The figures in the Walters’ Abduction of Helen series, painted for the wedding of Caterina Corner, are depicted in magnificent fifteenth-century Italian silks.[1] The most splendid of these were created with applied molded tin foil, textured to simulate the gold and silver threads of sumptuous brocaded velvets (fig. 1). The technique used to depict these fabrics in painting and sculpture is known today by various terms—tin-relief textiles or applied relief brocade, brocados aplicados (Spanish), brocarts appliqués (French)—but most commonly by the German Pressbrokat.[2] The cost of the actual fabrics depicted in these paintings would have been enormous, demonstrating the wealth and high social status of the family associated with the commission. In parallel with the growth of the luxury textile industry during the period, the technique was used in painting and sculpture throughout much of Northern Europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, but it rarely appears in Italian works of art. The application of over 13 square feet (1.2 square meters ) of Pressbrokat in the Abduction of Helen series is therefore an unusual and significant component of these paintings. The material study of the Pressbrokat on these paintings adds to the understanding of the collaborative creation of the paintings, supporting the localization of their production to the Veneto, and provides important contributions to the body of published technical studies on the topic.

Location of Pressbrokat, gold and silver brocades, distinguished as yellow and gray respectively, in the Abduction of Helen series. Dario di Giovanni (ca. 1420–before 1498) and collaborators, The Abduction of Helen spalliere. Tempera and Pressbrokat on spruce. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, bequest of Henry Walters, 1931. Left: The Departure of Helen and Her Entourage for Cythera, 60 × 94 3/16 in. (152.4 × 239.2 cm), acc. no. 37.1178; center: The Abduction of Helen from Cythera, 60 3/8 × 116 1/4 in. (153.3 × 295.3 cm), acc. no. 37.1179; right: The Reception of Helen at Troy, 60 1/16 × 96 1/8 in. (152.6 × 244.2 cm), acc. no. 37.1180

Until the twelfth century, luxury silks, because of their cost, were limited to religious and lay elites, but as trade, banking, and industry in Italy created a new, affluent class, the market for fine textiles, documented through paintings, inventories, and datable textiles, had expanded by the second quarter of the fourteenth century.[3] Though the textiles would have been prohibitively expensive for most consumers, demand for luxury silks was so high that sumptuary laws were enacted in several Italian cities, attempting (albeit with little success) to control who wore silks, as well as how often silks could be worn.[4]

The silks imported into Italy were mainly of Byzantine origin until the first half of the thirteenth century; subsequently, larger quantities of silks were imported from the east, primarily from Islamic lands.[5] In addition, new kinds of luxury silk textiles brought into Italy from Central Asia, Persia, and Syria “generated an evolution in taste and fashion which rapidly spread from Italy to the entire Latin west.”[6] These textiles, referred to in Italy as panni tartarici, or Tartar cloths, often combined Chinese, Central Asian, and Islamic motifs, and included cloth woven with gold thread. Weavers in Lucca, Venice, and Florence started imitating these imported luxury silks and over time developed local, proprietary patterns. By the end of the fourteenth century, Italians were producing silk velvets, “the most desirable luxury fabric.”[7]

The materials needed to produce these lavish textiles, including large quantities of raw silk, dyes, and metallic threads, were expensive and required laborious preparation. To produce velvet, a second warp (the longitudinal thread) was introduced into the weave, necessitating large quantities of silk thread to create the small loops of pile that, left uncut or cut, produced different textures and luminous effects. Brocading required the introduction of supplementary wefts (the horizontal or transverse thread), often using gold or silver thread. These threads were made by gold-beaters, or battilori, who wrapped strips of beaten metal foil around silk or linen threads.[8] The costliest velvets incorporated looped wefts of metallic thread, necessitating large quantities of gold or silver thread to create localized patterns or broad expanses.[9] Increasingly intricate designs of color and texture were created using various dyes, pile heights, and metallic threads.

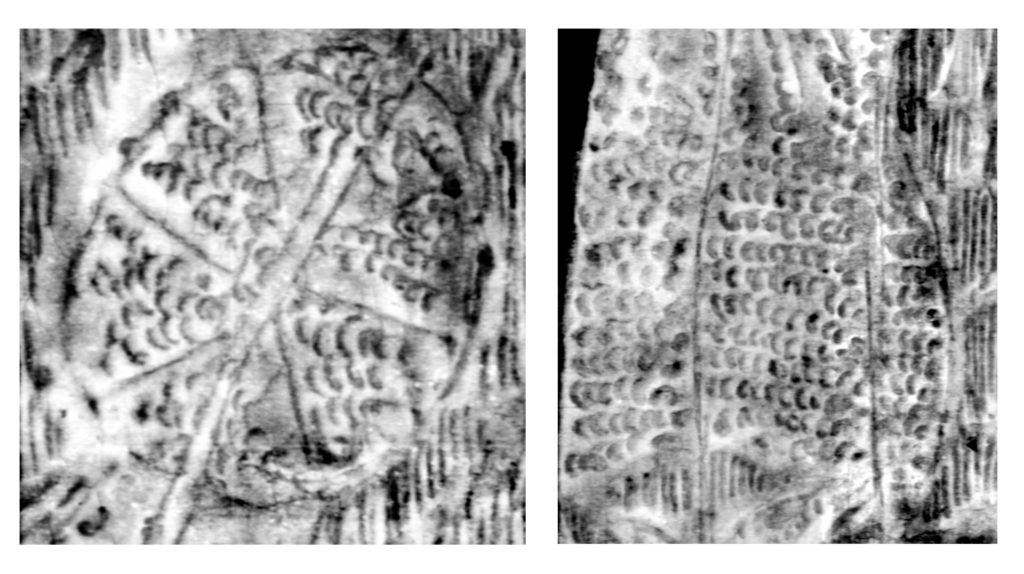

Early designs included geometric patterns, animals, birds, and plants, at first small and densely patterned, evolving into larger patterns with surrounds of various roundel shapes. By the fifteenth century and continuing into the early sixteenth century, most of the textiles produced in Italy incorporated a “pomegranate pattern” which comprised numerous stylized natural forms, including pomegranates, acanthus, thistles, pinecones, pineapples, lotus flowers, palmettes, or artichokes (fig. 2).[10] Pomegranate fruit, in addition to their decorative qualities, had symbolic meanings originating in the Middle East, including fertility and regeneration.[11] Italian silks, with their imaginative patterns and fine quality, were highly sought-after in Europe and were even exported to Mamluk elites in Egypt and Syria.[12] Venetian silks in particular were highly valued in Ottoman and Mongol territories.[13] Consequently, the production of luxury silks became a crucial part of the economy in several northern Italian city-states.

Left: Fifteenth-century Venetian voided silk velvet with supplementary gilt-wrapped threads exhibiting an undulating “pomegranate pattern.” The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, gift of Laurence and Isabel Roberts, 1988, acc. no. 83.742; Center and right: Detail of the Departure under visible light (left) and in grayscale with patterns enhanced (right)

Paralleling developments in the textile industry, representations of luxury silks became common in paintings and sculpture throughout Europe starting around the end of the thirteenth century. Contracts between artists and patrons sometimes even specified the type of cloth to be depicted.[14] To imitate the glimmer of silk and the shine of metallic threads, artists used several different techniques, including glazing transparent paint over metal leaf, applying localized gilded designs onto painted backgrounds (mordant gilding), and scratching designs through paint layers to reveal gilding below (sgraffito). Woven textures were simulated by tooling gilding layers or applying relief made from gesso, known as pastiglia, that was subsequently gilded or painted.[15] A specialized technique, Pressbrokat, distinguished by its dimensional texture using molded tin foil to simulate woven textiles, became an especially convincing and popular method to represent highly valued textiles in works of art; surviving examples range from around 1420 to 1540.[16] Throughout much of Western and Central Europe, Pressbrokat was applied to polychrome sculpture, panel and wall paintings, and interior architectural elements such as niches and ceiling coffers.[17]

The materials and techniques associated with Pressbrokat are a continuation of earlier methods using molded tin with a relief mass to imitate solid precious metal ornament, seen, for instance, on the applied glazed tin forms intended to imitate gold on late twelfth-century French sculpture from the Auvergne region, such as the Montvianeix Virgin and Child and the Morgan Madonna now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[18] Tin-relief and other relief ornamentation techniques such as pastiglia and casting replaced much costlier, laborious, and heavier die-formed or repoussé sheet-metal ornaments sometimes attached to wall paintings, panel paintings, and sculpture up to the thirteenth century.[19] In addition to a growing body of technical analysis of surviving examples of Pressbrokat, two treatises, roughly contemporary with the Abduction of Helen paintings, describe related processes for manufacturing tin-relief ornament that are relevant to understanding the materials and methods used in making Pressbrokat: Cennino Cennini’s treatise Il libro dell’arte, composed around 1400, and a later compilation, the Liber illuministarum, written in Tegernsee, Bavaria, around 1500.[20] The former describes techniques for producing relief decorations such as “figures, animals, devices (flowers, stars, roses, and every kind that your imagination desires)” before the known introduction of Pressbrokat;[21]the latter provides instructions on making, gilding, and applying tin-foil relief, but it does not describe the making of the mold or specify whether it was to imitate textiles.

To achieve the distinguishing appearance of a textile weave, the manufacture of Pressbrokat began with a smooth-surfaced mold, probably made of stone or metal or possibly fine-grained wood.[22] Molds facilitated the multiple copies of motifs that were necessary to simulate the repeat patterns of brocades. Lines, often straight and parallel, were incised into the mold, imitating the metallic thread floats of a brocade design. While in actual textiles, brocaded threads are inserted as supplemental horizontal wefts, in Pressbrokat threads often run vertically or obliquely, probably to take advantage of the way the work would be viewed; as one moved across a room, the raised vertical lines appeared to flicker in the changing angles of light.[23]

Once incised, the mold was probably prepared with a release layer to aid in separating the formed tin from the mold (Cennini recommends greasing the mold with fat or lard); next, a thin sheet of tin foil was laid into the mold, followed by wadding. Both Cennini and the Liber illuministarum recommended using dampened tow, or coarse fiber, as wadding material to protect the tin as it was beaten into the carved interstices of the mold, creating a reversed profile of the pattern such that incised lines in the mold resulted in lines proud of the final surface. A bulked material, or fill mass, was then applied to support the molded foil. This fill mass flowed into the incised lines and recessed design then hardened. While Cennini recommended gesso grosso mixed with glue, the Liber illuministarum recommended a mixture of chalk, pitch and dilute glue. Combinations of materials including warmed wax, natural resins, gums, drying oils, and proteinaceous binders such as egg or animal glue, observed in technical studies, were all used as components of the fill mass. Additives such as chalk, gypsum, pigments, or fibers were used to modify the fill’s viscosity and drying time. Factors to consider when devising modifications to the fill probably included the ambient working conditions (primarily the temperature and relative humidity), the complexity of the form to which the Pressbrokat would be attached, the size of the Pressbrokat sheets and the potential complexity of lining up continuous designs with abutted sheets of Pressbrokat. While a somewhat slower drying time might have offered beneficial control of application in some of these instances, too slow a dry time could be problematic, especially if the Pressbrokat was applied to an object vertically. The specific composition of the fill would have been an artist’s or workshop’s guarded secret, and it might change over time depending on the availability of particular materials or refinements in techniques. The fill was important as it solidified the form of the molded tin foil and provided a flat surface to anchor the tin to the intended support; the materials of the fill and their aging characteristics could have implications for preservation of the Pressbrokat and once identified, could be used to compare and potentially associate makers as more technical studies are undertaken.

Once the fill material had cured, the tin foil, reinforced by the fill mass, was lifted from the mold. The parallel lines incised in the mold produced raised lines of tin that mimicked metallic threads. Continuously joined full sheets or smaller custom-shaped pieces were adhered to the intended surface with the textured tin metal exposed. Cennini recommended ship’s tar or pitch as an adhesive, while the Liber illuministarum suggested hide glue or a paste of flour and powdered resin, or with a “mordant,” in this case an oil-bound mixture containing lead pigments.[24]The shiny surface was often enhanced with applied gold or silver leaf, coated with a transparent yellow-tinted glaze to imitate gold, or coated with an untinted varnish to imitate silver.[25] These coatings also slowed the metal’s corrosion. Finally, paint was applied locally to imitate designs of cut velvet pile.

Pressbrokat can be difficult to identify, due in part to misunderstandings of the processes and materials.[26] The presence of tin might be overlooked due to its propensity to corrode and deteriorate.[27] Further confusion might be attributed to an early technical study of Pressbrokat that mistakenly described the technique as created using sheets of molten wax that were “stamped with a die”;[28] the tin, probably the material that was described as a “blackish unidentified film over the stamped gesso,” was not identified. [29] Discrepancies regarding terminology, moreover, make the confirmation of the technique difficult. Ornament using the same technique with molded tin and a fill mass but used for effects other than imitating textiles is still called Pressbrokat in Italy.[30] Depictions of textiles using materials other than applied tin relief are also sometimes described as Pressbrokat; however, the presence of tin is a defining characteristic of the technique.[31] Adding to the confusion, more than twenty different terms in various languages are used to describe the technique of imitating textiles, usually but not always brocaded, in relief by use of an incised mold, tin, and a bulked fill mass.[32]

The geographical origins of Pressbrokat are not known, but some of the earliest examples appear in panels dated around 1415–1430 from Norwich, Hamburg, Berlin, and Cologne.[33] Other early instances of the technique occur in sculpture produced in Brussels and in Early Netherlandish paintings.[34] The production of applied relief brocade spread south through the Low and Germanic countries, across the Alps to northern Italy, east to Lesser Poland and Transylvania, west to France, Spain and Portugal, and north to England, Wales, and Sweden.[35] Surviving works suggest that Pressbrokat was used most extensively in Germany. It is likely that specialized craftsmen, distinct from painters, produced Pressbrokat and disseminated the technique through migration and travel.[36] Because of Venice’s renown as a center of cultural and commercial exchange, it attracted artists and artisans from German cities, who probably brought the technique of Pressbrokat to Venice.[37]

Examples of Pressbrokat in Italian works are rare; surviving examples are limited to northern regions of Italy. Certainly Italian artists incorporated relief effects into works of art, but tin-relief textiles were limited to the Italian north, mainly southern Tyrol but also Lombardy and the Veneto.[38] A work believed to be part of the same commission as the Abduction of Helen series, The Garden of Love, in the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, similarly incorporates areas of Pressbrokat, but it has been heavily restored, making comparisons challenging.[39] Photographs of another painting attributed to Dario di Giovanni, Maiden with Unicorn, in the Christian Museum, Esztergom, Hungary, suggest that only some of original Pressbrokat survives, largely the red fill mass with vestiges of tin.[40] Given the evidence for artistic exchanges between Dario di Giovanni and the workshop of Antonio Vivarini (see Spicer in this volume), of particular interest is the Pressbrokat on a triptych on canvas from 1446 by Vivarini and Giovanni D’Alemagna: The Enthroned Madonna with Four Angels and the Four Fathers of the Church, in the Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice.[41] The presumably German-born Giovanni is often credited with the incorporation of relief brocade here. Localized areas of Pressbrokat may also appear in other paintings from this workshop, but analyses are scant and inconclusive.[42] Early representations of textiles by Pisanello in frescoes in Verona and Mantua incorporate a similar appearing texturing effect, but not with made pre-molded tin with a cast fill mass as in Pressbrokat.[43]

At the end of the fifteenth century and into the next century, in two Venetian provinces just south of the Alps, Belluno (part of the Republic of Venice after 1404) and Friuli (after 1420), artists from Venice and Germany worked in close contact, and some workshops frequently incorporated applied brocade in their altarpieces.[44] Several instances of the technique are found in altarpieces produced by a workshop in Udine, where Dario di Giovanni resided early in his career.[45]

Pressbrokat in the Abduction of Helen Spalliere

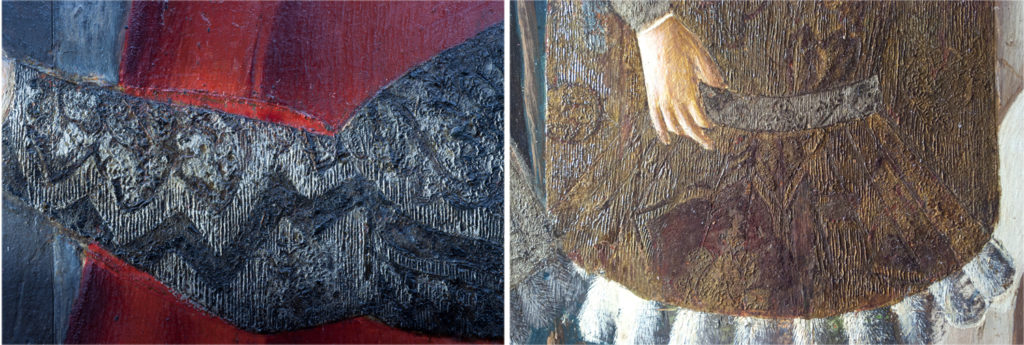

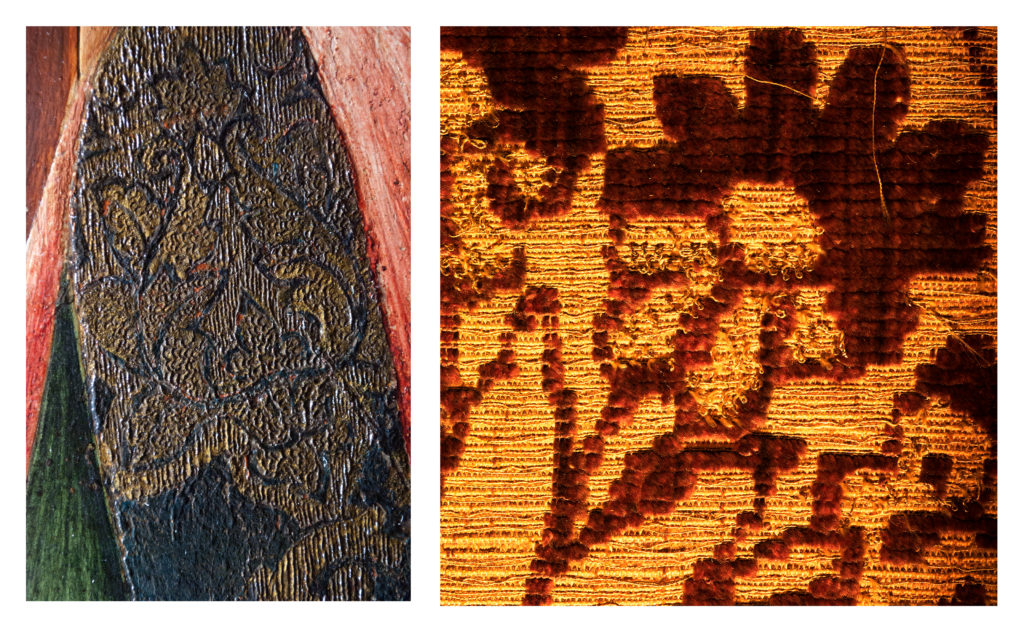

Nearly all of the figures in the Walters’ Abduction series wear garments created with Pressbrokat, ranging from full-length dresses and outergarments to shorter tunics and smaller localized areas of belts, sleeves, and collars (fig. 3). Gold and silver brocades were alternated for decorative effect and were interspersed with painted (non-brocaded) textiles. Prominently featured are the popular “pomegranate designs” on vertical undulating branches (see fig. 2). Two figures, a female in The Departure of Helen and Her Entourage for Cythera and a male on The Abduction of Helen from Cythera have Pressbrokat ornamented at the edges with dagging, the fashion of cutting edges into shaped forms. Usually associated with fashion of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, its use here might have been intended to suggest an “‘antique’ and Eastern flavor” as, for example, in the mantel worn by a follower of the three kings in a slightly earlier Venetian painting: The Adoration of the Magi by Antonio Vivarini and Giovanni d’Alemagna in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin (fig. 4). [46]

Details of a Pressbrokat sleeve from the Reception (left) and a tunic and belt from the Departure (right)

Dagging in a detail from the Abduction (left) and a detail from Antonio Vivarini and Giovanni d’Alemagna, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1440–1445, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin (right)

While most of the materials of the Pressbrokat on the Walters paintings have survived through the centuries, much of the Pressbrokat’s original intended appearance has altered due to the corrosion of the metal and subsequent restoration. When the Walters’ conservation treatment of these paintings began in 2010, metallic surfaces that were intended to glimmer were dark and dull. X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) confirmed the presence of tin throughout the Pressbrokat. Scanning electron microscopic analysis (SEM) and electron dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) of a cross section of the Pressbrokat extracted from the Reception detected a thick layer of tin-rich material, suggesting that the original metal foil had oxidized and converted to tin oxide, the mineral cassiterite, now measured as a discrete layer about 30 microns (0.0012 in.) thick. Complete corrosion of the tin metal foil into the tin oxide is estimated to take approximately 100 years.[47]

Consequently, much of the Pressbrokat in the Abduction of Helen paintings had been extensively covered with restoration material. Before the paintings entered the Walters’ collection, restorers applied metallic paint to refresh the lost metallic luster, but with time, the brass paint applied to the “gold” textiles had oxidized into a dull brown finish.[48] Examination with x-radiography and raking light revealed the extent of loss to the tin. While restorations sometimes simply reinforced the original patterns, in severely damaged areas the entire design had been reworked. Restoration overpaint could not be removed during recent conservation treatment without damaging the delicate underlying Pressbrokat (see French and Gordon, “Conservation,” in this volume”). XRF examination detected no evidence of gold or silver leaf on the brocade surfaces, indicating that the original intent was to depict gold brocades by using translucent yellow coatings and to depict silver brocades by leaving the tin unfinished or by applying uncolored varnish coatings. The extensive metallic paint restoration precluded the analysis of any original applied glazing or toning on the top of the tin. Ingrid Geelen and Delphine Steyaert’s extensive survey of applied relief brocade from Northern Europe suggests that, with the exception of a few wall paintings, Pressbrokat was usually gilded with gold leaf, but surveys of Tyrolean works show that these were in fact sometimes coated with yellow glaze (vermeil).[49] In the case of the Walters’ gold brocades, the choice to apply a yellow glaze rather than gilding might have been driven by cost, but it may have also been influenced by methods used in nearby Tyrol.

Subtle seams noted in large areas of brocade reveal abutted sheets of Pressbrokat and indicate that the molds used for the Abduction of Helen series were quite large: expanses as large as 36 by 28 cm (14 1/8 × 11 in.) were found. In comparison, Geelen and Stevaert’s study of Pressbrokat produced in Northern Europe found that most molds were smaller than 21 square centimeters (8 1/4 square in.).[50] However, the use of large molds (approximately 31.5 × 28.5 cm) has been detected on Italian altarpieces scattered throughout the Fruili-Venezia Giulia region,[51] as well as on altars in Prague and Rothenburg.[52] On each of the Walters’ panels, the largest individual sheets of Pressbrokat were reserved, probably deliberately, for Helen’s dress. Using larger sheets of Pressbrokat was not only more time-efficient but also made it possible to display larger textile motifs with fewer potentially problematic seams.

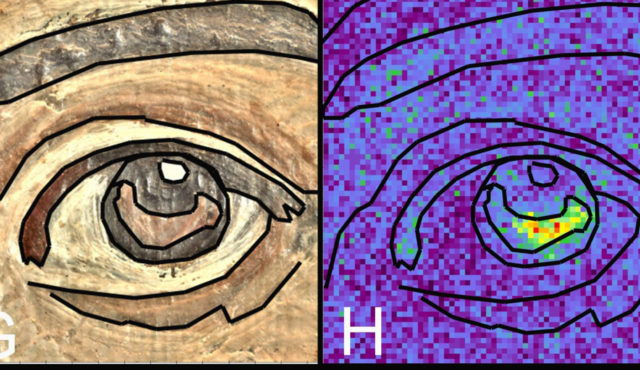

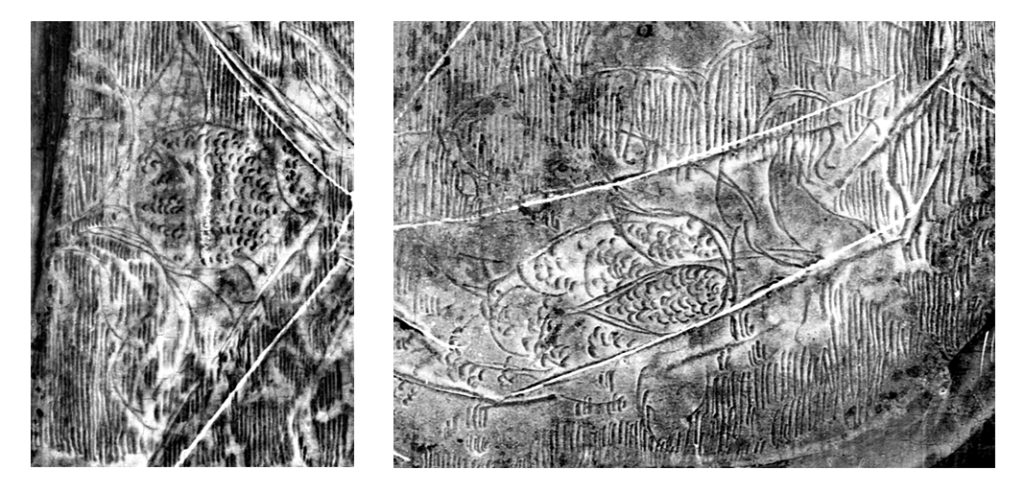

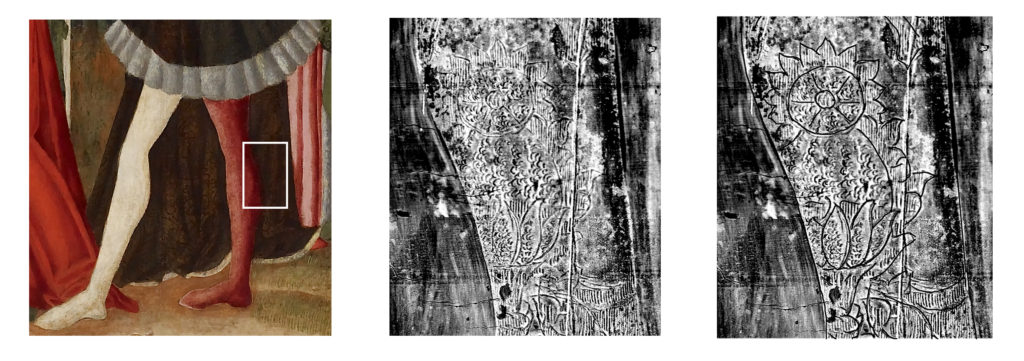

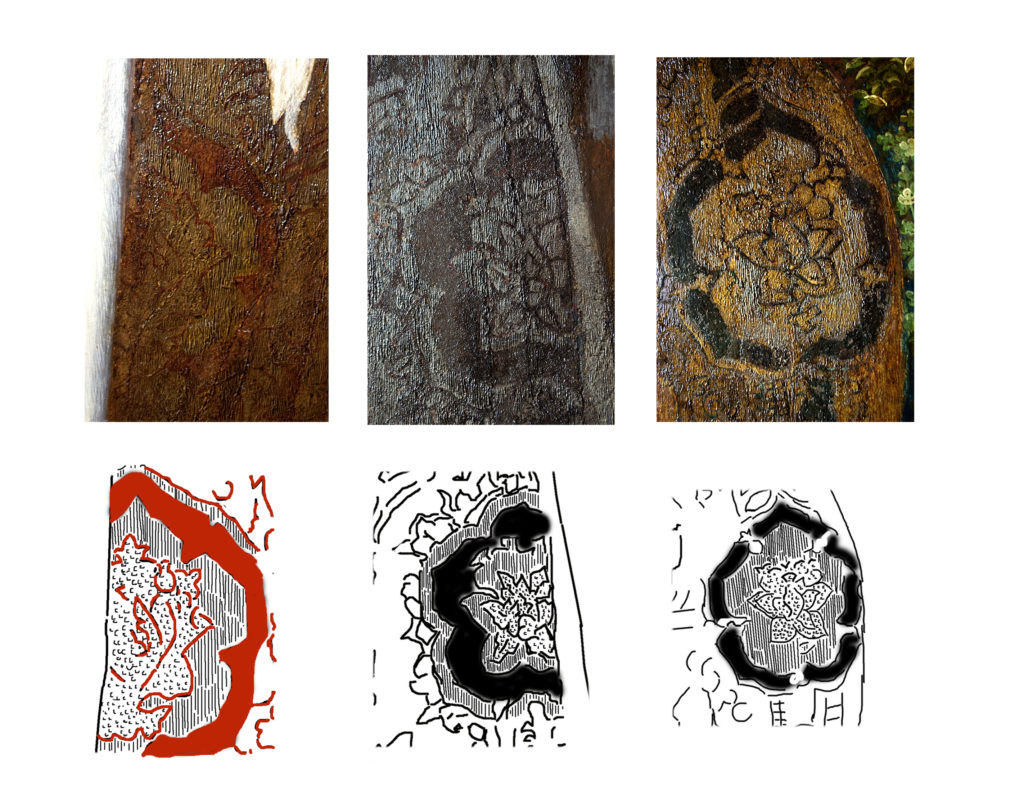

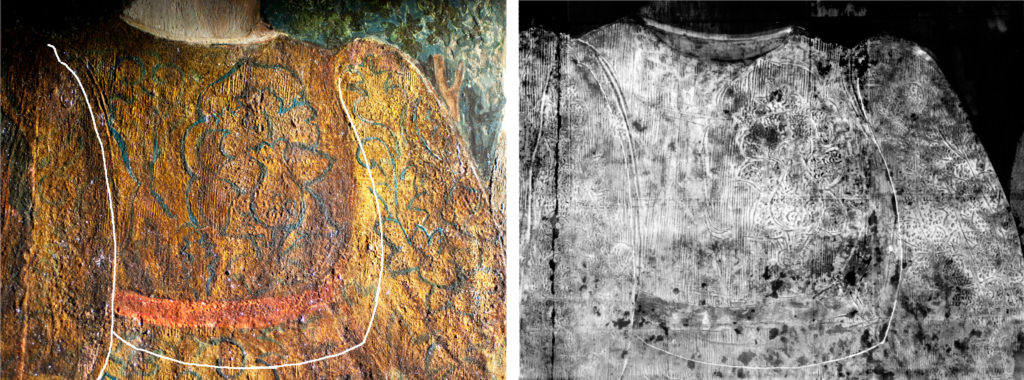

Examination with X-radiography clarified the original designs, now obscured with restoration material or otherwise hard to discern (fig. 5). Motifs include pinecones, thistles, twisting acanthus leaves, and flower buds (figs. 6 and 7). There are also curious stylized pomegranates with their usually upright crown-like calyx turned to face the viewer (fig. 8). These resemble pomegranates in paintings by the Venetian Michele Giambono (active 1420–1462) as seen on the textile depicted in the background of his Madonna and Child, ca. 1450 (fig. 9) and on the shoulder of Portrait of a Man, 1432–34 (fig. 10). A similar form appears on the robe of the kneeling king on the Adoration of the Magi panel from Hans Multscher’s (ca. 1400–1467) Wurzach Altarpiece (Staatliche Museen, Berlin).

Detail of Helen’s cloak from the Reception with Pressbrokat designs;

original design concealed by restoration paint (left), design revealed with x-radiograph (horizontal aluminum channel on reverse interrupts image with a white line) (center) and line tracing of the x-radiograph (right) (drawing extended slightly across horizontal interruption)

X-radiograph details of Pressbrokat from the Abduction showing a thistle (left) and flower bud (right)

Left: a pomegranate “flower” (hypanthium); center: x-radiograph of a Pressbrokat design from the Abduction; right: x-radiograph with overlaid tracing

Left: Detail from the Abduction of a “pomegranate” with its calyx turned to face the viewer; center: Pressbrokat design in x-radiograph; right: x-radiograph with overlaid tracing.

Michele Giambono (active 1420–1462), Madonna and Child, ca. 1445–1462.Tempera on panel, 22 × 18 1/2 in. (56 × 47 cm). Museo Correr, Venice, inv. no. 1083. Detail: Photograph Gianluca Poldi, Segrate (MI), Italy

Michele Giambono (active 1420–1462), Portrait of a Man, 1432–34. Tempera and silver on panel, 20 7/8 × 15 3/4 in. (53 × 40 cm). Palazzo Rossa, Genoa

Care was taken to continue the designs across the joins of individual sheets of Pressbrokat. Motifs are occasionally depicted in perspective, following the form of the body, and designs change direction at major folds in the garments, such as where the trains of the dresses drape on the floor. Given the use of molds in the manufacture of Pressbrokat, one might expect to see the same designs recurring, but the designs only rarely repeat from one garment to another: different figures wear slightly different textile designs.[53] The lack of noticeable repeats seems to indicate that the focus of the technique in this case was to artfully simulate the texture of luxurious velvet fabric enhanced with metallic threads rather than speed of fabrication.

X-radiograph details reveal that the textile patterns were incised onto the mold’s surface with a very loosely drawn, sketch-like execution, often retraced with slight adjustments (fig. 11). This loose approach appears very different from other examples of Pressbrokat imaged with X-radiography, where the lines were more deliberate and neatly applied.[54] Also noted in x-radiograph details, the parallel lines mimicking metallic thread tend to have a characteristic slight curve to the right at the top and bottom (see figs. 5, 6, and 11). The lines vary in length, with the longest measuring about 1 1/8 inches (3 cm). A “thread count” of the resulting raised lines in the tin averaged 13–16 lines per centimeter in the Abduction and the Reception, while in the Departure the count, at 18 lines per centimeter, averaged slightly more.

Sketch-like drawing of textile motifs visible in x-radiograph of Pressbrokat detail from the Reception

The brocades were additionally textured with massed, half-rounded c-shaped marks, sometimes connected to each other in continuous loops. These marks are meant to imitate small loops of metal thread, or bouclé (figs. 12 and 13). In other published instances of applied brocade with bouclé effects, the loops of metallic threads are simulated with small, regularly shaped raised dots. According to Geelen and Steyaert’s study, the earliest examples of these small raised dotsseem to date to sculpture from the1460s in Brussels and Germany.[55] In an early sixteenth-century example of Pressbrokat on Giovanni Martini’s altarpiece in the Church of San Stefano at Remanzacco, Udine province, bouclé is imitated by zig-zag lines.[56] Venetian artists imitated these supplemental weft loops in various other ways as well; in Giambono’s Madonna and Child of 1450, Museo Correr, Venice, small ‘c’s’ were scratched into an almost dry layer of paint over gilding: a technique similar to sgraffito (see fig. 9).[57] Vivarini and Giovanni D’Alemagna imitated bouclé by locally tooling gilding layers in the 1443 Madonna and Child Enthroned (fig. 14). In the signature work by an artist of Greek birth working primarily in Venice, Antonio da Negroponte, Madonna and Child Enthroned (ca. 1455, San Francesco della Vigna, Venice), the relief effect of the brocade, including tightly clustered metallic loops, was apparently produced by tooling the ground before gilding.[58]

Seamless looping design visible in x-radiograph details from the Abduction

Left: straight and looped metallic threads and velvet imitated in a detail of brocade from the Departure; right: detail of a 15th-century Venetian textile (Walters Art Museum, acc. no. 83.742)

Antonio Vivarini (ca. 1415–ca. 1480) and Giovanni d’Alemagna (1399–1450), Madonna and Child Enthroned, ca. 1443. Tempera and pastiglia on panel, 58 11/16 × 26 3/8 in. (149 × 67 cm). Church of San Tomaso Becket, Padua, on deposit at the Museo Diocesano, Padua

The fluidity of the sketch-like design, the tightly spaced striated lines with their curved ends, and the seamless loops of the bouclé indicate that the surface of the mold in this instance was fairly soft and easy to incise.[59] Rather than stone or wood, oiled lead molds, used in past reconstruction attempts, could be a possible source.[60] An intriguing suggestion by conservator Nicoletta Buttazzoni that designs might have been etched onto copper or iron molds using acid also seems possible in this instance.[61]

In contrast to the textured areas, the Pressbrokat includes smooth, flat areas intended to simulate fields of plain-cut velvet, such as the wide ogee-shaped borders around the large pomegranate forms (fig. 15). These areas are painted with blue (copper-rich azurite) or red (mercury-rich vermillion) opaque paint, indicated by XRF analyses, probably to imitate indigo and red lake dyes used with textiles. In one instance, white paint was used to delineate forms on a gold brocade on the sleeves of a female figure in the Departure. The figure of the priest in the temple of Venus in the Abduction wears a red hat, a kamelaukion, textured to imitate varying piles of unbrocaded velvet.

Details of texture and pattern variations of pomegranates in three dresses from the Departure (raking light above, line tracings of x-radiograph details below)

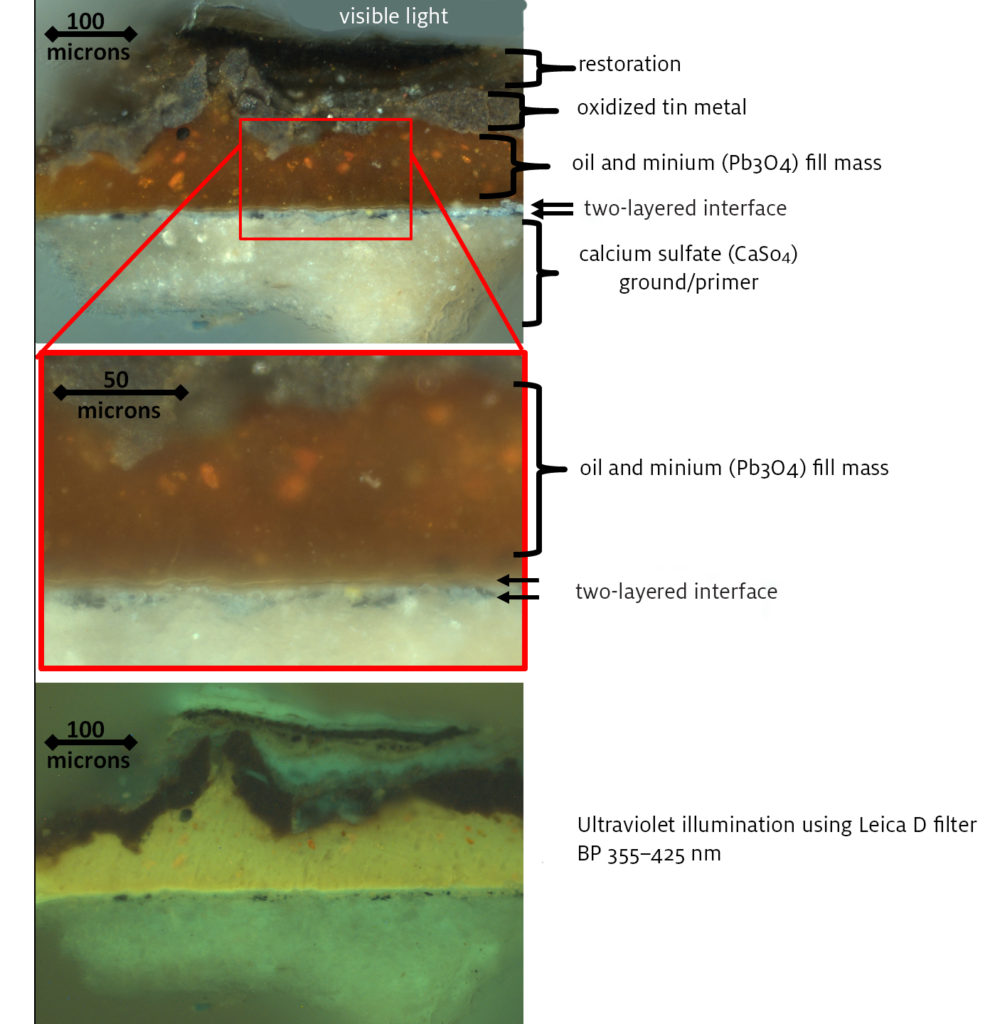

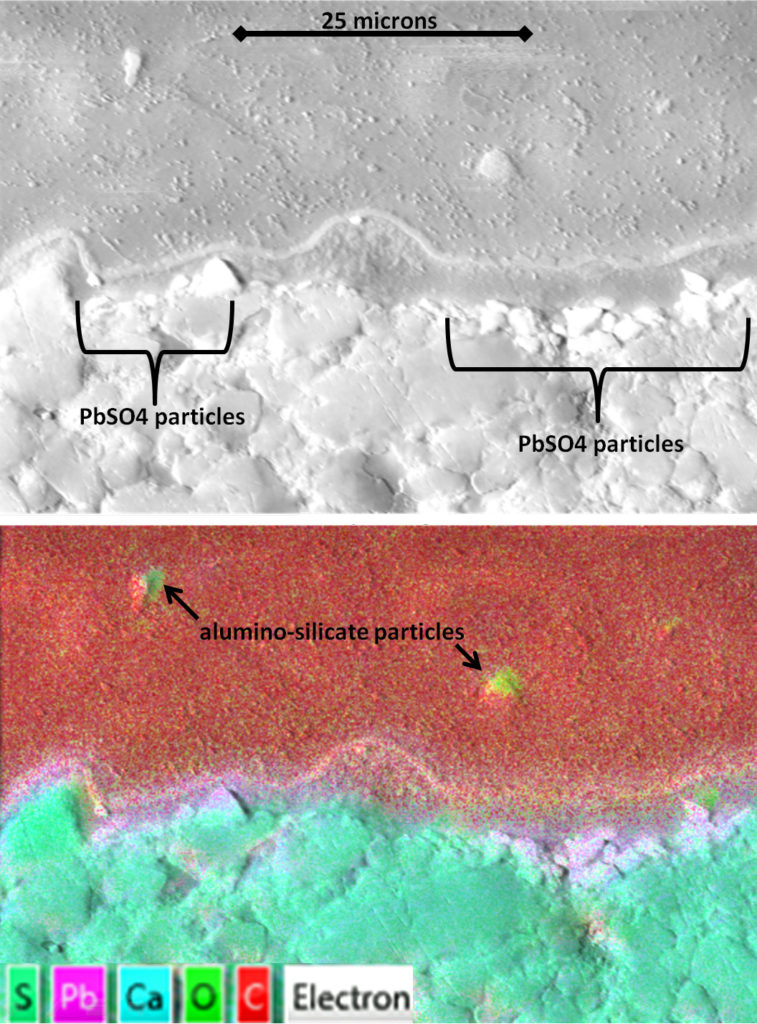

An array of methods was used to determine the composition of the orange-toned fill mass supporting the tin relief. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) suggested that it is composed of a complex mixture of drying oil with lead soaps such as palmitate or stearate, and kaolin and resin (est. pine). Scanning electron microscopy / energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) confirmed the presence of only a few kaolin-like alumino-silicates and established that the fill mass contained a high quantity of lead (see fig. 16). FTIR using attenuated total reflectance (ATR) confirmed the presence of a drying oil in the fill mass. Raman spectroscopy identified the red lead oxide called minium (Pb3O4). As a siccative, minium would have accelerated drying and added a warm red tone underneath the tin. Analyses using pyrolysis gas chromatography with mass spectrometry (pyGCMS) provided further confirmation of the presence of an aged drying oil, with the presence of dehydroabietic acid, and colophony (rosin), suggesting the use of a pine-based ingredient, such as Venice turpentine, as a diluent. Additionally, polarizing light microscopy (PLM) identified segmented bast fiber, possibly hemp or linen from shredded paper or textiles, perhaps added to bulk and strengthen the fill mass. Other studies have found fibers only occasionally in the fill mass for brocades, although they might be easy to overlook. Fibers were tentatively identified in the gesso and glue fill mass in the Pressbrokat on Giovanni Martini’s altarpiece at Remanzacco.[62] They were also noted in Pressbrokat fill mass on an altarpiece, La Piedad (1535–1537), in Oñate, northern Spain.[63] Fibers have been reported as strengthening and bulking material in related decorative relief process on paintings, including the halo of St. Jerome in a panel painting attributed to Bartolomé Bermejo.[64]

The thickness of the fill mass varies extending over striated lines and flat areas; in one cross-section, it averages about 60 microns (0.0024 in.); ranging from 90 microns at its thickest to 30 microns at its thinnest (fig. 16). In some areas of applied brocade in the Departure, the tin exhibits slight wrinkling over the fill mass. Though the fill mass was not analyzed on this painting, this suggests that oil was used as the fill mass binder here as well, perhaps with less red lead to accelerate drying. This phenomenon was not noted in the other spalliere paintings, but it may be obscured by restoration.

Between the tin relief’s fill mass and the gesso preparation, there are two layers of material; they are variably thin, combined approximately 10 microns (figs. 16 and 17).[65] The upper layer adjacent to the fill mass exhibits a strong bright white fluorescence under ultraviolet excited visible light and a yellowish tone in normal light. This is interpreted as the adhesive layer used to attach the Pressbrokat to the painting, estimated to be oil or oil-resin. The lower layer adjacent to the gesso ground is composed mostly of white particles with some black particles in an unknown binder. Analysis of this lower layer with SEM-EDS indicates that the white particles appear to be rich in both lead and sulfur; FTIR identified lead sulfate. This lower layer was likely a sealant, used to prevent the oil-based fill mass of the Pressbrokat and its adhesive from being absorbed into the ground layer. A similar layer selectively applied under areas of gilding in the Abduction is thought to seal the absorbent ground from the oil (estimated) components of the mordant (see Betts, French, and Gates, “Painting Technique,” in this volume). A layer such as this is described in the Liber illuministarum: “As a rule, always make sure that the substrate is prepared with or painted in oil colours if a mordant or a ‘varnish’-based or oil-based adhesive is used.”[66]

(left) Cross section of brocade from the Abduction. Top to bottom: visible light, visible light detail, under ultraviolet illumination

Above: Cross section of brocade from the Abduction, SEM-EDS images, acquired at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, showing detail of cross section below, area indicated by red border. Bottom image overlays elemental findings in respective colors

X-radiograph images indicate that the prepared gesso ground was incised both to help position the brocades and to indicate pleats and folds. These incisions are visible in x-radiographs as white lines. The very thin lead-containing material mentioned above, thought to seal the prepared gesso surface, was probably applied after the incisions for placement had been made, and this material seeped into the incised lines, making them x-ray dense in the x-radiograph. The final placement of the brocades and the folds follows the initial incisions closely but not always exactly. (fig. 18) Interestingly, the Reception does not have these white-appearing incisions in the x-radiograph, suggesting that the technique might have evolved during the creation process. On all three panels, further incision lines were made into the brocades once they were applied to the surface to indicate garment folds and pleats. These incision lines generally appear dark in x-radiograph images as material was removed in the process.

Details of Helen’s brocade from the Abduction. Visible light and x-radiograph, with white incision lines from x-radiograph overlaid on visible light image

The identification of drying oil as the main constituent in the Pressbrokat fill mass is especially significant, since the paint used for the three spalliere is proteinaceous egg tempera without detectable additions of drying oil (see Gates et al., “Resolving the Mystery of the Paint Binding Media” in this volume). The adherence to the older practice of using egg tempera for the paint binder while there was copious use of oil in the fill mass of the Pressbrokat supports the theory that artisans with a background in gilding and polychromy, not the painters of these panels, were responsible for the Pressbrokat. In addition to the use of drying oil, very different skill sets were required for the complexities of making tin-relief brocades, likely learned by direct training and practice and probably not shared through treatises. Although oil might have allowed a longer working time, which might have been advantageous in placing these large sheets of Pressbrokat, allowing slight adjustments as necessary, a thick layer of partially cured oil sealed from the air with tin foil might have been problematic; indeed, wrinkling of the tin foil occurred due to the slow drying of the oil. Furthermore, although oil is frequently found as a modifying component of the fill mass in comparative studies, the use of a primarily oil-based Pressbrokat fill mass has been rarely recorded. Wax-based fills, sometimes with additions of oil, resin and pigments, were most frequently used, followed by fills composed of proteinaceous glue with chalk pigments.[67] However, oil was suggested as a possible adhesive in the Liber illuministarum[68] and it may be a component of a related tin-relief ornament, called pasteprints, used on paper in southern Germany.[69] Studies that identified an oil-based fill mass include technical examination of a Swabian sculpture now in the Louvre (a mixture of red lead and calcium carbonate with oil and probably a resin); and of an Ulm School altarpiece, by a follower of Daniel Mauch, divided among three French collections (oil, probably resin, and yellow ochre).[70] In Gipuzkoa in northern Spain, oil was used in the fill mass of several early to mid-sixteenth-century altarpieces, although it was combined with a proteinaceous material.[71]

The use of oil in the Pressbrokat process is also seen in Italian examples. In the above-mentioned 1446 triptych by Vivarini and D’Alemagna in the Accademia, inorganic analysis performed by Stefano Volpin in 1999 identified tin foil over a fill mass composed of lead white and red lead pigments.[74] Although the use of oil could not be corroborated, an independent scholar specializing in the technique claims that oil was indeed the binder.[75] If an oil-based binder was used, it is possible that the high percentage of lead pigments were used here to accelerate the drying process. Drying oil was also found in the fill mass of Pressbrokat on decorative portraits painted by Bonafacio Bembo (active 1447–1478) between 1460 and 1470 for the ceiling of a palace in Cremona, which later became a monastery.[76] In an early sixteenth-century altarpiece in the basilica of Aquileia in Udine province, a mixture of oil, red lead, and gypsum was used as the adhesive for Pressbrokat containing a fill mass of beeswax with chalk.[77] Tin with a fill mass of red lead and oil supported with a paper backing was used in an area of ornamental raised leaves at the base of the same altarpiece.[76] In an early sixteenth-century altarpiece by Giovanni Martini in the Church of San Stefano in Remanzacco, a layer of oil, resin, and red lead was applied to the wood substrate before the application of Pressbrokat containing fill masses of gesso in some cases and wax in others.[77] In this case, an intermediary layer of animal glue was found between the layer containing oil, resin and red lead and the Pressbrokat, complicating the understanding of the purpose of the underlying oil layer. Studies of Italian Pressbrokat on sculpture in Udine by Antonio Tironi and Giovanni Martini found an oil-resin with red lead used as the adhesive for Pressbrokat, with fill masses of either of wax-resin or calcium carbonate. [78]

The technique of Pressbrokat seems to have been forgotten after it fell out of favor in the mid-sixteenth century. As the tin oxidized and darkened, artists probably realized that the effects they had intended would not last. Perhaps the decline of Pressbrokat also can be attributed to slow changes in attitude, inspired in part in the early fifteenth century by Leon Battista Alberti, who in his Della pittura praised artists who could represent gold through paint alone without relying on metal leaf.[79] Pressbrokat’s popularity faded as the tradition of oil painting developed, and with the long drying time for oil, wet-in-wet paint effects were manipulated to illusionistic effect to capture the luminosity of sumptuous brocaded textiles, illustrated in many Early Netherlandish paintings and later Italian paintings, notably those by Venetian artists such as Giovanni Bellini, Titian, and Veronese in the next century.

In summary, the material findings of the Walters’ Pressbrokat supports the localization

of the commission to the Veneto. The methods and materials used in the creation of these works

suggest a collaborative production, with a maker of Pressbrokat brought in to work with the painters. The use of oil in the fill mass, and likely

the adhesive layer, of the Pressbrokat

complements the traditional use of egg tempera in the paintings, and indicates

connection to Northern Italian and Germanic

Pressbrokat executed with drying oil. The use of drying oil combined with

other findings such as the use of large easily incised molds, and possibly

other innovative techniques such as etching used to create the molds, the use

of a yellow transparent glaze instead of gilding as an aesthetic finish, and

the stylistic presentation of the pomegranate design with a forward-facing

calyx may indicate regional influences. The imitation brocades on the Walters

paintings were created with aims of imitating the most expensive textiles of the

time incorporating extra gilded thread to produce the looped metal threads of

bouclé, as well as with red velvet likely produced with expensive Kermes dye. The

finding of few design repeats of brocade throughout the paintings implies the

primary intent of the Pressbrokat

fabrication was the aesthetic texture and not expediency. The

collaborators of Dario di Giovanni working on the Abduction series took on the

challenge of making an immense amount of Pressbrokat

to make a once dazzling presentation, one appropriate for a celebration

as grand and important as the wedding of a queen.

This project has benefited from the generous contributions of many colleagues. We are grateful to Brian Baade, Megan Berkey, Lauren Bradley, David Brickhouse, Milena Dean, Karen French, Rebecca Müller, Jilleen Nadolny, Chris Peterson, Elisabetta Polidori, Ornella Salvadori, and Laszlo Takacs.

[1] For details on the commission, see Spicer, The Abduction of Helen spalliere in this volume.

[2] The authors have chosen to use the term Pressbrokat for the study of these Italian paintings in deference to the common use of this term in Italian scholarship. The first modern study on the topic that included scientific analysis was published in 1963 by Mojmír S. Frinta with supporting analysis by John Mills and Joyce Plesters. Several other studies with analysis of one or several works of art have followed. Of special note are three in-depth studies with accumulated data from a large number of objects, each containing exhaustive bibliographies: Jilleen Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration by Northern European Painters, c. 1200–1500” (PhD thesis, Courtauld Institute, 2001) (a discussion of period terminology for the technique appears in chapter 27 of the dissertation, pp. 343–45); Ainhoa Rodríguez López, “Análisis y classificación de los brocados aplicados de los retablos de Guipúzcoa” (PhD thesis, Uníversidad del país vasco, Facultad de Bellas Artes Departamento de Pintura, Sección de Conservación-Restauración, 2009); and Ingrid Geelen and Delphine Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion: Applied Brocade in the Art of the Low Countries in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (Brussels, 2011). Contributions to the study of Pressbrokat in Italian works have been made by Giuseppina and Teresa Perusini, as well as by Milena Dean and Nicoletta Buttazzoni.

[3] Rosamond E. Mack, “Patterned Silks,” in Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600 (Berkeley, 2002), 27–49 at 31.

[4] Susan Mosher Stuard, Gilding the Market: Luxury and Fashion in Fourteenth-Century Italy (Philadelphia, 2006); and David Jacoby, “Oriental Silks Go West: A Declining Trade in the Later Middle Ages,” in Islamic Artefacts in the Mediterranean World: Trade, Gift, Exchange and Artistic Transfer, ed. Caterina Schmidt Arcangeli and Gerhard Wolf (Venice, 2010), 71–88 at 74.

[5] Jacoby, “Oriental Silks Go West,” 71.

[6] Jacoby, “Oriental Silks Go West,” 73.

[7] Mack, “Patterned Silks,” 45; Lisa Monnas, Merchants, Princes and Painters: Silk Fabrics in Italian and Northern Paintings, 1300–1550 (New Haven, 2008),97

[8] Jacqueline Herald, Renaissance Dress in Italy, 1400–1500 (London, 1981), 78 .

[9] Monnas, Merchants, Princes and Painters, 26, 299–300. Monnas noted that small loops of metal thread massed together locally are called bouclé; when broadly scattered, they are called allucciolato.

[10] The umbrella term for these motifs, the “pomegranate pattern,” is a broad revisionist term, created in the nineteenth century, to describe a variety of stylized natural forms. Herald, Renaissance Dress in Italy, 81; Rosalia Bonito Fanelli, “The Pomegranate Motif in Italian Renaissance Silks: A Semiological Interpretation of Pattern and Color,” in La seta in Europa, sec. XIII–XX, ed. Simonetta Cavacciocchi (Florence, 1993), 507–30 at 507.

[11] Bonito Fanelli, “The Pomegranate Motif in Italian Renaissance Silks,” 514–15.

[12]Jacoby, “Oriental Silks Go West,” 80.

[13] Jacoby, “Oriental Silks Go West,” 81

[14] Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,”333; Rembrandt Duits, Gold Brocade and Renaissance Painting: A Study in Material Culture (London, 2008), 5.

[15] For a thorough discussion of pastiglia techniques, see Ainhoa Rodríguez-López, Narayan Khandekar, Glenn Gates, and Richard Newman, “Materials and Techniques of a Spanish Renaissance Panel Painting,” Studies in Conservation 52, no. 2 (2007): 81–100.

[16] Most of the textiles represented with this technique are brocades, but early examples include lampas silks and unbrocaded velvets.

[17] Ingrid Geelen and Delphine Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion: Applied Brocade in the Art of the Low Countries in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (Brussels, 2011), 131–37; Ainhoa Rodríguez López and Fernando Bazeta Gobantes, “El brocado de estaño en relieve aplicado: Evolución histórica y material en la Europa medieval con atención al arte español (siglos XV-XVI),” Anuario de Estudios Medievales 44, no. 2 (2014): 945–81 at 946.

[18] Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,”186–96 (chap 10: “The Precedents for the Use of Relief in Northern Europe Pre-1200 and the Technical Origins of Tin-relief),” 347–62 (chap 28: “Technical Overview of Tin-Relief”); J.A .Darrah, “White and Golden Tin Foil in Applied Relief Decoration, 1240–1530,” in Looking through Paintings: The Study of Painting Techniques and Materials in Support of Art Historical Research, ed. Erma Hermens(London, 1998),49–79 at 61. For information on the use of tin relief on French sculpture, see Lucretia Kargère and Adriana Rizzo, “Twelfth-Century French Polychrome Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Materials and Techniques” in Metropolitan Museum Studies in Art, Science, and Technlogy 1, pp. 39-72

[19] Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,” Chapter 10, esp. 189.

[20] Lara Broecke, trans., Cennino Cennini’s “Il Libro dell’arte” (London, 2015), chap. 128 (p. 163) and chap. 193 (pp. 222–23). The precise date of the manuscript is unknown, but it is thought to date from the end of the fourteenth century. An English translation of the Liber illuministarum, based on a German translation published by E. Berger in 1912, is included in Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration” (see especially TE18.7, TE 18.9).

[21] Broecke, Cennino Cennini’s “Il Libro dell’arte,” 222.

[22] Cennini recommends stone for casting tin ornaments, but no molds used for relief brocade are known to exist. Mold-making techniques for decorative techniques such as applied brocade likely arose from seal-making techniques, and there are documentary sources for copper and stone molds being used for this purpose. Chalk grounds, which have been suggested as a possible mold material, would have been too brittle and would not have held up to beating the tin in mass production. Jilleen Nadonly, personal conversation, June 8, 2015.

[23] Geelen and Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion, 78, 145.

[24] Nadolny (TE18.7; TE 18.9): this mordant is described in the guild ordinances of Antwerp, 1470

[25] Gilding and toning could be applied before or after placement of Pressbrokat on object. See Geelen, and Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion, 66, 171–72; Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,”353 n. 895. Nadolny notes the imitation of silver colored textiles is more unusual.

[26] Previously noted in Darrah, “White and Golden Tin Foil in Applied Relief Decoration,” 61; Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,”78.

[27] Perusini and Perusini, “La tecnicca del Pressbrokat nell’altare di Giovanni Martini di Remanzacco,” 34.

[28] Mojmír S. Frinta, “The Use of Wax for Appliqué Relief Brocade on Wooden Statuary,” with J.S. Mills and J. Plesters,“Analysis of Wax Appliqué,” Studies in Conservation 8, no. 4 (1963): 136–49 at 143.

[29] Frinta, “The Use of Wax for Appliqué Relief Brocade on Wooden Statuary,” 139 (fig. 3 caption).

[30] Nicoletta Buttazzoni, “Il restauro del polittico di Pellegrino da San Daniele dalla basilica di Aquileia: Nuovi contributi sulla tecnica del Pressbrokat,” in L’arte del legno in Italia: Esperienze e indagini a confronto, ed.Giovan Battista Fidanza (Perugia, 2005), 283–88 at 285

[31]Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,”361; Geelen and Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion, 75; and Buttazzoni, “Il restauro del polittico di Pellegrino da San Daniele dalla basilica di Aquileia,” 286.

[32] Rodríguez López and Bazeta Gobantes, “El brocado de estaño en relieve aplicado,” 975.

[33] Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,” 324. Nadolny includes panels from an altarpiece in Norwich Cathedral, originally from the Church of St. Michael-at-Plea (Norwich), as some of the earliest examples, but the dates of the panels have been contested.

[34]M. Serck-Dewaide, “Relief Decoration on Sculptures and Paintings from the Thirteenth to the Sixteenth Century: Technology and Treatment,” in Cleaning, Retouching and Coatings: Contributions to the 1990 Congress of the International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (London: 1991),36–46 at 37; and M.J. González López, “Brocado aplicado: Fuentes escritas, materiales y técnicas de ejecución,” Boletín del Instituto Andaluz del Patrimonio Histórico 8, No. 30 (2000): 67–77 at 67.

[35] Geelen and Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion, 49–63 (chap. 2: “Migrating Brocades: The Spread of Applied Brocade throughout Europe”); González López, “Brocado aplicado,”67; and Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,” 78.

[36] Geelen and Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion, 49; and Ainhoa Rodríguez López and Fernando Bazeta Gobantes, “El brocado de estaño en relieve aplicado: Evolución histórica y material en la Europa medieval con atención al arte español (siglos XV–XVI),” Annuario de estudios 44, no. 2 (2014): 945–81 at 964.

[37] Giuseppina Perusini and Teresa Perusini, “A problema irrisolto della scultura lignea friulana,” in La scultura lignea nell’arco alpino: Storia, stili e tecniche, ed. Giuseppina Perusini (Udine: Forum, 1999), 203–23 at 206. For Germans artists and artisans working in Venice, see Aikema and Brown, Renaissance Venice and the North, esp. Bernd Roeck, “Venice and Germany: Commercial Contacts and Intellectual Inspirations” (45–55), and Louisa C. Matthew, “Working Abroad: Northern Artists in the Venetian Ambient” (61–69).

[38] Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,” 328.

[39] John Payne, “Exploring a Fifteenth-Century Garden: A Restoration Uncovers the Past,” Art Bulletin of Victoria 35 (1994): 7–19 at 10. Archival photos from 1934 show earlier states of condition and residues of the original brocade in x-radiograph details.

[40] Documentation supplied by Bernadett Tóth was gathered as part of her MA thesis in art history submitted at the Eötvös Loránd University of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary, in 2009. Images of the Pressbrokat show similar sketchy lines and curving “c” lines.

[41] Giovanna Nepi Scirè, “Prelude,” in Renaissance Venice and the North: Crosscurrents in the Time of Durer, Bellini, and Titian, ed. Bernard Aikema and Beverly Louise Brown (London, 2000), 172–75 at 172. Chemical and cross-sectional investigation report generated by Dr. Stefano Volpin: Indagini microchimiche e Stratigrafiche su Campioni di Pellicola, Trittico raffigurante Madonna in trono tra i Santi Gregorio, Girolamo, Ambrogio e Agostino, Antonio Vivarini e Giovanni D’Alemagna, Cat. 625, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice. February 1999. Cross sections indicate that Pressbrokat was used in the baldachin, in the Madonna’s gown, and in St. Augustine’s robe

[42] Personal communication with Rebecca Müller, Kunstgeschichtliches Institut, Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main, May–June 2018: works with suspected, but unconfirmed, areas of Pressbrokat include The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1440–1445 (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) (in the sleeve of the figure in blue at far left) and the painted rear façade of the Madonna del Rosario polyptych, 1443, Capella di San Tarasio, Chiesa di San Zaccaria, Venice (in very small details such as collars). In the same church it is used on a chest that stands on the rear side of the main altarpiece with the relics of St. Zacharias.

[43] Personal communication with Rebecca Müller, Kunstgeschichtliches Institut, Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main, May 30, 2018; personal communication between Italian painting conservator Milena Dean and Walters Senior Painting Conservator Karen French, September 5, 2016. The textured collar and sleeve on Pisanello’s Portrait of Leonello d’Este, 1441, on panel, in the Accademia Carrara, Bergamo, was also created with techniques other than Pressbrokat. Personal communication with Giovanni Valagussa, Conservatore dell’Accademia Carrara, April 1, 2016. Pisanello’s (unfinished)Tournament Scene fresco in the Sala del Pisanello in the Ducal Palace, Mantua (from 1433) incorporates relief; it is reportedly created with pastiglia covered with metal foil.

[44] Geelen and Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion, 57.

[45] The workshop included Antonio Tironi, Giovanni Martini, and sculptor Bartolomeo dall’Occhio. Interestingly, Giovanni Martini (ca. 1470–1535) may have had a connection with the Vivarini workshop, known to have used Pressbrokat, as it is argued that he studied in Venice with Alvise Vivarini (1442/53–1503/05) , son of Antonio Vivarini, early in his career.

[46] For information on dagging, see John Block Friedman, “The Iconography of Dagged Clothing and Its Reception by Moralist Writers,” Medieval Clothing and Textiles 9 (2013): 121–38 at 133.

[47] Based on a corrosion rate of 0.013 inches per 1,000 years; see H.H. Uhlig, Corrosion and Corrosion Control, 2nd ed. (New York, 1971), 165–66. Given that the density of tin metal is 7.3g/cc, and that of tin oxide are so similar, specifically 7.1g/cc as the mineral cassiterite, then the thickness of the completely mineralized tin oxide layer in the Pressbrokat sample suggests that the original tin metal thickness was approximately as thick, around 30 microns. Using a minimum corrosion rate for tin as 0.33 micron per year, as reported by Uhlig for lead metal, and assuming a similar corrosion rate for tin metal based on the similar chemistries of lead and tin, then the complete corrosion of the original tin metal used for the Pressbrokat occurred within about 90 years, as a first approximation.

[48] Restoration is most extensive on the Reception and least on the Departure. Metallic paint was probably applied in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. Brass paint on the gold textiles was identified with x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy; the paint on the silver textiles may be aluminum-based, but it has not darkened significantly and was not analyzed.

[49] For gilding, see Geelen and Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion, 165. For vermeil, see Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,” 360–61 (and appendix).

[50] Geelen and Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion, chap. 3. and 78.

[51] Perusini and Perusini, “A problema irrisolto della scultura lignea friulana,” 206.

[52] Large sheets of Pressbrokat (33 × 17 cm) were found on the Rokycany and Rokovnik altars in Prague (see Štěpánka Chlumská and Radka Šefců, “The Tin-Relief Technique on the Panel Paintings of the Rakovnik, Rokycany and Litoměřice Altars,” Technologia Artis 6 [2008]: 66–97 at 73), In addition, a panel measuring 33.2 by 16.4 centimeters was used in Friedrich Herlin’s 1466 altarpiece in the Church of St James, Rothenburg. See K.-W. Bachmann, E. Oellermann, and J. Taubert, “The Conservation and Technique of the Herlin Altarpiece (1466),” Studies in Conservation 15, no. 4 (1970): 327–69, 355.

[53] Several factors limit the absolute qualification of this statement including areas of damage to the tin and materials associated with the auxiliary support attached to the original panels that impede or obscure the designs in x-radiograph images. See French and Gordon, “Conservation,” in this volume.

[54] Jill Nadolny, personal communication with the author, June 8, 2015.

[55] Geelen and Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion, 148.

[56] Geelen and Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion, 147.

[57] Milena Dean and Gianluca Poldi, Madonna col Bambino, in Il paradiso riconquistato: Trame d’oro e colore nella pittura di Michele Giambono, ed. Matteo Ceriana and Valeria Poletto (Venice, 2016), 173–77 at 174, 176

[58] Chemical and cross-sectional investigation report generated by Stefano Volpin, Antonella Casoli, Elisa Campani, and Michela Berzioli, Indagini Microchimiche e Stratigrafiche del Colore, Antonio Falier da Negroponte, Madonna con Bambino in Trono Pala d’altare conservata nella Chiesa di San Francesco della Vigna a Venezia, indagini scientifich per l’arte e il restauro (Padua, 2008), 12,

[59] Geelen and Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion, 78 (their study found the average to be 10–22 threads per centimeter). The “threads per centimeter” measurement on the Walters brocades (especially in the Departure) falls in the upper range.

[60] Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,”79.

[61] Buttazzoni, “Il restauro del polittico di Pellegrino da San Daniele dalla basilica di Aquileia,” 286.

[62] Perusini and Perusini, “La tecnica del ‘Pressbrokat’ nell’altare di Giovanni Martini di Remanzacco,” 35

[63] Ainhoa Rodríguez et al., “Characterization of Calcium Sulfate Grounds and Fillings of Applied Tin-Relief Brocades by Raman Spectroscopy, Fourier Transform infrared Spectroscopy, and Scanning Electron Microscopy,” Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 41, no. 11 (2010): 1517–24 at 1521.

[64] See Rodríguez-López, Khandekar, Gates, and Newman, “Materials and Techniques of a Spanish Renaissance Panel Painting.”

[65] It was not possible to gather enough material from this thinly applied double layer for organic analysis.

[66] Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,”App. 1, Section 18 [TE 18.9, p. 463] (based on a published transcription of the Liber illuministarum by E. Berger in 1912). In associated note 273 Nadolny explains that the use of ‘mordant’ here is implying an oil-bound mixture containing lead pigments.

[67] Geelen and Steyaert, Imitation and Illusion, 152 ,155; Nadolnly, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,” 347–62 (chap 28: “Technical Overview of Tin-Relief”).

[68] Nadolny, “The Techniques and Use of Gilded Relief Decoration,”App. 1, Section 18 [TE] (based on a published transcription of the Liber illuministarum by E. Berger in 1912), 463 n. 273.

[69] Elizabeth Coombs, Eugene Farrell, and Richard S. Field, Pasteprints: A Technical and Art Historical Investigation (Cambridge, Mass: Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard University Art Museums, 1986).

[70] Sylvie Colinart and Myriam Eveno, “La polychromie: Les études de laboratoire,” in Sculptures médiévales allemandes: Conservation et restauration, ed. Sophie Guillot de Suduiraut (Paris, 1993), 157–75.

[71] Ainhoa Rodríguez-López and Fernando Bazeta Gobantes,“Classification of the Typologies, Techniques and Materials of the Applied Brocades of the Altarpieces of Gipuzkoa by Means of the Analytical Techniques of Laboratory,” Ninth International Conference on Non-Destructive Testing of Art, Jerusalem, May 25–30, 2008, 1–10 at 6–7.

[72] Chemical and cross-sectional investigation report generated by Dr. Stefano Volpin: Indagini microchimiche e stratigrafiche su Campioni di Pellicola, Trittico raffigurante Madonna in trono tra i Santi Gregorio, Girolamo, Ambrogio e Agostino, Antonio Vivarini e Giovanni D’Alemagna.

[73] Personal communication from Italian conservator Milena Dean to Walters Senior Paintings Conservator Karen French, September 5, 2016.

[74] The paintings have been dispersed into several collections. The analysis with FTIR-ATR of two samples from portraits in a Geneva collection revealed the presence of oxidized oil-fill mass that was possibly pigmented under tin foil. See Léa Guillaume-Gentil, “Bonifacio Bembo (1420–1477) et les closoirs du monastère de La Colombe : Étude stylistique et matérielle d’un cycle de peintures décoratives,” Mémoire de maitrise, 2012, Haute École des Arts de Berne, p. 62

[75] Buttazzoni, “Il restauro del polittico di Pellegrino da San Daniele dalla basilica di Aquileia,” 285.

[76] Buttazzoni, “Il restauro del polittico di Pellegrino da San Daniele dalla basilica di Aquileia,” 285.

[77] Perusini and Perusini, “La tecnica del ‘Pressbrokat nell’altare de Giovanni Marini di Remanzacco,” 35.

[78] Giuseppina Perusini and Milena Dean, “La tecniche esecutive della Madonna in trono col Bambino di Alverà (circa 1450),” in Scultura lignea: Tecniche esecutive, conservazione e restauro, ed. Anna Maria Spiazzi and Luca Majoli (Milan, 2007), 117–27 at 124–25.

[79] Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting, ed. and trans. John Richard Spencer, rev. ed. (New Haven, 1966), 64.