The splendid pair of Visigothic eagle fibulae in the Walters Art Museum (acc. nos. 54.421 and 54.422) is widely known and has served as an emblem for the museum for much of its ninety-year history, appearing on stationery, publications, visitor badges, reproduction jewelry, and other products.[1] However, the museum also holds a third Visigothic eagle fibula (acc. no. 54.423), less well known and more damaged (fig. 1). It is nevertheless worthy of consideration as a rare survival of elite Iberian jewelry from the late sixth or early seventh century CE.[2] Recent study of this third fibula has shown that both the materials and techniques of manufacture differ from those employed in the more famous pair. While these three fibulae are all products of a shared visual and material culture, these differences likely indicate the third example was created at a different time and possibly a different place from the other pair.

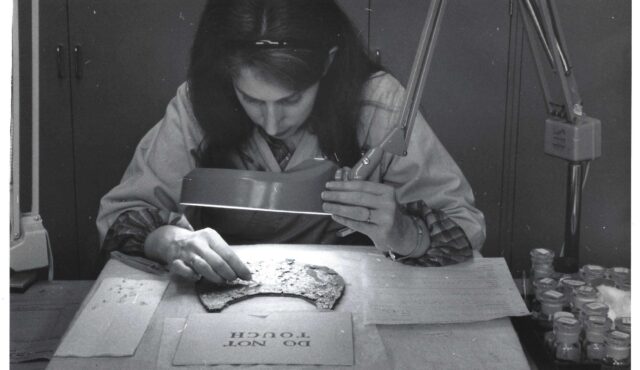

Unidentified Visigothic artist, Eagle Fibula, 6th‒early 7th century, copper alloy, gilt copper alloy, gold foil, silver foil (?), garnet, glass, cuttlefish bone and/or shell, 4 5/16 × 1 7/8 × 9/16 in. (10.9 × 4.8 × 1.4 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Acquired by Henry Walters, 1910, acc. no. 54.423, front and back

Like the more famous pair, this third example was once likely one of a pair of mirror-image eagle fibulae, intended to be worn at the shoulders to fasten a garment such as a cloak, most likely for a woman of high status.[3] The fibula was purchased by Henry Walters in 1910 from the Paris dealer Jacques Seligmann, who claimed it had been found in north central Spain.[4] It is decorated with a tessellating cloisonné design of inlaid garnets, blue glass, and two distinct opaque white materials (to which we will return later).

The body of the fibula is constructed of a number of separate pieces of copper alloy: a flat back plate, a continuous wall at the outer edge, a raised central boss, and individual cloisons (partitions) separating the inlays. Some of the cloisons are askew, and some do not join tightly, indicating that the appearance of the top (front) surface was prioritized during manufacture. There are remains of an iron pin and a broad copper-alloy catch on the reverse, showing that the fibula originally functioned in much the same way as a modern safety pin. Traces of gilding remain on the show surfaces, evidence that the copper alloy on the front and sides of the pin was originally gilded. In his introductory essay to the catalogue Arts of the Migration Period in the Walters Art Gallery (1961), “Forms and Symbols,” Phillipe Verdier asserts that the gilding of this and similar brooches was not only done in imitation of gold jewelry, but indeed “with the purpose of faking gold,”[5] though this seems speculative.

Visigothic fibulae, buckles, and other ornaments with cloisonné inlay are typically constructed of backing plates and side walls secured by rivets.[6] However, visual inspection and x-ray radiography of this fibula does not reveal the presence of rivets, pins, or other mechanical attachments within the structure (fig. 2). The back plate of the fibula is soldered to the side walls and the thinner cells of the cloisonné, as well as the separately made central boss. Likewise, the remains of the catch and attachment for the iron pin were soldered in place rather than attached mechanically. The reliance on solder for the assembly of the fibula may be unusual for this type of object, but techniques for soldering were widely employed throughout the ancient Mediterranean world and would have been available to Visigothic craftspeople of the sixth and seventh centuries CE.

X-ray radiograph of fig. 1

In areas where the inlays have been lost, a white, cementitious, putty-like material is visible within the individual cloisons. Though this material has not yet been characterized by analytical methods, it appears to have been applied as a paste before hardening and may be a lime-based mortar or similar material intended as an adhesive bedding for the foil-backed inlays.

Over this layer of white material, thin reflective white metal foils are present behind each of the garnet and blue glass inlays. Visual inspection under binocular magnification suggests that the foils are silver; there is some darkening at the edges of the foils and in areas exposed by damage, which suggests the formation of tarnish. Reflected near-infrared photography captures details of the reflective metallic foil inlays that are difficult to discern otherwise (fig. 3). The foils are slightly smaller than the inlays and have been trimmed at angles with a blade. The shapes are often quite approximate; they do not completely fill the cells in which they are placed.

Reflected near-infrared photograph of fig. 1

In addition to the garnets and blue glass, there are three inlays of opaque white material: one to the left of the central boss, one at the bottom right tail feather, and one at the bottom left tail feather. It has long been recognized that these white inlays are not all of the same material, though there has been considerable confusion as to what they may be.[7] The inlays to the left of the central boss and to the bottom right tail feather have been identified by former Walters Art Museum conservators Terry Drayman-Weisser and Meg Craft as cuttlefish bone, based on the facts that they are primarily calcium carbonate, are porous and easily marked, have a fine lamellar structure, and visually resemble known samples of cuttlefish bone. This material exhibits no visible fluorescence under long- or short-wave ultraviolet radiation.

The remaining white inlay on the bottom left tailfeather has tentatively been identified as shell in the past. It is white in color, tinged with green, and has a smooth, hard surface with a slight nacreous sheen. The inlay has an irregular concentric circular structure and exhibits a faint visible fluorescence under long- and short-wave ultraviolet radiation. All of these characteristics are shared by opercula (the “trap doors” found on most snails and some gastropods), suggesting this inlay may be a bisected operculum. It is unclear why this different material was chosen for this particular inlay, though it is possible it may be a later replacement, perhaps added during the used life of the object. The circular shape of an operculum would certainly lend itself to the semicircular cloison it fills, as it would take a minimum of effort to shape and fit it in place.

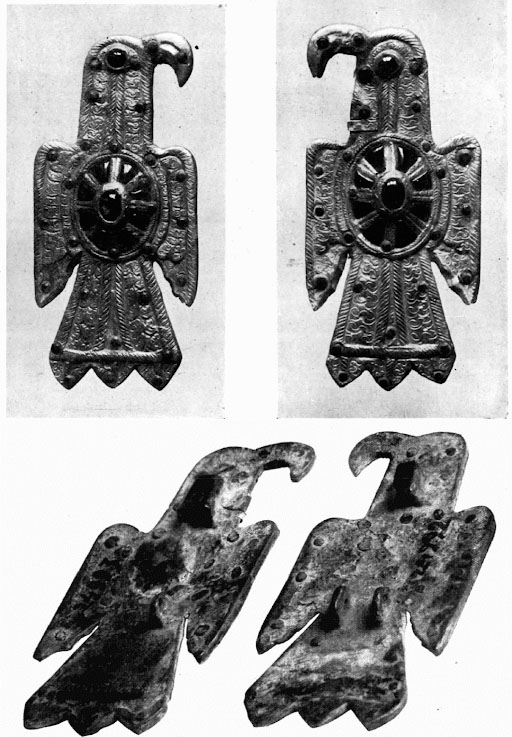

It is worth contrasting the materials and construction of this fibula with the other Walters pair (acc. nos. 54.421 and 54.422), dated slightly earlier, to the sixth century CE. That pair was purchased by Henry Walters in 1930 from the Paris dealer Henri Daguerre, who said they had been found at Tierra de Barros, Badajoz, Extremadura, in central Spain. Given the highly portable nature of fibulae such as these, the places in which they were excavated are unlikely to reflect their original locations of manufacture,[8] meaning that differences in materials and techniques are of greater significance when weighing considerations of dating and origin.

The paired eagle fibulae are each constructed of gilded copper alloy surrounds containing frameworks of gold cloisons secured to the back plates with silver rivets in a manner more typical of Visigothic inlaid fittings. The cloisons are set with blue and green glass as well as garnets; these last are backed with gold foils. The central boss on each is set with rock crystal, and the eyes are represented by amethyst inlays surrounded by bone. Both fibulae have remains of three loops at the bottom of the tailfeathers, likely for the suspension of pendants, now lost. The fibulae retain traces of iron pins and copper-alloy catches on the reverse, similar to the third example. The paired fibulae are more luxurious and varied in their materials, suggesting a different origin from the third and perhaps a distinct clientele that nevertheless shared the same visual culture and heritage.

A curious aside in Marvin Chauncey Ross’s entry for all three of the Walters eagle fibulae in Arts of the Migration Period warrants further explanation. He writes, “When Amable Carillo Pozo, who made the false Visigothic antiquities now in many European and American Museums, was shown photographs of the Walters fibulae during questioning by the police in 1941, he said at once that he had not made them.”[9]

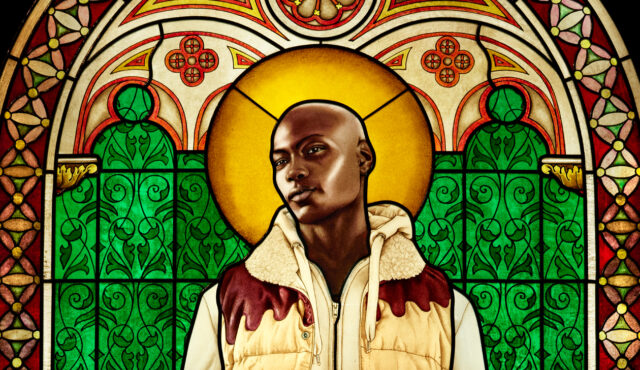

Front and back of a pair of eagle fibulae created by the forger Amable Carillo Pozo from Martín Almagro Basch, “Algunas Falsificaciones Visigodas,” Ampurias: Revista de Arqueología, Prehistoria, y Etnografía 3 (1941): 9‒10

Pozo was a forger working on the outskirts of Madrid in the 1920s and late 1930s. Pozo created buckles and brooches in Visigothic style, among them a number of eagle fibulae that he sold to the collector and scholar Don Damian Mateu, who donated them to the Museo Arqueológico de Barcelona in 1939, where they were accepted and initially published as authentic by Julio Martinez Santa Olalla (fig. 4).[10] However, experts—including Santa Olalla himself—quickly questioned the authenticity of the items. In 1941 they were sent to the Museo Arqueológico Nacional in Madrid, where they were immediately declared fakes by the director, Dr. Taracena.[11] Pozo was arrested shortly thereafter and confessed to the forgeries. Martín Almagro Basch published a description of Pozo’s known fakes that same year, in which he enumerated the historical discrepancies and anachronisms of the fakes, many of which seem to have been based on photographs of artifacts excavated at Deza in 1926 and later housed in the Museo Arqueológico Nacional.[12] Pozo’s eagle fibulae, like many of his other fakes, were lost-wax cast, rather than assembled from parts, and had nonsensical loops and pins for attachment on their reverse.[13] (Notably, the published photographs of finds from Deza showed only their front faces.)[14] Santa Olalla contacted museums with collections of Visigothic art throughout Europe and the United States to track down Pozo’s forgeries and may have played a role in contacting Ross at the Walters.

Thus cleared of any taint of inauthenticity, the third eagle fibula at the Walters Art Museum went on to be featured in eight exhibitions between 1947 and 2010, and it has occasionally appeared in the permanent galleries at the Walters as well. Though historically overshadowed by the more famous pair, this fibula is nonetheless a significant example of Visigothic craftsmanship, distinct and perhaps unusual in its materials and methods of manufacture. It is hoped that this brief note will draw greater attention to this remarkable artifact.

[1] The Visigoths were a Germanic people who migrated from central Europe to the Iberian peninsula and elsewhere in the fifth and sixth centuries CE, conquering Roman provinces and assimilating aspects of Roman culture while developing a distinct culture and society of their own.

Since 1933, this pair of eagle fibulae has been published at least fifty times, featured in thirteen special exhibitions or loans, and spent much of the intervening time on view in the permanent galleries of the Walters.

[2] I am indebted to Jessica Arista, whose 2009 examination, documentation, and treatment of this object sparked my interest and informed this brief note.

[3] Marvin Chauncey Ross, Arts of the Migration Period in the Walters Art Gallery (The Walters Art Gallery, 1961), 23.

[4] Specifically, at Herrera de Pisuerga in Palencia province.

[5] Phillipe Verdier, “Forms and Symbols,” in Ross, Arts of the Migration Period, 22‒23n78.

[6] See diagram and discussion on page 10 of Treasures of the Dark Ages in Europe (Ariadne Galleries, 1991).

[7] The 1930s accession record for this object describes the material as “white paste” and notes that one “is modern”; in later years, the white materials have been described variously in museum records as “shell,” “mother of pearl,” or, improbably, “meerschaum.”

[8] Thriving networks of trade in the sixth and seventh centuries CE connected Italy, Iberia, and the Frankish kingdoms with the wider Mediterranean world and points east. Notably, a pair of sixth-century CE earrings at the Walters (acc. nos. 57.560 and 57.561), said to have been found in north central Spain (possibly in the same location as the pair of eagle fibulae), is believed to have been imported from Constantinople, or possibly Olbia on the Black Sea (Ross, Arts of the Migration Period, 23), though it has also been proposed that they are Iberian Visigothic products inspired by imported Byzantine jewelry (Walters Art Gallery, Objects of Adornment: Five Thousand Years of Jewelry from the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore [American Federation of Arts, 1984], 100).

[9] Ross, Arts of the Migration Period, 100.

[10] Julio Martinez Santa Olalla, “Nuevas Fibulas Aquiliformes Hispanovisigodas,” Archivo Español de Arqueología 14 (1940‒1941): 33‒54.

[11] Julio Martinez Santa Olalla, “Joyas Visigodas Falsas en el Museo Arqueológico de Barcelona,” Atlantis: Actas y Memorias de la Sociedad Española de Antropología, Etnografía, y Prehistoria y Museo Etnológico Nacional XVI (1941): 192‒93; Martín Almagro Basch, “Algunas Falsificaciones Visigodas,” Ampurias: Revista de Arqueología, Prehistoria, y Etnografía 3 (1941): 3‒14.

[12] Almagro Basch, “Algunas Falsificaciones Visigodas.”

[13] Almagro Basch, “Algunas Falsificaciones Visigodas.”

[14] These finds were published in Blas Taracena Aguirre, “Excavaciones en las provincias de Soria y Logroño,” Memorias de la Junta Superior de Excavaciones y Antigüedades, vol. 86 (1927) and Hans Zeiss, Die Grabfunde aus dem spanischen Westgotenreich (W. de Gruyter, 1934).