volume. The Child cup, which retains traces of this process, may be viewed as at least partly experimental. The Walters cup, whose polished interior completely removes the evidence of this technique, anticipates the highly refined output of Thesmar’s later years, while the cup with poppies, though perhaps less original in its design, represents a tour de force of the technique in its use of a triple layer of translucent enamel. These three cups thus encapsulate the celebrated career of Thesmar as an enamel artist, from his redevelopment of the medieval transparent enamel technique in the late 1880s to the height of his renown in the early years of the twentieth century. Far from dispelling the mysteries of this “magician,” their close study reveals a craftsman dedicated to perfecting an exacting and unusual artform whose toil was transmuted into the glittering treasures that continue to entrance visitors today.

Acknowledgments

I wish to extend my thanks to Jo Briggs, Jennie Walters Delano Curator of 18th- and 19th-Century Art, and Earl Martin, the Deborah and Phillip English Curator of Decorative Arts, Design, and Material Culture, for sharing their research and observations on these cups. Sincere thanks are due as well to former Head of Objects Conservation Meg Craft and former Assistant Conservator Ariel O’Connor, whose 2014 examination of the cup with poppies (acc. no. 44.573) piqued my interest in this group.

[1] Indeed, the famous Mérode Cup, now in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum (acc. no. 403:1, 2-1872), which may have served as a source of inspiration for Thesmar, includes panels on the beaker and cover that resemble miniature stained-glass windows with pointed Gothic arches. See Jo Briggs’s note in this volume, “‘The Joy of Pure Enchantment, Fragile and Lasting Beauty’: Two Transparent Enamel Cups by Fernand Thesmar (1843–1912) in the Walters Art Museum.”

[2] Victor Champier, “Fernand Thesmar,” Revue des arts décoratifs 16, 1896, 381.

[3] “A Wonderful Enamel,” Baltimore American, March 15, 1888. See Briggs’s note.

[4] The early history of jewelers’ experiments with transparent enamel in Paris is the subject of a forthcoming dissertation by Manon Sauliere in fulfillment of a master of arts in History of Art applied to Collections at the École du Louvre. I am indebted to her for sharing Evelyne Possémé’s article on nineteenth-century enameled jewelry in Paris, “L’émail et la bijouterie dans la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle,” in Biennale Internationale des Arts du Feu de Limoges, ed. Paul Gineste (Musée Municipal de l’Evĉhé, 1994).

[5] It is important to note that the known early examples of transparent enamel are usually flat and generally quite small, which suggests they were created using a different technique, possibly by firing the enamel on a sheet of mica, which does not fuse to the enamel when heated.