Palmesel, Germany (Franconia), ca. 1350–1400, wood and paint with gilding, 37 13/16 × 13 3/8 × 32 5/16 in. (96 × 34 × 82 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum purchase with funds provided by the Loretta Ver Valen Acquisition Fund, 2019, acc. no. 61.361

The celebration of Easter, the day that Christians believe Jesus Christ rose from the grave (Resurrection) following his death on the cross (Crucifixion), was the most significant date in the medieval Christian calendar. In the New Testament of the Bible, all four of the biblical Gospels (accounts of the life and teachings of Christ) describe how Jesus arrived in Jerusalem on the Sunday before his Crucifixion. They describe Jesus riding on a donkey toward the city gates, his followers welcoming him as the savior by laying palm branches and clothing in his path.[1] This event is still celebrated today by Christians on Palm Sunday, when palm branches are distributed to congregation members and the priest processes into the church to musical accompaniment.

Modern-day palmesel processional in Tyrol, Austria. Image from Blog Innsbruck / W. Kraeutler.

Beginning around the year 1200, medieval Christian theology and devotion focused increasingly on Christ’s life on earth and his humanity, rather than his otherworldly, divine aspects. According to a practice known as affective devotion developed at this time, the faithful were expected to meditate on events from his life and the lives of other sacred figures, such as the Virgin Mary (Jesus’s mother), martyrs, and saints, to attempt to experience their joy, sorrow, and pain empathetically. As a result of this theological teaching, images of Christ and the saints became more naturalistic and emphasized their miraculous acts and horrific martyrdoms. It was around this time, probably in the tenth century, that the earliest wood sculptures appear depicting Christ astride a donkey, with the ensemble mounted on a wheeled cart. This so-called Palmesel (palm donkey) was a type of mobile and performative sculpture commonly used in German-speaking lands from the thirteenth to sixteenth century (fig. 1).[2] A Palmesel could be the centerpiece of a Palm Sunday procession through the streets around a parish church, where Christ’s entry into Jerusalem would be acted out by the clergy (those ordained for religious duties) and worshippers with the sculpture representing Jesus. Unlike many ritual items handled only by the clergy, such as chalices, patens, and manuscripts containing the Christian liturgy, Palmesels were processed through the streets around parish churches filled by crowds of the faithful who could physically touch them. These sculptures sometimes traveled from one church to another, and they were often escorted by children (fig. 2).[3] Re-enacting the events of Palm Sunday with a mobile sculpture of Christ vivified the biblical narrative of his Passion and allowed the laypeople of a parish community to take part in an immersive experience of a significant event from Christ’s life in their own time and place.

The Walters Art Museum recently acquired one of the earliest surviving Palmesels (fig. 3). In this engaging sculpture, Christ sits triumphant atop a donkey, gazing forward and raising his right hand in a gesture of blessing. His elaborate robes are draped to suggest the solid form of his body beneath them, and they are richly colored in red and green as well as gold, lending the figure a regal air. Jesus’s face is beautifully and smoothly finished to convey his death in his prime, while details such as his pronounced eyelids and brow ridges focus the viewer’s attention on the steady gaze, signaling a stoic acceptance of his impending death on the cross (fig. 4). The animal he rides is sensitively rendered, even endearing, with soft features and downcast eyes . Christ’s choice to arrive on a lowly donkey, most often used as a beast of burden to carry heavy loads, symbolizes his humanity and modesty. In the biblical account of the Entry into Jerusalem, Jesus instructs his followers to find a donkey for him to ride, fulfilling Old Testament scripture about the coming of the Messiah: “Behold thy king cometh to thee, meek, and sitting upon an ass.” [4]

On the reverse of the sculpture, a square cavity in Christ’s back, concealed by a wood cover, was probably used to hold a relic (fig. 5). Compartments of this shape and with a similar placement appear in various genres of medieval wood sculpture used in a Christian context, for example, the corpus, or body, of Jesus in crucifixes, and in figures of the Virgin Mary.[5] The insertion of a holy relic into the Palmesel would have further sanctified it and enhanced its significance for early users.

Stylistically, and in terms of scale, this Palmesel can be dated to the second half of the fourteenth century. The figure’s heavy, looping drapery and the stable, almost motionless, poses of Christ and the donkey recall a Palmesel in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, which dates to about 1370–80 (fig. 6).[6] While examples from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are often close to life-size, this earlier example is approximately half that of life. This smaller scale would have facilitated its movement by children in a mountainous Alpine landscape and would have increased its approachability allowing for a more intimate relationship between the viewer and the sculpture.[7]

Fig. 6

Palmesel, Germany (Franconia), ca. 1370–80, alderwood, willow, and paint, 67 15/16 × 24 3/16 × 66 9/16 in. (172.5 × 61.5 × 169 cm). Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, acc. no. PI.O.153

Although it was a popular genre of sculpture in Europe’s late Middle Ages, fewer than 175 complete or partial medieval Palmesels are known to survive.[8] Many are still on display and in use in churches in the German-speaking countries of Germany, Switzerland, and Austria.[9] Others were decommissioned from use and acquired by prominent museums, including the Musée de Cluny, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the example from the Germanisches Nationalmuseum cited above.[10] The Walters Art Museum joins only three other American museums that own a Palmesel: the Met Cloisters in New York, the Detroit Institute of Arts, and the Chazen Museum of Art at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.[11] The Walters’ example is the earliest by at least fifty years, and also the smallest. The other examples in American museum collections all date to the fifteenth century and are close to life-size. The acquisition of this rare surviving example represents the first instance of larger-scale medieval kinetic, or movable, sculpture in the Walters’ collection.

A very few examples of Palmesels are known to be in private hands.[12] While the Walters Palmesel is largely unpublished, likely because it was in private hands, an early record of its provenance appears in the 1951 publication Die Sammlung Hubert Lüttgens, Aachen.[13] In his introduction, Lüttgens states that he purchased both the home and art collection of the Klausener family before World War II in 1939. The Klauseners were a prominent family of architects and builders in Burtscheid, Germany, just outside of Aachen. They shaped the architectural landscape of the town, and some members were leaders in the local government.[14] The subsequent 1955 catalogue of Lüttgens’s collection includes a photograph of the Palmesel in situ at the family home, prominently placed at the foot of the grand staircase in the entrance hall.[15] The Palmesel remained in the Lüttgens family, until it was purchased by Sam Fogg, London, from Auktionshaus Lempertz, Cologne, on May 12, 2012. The Palmesel made its American debut when it appeared in Sam Fogg’s exhibition, Wonders of the Medieval World, at Richard L. Feigen & Co. in New York in 2014.

Technical Examination

Physical evidence suggests that Palmesels experienced significant wear—wheeled over dirt roads and cobblestone streets, jostled and touched by parishioners along the way—which is supported by written records. Contemporary accounts document their repeated repair and replacement over time, and existing examples show evidence of these interventions: refurbished joinery, multiple coats of paint, and even replacement of the entire donkey.[16] Considering that some Palmesels continued to be used for centuries after their creation, it can be difficult to differentiate repairs during their liturgical use from later restorations.

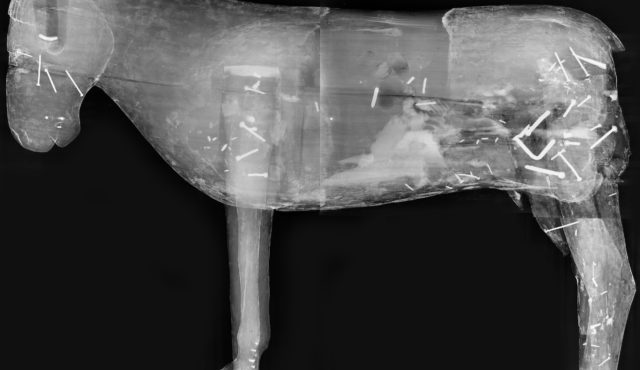

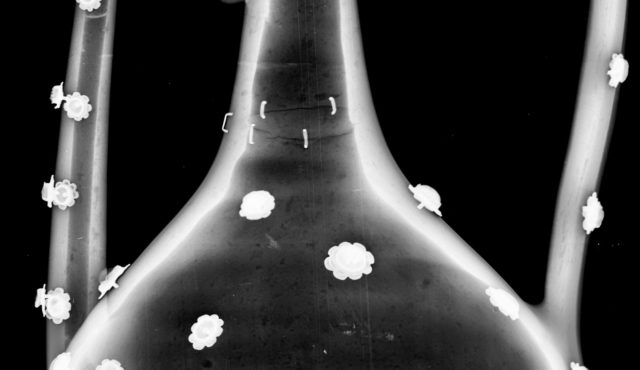

The Walters’ Palmesel shows signs of use and repair consistent with its function. Shortly prior to its acquisition by the Walters, fills, paint layers, and coatings considered later restorations were removed. This conservation treatment significantly altered the sculpture’s appearance and revealed damage and repairs that had occurred over the many years of its use as a processional object.[17] The visual evidence of these changes, combined with new information from X-ray radiography, allows for a better understanding of the Palmesel’s history and changes over time.[18]

The overall form of the Walters’ Palmesel remains largely in its original state; some minor elements were lost but can be gleaned from material evidence and comparable examples. Significant repairs were made to Christ’s arms and the donkey’s legs, evidenced by additional pegged and nailed elements and interruptions in the overall paint layers. Once present but now missing are Christ’s left hand, feet, and the back of his head. Additional elements are suggested through embedded nails revealed during X-ray radiography. Christ once likely held reins in his missing left hand that attached to the sides of the donkey’s snout or a now missing bridle, evidenced by embedded nails near the donkey’s mouth. Additionally, the sculpture was also probably once adorned with textiles, indicated by embedded nails in the cloak’s wood clasp.

Detail of back of head

The missing section of wood on the back of Christ’s head is less obviously explained. The conservation treatment in 2018, prior to the Walters’ acquisition, removed a section of wood that was considered a later restoration. Under this fragment was a flat, largely unpainted surface with numerous holes, suggesting the presence of a previous nailed attachment, now lost (fig. 7). The loss suggests a halo, perhaps represented by a flattened disk, was once present, as sometimes seen in painting and sculpture of the time. A small number of other Palmesels feature Christ figures with crowns or protruding rays at the head suggesting that there is some tradition of head adornment.[19] In addition to these missing elements, sculptures of this type typically feature Jesus’s bare feet hanging below the tunic. Although not present in the Walters’ example, X-ray radiography revealed filled holes on the underside of the draped legs, indicating where separately carved feet were once attached.

Additional losses and repairs have occurred over the lifetime of the Palmesel, probably attributable to damage during use but possibly also the result of environmental fluctuations, wood deterioration, and insect damage. Jesus and the donkey were each originally carved from a single large piece of wood, with other elements, such as Jesus’s arms and the donkey’s legs, tail, and ears, being constructed from other pieces of wood and attached with dowels. The largest sections have both experienced dimensional changes—expansion and contraction of the wood due to fluctuations in temperature and humidity—that caused the detachment of parts such as the entire proper left side and leg of Jesus as well as the snout of the donkey; both were reattached with nails. These sections were once again removed, reinforced, and restored as recently as 2018.

The most significant repairs to Christ involve the arms, each of the lower sections were probably carved from a separate piece of wood and attached to the body, but subsequent repairs have masked evidence of this original construction (fig. 8). The right arm is in multiple fragments that have been reattached using dowels, nails, and adhesive at various times. It is unclear which of these pieces are later additions versus reused original parts. A comparison of the two arms shows stylistic differences that could be due to repair or replacement. The loose sleeve on Jesus’s right arm is carved with more detail, showing a folded cuff with an exposed lining that rests at the wrist, while the left sleeve terminates in a flat surface without the same attention to carved details. If this is the original location of the hand on the left arm, the forearm would have been much shorter as the elbow does not project far behind the torso. This indicates that the arm was probably damaged and shortened with a new or reused hand attached to the cut surface. This could explain the lack of carved detail and the differences in the arm proportions and cuffs.

As is seen in other examples, the donkey has sustained extensive damage and been repaired in multiple campaigns (fig. 9). The ears are modern replacements that fit into heavily damaged sockets carved into the head of the donkey. The tail has suffered a similar fate and is spliced with a newer piece of wood.[20] The poor condition of the legs, perhaps the most vulnerable part of the sculpture, speaks to many years of use and repair. The legs are inset into cavities carved within the donkey’s torso, causing considerable wear to the surrounding wood, as they moved within the cavities when the sculpture was jostled in processions. These areas are weak and have been reinforced with additional stabilizing pieces of wood. Dowels and nails from multiple repair campaigns are visible in X-ray radiographs. It is possible that all or some of the legs were replaced at some point in one or multiple campaigns, and the front proper left leg, with its less naturalistic carving, is distinct from the others. Three legs are set into the body and carved to more or less follow the adjacent contours of the torso to make them roughly appear as one piece but the front proper left leg is rounded at the top and differs in shape from the recessed cavity where it is inset into the torso. Another peculiarity is that the front legs both have hooves, while the rear legs do not.[21] It is unlikely that the extant rear legs originally incorporated hooves, as, if hooves were present, the legs would be overly long, significantly changing the posture and proportions of the donkey’s body. This lack of rear hooves is perplexing and could possibly be explained by the various campaigns of repairs and replacements that have occurred. The authors have not seen any other examples of Palmesels with unhooved rear feet. The base of the repaired rear leg was also previously inset into a board, which acted as a base for its display at a more recent date, most likely in the twentieth century.[22] This board was removed and replaced with a modern display cart just prior to the Palmesel’s acquisition by the Walters.[23]

There is evidence that the two major sculptural elements of Christ and the donkey were once doweled together, helping to secure, but probably not fully stabilize, and lock in the two elements when moved. It is possible that the currently visible gap between the two figures was originally filled with plaster (now removed) and concealed with paint in the original construction. It is also possible that the entire donkey was replaced at some point since they do not fit tightly together. However when disassembled, the portion of the donkey’s back underneath Jesus is unpainted and closely follows the outline of the figure, including an area of drapery that is now missing. This evidence together with the comparable condition and history of repairs which unite the two sections indicate that they have been together for a considerable amount of time.

Close visual examination, a study of previous documentation, and X-ray radiography have shed light on the many alterations that have occurred to the Palmesel as both a liturgical object and in the hands of private collectors. Future study of the paint layers as well as further comparative and documentary research will undoubtedly shed light on not only the sequence and history of repairs described above, but also the valuable role this sculpture played over centuries of use.

Conclusion

Medieval art, particularly sculpture, is often perceived as static; however, Palmesels demonstrate that it could also be dynamic and theatrical. The many layers of paint and campaigns of repair consistent among surviving Palmesels speak to their continued use and value over many centuries. Unlike many objects from the Middle Ages seen in museum collections, the Palmesel would have been accessible not just to the wealthy elite and the clergy but to a broader swath of society. It is a significant and uncommon piece that demonstrates a high level of craftsmanship lavished on an object used in everyday life. The Palmesel is evidence of the enduring importance of the dramatic performance of a central biblical event, a phenomenon that can now be presented in the galleries of the Walters Art Museum.

[1] (Matthew 21:1–11; Mark 11:1–11; Luke 19:28–44; John 12:12–19). The Gospel of Matthew (Douay-Reims 1899 American Version) describes the gathering of a donkey and its colt, the Gospels of Mark and Luke mention a colt, and the Gospel of John calls the animal an “ass’s colt.”

[2] One rare, surviving example dating to ca. 1055 is in the Forum Schweizer Geschichte Schwyz, Switzerland (LM-362). See https://sammlung.nationalmuseum.ch/de/list?searchText=palmesel&detailID=99196.

[3] For a detailed account of present-day Palmesel processions in Europe, see Max Harris, Christ on a Donkey: Palm Sunday, Triumphal Entries, and Blasphemous Pageants, Kalamazoo, MI: Arc Humanities Press, 2019, 207–26. Some modern-day Catholic churches, such as St. Joseph’s Monastery Parish in Baltimore, re-enact Christ’s entry into Jerusalem with the priest riding on a live donkey and accompanied by deacons, altar servers, and other parishioners. We are grateful to Ellen Hoobler for informing us about this local Palm Sunday celebration.

[4] (Matthew 21:5). In this New Testament passage, Christ quotes the language from Zechariah 9:9, a book in the Old Testament.

[5] See Gerhard Schneider, “Zur Holzbearbeitung der Kölner Skulptur vom. 11. bis zum Ende des 14. Jahrhunderts,” in Schnütgen-Museum, Die Holzskulpturen des Mittelalters (1000–1400), ed. Ulrike Bergmann (Cologne: Anton Legner, 1989), 73.

[6] See https://objektkatalog.gnm.de/wisski/navigate/108293/view.

[7] See object report from Sam Fogg, London.

[8] This tally is based upon the work of Marijke Broekaert and Patrick Valvekens, plus known examples in private collections. See “De palmezel: oorsprong, iconografie en geografische verspreidung,” in De palmezelprocessie: Een (on)bekend West-Europees fenomeen?, eds. Luck Knapen and Patrick Valvekens (Leeuven: Peeters, 2006), 113–58. Many Palmesels were likely destroyed during the Reformation, see Christian von Burg, “‘Das bildt vnsers Herren ab dem esel geschlagen.’ Der Palmesel in den Riten der Zerstörung,” Historische Zeitschrift 33 (2002): 117–41.

[9] The Palmesel sculpture genre also appears in France, Poland, Spain, and Italy, but many of these differ significantly in their sculptural style from the Germanic works. At least some Spanish examples were carried in procession on a litter, and therefore were not mounted on carts.

[10] Baden-Württemberg, Germany, last quarter fifteenth century (122 × 100 × 44 cm), Musée de Cluny, Paris, Cl. 23799[https://www.musee-moyenage.fr/collection/oeuvre/christ-des-rameaux.html]; Possibly Ulm, Germany, ca. 1480 (147.4 × 47.8 × 133.5 cm), Victoria and Albert Museum, London, A.1030-1910 [http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O73843/christ-on-an-ass-statue-unknown/]; see note 9.

[11] Franconia, Germany, fifteenth century (61 1/2 x 23 3/4 x 54 1/2 in.), The Met Cloisters, 55.24[https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/471557]; Christofel Langeisen (German), between 1480 and 1490 (56 1/2 × 16 × 43 1/2 in.), Detroit Institute of Arts, 57.97 [https://www.dia.org/art/collection/object/christ-entering-jerusalem-back-donkey-51735]; Austria, ca. 1450 (61×56 ¾ × 19 ¾ in.), Chazen Museum of Art, 1977.2 [http://embarkkiosk.chazen.wisc.edu/Obj19873?sid=70088&x=2740697].We are grateful to Maria Saffiotti Dale for bringing the Chazen Museum Palmesel to our attention.

[12] One example was sold in the 1990s to a private collection in Germany through Julius Böhler. We thank Florian Eitle-Böhler for bringing this example to our attention.

[13] Ernst Günther Grimme, Die Sammlung Hubert Lüttgens Aachen (Hamm: Breer & Thiemann Buchdruckerei, 1951), 13, 14, 36, 38, figs. 5, 23.

[14] For the Klausener family and their architectural impact, see Rosa-Marita Schrouff, Das Porträt von Henry Lambertz: Gründer der Aachener Printen-Fabrik. Meine Familien-Chronik in Bildern (Berlin: epubli, 2013), 323; and Eduard Philipp Arnold, Das alt Aachener Wohnhaus (Aachen: Aachener Geschichtsverein, 1930).

[15] Haus Lüttgens, Alt-Aachener Wohnkultur: Ein Rundgang durch ein altes Aachener Haus im Wohnstil des 18. Jahrhunderts(Aachen: M. Brimberg Druck und Verlagsgesellschaft, 1955), 9, 27, 81.

[16] Elizabeth Lipsmeyer, “Devotion and Decorum: Intention and Quality in Medieval German Sculpture,” Gesta 34, no. 1 (1995): 24. Harris, Christ on a Donkey, 207. Manon Joubert, “Study and Restoration of the Christ of the Palm Branches of the Museum of the Notre-Dame de Strasbourg,” CeROArt EGG 4 (2014), https://doi.org/10.4000/ceroart.4010. See also the extensive study of the Palmesel from Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany, and the six campaigns of restoration it underwent over its lifetime, Der Palmesel: Geschichte, Kult und Kunst, exh. cat. (Schwäbisch Gmünd: Museum für Natur & Stadtkultur, 2000), esp. 27–41.

[17] Condition Assessment report, Colin Bowles Ltd, August 2, 2018.

[18] Computed X-ray radiography was performed with a Varian X-ray tube with a Polaris MC-250 control system, GE CR50P plate scanner, and Rhythm software. X-ray radiographs were edited in Adobe Photoshop and with Lucis Pro.

[19] Examples include the Christ Des Rameaux in the collection of the Musée de Cluny (inv. no. CL.23799) dating from the late fifteenth century and with protruding head rays [https://www.musee-moyenage.fr/collection/oeuvre/christ-des-rameaux.html]; the Palmezel met Christus in the collection of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe (inv. no. 0382), dating from the early fourteenth century, with an attached metal crown [https://collectie.rijksmuseumtwenthe.nl/zoeken-in-de-collectie/detail/id/b95e1865-f2c5-5a9c-a5b0-55ae7041fb87]; and the Christ Riding a Donkey in the collection of the Chazen Museum of Art (acc. no. 1977.2) dating from ca. 1450 and with an integrated crown [http://embarkkiosk.chazen.wisc.edu/Obj19873?sid=70088&x=2740697].

[20] The ear and tail repairs were noted in the pre-acquisition treatment report to be twentieth-century replacements and repairs. Although not specifically discussed in the report, treatment photographs show that the ears and tail insert were stripped of paint. This assessment of their age was likely based on the condition of the wood and a simpler paint scheme than the rest of the sculpture; however, the tail section has more than one hole indicating that it was possibly attached multiple times. See Condition Assessment report, Colin Bowles Ltd, August 2, 2018.

[21] The rear proper right leg has been repaired, obscuring where a hoof could have been, but neither leg has the appearance of once having a hoof.

[22] A photo of the Palemsel prior to the removal of the board can be seen at the Auktionshaus Lempertz website: https://www.lempertz.com/en/catalogues/lot/995-1/1367.html.

[23] Condition Assessment report, Colin Bowles Ltd, August 2, 2018.