Taken as a whole, the history of ceramics is a domain both enticing and daunting. Ceramic objects are among the oldest surviving artifacts of human history; the only tangible record we have from which to reconstruct some historically remote cultures is their pottery. This gives ceramics an “ancientness” that few other media in the history of art can parallel. Yet in addition to being durable enough to survive over millennia, ceramic objects are also ubiquitous in the contemporary world. Today, almost everyone owns something made out of a ceramic medium, most likely cheaply produced commercial stoneware, if not more exalted examples such as bone china or porcelain. Ceramic objects used for mundane purposes are far removed from the distinctive ceramic creations housed at the Walters Art Museum. Ceramics also comprises an artistic outlet widely available to non-professionals, the hobby artists whom art history sometimes neglects to acknowledge. This makes ceramics one of the more approachable artistic media, one that the general museumgoer is most likely to find familiar. But it is precisely this ubiquity across historical eras, global cultures, and social classes that makes ceramics challenging to conceptualize.[1] What interpretive strategies could possibly apply to such a diverse realm of objects—both rare and mundane—present throughout millennia, and with seemingly infinite cultural associations?

There is a concept, however, that offers a potential starting point for building a shared interpretive framework for this vast array of ceramic things. This is the idea of materiality. The term now appears regularly in scholarly writings from literary studies, history, archaeology, and anthropology. Perhaps materiality has come to lack the punch it once bore during the “material turn” that took place in the academy some twenty years ago, since it is now used to describe anything physical.[2] For many beholders, an object’s physicality is synonymous with its materiality. This is a rather generic use of the term, one that lacks depth, but there are other ways to think about materiality that offer more specific possibilities. Materiality’s vagueness will not deter me from claiming that it is a concept of singular importance to the history of art and especially to the decorative arts, which include ceramics. To that I must add the qualification that materiality is a concept best understood expansively. By virtue of how they are made and apprehended, as well as their historical prominence, ceramics are material entities par excellence, and I would suggest that understanding them through the lens of materiality offers a particularly fertile framework for interpretation that can be applied to the entire range of ceramic objects.

I would like to note that strictly speaking, materiality and its related domain of “material culture” are not precise methodologies, although both can be used as the basis for building methodological systems of various kinds. Material culture is not the equivalent of the social history of art or feminist art history: it has no procedures or terminology specific to it and no unified set of concerns that it seeks to elucidate. Yet there have been attempts to do just that for the discipline of art history. Jules David Prown formulated a material culture methodology in his now classic essay of 1982, a text that is still extremely valuable for theorizing material culture studies.[3] Readers seeking a set of procedures to follow in order to understand the materiality of ceramics would be advised to consider Prown’s process of description, deduction, and speculation, which charts out an excellent track to analyzing an object from a past culture. I would like to expand on Prown’s insights to propose that we think of materiality as a register of meaning, a dimension of how one apprehends an object that can be incorporated into various methodological approaches. Borrowing a term from linguistics, one could understand materiality as a suprasegmental dimension of art interpretation: something that applies to more than one aspect of it and that can be acknowledged in various ways. Materiality can inflect multiple ways of talking about art, and thinking about the materiality of an object will enrich whatever interpretations the scholar pursues. This essay explores how that can happen by looking carefully at selected ceramics in the Walters’ collection produced by the Meissen porcelain manufactory in Dresden, Germany.

First, it will be helpful to dwell further on the various ways that the term materiality can be defined. One component of a work of art’s materiality is its medium. As materiality comes into wider usage as an art-historical term, scholars sometimes use it as a more exciting replacement for its older, blander predecessor. This is unfortunate, as medium and materiality are not in fact coequal. Medium identifies what something is made of. Of course it matters enormously whether a painting is in oil, tempera, or acrylics: the possibilities that each medium allows, as well as the limits that it proscribes, are essential components of a work of art and ideally should play a role in its scholarly interpretation. But its medium also needs to be understood within the broader materiality of the culture in which it was made. This is to say that an object’s medium is part of a material world, which is specific to its moment and its culture of production. Materiality is therefore forever in flux, and materialities function differently within different settings. Imagining how an object’s medium fits within the philosophical, ethical, perceptual, and economic structures of a given moment is a way of understanding its materiality, and this produces a much broader and potentially more profound understanding of its historical significance.

Materiality is therefore a bigger idea than medium, one that comes with both distinct advantages for the interpreter as well as some intimidating challenges. Its usefulness lies squarely in its scope; by thinking about materiality, one can position an object in cultural systems using aspects beyond the usual art-historical categories of function, iconography, and style. Its challenge is also precisely in its scale: once one realizes that an object is part of a much broader material realm, the more one will struggle to describe that realm. And furthermore, materiality is a slippery entity that will never lend itself to easy summarization; elsewhere I have described it as “an elusive combination of physical substance, tactility, medium, and objecthood,” which together describe the integrity of the object as a discrete entity separate from, but related to, other entities and from human consciousness.[4] This is a quasi-anthropological definition developed from the scholarship of Daniel Miller, whose writing on materiality has been most provocative and suggestive for my own practice. Miller approaches materiality through a broader definition of material culture, for which he distinguishes two kinds. There is a basic material culture that encompasses the history of objects; he dubs this the “vulgar” definition and it is, for better or worse, what most people mean when they use the term. There is also a more expansive definition. It draws attention to the process by which a society produces itself materially, but also how material creations produce the society in return and indeed on some level are that society. He also proposes that materiality is not something that people engage with as predetermined, autonomous subjects, but rather that the material world is both produced by and produces the people who exist in it. To use his words, “humanity is not prior to what it creates…what is prior is the process of objectification,” that which gives form to things and creates the appearance of a discrete subject/object dichotomy.[5]

Readers familiar with poststructuralist theory will recognize Miller’s debt to a range of prominent thinkers, but we need not get mired in their specific arguments in order to understand the larger point, which is that material possibilities produce the world, and that people both make and are made by the material possibilities of the world they engage.[6] Elsewhere Miller states that once one understands materiality in this way, it leads to the conclusion that everything is constituted materially, including unlikely categories such as the ephemeral, the imaginary, the biological, and the theoretical.[7] Materiality is then a constituent component of culture, and it is furthermore a historical process that changes over time. It is also, rather paradoxically, that aspect of material culture that does not lend itself to full apprehension by the observer, since there is always a dimension of materiality that escapes description. The reason for this is partly one of language, as philosophers beginning with Aristotle have struggled to find a way to describe matter and how it operates. Part of it is also the physical nature of materiality, which by definition is not something that can be absorbed completely into the interpreter’s consciousness.

These may seem like rather abstract divagations, and perhaps they are, but they will become easier to understand if we recognize that materiality is a corollary to the much more familiar idea of representation. Representation is a commonly used term among art historians. One could understand the discipline’s entire purpose to be comprehending the ways in which images are made and, subsequently, how those images operate in specific cultures at specific historical moments. Writings from art history follow this track all the time. As an example, we can think of the familiar argument that one-point linear perspective grew from a new conception of the human subject, and that, once it proliferated in art, the sense of humanity’s place in the world changed as a result of this new way of representing human beings in space. A specific representational system was born from and then changed the people who engaged with art produced according to that system. We need alter the language only slightly to arrive at a similar version of that story based on materiality rather than representation. Instead of asking “How did Renaissance Europe represent the world in images?”, we could pose the following: “How did Renaissance Europe materialize the world through objects?” This would immediately change our focus to a consideration of the kinds of materials available to artists five hundred years ago, and how those materials brought about a new understanding of the world. Oil paint, tempera, lapis lazuli, rare woods, marble, and other such materials would become central to our discussion. We would replace an interpretive structure rooted in visual culture to one rooted in material culture; but I would add that everything, from knowledge to social structures, is encoded in a material process, image-making included. There is important work being done in this vein, and not just on Renaissance art. My point is much broader, however: materiality should undergird the entire study of art and of objects more broadly defined; indeed, it should be a primary basis for studying everything. Without a sense of the material’s stake in creating human experience, something will always be lost in scholarly evaluations of history and society. We could note as well that the former question presented above approaches art in a way that prioritizes the sense of sight, and therefore optically, while the latter does so by prioritizing touch, or haptically. There is much more that can be said about the haptic dimension of art works, particularly in the realm of the decorative arts, as it may in fact provide access to the materiality of objects and, by extension, the material dimension of history.

I shall now make the rather bold assertion that a material equivalent to the revolution in vision implemented by the development of one-point linear perspective took place, and it did so in the realm of ceramics, and more specifically in porcelain. Porcelain emerged in China in the years around 600 CE, and after much experimentation the recipe for it was recreated at Meissen in 1708.[8] Porcelain is a unique and special ceramic medium, the distinctiveness of which contributed profoundly to the way in which Europeans understood the world.[9] It is hard for us to reclaim that sense of wonder when we encounter porcelain today, and unfortunately the terminology used to describe porcelain tends to confuse its material effects. So before further examining porcelain’s historical importance, I will take a moment to describe the material qualities that made (and make) it so special. There is an important distinction to be made between hard-paste and soft-paste porcelain, one often minimized in writing on ceramics, although the recent catalogue of European porcelain from the Metropolitan Museum of Art offers an important discussion of the difference.[10] True hard-paste porcelain is a substance with extremely unusual material properties. Soft-paste porcelain, on the other hand, is a catchall term for porcelain-like formulations produced in early modern Europe that possess some of the qualities of hard-paste porcelain but are not identical to it chemically.[11] Soft-paste porcelain has more in common with other kinds of ceramics; it tends to be heavier than hard-paste porcelain, and while it fires to a shine, its surfaces are typically rougher, more irregular, and less consistent in their optical effects. Hard-paste porcelain has notably more refined qualities. It fires true, which means that the product, when pulled out of the kiln, is white, hard, uniform in tone, and glossy. Properly fired hard-paste porcelain requires no glaze, although it can be glazed in additional firings, and it can also be painted. Hard-paste porcelain is unusually strong for its weight, belying its apparent delicacy, and, central to its visual appeal, both reflects and refracts light simultaneously. The distinction between soft- and hard-paste porcelain is likewise noticeable in the firing temperatures required for each. Hard-paste porcelain vitrifies only at extremely high temperatures, over 2280º F, while soft-paste can be made at much lower temperatures. Hard-paste porcelain is therefore trickier to produce, requiring greater care and attention from the ceramic artist.

These material distinctions are incredibly important when observing eighteenth-century porcelain objects, and yet they are typically subsumed under the idea of porcelain simply being a shiny white ceramic medium, which obscures hard-paste porcelain’s special qualities. Most distinctively, a true hard-paste porcelain object will broadcast its status through its interaction with light. Hard-paste porcelain is shiny, but that shine coexists with an absorptive translucence. Positioned in front of a light, the reflectivity of hard-paste porcelain abates and a warm matte quality takes over as light refracts through the ceramic medium. That warmth provides a subtle undertone to porcelain’s appearance, one not often noted in scholarly discussions of porcelain objects. Indeed, this complex process of absorption and reflection produces some of the optical effects that make it so attractive. Soft-paste porcelain typically lacks this quality; the shine it produces is glassier and more superficial, with less light filtering through the ceramic body. It is also usually heavier and thicker. These qualities are crucial elements of porcelain’s eighteenth-century materiality. It is not just that hard-paste porcelain was produced in Europe with great difficulty, that it was likened to gold, associated with powerful Asian societies, and was expensive, although all of these are part of its historical significance. Hard-paste porcelain was also an intervention into the European material world. This intervention started with the importation of porcelain objects from China in the medieval period, but expanded when Meissen began to produce hard-paste porcelain and put it to new uses. Hard-paste porcelain changed not just the nature of European ceramics, but also how those individuals who encountered the material understood the world. Following Miller, I would suggest that porcelain changed how Europeans understood themselves and the workings of culture, and that in creating objects made of hard-paste porcelain, they also produced a sense of how they wanted their culture to operate, one that had consequences well beyond the eighteenth-century collector. I think it is not unreasonable to conceive of porcelain’s materiality through a series of interlocked metaphors of the European elite self: sleek, refined, radiant, expensive, warm, and gleamingly white. That whiteness is telling: there is a racial dimension to porcelain that is also part of its materiality.[12] The first decades of porcelain’s European manufacture are therefore especially important in understanding how this material came to change and define European subjectivity. People created porcelain, but porcelain also created them.

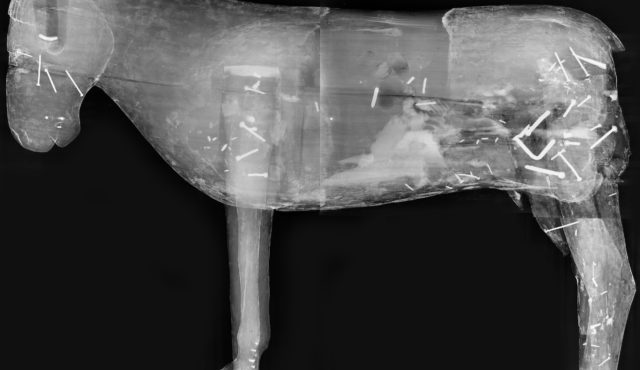

This brings us to specific porcelain objects, which in various ways exemplify the concept of materiality parsed out earlier in this essay. Many Meissen products made in the manufactory’s first decades celebrate the material’s whiteness, leaving the object unpainted in order to highlight the evenness of the white surface and enable its reflectiveness to be appreciated above all else, but later objects used porcelain’s whiteness as a surface for making pictures. As suggested earlier, we need not understand materiality and representation as two separately functioning systems of meaning production. If we conceive of materiality as a dimension of meaning, it can combine with other physical and pictorial elements of a work of art in arresting ways. Meissen’s designers undeniably recognized this possibility and began to make use of it in their designs. When applied to hard-paste porcelain, pigment combines the medium’s haptic and optic dimensions to create unusual and often quite beautiful effects. Here I can turn to a Meissen chocolate pot made around 1725 in the collection of the Walters Art Museum to illustrate how this happens (fig. 1). The composite construction consists of a body and lid made of hard-paste porcelain, combined with a handle made of ivory. The ivory handle adds monetary value and beauty, since ivory was a much-valued import material in early modern Europe, but it also serves a practical purpose. Ivory does not conduct heat well and so it would prevent the server’s hand from being burned while pouring hot liquids from the vessel. The ivory handle’s decorative simplicity contrasts with the elaborateness of the gilding and painting on the pot itself. In addition to the scenes rendered around it, the gilding creates reflective elements as well. Topping off the object on its lid is an animal, half Chinese guardian lion and half lapdog, that adds elements of exoticism and humor (fig. 2).

But what is the effect that porcelain has on this object’s decoration? Using porcelain as a basis for imagery influences how those images appear, namely how the pigments interact with the porcelain base beneath them. In this instance, the porcelain painter has incorporated porcelain’s whiteness into the pictorial structure of the scenes represented, with unpainted areas, like the sky, contributing to the picture’s illusionism (fig. 3). The white of the porcelain is used to convey the lightest tones in the modeling of figures’ garments, with darker pigment applied to give a sense of three-dimensionality in a manner similar to how an artist would convey folds of drapery in a painting. This approach is also employed in the landscapes depicted, as in the distant mountains or the foliage of the trees, resembling in that way drawings where the color of the paper is used as a base hue in modeling.[13] Porcelain’s materiality becomes part of the experience of apprehending this object in other ways as well. The reflective/refractive character of hard-paste porcelain lends a complex vivacity to the scene, in that light shines both on and through the painted areas, energizing them in a way that would not occur were these same pictures painted onto white-glazed clay. The effect is a bit like turning the brightness up too high on your computer screen; everything seems whiter than it should. Intelligent Meissen artists understood this visual potential inherent to the porcelain medium and painted scenes like the ones on this pot to take full advantage of its lucency. It is important to remember that these visual effects would have been appreciated in eighteenth-century settings accustomed to much lower levels of light than we typically experience today.[14] One can imagine the effects of this warm reflectiveness on viewers accustomed to darker, duller, more matte ceramic surfaces that reflected light less intensely. Something that I have not been able to test, but which I suspect is true, is that when a pot such as this was filled with a warm liquid, the heat generated would change in subtle ways how these light effects were perceived and thereby alter the overall apprehension of the pot. It was well understood in the eighteenth century that porcelain, be it hard or soft, was better at retaining heat than other types of ceramic, which alone would make it desirable for warm drinks, but that warmth would have created a multisensory experience, both tactile and visual.

Now to turn to the continuous scene depicted around the sides of the pot. All three of the materials associated with this object—porcelain, ivory, and chocolate—were products of the international trade in luxury goods that was well developed by the beginning of the eighteenth century, and that trade appears around the pot’s circumference. Its subject is ships landing at a harbor and unloading goods to be brought to shore. The artist represents several trade galleons, which were used for long-distance travel across oceans, as they transfer their goods onto small boats that completed the voyage to land. A tollhouse tower is also visible, as is a city in the distance. Groups of men in European dress converse with others in clothing that suggests Middle Eastern origins. The figures gesture toward the packages’ destinations as we seem to catch them in a moment of haggling over prices. It is an unashamedly commercial subject, one that pictorializes the procedures required to bring luxury goods to Europe. Such subjects are common in eighteenth-century European art, but the story told here gains something from the porcelain that forms the ground for this image. One must imagine this scene of transoceanic trade being apprehended as part of encountering the materiality of this specific object. Here, porcelain draws attention to itself even as it asks to be comprehended as background to a representation. As an imaginary user would handle this pot (and, presumably, porcelain cups into which they would pour the chocolate), they would come into direct contact with the porcelain of its body and the ivory of its handle. At the moment they did so, they would catch peripheral glimpses of chocolate’s arrival in Europe. The porcelain, chocolate, and ivory work together to create fleeting sensory stimulation, a moment of difference from patterns of daily life. And given that chocolate’s pleasures are also multisensory and fleeting—flavor and aroma, notably—the beverage works with them to emphasize that moment of escape. There is thus an oscillation between materiality and representation built into this object’s design, specifically in how it triggers the senses.

Issues of distance and presence also emerge from this object and its decoration. Great geographical distances are in fact involved in the histories of porcelain, ivory, and chocolate, but this object collapses those distances and aestheticizes them through what I would call its presence effect. This is a term I derive from the thinking of Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, who describes it as an inexpressible sensation of immediacy and tangibility that certain works of art generate.[15] The presence effect triggers a feeling of closeness that comes from an activation of the senses. Porcelain’s materiality produces precisely this effect, particularly as it combines with other sensory experiences at the moment this chocolate pot is handled. What I would emphasize is that this presence effect combines in the Walters chocolate pot with pictorial indicators of distance. The two coexist in the object; it oscillates between referring to the faraway and confirming immediacy, but it is the immediacy of this object that is most strikingly conveyed through its materiality. An oil painting could have also reproduced this scene, but its canvas or wood surface would have carried none of porcelain’s material associations, and none of its haptic materiality. The chocolate pot brings porcelain’s materiality into insistent awareness through both visual and tactile means, and both directly through porcelain itself and by association with the other materials encountered in the moment of pouring chocolate.

We can also note that the object’s materiality in this case contradicts what the subject shows, since by 1725 porcelain was no longer exclusively brought to Europe through international trade. It was made domestically, at least in Saxony, so that the chocolate pot’s materiality toys with aspects of the scene’s pictorial veracity. Perceptive viewers will also notice that the porcelain used for the base of the pot’s handle, to which the ivory is attached, is decorated entirely differently from that of the body and lid of the vessel. It is adorned with a more conventional floral design similar to those seen on other objects; it also creates within this single object a variegated decorative experience that evokes a much broader realm of porcelain products, be they European or Asian, rare luxury products or more commonly available ceramics. Minimized in the pot’s decoration is the direct evocation of the porcelain’s East Asian origins, but one instance where it might be possible to see that is in the guardian lion/lapdog atop its lid. Yet there too transcultural blending is implied in the figure’s likeness to both Chinese and European animal imagery. The lid’s decoration further evokes these themes, but less precisely. One again sees European ships and port cities, and human beings at the moment of trade, with the non-European East signaled through the tents set up by traders at their ports of call.

Meissen Porcelain Manufactory, Teapot, 1724–25, porcelain with glaze. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Gift of Kenneth S. Battye, 2007, acc. no. 48.2781

Similar dynamics to those I have traced through the chocolate pot recur in many other eighteenth-century porcelain objects. To illustrate this, let us look at a second vessel in the Walters collection: a teapot (fig. 4). It bears the underglaze blue mark “KPM” (Königliche Porzellan Manufaktur), which was used to distinguish objects decorated at the Meissen royal factory from those decorated by Hausmaler, independent workers to whom objects would be farmed out for decoration. The teapot is an exceptionally fine example of gilding on porcelain, with complex rococo frames and arabesques winding their way across its surface. The pictures within this ornament are compositions in grisaille (gray tones), which combines with the gold, purple, and red of the arabesques to create an elegant palette of colors. The subjects superficially resemble those found on the chocolate pot. One of the two scenes represents a harbor. Once more, small boats bring packages to shore, while in the distance can be seen the ships that brought these goods across oceans to this destination. Yet again we see a tollhouse, beside which is an arched gate leading into a small, presumably European, town. In the teapot’s second scene, commerce remains the theme, but we find an interesting modulation of this subject. It depicts a European village, and men wearing wide-brimmed hats carry bags and bring their horses to water as a barge approaches the shore. From this scene of familiar everyday marketing, we are suddenly transported to a landscape with high arched mountains shown in the distance, behind which rises a prominent sun that shoots rays across the sky and onto the water. There are multiple ways to interpret this, but all would indicate that this is geographical fantasy. Referenced in the distance is the East in a broad sense—referred to poetically in German as Morgenland—and what we see here is its imaginary relationship to parts of the world more familiar to the European Meissen artists and consumers. That relationship is also borne out in a series of associations across and within the object: the ornamental abundance delineated across its surface, and the tea intended to be brewed inside it. Thus, the teapot presents a pictorial and material objectification of Europe’s relationship to the rest of the world.[16] The teapot leaves out the non-European people who are part of the story of European tea consumption; their presence is referenced only as the distant imaginary natural wonder. But in common with the chocolate pot, there are mixed associations between Asia, Europe, sight, touch, and the other facets that constitute this object’s materiality.

Meissen Porcelain Manufactory, Beaker Vase, ca. 1713–20, hard paste porcelain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The George B. McClellan Collection, Gift of Mrs. George B. McClellan, 1941, acc. no. 42.205.26

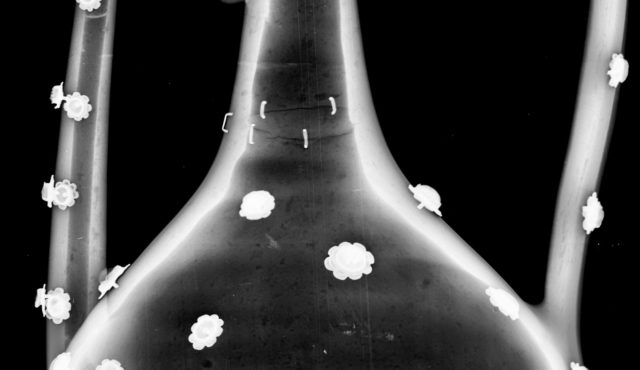

Although one finds similar subjects on vases from other European manufactories, there was reason for Meissen to pay special attention to these combinatory associations and build them into their designs. This should come as no surprise, given Meissen’s primacy in creating the European matrix of production for porcelain objects. But it has not been emphasized enough that Meissen’s designs often enable the specific material characteristics of porcelain to be prominent. One of the earliest hard-paste porcelain objects the Meissen manufactory produced is a vase now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 5). It has the shine and the whiteness found in the Walters pots, but in contrast to them is formed rather thickly. This emulates the export porcelain made in China for European consumption that was likewise dense in construction, although of course the variation in types and end results was great. When Meissen artists began to copy Chinese designs, they often did so while thinning the porcelain precisely to emphasize its material qualities, namely lightness and translucency. An illustrative object at the Walters is a blanc de chine cup dating from about 1730 that resembles the Metropolitan vase in a superficial way, but the porcelain is actually more finely molded and delicate (fig. 6).That change in density enables the cup’s material qualities to become more apparent. It should be noted that other porcelain innovations from the period directed its materiality to different aesthetic ends. Sèvres favored solid ground colors that contrast with the white of porcelain, enlivening the object’s surface with expanses of color in contrast to the decoration of the Meissen pots just discussed. Take for example a Sèvres bleu nouveau potpourri vase in the Walters collection dating from 1764, which like the Meissen specimens also includes a harbor scene (fig. 7). Yet, how unlike the Meissen examples this French vase is. The material’s whiteness is masked in order to show off the technical innovation of the evenly applied dark blue color. Certainly the whiteness of porcelain contributes to the luminescent glow of the vase’s blue surfaces, since the white base adds a luster that intensifies the blue pigment placed on it. But it is blue, and not white, that registers as the object’s primary color. Perhaps, as porcelain made domestically became more common in eighteenth-century Europe, some of the distinctiveness associated with its whiteness was lost and its meaning changed, which then put pressure on manufacturers to emphasize innovations in color. However one understands this change, the Sèvres vase engages in an entirely different sort of materiality, and those who owned and appreciated it likely did so from a different mindset than those who confronted the Meissen pots from forty years earlier.

Meissen Porcelain Manufactory, Cup with Raised Prunus Blossoms, 1725–30, hard paste porcelain with glaze. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Bequest of Henry Walters, 1931, acc. no. 48.1450

That observation about how porcelain was sensed over time brings us to one of the most appealing porcelain sets in the Walters Art Museum—a sculptural group of five objects that makes porcelain’s materiality and its apprehension by the senses the subject of philosophical reflection. They are a set of allegorical figures that represent the five senses. Attributed to the famed porcelain modeler Johann Joachim Kändler (1706‒1775), these small-scale sculptures date from between 1733 and 1745; each allegorical, female figure represents a sense and is shown with accompanying attributes and animals. Figural groups such as this were common and much in demand to adorn dining tables, fireplace mantles, or shelves. Subjects that lent themselves to the creation of sets like this include the four continents, and the four ages of man; in general, they gave the modeler the opportunity to explore similarity and difference across closely related figures. In the case of the Five Senses, we find more than just diversity within sameness; we find a moment where the medium of porcelain comments on perception. While allegory is the visual language employed, the figures enable porcelain to become a medium of multisensory contemplation.

Each of the five figures comments on the sense’s function. Let us look at them each in turn. The figure of Sound is a musician, shown singing, and accompanying herself on a lute (fig. 8). There is sheet music at her feet, which bears the word aria (Italian for a song or air), and the putto beside her sings along while cupping his ear. Into this scene of merry music-making, the artist has inserted a somewhat more sinister tone—namely, sounds associated with the hunt. We perceive these through the hunting horn included at the figure’s feet and the deer beside her. If sounds can be associated with pleasant music, they also are evocative of power and, through hunting, with taste. This reference to taste brings into play the first of many synesthetic moments among the five figures, suggesting the ways in which one sense can stimulate another.

The other figures in the set elaborate on this play of perceptual transferal. The most complex of the five is Sight, who looks through a small telescope and holds a mirror (fig. 9). The implication here is that optical instruments enable us to see things that are very close and also very distant, therefore conveying the great power of eyesight. It was Aristotle who first described vision as “the most excellent and most noble of the senses,” a statement which set up a dominance that sight has held in the Western philosophical tradition ever since. The accompanying putto in this case holds a lantern, and there are multiple small lenses strewn about the sculpture’s base, as well as a second, slightly larger telescope. The accompanying animal is this time an eagle, the keenest of avian hunters. The term eagle-eyed comes to mind, and indeed it was widely used in both eighteenth-century English and German (adleräugig). The eagle also conveys social power, as it is a common symbol of European nobility.

If Kändler attributed less distinction to Smell (fig. 10) and Taste (fig. 11) it is because the discursive tradition of understanding the senses generally deemed them less complex than the other senses. Smell appears as a woman sniffing flowers, a perfume vase and censer at her side, while a putto picks buds from a plant, and a dog, an animal known for its sharp olfactory ability, sits beside them. Taste eats a piece of fruit; at her feet is a plate of food (possibly meat or fish), and a putto with a bowl of soup rests nearby. The relatively uncomplicated conceptualizations of taste and smell shown here would alter later in the eighteenth century, as philosophers devoted ever greater attention to these senses’ workings. This heightened attention would occur in tandem with the rise of the perfume industry in France and the formation of middle-class gourmet food culture across Europe. [17] However, Kändler’s Taste and Smell are still presented straightforwardly.

This brings us to Touch (fig. 12), and with this sense, both the tone and the implications of this exploration change. Unlike the other four figures, the allegorized woman does not appear to experience her sensory revelations joyfully. Rather, she is in distress, her mouth agape, her facial muscles tensed. This is because the parrot perched on her finger has taken a nip at her skin, while at the same moment, her canine companion chomps at her foot. To her side are two putti shown engaged in combat—one has overpowered the other through brute force and assaults the vanquished with his fists. Humorous, perhaps, but unpleasant nonetheless. Transformed as well is the respective body part, here a hand for touch, cleverly represented in the rococo base of the sculpture. In the other four figures, these are witty, even farcical, additions to their iconography: we find an eye, an ear, a nose, and a rather grotesque mouth to symbolize the body part associated with each sense. But in the place of these, we find on Touch something less pleasant: a crayfish pinching a distended finger with its claw. This makes clear that touch, as presented here, is primarily a negative sensation and allied to (indeed, often elided with) pain.

In an era known for its appreciation of sensuality and eroticism in the arts, it is surprising to find touch presented this way and not, for example, through the pleasing caresses of a lover, as a rococo painter like François Boucher or Jean-Honoré Fragonard might have done. Exactly who devised this shift in the Meissen figures is not precisely clear, but it has the effect of singling out Touch for special status. A large part of porcelain’s appeal was visual, but porcelain could also stimulate the other senses through association: vessels made of it held beverages like coffee, chocolate, and tea that enticed taste and smell with their flavors and aromas, and high-quality hard-paste porcelain has a distinctive audible ring to it when struck. Yet among the senses, it was porcelain’s effects on touch that most excited eighteenth-century collectors, because its tactility distinguished it decisively from more commonly encountered European ceramics. Kristel Smentek has noted that eighteenth-century French discussions of porcelain focused intently on the material’s tactility, so much so that connoisseurs developed a term to describe its effects on the collector: the tact flou, or vague touch, a concept that recognizes porcelain’s sensuality, but also identifies something about it as beyond easy comprehension.[18] It is the haptic cousin to another eighteenth-century French aesthetic premise, the je ne sais quoi, that indescribable something that makes a work of art great.[19] If a painting can be appealing because of its je ne sais quoi, then a porcelain object appeals because handling it triggers the tact flou, a haptic awareness of the material’s indescribable excellence. The Meissen figure confirms that special status by picturing touch on its own terms.

And yet that sensual appeal was also a potential danger, as this figure reminds us. Touch is more difficult to define or describe than either vision or hearing, and something about touch remains stubbornly individual, resisting definition in collective terms. Kändler’s group invites a comparison of the different ways in which the medium of porcelain relates to the senses, but from this, touch emerges as the most problematic, even as it is also possibly the most appealing. Representing touch in this way marks a change with important implications for understanding porcelain’s materiality, since Enlightenment philosophers placed this particular sense under extensive scrutiny, devoting particular attention to the ways in which touch contributed to knowledge about the physical world.[20] The beauty of the porcelain surface would seem to contradict the idea of touch as painful, since it is seductive in its glossy smoothness. Yet we all have experienced physical pain, and that knowledge is evoked directly in what this figure shows.

With that in mind, we can return to Miller’s idea of materiality. We might propose that this figurine invites doubt about how touch conveys knowledge to the individual who encounters it. Human knowledge about the world enabled this porcelain sculpture to be made, and the beholder to philosophize about sensation and knowledge in ways that illuminate the significance of touch, but it also reveals the sense’s visceral character, the directness with which it produces sensations, and the way in which these sensations are not always enjoyable. Touch is therefore a dangerous sense. An unpleasant smell or shocking sight might trouble the mind, but a painful physical sensation is not quickly overcome and, arguably, literally hurts more. This unpleasant idea of touch contradicts the pleasing tactile qualities of porcelain; it thereby introduces a contradiction that may cause the observer to question and even distrust their senses. The Meissen figure of Touch challenges the elite consumer to imagine the danger that lurks beneath the pleasure of apprehending this porcelain object. Pondering that, we might then say that the Meissen quintet produces (in Miller’s sense) consumers more attuned to the multivalency of sensory experience, even as they are perhaps pushed to regard sensual knowledge with skepticism.

This close consideration of Meissen porcelains at the Walters Art Museum has raised a number of critical issues about the relationship between ceramics and materiality. Materiality has often been understood as something upon which significance is built through other means, usually pictorial representation. My analysis has suggested that materiality can intertwine with imagery to create layered constructions of meaning, and moreover, that these constructions offer clues to the mindsets of those who created and first appreciated them. Porcelain is filled with contradictions too: each object I have discussed both creates meaning and counteracts it at the same time, in what should be understood as a typically rococo effect. One takeaway of our investigation is that the visual and material are related aspects of every artistic construction, the opposite sides of every artistic coin, so to speak. Such a claim would not be out of place in a discussion of contemporary ceramics, and if there is an additional point to be made, it is that Meissen porcelains, seemingly so different from contemporary pottery, actually engage concepts similar to those that animate ceramic art today. Contemporary ceramics and Meissen objects traverse the overlapping discursive terrains of identity, geography, and physicality, and they do so by toying with the beholder’s perceptions of what they see and, in some cases, touch. By theorizing materiality in eighteenth-century Meissen porcelain, we can come closer to recognizing the continuity between current artistic concerns and those of the past, even as we appreciate anew the historical difference that Meissen porcelain forever places at the forefront of our experience.

I would like to thank Joanna Gohmann and Eleanor Hughes for inviting me to the workshop out of which this essay grew, its participants for a stimulating discussion, and the staff of the Walters Art Museum for their warm welcome and stewardship of this essay to publication.

[1] A recent endeavor to do just this is Paul Greenhalgh, Ceramic, Art, and Civilisation (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021), 18–63.

[2] The material turn dates from around 2000 and gained prominence after the publication of Bill Brown’s A Sense of Things: The Object Matter of American Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), which brought the idea of “thing theory” to literary studies. There are important predecessors in other disciplines, notably anthropology and archaeology, where material culture has formed a sustained critical interest for decades. For this broader history, see Dan Hicks, “The Material-Cultural Turn: Event and Effect,” in The Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Studies, ed Dan Hicks and Mary C. Beaudry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 25–98.

[3] Jules David Prown, “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method,” Winterthur Portfolio 17.1 (Spring 1982): 1–19.

[4] Michael Yonan, “The Suppression of Materiality in Anglo-American Art-Historical Writing,” in The Challenge of the Object/Die Herausforderung des Objekts, ed. Georg Ulrich Großmann and Petra Krutisch (Nuremberg: Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, 2013), 1:63–66. On the question of how to define a thing, there can be no easy answer, but for one perspective see Martin Heidegger, “The Thing,” in The Object Reader, ed. Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins (London: Routledge, 2009), 113–23.

[5] Daniel Miller, “Materiality: An Introduction,” in Materiality, ed. Daniel Miller (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 10.

[6] In particular, Miller engages with G. W. F. Hegel, Michel Foucault, and Georg Simmel, among others.

[7] Miller, “Materiality,” 4.

[8] On the developments leading to the fruition of true European porcelain, see Julie Emerson, Jennifer Chen, and Mimi Gardner Cates, Porcelain Stories: From China to Europe (Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, in conjunction with University of Washington Press, 2000), 24–34 and 153–93.

[9] Robert Finlay, The Pilgrim Art: Cultures of Porcelain in World History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 5–7.

[10] Jeffrey Munger, European Porcelain in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018), 4–5.

[11] For the significance of the soft- and hard-paste distinction to French art and science, see Christine A. Jones, Shapely Bodies: The Image of Porcelain in Eighteenth-Century France (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2013), chap. 2 and 6.

[12] Adrienne L. Childs, “Sugar Boxes and Blackamoors: Ornamental Blackness in Early Meissen Porcelain,” in The Cultural Aesthetics of Eighteenth-Century Porcelain, ed. Alden Cavanaugh and Michael Yonan (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010), 159–78.

[13] I refer here to the trois crayons technique favored by Antoine Watteau, among other French and Italian draughtsmen. See Alan Wintermute, Watteau and His World: French Drawing from 1700 to 1750 (New York: American Federation of the Arts, 1999), 25–26; and JoLynn Edwards, “Watteau Drawings: Artful and Natural,” in Antoine Watteau: Perspectives on the Artist and the Culture of his Time, ed. Mary D. Sheriff (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2006), 43.

[14] Mimi Hellman, “The Decorated Flame: Firedogs and the Tensions of the Hearth,” in Taking Shape: Finding Sculpture in the Decorative Arts, ed. Martina Droth (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2009), 176–85.

[15] Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004), 54–64.

[16] Similar acts of framing and distancing occurred concurrently in Asian art. An eight-panel screen painting in the National Museum, Beijing, made possibly by the Kangxi-era court painter Jiao Bingzhen (act. 1669–1726), includes multiple framing and enclosing techniques that create the sensation of apprehending a distant culture through a framed pictorial space. See Richard Vinograd, “Hybrid Spaces of Encounter in the Qing Era,” in Qing Encounters: Artistic Exchanges between China and the West, ed. Petra ten-Doesschate Chu and Ning Ding (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2015), 22–23.

[17] For which see Food History: A Feast of the Senses in Europe, 1750 to the Present, ed. Sylvie Vabre, Martin Breugel, and Peter J. Atkins (London: Routledge, 2021), with additional bibliography.

[18] Kristel Smentek, “Global Circulations, Local Transformations: Objects and Cultural Encounter in the Eighteenth Century,” in Qing Encounters, 49–50.

[19] On the je ne sais quoi, see Mary D. Sheriff, Fragonard: Art and Eroticism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 121–22.

[20] Most prominently in the Abbé de Condillac’s Traité des Sensations (1754), but touch is traceable throughout much of eighteenth-century philosophy to Immanuel Kant.