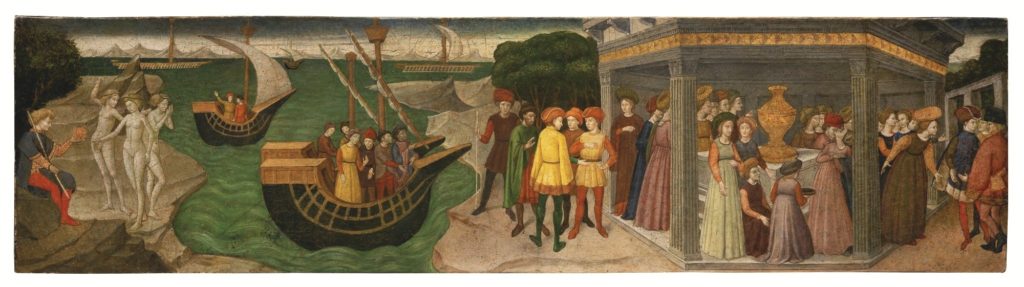

The series of three very large panel paintings in the Walters Art Museum that are the focus of this essay depicts the abduction of Helen, queen of Sparta by the Trojan prince Paris: The Departure of Queen Helen and Her Entourage for Cythera, The Abduction of Helen from Cythera, and The Reception of Helen at Troy (fig. 1). They are here attributed to the Paduan-trained painter Dario di Giovanni and collaborators as part of an extraordinary, larger commission of five or six paintings carried out in Venice around 1468–1469 in celebration of the proxy marriage of the young Caterina Corner (1455/56–1520) with Jacques II Lusignan, king of Cyprus, in July 1468.[1] No document specifically referencing the commission has been identified; however, the multiple components of this proposal are sufficiently intertwined for a working hypothesis about the painter, the subject, and the occasion for the commission. The paintings are remarkable for their qualities as history paintings (istorie [plural] in contemporary usage), including technical features that surely dazzled contemporary viewers, and for the perspectives they offer on significant gaps in current knowledge of Venetian domestic painting in the 1400s.[2]

This new characterization of the series constitutes a major change: the paintings were previously assigned to various artists over time but principally to the “Master of the Stories of Helen,” in the Venetian circle of the Vivarini family, with datings ranging from 1445–50 to the later 1460s, the latter finding more adherents.[3] There has been no specific proposal as to their function, which, given their size, is a primary consideration. However, the Walters paintings have rarely been on public view, residing in the museum’s storage for decades and for several years in conservation.

The paucity of extant secular panel painting in Italy outside of Tuscany for this period means that there are not many works with which to compare them. Building an argument for a new reading of the Abduction of Helen series calls for a new approach, beginning with a basic description of the series’ essential features.

Constructing an Initial Frame of Reference

The Abduction of Helen series comprises three immense Italian fifteenth-century panel paintings with a total width unframed of 306 inches (778 cm, originally slightly wider), painted in tempera on spruce panels with applied Pressbrokat detailing, representing a subject taken from ancient history: the abduction of Helen, queen of Sparta, by the Trojan prince Paris. They were acquired by Henry Walters after 1905, when they were auctioned in a sale in Rome, and before 1915, when they are referenced in an article by art historian Bernard Berenson as being in Walters’ collection.[4] Two other extant paintings were certainly part of the same overarching commission (and possibly a third).

The Walters panels are spalliere, paintings generally installed at shoulder height (spalla = shoulder) or higher, depending on the height of the actual painting and of the ceiling), set into woodwork or molding, sometimes suggesting the conceit of an open window through which history appears to come alive.[5] The development of this type of panel painting is associated with Florence in the second half of the 1400s, and the only earlier or larger known monumental spalliera series is Paolo Uccello’s three-part Battle of San Romano, ca. 1438–1440 (fig. 2), with a combined width of 377 inches (957 cm).[6]

Paolo Uccello (1397–1475), The Battle of San Romano, ca. 1438–1440. Tempera on poplar. Left: National Gallery, London, NG 583, 71.6 × 126 in. (182 × 320 cm); center: Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence, 1890 no. 479, 71.6 × 126 in. (182 × 320 cm); right: Musée du Louvre, Paris, MI 479, 71.6 × 125 in. (182 × 317 cm). London: © The National Gallery, London; Florence: Scala / Art Resource; Paris: © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

The earliest provenance documentation (see Coda) places the Walters series in England in the 1800s, at which time the three panels were together with two other panels, a Garden of Love and a Garden Wall with a Trellis of Roses (figs. 3, 4). If five fifteenth-century paintings, inter-related by artist, theme, and physical characteristics, were together in the 1800s, it is a reasonable assumption that they were from the same commission and, given the combination, celebrated love and marriage.

Master of the Stories of Helen, Studio of Antonio Vivarini (attributed here to Dario di Giovanni and collaborators), The Garden of Love. 60 1/16 × 94 1/16 in. (152.5 × 239 cm). National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton bequest, 1948, acc. no. 1827/4

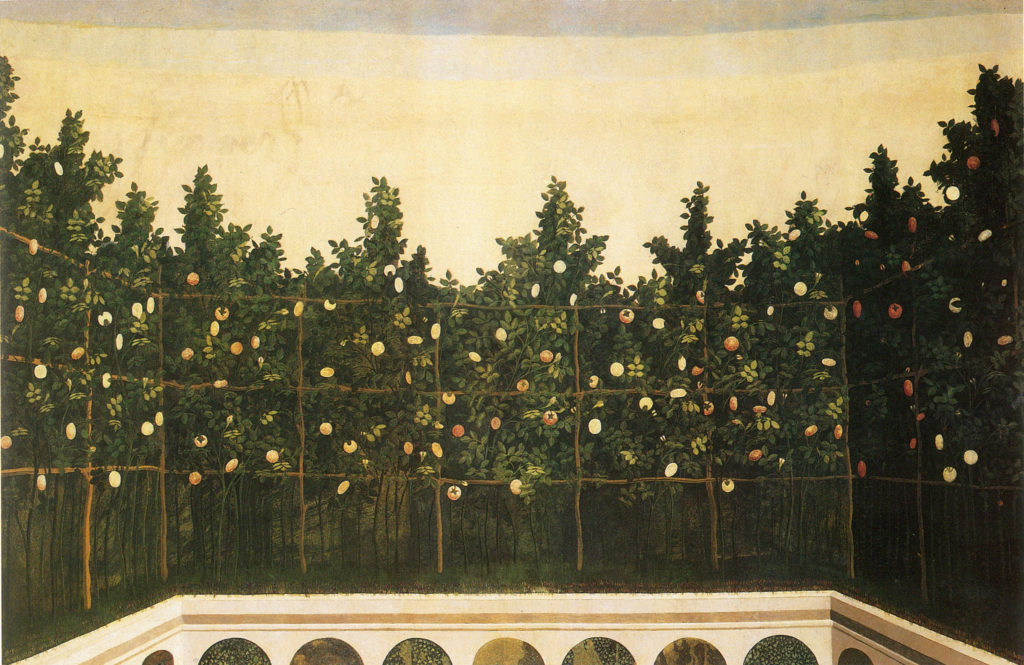

Collaborator of Dario di Giovanni (from the Vivarini family workshop?), Garden Wall with a Trellis of Roses, ca. 1468. Tempera on spruce, 60 × 92 in. (152.5 × 233.5 cm). Private collection, Venice

Three factors affect a discussion of geographical origins. The geographical indicators point to the Veneto, which would be consistent with the traditional attribution to a Venetian artist working in the circle of the Vivarini family workshop in the 1460s or possibly earlier. Any attempt to place the panels at a distance from the Veneto bears an extra burden of proof. First, spruce, in place of the traditional poplar, does not appear to have been used as a support in Italy outside of the Veneto or Lombardy.[7] Second, the extensive presence of Pressbrokat, a special technique for simulating the richest brocades with glittering surfaces of gold and silver threads (for which see Betts and Gates, “Dressed in Tin,” in this volume), is truly extraordinary, especially for a secular history painting, in which context it appears to be otherwise undocumented. It would most certainly convey magnificence. While Pressbrokat is widely encountered in Northern Europe, its use in Italy outside of the Veneto and Friuli is also undocumented. The only extant, traditional usage in Venice is the 1446 Altarpiece with Madonna and Child with Saints (Galleria della Academia, Venice), of which the lead painter was Giovani d’Alemagna (from Ulm), whom Dario knew in Padua. Third, the adaptation of a type of Roman altar characteristic of the region around Padua has been identified otherwise only in the work of other artists active in the region, including Giovanni d’Alemagna.

Five large paintings on inter-related secular subjects for domestic spaces within the same palace constituted a very sizable commission for a private patron or artist in the 1400s. The subject matter indicates a wedding, while the attention to magnificence expressed through clothing points to one of significance, within the highest rungs of society.[8] Although an important wedding normally enlarged a family’s sense of identity, there is no obvious reference to a family, even a family device: just a single initial (“C”) on the queen’s pennant in the first painting. As this is a striking, large-scale representation of ancient history, and Trojan history at that, for a domestic space, what families in the region were most likely to have embraced this form of self-representation?

Were there wealthy, elite (probably noble) families of the Veneto who celebrated major marriages during this period, marriages for which an extraordinary level of magnificence framed through allusions to ancient history was appropriate? My research yielded only one marriage and family consistent with the cited properties and their implications: the extended Corner (written “Cornaro” in the rest of Italy), family, one of the oldest and wealthiest noble families of Venice, with palaces dotting the city and a wedding to celebrate in 1468, the consequences of which would reverberate throughout the Venetian Republic.

History Paintings for the Private Sphere in Venice

For all the glories of large-scale narrative painting for public spaces in Venice during the 1400s that Patricia Fortini Brown and many others have extensively documented, very little has been established regarding this category of domestic painting from the 1400s in Venice.[9] Perhaps one reason for the mysterious absence of evidence for domestic secular wall painting in Venice (versus, for example, Florence and the Venetian mainland) might be that many were probably executed in fresco, a medium popular and long lasting for domestic decoration on the Venetian mainland but gradually destroyed by damp in the atmosphere of the lagoon.[10] Wall decoration might also involve various kinds of hangings including Flemish tapestries, often millefleurs (a pattern of scattered flowers), mentioned in existing inventories.[11] With their rich textures and gold and silver threads, they contributed to an atmosphere of luxurious décor valued by the Venetian elite, but these also disintegrate in damp conditions. Indeed, the defining physical impact of the Walters spalliere—their size and the effect throughout of simulated rich brocades, complete with the illusion of gold and silver threads (due to the Pressbrokat)—might indicate that the series was conceived in part to compete with or replace more expensive but fading Flemish tapestries that did not lend themselves to shaping an iconographic program, especially as there was as yet no Italian center for tapestry production.

The current state of knowledge of fifteenth-century commissions for large-scale history painting for the domestic sphere in Venice could be described as a vacuum with bookends, both of the latter, as it happens, supplied by members of the Corner family. The earliest evidence for istorie in a domestic palace in Venice of which I am aware is from 1437.[12] In that year Giovanni d’Alemagna (1399–1450) was commissioned to paint for a chapel in the palace of Pietro Donato, the bishop in Padua, a series of istorie with a border of simulated porphyry and serpentine as he had done “in la casa de messer zuan Corner a Vinexia,” thus, “in the palace in Venice of the Sen. Giovanni Corner,” the Venetian magistrate or podestà of Padua (born 1374), most likely for the family palace in Venice acquired by his father, Cav. Federico Corner, and uncles in 1364.[13] This palace, now known as Ca’ Loredan for the family to whom it passed, was the one where in 1366 the Corners hosted Peter I Lusignan, king of Cyprus, with consequences for the founding of the branch of the family (known as Piscopia [for their estates in Cyprus]) that would dominate the sugar trade between Venice and Cyprus.

The next previously identified large-scale history paintings that are probably for a Venetian palace were created by Vittore Carpaccio in the last years of the century. They include The Story of Alcyone (Philadelphia Museum of Art), though no location or patron has been proposed.[14] It is not until 1505 that we have a documented commission of surviving paintings: four canvases (of which two were delivered) for Francesco Corner (a nephew of Caterina Corner) contracted with Andrea Mantegna and after his death, partially carried out by Giovanni Bellini (fig. 5). They address the virtues of the Corner family’s Roman ancestors of the Cornelia line (including most famously the general P. Cornelius Scipio Africanus) for a camerino (small chamber) in a family palace.[15] Two examples do not demonstrate a long-term pattern of commissions, but, in the absence of evidence of commissions by other families, they suggest receptivity toward a role for art in self-representation.

Giovanni Bellini (1431/36–1516), The Continence of Publius Cornelius Scipio, Known as Africanus, after 1506. Oil on canvas, 29 7/16 × 140 1/4 in. (74.8 × 356.2 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Samuel H. Kress Collection, 152.2.7

Where would spalliere such as the Walters’ have been displayed? In late medieval and Renaissance palaces in Venice, the layout was quite standardized, so that even though floor plans of Corner palaces from the 1400s have not survived, certain assumptions are justified.[16] The portego, the large gallery running from front to back on the main living floor, might be hung with tapestries or, at least by the 1500s, with paintings. This was an essentially public space off which opened private chambers where important visitors would be entertained. The Walters series could have been installed in one of the latter.[17] The two large companion paintings making up a garden of lovers (see fig. 3 and 4), part of the same commission, would have been for a separate chamber, a more intimate camerino, where, given the angle of vision, they might have been installed closer to eye level so that persons entering the space would feel delightfully surrounded by nature and affection.[18]

Venice and the Corner Family

For the last half of the 1400s the Republic of Venice, centered in the city perched on islands in the midst of the lagoon, as represented by Erhard Reuwich in 1486 (fig. 6), was at the height of its prosperity and influence on the international stage as a great maritime power (fig. 7).[19] Its stato da màr (maritime possessions) stretched along the eastern coast of the Adriatic from Istria to Dalmatia, Albania, ports in the Peloponnese, Cythera, the Greek archipelagoes, and Crete, reaching its eastward apogee with the acquisition of Cyprus in 1489, all steps on the spice and luxury goods routes to Alexandria, Antioch, and Constantinople. In the first half of the century, Venice expanded and deepened its control of cities on the mainland, its terrafirma, including in 1406 the university city of Padua. The fame of Venice owed much to its projection of magnificence, which in turn owed a great deal to the palaces of its nobility, among which were three belonging to the extended Corner family that are relevant to this essay: the casa (“house”; Venetians used “palazzo” only for the doge’s palace) known as Ca’Corner at San Cassiano, which is where Caterina grew up, where the Walters Abduction series most likely hung (fig. 8, with 18th-century facade), and which was later known as Ca’Corner della Regina (“of the queen”), referencing its use by Caterina after her abdication;[20] Ca’ Corner (Loredan, the family to whom it passed); and Ca’ Corner della Ca’ Granda, celebrated by 1500 as the palace of the “magnificent knight Zorzi (Giorgio) Corner, brother of the queen of Cyprus.”[21]

Erhard Reuwich (ca. 1455–1490), Panorama of Venice, foldout page from Bernhard van Breydenbach, Peregrinatio in Terra Sanctam (Mainz, 1486). Woodcut. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, bequest of Henry Walters, 1931, acc. no. 91.283

The Venetian Maritime Dominions in 1489

Ca’ Corner della Regina, façade (18th century) facing the Grand Canal, Venice

Nevertheless, conditions were changing that already by the turn of the century would reduce the republic’s prosperity and power, underlining the importance of controlling Cyprus. The first, in 1453, was the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire. Although trading relations with Mamluk Egypt had long been to mutual benefit, the growing territorial ambitions of the Ottomans and the Venetian defeat in the Battle of Zonchio in 1499 were a shock. The year before, the Portuguese arrived in Calicut, having round the Cape of Good Hope, becoming the first Europeans to reach the spice markets of Asia by sea, opening new trade routes for these profitable commodities that bypassed Venice.

The Corner, like much of the Venetian nobility, were merchants, and therefore vulnerable to such shifts. However, many of them rose to high office in the government of the republic and in the Catholic Church.[22] Another aspect of their dignity in the eyes of Venetians was their antiquity, not only in their involvement in the affairs of Venice back at least to the seventh century, but in their accepted claims of Roman ancestry as descendants of the gens Cornelia. This claim was to become an element in the pedigree of young Caterina as queen, expressed, for example, by the poet Bartolomeo Pagello in his poem on the wedding “De nuptiis Zachi Cypriorum regi et Catherinae Corneliae ex sanguine Venetorum,” (On the nuptials of Jacques, king of the Cypriots, and Catherine Cornelia of the blood of the Venetians”) written between 1468 and 1473.[23]

There is little documented or to be surmised about Caterina prior to the discussions surrounding the marriage.[24] Born in 1455 or 1456, she apparently received the convent education (in Padua) of a young girl of her class, with little else to distinguish her. Everything changed when the proposal was put to Jacques II Lusignan of Cyprus that marrying her might be a more attractive option than other family alliances in the region might offer. While the Corner family line could not claim royal blood, Caterina could, through her mother, Fiorenza Crispo, a niece of the emperor of Trebizond. More to the point, the king owed tens of thousands of ducats to Marco Corner. The astonishing dowry of 100,000 ducats he offered (versus the official limit of 1,600 ducats) would more than eliminate the king’s debt.[25] The island of Cyprus needed protection, which Venice could offer. For Marco Corner and his family, the prestige and social value of having performed such a level of service to the state was incalculable; indeed, members of the Venetian Senate were apparently already thinking about how to shape such a marriage alliance into an opportunity to gain control of Cyprus, the last remaining stepping-stone to eastern Mediterranean markets that Venice did not already control.[26]

In connection with the negotiations, a portrait of Caterina as a prospective bride, to be sent to Jacques for his approval, was said by her earliest biographer, Antonio Colbertaldo (1556–1602), to have been commissioned from “Dario da Treviso” (Dario di Giovanni, ca. 1420–before 1498).[27] There is no reason to doubt this statement, as it is impossible to imagine a young king at this period not insisting on a portrait, whether or not one is cited in surviving documents of the negotiations.[28] Though Dario was associated with numerous noble patrons and major projects (few of which survive), he was hardly so well known as someone like Jacopo Bellini, whose name Colbertaldo could have inserted if it was a question of inflating the portrait’s prestige after the fact.[29] In any case, Dario’s skills at rendering a nuanced profile of a young woman are demonstrated in the Walters Departure (fig. 9) and in his two extant donor portraits. In republics such as Venice or Florence, elite families normally sought allegiances (and brides) locally, so there was no tradition of such portraits in either city.[30] It was, however, a common practice for European rulers in the 1400s in connection with long-distance searches for a bride.[31] Examples abound. King Charles VI of France (ca. 1380–1422) sent a painter to three royal courts before marrying Isabeau of Bavaria (1371–1435).[32] In 1442, Henry VI of England commissioned portraits of the daughters of the count of Armagnac depicting “their beaulte and color skynne and their countenaunces, with al maner of features.”[33] In Italy, for example, the Sforza court portraitist in Milan, Bugatto Zanetto (ca. 1433–1476), was called upon at least twice to produce portraits of prospective brides.[34] According to a diplomatic report, Jacques had previously been shown the portrait of the niece of Pope Pius II in connection with a potential deal (which Jacques declined) that the pope would crown him (giving him legitimacy) if he married her.[35] The portrait of Caterina is presumed lost, but it prompts the question: What did Caterina look like?

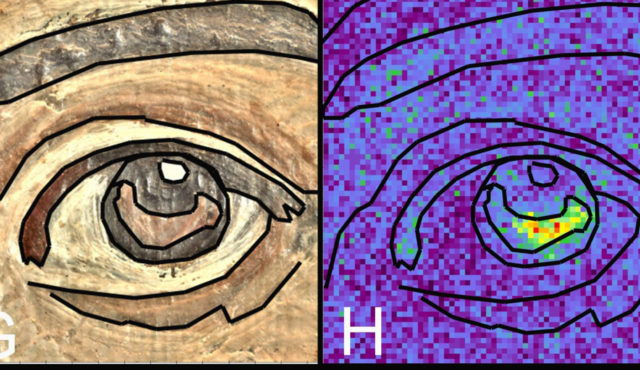

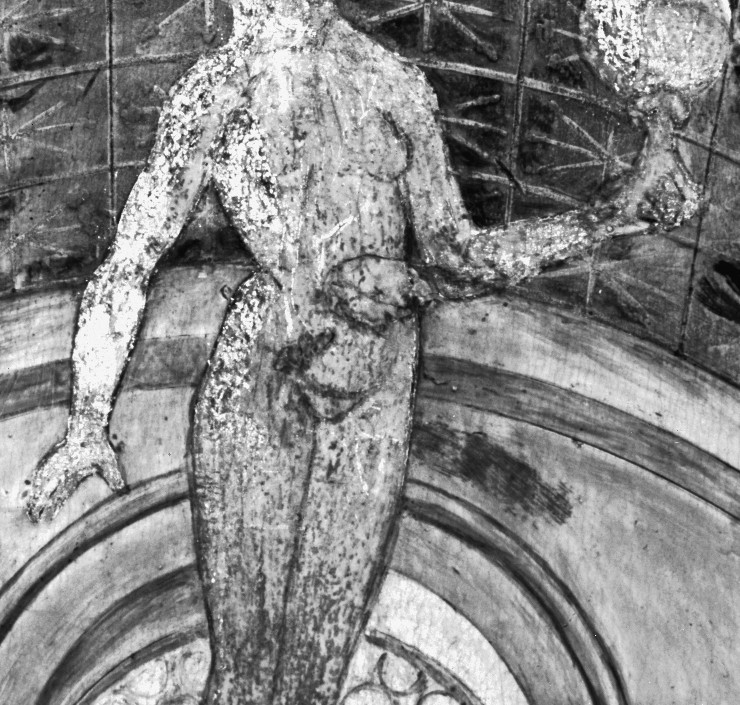

Detail from the Abduction

Again according to Colbertaldo, Caterina was “a young girl of about age fourteen whose face resembled the clear sky, the cheeks had no reason to envy vermilion roses, lips in the likeness of coral with teeth like little pearls, milk-white breasts, black eyelashes, eyes shining like two burning stars, and golden hair.”[36] Perhaps Caterina did look like that, but in any case, irresistible beauty that could arouse desire was called for in a royal bride, and what constituted irresistible beauty was codified in literature and the visual arts during the period. Colbertaldo’s description is conventional and nearly identical to those of so many historic paragons of female beauty, including those by the fourteenth-century humanist Francesco Petrarch of his beloved Laura, which were ingrained in the contemporary elite imagination.[37]

The unresolved question of Caterina’s appearance brings to the fore a sixth painting (fig. 10), tied to the others by manner, support, and use of Pressbrokat but not by provenance: a young girl, her blond hair tied up casually and wearing the same cut of dress as the older of the two girls in the Walters Departure, playing with a unicorn, a traditional symbol of chastity or virginity. In this context it could well be an allegory of “Caterina Corner as Chastity.”[38] There is a generic similarity of the face and that of Helen, but it is most unlikely that this is the “prospective bride” portrait, which would be a close-up depiction. It may be an earlier gift for a family member or tutor.

Dario di Giovanni, Caterina Corner as Chastity, ca. 1467–68. Tempera and Pressbrokat on spruce, 39.4 × 35.4 in. (100 × 90 cm). Keresztény Múzeum, Esztrogom, no. 13-18, 55.212. Photograph Mudrák Attila

Apparently, the portrait did its work. On July 31, 1468, Caterina was married in Venice to Jacques II of Cyprus, represented by his proxy, the Cypriot ambassador Philippe Mistachiel. The wedding was treated as a major civic event, enacted with all the fanfare for which Venice was so famous; and the ceremony took place not in the Corner palace but in the great ritual spaces of the ducal palace, with Doge Cristoforo Moro acting in place of Caterina’s father, Marco.[39]

Thus began Caterina’s metamorphosis from Caterina Corner, daughter of Marco Corner, not only to queen of Cyprus (which she became instantly, even though she would not join her husband in Cyprus for four years) but to “daughter of Venice,” an appellation with legal connotations that would deeply affect her life.[40] As the historian and poet Pietro Bembo put it, “It was from the Senate that he [Jacques Lusignan] had taken Cornelia [of the Cornelian line] to wife, taken on, as it were, as a daughter of the Republic (reipublicae filiam) guaranteed by the state.”[41] Similarly, the attendance of “Serenissima Domina Catherina Cornelia Veneta Regina Cypri” (the Most Serene Lady Caterina Cornelia Veneta, Queen of Cyprus” was noted at a state event in 1469.[42] Much the same wording was used by the poet Bartolomeo Pagello in a poem written between the years 1468 and 1473 celebrating the wedding.[43]

In quick succession after her happy reception in Cyprus in 1472, Caterina became pregnant; her husband the king died of a stomach ailment under somewhat suspicious circumstances, causing Caterina to become regent for her unborn child; and her son was born but died before his first year. Caterina now ruled as queen in her own right, a momentous expansion of responsibilities, but with the political and sometimes military support of her parent, Venice.[44] In the following years, pressure would grow on Caterina to abdicate in favor of this parent, and at last in 1489, under pressure from her brother Giorgio (subsequently knighted for his efforts), she acceded.

Her return to Venice and the act of handing over her crown to the doge were treated with the utmost ceremony, giving every public sign of the republic’s gratitude for her personal sacrifice and statesmanship, qualities they were not accustomed to acknowledging in a woman.[45] Of course the senate was overjoyed to have at last acquired Cyprus, and without firing a shot. On the basis of this act, the fortunes of her brother Giorgio soared, and Caterina retired to a fiefdom created for her by the republic on the terrafirma at Asolo, where she patronized poets and humanists as a manifestation of royal status while staying away from politics, with the exception of tireless efforts, primarily behind the scenes, to secure her family’s fortunes and continue support for Cyprus.[46] Portraits of Caterina by Gentile Bellini from around 1500, as that in Budapest (fig. 11), show her crowned but introspective.[47] Following the death of the “daughter of Venice” in 1510, the family’s claim on her as a Corner could at last take hold, generating a multitude of sculpture, portraits, and large-scale paintings on canvas celebrating her, but most especially re-creating her triumphal return to Venice and the gift of her crown.[48]

Gentile Bellini (ca. 1429–1507), Portrait of Queen Caterina, ca. 1500. Oil on poplar, 24.8 × 19.2 in. (63 × 49 cm). Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest. © The Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest / Scala / Art Resource, NY

The Painter

Dario di Giovanni, Caterina’s portraitist and proposed as painter of the Walters Abduction of Helen series, is something of an enigma. While there are many documents noting his responsibility for major projects on behalf of noble families or institutions, almost none of these paintings survive. On the other hand, the major surviving projects associated with him are not documented. The result is that past efforts to construct a body of work for Dario and/or the “Master of the Story of Helen” have depended on stylistic analysis. That this is not unusual for a period when few paintings were signed does not make the task easier.

The known attribution history of the paintings begins in 1905, when the paintings appeared at public auction in Rome with attributions to Vittore Carpaccio and to a “pedestrian imitator of Piero della Francesca.”[49] In 1915, by which time the paintings had been acquired by Henry Walters, Bernard Berenson established a fruitful framework by proposing that the artist was from the workshop or circle of Antonio Vivarini (ca. 1415–ca.1480, active in Venice and Padua).[50] Indeed both individual artists and altarpieces from the famous workshop, known for a lavish courtly style with elaborate clothing applied to exclusively religious subjects, exemplified by the Altarpiece of Santa Sabina of 1443 (fig. 12, detail) and the Adoration of the Three Kings, ca. 1445/47 (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin,), have since proved to be important for understanding the Walters paintings. In 1962 this attribution was refined to “The Master of the Story of Helen,” within the Vivarini circle.[51] This appellation was generally retained, including by Federico Zeri in his 1976 Italian Paintings in the Walters Art Gallery, adding the critical insight that the artist had adapted Roman altars characteristic of Padua, a motif shared with Giovanni d’Alemagna, Antonio Vivarini’s partner.[52]

Antonio Vivarini (ca. 1415–1476/84) and Giovanni d’Alemagna (1399-1450), Santa Sabina Altarpiece, 1443: detail of lower register. Tempera and gold leaf on wood. Church of San Zaccaria, Venice

Zeri rejected, without comment, the attribution proposed by Luigi Coletti, in a footnote to his Pittura Veneta del Quattrocento (1953), to the Paduan-trained Dario di Giovanni (Dario da Pordenone, ca. 1419/1420–before 1498), previously little studied outside of regional histories.[53] Coletti associated Dario with the Melbourne painting (see fig. 3), a signed Madonna of Mercy (Museo civico, Bassano), the chapel of St. Nicholas in the cathedral of Pordenone (see figs. 18, 30), and frescos (facades or wall paintings) in Asolo (see fig. 15), Treviso, Serravalle, and Conigliano, drawing in part on extensive archival research on the artist published already in 1910.[54] Coletti’s attribution was supported by Italo Furlan, whose 1968 article Zeri does not cite, through illustrating convincing stylistic comparisons between the Pordenone frescos and the Abduction series.[55] Zeri’s rejection was followed by Miklós Boskovits (1977) and Giorgio Fossaluzza (2003), again without comment.[56] Recently (2019) Stephen Campbell has underlined the porosity of the artistic environment in Venice, with evident movement of artists between Tuscany and Padua/Venice, and sites in the Marches, as an important element in the interpretation of the Walters panels, a perspective fundamental as well to the following discussion.[57]

As in many large Renaissance paintings, there may be multiple hands responsible for what we see—in this case, independent collaborators as well as assistants. There is the craftsman responsible for the Pressbrokat, a distinct skill that appears not to have been practiced in Venice for some years, so that it is likely that he was invited to Venice for the purpose, possibly from the northern reaches of the Veneto, such as Udine, where the technique was practiced and where Dario had previously lived.[58] Some of the faces and possibly foliage (as in the Garden with Rose Trellis) could have been executed by a hand from the Vivarini workshop.[59] Finally, there are passages, such as the woman with the trailing white cape in the Departure, and the faces in lost profile, such as that of Helen in the Reception at Troy, that appear to draw on parallel solutions in the work of Piero della Francesca, as in The Legend of the True Cross in the Church of San Francesco at Arezzo (completed 1466) or his Madonna of Mercy, 1460–62 (Museo Civico, Sansepolcro), suggesting the participation of an unidentified assistant who had worked with Piero.[60]

Basic challenges to studying this painter resulting from the losses in his documented oeuvre are compounded by the multiple names by which he was and is known; however, these provide a brief itinerary of his career, reflecting the “gig” economy of his time (fig. 13).[61] He can be cited as “Dario da Pordenone,” referring to the town where he was born.[62] In the earliest known reference to Dario, concerning his entry into the studio of Francesco Squarcione in Padua in 1440, he is “Dario de Utino, filius Johannis, Pictor vagabundus”: Dario of Udine, son of Giovanni, a vagabond painter.[63] “Dario da Treviso,” referring to where he lived around 1449–1458 and where began to draw significant attention, is how he is known to Giorgio Vasari in his “Life of Andrea Mantegna” (1568), as well as to the seventeenth-century commentator Carlo Ridolfi. [64] In 1462 Dario is cited as “depentor de Asollo,” where he lived and worked around 1459–1466, the period in which his mature style came to the fore.[65] A posthumous citation of 1498 references “Darius pictor de Conegliano,” where he is documented between 1471 and 1477).[66]

Cities in the Veneto where Dario was active

The range of known commissions is wide, from entire chapels, altarpieces, portraits, and facades of palaces and churches, many for noble families.[67] He was paid for several jobs involving council chambers of the local governing magistrates (podestàs) including those in Bassano, Conegliano, and in the doge’s palace in Venice.[68] Like many successful artists of the time, he also carried out humble tasks; for example, in 1451 he touched up a polychrome wooden processional crucified Christ.[69]

Surveying Dario’s career for important, documented milestones offers a sense of the environments that shaped him and his profile for contemporary patrons. As this is not a survey of his artistic endeavors, attributed works of art referenced here are limited to a few projects from the years just preceding the Corner commission.

Although Dario probably received his initial instruction from his father, Master Giovanni, who remains otherwise unidentified, the major early influence on his artistic development was his years in Padua from 1440 to 1448, then one of the more fertile and diverse art centers in Italy. The period from 1440 to 1446 was spent as a pupil or salaried assistant of Francesco Squarcione (ca. 1395–after 1468), known less for his own paintings than for the tens of young artists who trained there and for his collection of antiquities, which he made available for study.[70] In the 1440s his students included the brilliant, ambitious young Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506; with Squarcione, 1440–1448), generating a competitive environment of which, according to Vasari, Dario was very much a part. In 1446 Dario was paid for his first known work, an important commission from the Basilica di Sant’ Antonio, the full-length Portrait of Bernardino da Siena (Museo Antoniano, Padua) representing the future saint after his death (1440) and prior to his canonization in 1450.[71] This project was also the first of many for a noble patron, Jacopo Pappafava.[72] The years 1446–1447/48 were spent in a partnership with the little-known Pietro de’ Mazzi, any products of which are unidentified.[73]

Beyond the stimulus of the workshop, there was much to absorb from the city’s active and varied artistic environment.[74] Looking back from the vantage point of the later 1460s and the Walters paintings, contacts made and approaches absorbed here remained with him throughout his artistic development. Artists practicing in Padua included Giovanni d’Alemagna (active in the city since the 1430s) and Antonio Vivarini, at work in the Ovetari Chapel in the Church of the Eremitani (from 1448), as were Niccolo Pizzolo and Mantegna, the latter subsequently taking over the project to create one of the most influential set of frescos of his time (see figs. 35, 36).[75] A strong conservative but stylish contingent encompassed Giovanni Francesco da Rimini (ca. 1420–1470) as well as numerous German sculptors and carvers. The imprint of Florence was significant: works by Pietro Lamberti and Filippo Lippi were to be savored, and in 1443, Donatello arrived, bringing a new way of thinking about space, architectural principles, and perspective to enhance narrative, represented by his sophisticated relief The Miracle of the Miser’s Heart (fig. 14) with its remarkable barrel-vaulted interior, completed around 1447 for the high altar of the cathedral. In 1445 he was joined by Paolo Uccello (1397–1475), who carried out a now-lost fresco cycle in the palace of the Vitalini family. To judge from Dario’s later surviving work, including the Abduction series, he was affected by these contemporary approaches, but also by the forceful characterization of form, especially of the face, seen in the great fresco cycles by earlier generations that abounded in Padua, as those in the Church of the Eremitani or the palace of the Carrara family by Guariento di Arpo (1310–1370).

Donatello (Donato di Niccolo di Betto Bardi, ca. 1386–1466), The Miracle of the Miser’s Heart, ca. 1447–48. Bronze, 22 7/16 × 48 7/16 in. (57 × 123 cm). Altar of the Basilica di Sant’Antonio, Padua

Of the works that can be assigned to Dario’s first decade after leaving Squarcione and settling in the less demanding environment of nearby Treviso, the most important are lost.[76] In 1456 he was commissioned to carry out the decoration of an entire chapel in nearby Quinto belonging to the Venetian admiral and member of the governing Council of Ten, Orsato Giustiniani (d. 1464).[77] Nothing remains beyond the documents; its loss for understanding the artist’s development is great, as the Giustiniani were one of the ancient noble families of Venice (with ties to the Corner); Orsato, as a wealthy, worldly member of the Council of Ten, could have employed someone better known. It was also in 1456, apparently as a result of the frescoed chapel for Giustiniani, that Dario was called to Venice to exercise his skills as a painter in the Palazzo Ducale, the most prestigious site for a painter in the Venetian Republic.[78] The two existing documents initially refer to the artist as “the painter who had painted the chapel of N. [nobile] H.[homo] Orsato Giustinian” (pittore che dipinto aveva la capella del N.H. Orsato Giustinian). The second, indicating that he has gone to Venice, mentions his name. This suggests that the invitation was to the painter recommended by a member of the Council of Ten. The surviving reports do not indicate what he was to paint; so possibly the job was not to paint but to re-paint. Given that the immense frescos of earlier generations, the glory of the spaces they occupied, were subject to decay from damp, which the authorities sporadically made efforts to address, it is conceivable that Dario, practiced in fresco, a medium no longer common in Venice, was called in to touch them up.[79]

In the decade preceding the Corner commission, much of it spent in Asolo (ca. 1459–1465), Dario’s style, as judged by the greater number of extant paintings assignable to this period, evolved into the mature manner manifested in the Walters paintings.[80] The major surviving project from this period attributable to him involved interior and exterior fresco decoration of the medieval church in Asolo now known as San Gottardo.[81] Only scattered, partial figures remain, but some of the saints’ heads establish a continuity of style with the later Walters paintings (fig. 15), as Edward King, writing in 1939, was the first to note.[82] Two heads offering the most compelling comparisons are those of St. Chiara in the grouping of St. Gotthard between Saints Bonaventure and Chiara, and that of a Franciscan, possibly St. Francis (?), looming above from what reads as a different (subsequent?) campaign also by Dario.[83] The chiseled features with the long nose extended into an arcing eyebrow are characteristic; when carried over into panel painting, they retain the strengthened features developed for fresco. Close by there is a further intriguing fragment that has gone undiscussed (fig. 16). Above the coat of arms (unidentified) is a portion of a man’s fur trimmed outer garment in a contemporary, secular style, potentially belonging to a figure (wearing a sword) “presenting” the coat of arms.[84] This distinctive treatment, identical to parallel passages in the Walters Abduction, provides a clear, specific tie between the two painting projects, virtually a little signature.

Dario di Giovanni, St. Gottardo between Saints Bonaventure and Chiara with St. Francis from a separate campaign. Fresco. Church of San Gottardo, Asolo. Photograph Fondazione Federico Zeri.

Left: Dario di Giovanni, fragment with a man’s fur-trimmed overcoat. Fresco. Chapel of St. Gotthardt, Church of San Gottardo, Asolo. Reproduced from Giorgio Fossaluzza, Gli affreschi nelle chiese della Marca Trevigiana dal Duecento al Quattrocento, Arte nelle Venezie 1.3 (Treviso, 2003), fig. 15.92. Right: Detail from the Abduction

That Dario’s repertory of facial types included ones retaining a sense of form inherited from the late medieval fresco tradition is reflected as well in a previously unrecognized collaboration with the Vivarini workshop that can be assigned to these years. The Polyptych with the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints in the Pinacoteca di Bari has been attributed to Bartolomeo or Antonio Vivarini alone or together.[85] The central panel of the Madonna and Child is indeed stylistically consistent with the work of Bartolomeo Vivarini, but the two extant side panels with Saints Benedict and Scholastica are by Dario, made clear through a comparison of the face of St. Benedict (fig. 17), forcefully defined by his long flat nose, with, on the one hand, the round fleshy face of Vivarini’s Madonna with lightly drawn features so influenced by the soft manner of his elder brother Antonio (see fig. 11), and, on the other, heads from the Walters Reception at Troy. This collaboration of independent masters opens the door to considering the possibilities of such relationships elsewhere, as in the Abduction series.

Left: Dario di Giovanni, St. Benedict, detail of Polyptych with the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints. Tempera and gold leaf on poplar, 49 1/4 × 10 3/8 in. (125 × 26.3 cm), Pinacoteca “Corrado Giaquinto,” Bari . Center and right: details from Dario di Giovanni and collaborators, The Reception of Helen at Troy.

The largest surviving project attributed to Dario prior to the Corner commission was carried out in Pordenone, the city of his birth, probably around 1466, as Dario was recorded as briefly back in Padua then and would have spent time in the Ovetari Chapel (completed in 1457), which experience appears to have informed his compositional solutions in Pordenone.[86] The frescoing of the chapel of the Popaite family dedicated to the life of St. Nicholas in the Cathedral of St. Mark (fig. 18) was a significant commission and in its pristine state must have been spectacular.[87] The Popaiti were raised to the nobility in 1447 by Archduke Albert of Austria, who held Pordenone as a Habsburg enclave. The male family member portrayed as the donor may be Antonio Popaite, podestà in 1466 and 1469.[88] The frescos were partially destroyed in the late sixteenth century.[89] While some of the faces (including that of the donor) are reconstructions, the compositions retain their original vigor. No documents concerning the decoration are known to survive. While the attribution to Dario by Coletti and then Furlan was not taken up in the following years, no alternative has been proposed, and he remains the only viable candidate. The approach that pervades the compositions of the extant scenes looks back both to less adventuresome segments of the Ovetari chapel by Ansuino da Forlì and Niccolo Pizzoli, as Furlan pointed out, and forward to the Walters series, as that astute observer was also aware.

Dario di Giovanni, Episodes from the Life of Saint Nicholas (with the death of the saint) from a cycle on the Life of Saint Nicholas, ca. 1463–66. Fresco. Chapel of St. Nicholas, Cathedral of St. Mark, Pordenone.

From 1468 to early 1471, the timeframe within which Dario would have executed the paintings for the Corner, his base was again in Treviso until the completion of an altarpiece (lost) for a local noble family, the Betignoli.[90] That year he was in Conegliano, beginning a major commission for an altarpiece and the frescoing of a chapel there (now lost).[91] The last reference to him there as alive is from 1477, but the last known commission is from around 1474 for a signed fresco of the Madonna and Child for the facade of a house belonging to the Lusignan family, “del re di cipro” (of the king of Cyprus).[92] Thus Dario’s last known major commission was for the family for whom the portrait of Caterina—the point of departure for the Walters Abduction series—was painted.

The Abduction of Helen Series as an Istoria

In the later 1400s in Italy, the representation of an istoria, a story or narrative of exemplary nature, whether of historical events or from ancient mythology, was considered the greatest challenge for a painter.[93] The challenge came not only from the need to do justice to an uplifting or moral message but also from the necessity of depicting significant human actions in such a persuasive, varied, and pleasing way that the viewer fully engaged with the intended meaning. In the first pages of her fundamental work piecing together the nature of monumental narrative painting in fifteenth-century Venice, Patricia Fortini Brown underlined the importance of storytelling:

“Even when masquerading as entertainments—fables, romances, secular dramas, ‘naïve’ paintings—they function as mediating devices that help people to deal with the indeterminacies and insufficiencies of the real world. . . . Real events are untidy and incomplete in comparison to the stories we tell (or paint) about them. Narrative forms can make ambiguities tolerable, provide linkages and give structure to amorphous happenings. To confer coherence, wholeness, closure, and—perhaps most importantly—moral significance on the events that clutter our imperfect world, it is essential to narrate.”[94]

The Walters Abduction of Helen series exemplifies this characterization. Behind it, there are indeed untidy but important family stories to be rendered coherent. The family’s insistent claims on the Roman gens Cornelia and the virtues of Scipio Africanus underline a desire for coherence.[95] The choice of the abduction of Helen as the vehicle celebrating the marriage of Caterina fits into themes, based on historical and literary circumstances, that negotiate the dialogue between past and present that such storytelling does so well: the importance assigned to the Trojan War in Venice, to a woman’s irresistible beauty, and to associations between the island of Cythera, where Paris and Helen met, and Cyprus, where Caterina and Jacques would meet, both islands dedicated to Venus as goddess of love.[96]

The Trojan War (twelfth century BCE) was a popular subject for art in elite circles in Europe in the 1400s, particularly in tapestries and illuminated manuscripts.[97] Today it is a commonplace to think of Renaissance European culture in terms of a revival of Greco-Roman culture, but for the great courts of the period where most of the major commissions addressing secular history were generated, it can be argued that the perception of the historical (versus the cultural) continuum was not Greco-Roman but Trojan-Roman. In the 1400s, the history of Troy was fundamental to the sense of local and national history in many parts of Europe. While Roman culture owed its greatest debt to that of Greece, the ten-year Trojan War, in the persons of Trojan princes Aeneas, Antenor, and Francion fleeing their destroyed city in present-day Turkey, was understood to have been of extraordinary impact, precipitating the founding of Rome and of many of Europe’s other chief cities including Paris, London, and Venice.[98] By comparison with the giant explosion that physicists conclude initiated the evolution of our universe, this was the “big bang” of European history, and Paris first locking eyes with Helen was the initial spark.[99]

The fabrication of Venice’s foundation myths of Trojan origins as an aspect of identity—through Antenor, his followers (said to be the Heneti or Eneti [=Veneti], one of the tribes historically in the area) and descendants finding refuge first in Padua and then on the islands in the lagoon—was largely a work of the eleventh to thirteenth centuries. During that period, the city gradually extricated itself from the embrace of the Byzantine Empire (finalized by Venetian participation in the sack by European forces of Constantinople, its capital, in 1204) to become a major maritime force on the Adriatic.[100] Venice was the only city of significance in Italy that was not built up from a pre-existing Roman town; as it came to prominence, noble, older origins were sought elsewhere.[101] By the mid 1400s, while Trojan origins were beginning to be treated as myth by some, by others they continued to be treated as history.

The continuing appeal of the myth of Trojan origins is seen in the writings of two Venetian historians of the 1490s. In the opening pages of his celebratory On the Origins, Situation, and Government of the City of Venice (De origine situ et magistratibus urbis Venetae), composed around 1493, Marin Sanudo, the well-connected Venetian diarist and historian, references the city’s chroniclers and the authority of earlier historians.[102] While acknowledging the presence of Cisalpine Gauls in the region, he underlines the nobility of the Trojans who previously settled the area.[103] Later in the text, the author applied his sense of the adversities faced by the noble Trojans to the Corner family, comparing the burning of the family palace now known as Ca’ Corner della Ca’ Granda in 1532 to the burning of Troy.[104] Sanudo’s contemporary, the historian Bernardo Giustiniani (1408–1489), in his History of the Origins of the City of Venice (De origine urbis Venetiarum . . . , 1492), diplomatically proposed that both Gallic tribes and Trojans contributed to the region’s character and development.[105]

In the 1400s, “the abduction of Helen,” as an independent subject, was clearly deemed appropriate to celebrate a marriage; it is depicted on marriage-related items both in Venice and Florence.[106] The most striking representations are on Florentine cassoni or marriage chests, exemplified by Liberale da Verona’s Abduction of Helen, ca. 1470 (fig. 19) and that by Apollonio di Giovanni from about 1465 (fig. 20).[107] Cassoni were commissioned by the groom’s family and reflect prevailing societal (i.e., male) views on marriage and civic virtue: that a bride should be irresistibly beautiful, as was Helen. That a bride should also be so passionately desired, as was Helen, as to precipitate violence was perceived as a compliment.[108] In contrast, Flemish tapestries, the medium of public presentation with the greatest number of representations of the Trojan War in the 1400s, consistently privileged the high drama of the battlefield, as appropriate to their general propagandistic function.[109] The tapestries were generally executed in series, first for members of the French and English royal houses, proud of their Trojan heritage but also of a life in arms. Tapestries of individual episodes are recorded, but there appears to be no evidence that the abduction was popular for this format.[110]

Liberale da Verona (ca. 1445–ca. 1526), The Abduction of Helen, ca. 1470. Oil on wood, 16 1/8 × 43 5/16 in. (41 × 110 cm). Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Apollonio di Giovanni (ca. 1415 or 1417–1465), The Abduction of Helen, ca. 1465. Tempera on wood, 15 3/4 × 60 3/4 in. (40 × 153.6 cm). Private collection, formerly Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photograph courtesy Sotheby’s

In the Renaissance, beauty—erotic beauty—was a woman’s primary claim to excellence, as it had been for the Greeks. Helen, the most beautiful of mortal women, epitomized this notion in antiquity. The first Renaissance treatise consisting of biographies of the “illustrious” or famous women of the past (De claribus illustribus) by the Italian humanist Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375) also praised Helen for the undoubted excellence of this natural gift. In the Greek myth of the Judgment of Paris (the “prequel” to the abduction), Minerva and Juno, otherwise intelligent and powerful goddesses, feel it necessary to contest the title of “the most beautiful” with Venus, goddess of erotic beauty.[111] Homer, the great wordsmith, had difficulty putting the effect of Helen’s beauty into words, but for many other subsequent (and lesser) authors—such as Guido delle Colonne, the main source for the Walters series—it was easier just to list her features.

Then there are appealing connections between the island Cythera, dedicated to Venus as her birthplace, where Paris and Helen first meet and their passion was ignited, and the island Cyprus, also dedicated to Venus as her birthplace, where Caterina Corner would join her husband. In some versions of events familiar to Renaissance scholars, Paris and Helen stop in Cyprus before reaching Troy.[112] Both Helen and Caterina are compared to the goddess: Helen was said to have been as beautiful as Venus, and the same was said of Caterina, who would be acclaimed in Cyprus as the “very goddess in beauty.”[113] In a transparent repurposing of the Judgment of Paris, the earliest biography of Caterina included a charming but nonsensical story to the effect that Venetian families had committed their daughters to a beauty contest, at which Caterina was selected as the most beautiful and therefore as the prospective queen whose portrait was to be sent to the young king.[114] Then there is the delicate poetic salute to Caterina Cornelia as a bride (written around 1468–1474) by the poet Bartolomeo Pagello in which Cytherea (Venus) brings jewels from Cyprus as tribute to Caterina as wife and queen.[115] These more idyllic qualities of Cythera as an island for lovers would come to mind in the separate chamber where one would be surrounded by Dario’s two-part Garden of Love ensemble (see figs. 3, 4), reflecting the tenderness and playfulness of the medieval courtly tradition of the delights of the enclosed pleasure garden, modulating the more overtly erotic urgency of the abduction.[116]

The Textual Sources

In addition to Homer, the abduction of Helen, queen of Sparta, by Paris, prince of Troy, was described with varying details and assumptions by tens of authors in antiquity and many others over the centuries prior to the 1460s.[117] Almost all authors shared the assumption that this abduction, however it came about, led to the ten-year war waged by Greeks against the Trojans to get Helen back and that resulted in the destruction of the great city of Troy and the dispersal of its peoples.[118]

In Italy in the 1400s the most respected version of the Trojan war as history—and the one exhibiting the most similarities to Dario’s paintings—was Guido delle Colonne’s History of the Destruction of Troy (Historia destructionis Troiae) of 1287, which was widely available through countless manuscript copies.[119] The author states that his account is based on two ancient texts describing events of the war, both by men who claimed to had been personally involved: Dares the Phrygian (Trojan) and Dictys of Crete (Greek). Homer’s Iliad was rejected out of hand as riddled with “falsehoods,” for describing the gods as fighting alongside humans and as having been written long after the events described.[120] In fact, Guido’s primary source for his purportedly historical account was a famous French romance by Benôit de Sainte-Maure, Le roman de Troie (written around 1160), which in turn was actually based on the (pseudo) historical texts said to be by Dictys (Greek original of the first century known from a Latin version of the fourth century CE) and Dares (again Greek original of first century known in a Latin version of the sixth century CE) with many fanciful details.[121] Guido’s Historia was generally perceived as a serious work of historical writing, although by the mid-1400s doubts were beginning to be raised.[122]

According to Guido’s account of the abduction of Helen (Books 6, 7), diplomatic efforts by Priam, king of Troy, to persuade the Greeks to return his sister Hesione, who had been abducted by the Greeks and treated as a concubine, had been unsuccessful. He told a council of princes that he wanted to try again and was ready to use force to at least achieve vengeance, but the fact of Greek military advantage caused many of the princes to counsel caution. Priam’s son Paris, however, called for action. He was certain that the gods wished him to defeat Greece and to “seize some very noble woman from the aristocracy of Greece and bring her captive to the Trojan kingdom” to be exchanged for Hesione. He declared to have received a “sure sign” from the gods themselves. In a dream, the god Mercury brought before Paris three goddesses—Venus, Minerva, and Juno—so that he might decide their quarrel as to which one was the most beautiful, a result of a “wonderful apple of precious material” inscribed “to the most beautiful” having been thrown among them. Mercury described what each goddess offered him to choose her: Juno (queen of the gods), that she would make him the greatest man in the world; Minerva (goddess of wisdom and war), that she would grant him all human knowledge; and Venus (goddess of love and sex), that she would let him “carry away from Greece a very noble woman, more beautiful than Venus herself.” He chose Venus, who confirmed her promise, upon which he awoke. So Paris asked Priam to send him “against Greece” to “bring back the woman with me, according to divine promises.”

Heedless of warnings of dire consequences, the ships struck out “in the name of the gods Jupiter and Venus.” Before reaching the Greek mainland, they came to the island of Cythera, under Greek control, and went ashore. On the island there was a wonderfully beautiful, rich, ancient temple dedicated to Venus, in whose honor a festival was underway. The Trojans, dressed in gorgeous attire, went to the temple and made offerings. Paris told those he encountered at the temple that he had come to find his father’s sister. His listeners were struck by his beauty and “regal pomp,” word of which reached Helen. Seized with fascination, she wanted to see him for herself. Her husband, Menelaus, was away. Declaring that she wished to fulfill some vows, she arranged to make the trip. “In royal attire and with her retainers,” she rode her horse to the shore and embarked for the short journey to Cythera, where she was received “with great honor” and went to the temple to fulfill her vows to Venus.

When Paris learned of Helen’s arrival, he went there as well. Animated by intense desire, he contemplated every aspect of her appearance beginning with her “thick golden hair, which shines with radiant splendor.” Their eyes met, and they revealed to each other through signs their mutual passion. Paris took his leave and returned to the ship, telling his men that it would be impossible to recover Hesione but that they could attack the temple and take away riches and many captives including the queen, Helen, who could be exchanged for the king’s sister. When night fell, the Trojans returned to the temple and attacked. They looted everything and took everyone captive. Paris captured Queen Helen “with his own hand.” She did not resist but was “animated by consent.” The tumult was such that the clamor reached the fortified castle “on a higher place above the temple,” the armed residents of which fell on the Trojans but were outnumbered. The Trojans set sail and arrived on the shores of the Trojan kingdom. Helen, among the captives, was “tormented with great anguish,” and Paris could hardly comfort her. Paris insisted that she had nothing to fear, that her rank would be respected and that as his wife she would enjoy great dignity. Priam sent her “royal garments” and, mounted on a handsome horse, she proceeded with the others to Troy, where they were met by Priam with a “retinue of many nobles” and other celebrants. He led her into his “lofty palace.” Paris and Helen were married the next day.

Guido’s text was sufficient for the basic narrative, while other sources may have provided details. Combining elements from a variety of literary sources to produce the cogent, innovative version reflected in the Walters paintings would have been the work of an advisor, a scholar who would have been familiar with the literary options or how to locate them. The best candidate is Paolo Marsi (1440–1484), a young but respected humanist hired by Marco Corner as his son Giorgio’s tutor.[123]

Representing the Story

Dario’s Abduction spalliere charm viewers now, as they must have done when painted, by engaging the imagination through a combination of an accessible narrative, clear staging, the glamor of magnificence, intriguing detail, and humor without sacrificing dignity. Lorenzo de’ Medici, one of the great patrons of art for the private palace, was insistent that, along with other factors, including the skill of the painter, the subject matter (le cose depinte) should please in itself (sè diletti).[124] Beyond drawing on Dario’s own past environment and projects in Padua, Pordenone, and elsewhere, the visual characteristics of the Walters series, along with the other paintings that were part of the same extended commission, suggest that he and his collaborators drew on qualities associated with the two major workshops then active in Venice: the panache of sumptuous textiles and luxurious foliage that had characterized the earlier altarpieces of Antonio Vivarini and Giovanni d’Alemagna for churches in Venice and Padua, and the perspectival staging of historical events and imaginative adaptation of Roman ornamentation characteristic of Jacopo Bellini and carried on by his sons.[125] Unfortunately, all the earlier fifteenth-century large-scale, complex history paintings commissioned from such luminaries as Pisanello, Gentile da Fabriano, Giovanni d’Alemagna, Antonio Vivarini, and then, more contemporaneously, Jacopo and Gentile Bellini to cover the walls of the great meeting chambers in the ducal palace or in the halls of various religious institutions that Dario may well have studied are now all lost, primarily through fire or damp.[126] Nevertheless, the influence of Jacopo Bellini (ca. 1400–ca. 1470) can still be gauged in some degree from his two famous existing notebooks (Musée du Louvre and British Museum), filled with compositional studies for istorie and now dated to the 1430s into the 1460s.[127] Two of the three Walters panels respond to features of Jacopo’s compositional formulas developed in the notebooks.

In working out a persuasive narrative, Dario employed architectural and sculptural references to evoke the distant past, even as Helen and the other young men and women are resplendent in their Renaissance fashions. While a student of Squarcione, Dario would have had access to a range of sources, including collections of Roman works of art (beginning with that of Squarcione himself), which in most cases can no longer be assessed. In addition, Dario appears to have had the opportunity to consult the Paduan scholar Giovanni Marcanova’s influential antiquarian manuscript Collection of Antiquities (Collectio antiquitatum, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena) completed in 1465 (known in multiple fifteenth-century copies).[128]

The paintings appear to have been conceived both as an integrated composition, of which the landscape components, set against the same banded sky (blue to nearly white above the horizon) flow successfully from one panel to another, and as discrete images with their own internal cohesion.[129] Within the integrated composition, the overall narrative or story line is staged almost as a procession, unfolding from left to right. By comparison, istorie for Florentine cassoni often involve a triumphal procession, most commonly either allegorical, as the Florentine Triumph of Venus (Walters Art Museum) from around 1500, or from ancient history. But when the istoria consists of a series of episodes over time—as does the Walters Abduction—the spatial disposition of the figures is normally varied, as in Apollonio di Giovanni’s Abduction of Helen (see fig. 19), engaging the eye in the kind of treasure hunt praised by that discerning viewer, Lorenzo de Medici.[130]

The underlying symmetry introduced to integrate the combined setting of the Abduction ensemble offers a beginning and conclusion, each defined by a sturdy architectural “bookend.” The procession sets off against a backdrop of the massive city walls of the city-state Sparta, moves through an open area of encounter and conflict identifiable as Cythera, and arrives in an architecturally defined interior space, the courtyard of the royal palace at Troy, where Helen kneeling before the king and queen of Troy brings the narrative as well as the action to a full stop. Depicting Sparta as the point of departure within the same composition as Troy is unusual, but it creates an easily grasped “journey” narrative. The brilliance of this solution is underlined by comparison with the ultimate distillation of the abduction in an anonymous German woodcut (fig. 21) from 1473 illustrating the life of Helen in the first printed edition of Giovanni Boccaccio’s Lives of Famous Women (De claribus mulieribus): Paris comforting Helen on a ship tucked between the walls of “Lacedaemon” (the kingdom of which Sparta was the capital) and Troy.

German, The Abduction of Helen, illustration to “Helen, Wife of King Menelaus” in Giovanni Boccaccio, De claribus mulieribus (Ulm, 1473). Woodcut. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, bequest of Henry Walters, acc. no. 91.243

In the first panel, Queen Helen—identified by her ruby hair jewel and as the woman abducted in scene two—is surrounded by her entourage of young women, two girls, and three men bringing up the rear, before the gate and walls of Sparta (fig. 22). They stroll toward the ship that will take them to the island of Cythera, a protectorate of Sparta dedicated to Venus (and in real life a Venetian possession), to participate in celebrations honoring the goddess. The party is beckoned toward the ship by a grinning buffoon or jester in typical yellow costume and donkey’s ears who appears to be playing the part of guide, implying that mischief lies ahead.[131]

Dario di Giovanni and collaborators, The Departure of Queen Helen and Her Entourage for Cythera, ca. 1468–69. Tempera and Pressbrokat on spruce, 60 × 94 3/16 in. (152.4 × 239.2 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, bequest of Henry Walters, acc. no. 37.1178

The figures are all dressed in expensive fashions of contemporary Venice while the more rigorous, approach to antiquity–ancient figures in ancient dress–would be the preference of Giovanni Bellini in his Continence of Scipio Africanus, ca. 1507 (see fig. 5), commissioned by the Corner family in honor of their Roman forebear. However, the Corners’ Abduction series was surely intended to negotiate the borders between history and present experience–and for Venetians, the experiencing of great events involved great clothes.[132] Marin Sanudo’s comments on the great civic rituals of Venice that constituted the nobility’s expression of communal magnificence often included the clothes that made them memorable: “it was a beautiful thing to see so many garments of silk, velvet, damask, and satins, and scarlets.[133]

The presentation of these young men and women is strikingly sumptuous. The women are fashionably but decorously dressed, wearing dresses with long trains (known generally as a gamurra, but called zupa, zipa, or socha in the north of Italy) and fur-lined or trimmed cloak with hanging sleeves (pelanda in Venice).[134] The effect is dependent less on the women’s jewels, which are rather restrained, consisting of ropes of pearls, a jeweled collar, or perhaps a single but large ruby hair jewel, as that worn by Helen, than on the the simulated brocades, shimmering with the effect of gold and silver threads, which in their original condition would have been astonishing in their visual effect.[135] The delight in display and the focus on the luxurious, tactile effect of the brocade is distilled in the elegant and alluring figure of the young woman depicted from the rear, drawing the viewer’s eye to the brocade for its own sake.[136] The men wear fur-(ermine) lined and/or fur-trimmed open-sided tunics (giornea) or overcoats with hanging sleeves (gonnella or cioppa) over their doublets (known by different terms such as giubetto, zuparello, or farsetto) into which they laced colorful hose (calze).[137] They must be under twenty-five, because it was at that age that they gave up colorful clothing for the sober black that signified their participation on the Great Council.[138] Venice was known for its sumptuary laws, which were intended to curb such display, especially of women’s clothing and jewels.[139] However, regulations were reduced or suspended in so many situations, such as weddings or any public event intended to impress foreign dignitaries, leaving scholars to conclude that they were not particularly efficacious.

The painting also reveals contemporary preoccupations with hair. Beauty, certainly irresistible beauty, required golden blond hair: all the women depicted in the panels have some variation of it.[140] Helen, as described by Guido delle Colonne (and virtually all authors) was endowed with golden hair; the beautiful St. Catherine of Alexandria, Caterina’s name saint, as well as the Virgin, and female saints in general were depicted as blonds at this period; it was the default attribute of female virtue as well as erotic intrigue. The formative, contemporary model for the latter was found in the writings of the influential early Renaissance humanist Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374), who had lived for some years in Venice. His sonnets in celebration of his beloved muse, Laura, and the enticing tendrils of her golden hair were engrained in the mind.[141] Not all blondes were naturally so—the effort entailed in meeting this cultural expectation is revealed in Janet Stephens’ note on a Venetian book of beauty tips from the period. The varied hairstyles of the women in Helen’s party all involve a high forehead with the hair secured atop the head with a little harness of pearls (frenello). While the assumption has been that such styles (versus freely hanging hair) indicate the married state, the older of the two girls in the painting is similarly coiffed. In the absence of a Venetian source from the 1400s, I hesitate to ascribe a marital indicator to these careful managed hair styles beyond the modesty thought appropriate for all adult women out in public.[142] However, the large ruby head brooch worn by Helen (and a smaller one worn by a second woman) may serve as such an indicator; rubies were frequent gifts to brides, intended to promote health and moderate lust.[143]

Other details in the painting—a yellow ball, handkerchiefs, little girls, animals, and flowers—enliven the scene and add their own nuances. The yellow or golden ball that the lady with the dagged white cape has in her hand, ready to be offered to Helen, could be a reference to the kind of courtly ball game played by ladies and gentlemen that figures in domestic palace decoration from the Venetian terrafirma.[144] It could also be a clever reminder (under the veil of a leisure pastime) of the Judgment of Paris, with which the story of the abduction began, and the golden apple or ball (often the latter in Italy) engraved “to the fairest” that was Venus’s prize (see Stephens, “Becoming a Blond,” fig. 4).[145]

Two of the young women play with their handkerchiefs, a ubiquitous possession. A young woman uses hers to blindfold a young man in the Melbourne Garden of Love (see fig. 3). Cupid himself may be shown blindfolded and bound by a personification of Chastity or even Venus herself, suggesting, among other possibilities, that once bound in marriage, one should cease looking.[146]

Also shared with the Garden of Love is the motif of a young woman cradling a small white dog.[147] A lapdog that is a much-caressed playfellow is a more likely reading in both paintings than a white ermine as a symbol of chastity, the identification proposed by Edward King.[148] The lithe Italian white whippet or greyhound is stretched out at full speed, the characteristic pose favored for the many representations of the species. Greyhounds were commonly owned as hunting dogs, and here the hound is on the scent of “game,” possibly a humorous reference to Paris and Helen about to converge on Cythera. The rabbit diving into its hole in the lower left may be simply fleeing the greyhound, but, through its fabled fecundity, it is closely associated with Venus.[149] On the other hand, the carpet-like patches of red clover, along with oxalis and dandelions (just the leaves), may simply be delights for the eye.[150]

Two girls, dressed and coiffed similarly to the young women, provide a rapt audience for the tambourine-shaking buffoon/jester. Painters usually chose boys as curious onlookers at processional or parade-like events.[151] This rare instance of girls as onlookers may allude to Caterina’s younger sisters.

The setting consists of three elements that each support the narrative: the walls of Sparta, a massive outcropping of rock, and the waiting ship. The walled city is identifiable as Sparta only by being the departure point for Helen and her party. There are no rooflines of known monuments visible over the ramparts (as there would be of an image of Rome in Florentine painting), though there is a Venetian chimney.[152] For all the reverence humanists offered up to Aristotle and Plato, there was little interest in the representation of their homeland per se.[153] The aim here was not accuracy but a dignified staging point for the istoria. The ahistorical addition of balls for architectural embellishment, also found in the other scenes, was most likely adapted from the fanciful renderings of Roman architecture in the pages of Marcanova’s Collectio, for example, An Equestrian Statue (Marcus Aurelius) in a Fictive Roman Setting (fig. 23).[154]

Paduan, An Equestrian Statue (Marcus Aurelius) in a Fictive Roman Setting. Pen and ink on vellum, 13 3/8 × 9 7/16 in. (34 × 24 cm). From Giovanni Marcanova’s Collectio Antiquitatum, before 1465. Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena, Lat. 992, fol. 29v

From the city gate, Helen and her party cross before a fantastically peaked outcropping of rock fronted by figures on a rigid plane, as developed by Jacopo Bellini through studies in his notebooks, exemplified by his Martyrdom of St. Christopher (British Museum) or his Adoration of the Magi (Musée du Louvre). Untamed nature is softened by a row of shrubbery that sets off the rich textures and colors of the fabulous clothing on display before it. [155]

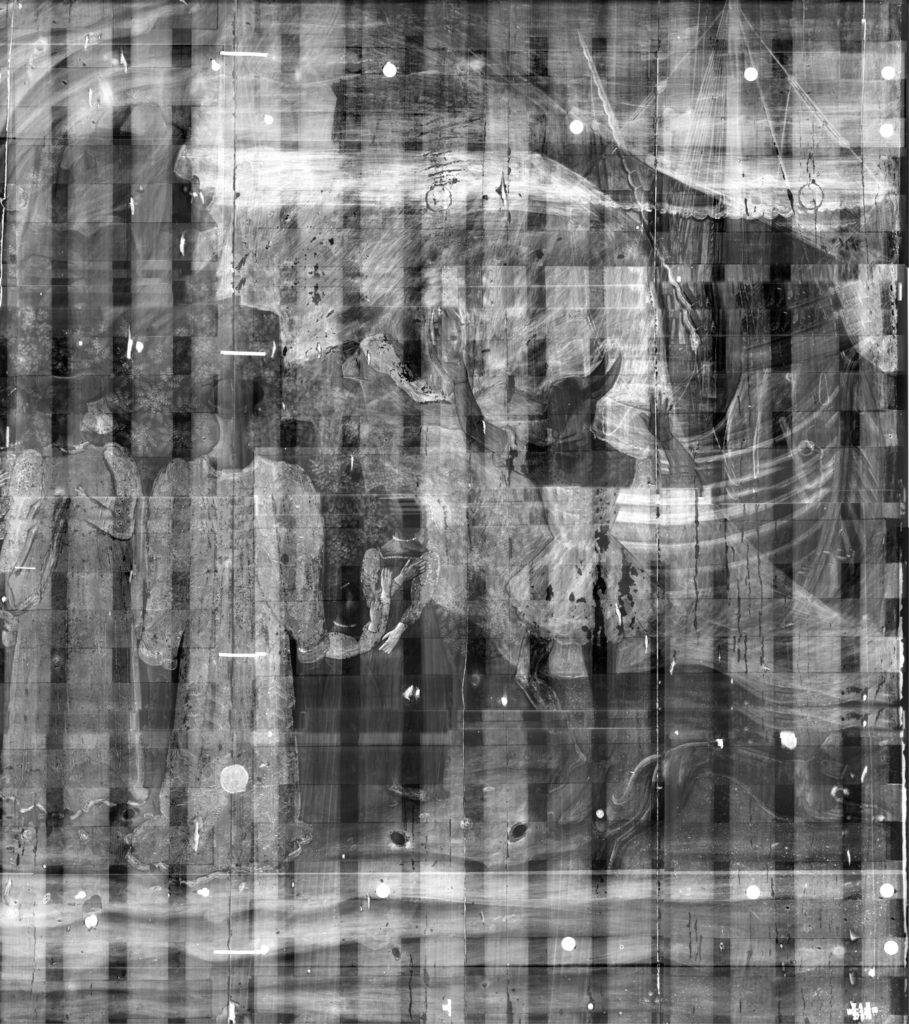

Helen’s waiting ship represents a type of Venetian three-masted merchantman commonly to be found in the harbor, as one being repaired in a detail from Breydenbach’s well-known panorama of Venice from Peregrinatio in terram sanctam (fig. 24).[156] It has a rounded hull that was excellent for transporting goods (or men) and had no counterpart in antiquity. The vessel is drawn in reasonably good perspective but exhibits odd characteristics that reveal Dario’s inexperience with depicting ships: for example, it rides surprisingly high in the water, and there is no crew. The pennant flies from the rigging rather than where it would be expected, the top of the mast, but the mast is cut off by the upper edge of the panel.[157] While the panel gives evidence of having been cut down along the top, it is unlikely that it originally extended sufficiently to allow for a proper crow’s nest. Since the pennant is important, its placement suggests a “fix” for a miscalculation. As demonstrated by an x-radiograph image of the right half of the painting (fig. 25), previously only the ship’s bow and forecastle were represented, pushing invasively in toward the shore.[158] A similarly aggressive use of a ship’s forecastle is featured in an Abduction of Helen (before 1476) attributed to Giovanni di Ser Giovanni, known as lo Scheggia (fig. 26), but the similarity is coincidental, reflecting the ease of depicting a ship in profile versus in perspective. Moving the ship back permitted a more complete portrayal that did not upstage the narrative or sever its flow.

Erhard Reuwich (ca. 1455–ca. 1490), Panorama of Venice (detail). From Bernhard van Breydenbach, Peregrinatio in terram sanctam (Mainz, 1486). Woodcut. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, bequest of Henry Walters, 1931, acc. no. 91.283

X-radiograph of the right side of Dario di Giovanni, The Departure (fig. 6), showing the initial placement of the ship

Giovanni di Ser Giovanni, known as lo Scheggia (1406–1486), The Abduction of Helen, 1460s. Tempera on wood, 15.7 × 18.8 in. (40 × 48 cm). Narodni Galerie, Prague. Photograph © 2019, National Gallery, Prague

The ship flies a pennant bearing a large “C” (fig. 27). In 1939, Edward King proposed that it might signal “Cythera,” a reasonable identification given how little was then known about the paintings.[159] As the pennant normally signaled the individual in charge, in the story that would be Queen Helen, but here she is the avatar of Queen Caterina. The single initial is usually that of a sovereign who can legitimately use just the first name, as “H” for Henry VIII, king of England or “A” for Anne, duchess regnant of Brittany, a contemporary. I propose that “C” is for Caterina.[160]

Dario di Giovanni and collaborators. The Departure: detail of pennant

The prominence of the merchantman may also allude to the importance of maritime trade for Venice (including members of the Corner family engaged in the sugar trade), much as would the veritable catalog of Venetian shipping found decades later in the background of Vittore Carpaccio’s imposing series The Legend of St. Ursula for the Scuola of St. Ursula (Gallerie dell’ Academia, Venice). This is an ancient type of vessel that continued to be used in the later 1400s for military and commercial purposes.[161] It also invites a contrast with Paris’s low-slung oared galley in the scene of abduction.

Tumult stretches across the second panel, the scene of the actual abduction (fig. 28), its mood of stress and confusion contrasting with the lightheartedness of the departure. The erotically charged moment of Paris and Helen locking eyes in the temple of Venus during the celebrations honoring the goddess is in the past, but Paris’s action in taking Helen by the wrist (not her hand) is a discreet but clear gesture with a history going back to the depiction of abduction scenes on Greek vase painting to convey the notion of a woman under the control of another, sometimes against her will.[162] In a not so dissimilar situation, many representations in Florentine painting of a woman being taken by the wrist are of a woman being given in marriage, in which instance control is passed from one man to another. Most versions of the abduction story make it clear that Helen was willing. As Dario has depicted her with downturned face, he may be drawing on a description of Helen in the mid-1300s Italian version of the story, The Trojan (Il Troiano) in which this body language is described as reflecting Helen’s embarrassment at feeling caught between her desires and her sense of duty.[163] As the paintings celebrate the wedding of a young girl who is surely thrilled at the romantic notion of being swept away to join the king, her husband, addressing the abduction with discretion that emphasizes more the attractions of the young woman than the act of being carried off seems appropriate. This restraint is at odds with the violence in Liberale da Verona’s Abduction of Helen, ca. 1470, for a cassone (see fig. 19), that by Lo Scheggia (see fig. 26), or the birth tray by Zanobi Strozzi in which Paris literally carries Helen off with no concern for her dignity. Of course, as discussed above, even this interpretation was considered a compliment to the bride’s essential attractions.

Dario di Giovanni and collaborators, The Abduction of Helen from Cythera, ca. 1468. Tempera on spruce, 60 3/8 × 116 1/4 in (153.3 × 295.2 cm). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, bequest of Henry Walters, 1931, acc. no. 37.1179

The narrative focus is on Helen’s stressed but calm exit to the right, toward the Trojan galley, but this is balanced visually by the shock and confusion spreading among Helen’s ladies, the signature exchange being that of the young woman near the center wrenching herself away from her pursuer. Everyone is still dressed splendidly, as they were for the temple celebrations, in contrast to versions of the narrative in which the Trojans come back at night fully armed for a fight. In addition, keeping to the underlying decorum of a wedding, the Trojans are not shown looting the temple.[164]