About this Volume

A Wonder at the Walters: Essays in Honor of Joaneath Spicer

Joaneath Spicer once said she was born on the third floor of the Walters Art Museum. In point of fact, she first came to the museum just over thirty years ago as the James A. Murnaghan Curator of Renaissance and Baroque Art, and since that time has made an indelible mark on the institution. A prolific writer, lecturer, and mentor, Joaneath’s contributions as a scholar, curator, and colleague extend well beyond the walls of the museum and art history. Joaneath has expanded scholarship in Renaissance and Baroque art as well as brought the arts of antiquity, of the contemporary world, and even zoology and taxidermy firmly into conversation with the works she stewards. Yet, perhaps Joaneath has correctly ascribed the place of her “birth,” as the art, people, and spaces at the Walters Art Museum have directly contributed to who she is today (fig. 1). In celebration of her over thirty-year career at the Walters, this volume of the Journal of the Walters Art Museum is dedicated to Joaneath Spicer and her incredibly wide-ranging scholarly and curatorial interests.

Joaneath in the Chamber of Wonders. Photo by Pam Betts

Joaneath began her scholarly career studying the drawings of Dutch artist Roelandt Savery (1576–1639),[1] a topic that has threaded throughout the tapestry of her scholarship. From her first article onward, she has focused not only on the artist, who worked for a time in the court of Rudolf II, but also on diverse early modern paintings and drawings, including making important artist attributions. Her first major exhibition, Masters of Light: Dutch Painters in Utrecht During the Golden Age (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Walters Art Museum, and the National Gallery, London, 1997–1998), highlighted her deep knowledge of Dutch painters. But as a true “Renaissance woman,” her scholarly and curatorial work has gone far beyond the realm of painting. More unusual and introspective offerings have included a breakdown of painted postures in “The Renaissance Elbow,”[2] a deeply personal discussion of femininity and authenticity through the lens of the restoration of damaged artworks in “Criteria for Breast Reconstruction Surgery,”[3] and an exhibition bringing together art and science, Touch and the Enjoyment of Sculpture: Exploring the Appeal of Renaissance Statuettes (2012), in collaboration with neuroscientist Dr. Steven Hsiao. An inflection point in Joaneath’s career was the reinstallation of the Renaissance and Baroque art at the Walters, which included the iconic Chamber of Wonders—the first such installation in a US museum. This project, as well as other temporary shows that she worked on, fed into her meditations on the nature of exhibitions.[4] Presciently, years before the Walters Art Museum shared in its 2015 Strategic Plan the desire to “situate itself more firmly in Baltimore—a diverse city that is majority African American,” Joaneath was publishing on representations of people of African descent in Renaissance Europe[5] and in the last several years has made magnificent strides toward diversifying who is represented in the collections she stewards at the Walters.[6] With a view to the present and future, Joaneath’s first exhibition at the Walters, Going for Baroque: 18 Contemporary Artists Fascinated with the Baroque and Rococo (1995), as well as her most recent, Activating the Renaissance (2022–2023), brought contemporary artists into dialogue with historic ones represented in the Walters collection, emphasizing the continuing influence and importance of the past on the present and future.

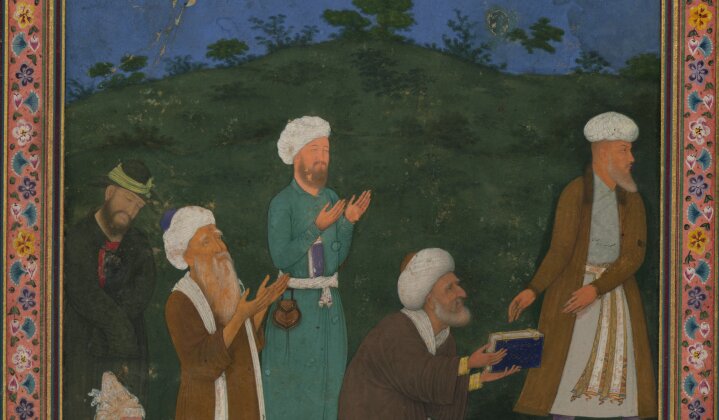

The essays included in this volume of the Journal of the Walters Art Museum speak to many of the aforementioned themes of Joaneath’s career. We begin with an introspective interview of Joaneath by Dr. Leslie King Hammond, Professor Emerita and founding Director of the Center of Race and Culture at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). Dr. King-Hammond seeks to find out the experiences that have turned Joaneath’s focus to publications, projects, and purchases that have brought much needed attention to representations of Africans in Renaissance and Baroque art. Joaneath’s focus on bringing more diverse images to the galleries through acquisitions recently included securing a multi-year loan of a remarkable work in the collection of the Antwerp Rubenshuis, an oil painting by Jacob Jordaens, Moses and His Ethiopian Wife, ca. 1650 (fig. 2), which is currently installed in the 17th-Century Dutch Cabinet Rooms.

Jacob Jordaens the elder (Flemish, 1593‒1678), Moses and His Ethiopian Wife, ca. 1650, oil on canvas, 45 11/16 × 40 15/16 in. (116 × 104 cm). Rubenshuis, Antwerp, acc. no. S 095

Dr. Christopher Daly, who recently received his PhD in the history of art at Johns Hopkins University and is the 2021‒2024 David E. Finley Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, National Gallery of Art, was the Robert and Nancy Hall Curatorial Fellow at the Walters in 2018‒2019, working closely with Joaneath. Here he publishes his research on a monumental tondo by the Master of the Fiesole Epiphany, which he worked on during his time at the Walters. Daly not only highlights the tondo’s importance as a rare addition to the slim corpus of monumental tondi depicting a sacra conversazione, but also considers the full body of work attributed to the artist, reattributing a group of paintings to a newly named artist, the Master of 1493. In illuminating a little-known artist and type of object, Daly’s essay follows on Joaneath’s example of rediscovering important works of art in Walters’ storage[7] and of further artist reattributions, such as her multi-year research into the monumental series of 15th-century Italian panel paintings owned by the Walters celebrated in the installation Paintings for a Venetian Palace and volume 74 of the Journal of the Walters Art Museum.[8]

Dr. Judith W. Mann, Senior Curator of European Art to 1800 at the Saint Louis Art Museum, offers a meditation on how still lifes painted on lithic supports redefine the relationship between the fiction of the painted image and the material world in which they exist. Starting with the Paintings on Stone: Science and the Sacred 1530–1800 exhibition that she curated in 2022, Mann contemplates how the use of stone supports “changes everything” in relation to the meaning of the painting on it. This offering speaks directly to many aspects of Joaneath’s output—not only exhibitions and installations, but also important purchases of artwork to expand the collection, and the ways in which a single artwork can spark not only an entire installation but also further questions worthy of pursuing.

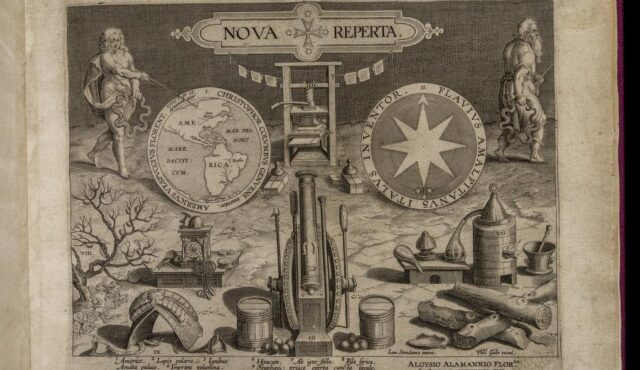

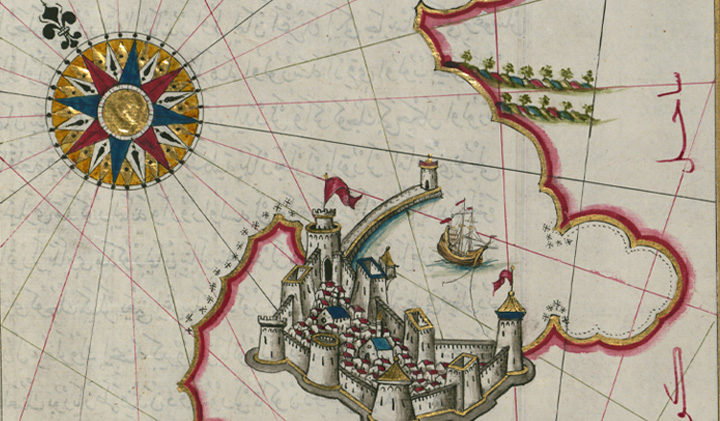

Dr. Pamela H. Smith, the Seth Low Professor of History at Columbia University and Founding Director of the Center for Science and Society, takes as her starting point Joaneath’s essay “The Role of Art and Science at the Court of Rudolf II in Prague”[9] and revisits concepts of invention and creation in the making of Kunstkammer objects of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Professor Smith additionally highlights moments of whimsy in the early modern period, especially book titles, and also the animal taxidermy that is important to the Chamber[10] as well as to the inventive, ingenious, and curious practitioners in the past.

In the fifth of our invited essays, the artist, writer, and naturalist James Prosek writes about his own interest in nature and the need to order it, exploring the ways in which Joaneath’s installation of the Chamber of Wonders at the Walters implodes orderly boundaries between art and artifact and opens the viewer’s perception. Like untold numbers of visitors to the museum over the decades, James has not yet met Joaneath in person but has come to know her, as much as one can, through her work.

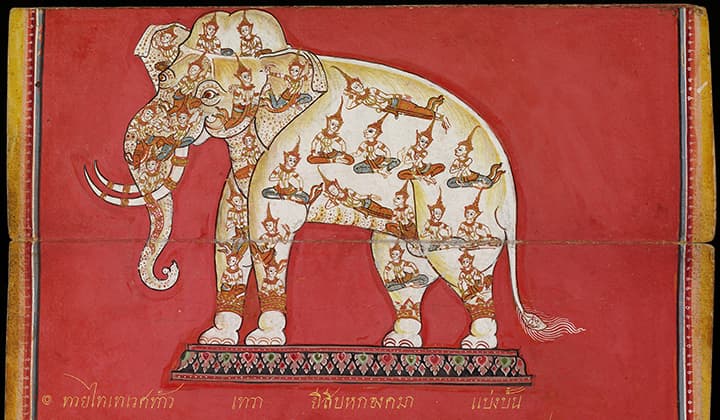

This volume is blessed with a wide variety of notes, which are appropriate because for Joaneath Spicer, everything in the world holds both endless interest and potential. Five of the notes in this issue are additional offerings in honor of the breadth of Joaneath’s interests, which often expand beyond the realm of Europe into Asia and even into the ancient past.[11] The topics published here include tracing ancient Roman sculpture from the Renaissance to the present, the inspiration and artistry of the Viceroyalty of Peru, “spicy” humor of late medieval art, technical research on a painting that expands the artistic narratives of the collection, and a nuanced assessment of the impact that Joaneath’s exhibition Activating the Renaissance had on museum visitors. Two further notes are welcome additions: one on revolving Chinese vases that connects with Joaneath’s interest in ingenuity and clever devices, and another on nineteenth-century paintings by Jean-Léon Gérôme that brings us back to the deep studies of a single artist of the type with which Joaneath began her career.

It is, in a very literal way, impossible to summarize Joaneath as a colleague. She is a persistent, direct, and pioneering scholar, who is at once warm but demanding, on occasion in need of assistance yet also known to be incredibly helpful, a fierce defender and an exacting critic. A sometimes complicated individual, she also brings a sense of wonder and whimsy to all her endeavors, although one that is firmly rooted in the nuanced accuracy that comes from meticulous research. She is creative and quirky, sometimes sharing stories of her life that are inflected with magical realism. Every year on her birthday, Joaneath turns 57 years old. Joaneath is often enormously funny (usually intentionally), yet she can tell only three jokes, one of which is dirty. If Joaneath informs you that someone has offered the museum a previously unknown but vastly important Rembrandt painting as a gift, you should check the date, because it’s probably April 1. When you ask her about the most famous people she’s ever met, be prepared to be amazed. She speaks of each new project, every potential acquisition with palpable enthusiasm, creating a sympathetic communion with the piece and engaging her audience with its possibility. Joaneath sees the world through the filter not of rose-colored but of iridescent glasses, yet her favorite object at the museum is a humble but elegantly made mug from Classical Greece (fig. 3). She is a person who is interested in everything and has something to offer to any discussion, well beyond even the range of topics mentioned so far. And so, it is with love and admiration that we offer the contents of this volume to a woman who has given so much of herself to the museum and to the study of art.

Unidentified Greek artist, Ridged Cup, second half 5th century BCE, glazed terracotta, 2 11/16 × 3 13/16 × 3 1/8 in. (6.8 × 9.7 × 8 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, museum purchase, 1980, acc. no. 48.2446

Acknowledgments

The editors of this volume extend our deep appreciation to all of the authors who participated in the publication: Leslie King Hammond, Christopher Daly, Judith Mann, Pamela Smith, James Prosek, and all of the authors of notes. Thanks are also especially due to Hannah Prescott, Meredith Gill, Anthony Colantuono, Brooks Rich, Ellen Lupton, and Gabriella Sousa. Warm thanks are offered to the current and former Walters employees, especially Ellen Hoobler, Ashley Dimmig, Ani Proser, Anna Clarkson, Dany Chan, Earl Martin, and Jo Briggs, who contributed to the planning stages of this journal, including to this introduction.

[1] “The ‘Naer Het Leven’ Drawings: By Pieter Bruegel or Roelandt Savery?” Master Drawings 8, no.1 (1970): 3–82; and “The Drawings of Roelandt Savery, 1576‒1639” (PhD diss., Yale University, 1979).

[2] “The Renaissance Elbow,” in Jan Bremmer and Herman Roodenburgh, eds., A Cultural History of Gesture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992), 84–128.

[3] “Criteria for Breast Reconstruction Surgery: Another Viewpoint,” Annals of Plastic Surgery 6 (1995): 1–9.

[4] “The Exhibition: Lecture or Conversation?” Curator Magazine 37, no. 3 (1994): 185–97; and “Epilogue: Some Curatorial Thoughts on the Monographic Exhibition,” in Maia Wellington Ghatan and Donatella Pegazzano, eds., Monographic Exhibitions and the History of Art (London: Routledge, 2018), 302–308.

[5] See, for example, “Pontormo’s Maria Salviati with Giulia de’ Medici: Is This the Earliest Portrait of a Child of African Descent in European Art?” The Walters Members Magazine Summer 2001: 4–6; “Representations of Heliodorus’ Aethiopica in 17th-century European Art,” in Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and David Bindman, eds., The Image of the Black in Western Art, Volume 3, From the “Age of Discovery” to the Age of Abolition, Part 1: Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), 307–35; Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe (Baltimore: The Walters Art Museum, 2012) and the eponymous exhibition 2012–2013 (with Princeton University Art Museum); and the installation Activating the Renaissance, 2022–2023, at the Walters Art Museum.

[6] Recent acquisitions expanding representations of people of African descent include workshop of Hyacinthe Rigaud (French, 1659–1743), Balthazar, ca. 1700, museum purchase, 2018, acc. no. 37.2938; prints from a series by Nicolas de Larmessin (French, ca. 1645–1725), especially Le Grand Roy Mono-Motapa, Dom Mateo Lopes, and L’Illustre et Magnifique Cherif Muley-Arxid, 1680s, acc. nos. 93.177–79; circle of Adriaen van Ostade (Dutch, 1610–1685), Black Youths Smoking in a Tavern, ca. 1630–1640, museum purchase, 2019, acc. no. 37.2941; workshop of Govaert Flinck (Dutch, 1615–1660), Portrait of a Young Black Woman, 1650s, museum purchase, 2021, acc. no. 37.2944; and Willem van Herp (Flemish, 1614–1677), Tavern or Brothel Owner on a Veranda with Two of Her Staff and a Client, ca. 1650s, museum purchase, 2023, acc. no. 37.2950.

[7] “An ‘Antique’ Brass ‘Candlestick in the Shape of Hercules’ by Peter Vischer the Younger and Workshop,” The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 63 (2005): 65–71.

[8] For Joaneath’s recent attribution of three monumental panel paintings from the Walters collection to Dario di Giovanni, see “The Abduction of Helen: A Monumental Series Celebrating the Wedding of Caterina Corner in 1468,” The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 74 (2019) with related essays and notes by Pamela Betts, Karen French, Glenn Gates, Eric Gordon, Janet Stephens, and others, published in conjunction with the 2019 installation Paintings for a Venetian Palace.

[9] “The Role of Invention in Art and Science at the Court of Rudolf II in Prague,” Studia Rudolphina: Bulletin of the Research Center for Visual Arts in the Age of Rudolf II 5 (2005): 7–16. See also “Referencing Invention and Novelty in Art and Science at the Court of Rudolf II in Prague,” in Ulrich Pfister and Gabriele Wimböck, eds., Novita: Neuheitskonzepte in den Bildkünsten um 1600 (Munich: Diaphanes, 2011), 401–24.

[10] The Walters was proud to host the Baltimore Taxidermy Open for several years in the Sculpture Court, which was curated by Joaneath, from which came some of the specimens in the Chamber. In addition to acting as a judge, Joaneath was the originator of the “Aldrovandi Sur-Prize,” awarded to examples of inventive taxidermy that would have fooled the Italian naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605). The most recent winner of that prize was a “pygmy monoceros” created by Risa Reyes.

[11] See, for example, “The Shifting Identity of a Thai Buddha in Seventeenth-Century Europe,” in Henry Ginsburg and Will Noel, eds., A Curator’s Choice: Essays in Honor of Hiram Woodward = The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 64–65 (2006): 207–10; and “Donatello’s Reliefs of Adam and Eve, c. 1405: Mixing Inexperience with the Adaptation of a Roman Statuette Belonging to Ghiberti,” Proceedings of the Conference Donatello: Workshops, Patronage, Revival, 19–20 May 2023, forthcoming.

Editorial Board

Lisa Anderson-Zhu, Curator of Ancient Mediterranean Art and of Provenance and Volume Editor

Ruth Bowler, Director of Publication and Digital Production

Gina Borromeo, Senior Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs and Senior Curator of Ancient Art

Adriana Proser, Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Quincy Scott Curator of Asian Art and Chief Curator

Julie Lauffenburger, Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director of Conservation, Collections, and Technical Research

Laurel Miller, Director of Visitor Experience

Theresa Sotto, Director of Learning and Community Engagement

Melanie Lukas, Copyeditor

Copyright 2024 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland, 21201

This volume was made possible through the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Fund for Scholarly Research and Publications, the Sara Finnegan Lycett Publishing Endowment, and the Francis D. Murnaghan, Jr., Fund for Scholarly Publications.

The redesign and digitization of the Journal was made possible by a grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Volume 77

A Wonder at the Walters: Essays in Honor of Joaneath Spicer

Joaneath Spicer once said she was born on the third floor of the Walters Art Museum. In point of fact, she first came to the museum just over thirty years ago as the James A. Murnaghan Curator of Renaissance and Baroque Art, and since that time has made an indelible mark on the institution. A prolific writer, lecturer, and mentor, Joaneath’s contributions as a scholar, curator, and colleague extend well beyond the walls of the museum and art history. Joaneath has expanded scholarship in Renaissance and Baroque art as well as brought the arts of antiquity, of the contemporary world, and even zoology and taxidermy firmly into conversation with the works she stewards. Yet, perhaps Joaneath has correctly ascribed the place of her “birth,” as the art, people, and spaces at the Walters Art Museum have directly contributed to who she is today (fig. 1). In celebration of her over thirty-year career at the Walters, this volume of the Journal of the Walters Art Museum is dedicated to Joaneath Spicer and her incredibly wide-ranging scholarly and curatorial interests.

About this Volume

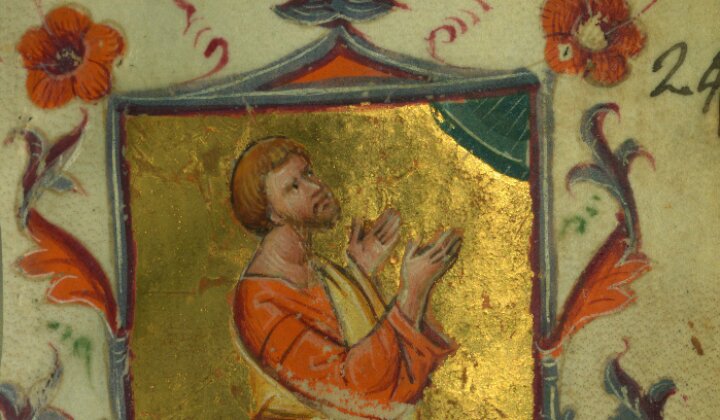

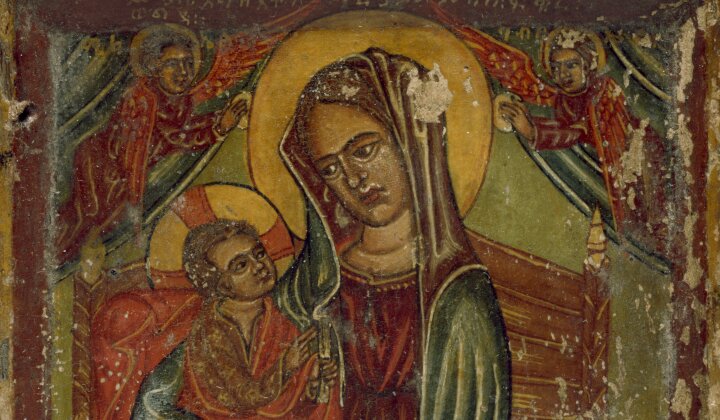

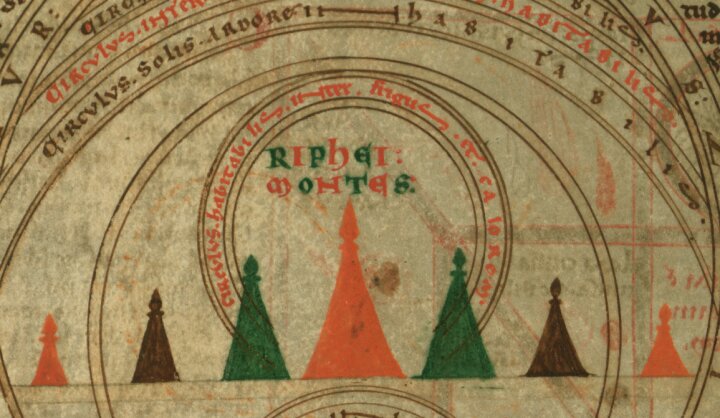

Seeing Codicologically: New Explorations in the Technology of the Book

Do you know how to use a codex? Of course you do! A codex is a book. You open the cover, read the first page, turn it, read the next page, and so on. It would seem simple enough, but of course not every book works in precisely this way. Think of a dictionary, or a child’s “choose your own adventure” book, both of which are explicitly designed not to be read in a linear fashion. Think of a travel guide with foldout maps or a Torah scroll that requires unfurling. Think about the webpage on which this journal issue appears, as you click on links and open new tabs. There are many ways a book might be designed to be used, and more ways that it might be used unexpectedly. Historically, research on decorated medieval manuscripts has tended to see the codex form of books as “normal” and to assume that the books were used linearly, if use was considered at all. Scholars have often considered individual illuminated pages as stand-alone images divorced from their material context, although more recent studies have emphasized the “opening”–two pages that face each other when a codex is open–as a crucial structural framework for understanding the interplay between words and images in manuscripts. Current scholarship has also reminded us that medieval manuscripts are more than words and images and certainly more than just codices: they are parchment, paper, textiles, wood, leather, metal hardware, and even the physical traces of the humans who have leafed through them, made annotations and erasures in them, hidden things within their pages, and kissed them.

In October 2019, scholars gathered for a two-day workshop at the Walters Art Museum and Johns Hopkins University to consider medieval manuscripts as complex technologies that could be used in many different ways, some intended and others unexpected.[1] The Walters, as a repository for an extraordinarily rich collection of nearly 1,000 manuscripts and a leader in the field of book digitization, provided an ideal environment in which to explore new approaches to understanding these unique objects, while the professors and students in the department of the History of Art at Johns Hopkins’ have long been important intellectual partners in the field of medieval art and manuscripts. The workshop brought together scholars whose research explored unusual manuscripts in creative and non-traditional ways, as well as “conventional” manuscripts in unconventional ways, with the goal of discussing their work in a spirit of collaboration and shared discovery.[2] Those explorations, and the lively conversations that the gathering inspired, resulted in the essays in this volume of the Journal of the Walters Art Museum, and feature groundbreaking work on manuscripts from the Walters collection and beyond. We hope that with these essays we have taken another step toward better understanding of the structural capacities of manuscripts and how they worked to produce meaning and social value among their beholders.

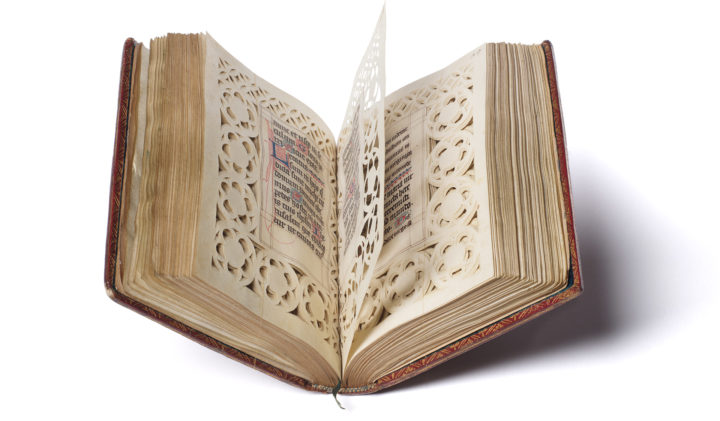

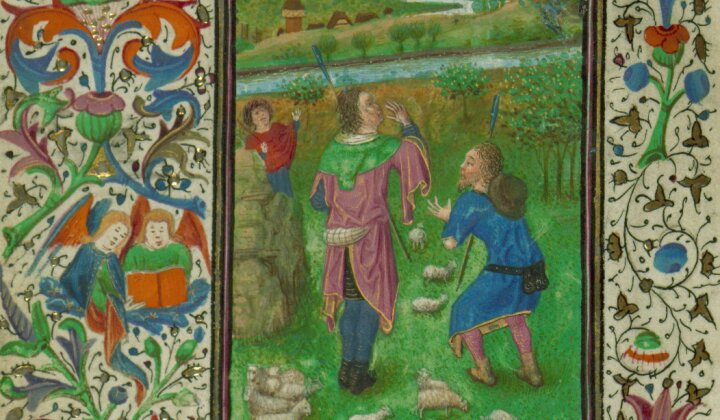

The first three essays consider transformation of the page, whether through the interactions of images and words as the book is opened and closed or by making physical alterations to the page. Just as scholars often talk about “openings,” Benjamin Tilghman considers how illuminations can interact and take on new and poignant meanings as they come together in “closings,” while Nicholas Herman contemplates how viewers can be privy to internal conversations between a book’s illuminations by means of openings cut through the pages. Lynley Herbert examines cutting in a different way, exploring how parchment could be transformed into something evoking lace, or even deeply chiseled stone.

The assumption that the standard codex is the ideal structure of medieval books is reconsidered in Sonja Drimmer’s discussion of the coexistence of the same text in both roll and codex forms and Christine Sciacca’s examination of how folding devotional imagery found in Ethiopian sensuls takes on the codex form but does not function as one. A book’s structure can also be unusual in less overt ways, as Adam Cohen notes in the discussion of a Hebrew Bible that has been “wrapped” in another text to create a complex and deeply meaningful experience for the reader. Stepping back and looking at illuminations from a different perspective can also be enlightening, as Shirin Fozi-Jones demonstrates by reframing of Romanesque “portraits” as avatars or representatives for generations of the book’s users, while Kate Rudy investigates the results of artists’ attempts to imitate novel forms of book decoration without fully making use of the techniques involved.

The idea for this project emerged in part in response to the spread of digitization and new media initiatives in manuscript studies, and across our multimedia environment more broadly. Digitization has made manuscripts accessible to audiences of many backgrounds around the world, and they have enhanced scholars’ research by making our objects of study more widely available. Yet, as many have argued, the digital surrogate and the original manuscript are themselves different kinds of objects. As the digital has taken center stage in academia as well as an increasingly important place in museums, scholars have turned newly appreciative eyes to the material properties of the non-digital object, recognizing that the future of manuscript studies rests in the ability of scholars to use new technology in concert with the exploration of the physical books. Publishing these findings in a digital journal is a way to take advantage of the best aspects of these new technologies, allowing this scholarship to reach a broader audience, and providing that audience opportunities to explore these manuscripts along with us. We hope you will enjoy that journey, and that it will spark a new sense of wonder and appreciation for quirky codicology!

Lynley Anne Herbert, Walters Art Museum

Benjamin C. Tilghman, Washington College

Sonja Drimmer, UMass-Amherst

[1] Workshop participants, many of whom contributed essays to this volume of the journal, included Adam S. Cohen, Sonja Drimmer, Shirin Fozi, Lynley Herbert, Nicholas Herman, Christopher Lakey, Kathryn M. Rudy, Alexa Sand, Christine Sciacca, Benjamin Tilghman, Nino Zchomelidse. Special thanks to Abigail Quandt, Walters Head of Books and Paper conservation, who generously shared with participants her deep knowledge of the collection and of medieval manuscripts in general.

[2] This workshop would have been impossible to plan and execute without the assistance of the Walters’ staff, especially Diane White, administrator to the executive office, who made all of the arrangements for the participants. We are also grateful for the assistance of Ashley Costello, Senior Administrative Coordinator in the Department of the History of Art at Johns Hopkins University, and for the funding and hospitality provided by the JHU Department of the History of Art. Additional funding was graciously provided by the Mellon Society of Fellows in Critical Bibliography.

The citation for the essay portion of this volume is:

Lynley Anne Herbert, Benjamin Tilghman, and Sonja Drimmer, eds, Seeing Codicologically: New Explorations in the Technology of the Book. The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 76 (2023), https://journal.thewalters.org/volume/76/essay/looking-through-books/

Editorial Board

Lynley Herbert, Volume Editor

Sonja Drimmer and Benjamin C. Tilghman, Guest Volume Editors

Melanie Lukas and Lisa Anderson-Zhu, Copyeditors

Ruth Bowler, Director of Publication and Digital Production

Lisa Anderson-Zhu, Associate Curator of Art of the Mediterranean

Julie Lauffenburger, Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director of Conservation, Collections, and Technical Research

Copyright 2023 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland, 21201

This volume was made possible through the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Fund for Scholarly Research and Publications, the Sara Finnegan Lycett Publishing Endowment, and the Francis D. Murnaghan, Jr., Fund for Scholarly Publications.

The redesign and digitization of the Journal was made possible by a grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Volume 76

Seeing Codicologically: New Explorations in the Technology of the Book

Do you know how to use a codex? Of course you do! A codex is a book. You open the cover, read the first page, turn it, read the next page, and so on. It would seem simple enough, but of course not every book works in precisely this way. Think of a dictionary, or a child’s “choose your own adventure” book, both of which are explicitly designed not to be read in a linear fashion. Think of a travel guide with foldout maps or a Torah scroll that requires unfurling. Think about the webpage on which this journal issue appears, as you click on links and open new tabs. There are many ways a book might be designed to be used, and more ways that it might be used unexpectedly. Historically, research on decorated medieval manuscripts has tended to see the codex form of books as “normal” and to assume that the books were used linearly, if use was considered at all. Scholars have often considered individual illuminated pages as stand-alone images divorced from their material context, although more recent studies have emphasized the “opening”–two pages that face each other when a codex is open–as a crucial structural framework for understanding the interplay between words and images in manuscripts. Current scholarship has also reminded us that medieval manuscripts are more than words and images and certainly more than just codices: they are parchment, paper, textiles, wood, leather, metal hardware, and even the physical traces of the humans who have leafed through them, made annotations and erasures in them, hidden things within their pages, and kissed them.

About This Volume

Foreword to Volume 74

Welcome to the first completely digital volume of The Journal of the Walters Art Museum! The Journal is the oldest continuously published scholarly art museum journal in the United States. With volume 73, we transitioned from the paper format to an online pdf version; we are now delighted to make the Journal’s contents freely accessible to all by presenting this and future volumes in a fully digital format.

The first volume of the Journal appeared in 1938, only four years after the museum opened as a public institution. Its preface noted that Henry Walters had “left to scholars the task and the adventure of seeking out the full significance of these things, so that the public may benefit by the knowledge and enjoyment of its heritage. The studies published here are intended to contribute to this purpose.” Over the next eighty years and seventy-three volumes, the Journal has continued to publish research on or related to the Walters’ collections, written by distinguished scholars on staff and from around the world.

In the same way that the original intent of the Journal encompasses both scholarship and public benefit, we aim to make research on the collection and the collections themselves as accessible as possible to ever wider and more diverse audiences. While they present specialist research from an array of perspectives–including those of art historians, conservators, conservations scientists, and museum educators–the essays and notes are intended to be read by general audiences, with minimal jargon and technical language. The Walters Art Museum is committed to providing free and open access to its collections, both to onsite visitors through free admission, and digitally through its online collections and open access policy. Digital images of works of art in the Walters’ collections considered to be in the public domain (no longer protected by copyright) are available for use without limitation, rights- and royalty- free. The museum has adopted the Creative Commons Zero: No Rights Reserved or CC0 license to release copyright and allow for unrestricted use of digital images and metadata by any person, for any purpose. Similarly, the contents of this Journal are made available through the museum’s website without fees, subscriptions, or passwords; the essays and notes published here are available to access and share. No permissions are needed. More information on citing and crediting Journal content can be found here .

The digital format allows new ways of engaging with information about the collections. In this volume, in addition to beautifully designed text and high-resolution images, you will find tools that allow you to explore before-and-after views of paintings that have undergone conservation, and an animation that demonstrates how raking light reveals textures. The fully digital design allows quick transitions, and hyperlinked content. Although we will no longer produce a paper version of the Journal, the essays and notes have been formatted for easy printing and for downloading and reading offline. The Editorial Board is deeply grateful to WDG for web development support; to the contributors to this volume; and to Ruth Bowler, Head of Imaging and Intellectual Property, and Dylan Kinnett, Web Manager, for their tireless efforts and expertise in bringing this project to fruition.

The essays and two of the notes in this volume focus on the results of a complex, multi-year investigation and treatment of three large-scale fifteenth-century panel paintings depicting the abduction of Helen of Troy. They examine the paintings from an array of perspectives, historical, art-historical, and technical, bringing to light the life of these extraordinary works of art. Through these examinations, you will discover the stories of their commissioning, who made them, how they were made, where they were hung, what they depict, and how they have been conserved over the course of their history, as well as revelations about the astonishing use of Pressbrokat, or applied brocade, to create sumptuous surfaces and the recipes used by Venetian ladies to achieve the blond tresses that contributed to Helen of Troy’s fabled beauty. Other notes included in this volume provide first looks at new acquisitions, explore the Walters’ fascinating portrait mummies, and describe the innovative restoration of the decorative plaster walls in the library at 1 West Mount Vernon Place, revealed to the public in June 2018. Our next issue will focus on ceramics in the Walters’ collections, through the lens of the first installations at 1 West.

Volume 75

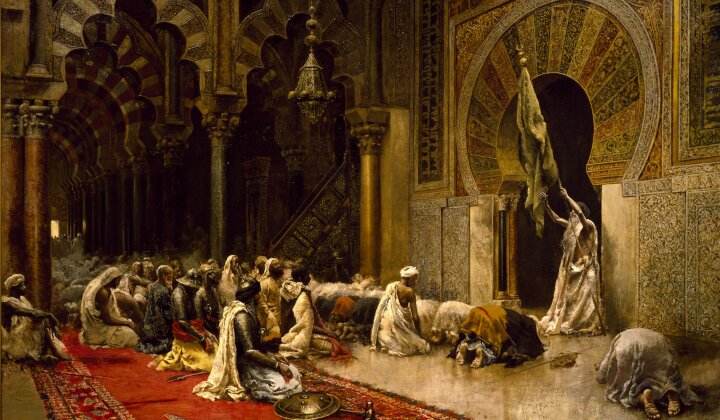

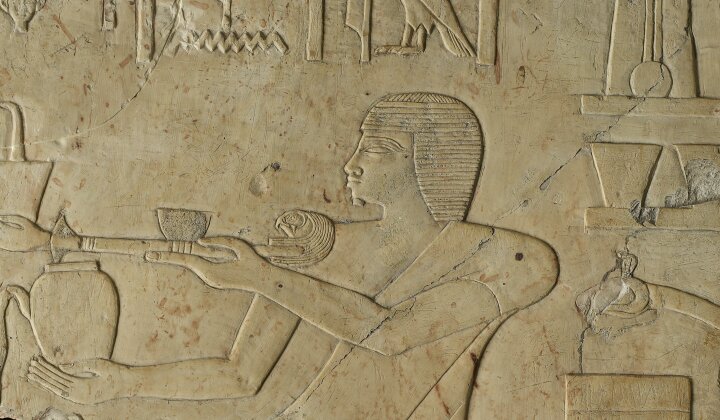

Introduction

Clay is fundamental to creation stories across the globe: Khnum, the ancient Egyptian deity, was said to mold children from clay and place them in their mother’s womb; in Greek legend Prometheus made the first humans from clay and animated them with fire stolen from the gods; in Jewish tradition a golem fashioned from clay can be animated by written spells. Similar stories exist in African and indigenous American culture, in the Qur’an, the Hebrew Old Testament, and Hindu mythology. In each case clay represents a pre-existing chaos out of which the bodies of humans are formed by an inspired or divine potter. Clay therefore has a fundamental place in global culture, and ceramics are the original material of creative expression.

About This Volume

Foreword to Volume 75

Clay is fundamental to creation stories across the globe: Khnum, the ancient Egyptian deity, was said to mold children from clay and place them in their mother’s womb; in Greek legend Prometheus made the first humans from clay and animated them with fire stolen from the gods; in Jewish tradition a golem fashioned from clay can be animated by written spells. Similar stories exist in African and indigenous American culture, in the Qur’an, the Hebrew Old Testament, and Hindu mythology.[1] In each case clay represents a pre-existing chaos out of which the bodies of humans are formed by an inspired or divine potter. Clay therefore has a fundamental place in global culture, and ceramics are the original material of creative expression.[2]

Roberto Lugo, Slave Ship Potpourri Boat, 2018, porcelain, china paint, luster. The Walters Art Museum, Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 2018, acc. no. 48.2882

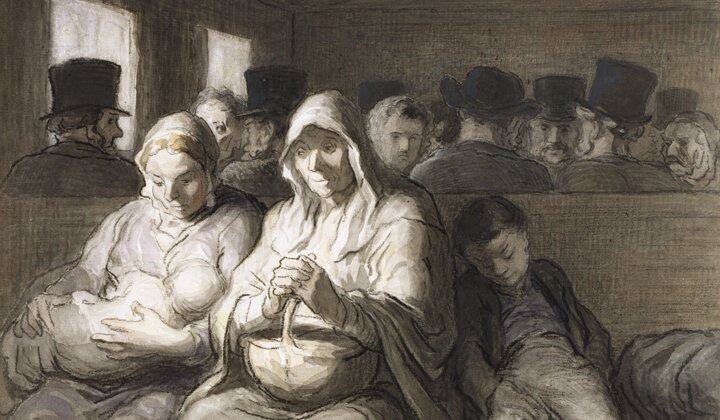

As curators and academics seek an expanded vision of art history, the worldwide resonance of ceramics offers a fascinating opportunity. The Walters Art Museum recently re-committed itself to telling global and inclusive stories with its art treasures; in 2018 the museum’s nineteenth-century townhouse at 1 West Mount Vernon Place, which had been newly refurbished, was filled with a cross-departmental display of ceramics. The exhibit encompassed some of the oldest and newest objects in the collection, spanning pre-history to the present.[3] Members of the public, led by educator Herb Massie, contributed hundreds of plates, grouped to form a mosaic, while contemporary ceramicist Roberto Lugo created site-specific work reflecting on the history of the house and those that had lived and worked there, particularly the enslaved cook, Sybby Grant. Lugo’s powerful Slave Ship Potpourri Boat (fig. 1) based on a Sèvres Vase pot-pourri à vaisseau in the Walters’ collection, which was part of this installation, is discussed in this volume by Chi-ming Yang.

Historically, ceramics were a strength of the collections that now form the core of the museum. During the Gilded Age, William T. Walters (1819-1894) collected a large number of Asian, and a smaller number of European, ceramics. The most famous object he owned was an early eighteenth-century “three-string” Chinese vase, famed in the nineteenth century as the “Peach-Blow” or “Morgan” vase. Henry Walters (1848-1931), William’s son, greatly expanded this collection. Following both the aesthetic enthusiasms and prejudices of his time, he purchased Greek vases, Renaissance maiolica and della Robbia ware, Islamic lusterware, and European porcelain, as well as a great many more ceramics from Asia.[4] On Henry’s death, his collection of over 20,000 objects was given to the city of Baltimore. Since that time, major gifts have broadened the Walters’ collection to include ceramics from the ancient Americas donated by John Bourne, contemporary Japanese ceramics from the Betsy and Robert Feinberg collection, and nineteenth-century British and American majolica, the gift of Deborah and Philip English. This most recent addition, accompanied by the Englishes’ endowment of a curatorial position in the areas of decorative arts, design, and material culture, is the occasion for this special issue of the Journal of the Walters Art Museum dedicated to ceramics. It also coincides with the exhibition Majolica Mania: Transatlantic Pottery in England and the United States, 1850-1915, co-curated by Susan Weber, Director of the Bard Graduate Center, and myself, and the publication of a three-volume book with the same title, edited by a team of curators at the Bard and the Walters. Both exhibition and publication are supported by the Englishes and feature rare and exceptional works from their collection.

Matilda Charsley (1823-1904), designer; Minton & Co., manufacturer. Lobster Dish, 1869, glazed earthenware. The English Collection.

Majolica Mania aims to rehabilitate a ceramic type celebrated in the Victorian era, but which fell out of favor with the advent of modernism. Scholars working on the project collaborated to combine business history, labor law, studies of immigration, and the history of exhibitions and collecting, in a broad approach encompassing both the precious and the mundane. I was struck by the way that majolica, often used in spaces where nature encroached into the domestic sphere, the conservatory or kitchen, marked a boundary between raw and cooked, or clean and dirty.[5] For example, a pinkish-red lobster perches atop a majolica tureen for seafood (fig. 2), while foxgloves and leaves impressed on a flower pot hide dirt and roots (fig. 3). Essays in this volume reveal that other ceramics also perform this function of boundary marking: between species, geographies, and races, in the case of a pair of Sèvres elephant-head vases discussed by Chi-ming Yang; between the interior and exterior of the body in the case of an allegorical group of the five senses manufactured by Meissen as analyzed by Michael Yonan, and, self-consciously, even playfully, between Japanese and Chinese culture in the case of a blue-and-white vase in the form of a lotus flower, the focus of Sonia Coman’s contribution.

Minton & Co., Fern and Foxglove Garden Pot and Stand, designed ca. 1851, this example 1866, glazed earthenware. John Stacke Graham Collection

Each author in this volume takes a different approach to ceramics in the Walters Art Museum, but unifying themes emerge about global exchange and influence across medias, as well as, more abstractly, the theme of boundaries noted above. Yonan foregrounds the materiality of European porcelain through a series of close readings, which lead in a surprising direction. He boldly, but convincingly, proposes a shift in European material culture with the introduction of porcelain, akin to the shift which accompanied the introduction of one-point perspective in painting that redefined the subjectivity of the beholding individual. He writes, Europeans “created porcelain, but porcelain also created them.” Yang also reads her chosen objects closely, but also employs a kaleidoscopic range of sources, drawn from zoology, the history of science, and the pseudo-science of race, shedding light on what she identifies as “the eighteenth-century fascination with highly sensitive, racialized surfaces, from human skin to sculptural glaze.” Coman offers an in depth reading of a single object, a lotus-shaped vase. The vase is a Japanese adaptation of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain and tea culture, but the anachronic references it plays with, as well as the range of materials and types of symbols that it invokes, give it the quality of a palimpsest, which collectors, and even contemporary viewers, add to, whether the full significance of the vase’s associations are fully grasped or not.

Enjoy!

Jo Briggs

Volume Editor

With the expansion of the collection and the curatorial team at the Walters through the Englishes’ generous and transformative gifts, the stage is set for more ceramic objects, both famed and neglected, to receive the in-depth scrutiny the authors in this volume demonstrate that they merit.

[1] David A. Leeming, Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara: ABC CLIO, second edition, 2010), vol. 1, pts 1-2, “Clay based creation,” p. 312; Patricia Ann Lynch, revised by Jeremy Roberts, African Mythology: From A to Z (New York: Chelsea House, 2010), see entry “Humans, Origins of,” pp. 52-53; see also Lorena Stookey, Thematic Guide to World Mythology (Westport and London: Greenwood Press, 2004).

[2] As Michael Yonan notes in this volume, “Ceramic objects are among the oldest surviving artifacts of human history; the only tangible record we have from which to reconstruct some historically remote cultures is their pottery.”

[3] This approach has precedent at the museum: the volume Jewelry: Ancient to Modern was published in 1979, and Masterpieces of Ivory followed in 1985. See Anne Garside (ed.), Jewelry: Ancient to Modern (New York: Viking Press, and the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, 1979); Richard H. Randall, with Diana Buitron, Jeanny Vorys Canby, et al., Masterpieces of Ivory from the Walters Art Gallery (New York: Hudson Hills Press and the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, 1985). Other cross-collection projects have included a traveling exhibition of jewelry, Bedazzled: 5000 years of Jewelry (2008-2009), and a focus show, The Allure of Bronze (1995), curated by Joaneath Spicer, Murnaghan Curator of Renaissance and Baroque Art. Looking back to Henry Walters’ original displays at the museum in the early twentieth century, cases and some galleries, were organized by material.

[4] See Bill Johnston, William and Henry Walters, Reticent Collectors (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999). The vase was named for the collector Mary J. Sexton Morgan (1823-1885), and sold in 1886 at the American Art Association in New York. Johnston, Reticent Collectors, pp. 96-99.

[5] Jo Briggs, “Molding meaning: majolica in a Transatlantic context, from Cole to Haynes, from Ruskin to Eastlake,” volume 1, chapter 6 in Weber, Arbuthnott, Briggs, et al. eds, Majolica Mania: Transatlantic pottery in England and the United States, 1850-1915 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), pp. 145-171.

Editorial Board

Jo Briggs, Volume Editor

Melanie Lukas, Copyeditor

Ruth Bowler, Director of Publication and Digital Production

Lynley Herbert, Curatorial Chair

Julie Lauffenburger, Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director of Conservation, Collections, and Technical Research

Copyright 2021 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201

Special grants from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation supported scholarship and made possible the redesign and digitization of the Journal.

This publication was made possible through the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Fund for Scholarly Research and Publications, the Sara Finnegan Lycett Publishing Endowment, and the Francis D. Murnaghan, Jr., Fund for Scholarly Publications.

Volume 74

The Journal of the Walters Art Museum

Foreword to Volume 74

Welcome to the first completely digital volume of The Journal of the Walters Art Museum! The Journal is the oldest continuously published scholarly art museum journal in the United States. With volume 73, we transitioned from the paper format to an online pdf version; we are now delighted to make the Journal’s contents freely accessible to all by presenting this and future volumes in a fully digital format.

READ MORE