In the half decade before he took his own life, French artist Léon Bonvin (1834–1866) created a group of startlingly original watercolors. However, little textual documentation has been located that illuminates his work despite extensive new research undertaken for the forthcoming catalogue raisonné, Léon Bonvin (1834–1866), Drawn to the Everyday.[1] This essay therefore uses visual analysis and circumstantial evidence to piece together the context within which Bonvin’s watercolors, in particular his landscapes with middle ground figures, were conceived. Although the artist’s contemporaries describe Bonvin as a self-taught, isolated genius—a romantic story that has proved surprisingly enduring—uncovering visual sources that appear to have influenced him undermines this narrative. Indeed, they reveal further connections between Bonvin and artistic life in Paris despite the artist’s challenging economic circumstances, which necessitated he work at his family’s inn in Vaugirard, just outside Paris, and barred him from any official exhibitions or recognition during his short life.

As art historian and catalogue raisonné author Gabriel Weisberg has previously asserted, Bonvin’s much older half-brother, the painter and printmaker François Bonvin (1817–1887), was a guide for Léon; their kitchen still lifes show clear similarities, suggesting a shared interest in the work of Jean-Siméon Chardin (1699–1779), an artist who was viewed with renewed appreciation in mid-nineteenth century France.[2] In previously published research I suggest that Bonvin’s floral still lifes were shaped by his training at the École Gratuite de Dessin in Paris (also known as the Petite École), and noted similarities between his landscapes with foreground plants and the painted reserves of Sèvres porcelain.[3] In this note I aim to shed light on a further subset of Bonvin’s watercolors: his landscapes with middle ground figures.

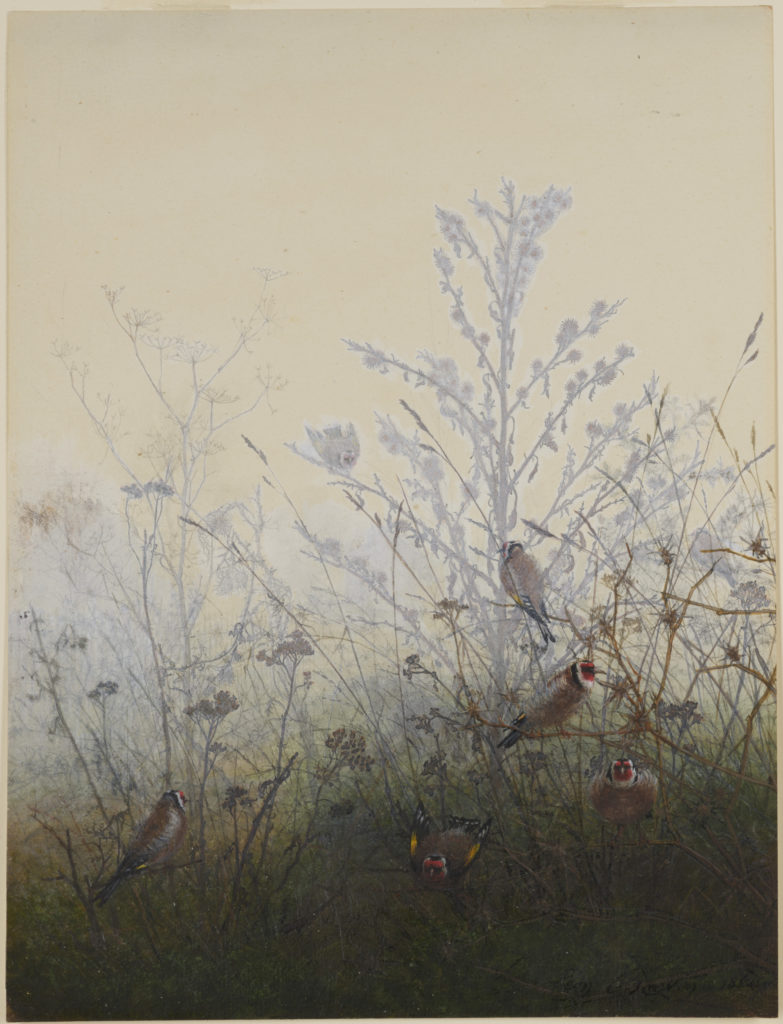

Léon Bonvin, Feverfew in front of a Landscape, Issy-les-Moulineaux (?), 1863, watercolor, gouache, iron gall ink and pen heightened with gum varnish over graphite underdrawing on moderately textured, moderately thick, cream wove paper. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, commissioned by William T. Walters, 1863 (?), certainly acquired before 1885, acc. no. 37.1518

Sixteen out of the fifty-six watercolors at the Walters Art Museum, the largest collection of Bonvin’s work anywhere in the world, are landscapes with middle ground figures, meaning this compositional format represents a significant portion of his output.[4] Watercolors in this group depict a plant in the foreground, close to the picture plane and seen from a low vantage point. Careful looking reveals diminutive figures in the middle ground, walking, sitting, boating, or working on the land. Often, buildings appear in the far distance, on or near the horizon. Examples of watercolors using this scheme include Feverfew in front of a Landscape, Issy-les-Moulineaux (?) from 1863 (fig. 1) and Thistle in front of a Winter Landscape of 1864 (fig. 2). This striking compositional arrangement recalls Japanese prints, which were so exciting artists and critics in Paris in this decade. Furthermore, links between Bonvin and French artists involved in the revival of etching in the middle of the century suggest the means by which he may have encountered these sources.[5] Indeed, I will argue that Bonvin’s watercolors also show similarities with contemporary etchings, despite the difference in media.

Léon Bonvin, Thistle in front of a Winter Landscape, 1864, watercolor with gum heightening, gouache, iron gall ink and pen, and graphite over graphite underdrawing on slightly textured, moderately thick, cream wove paper. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, acquired by William T. Walters, 1864 (?), acc. no. 37.1519

A crucial document that helps plot Bonvin’s artistic network is the catalog for an auction held at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris shortly after the artist’s death, in order to raise money for his widow and two children—it seems likely that those who contributed work knew the artist, perhaps through visits to his family’s inn which was popular with artists.[6]Twenty-two of the eighty artists listed in the sale were members of the Société des Aquafortistes (Society of Etchers), founded four years earlier, in 1862. These include Félix Bracquemond (1833–1914), Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875), Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), Charles François Daubigny (1817–1878), Maxime Lalanne (1827–1886), Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904), Johan Barthold Jongkind (1819–1891), and Théodule Ribot (1823–1891).[7] François Bonvin also was a member of the Société des Aquafortistes and practiced etching sporadically.[8] In addition, another of Bonvin’s Parisian contacts, the publisher and dealer Alfred Cadart (1828–1875), who sold his watercolors, also played a key role in promoting and supporting the etching revival.[9]

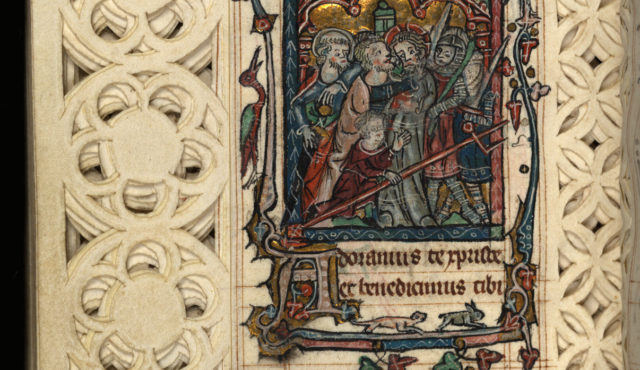

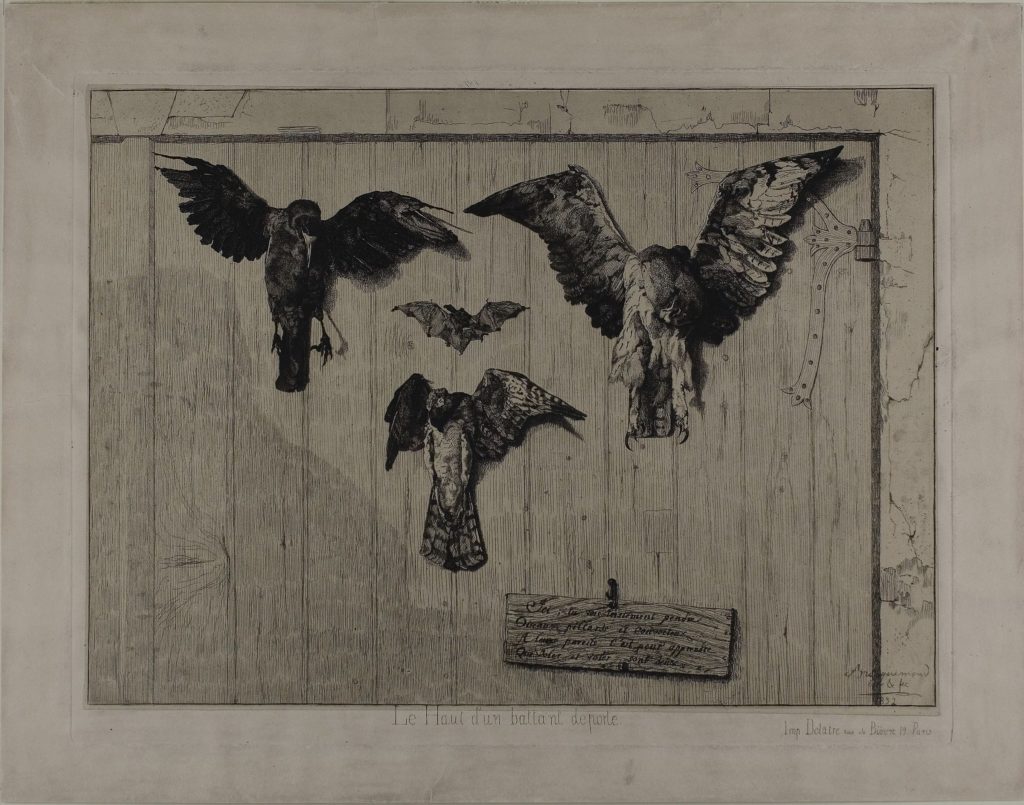

Félix Bracquemond, The Upper Part of a Door, 1852, etching and drypoint on off-white laid paper, laid down on ivory wove paper. The Art Institute of Chicago, estate of Robert Forsyth, acc. no. 1927.1728

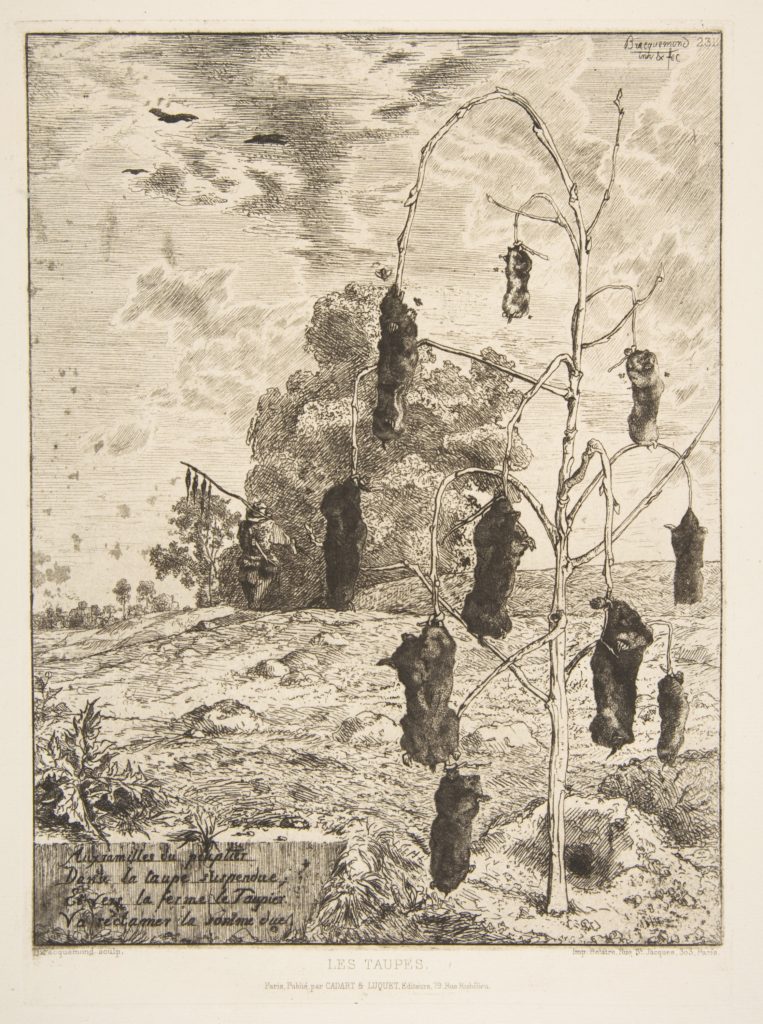

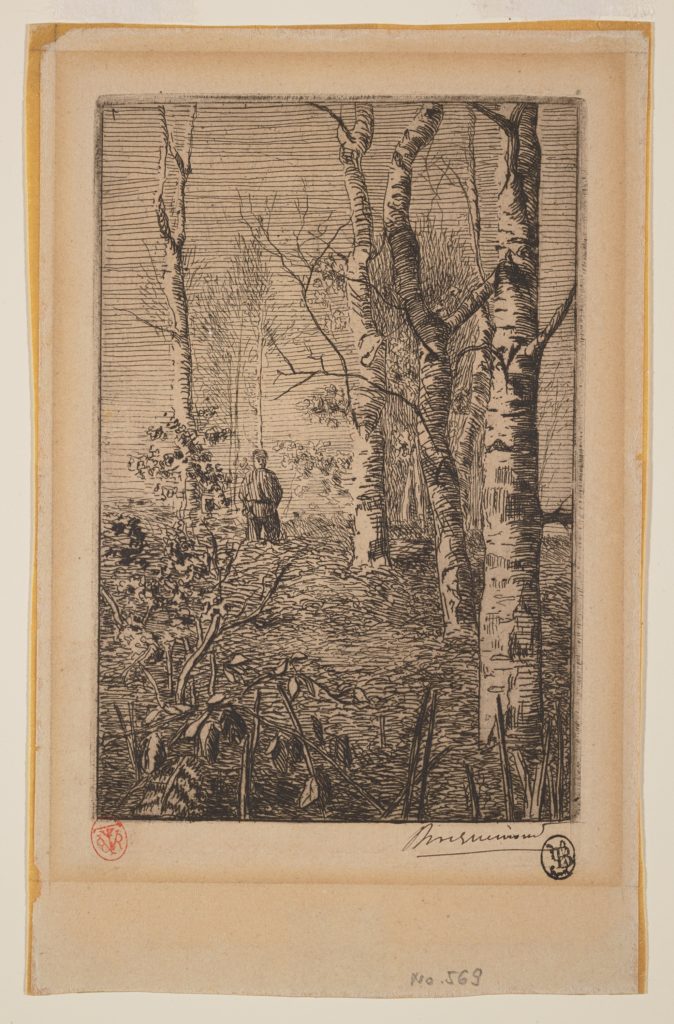

Bonvin’s landscapes with middle ground figures bear a particular resemblance to etchings by Bracquemond, who is known to have visited the Bonvin family inn.[10] Bonvin and Bracquemond both experimented with unusual compositions. For example, Bracquemond created a macabre still life of dead birds and a bat nailed by their wings to a barn door, which, forming the entire background and picture plane, pushes the dead animals into the viewer’s space (fig. 3). Bonvin’s interest in unusual vantage points is most clearly seen in his landscapes; as described previously, often the view is from ground level, as if the artist were sitting or lying among the grass and weeds. Weisberg has noted similarities between Bracquemond’s etchings and Bonvin’s watercolor Goldfinches, dated 1864 (fig. 4). Specifically, this watercolor recalls Bracquemond’s Sarcelles (Teals) and Perdrix (Partridges) from 1853, L’étang (The Pond) from about 1855–1860, and Un rappel (A Reminiscence) from 1859. These prints, and others by Bracquemond, depict birds from a low angle, sometimes with a landscape vista beyond. Bonvin’s decision to show finches perching in weeds in the foreground of Birds Resting on Bushes may reflect a knowledge of these works, as well as Bracquemond’s etching of 1854 Les taupes (Moles), in which ten dead moles are strung from a sapling close to the picture plane (fig. 5). The moles’ executioner, carrying a pole strung with dead rats, is seen in the middle distance, walking away from the viewer. Compositionally, this prefigures the inclusion of people working in the middle ground of Bonvin’s landscapes. More particularly, Bonvin’s watercolors where these figures are almost completely subsumed in the landscape, such as Gray Mullein in the Undergrowth (fig. 6) or Lane beside a Building (fig. 7), have similar compositional formats to Bracquemond’s etchings Les trois bouleaux (Three Birch Trees) of 1853 (fig. 8) or Les saules (The Willows) of about 1854–1855.[11]

Léon Bonvin, Goldfinches, 1864, watercolor with gum heightening, gouache, iron gall ink and pen, and graphite over graphite underdrawing on slightly textured, moderately thick, cream wove paper. The Walters Art Museum Baltimore, acquired by William T. Walters, 1864 (?), certainly before 1885, acc. no. 37.1517

Artist: Félix Bracquemond (French, Paris 1833–1914 Sèvres), Printer: Auguste Delâtre (French, Paris 1822–1907 Paris), Publisher: Cadart & Luquet (French, active 1863–67), Les Taupes, 1854, etching; sixth state of seven. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha, Whittelsey Fund, 1963, acc. no. 63.625.14

Léon Bonvin, Gray Mullein in the Undergrowth, 1865, watercolor with gum heightening, gouache, iron gall ink and pen, over graphite underdrawing on slightly textured, moderately thick, cream wove paper. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, acquired by William T. Walters, acc. no. 37.1509

Léon Bonvin, Lane beside a Building, 1865, watercolor with gum heightening, gouache details, iron gall ink and pen over graphite underdrawing on slightly textured, moderately thick, cream wove paper. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, acquired by William T. Walters, before 1885, acc. no. 37.1645

Félix Bracquemond, Three Birch Trees, with a Child, 1853, etching. The Minneapolis Institue of Art, gift of Gabriel P. and Yvonne M.L. Weisberg for the Weisberg Collection of European Drawings and Prints of the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, acc. no. 2014.127.4

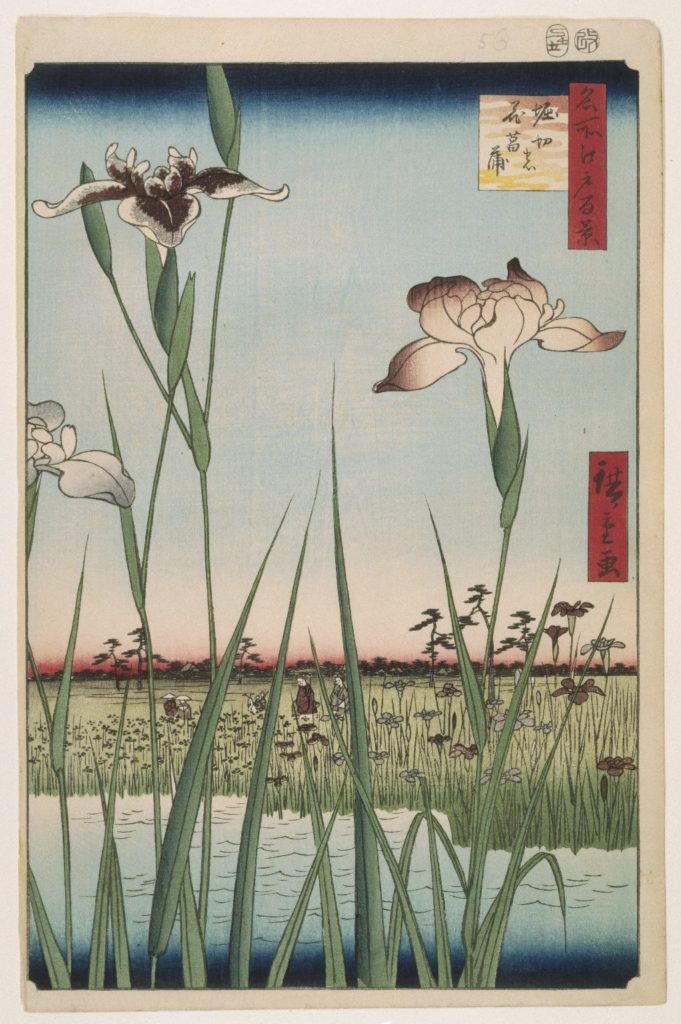

Utagawa Hiroshige (Ando), Horikiri Iris Garden (Horikiri no Hanashobu), no. 64 from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857, woodblock print. Brooklyn Museum, gift of Anna Ferris, acc. no. 30.1478.64

From the late 1850s, Bracquemond’s etchings are generally considered to have been influenced by Japanese prints.[12] In 1858 trade between Japan and France officially recommenced after two centuries of Japan’s sakoku (locked country) policy, with a treaty that opened diplomatic relations. However, before this date Japanese prints had entered European public collections, and reproductions of these artworks were published in books and articles on Japan, as they continued to be after trade recommenced.[13] By 1861, Edmond (1822–1896) and Jules de Goncourt (1830–1870) were purchasing prints by Japanese artists at the Parisian shops La Porte chinoise at 36, rue Vivienne and the Desoye family’s shop at 220, rue de Rivoli, where Madame Desoye was an authority on the subject.[14] In particular, Katsushika Hokusai’s (1760–1849) Manga, published from 1814, and Ando Hiroshige’s (1797–1858) One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, published from 1856 onwards, seem to have circulated most widely and were most frequently referenced by artists in the 1860s.[15]

Léon Bonvin, Campanula in front of a Landscape, 1863, watercolor with gum heightening, iron gall ink and pen, on heavily textured, thick, cream wove paper. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, commissioned by William T. Walters, 1863 (?), acc. no. 37.1521

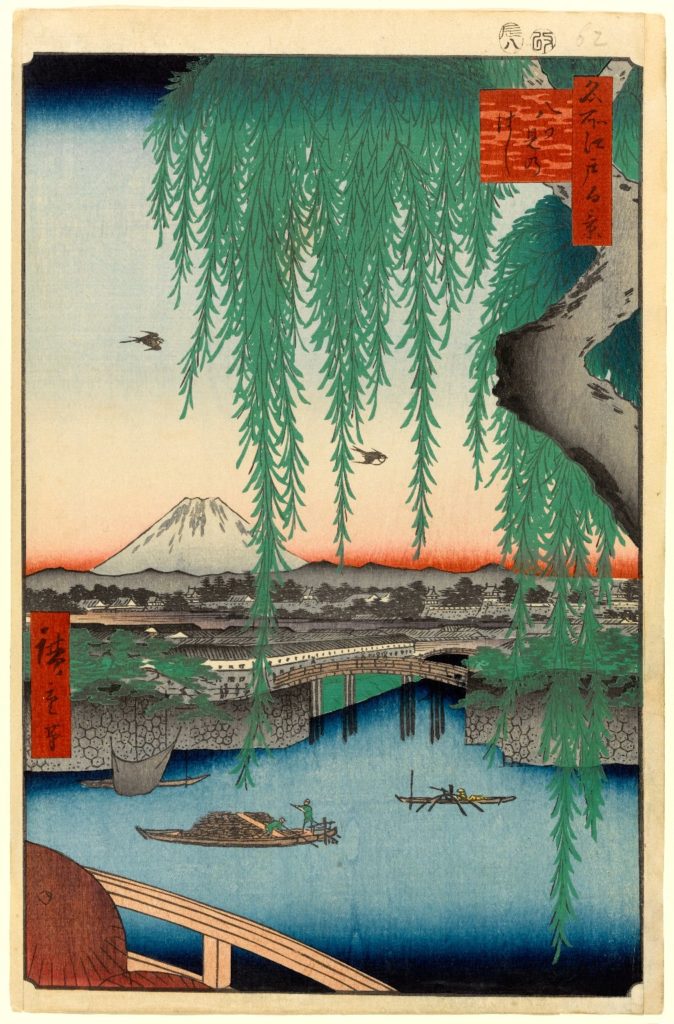

Utagawa Hiroshige (Ando), Yatsumi Bridge, no. 45 from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 8th month of 1856, woodblock print. Brooklyn Museum, gift of Anna Ferris, acc. no. 30.1478.45

A work like Hiroshige’s Horikiri no hanashōbu (Horikiri Iris Garden) from 1857 may have influenced Bonvin (fig. 9). In this print, three iris flowers, buds, stems, and leaves form a screen close to the picture plane, small figures appear in the middle distance, and buildings and trees are suggested on the horizon. The composition is strikingly similar to watercolors by Bonvin such as Feverfew in front of a Landscape, Issy-les-Moulineaux (?) (fig. 1), Thistle in front of a Winter Landscape (fig. 2), and Campanula in front of a Landscape (fig. 10), all dated 1863, where plants are isolated in the foreground against a landscape background and figures appear in the middle ground. Tree branches also sometimes screen a distant scene in both Hiroshige’s prints and Bonvin’s landscapes with middle ground figures. One print by Hiroshige, Yatsumi no hashi (Yatsumi Bridge) from 1856, shows a view of a river with boats, a townscape, and Mount Fuji seen from behind hanging willow branches (fig. 11). The same layering of tree branches and boats can be seen in Bonvin’s Willow Tree and Convolvulus in front of a River (fig. 12) and River Landscape with a Fisherman (fig. 13), both from 1865. The boats in the latter recall the way similar vessels are depicted in Hiroshige’s prints, although in River Landscape with a Fisherman Bonvin includes two butterflies replacing the birds seen in Hiroshige’s Yatsumi Bridge.[16] These close similarities suggest that Bonvin was not just aware of Japanese prints, but studied them carefully. I would speculate that Bracquemond, or one of the other artists who gathered at the inn where Bonvin worked, exposed him to these sources that were inspiring French artists and critics at the time.

Léon Bonvin, Willow Tree and Convolvulus in front of a River, 1865, watercolor with gum heightening, gouache details, iron gall ink and pen, on moderately textured, moderately thick, cream wove paper. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, acquired by William T. Walters, acc. no. 37.1654

Léon Bonvin, River Landscape with a Fisherman, 1865, watercolor with gum heightening, gouache details, iron gall ink and pen on paper. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, acquired by William T. Walters, acc. no. 37.1648

Beyond this shared interest, I want to propose a subtler resonance between Bonvin’s watercolors and etchings by his French contemporaries. In recent years, two exhibition catalogs, The Darker Side of Light: Arts of Privacy, 1850–1900 (National Gallery of Art, 2009) and The “Writing” of Modern Life: The Etching Revival in France, Britain, and the U.S., 1850–1940 (Smart Museum of Art, 2008), have grappled with the medium of etching, attempting to define its unique qualities.[17] The authors note the “quiet rhetoric” of etchings, which results from their typically small scale and the fact that they are not often exhibited, but rather stored in albums or portfolios, adding to their aura of privacy and introspection.[18] Bonvin’s watercolors share these qualities, and William T. Walters initially presented his large collection in a specially commissioned leather-bound album, mediating how they were viewed.[19] Peter Parshall asserts in The Darker Side of Light that collectors of etchings exhibit a “fetishistic pursuit of rarity, and a temptation to achieve completeness in a chosen category.”[20] This was certainly true of William Walters in his acquisition of Bonvin’s watercolors during the artist’s lifetime, and his decades-long pursuit of them following the artist’s death.[21] This persistence bore fruit: today, the majority of Bonvin’s work can be found at the Walters Art Museum, founded by William’s son, Henry.

In terms of contemporary reception, romantic myths grew up around both etchers and Bonvin. Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), Champfleury (1821–1889), Philippe Burty (1830–1890), and others mythologized the etcher as working alone and in poverty, suffering and experimenting.[22] This was the image that some of the same writers promoted of Bonvin following his suicide. Certainly, Bonvin’s biography has much in common with that of the etcher Charles Meryon (1821–1868), who, after a career as a sailor, became an etcher, lived in straitened circumstances, and died in an asylum while still in his thirties. Bonvin died by his own hand at a similar age two years prior. Just as Bonvin worked almost exclusively in watercolor, Meryon was exclusively an etcher, and the audience for their art during their lifetimes was small.[23] Although they worked in different media, their output is characterized by individualistic approaches to nature depicted from unusual perspectives and viewpoints, combined with a sharp attention to detail resulting from careful observation. Bonvin’s contemporaries may have preferred the myth of an isolated genius cut off before his prime, but research shows that he was not working in a vacuum.[24] Indeed, although Bonvin’s duties as an innkeeper curtailed his artistic practice, and were perhaps burdensome, they also brought him into contact with the latest passions of the Parisian art world—etching and Japanese prints—with significant results for his artistic development.

This note is respectfully dedicated to Ger Luijten (1956–2022), champion of Léon Bonvin and director of the Fondation Custodia.

[1] Léon Bonvin (1834–1866), Drawn to the Everyday (Paris: Fondation Custodia, 2022), forthcoming at the time of writing, is the first catalogue raisonné of the artist’s work. Its publication coincides with a monographic exhibition at the Fondation Custodia in Paris, to which the Walters Art Museum is the major lender.

[2] See Gabriel Weisberg, biographical essay, forthcoming, Léon Bonvin (1834–1866), Drawn to the Everyday. For the influence of Chardin, see John W. McCoubrey, “The Revival of Chardin in French Still-Life Painting, 1850–1870,” Art Bulletin 46, no. 1 (March 1964): 39–53. For another example of the similarities between their work, compare Léon Bonvin’s watercolor Still Life with Fish, 1864 (Walters Art Museum, acc. no. 37.1526) and François Bonvin’s oil painting Still Life with Eggs, 1855, reproduced in Weisberg, Bonvin, trans. André Watteau (Paris: Editions Geoffroy-Dechaume, 1979), 50 and 211. There are also strong affinities between their drawings, particularly in their use of crayon and charcoal.

[3] Jo Briggs, “Condemned to Sparkle: The Reception, Presentation and Production of Léon Bonvin’s Floral Still Lifes,” Oxford Art Journal 38, no. 2 (March 2015): 247–63; Jo Briggs, “Landscape with Flowers: Léon Bonvin’s Watercolors and Sèvres Porcelain,” Master Drawings 55, no. 2 (Summer 2017): 195–98. After publishing the latter article in 2017, I learned that François Bonvin lived at Sèvres in the 1860s. See Weisberg, Bonvin, 72. Bonvin’s attendance at the École de Dessin is asserted in a letter dated 1884 from François to the art critic Philippe Burty. At this time Burty was gathering information for an article on Léon, commissioned by William T. Walters.

[4] To give some context for this number, other common compositions are floral still lifes and kitchen still lifes, of which the Walters’ collection contains twenty and thirteen, respectively.

[5] For an overview of the etching revival in France and an explanation of how etchings are made, see: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/etre/hd_etre.htm.

[6] See Vente au profit des orphelins de Léon Bonvin, artiste peintre. Tableaux, aquarelles, bronzes et objets divers, sale Hôtel Drouot, Paris, May 24, 1866.

[7] For a list of members of the Société des Aquafortistes in 1864, see Jean Bailly-Herzberg, L’eau-forte de peintre au dix-neuvième siècle: La Société des Aquafortistes, 1862–1867, Vol. 1 (Paris: Leonce Laget, 1972), 132.

[8] For François Bonvin’s etchings, see Weisberg, Bonvin, 308–13.

[9] See Lillian M. C. Randall, ed., The Diary of George A. Lucas: An American Art Agent in Paris, 1857–1909, Vol. 2 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979), 214.

[10] Lucien Lambeau, Histoire des Communes annexées à Paris en 1859 publiée sous les auspices du Conseil general: Vaugirard (Paris: Ernest Leroux,1912), 383.

[11] All these etchings are reproduced in Jean-Paul Bouillon, Félix Bracquemond: Le realism absolu, oeuvre gravé 1849–1859, catalogue raisonné (Geneva: Albert Skira, 1987). Around 1860, Bonvin created a panoramic watercolor now in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, which is unique in his oeuvre. Although the panorama was a popular form of entertainment, and the format was not uncommon in nineteenth-century wood engraving, it is interesting to note that in 1856 Charles Meryon made an etched panorama of San Francisco after five daguerreotypes.

[12] See Jean-Paul Bouillon, “Remarques sur le Japonisme de Bracquemond,” n Society for the Study of Japonisme, ed., Japonisme in Art: An international Symposium (Tokyo: Committee for the Year 2001 and Kodansha International, 1980), 83–108, at 84, and Deborah Johnson, “Japanese Prints in Europe before 1840,” Burlington Magazine 124, no. 951 (June 1982): 343–48.

[13] For a detailed chronology of these developments, see Le Japonisme (Paris: Ministère de la culture et de la communication, Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1988), 60–123, esp. 62–72.

[14] Le Japonisme, 72. For Madame Desoye’s important place in the dissemination of knowledge about Japanese art see Elizabeth Emery, Reframing Japonisme: Women and the Asian Art Market in Nineteenth-Century France (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020).

[15] See Hendrik Budde, “Japanische Farbholzschnitte und Europäishe Kunst: Maler und Sammler im 19. Jahrhundert,” in Doris Croissant, Lothar Ledderose et al., eds., Japan und Europa, 1543–1929 (Berlin: Berliner Festspiele, Argon, 1993), 164–77.

[16] It is also possible that Hiroshige’s night and dawn views may have influenced Bonvin’s scenes set at similar times of day. There are fewer parallels between Hokusai’s prints and Bonvin’s watercolors; however, Hokusai’s depiction of asagoa (morning glories), where stems, leaves, and flowers cross and fill the picture plane, could be compared to Crab Apple Blossom, 1863 (Walters Art Museum, acc. no. 37.1507). Here, blossoms and leaves across a trellis fill page.

[17] Peter Parshall et al., The Darker Side of Light: Arts of Privacy, 1850–1900 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2009); and Elizabeth Helsinger et al., The “Writing” of Modern Life: The Etching Revival in France, Britain, and the U.S., 1850–1940 (Chicago: Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, 2008).

[18] Helsinger et al., The “Writing” of Modern Life, 2; and Parshall et al., The Darker Side of Light, 14, 15.

[19] As with other subsets of his collection of works on paper, Walters stored watercolors by Bonvin in a specially commissioned album with bespoke watercolors introducing and concluding the volume by Jean-Marie Reignier (1815–1886) (Walters Art Museum, acc. nos. 37.1501 and 37.1531). From late 1885 or early 1886, following the publication of Burty’s article on Bonvin in the Christmas edition of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine for 1885, thirteen watercolors were put on display in Walters’s townhouse.

[20] Parshall, The Darker Side of Light, 27.

[21] Although the date at which Walters purchased many of his watercolors by Bonvin is not known or can only be conjectured, about half appear to have been acquired during the artist’s lifetime.

[22] See Anna Arnar, “Seduced by the Etcher’s Needle: French Writers and the Graphic Arts in Nineteenth-Century France,” in Helsinger et al., The “Writing” of Modern Life, 39–55.

[23] See James D. Burke, Charles Meryon: Prints and Drawings (New Haven, CT: Yale University Art Gallery, 1974).

[24] There is a striking similarity between some of Bonvin’s watercolors and pastels by Jean-François Millet (1814–1875) created in the few years after Bonvin’s death. See for example Dandelions (1867–68) and Farmyard by Moonlight (1868), both in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Les narcisses et les violettes (ca. 1867) in the Kunsthalle, Hamburg.