Léonard Limosin (ca. 1505–1575/77), Portrait of Marguerite of Navarre, ca. 1540–45?, painted enamel on copper, silver frame. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Bequest of Henry Walters, 1931, acc. no. 44.504

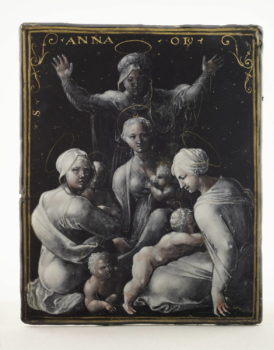

The identity of the female sitter depicted in a Limoges painted enamel portrait at the Walters Art Museum has long perplexed scholars. Shown in bust-length against a black background, the woman wears the deuil blanc, or “white mourning” attire of sixteenth-century France, and gazes at a simple dark cross (fig. 1). The portrait’s reverse side depicts Saint Anne with the Virgin and Saint Elizabeth—a figural grouping known traditionally as the Holy Kinship—painted in gold camaïeu (meaning cameo or monochromatic) and derived from Marcantonio Raimondi’s (1480–1534) engraving The Virgin and the Cradle (ca. 1520) (fig. 2).[1]

In previous studies of this enamel portrait, the sitter has often been loosely associated with one of three French noblewomen: Anne of Brittany (1477–1514), wife of King Louis XII; Louise of Savoy (1476–1531), mother of King Francis I of France; and Louise’s daughter—Marguerite d’Angoulême (1492–1549), Queen of Navarre and noted author of Renaissance literary works such as the Heptaméron (published posthumously in 1558).[2] The following seeks to securely identify the woman portrayed in the Walters enamel as Marguerite, considering the ways in which previously unexplored verbal and visual sources for the enamel portrait confirm such an identification.[3] In particular, this analysis suggests a new date of execution for the portrait (late 1540s), and elucidates the personal significance of the deuil blanc and the Holy Kinship to Marguerite at this time; it also poses broader questions concerning the ways in which Raimondi’s engraving of Saint Anne was tailored to commemorate the political power and dynastic lineage of elite families long after the engraving’s initial printing and circulation.[4]

Marcantonio Raimondi (1480–1534), The Virgin and the Cradle with Saint Elisabeth and Saint Anne, 1520, engraving. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of the Print Club of Cleveland, acc. no. 1921.174

With their vibrant colors, painted enamels produced in the city of Limoges emerged as a popular medium for decorative plaques, caskets, and dishes, as well as intimate portraits of French monarchs and courtiers by the third decade of the sixteenth century.[5] The French artist Léonard Limosin (ca. 1505–1575/77), to whom this portrait of Marguerite is attributed, executed many of these enamel portraits after arriving at the court of Fontainebleau around 1536.[6] First appointed by Francis I to serve as the monarch’s valet de chambre, Limosin was later appointed émailleur et peintre ordinaire de la chambre by King Henry II (1519–1559) in 1548.[7] Although no known record for an enamel portrait of Marguerite survives today, her prominent status as the sister of Francis I and later Queen of Navarre warranted the rendering of her likeness in manuscript illuminations, panel paintings, drawings, and medallions. [8] It is thus hardly surprising that Limosin, the preeminent enamel portraitist at the French court, would portray Marguerite’s image in the form of a painted enamel.

Jean Clouet (1480–1541), Marguerite d’Orléans, Queen of Navarre, 1525, black and red chalk on paper. Musée Condé, MN 43. Photo: Michael Urtado and © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Limosin likely derived Marguerite’s likeness from a drawing attributed to the court artist Jean Clouet (1480–1541) that significantly predates the Walters enamel.[9] Clouet’s drawing was completed around 1525 after the death of Marguerite’s first husband, Charles IV, Duke of Alençon (1489–1525), and depicts the sitter wearing a white veil and pleated wimple, nearly identical to those represented in the enamel portrait (fig. 3). The deuil blanc resembled the habits of contemporary female monastic orders (see, for example, Sofonisba Anguissola’s portrait of a Dominican nun [ca. 1532–1625]) and appeared frequently in the period’s painted portraits of widows, such as Bernard van Orley’s (1487–1541) Portrait of Margaret of Austria (after 1518, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels) and Francois Clouet’s (1510–1572) Portrait of Mary Queen of Scots (ca. 1560–61).[10] In addition to her attire, the sitter’s facial features in the Walters enamel are quite similar to those visible in a panel portrait (ca. 1527) attributed to Clouet and thought to depict Marguerite (fig. 4), as well as a posthumous illuminated portrait of Marguerite from Queen Catherine de’ Medici’s (1519–1589) Book of Hours (1572–75).[11] Limosin also shows Marguerite contemplating a dark crucifix, a device that is surely intended as a conventional iconographic reference to her patron saint, Margaret of Antioch (289–304).[12]

Jean Clouet (1480–1541), Portrait of Marguerite, ca. 1527, oil on oak panel. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, Presented to the Walker Art Gallery by the Liverpool Royal Institution in 1948, acc. no. WAG 1308

As previously stated, Limosin derived the image of the Holy Kinship on the portrait’s reverse from a design by Marcantonio Raimondi.[13] Limosin’s configuration differs slightly from Raimondi’s original engraving, The Virgin and the Cradle, as the enamel depicts Saint Anne and the Virgin adorned with double-ringed haloes, and underlines the infant Christ’s divinity through the addition of two fleur-de-lis—the symbol of the French monarchy—behind his head.[14] Additionally, the phrase “ave mater matris Dei” (hail mother of the mother of God) is inscribed around the enamel’s top border. The presence of this inscription reveals that Limosin’s design adheres to a standardized pictorial convention for the Holy Kinship, as this exact phrase accompanies several other sixteenth-century representations of Saint Anne with her descendants, such as Domenico Beccafumi’s (1486–1551) fresco of Saint Anne with the Virgin and Child between Mary Magdalene and Saint Ursula, as well as Francesco da Sangallo’s (1494–1576) sculpture The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (1526).[15]

Although initially printed around 1520, The Virgin and the Cradle inspired depictions of Saint Anne and the Holy Kinship long after its initial execution—as demonstrated in Giovanni Maria Butteri’s (1540–1606) Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Members of the Medici Family (1575) (fig. 5) and Rembrandt van Rijn’s (1606–1669) Presentation at the Temple (1627–28).[16] In particular, Butteri’s painting reflects how Raimondi’s design could serve as a readily adaptable allegorical expression of familial power and dynastic memory. The image portrays both living and deceased members of the family of Grand Duke Francesco I de’ Medici (1541–1587). Duke Francesco is shown as Saint George, his brother Ferdinando I (1549–1609) is represented as Saint Damian, and his sister Isabella de’ Medici (1542–1576) is visible as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, while his father, Grand Duke Cosimo I (d. 1574), is painted as Saint Cosmas, and his mother, Eleonora of Toledo (died 1562), is pictured as the Virgin.[17] Completed one year after Cosimo de’ Medici’s death, Butteri’s image reinforces the survival of the ducal line and Francesco’s legitimate assumption to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. Considered more broadly, the representation of past and present members of the Medici family under the outstretched arms of Saint Anne conveys not only the divine appointment of the Medici family as the heads of the Florentine principate, but also the significant role that images of familial lineage played in securing political power during transitional periods.[18]

Giovanni Maria Butteri (1540–1606), Virgin and Child with St. Anne and Members of the Medici Family as Saints, 1575, oil on panel. Cenacolo di Andrea del Sarto, Florence

The Holy Kinship on the reverse of the Walters enamel portrait performs a similar function as Butteri’s Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Members of the Medici Family, although Limosin’s design serves a more allusive purpose. Like Raimondi’s The Virgin and the Cradle, Marguerite’s portrait depicts the Holy Kinship as an intimate familial grouping, focusing on Saint Anne, the Virgin, and the infant Christ. This Trinitarian form of the Holy Kinship corresponded directly to contemporary Reformist debates that disputed the Church’s traditional teachings on the life of Saint Anne. By the sixteenth century, Saint Anne had become one of the most venerated saints in western Europe, with the details of her life circulating in a text known as the Protoevangelium of James, probably written during the second century CE.[19] The Protoevangelium proclaimed that Saint Anne had been married three times, and with each husband gave birth to a child named Mary. In turn, these three Marys gave birth to as many as twenty-three descendants of Saint Anne.[20] While official Church doctrine promoted the three marriages of Saint Anne, the writings of Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples (1455–1536), a prominent French theologian and humanist active during the first quarter of the sixteenth century, reduced the Holy Kinship to three persons: Saint Anne, the Virgin, and Christ, establishing the Virgin as Saint Anne’s only daughter. In the second edition of his De Maria Magdalena (1518) Lefèvre denounced the Protoevangelium’s version of the life of Saint Anne, arguing that her three marriages would undermine her chastity and the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin.[21] As Myra Orth and others have previously recognized, Louise, Francis, and Marguerite became directly associated with the new, reformed version of the Holy Kinship in the Petit livret faict a l’honneur de madame saincte Anne (ca. 1525), written by Lefèvre and Louise’s Franciscan advisor Francis du Moulin.[22] While Lefèvre was persecuted by the Church for attempting to revise canonical teachings, he was ultimately protected by Marguerite at her court at Nérac until his death.[23]

Leonardo da Vinci (1452‒1519), The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, ca. 1503, oil on panel. Musée du Louvre, INV 776. © RMN ( Musée du Louvre)/Rene Gabriel Ojeda

Illumination from a prayer book, “Heures de Marguerite de Valois, soeur de François I er.”, 1501–1600, 1527. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, NAL 83

Within the context of these theological debates, engravings and painted images of the Holy Kinship displayed and circulating at the court of Fontainebleau emerged as powerful expressions of the French monarchy’s three most important figures. In contrast to the fifteenth-century northern European tradition, in which artists portrayed Saint Anne alongside many descendants, Italian imagery exhibited at the French court during the first half of the sixteenth century—such as Raimondi’s engraving and Leonardo da Vinci’s (1452‒1519) The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (ca. 1510) (fig. 6)—rendered the Holy Kinship as a compact, Trinitarian grouping, often depicting a heightened sense of intimacy between Saint Anne, the Virgin, and the infant Christ.[24] Although these intimate scenes of the Holy Kinship originated in Italy, meaning their conception and execution were not directly informed by French Reformist debates surrounding the marriages of Saint Anne, such images resonated with prayer books, treatises, and other elaborately illustrated texts that designated Marguerite, Francis, and Louise as a “noble Trinity.” [25] For example, an illumination from a prayer book (1527) produced for Marguerite illustrates two seraphim holding a banner with the phrase “O Nobile Ternarium Regis /Matris/ et Sororis unum est desiderium” over the arms of France, while Christ reigns above, surrounded by angels (fig. 7).[26] As Marguerite and her two closest family members became directly affiliated with a more intimate version of the Holy Kinship, Limosin certainly adapted Raimondi’s The Virgin and the Cradle to the Walters enamel portrait in order to evoke the “noble trinity” of France, of which Marguerite was a member.

Nardon Pénicaud (1470–1542/43), Triptych with Crucifixion, ca. 1495–1525, painted and gilded enamel on copper. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Bequest of Henry Walters, 1931, acc. no. 44.149

Jean Pénicaud I (ca. 1490–after 1543), The Agony in the Garden, ca. 1520–25, painted enamel on copper, partly gilded. The Frick Collection, Henry Clay Frick Bequest, 1916.4.06. © The Frick Collection

However, even when the personal significance of the Holy Kinship to Marguerite is clarified, the choice of mourning attire for this enamel portrait remains puzzling. If Limosin depicts Marguerite as a grieving widow, the execution of the enamel portrait would date prior to her remarriage to Henry II of Navarre (1503–1555) in 1527, at a time when Limosin may have worked in the Pénicaud family workshop in Limoges.[27] Yet the subtle rendering of the shadows throughout Marguerite’s face and veil is stylistically inconsistent with enamels that can be securely dated to the 1520s, such as Nardon Pénicaud’s (1470–1542/43)Triptych with the Crucifixion (fig. 8), or Jean I Pénicaud’s (ca. 1490–after 1543) The Agony in the Garden (fig. 9).[28] The fine quality of painting and attention to detail in Marguerite’s portrait are overall characteristic of Limosin’s signed portraits of royals and courtiers from the middle of the sixteenth century, such as Henry II of France.[29] Moreover, designs derived from Raimondi’s The Virgin and the Cradle appear exclusively on enamels executed during the second and third quarters of the sixteenth century, such as enamel plaques like Martial Ydeux’s The Virgin and Child Between Two Saints, from the mid-sixteenth century, and Jean Pénicaud II’s (1515–1588) The Lineage of Saint Anne, produced in the second half of the sixteenth century (fig. 10).[30] That this example of Holy Kinship imagery does not surface on painted enamels until the later-second and third quarters of the sixteenth century further suggests that Limosin executed Marguerite’s portrait around the middle of the century.[31]

Fig. 10

Martial Ydeux, Plaque: The Virgin and Child between two saints, 1540–60, painted enamel on copper. Louvre, OA 969 B. © 2006 RMN-Grand Palais (Louvre museum) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

Jean Pénicaud II (1515–1588), Plaque: The Lineage of Saint Anne, 1550–1600, painted enamel on copper. Louvre, OA 4003. © 2018 RMN-Grand Palais (Louvre museum) / Stéphane Maréchalle.

It is possible that Marguerite wears the deuil blanc in order to signify the death of a family member, most likely Francis I, with whom she was particularly close. In a letter (1544) written during the final years of Francis’s life, Marguerite described how much she cherished their relationship: “it pleases you to do for me as much in the office of king, of master, of father and brother and of true friend, that I cannot regard you in any of these aspects without finding myself astonished by the love it pleases you to show me.”[32] Following Francis’s demise in 1547, Marguerite composed a series of moving Chansons Spirituelles (Spiritual songs) that explicitly conveyed her sorrowful state, along with two other works: the Comedie sur le trepas du roy (Comedy on the death of the king) and the poem Le Navire (The ship).[33] Such mournful prose may provide a rationale for why an enamel portrait of Marguerite in mourning was commissioned in the later 1540s. Although several of Marguerite’s relatives died before Francis, none of their deaths inspired such sorrowful writings.[34] The presence of the Holy Kinship on the reverse of Marguerite’s portrait supports such reasoning. This particular grouping of figures certainly alludes to the relationship between Marguerite, and her predeceased brother and mother, and—as Butteri’s later painting of the Medici family shows—imagery of the Holy Family with Saint Anne could reference predeceased family members not only as a way to commemorate the dead, but to recognize the legitimacy and consolidation of one’s political power through lineage. After Francis’s death, Marguerite’s prominent status at court diminished, and her political influence waned as her relationship with the new King of France, her nephew Henri II (1519–1559), became strained.[35] If the Walters enamel portrait was commissioned on the occasion of Francis’s death, the presence of the Holy Kinship on its reverse not only commemorates the intimate relationship Marguerite shared with her brother, but may also highlight her historically close ties to the French crown as a way to legitimize her continued contact with the French court after Francis’s demise. Moreover, the reference to Saint Margaret through the crucifix included in Marguerite’s portrait may also serve a dual purpose, alluding to the sitter’s name, and—just as Margaret made the sign of the cross in order to overcome her suffering—her reliance upon the Christian faith during her time of mourning.[36]

© Sotheby’s London.

That the Walters enamel portrait may have been executed after Francis’s death could help to elucidate why three similar examples of this portrait exist, each of which portrays an identical sitter wearing the deuil blanc with a different religious composition on the reverse. The back of one version (auctioned at the Cyril Humphris sale at Sotheby’s New York in 1995) depicts Saint Margaret standing on a dragon, holding a cross in her uplifted hands and a laurel wreath woven through her hair.[37] Painted on the reverse of a second portrait (formerly in the Kofler-Truniger collection in Lucerne) is an image of Saint Margaret kneeling under a colonnade adoring the Virgin and Child, who are held by winged angels.[38] Just as the crucifix held by Marguerite in the Walters enamel references her saintly namesake, the presence of imagery relating to Saint Margaret on these two enamels suggests that the sitter’s name is Margaret.[39] On the reverse of a third example auctioned by Sotheby’s in 2016, two female figures wear identical white veils and kneel before an enthroned Virgin and Child (fig. 11). A Latin prayer to the Virgin is inscribed on the white border.[40]

Léonard Limosin (ca. 1505–1575/77), Medallion, ca. 1530–40, painted enamels and gilding on copper in gilt metal frame. Victoria & Albert Museum, acc. no. 7912-1862. © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

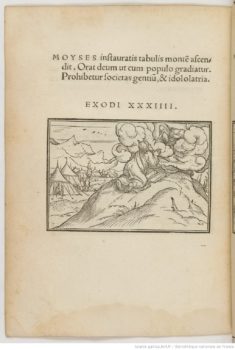

Besides these three additional portraits, a painted enamel portrait at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), also attributed to Limosin, exhibits comparable imagery and stylistic qualities to the Walters portrait of Marguerite (fig. 12).[41] On the reverse of this unidentified portrait, there is an image of Moses receiving the Ten Commandments, similarly painted in gold camaieu. The image of this Old Testament narrative is likely derived from a woodcut (1525–30) in Hans Holbein the Younger’s (1497–1543) Icones (ca. 1525–26), as well as a woodcut by Bernard Salomon (1506–1566), published in 1553 (fig. 13).[42] In 2015, Thierry Crépin-Leblond proposed that the Walters, Humphris, Kofler-Truniger, and V&A enamel portraits may have been commissioned in 1536 to commemorate the Treaty of Cambrai (1529), which temporarily ended the wars between Francis I and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500–1558), and was negotiated by Marguerite, Louise, Margaret of Austria (1480–1530), and Marie of Luxembourg (1472–1547).[43] Crépin-Leblond argues that the Walters, Humphris, Kofler-Truniger, and V&A enamels may depict Louise, Marguerite, Marie, and Margaret of Austria.[44] However, his analysis does not account for the Sotheby’s enamel auctioned in 2016, which necessitates the reevaluation of these portraits on stylistic and iconographical grounds.

Fig. 13

Léonard Limosin (ca. 1505–1575/77), Medallion, ca. 1530–40, painted enamels and gilding on copper in gilt metal frame. Victoria & Albert Museum, acc. no. 7912-1862. © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Bernard Salomon (1506–1566), woodcut from Claude Paradin, Quadrins historiques de la Bible (1555). National Library of France

As the 2016 Sotheby’s catalogue notes, the Walters, Humphris, and Kofler-Truniger portraits exhibit nearly identical female likenesses to the Sotheby’s enamel, suggesting that they each depict the same sitter.[45] That these four enamel portraits each depict Marguerite, and were commissioned sometime between Francis I’s death, in 1547, and Marguerite’s death in 1549, is certainly plausible. All appear to be derived from Clouet’s original drawing, and—as previously stated—the subtle rendering of the light and shadows on each sitter’s face is stylistically consistent with mid-sixteenth-century Limosin enamel portraits. The death of a monarch would certainly have warranted such an expensive commission, as suggested by the high quality of painting and attention to detail throughout these portraits.[46] Although it remains impossible to determine exactly who commissioned this series of enamel portraits, if they were executed upon Francis’s death, they were likely intended for Marguerite’s family members or close confidants, as their subject matter is deeply personal.

Ultimately, the Walters enamel portrait reveals that while Renaissance painted enamels did derive their imagery from widespread, conventional sources, they could also use powerful, allusive imagery to tell a uniquely personal story. In this case, Marguerite’s portrait not only evokes the sorrowful and spiritual themes present throughout her writings from this period, but also employs a widely disseminated version of the Holy Kinship to commemorate her predeceased family members, and reinforce her political and social standing during a transitional period in her life and the hierarchy of the French court. Like Butteri’s Portrait of the Medici Family with Saint Anne, Marguerite’s Holy Kinship asks for viewers to consider the sitter’s relationship to both the living and the dead, foregrounding familial memory on the path to maintaining political authority.

A special thank you to Joaneath Spicer for her input on Holy Kinship imagery, and the editors of this essay for their valuable feedback on this subject.

[1] For an overview of Holy Kinship imagery, see Interpreting Cultural Symbols: Saint Anne in Late Medieval Society, ed. Kathleen M. Ashley and Pamela Sheingorn (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1990). Gold camaïeu involves building up one color of enamel to create highlights and light areas against a dark background, see Philippe Verdier, Catalogue of the Painted Enamels of the Renaissance (Baltimore: The Walters Art Gallery, 1967), xi. Although most sources attribute the Virgin and the Cradle design to Raimondi, it was also printed by Marco Dente (1493‒1527). See Giorgio Marini, “La Madonna del Catino,” in Raffaello Il Sole Delle Arti, ed. Gabriele Barucca and Sylvia Ferino-Pagden (Milan: Silvana, 2015), No. 40, 236; Max Weaver, “The Virgin and the Cradle,” in Marcantonio Raimondi, Raphael, and the image multiplied, ed. Edward H. Wouk and David Morris (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016), No. 77, 213.

[2] On the attribution to Anne of Brittany, see Philippe Verdier, Catalogue, 103‒4. Myra Orth argued that the portrait represents Louise because the Duchess remained a widow after the death of her husband, Charles of Orléans (died 1496) and became directly affiliated with Saint Anne in the treatise Petit livret, faict al’honneur de madame saincte Anne, published during the first quarter of the sixteenth century. See Orth, “A Portrait Enamel of the French Renaissance,” Walters Art Gallery Bulletin 31 (1979), 2‒3; Orth, “Madame Sainte Anne: The Holy Kinship, the Royal Trinity, and Louise of Savoy,” in Interpreting Cultural Symbols: Saint Anne in Late Medieval Society, ed. Kathleen M. Ashley and Pamela Sheingorn (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1990), 199‒218. For studies that have associated the sitter with Marguerite and other prominent French noblewomen, but never conclusively identified her, see Thierry Crépin-Leblond, Une Reine sans Couronne?: Louise de Savoie, mere de Francois Ier (Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 2015), 124; “Roundel with a Portrait of a Noblewoman. Probably Louise of Savoy, or Marguerite of Angoulème, Queen of Navarre. And with the Adoration of the Virgin and Child on the Reverse.” Sotheby’s, 2016, http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2016/treasures-l16303/lot.3.html.

[3] Walters’ curator Joaneath Spicer, the James A. Murnaghan Curator of Renaissance and Baroque Art at the Walters, has long proposed that the enamel likely represents Marguerite, although the diverse range of visual and verbal sources that support this identification have never been explored.

[4] Previous studies have dated this portrait to the 1520s and 1530s. See Orth, “A Portrait Enamel,” 2‒3; Orth, “Madame Sainte Anne,” 199‒218; Crépin-Leblond, Une Reine sans Couronne?, 124; Verdier, Catalogue, 103‒4.

[5] Limoges enamelers depicted both religious and mythological subjects in their designs. See for example Nardon Pénicaud’s (1470‒1542/3) early Triptych with the Crucifixion (ca. 1495–1525); Pierre Reymond’s (ca. 1513‒1584) Casket with the Labors of Hercules (ca. 1540); Léonard Limosin’s Dish with the Wedding Banquet of Cupid and Psyche (ca. 1560); Pierre Courteys’s (ca. 1520–1586) Ewer with Triumph of Venus and Neptune (ca. 1567).

[6] Sophia Baratte, Léonard Limosin au musée du Louvre (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1993), 46‒57; Philippe Verdier and Myra Orth previously attributed the portrait to Jean II Pénicaud (ca. 1515–1588). See Verdier, Catalogue, 103‒4, cat. 50 and Orth, “A Portrait Enamel,” 2‒3.

[7] Baratte, Léonard Limosin, 16.

[8] For a discussion on painted and drawn portraits of Marguerite attributed to Jean Clouet, see Cécile Scailliérez, François Ier par Clouet: Exposition-dossier du département des Peintures (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1996), 84‒96. For a portrait medal (1512), see Muriel Barbier, Une Reine Sans Couronne?, 57.

[9] Limosin often adapted his portraits from Clouet’s drawings. See Henri Zerner, The School of Fontainebleau: Etchings and Engravings (New York: Henry N. Abrams, 1973), 32. The drawing by Clouet is located in the Musée Conde (MN 43). On the attribution of this drawing to Clouet, see Scailliérez, Francois Ier, fig. 57, 88. It is worthwhile to mention that visible in the upper right-hand corner of Clouet’s drawing is the annotation “La feu Reyne de Navarre, marguerite,” which explicitly identifies the sitter. This annotation was likely added to Clouet’s work during the second half of the sixteenth century when Queen Catherine de’ Medici (1519‒1589) collected many of Clouet’s drawings. For more on the annotation, see Étienne Moureau-Nélaton, Les Clouet et Leurs Émules, vol. II (Paris: Henri Laurens, 1924), 15; Mellen, Jean Clouet: Drawings, Miniatures and Paintings (London: Phaidon, 1971), 230, cat. no. 124. On Catherine de’ Medici’s collection, see Ian Wardropper, “The Flowering of the French Renaissance.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 62 No.1 (2004): 8.

[10] On the relationship between the deuil blanc and monastic apparel, see Paul Matthews, “Apparel, Status, Fashion: Woman’s Clothing and Jewellery,” in Women of Distinction: Margaret of York, Margaret of Austria, ed. Dagmar Eichberger (Leuven: Brepols, 2005), 151. Sofonisba’s The Artist’s Sister in the Garb of a Nun is located in the Southampton City Art Gallery (SCAG 3). For Bernard van Orley’s Margaret of Austria, see Eichberger, cat. 19, 84. The painting is in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels (inv. no. 4059). The Portrait of Mary Queen of Scots is located in the Palace of Holyrood House (RCIN 403429).

[11] For more on the panel portrait attributed to Clouet, see Scailliérez, François Ier par Clouet, 84‒96. For Catherine de’ Medici’s Book of Hours, see Heures de la reine Catherine de Medicis, BNF NAL 82.

[12] According to an episode from Jacobus da Varagine’s (1228–1298) The Golden Legend (ca. 1260), after being swallowed by a dragon, Saint Margaret made the sign of the cross, splitting open the belly of the beast. Jacobus da Varagine, The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints, vol. I,trans. William Granger Ryan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 369. For an overview on the traditional iconography of Saint Margaret, see Josepha Weitzmann-Fiedler, “Zur Illustration der Margaretenlegende,” Müncher Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst 17 (1966): 17‒48. Depictions of Saint Margaret existed in various media at the sixteenth-century French court, appearing in manuscripts, like Jean Bourdichon’s (1457–1521) illumination in the Grandes Heures d’Anne de Bretagne (ca. 1505–10, BNF Latin 9474, fol. 205v), and paintings, like Giulio Romano’s (1499–1546) Saint Margaret of Antioch (ca. 1518). Romano’s painting of Saint Margaret was commissioned by Pope Leo X (1475‒1521), possibly for Marguerite herself, and is derived from a drawing by Raphael (1483‒1520), see http://cartelen.louvre.fr/cartelen/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=13972&langue=en.

[13] Raimondi derived his design from a sketch by Raphael (1483–1520) that was later executed in a series of early sixteenth-century paintings by Giulio Romano and Gianfrancesco Penni (1490–1528). See Wouk and Morris, 213. The engraving has been compared to Romano’s The Holy Family (ca. 1518), now in the Prado, which depicts the Virgin and Child with Saint Elizabeth and an infant Saint John the Baptist. See Raphael dans les collections françaises, no. 29, 349. It has also been linked to Romano’s Madonna with the Basin (around 1525), now in Dresden’s Gemädegalerie Alte Meister. See Barucca and Ferino-Pagden, 236.

[14] Anne-Marie Lecoq has observed that, since the fourteenth century, the fleur-de-lis was associated with the Holy Trinity, the three lilies symbolizing the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit: “Depuis le XIV siècle, les auteurs se plaisaient a souligner le symbolism trinitaire des armes de France, les trios lys d’or identiques sur l’azur celeste, deux en chef et un en pointe, symbolisant le Pere et le Fils, et le Saint-Esprit qui procede de l’un et de l’autre.” See Lecoq, François Ier imaginaire: Symbolique et politique à l’aube de la Renaissance française (Paris: Macula, 1987), 398.

[15] On Beccafumi’s fresco, see Alberto Cornice, “Restauri,” Prospettiva 5 (1976): 74–75. Regarding the sculpture by Francesco da Sangallo, Hebrew inscriptions on the necklines of the garments of Anne and Christ phonetically spell out the Latin Ave Mater, matris dei. See Colin Eisler, Abbey Kornfeld, and Alison Rebecca W. Strauber, “Words on an Image: Francesco da Sangallo’s Sant’Anna Metterza for Orsanmichele,” Studies in the History of Art 76 (2012): 296. This inscription may also be indicative of the portrait’s function. As Michael Alan Anderson has observed, Ave mater matris Dei is the title of a motet—a short, polyphonic choral arrangement—with lyrics adapted from an office antiphon for Saint Anne, printed in 1534 by the French publisher Pierre Attaingnant. See Anderson, St. Anne in Renaissance Music: Devotion and Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 189. That this inscription could evoke an ecclesiastical melody is not unique to Marguerite’s enamel portrait. For example, Stephen Bailey has noted that at the top of the central panel of the Walters’ late fifteenth-century Triptych of the Holy Kinship, there is the inscription “Ave regina coelorum / Mater regis angelorum” (Hail queen of the heavens / Mother of the king of angels), which was derived from a fifteenth-century motet by the English composer Walter Frye (active ca. 1450–75). For more on this triptych, see Stephen Bailey, “A ‘Holy Kinship’ Attributed to the Master of the Magdalen Legend,” The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 41 (1983): 7–16.

[16] A version of Raimondi’s The Virgin and the Cradle was also produced by Marco Dente da Ravenna (1493‒1527), see Giorgio Marini, Raffaello Il Sole Delle Arti, no. 40, 236. On Butteri’s painting see Karla Langedijk, Portraits of the Medici:15th‒18th Centuries, Volume I (Florence: Studio per edizioni scelte, 1981), 118‒19, 424. On the possible relationship between Raimondi’s engraving and Rembrandt’s painting, see Raphael dans les collections francaises, no. 29, 349.

[17] Langedijk, Portraits of the Medici, 118‒19

[18] For more on the political, propagandist role of portraiture during the reigns of Cosimo I and Francesco I de’ Medici, and the divine appointment of Cosimo I de’ Medici and his heirs as the Dukes of Tuscany, see Kurt W. Forster, “Metaphors of Rule: Political Ideology and History in the Portraits of Cosimo I de’ Medici,” Kunsthistorisches Institutes in Florenz, vol. 15, no. 1 (1971): 65‒104; Elizabeth Pilliod, “Cosimo I de’ Medici: Lineage, Family, and Dynastic Ambitions,” in The Medici: Portraits and Politics 1512‒1570, ed. Keith Christiansen, Carlo Falciani (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2021), 121‒60.

[19] The Protoevangelium circulated throughout medieval and Renaissance Europe in Latin reworkings. See Sheila M. Porrer, Jacques Lefèvre d’Etaples and the Three Maries Debates (Paris: Droz, 2009), 63‒64.

[20] Porrer, Jacques Lefèvre, 69‒71; Orth, “Madame Saint Anne,” 202. See also Pamela Sheingorn, “Appropriating the Holy Kinship: Gender and Family History,” in Interpreting Cultural Symbols: Saint Anne in Late Medieval Society, ed. Kathleen Ashley and Pamela Sheingorn (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1990), 169.

[21] Porrer, Jacques Lefèvre, 62‒63.

[22] Orth, “Madame Saint Anne,” 204‒14; Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples and François de Moulins de Rochefort, Petit livret faict a l’honneur de madame saincte Anne et de la royne, sa fille, vierge pure, mere de Jesus-Christ, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Ms-4009 réserve, fol. 8v. In the text, Du Moulin illustrates the Church’s traditional approach to the Holy Kinship, writing in the upper left-hand corner of the image and in the surrounding text: “This image is apocryphal and false although the Theologians of Paris have long approved of it. And speaking in reverence to you, MADAME, those who said so lied. For Saint Anne, good and chaste widow, was satisfied with one husband—that is Joachim who was father only of the Virgin Mary.” See Orth, “Madame Saint Anne,” 212; Francis du Moulin, Petit livret, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, MS-4009, fol. 8r, 9r.

[23] R. J. Knecht, Renaissance Warrior and Patron: The Reign of Francis I (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 114; Patricia F. Cholakian, Rouben C. Cholakian, Marguerite de Navarre: Mother of the Renaissance (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), 175.

[24] On fifteenth-century northern European paintings of the Holy Kinship, see Pamela Sheingorn, “Appropriating the Holy Kinship,” in Interpreting Cultural Symbols: Saint Anne in Late Medieval Society, ed. Kathleen M. Ashley and Pamela Sheingorn (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1990), 169–76. For an example of this earlier type of Holy Kinship imagery in the Walters collection, see Bailey, “A ‘Holy Kinship,’” 7‒16. Other Italian paintings executed for Francis I that centered on the relationship between Saint Anne, her daughter, and her grandson, included Andrea del Sarto’s (1486–1530) Holy Family with Angels (1515–16) and Raphael and Giulio Romano’s Holy Family of Francois I (1518). Leonardo completed his The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne around 1510, long before he took up residence at Francis’s court in 1517, although the painting was made visible to French courtiers who were familiar with contemporary Reformist debates that directly associated the royal family with the three members of the Holy Kinship. See Anderson, St. Anne, 218–220; Orth, “Madame Saint Anne,” 200.

[25] Lecoq, François Ier, 396–97; Leah Middlebrook, “’Tout mon office’: Body Politics and Family Dynamics in the verse epîtres of Marguerite de Navarre,” Renaissance Quarterly 54 (2001): 1119–20.

[26] “O noble trinity, of the King/Mother/and Sister, unity is your desire.” Heures de Marguerite de Valois, BNF, NAL 83, folio 1v. Lecoq, François Ier, 396–97. Middlebrook, “Tout mon office,” 1120.

[27] Verdier, Catalogue, xxi.

[28] Verdier, Catalogue, 46–50; Wardropper, Limoges Enamels, 29 (cat. 4).

[29] The portrait of Eleanor is located in the musée national de la Renaissance in Écouen (inv. Cl 2520). Though Eleanor’s portrait is the earliest of Limosin’s portrait enamels with a secure date (the date is inscribed next to the artist’s signature), Limosin may have painted other portraits earlier in the 1530s, including one that likely depicts a Reformer that was in the collection of the Wernher family at Luton Hoo in Bedfordshire (now part of the Ranger’s House collection). See Baratte, Leonard Limosin, 43.

[30] Sophie Baratte, Les Emaux Peints De Limoges (Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 2000), 94, 114. Ydeux and Pénicaud’s enamels are Louvre OA 969 and OA 4003 respectively. A nineteenth-century enamel, Triptych: The Lineage of St. Anne, in The Frick Collection (1916.4.12) may also highlight the prevalent influence of The Virgin and the Cradle print on Renaissance Limoges enamelers. That a nineteenth-century forger would choose to represent this design indicates that painted enamels derived from Raimondi’s engraving were widespread during the Renaissance period. Ian Wardropper attributes the central grouping of the Holy Kinship in The Frick’s Triptych to an engraving by Marco Dente of the same design. See Ian Wardropper and Julia Day, Limoges Enamels at the Frick Collection (New York: The Frick Collection, 2015), 73.

[31] A mid-sixteenth-century date of execution also justifies the identification of the sitter in the Walters enamel portrait as Marguerite (d. 1549), rather than the predeceased Anne of Brittany (d. 1514) or Louise of Savoy (d. 1531). While posthumous portraits were commissioned in sixteenth-century France, these commemorative likenesses were more often executed closer to the date of the sitter’s death.

[32] This letter is translated in Barbara Stephenson, The Power and Patronage of Marguerite de Navarre (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), 145.

[33] For example, in a Chanson titled “Autres pensees faites un mois apres la mort du roy” (Other thoughts a month after the king’s death), Marguerite describes her suffering, writing “Body and soul are heavy with grief,/ So much so that they are turned into suffering.” See Marguerite de Navarre, Spiritual Songs, in Selected Writings: A Bilingual Edition Marguerite de Navarre, ed. Rouben Cholakian and Mary Skemp (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008), 287. Marguerite composed the Chansons after moving to the convent of Tusson. See Pierre Jourda, Marguerite d’Angoulême, Duchesse d’Alençon, Reine de Navarre (1492–1549) (Paris: Champion, 1930), v1, 315; Patricia F. Cholakian and Rouben C. Cholakian, Marguerite de Navarre (1492–1549): Mother of the Renaissance (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), 270–71; Elizabeth Chesney Zegura, Marguerite de Navarre’s Shifting Gaze: Perspectives on Gender, Class, and Politics in the Heptaméron (New York: Routledge, 2017), 55. On the Comedie and Le Navire, see Verdun Saulnier, Le thèâtre profane de Marguerite de Navarre (Paris: Droz, 1963), 207; Cholakian and Cholakian, Marguerite, 276; Abel Lefranc, Les dernières poésies de Marguerite de Navarre (Paris: Armand Colin, 1896), 385–86.

[34] Louise died in 1531, and several of Francis’s children died before him. Princess Charlotte died in 1524; Francis III died in 1536; Princess Madeleine of Valois died in 1537; Charles II died in 1545.

[35] In particular, Marguerite and Henri clashed over the marriage proposals for her daughter Jeanne d’Albret (1528–1572). See Cholakian and Cholakian, Marguerite, 282–86.

[36] Jourda, Marguerite d’Angoulême, vol. I, 313-17. The French historian Pierre de Brantome (1540-1614), who spent his childhood at the court of Francis I, would describe Marguerite’s isolated lifestyle and fervent pattern of devotion after the death of her brother: “Aprez la mort du Roy son frere, qu’on appellee Tusson, où elle y fist sejour, sa quarantayne, tout ung este, et y bastit ung beau logis, souvant on l’a veu faire l’office de l’abesse et chanter aveq’ les Religieuses en leur Messes et leur vespres (After the death of her brother the King, she stayed there which is called Tusson, and built beautiful lodgings there, we often saw her performing the office of the abbess and singing with the nuns in their masses and their vespers).” Brantôme, Recueil des dames, poésies et tombeaux (Paris: Gallimard, 1991), 182.

[37] Sotheby’s New York: ‘Cyril Humphris Collection, part 1: European Sculpture and Works of Art’, 10 January 1995.

[38] Verdier, Catalogue, 104.

[39] Orth previously suggested that the sitter in the Kofler-Truniger portrait may be Louise, and proposed that the enamel may have been intended as a gift for Marguerite. Orth, “An enamel,” 3. However, it seems more likely that the sitter portrayed in all three enamels is named Margaret.

[40] “MEDATRIX OMNIVM ET FONS VIVVS IN DESINEN… ORE COPIOSE FVNDEN… MARIA TE QVESO (D)ULCISSIMA MATER PER ILLAN TVRBATION…QVA (Mediator of all and living fountain…unceasingly pour out…Maria, I beseech thee, sweetest mother, through this disturbance.)”

[41] See Crépin-Leblond, Une Reine, 124; “Medallion,” The Victoria and Albert Museum (no. 7912-1862), http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O128865/medallion-limosin-leonard/; see also “Roundel of a Portrait with a Noblewoman,” Sotheby’s (2016), http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2016/treasures-l16303/lot.3.html.

[42] The woodcut is thought to be based on a drawing by Holbein. See Christian Rümelin, “Icones,” in Hans Holbein the Younger: The Basel Years 1515–1532, edited by Christian Muller (New York: Prestel, 2006), no. D. 22, 478. Holbein adapted his woodcut from Raphael’s design for Moses on Mount Sinai, a fresco (competed around 1519) in the Vatican Logge that was executed by Perino del Vaga (1501–1547). Although the Icones were initially executed during the mid- to late 1520s, they remained influential long after this period. See Stephanie Buck, “International Exchange: Holbein at the Crossroads of Art and Craftsmanship,” in Hans Holbein: Paintings, Prints, and Reception, ed. Mark Roskill and John Oliver Hand (Washington, DC: The National Gallery of Art, 2001), 59–63. As a golden calf is not represented in Holbein’s rendering of Moses, the presence of this idol in the background of the enamel’s reverse image is most likely derived from Salomon’s woodcut, which was published in the Quadrins historiques de la Bible, and inspired the designs of many Limoges enamelers active during the third quarter of the sixteenth century. See Peter Sharratt, Bernard Salomon: illustrateur Lyonnais (Paris: Librairie Droz, 2005), 205–6. See also two tazze (44.199 and 44.144) in the Walters Art Museum by Jean de Court (active ca. 1541–64), both of which depict Moses destroying the tablets of the law.

[43] Crépin-Leblond, Une Reine, 124.

[44] Crépin-Leblond, Une Reine, 124.

[45] Roundel of a Portrait with a Noblewoman,” Sotheby’s (2016), http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2016/treasures-l16303/lot.3.html.; “Medallion,” The Victoria and Albert Museum (no. 7912-1862), http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O128865/medallion-limosin-leonard/ .

[46] “Medallion,” The Victoria and Albert Museum (no. 7912-1862), http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O128865/medallion-limosin-leonard/