A child, ill equipped for the cold, sleds past gnarled black trees, while in the distance a blizzard swirls around the spires of a church framed against a winter sky (fig. 1). The distinctive architecture of that snow-swept city is recognizable as Halle, Germany, and it is probably there that the story of an extraordinary work of art unfolds.[1] The painting is one of forty-three, found in a book that was not meant to be illustrated, created by artists who may not have been illuminators, and commissioned by a family who should not have wanted them. It is a story of transformation and personal faith, and the Walters’ recent acquisition of this unique book will allow this fascinating tale to be rediscovered and shared for the first time in four centuries.

City of Halle with Child Sledding. From Jakob Zader, Die schöne Sommerzeit, 1603, with images added 1613–16. Ink, paint, and gold on paper, 5 7/8 × 3 1/2 inches (14.8 × 9 cm). Museum purchase with funds provided by the bequest of Margaret Hammond Cooke, 2017, acc. no. W.937, no. 6

The book, which was purchased by the Walters in 2017 and now bears the accession number W.937, is a remarkable work of Lutheran art with no known parallel.[2] It is a hybrid object that began as a simple, unillustrated printed book, published in 1603. A rare publication in its own right—only one other copy of this edition is recorded—it is an original work by the German theologian and Lutheran pastor Jakob Zader (1555–1613).[3] The text, Die schöne Sommerzeit, is an allegorical treatise in which the difficulties of life are compared to the hardships of winter, and the pleasures of the afterlife likened to the warmth and joys of summertime. This understanding of God’s message through the lens of the mundane was important and popular among Lutherans in this period. Zader’s theological training in Wittenberg, home to Martin Luther and the crucible in which the Protestant Reformation formed, undoubtedly had a profound impact on his philosophy and views on religion.

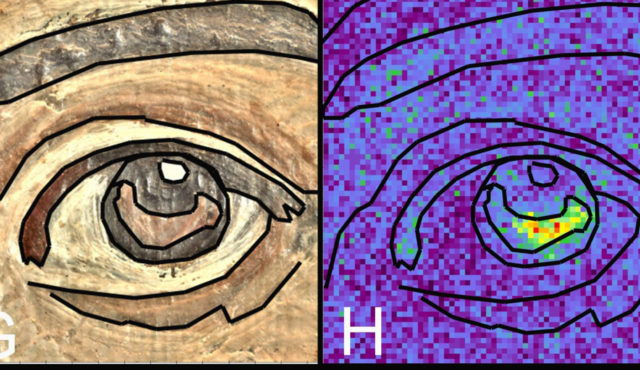

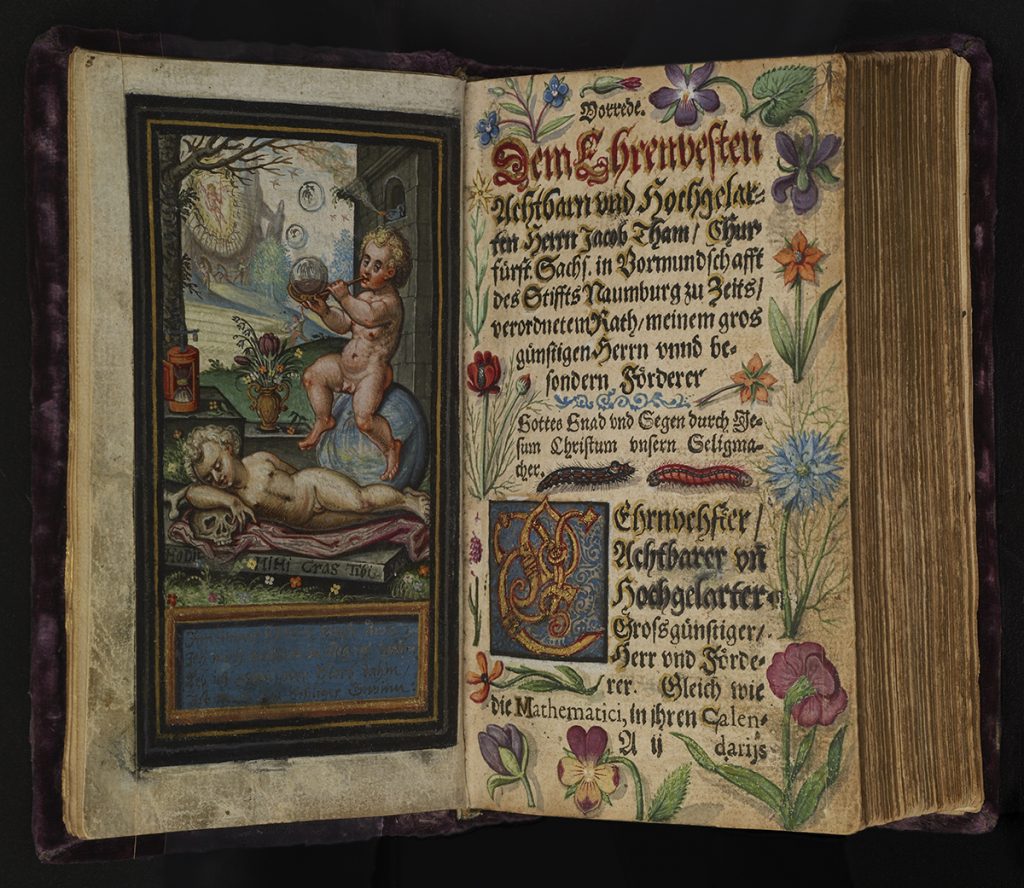

Zader’s book was typical in its lack of illustration, for Protestants in the sixteenth century were turning against extravagant art as a way to set themselves apart from the perceived excesses and monetary corruption of the Catholic Church. While Lutherans were not iconoclasts, they kept their art simple, and when book art did appear, it was typically minimal and printed in stark black and white.[4] It is therefore unexpected, and even shocking, that in 1613, the year of Zader’s death, this book began to undergo a remarkable and perhaps even inappropriately lavish transformation. Two as-yet unidentified artists began a campaign of illumination, painting more than forty-three full-page miniatures, and augmenting several key text pages with naturalistic flowers and insects. Working in gouache, an opaque watercolor, the artists signed a number of their paintings with the monograms “AV” or “NG.” Where signatures appear, so do dates, and their range from 1613 to 1616 indicates that the project extended over three to four years. The book underwent a complete transformation beginning with the removal of its printed title page, replaced with a handwritten one with penwork in brilliant red, orange, blue, and gold. Uprooted flowers, perhaps subtly suggestive of Zader’s recent death, bloom beneath his name, and beetles crawl among the inscribed publication information. An abundance of delicately rendered blossoms seems to sprout out of the paper margins throughout the opening pages, as if the book itself was a fertile, life-giving ground. Yet among the cheerful buds lurk warnings about the fleeting quality of life: a fly is ensnared in a spider’s web on one page, while on another a child blows bubbles over his deceased counterpart in an image of Vanitas inscribed ominously Hodie mihi cras tibi (today it is I, tomorrow, you) (fig. 2).

Emblem of Vanitas, with floral borders. From Jakob Zader, Die schöne Sommerzeit, acc. no. W.937, fols. 3v–A2r

Even from these first illuminations, it is clear that the artists were drawing upon a number of earlier and contemporary traditions. The book’s small scale, measuring just under 6 by 3 1/2 inches, is in keeping with the average size of medieval private devotional manuscripts such as books of hours. Those earlier books clearly provided inspirations for elements such as the floral borders, a fashion that reached its peak in the fifteenth century, and which is well represented in the Walters collection.[5] The image of Vanitas, however, may have been inspired by a similar emblem printed by Gabriel Rollenhagen in 1613, the same year the paintings in this book were begun.[6] The rest of the images play off the allegorical concepts put forth by Zader, and present a remarkably rich variety of subjects that capture both the physical and spiritual world of the early seventeenth century.

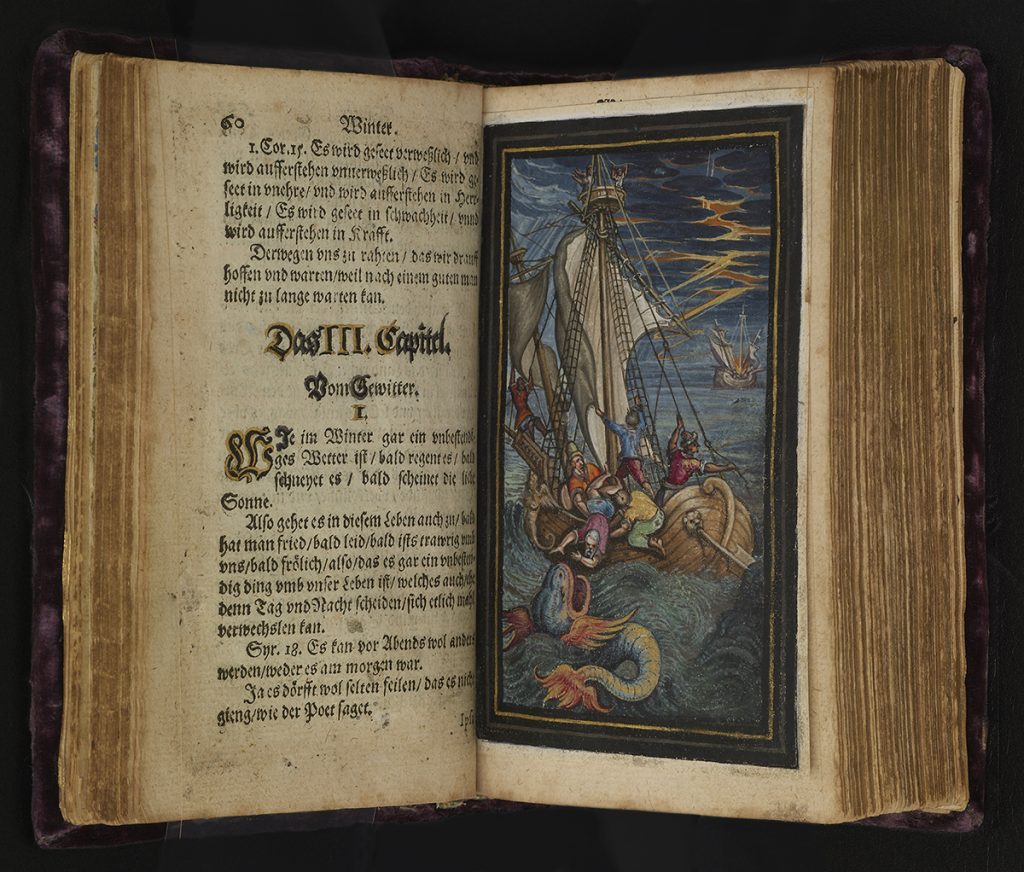

Shipwreck/Jonah and the Whale. From Jakob Zader, Die schöne Sommerzeit, acc. no. W.937, no. 7r

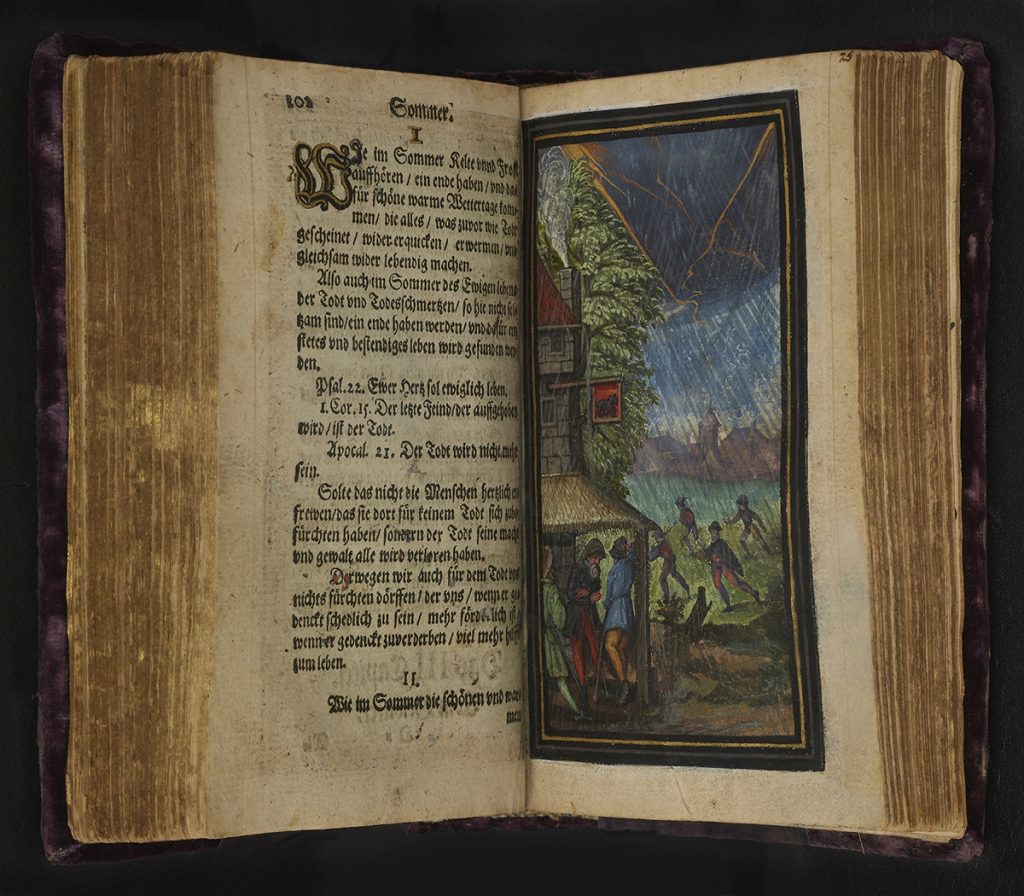

Given the text’s spiritual themes, it is surprising that there are very few overtly religious images. Instead, the reader is provided with worldly scenes that are meant to be studied, interpreted, and decoded. For instance, a shipwreck on a churning sea recalls the trials of Jonah (fig. 3), while a hen sheltering chicks from the myriad dangers around them represents Christ taking followers under his wing and shielding them from evil. While this latter concept could be conveyed in any number of settings, here the hen is huddled down during an evening snowfall, a subtle detail that demonstrates how the dichotomy between winter and summer, as defined by Zader in his allegory, often drives the imagery. Creating visual images to illustrate this unusual text led the artists to make delightfully unexpected choices, and it is in these non-traditional images that their talent is most apparent. While painting gardens in full bloom would likely have been part of a professional artist’s repertoire, rendering a frozen formal garden in a way that is still elegant and enchanting would have been a formidable challenge. So, too, would the artist need to possess natural skill and strong powers of observation to convincingly portray people running through sheets of rain to take shelter from a sudden spring thunderstorm (fig. 4).

Taking Shelter from a Thunderstorm. From Jakob Zader, Die schöne Sommerzeit, acc. no. W.937, no. 25

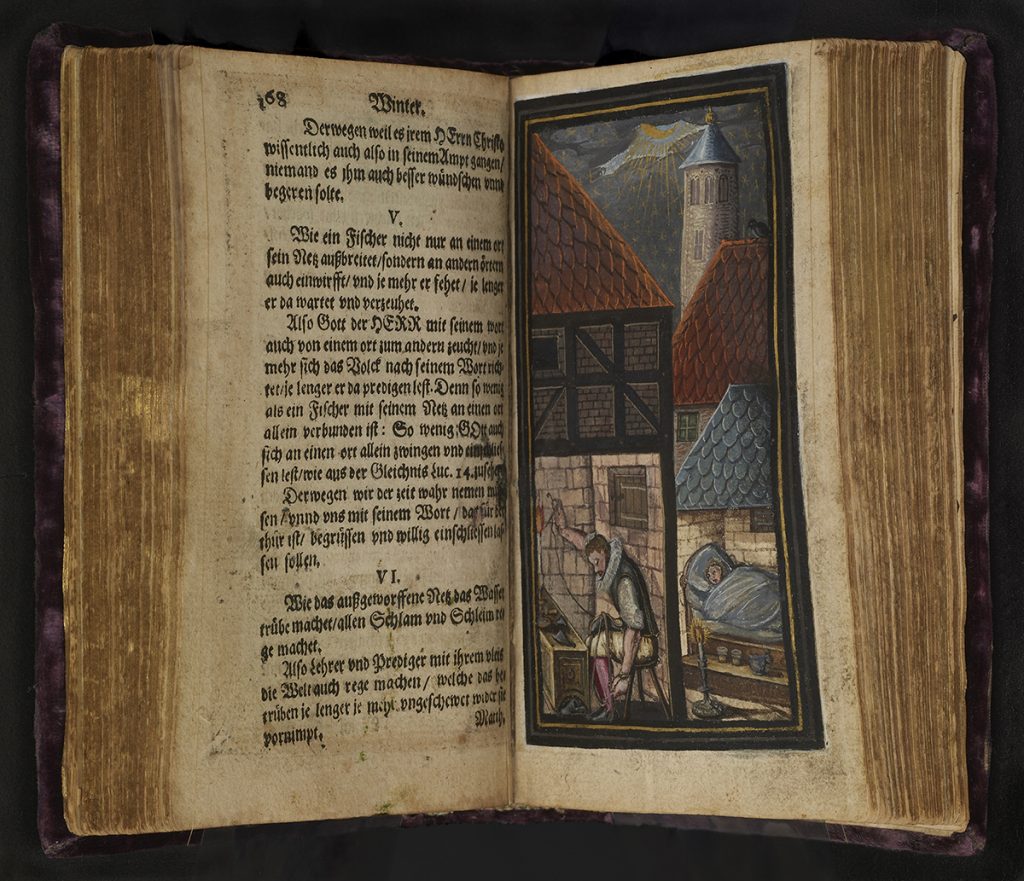

While these unusual images evoke a sense of captured moments from everyday life, others, such as depictions of workers and artisans, are heavily steeped in specific visual traditions. Scenes of shepherds tending their flocks and farmers sowing seeds and gathering the harvest are no doubt drawn from the labors of the months often found in medieval calendars.[7] German trade books, which documented the skills and working methods of local guild members in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, likewise provided an iconographic baseline from which to work for depictions of trades.[8] Even when looking to earlier sources, however, the artists tethered the way they rendered themes to their own moment, and in doing so provided us with a fascinating visual record of their contemporaries’ dress, work habits and techniques, landscapes and cityscapes, and even glimpses of their quiet, private moments. In all of their images, the artists pushed beyond simple illustration, creating instead individual masterpieces full of remarkable detail and imbued with both spatial and emotional depth. They did not simply depict a potter at his wheel, but also his colleagues mining the clay and finishing the pots in a fiery kiln in the distance; the cobbler sews his shoes, but he does so by candlelight under a shingled roof bathed in moonlight, while a child attempts to sleep in the next room (fig. 5).

Cobbler Working at Night. From Jakob Zader, Die schöne Sommerzeit, acc. no. W.937, no. 21

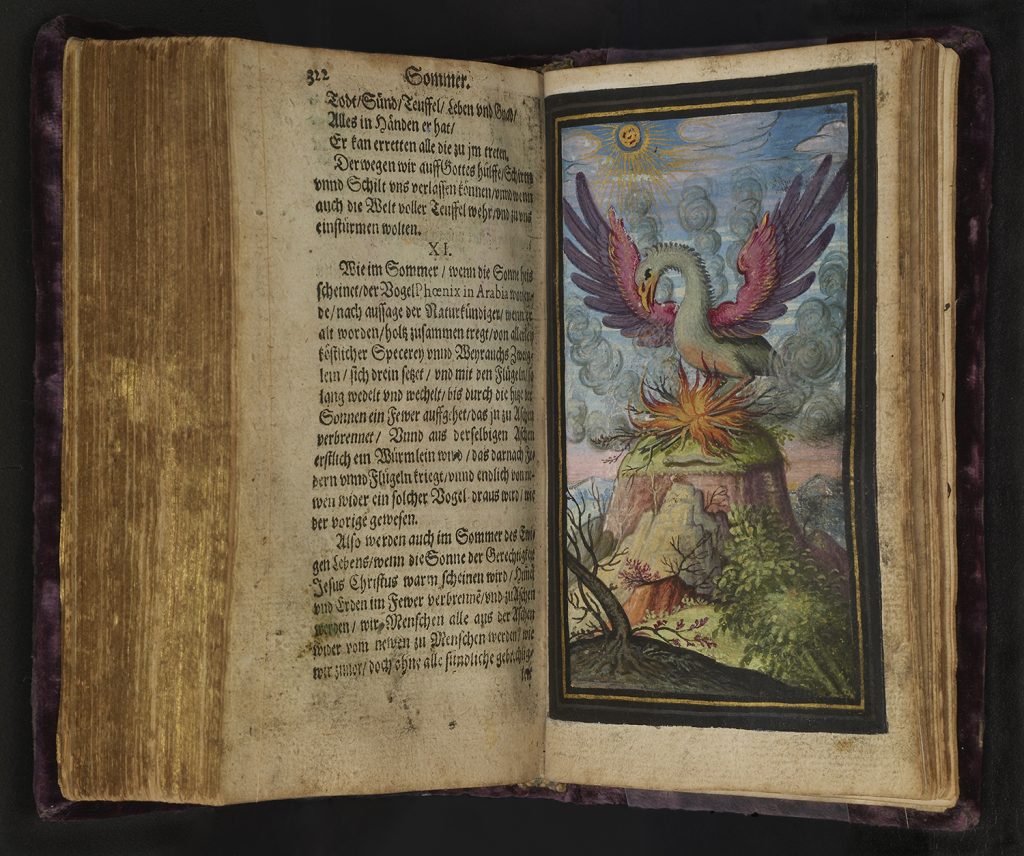

Although the contemporary dress and humanity of these scenes gives them an immediacy to which the book’s users would certainly have responded, the timeless truths found in the natural world are given an equally important role to play. The book’s artists astutely incorporated animals and insects imbued with moralizing and symbolic meanings that would have been familiar by this period. Their sources for these images were medieval bestiaries, heavily illustrated manuscripts that blended scientific knowledge with moral lessons associated with each beast they documented.[9] Zader’s book is therefore also a menagerie, teeming with creatures like the phoenix, lions, bears, bees, stags, kingfishers, pelicans, and eagles. They each carry with them layers of meaning, whether it is the unmistakable resurrection symbolism of the phoenix rising from the ash and flames (fig. 6), or the more subtle image of a stag, which renews itself by shedding its old antlers just as mankind sheds their sins. This way of understanding the beasts of this world as spiritual and moral guides was absolutely key in the medieval mindset and beyond, and the lack of a bestiary has long been recognized as a lacuna in the Walters’ manuscript collection. Through the addition of this imagery, the Zader book therefore helps close a significant gap in the Walters’ holdings.

Phoenix. From Jakob Zader, Die schöne Sommerzeit, 1603, acc. no. W.937, no. 39

Taken together, the rich variety and skillful artistry of the book’s illumination program makes it truly unique, not just within the Walters collection, but more broadly as a work of art. No other known Lutheran treatise received illumination like this one: it is an anomaly, a singular example of artistic patronage of a kind unheard of in Lutheran book art of this period. This was undoubtedly a special commission, one that transformed a printed text into an intensely visual devotional tool. Many questions remain, and tantalizing clues scattered throughout the book may, in time, help answer them. The issue of patronage is an important one, especially given what a rare, and potentially problematic, project this was for a Lutheran to commission at a time when believers were turning away from the decadence of Catholicism. It may, in fact, be possible to rediscover the people behind the book’s production, for a portrait of the patrons—a couple and their four children—can be found at the foot of the Crucifixion image, and scattered inscriptions written in silver may provide clues to their identity. The specific and prominent inclusion of the city of Halle, as seen in fig. 1, is suggestive of their place of residence. As a small but heavily Lutheran community close to Wittenberg, the city may preserve records of a wealthy family of this size living in Halle at that moment.

The artists that the family commissioned may also be discoverable by triangulating their initials with the dates of production and their distinctive visual style. Such thick, painterly applications of gouache were not typical of book artists in Germany during this period, who generally tended toward ink drawings and light washes of color. This difference in working method, combined with the fact that manuscript illumination was a dying art by the seventeenth century, suggests that they may have been trained as panel painters. They tackled an unconventional project in their own way, and the novelty of their work is genuinely thrilling. Their work in this book in fact presents us with a rare opportunity, for we are looking at the first—and only—time this text was illustrated. Other copies of Zader’s publications are devoid of all imagery, and no other known work contains the group of images found in this book. It appears, then, that the artists were making decisions as they went regarding what to show, and how to show it. In manuscript illumination, scholars are often working with copies, and with iconography that was established in some distant, now lost, work, so the first breath of invention can be elusive. Studying these artists’ approach to creating text and image relationships in the Zader book could teach us much, and may help inform how we understand book illuminators’ working methods and creativity on a broader scale.

The captivating images created for Zader’s treatise transformed the book into a contemplative tool for its users, and offer us today an unprecedented witness to personal faith, and a rare insight into how Lutherans visualized theological thought a century after Martin Luther. Having remained in private hands for the past century, this extraordinary book has never before been available for study or publication. Its addition to the Walters collection is in keeping with the spirit and philosophy of Henry Walters himself, who felt an obligation to acquire, preserve, and share books of exceptional rarity and singular cultural significance. This is one such book.

Lynley Anne Herbert ([email protected]) is the Robert and Nancy Hall Associate Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the Walters Art Museum.

Dedicated to Yu Na Han, Walters Zanvyl-Krieger Fellow at the Walters Art Museum from 2015 to 2017, whose knowledge of Lutheran art was invaluable for recognizing the importance of this book.

[1]The city was identified as Halle by the dealer, Jörn Günther Rare Books, Stalden and Basel.

[2]Jakob Zader, Die schöne Sommerzeit des ewigen Lebens, so nach dem trüben Winter vdieser Welt angehen wird (Wittenberg: Georg Müller for Paul Helwig, 1603). The book, which measures 5 7/8 by 3 1/2 inches (14.8 × 9 cm), contained 352 paper pages at the time of publication, with eight additional contemporary pages inscribed with religious chants added in the back. This copy was owned by Finnish art collector and dealer Gösta Stenman in the early 1900s, and had been passed down through his family until the present. Purchased from Jörn Günther Rare Books, Switzerland, whose initial research and book description has provided a crucial jumping-off point. See Jörn Günther, In Pursuit of Masterpieces: A Selection of Illuminated Manuscripts and Early Printed Books (Stalden, 2016), no. 64, and also the more thorough dealer description (unpublished), titled “German Country Life of the Early Seventeenth Century—Unique Copy of a German Edifying Book.”

[3] The only other recorded copy of Zader’s 1603 edition is in the collection of the National Library of Sweden, Stockholm, inv. no. 10417659. For information about Jakob Zader’s life and accomplishments, see the sermon by E. Lauterbach, Christliche Prediger gebür … beyehrlicher Begrebnus des … Herrn M. Jacobi Zaderi (Wittenberg, 1614).

[4] Much new scholarship has been generated around the Reformation recently with the celebration of its five hundredth anniversary in 2017. For recent discussions of Lutheran attitudes about art, see Bridget Heal and Joseph Leo Koerner, eds., Art and Religious Reform in Early Modern Europe (Hoboken, N.J., 2017).

[5] Although most commonly seen in French and Flemish manuscripts, these illusionistic flowers can also be found in German and Spanish manuscripts of the period. A few examples from the Walters collection include a missal attributed to the Masters of the Dark Eyes, late 15th–early 16th century, W.175, fols. 90v–91r; the Almugavar Hours, 1510–20, W.420, fols. 57v–58r; a book of hours for the use of Rome, ca. 1490–1500, W.431, fols. 77v–78r; and the Aussem Hours, early 16th century, W.437, fols. 19v–20r. The way in which the flowers seem to sprout out of the pages is also reminiscent of the Mira calligraphiae monumenta, illustrated by Joris Hoefnagel in the late sixteenth century. See J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 20, fol. 11.

[6] Günther, In Pursuit of Masterpieces, no. 64. See Gabriel Rollenhagen, Selectorum emblematum centuria secunda (Utrecht: Ex officina Crispiani Passaei : Prostant apud Joan. Janssoniu[m] bibli. Arnh, 1613), pl. 50.

[7] An example of shepherds can be found in a book of hours composed in Bruges or Ghent, ca. 1500, W.427, fols. 5v–6r, while similar farmers appear in a Flemish psalter, ca. 1270–80, W.35, fols. 4v–5r, and in a Flemish book of hours, ca. 1500, W.428, fols. 10v–11r.

[8] For an important collection of these, see especially the Mendel II group from “Die Hausbücher der Nürnberger Zwölfbrüderstiftungen: Digitale Erschließung und Edition von Handwerkerdarstellungen des 15.–19. Jahrhunderts.”

[9] A wonderful example of a thirteenth-century bestiary is Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Bodl. 764.