The Walters’ pair of Vases à tête d’éléphant (acc. nos. 48.1796 and 48.1797), or elephant-head vases, are spectacular examples of the innovative and artistic design that made the Sèvres Manufactory internationally famous (fig. 1). Designed by Jean-Claude Duplessis le Père (ca. 1695–1774) and manufactured between 1756 and 1762, elephant-head vases creatively combined the forms of a vase and candelabra.[1] These ornate, delicate porcelains were incredibly rare in the eighteenth century, and are even more so today: only twenty-two are known to survive.[2] The Walters’ examples are considered by many to be a set purchased in 1762 by Louis XV’s maîtresse-en-titre, or chief royal mistress, Madame de Pompadour (1721–1764).[3] They stand out from others with their chinoiserie painting by the famed Charles-Nicolas Dodin, unusually elaborate color scheme, and the absence of the typical candelabras.[4] This paper will specifically address some of the unusual features of these vases in light of a recent technical study that clarified the extent and history of restorations using examination and analysis, in conjunction with historic photographic documentation.

Joanna M. Gohmann, Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow at the Walters Art Museum (2016–19), raised the question in 2018 of the remarkable differences between the Walters’ vases and the other surviving Vases à tête d’éléphant. Struck by the absence of the candleholders or the corresponding sockets in the trunks, the lack of continuity in the color palette between the vase and pedestal, and an unusual painted feather pattern, she questioned if these inconsistencies were a part of their original design and attributable to the hybridity of European and Chinese design or historical modifications. With these questions in mind, a technical study of the vases was undertaken in 2019 using multiple methods of non-destructive examination and analysis including microscopy, ultraviolet radiation, computed X-ray radiography, and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy to better understand their condition and the extent of restoration. These methods coupled with the review of early photographs found by Gohmann have revealed how the Walters’ Vases à tête d’éléphant changed over time.

Detail of trunk (conservation documentation)

Elephant-head vases were among the more technically complex designs manufactured at Sèvres.[5] These ornate vases have flared and lobed rims with round bases set on squared pedestals with curled acanthus leaves for feet. Elephant heads protrude from the neck of each vase resting their upturned trunks on small handles at the shoulder. Although not the case with the Walters’ examples, each trunk typically had a squared socket that would receive a porcelain candleholder for either one or two candles, often missing or heavily restored in existing examples. Formed using pâte tendre, or soft-paste porcelain, the vases were likely wheel-thrown and mold-made.[6] Soft-paste porcelain, which was fired at a lower temperature than hard-paste porcelain used later in the decade, was known to be more prone to slumping and cracking during firing. These challenges likely factored into the changes Sèvres introduced to later examples of elephant-head vases in the course of their production. In addition to decorative adjustments to the vase such as changes to the strings of beads, small handles were added to the body under each elephant’s trunk, most likely to provide more support during firing.[7] Evidently, these changes did not also solve inherent structural vulnerabilities post-manufacture, as many examples have repaired trunks.

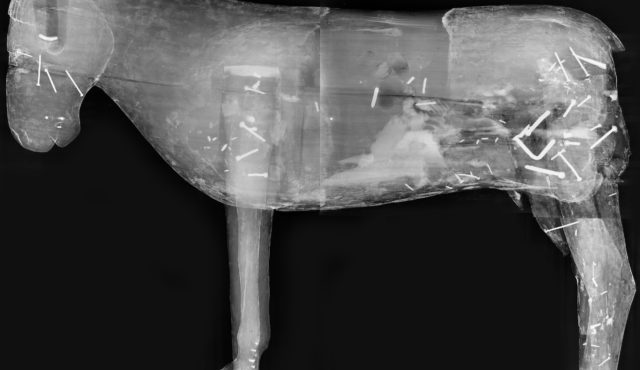

The Walters’ examples have beautifully rendered pink and fleshy trunk ends unlike those seen on other examples, which are flat and undecorated (fig. 2). Suspecting that they might be restored, the trunk ends were examined microscopically and using ultraviolet radiation. Surprisingly, there was no overpaint—later non-original paint covering the original surface—but ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence confirmed extensive overpaint in the middle of the trunks on both vases (fig. 3). X-ray radiography was used to look for evidence of filled and now hidden sockets for candle holders but instead showed that all four of the elephant trunks had actually been replaced with well-executed porcelain restorations with no sockets. The qualities of the porcelain and glaze between each section are different in the X-radiograph, confirming that these trunk ends are not from the original manufacture (fig. 3). The glazed and gilded replacements convincingly complete the trunk from the break points near the handles out to the tips, so that it is no longer apparent that they were originally designed to hold porcelain candleholders.[8] Associated with this damage, both handles on 48.1797 are also damaged, including the proper left which was once fully detached, and half of the eight tusks on the vases were reattached or replaced with some evidence of non-original interior support wires.

Three early photographs of the elephant vases are known to exist and are invaluable in understanding the timeline of changes to the vessels (fig. 4). The earliest known photograph of the vases, found in the publication A Description of the Works of Art Forming the Collection of Alfred de Rothschild, illustrates that the candleholders were absent by 1884.[9] In addition, the elephant trunks appear to tilt outward at a more pronounced angle than their current state, although this could be due to distortion in the photograph (fig. 5). Upon Rothschild’s death, Almina Herbert, Countess of Carnarvon, inherited the vases and ultimately sold them at auction in 1925.[10] They are depicted in the 1925 auction catalogue showing repairs to the trunks that also do not seem to match their current state; breaks can be seen close to the handles, and it appears that one of the trunks’ tips (48.1796) had broken and been reattached (fig. 5). The dealer Arnold Seligmann purchased the vases and, in 1926, sold them to Henry Walters, who bequeathed them to his wife, Sarah Walters (nee Jones), in 1931.[11] Upon her death, they were included in the 1941 auction of her collection and illustrated in the accompanying catalogue. The trunks seen in these photographs are consistent with their current appearance, indicating that the current trunks were added sometime between 1925 and 1941, possibly while in the possession of Seligmann before he sold them to Walters in 1926 (fig. 5).[12]

Other questions about the Walters vases have centered around visual evidence of repairs in conjunction with the unusually complicated color scheme and uncommon design elements. Although findings confirm that there are significant repairs, much of the color scheme and decoration appears to be original or restored based on the underlying original design.

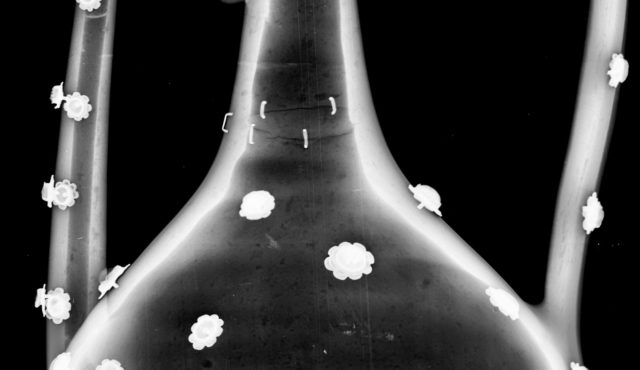

Existing elephant vases are typically decorated in a dominant ground color along with white glaze, gilding, and floral paintings, in addition to any central painted images.[13] The Walters’ vases employ a dominant pink ground color in conjunction with the typical white with gilding and pink floral patterns. An unusual variety of colors and decoration were added including red accents on the pink ground, a green rim and base, light and medium blue on the bejeweled elephant and beads, and a dark blue and gold dot pattern below the elephant’s neck. In addition, the base of the vase is painted with a pink and purple feather pattern with an overlaid red and green floral design. The pedestal scheme includes a bright blue, while the top surface depicts a different pink than the vase (fig. 6). Despite the inconsistent color scheme of this pair of vases, decorative elements link the body and pedestal together; the dark blue and gold dot pattern below the elephant necks matches that seen on the pedestals, along the edges of the bright blue panels.

Detail of pedestal (conservation documentation)

Slightly discolored overpaint, the overpainted Sèvres mark on the underside of the pedestal, and a brown adhesive between the vase and pedestal of one of the vases (48.1796) have made it apparent for some time that restoration had occurred although the extent was unknown. These restorations coupled with the color inconsistencies between the vase and pedestal have led some to question whether the pedestals are original and if details such as the unusual feather pattern are additions to cover related damage.[14] An understanding of the extent of damages and restorations using ultraviolet radiation and X-ray radiography sheds light on these questions.

Beyond the trunk alterations, one of the pair (48.1796) has extensive damage overall which is confirmed by examination with ultraviolet radiation and X-ray radiography (figs. 7 and 8).[15] However, both vases have breaks in the feather designs at the bases. X-ray radiography revealed a large network of breaks and cracks running through the body on the front, back, and proper right side including one of the handles. Ultraviolet induced visible fluorescence confirmed that extensive overpaint covers these breaks and large areas beyond.

The feathers and overlaid red flowers with green vines are unusual details for Sèvres and this time period, and are confirmed to be heavily overpainted to cover existing breaks on the most damaged vase (fig. 9). The tips of what looked to be feathers are visible above the edges of extensive overpaint, so a small area of overpaint was mechanically cleaned to further reveal the underlying design. The overpaint appeared to follow the underlying colors and pattern seen in the cleaned area, suggesting that the overpainted pattern likely approximates the original decorative scheme, in spite of the unusual design.[16] Immediately below these feathers, the green rings were also partially overpainted. XRF analyses revealed the green overpaint contains chromium, dating these, and possibly the adjacent repairs, to the early nineteenth century or later because chromium was not available to be used as a pigment until that time.[17] The remaining overpaint on the vases is largely confined to white backgrounds and the traditional floral wreaths, showing no evidence that the rest of the unusual color scheme has been altered.

Like the changes to the trunks, alterations to the feathers and bases can also be traced using the historic photographs (fig. 10). The 1884 Rothschild catalogue possibly shows indications of repair, with darker areas in the center of the feathers, but the photo is blurry and difficult to interpret. However, by the time of the 1925 auction, breaks were clearly visible in the feathers, green ring, and the base without any obvious overpaint. It is possible that these vases were broken prior to the 1884 photograph and are not clearly visible. As with the trunks, the current state of the vases can be seen in the 1941 photograph suggesting that they were also restored again after 1925. Two historic records note that one vase was damaged (presumably 48.1796): the 1918 posthumous inventory of Alfred de Rothschild’s collection includes a note reading “one badly broken” and the 1941 auction indicates “one repaired.”[18]

Much as the color scheme and design raised questions about the vase, the originality of the pedestals has been questioned for the same reasons coupled with a visible line of dark adhesive where these elements join on the more extensively damaged vase. This join, obscured in the X-radiograph, was possibly the result of a clean separation where both pieces would have been joined prior to firing. It is plausible that this piece could separate at this weaker join with an impact. The pedestal also has damage indicated in the X-radiograph, showing what is either a tight join or a crack unlike the full breaks seen in other areas. This damage to the pedestals also suggests that it was attached and likely broke when the rest of the vase was broken.

X-ray radiography complicated the initial interpretation of the base and pedestal repairs. A radiopaque material with bubbles was discovered on the interior of both vases (figs. 8 and 9). This material is dense, possibly indicating the presence of a lead-containing material. It was first thought to be a repair material that bubbled as it dried; however, a similar bubbling where glaze had pooled on a string of beads was found on the X-radiograph of the other vase (48.1797), indicating that this feature is likely the result of pooled glaze during the original manufacture. This material reaches higher up the walls of the interior of the less heavily damaged vase (48.1797) and is more puzzling and difficult to explain.

Returning to the question of the lack of consistency between the colors of the vases and pedestals, this is partially refuted by the continuation of the blue and gold dot pattern between the vase and pedestal. The overpaint on the pedestals is limited to break areas, indicating that the visible paint is original to that base. In addition, the bright blue pedestal panels that look like the well-known bleu céleste glaze used by Sèvres were analyzed using XRF. The elemental constituents are similar to a comparable blue glaze used on a Sèvres teacup (48.666a) in the Walters collection, showing that it is consistent with glazes used in the eighteenth century. While there is some limited restoration, there is no substantial evidence that the pedestals are later replacements, especially considering that the base of the less restored vase is intact.

In conclusion, historic documentation and technical analysis allow for a better understanding of the Walters’ Vases à tête d’éléphant. These vases have indeed been damaged and repaired overtime, as has been suspected by scholars. Although the major damage probably occurred before their publication in 1884, and definitely by 1925, restorations continued into the twentieth century. Despite these changes and the presence of extensive overpaint, the vases largely stay true to their original appearance with the exception of the missing candleholders and altered trunks. Although some of these restorations have slightly discolored over time, few of these repairs are obviously visible in the gallery, and the high level of work involved in the restoration has been the source of much confusion among scholars over the years. While the trunk alterations are different from the vases’ eighteenth-century design, the unusual color scheme and feather decoration do appear to date to their creation. There is also no overwhelming evidence that the current pedestals are not original to their manufacture. This technical analysis and historic documentation confirm that the Walters’ Vases à tête d’éléphant are unique within the existing examples of this rare porcelain form.

[1] Jeffrey Munger, European Porcelain in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018), 190.

[2] Examples can be seen in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Wallace Collection, Waddesdon Manor, and the Art Institute of Chicago. Jeffrey Munger has indicated that nineteen are currently in public institutions. Munger, European Porcelain, 192; and Munger, “Elephant-head vase (vase à tête d’éléphant),” Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 2015,

[3] The Sèvres records, Registres de ventes, report that Madame de Pompadour ordered two rose and green elephant-head vases with chinoiserie scenes. Tamara Préaud cites from Sèvres records (M. N. S. Archives, Registre Vy 3, folio 115) that “2 vazes elephants rozes et verdes chinois” were delivered to Madame de Pompadour on February 7, 1762, for 360 livres each. “Sèvres, la Chine et les ‘chinoiseries’ au XVIIIe siècle,” The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 47 (1989): 41.

[4] Dodin worked from the draftsman Gabriel Huquier’s (1695–1772) pastiches of François Boucher’s (1703–1770) chinoiseries. See Carl Christian Dauterman, “Chinoiserie Motifs and Sèvres: Some Fresh Evidence,” Apollo 84 (December 1986): 478–79; and Perrin Stein, “Boucher’s Chinoiseries: Some New Sources,” The Burlington Magazine 138, no. 1122 (September 1996): 598–604.

[5] Only the boat-shaped potpourri vase, also represented in the Walters collection (48.559), would have been more complex. Duplessis designed the elephant-head vases two years prior to the potpourri vase.

[6] The elephant-head vases are listed in both the wheel-thrown and mold-made sections of the Sèvres ledgers. As a result, it has been suggested that the body of the vases were wheel-thrown, while the elephant heads and pedestals were mold-made. Savill, Wallace Collection Catalogue, 1:154. X-ray radiography of the Walters’ vases shows that the bodies were constructed of two sections that were stacked and joined at the widest point and smoothed. There are no obvious indications that the bodies were wheel-thrown, which could be due to the finishing process (fig. 8).

[7] The Walters vases are classified as “Shape B,” the second form manufactured, which included the addition of handles, strings of applied beads at the neck and shoulder, and jewels for the elephants’ heads. Shape B was produced in three sizes, with the Walters vases classified as the third, and smallest, size. Rosalind Savill, The Wallace Collection Catalogue of Sèvres Porcelain (London: Trustees of the Wallace Collection, 1988), 1:154.

[8] An example at the Metropolitan Museum of Art illustrates one of the shapes possible for the now missing porcelain candleholders (acc. no. 1976.155.61). Carl Christian Dauterman wrote about the Walters’ elephant vases in 1966 noting that “each trunk is pierced to receive a porcelain candle socket, long since lost.” It is presumed that he made this assumption based on other examples because the current porcelain replacement trunks would have then been present. Dauterman, “Chinoiserie Motifs and Sèvres,” 478.

[9] Charles Davis and J. (John) Thompson, A Description of the Works of Art Forming the Collection of Alfred de Rothschild (London, 1884), 2:89.

[10] Catalogue of Fine French Furniture, Sèvres Porcelain And Objects of Art And Vertu, the Property of the Right Hon. Almina, Countess of Carnarvon to Whom They Were Bequeathed by the Late Alfred De Rothschild, Esq., Which Will Be Sold by Auction by Messrs Christie, Manson et Woods (London, 1925).

[11] William R. Johnston, William and Henry Walters, The Reticent Collectors (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1999), 289.

[12] See Sarah Walters and Parke-Bernet Galleries, The Mrs. Henry Walters Art Collection […] (New York: Sotheby’s, 1941), 142–43. The Walters Art Museum acquired the vases at the auction in 1941.

[13] The author has seen one other example beside the Walters’ vases that includes another color beyond the dominant ground color and white. An example (acc. no. 3013) at the Waddesdon Manor collection combines both pink and green on the vase and pedestal but with no additional colors.

[14] Clare Le Corbeillier, Curator, European Sculpture of Decorative Arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art raised this question in a letter to William Johnston. Clare Le Corbeillier to William Johnston, March 4, 1994, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, curatorial files, acc. no. 48.1796-7.

[15] Computed x-ray radiography was performed with a Varian X-ray tube with a Polaris MC-250 control system, GE CR50P plate scanner, and Rhythm software. X-ray radiographs were edited in Adobe Photoshop and with Lucius Pro.

[16] It is worth noting that the original feather tips on both vases have slightly different appearances as if they were completed by two different painters. The feathers on 48.1796 have heart-shaped tops, while those on 48.1797 peak in the center.

[17] Artax XRF spectrometer operated at 50 kV, 700 microAmps for 180 seconds with 1.5 mm collimation and helium purge.

[18] “The Estate of Alfred C de Rothschild Esq. deceased. 1 Seamore Place, W.” Messrs. Christie’s Inventory of the Contents of 1 Seamore Place, 1918.